Course

Acute Pneumothorax

Course Highlights

- In this Acute Pneumothorax course, we will learn about the different types of pneumothoraces.

- You’ll also learn the signs and symptoms of pneumothorax.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of the treatment approaches for pneumothorax.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 1

Course By:

Nonnie Breytspraak, MSN, RN, CEN, TCRN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

As a healthcare professional, your role in recognizing and treating pneumothorax is crucial. Patients with pneumothorax may present in varying degrees of distress depending on the type and size of their pneumothorax. It is essential to recognize the possible signs and symptoms, know what assessment findings to look for, anticipate the diagnostic tests and treatments, and be familiar with your role in monitoring the patient for complications. Your vigilance and knowledge can make a significant difference in patient outcomes.

Definition

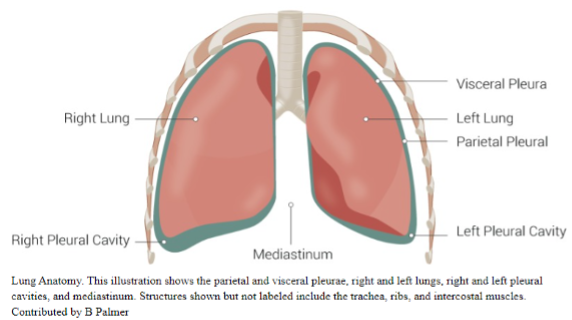

Pneumothorax is an abnormal collection of gas or air outside the lung between the visceral and parietal pleura, known as the pleural space. The air may come from the rupture of the visceral pleura, the parietal pleura, or both. (5, 6, 15, 17)

There are three primary types of pneumothoraces: spontaneous, traumatic, and iatrogenic pneumothorax.

- Spontaneous Pneumothorax – occurs without traumatic injury and can be further categorized as:

-

- Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax (PSP) – occurs with no underlying pulmonary disease

-

- Secondary Spontaneous Pneumothorax (SSP) – occurs in patients with underlying pulmonary disease

- Traumatic Pneumothorax – occurs as a result of a traumatic injury such as:

-

- Blunt traumatic injury

-

- Penetrating traumatic injury

- Iatrogenic Pneumothorax – occurs as a complication of medical intervention or treatment (5, 6, 15, 18)

Some sources categorize iatrogenic pneumothorax as a subset of traumatic pneumothorax. Some literature recognizes the following as pneumothorax types:

- Tension pneumothorax – occurs when a pneumothorax grows large enough to exert pressure on the mediastinum, the contralateral lung, and the vena cava, preventing blood from returning to the heart. It is fatal without immediate intervention. Tension pneumothorax is a complication of a spontaneous, traumatic, or iatrogenic pneumothorax. (6, 8)

- Pneumomediastinum – occurs when alveoli ruptures into the mediastinal space. The pressure from the air in the mediastinum may rise quickly and rupture the parietal pleura, leading to pneumothorax. Pneumomediastinum is a potential cause of pneumothorax. (6)

- Catamenial pneumothorax – occurs in women between the ages of 30 and 50. It is often called thoracic endometriosis because it typically occurs one to three days after the onset of menses. Catamenial pneumothorax is a type of spontaneous pneumothorax. (6, 12)

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Where does air accumulate in a pneumothorax?

- What are the three primary types of pneumothoraces?

- What category may an iatrogenic be classified under?

- What life-threatening condition can spontaneous, traumatic, or iatrogenic pneumothorax progress to?

Pathophysiology

Regardless of the cause of the pneumothorax, the basic pathophysiology involves a pressure gradient change in the thorax. (5, 6) The pleural space is relatively negative or lower than atmospheric pressure.

During normal respiration, surface tension between the parietal and visceral pleurae causes the lungs to expand with chest expansion, and then the lungs naturally recoil due to their elastic nature. When air enters the pleural space, the pressure gradient changes, and the lung will continue to get smaller or collapse until the pressure gradient equalizes or the source of the air leak is sealed. (5, 6)

As the pneumothorax gets larger, the patient will suffer a decrease in vital capacity and partial pressure of oxygen. (6) If the pneumothorax grows large enough, it may progress to a life-threatening tension pneumothorax (3). In a tension pneumothorax, the pressure is significant enough to compress the heart and vena cava, reducing blood return to the heart and deteriorating the patient’s cardiopulmonary status. (3, 5, 6, 15) The pressure may also be substantial enough to compress the trachea, deviating away from the tension pneumothorax. If left untreated, a tension pneumothorax will result in fatal cardiopulmonary collapse (18).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Is the pleural space pressure higher or lower than atmospheric pressure?

