Course

Aphasia after Stroke

Course Highlights

- In this Aphasia after Stroke course, we will learn about the mechanisms of language processing and the impact of stroke on these systems.

- You’ll also learn and differentiate between various types of aphasia.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of evidence-based therapeutic interventions tailored to the individual needs of patients with aphasia.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 2

Course By:

Abbie Schmitt, MSN-Ed, RN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

Speech and language are a major factor in the human experience and quality of life, both in social interaction and in personal intellect and enjoyment. When they are disturbed as a consequence of a stroke, the functional loss has a huge impact.

In a broad context, language provides the ability to reflect on objects, actions, and events and, therefore, the mirror of all higher mental activity. In a narrower context, language provides a way to communicate complaints and problems to the healthcare team. Consequently, any process that interferes with speech or the understanding of spoken words touches the very core of holistic patient care.

Aphasia is a common and often debilitating consequence of stroke, profoundly affecting a patient’s ability to communicate. This condition, which results from damage to the language centers in the brain, can lead to difficulties in speaking, expression, understanding, reading, and writing.

For nurses, understanding aphasia and its implications is crucial in providing holistic care to stroke survivors. Effective nursing interventions not only enhance the quality of life for these patients but also support their families during the challenging recovery process. This course explores the complexities of aphasia, explaining the types, impact, and evidence-based nursing strategies to optimize patient outcomes and foster a supportive rehabilitative environment.

Definitions

It is important to review definitions as we create a foundation for understanding aphasia following a stroke. For this course, we will use the term “stroke,” which refers to a cerebrovascular accident (CVA). CVA is the recognized terminology among the medical community.

- Aphasia: The disruption of language abilities caused by neurologic damage, with acute onset secondary to stroke being the most common etiology.

- Cerebrovascular accident (CVA): A stroke. This is essentially defined as the sudden death of brain cells due to lack of oxygen, caused by blockage of blood flow or rupture of an artery to the brain.

- Dysarthria: Slurred speech

- Hemorrhagic stroke: Occurs when a weakened vessel ruptures and bleeds into the brain.

- Ischemic stroke: Occurs when a blood vessel supplying blood to the brain is obstructed.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): A procedure that uses magnetism, radio waves, and a computer to create pictures of areas inside the body.

- Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA): a temporary blockage of blood supply within the brain (mini-stroke).

- Tissue Plasminogen Activator (tPA): An enzyme that helps dissolve clots.

There are two major types of strokes. The first and more common type is ischemic stroke. This type of stroke happens when blood flow through the artery that supplies oxygen-rich blood to the brain becomes blocked. This blockage can be due to thrombotic events within the brain’s vasculature or embolic events, where clots formed elsewhere in the body travel to the brain.

The second major type of stroke is called hemorrhagic stroke. A hemorrhagic stroke is characterized by an artery in the brain leaking or rupturing, resulting in blood flooding the brain tissue. This bleeding puts too much pressure on brain cells, which damages them. There are two subtypes of hemorrhagic stroke: 1) intracerebral hemorrhage, which occurs when an artery in the brain bursts, flooding the surrounding tissue with blood and 2) subarachnoid hemorrhage, which occurs between the brain and the thin tissues that cover it.

In addition to the two major types of strokes, there is another type called a transient ischemic attack (TIA) also known as a mini-stroke. In TIAs, the blood supply to the brain is compromised for only a short time—usually no more than 5 minutes, which limits the damage to the brain.

Although speech and language are closely interwoven, they are not synonymous. Language refers to the production and comprehension of words, whereas speech refers to the articulatory and phonetic aspects of verbal expression (8). A disruption of language function is always a reflection of an abnormality of the brain and, more specifically of the dominant cerebral hemisphere. A disorder of speech can have a similar origin, but not always; it may be a result of abnormalities in laryngeal, pharyngeal, or lingual mechanisms (8).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you discuss the difference between slurred speech and disruption of language functioning?

- How would you describe the difference between a hemorrhagic and an ischemic stroke?

- What are the two subtypes of hemorrhagic stroke?

- Are you familiar with how TIAs are differentiated from CVAs?

Epidemiology

A sad statistic is that about one individual in the United States has a stroke every 40 seconds. Strokes cause roughly 130,000 deaths in the United States each year and many who survive become temporarily or permanently disabled (3). Stroke is the second leading cause of death across the world (3). It affects roughly 13.7 million people and kills around 5.5 million each year.

About one-third of strokes result in aphasia. An estimated 2,000,000 people are living with aphasia in the United States (5).

Risk factors of aphasia are congruent with that of strokes, as aphasia is a symptom of this medical event.

Approximately 87% of strokes are ischemic infarctions, a prevalence which increased substantially between 1990 and 2016, attributed to decreased mortality and improved clinical interventions.

The risk of having a stroke increases with age, doubling after the age of 55 years