- What causes the lungs to expand in normal respiration?

- What causes the lungs to recoil in normal respiration?

- What happens to the lung when air enters the pleural space?

- What is the result of untreated tension pneumothorax?

Etiology and Epidemiology

The etiology and epidemiology of pneumothorax depend on the type of pneumothorax.

Spontaneous Pneumothorax

Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax (PSP)

As we defined earlier, PSP arises without a traumatic event or any known underlying lung disease. (12, 18) It typically occurs in patients aged 20 to 30 and is three to six times more likely in men. (6, 12, 15) Estimates of occurrence are 1 to 1.2 per 100,000 persons per year in women and 7 to 7.4 per 100,000 in men. (5, 6, 12, 15)

The typical clinical picture for a PSP patient is a young, tall, thin male who smokes. Smoking cigarettes and cannabis increases the relative risk for PSP in women by 4, 14, and 68 times for light, moderate, and heavy smokers, respectively. (12) In men, the relative risk is 7, 21, and 102 times higher for light, moderate, and heavy smokers, respectively. (12)

PSP is caused by subpleural blebs and bullae, which are cystic, air-filled spaces that can form between the lung and the pleura. (7, 12, 15) Blebs are usually 1cm or less in diameter, and bullae can be larger than 1 cm. (7) When they rupture into the pleural cavity, they cause pneumothorax.

It is unclear why blebs and bullae form, but it is theorized that they may be from increasing negative pressure or increased alveolar stretch at the apex of the lung during growth, which would explain why the typical PSP patient is tall. (12) One study of patients with pectus excavatum (PE) found that bleb formation was noted in 26.5% of cases, and nearly 6% of PE patients, who are also commonly tall and thin, also developed PSP. (9)

Secondary Spontaneous Pneumothorax (SSP)

SSP is a pneumothorax that develops as a complication of an underlying lung disease, which is usually already diagnosed before presentation with SSP. (12, 18) It typically occurs in patients aged 60 and older and is three times more likely in men. Estimates of occurrence are 2 per 100,000 persons per year in women and 6.3 per 100,000 persons per year in men. (6, 15) Smoking increases SSP risk greater than 20-fold in men and almost 10-fold in women. (6)

There are numerous underlying conditions and diseases associated with SSP, including:

- Asthma

- Bacterial pneumonia

- Bronchogenic carcinoma or metastatic malignancy

- COPD

- COVID-19 pneumonia

- HIV/AIDS with pneumocystis pneumonitis (PCP) infection

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Inhaled and intravenous drug use (marijuana, cocaine)

- Interstitial lung disease

- Necrotizing pneumonia

- Sarcoidosis

- Thoracic endometriosis (catamenial pneumothorax)

- Tuberculosis

(1, 6, 12, 15)

COPD is the most common cause of SSP, with an incidence of 26 pneumothoraces per 100,000 patients and 50 to 70 percent of SSP cases caused by COPD in one study. (6, 12, 15) In COPD and sarcoidosis, rupture of blebs and bullae into the pleural space is usually the cause of SSP, but air trapping may also contribute to pneumothorax. (12)

Lung malignancy and necrotizing pneumonia may form necrotic cysts that rupture into the pleural space, causing SSP. (12) Tuberculosis can lead to pneumothorax when a tuberculous cavity ruptures into the pleural space. (12) Bacterial lung infections may invade the pleural space, causing empyema and creating hydropneumothorax, an accumulation of air and fluid. (12)

Traumatic Pneumothorax

Trauma is the leading cause of pneumothorax. (6, 8) Pneumothorax occurs in 40 to 50 percent blunt trauma to the chest and over 80 percent penetrating trauma to the chest. (2, 12, 14, 22)

In blunt trauma, the most likely causes of pneumothorax are rib fracture, sternal fracture, and sternoclavicular fracture. (8, 14) In penetrating trauma, gunshot wounds and stab wounds are the most common causes of pneumothorax. (22)

Iatrogenic Pneumothorax

Iatrogenic pneumothorax is becoming increasingly common with the rapid advances in medical care and increasing dependence on invasive monitoring and procedures. (6, 12, 15) The incidence of iatrogenic pneumothorax is five to seven per 10,000 hospital admissions in the United States. (6, 15)

A study of 12,000 procedures found iatrogenic pneumothorax in 1.4 percent and 57 percent were a result of emergency procedures. (12) Teaching hospitals were found to have a higher incidence of iatrogenic pneumothorax than nonteaching hospitals. (12)

Potential causes of iatrogenic pneumothorax include:

- Central venous catheter placement

- Intercostal nerve block

- Pacemaker placement

- Pleural biopsy

- Positive pressure ventilation

- Thoracentesis

- Tracheostomy

- Transbronchial lung biopsy

- Transthoracic pulmonary nodule biopsy

(12, 15)

The most common procedures leading to iatrogenic pneumothorax are central venous catheter placement (44%), thoracentesis (20%), and barotrauma from mechanical ventilation (9%). (12)

Other Pneumothorax

Some cases of pneumothorax have been associated with anorexia nervosa, exercise, illicit drug use, immunosuppressant drugs, air travel, and scuba diving. (12, 16)

- Anorexia nervosa

- It is theorized that severe malnutrition may play a role in pulmonary abnormalities leading to pneumothorax in this population

- Exercise, illicit drug use, immunosuppressant drugs

- There are theories that deeper inhalation and Valsalva maneuvers may contribute to the development of pneumothorax

- Air travel and scuba diving

- The change in atmospheric pressure may contribute to the development of pneumothorax

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Are PSP and SSP more common in men or women?

- What is the typical profile of a patient with a PSP?

- What is the most common cause of SSP?

- What is the leading cause of pneumothorax?

- What is the most common cause of iatrogenic pneumothorax?

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

The clinical signs and symptoms and their intensity will depend on the size of the pneumothorax and its impact on the patient’s cardiopulmonary function. (6, 10) The most common presenting symptoms reported are chest pain at 64 percent and shortness of breath at 85 percent. (10, 18) These symptoms usually come on suddenly when the patient is at rest. (10, 15)

Chest pain is usually described as sharp and stabbing and often radiates to the ipsilateral arm or shoulder. (18) The patient may also present with:

- Asymmetrical lung expansion

- Diminished breath sounds

- Decreased tactile fremitus

- Hyperresonant percussion

- Increased respiratory rate

- Pleuritic chest pain (discomfort with breathing)

(6, 10, 15, 18)

Ominous signs of a life-threatening tension pneumothorax include:

- Absent breath sounds on the affected side

- Anxiety

- Cyanosis

- Hypotension

- Jugular venous distension

- Respiratory distress

- Tachycardia greater than 134 BPM

- Tracheal deviation

(3, 6, 10, 15, 18)

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are the most common presenting symptoms of pneumothorax?

- How is chest pain with pneumothorax described?

- What are three of the signs of tension pneumothorax?

Assessment

The first step in assessing a patient for possible pneumothorax is to take a thorough history, with close attention to:

- History of pneumothorax – recurrence is seen in 15 to 40 percent of cases

- Family history of pneumothorax – potential genetic causes

- Medical history – looking for any underlying lung disease

- Recent medical treatment – looking for any iatrogenic causes of pneumothorax

- Recent trauma to the chest

- Smoking history

(6, 10, 15)

The next step is to perform a thorough exam of the patient. This includes a complete set of vital signs and a physical assessment of their cardiopulmonary system, looking for any clinical signs and symptoms mentioned earlier. (10, 15)

Diagnostics

Imaging is used to detect pneumothorax.

Chest Radiography (CXR)

CXR is the most common diagnostic tool for pneumothorax, but it has limitations (6, 10). The patient’s position will determine the size of the pneumothorax that may be seen on CXR. (10)

- Upright position – as little as 50 mL of air in the pleural space may be detected

- Supine position – at least 500 mL of air must be present for detection (10)

Ultrasonography (US)

The US is the method of choice for an unstable patient or a trauma patient. (6, 10) An extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma (E-FAST) has shown high sensitivity and specificity for pneumothorax; however, the results depend on user experience, according to recent studies. (6, 10) There is also a risk for a false positive E-FAST if underlying lung disease is present. (10)

Computed Tomography (CT)

Chest CT is the most accurate imaging modality compared to CXR and US. (6, 10) It is not recommended as the first choice because of the higher radiation levels. However, it may be necessary if the US and CXR are negative and there is still a high index of suspicion for pneumothorax. (6, 8) Chest CT may detect small, occult pneumothoraces in trauma patients not detected on CXR. (8,10, 14, 22) If pneumothorax is suspected and the patient requires mechanical ventilation, Chest CT is recommended to determine if chest thoracostomy is needed to prevent barotrauma and worsening pneumothorax. (14, 22)

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Which CXR position detects as little as 50 mL of air in the pleural space?

- Which imaging tool is recommended for an unstable or trauma patient?

- Which imaging tool is most accurate in detecting pneumothorax?

- Which imaging tool is most likely to have a false positive if underlying lung disease is present?

Treatment

The goals of pneumothorax treatment are to:

- Manage symptoms if the patient is symptomatic

- Restore lung volume and air-free pleural space

- Prevent recurrences

(6)

Treatment guidelines used to be built around the size of the pneumothorax, but there is little consensus on the size cutoff for treatment.

For example:

- The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) defines a small pneumothorax as <3 cm between the chest wall and the pleural line at the apex of the lung on a CXR, and a large pneumothorax is ≥3cm.

- The British Thoracic Society guidelines define a small pneumothorax as <2 cm and a large pneumothorax as ≥2 cm.

- The Light Index defines a small pneumothorax as 15% or less of the thoracic volume or approximately 1.25 cm.

(6, 10, 13, 17, 19)

More recent research has led treatment guidelines to rely less on the size of the pneumothorax and more on the patient’s clinical presentation and risk stratification for complications or recurrence. (6, 11, 13, 19)

Let’s review the treatment approaches for the management of pneumothorax.

Observation without Supplemental Oxygen

Asymptomatic or stable patients with pneumothorax may be treated with observation and without supplemental oxygen. (18, 21) Pneumothorax can be reabsorbed on room air at a rate of 1.25 to 1.5 percent daily. (6, 15)

The ACCP defines stable as meeting all the following criteria:

- Able to speak in complete sentences

- Blood pressure within defined limits

- Heart rate between 60 and 120 beats per minute

- Oxygen saturation rate greater than 90 percent on room air

- Respiratory rate less than 24 breaths per minute

(13)

The ACCP recommends that stable and asymptomatic patients be observed in the emergency department (ED) for six hours after diagnosing pneumothorax for a follow-up CXR. (6, 13)

If the follow-up CXR does not show any enlargement of pneumothorax, the patient may be discharged with instructions to follow up in two days for repeat imaging and again in one month to repeat imaging and verify the lung has re-expanded. (6, 13, 21)

The patient should be given clear guidance to return to the ED if symptoms worsen.

Observation with Supplemental Oxygen

If the patient is stable, but the six-hour follow-up CXR shows any increase in pneumothorax or has underlying lung disease, they may be admitted for observation with supplemental oxygen. (6, 13, 15, 18)

Administering supplemental oxygen at 3 liters per minute increases the rate of pleural air absorption fourfold. (6) It is important to note that a high-flow nasal cannula should not be used because a small amount of positive pressure is delivered, which could worsen pneumothorax. (13) Follow-up imaging should continue and will guide any further interventions. (6, 13)

Thoracentesis and One-Way Valve Insertion

Needle aspiration of pneumothorax, or thoracentesis, may be indicated if the patient has severe dyspnea or other intolerable symptoms. (6, 13, 18, 19) Once the air is removed, it is recommended that the stopcock be closed, and the catheter be taped to the chest wall until a follow-up CXR can be completed to evaluate lung expansion. (13)

If the lung is fully expanded and symptoms have resolved, the catheter may be removed, and the patient may be discharged with instructions for follow-up imaging and exam in one to two days. (13, 19)

If the lung has not fully expanded, pneumothorax has worsened, or symptoms have not resolved, the patient will need a chest catheter or chest tube thoracostomy. (13) (See Chest Catheter or Chest Tube Placement section below.)

If the lung has not fully expanded, but pneumothorax has not worsened, and symptoms have resolved, the patient may have a portable one-way valve attached to the catheter and be discharged with instructions to follow up in one to two days. (6, 13, 19) A Heimlich valve is a one-way flutter valve left open to air to evacuate pneumothorax. (6, 19)

Chest Catheter or Chest Tube Placement

Patients who have failed more conservative management or are symptomatic require a chest catheter thoracostomy or chest tube thoracostomy. (6, 13, 14, 15, 18, 19, 22)

A chest catheter is generally 8 French to 14 French, and a chest tube is 22 French or larger. (13) Pneumothorax can be successfully evacuated with a smaller chest catheter, but a larger bore chest tube is necessary if there is a concomitant hemothorax that needs to be evacuated. (6, 13, 19)

Pneumothorax resolves in 70 percent of patients within 72 hours when the chest tube is connected to a water seal. (13) However, some providers may order the chest tube to be connected to wall suction, usually at -10 to -20 cm H2O, to promote faster lung expansion. (13) Some providers may also order the chest tube to be clamped for four to 12 hours before removal with a follow-up CXR to evaluate for any re-accumulation of air. (13) Wall suction and chest tube clamping are not without risk.

Please see the Safety Considerations section below.

Needle Decompression and Finger Thoracostomy

Patients demonstrating signs of tension pneumothorax require immediate needle decompression or finger thoracostomy followed by chest tube thoracostomy to prevent cardiopulmonary collapse. (6, 13, 14, 15, 18, 19, 22)

Surgery

Surgical intervention may be necessary in the following circumstances:

- Bilateral pneumothorax

- Contralateral pneumothorax

- High risk of recurrent pneumothorax for patients who live at high altitudes or want to continue to travel

- Patients with AIDS

- Persistent air leak for longer than five to seven days

- Pneumothorax in a patient in a high-risk occupation, such as a diver or pilot

- Repeated pneumothorax

- Traumatic open pneumothorax requiring surgical repair (6, 13, 16, 19, 20)

Patients who are stable for surgery may undergo video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) for bleb resection, lung resection, or pleurodesis. (6, 13) Patients who are not stable enough for surgery may have pleurodesis via tube thoracostomy. (6, 13)

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are the treatment goals for pneumothorax?

- What is the likely treatment approach for an asymptomatic patient with a small pneumothorax found incidentally on imaging?

- What is the treatment approach for a patient with signs of tension pneumothorax?

- What is the treatment approach for a patient who has failed conservative management?

- What is the treatment approach for a persistent air leak lasting longer than five to seven days?

Pharmacology

Pneumothorax and invasive interventions can be painful. Invasive interventions such as thoracentesis and thoracostomy place the patient at risk for infection. If the patient is relatively stable and there is time, a local anesthetic such as lidocaine should be used before invasive procedures. (6, 13, 14, 18, 22)

Opiate analgesics should be made available to promote pain relief and pulmonary toilet. (6, 13, 14, 18, 22) Prophylactic antibiotics are recommended if invasive interventions are performed to prevent any infection. (6, 13, 14, 18, 22)

Safety Considerations

When caring for a pneumothorax patient, there are many potential complications that you must monitor vigilantly. The two most concerning are:

- Tension pneumothorax – know the signs and be prepared to intervene immediately.

- Re-expansion pulmonary edema – may occur on the ipsilateral or contralateral side as the lung expands.

Managing a chest tube and drainage system should only be done by healthcare staff who have demonstrated competency. (6) If the chest tube is ordered to be clamped before removal, it is imperative to monitor very closely for tension pneumothorax, and the assigned healthcare staff should know to immediately unclamp the tubing, notify the provider, and support the patient if a tension pneumothorax develops. (6, 13)

Research Findings

Some researchers take issue with the premise that PSP arises with no underlying lung disease. (7, 12) Blebs and bullae are also known as emphysema-like change (ELC), and examination of resected blebs and bullae reveals cellular inflammation. (7) Research has shown chronic distal airway inflammation and evidence of respiratory bronchiolitis in 88.6% of patients undergoing surgery for PSP, leading some to believe there is an underlying lung disease in PSP. (7)

Other theories postulate that PSP may have a genetic cause. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome, homocystinuria, and Birt-Hogg-Dube (BHD) syndrome are all inherited conditions that have all been linked to PSP. (4, 6, 12) In some cases, pneumothorax may be the first indication of such genetic conditions. (4)

Trends in Conservative Pneumothorax Management

Thoracentesis and one-way valves are often used first for patients resistant to hospitalization, but their success rates are mixed. One study showed successful results in up to 87 percent of thoracentesis cases, but another study showed a 40 percent failure rate, and at least 50 percent of thoracentesis cases still needed hospitalization. (6, 19)

One-way valve studies show that many patients still require hospitalization, but their length of stay and re-hospitalization rates were lower compared with chest tube thoracostomy patients. (6, 19) Patients report less pain with the smaller catheter and valve, but the length of time to fully expand the lung and remove the valve is significantly longer than with a chest tube thoracostomy. (6, 19)

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Where does air accumulate in a pneumothorax?

- What are the three primary types of pneumothoraces?

- What category may an iatrogenic be classified under?

- What life-threatening condition can spontaneous, traumatic, or iatrogenic pneumothorax progress to?

- Is the pleural space pressure higher or lower than atmospheric pressure?

- What causes the lungs to expand in normal respiration?

- What causes the lungs to recoil in normal respiration?

- What happens to the lung when air enters the pleural space?

- What is the result of untreated tension pneumothorax?

- Are PSP and SSP more common in men or women?

- What is the typical profile of a patient with a PSP?

- What is the most common cause of SSP?

- What is the leading cause of pneumothorax?

- What is the most common cause of iatrogenic pneumothorax?

- What are the most common presenting symptoms of pneumothorax?

- How is chest pain with pneumothorax described?

- What are three of the signs of tension pneumothorax?

- Which CXR position detects as little as 50 mL of air in the pleural space?

- Which imaging tool is recommended for an unstable or trauma patient?

- Which imaging tool is most accurate in detecting pneumothorax?

- Which imaging tool is most likely to have a false positive if underlying lung disease is present?

- What are the treatment goals for pneumothorax?

- What is the likely treatment approach for an asymptomatic patient with a small pneumothorax found incidentally on imaging?

- What is the treatment approach for a patient with signs of tension pneumothorax?

- What is the treatment approach for a patient who has failed conservative management?

- What is the treatment approach for a persistent air leak lasting longer than five to seven days?

Conclusion

Pneumothorax is a relatively common presentation, especially in trauma patients. Health professionals must recognize the signs and intervene appropriately.

References + Disclaimer

- Bellini, R., M.C. Salandini, Cuttin, S., Stefania Di Mauro, Paolo Scarpazza, & Cotsoglou, C. (2020). Spontaneous pneumothorax as unusual presenting symptom of COVID-19 pneumonia: surgical management and pathological findings. Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-020-01343-4

- Bettoni, G., S, G., M, A., Spb, C., D, F., M, C., L, B., S, C., & P, A. (2024). Successful Needle Aspiration of a Traumatic Pneumothorax: A Case Report and Literature Review. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania), 60(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60040548

- Bischin, A. M., Manning, H. L., & Feller-Kopman, D. (2022). Lung Story Short: Differing Physiology of Tension Pneumothorax in Spontaneously Breathing and Mechanically Ventilated Patients. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 19(10), 1760–1763. https://doi.org/10.1513/annalsats.202203-188cc

- Boone, P. M., Scott, R. M., Marciniak, S. J., Henske, E. P., & Raby, B. A. (2019). The Genetics of Pneumothorax. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 199(11), 1344–1357. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201807-1212CI

- Costumbrado, J., & Ghassemzadeh, S. (2020). Pneumothorax, Spontaneous. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459302/

- Daley, B. J. (2024, Jan 22). Pneumothorax: Practice Essentials, Background, Anatomy. Medscape.com. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/424547-overview

- Hallifax, R. (2022). Aetiology of Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(3), 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11030490

- Kim, C.-W., Park, I.-H., Youn, Y., & Byun, C.-S. (2023). Occult Pneumothorax in Blunt Thoracic Trauma: Clinical Characteristics and Results of Delayed Tube Thoracostomy in a Level 1 Trauma Center. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(13), 4333. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12134333

- Lee, J., Jin Yong Jeong, Jong Hui Suh, Chan Beom Park, Kim, D., & Soo Seog Park. (2023). Diverse clinical presentation of primary spontaneous pneumothorax in patients with pectus excavatum. Frontiers in Surgery, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2023.1245049

- Lee, YC Gary. (2023, Sept 20). Clinical presentation and diagnosis of pneumothorax. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-presentation-and- diagnosis-of-pneumothorax?search=Acute%20pnuemothorax&source=searchresult&selectedTitle=4%7E150&usage_type=default&display_rank=4

- Lee, YC Gary. (2023, Sept 26). Pneumothorax: definitive management and prevention of recurrence. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pneumothorax- definitive-management-and-prevention-recurrence?search=Acute%20pnuemothorax &source=search_ result&selectedTitle=10%7E150&usage_ type=default&display_rank=10

- Lee, YC Gary. (2023, Jun 28). Pneumothorax in adults: epidemiology and etiology. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pneumothorax-in-adults- epidemiology-and-etiology?search=Acute%20pnuemothorax& source=search_result& selectedTitle=6%7E150&usage_type=default&display_

rank=6 - Lee, YC Gary. (2024, March 07). Treatment of primary spontaneous pneumothorax in adults. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-primary-spontaneous-pneumothorax-in adults?search=Acute%20pnuemothorax&source =search_ result&selectedTitle=2%7E150&usage_type=default&display_rank=2

- Legome, E. (2004, March 01). Initial evaluation and management of blunt thoracic Trauma in adults. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/initial-evaluation-and-management-of-blunt-thoracic-trauma-in-adults? sectionName= Pneumothorax&search=pneumothorax&topicRef=6706&anchor=H23

&source=see_link#H23 - McKnight, C. L., & Burns, B. (2023). Pneumothorax. NIH.gov; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441885/

- Mohr, L.C. (2023, Feb 07). Pneumothorax and air travel. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pneumothorax-and-air-travel?search=Acute%20pnuemothorax&source=search_result&selectedTitle=11%7E150&usage_type=default&display_rank=11

- Pleural Disease | British Thoracic Society | Better lung health for all. (2003, July). Www.brit-Thoracic.org.uk. https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/guidelines/pleural-disease/

- Sajadi-Ernazarova, K. R., Martin, J., & Gupta, N. (2020). Acute Pneumothorax Evaluation and Treatment. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538316/

- Shorthose, M., Barton, E., & Walker, S. (2023). The contemporary management of spontaneous pneumothorax in adults. Breathe, 19(4), 230135–230135. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.0135-2023

- Tokuda, R., Okada, Y., Nagashima, F., Kobayashi, M., Ishii, W., & Iizuka, R. (2022). Open pneumothorax with extensive thoracic defects sustained in a fall: a case report. Surgical Case Reports, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-022-01555-x

- Williams, O. D., & Penn, M. (2020). Can patients with traumatic pneumothorax be managed without insertion of an intercostal drain? Trauma, 23(1), 146040862094626. https://doi.org/10.1177/1460408620946261

- Winkle, J.M. & Legome, E. (2024, Mar 12). Initial evaluation and management of penetrating thoracic trauma in adults. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/initial-evaluation-and-management-of-penetrating-thoracic-trauma-in-adults?search=Acute%20pnuemothorax&source =search_ result&selectedTitle=14%7E150&usage_type=default&display_rank=14

- [Image] StatPearls Publishing LLC (2024). Lung Anatomy. From: Anatomy, Thorax, Lungs. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Creative Commons: Image allowed to be distributed without permission if cited.

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate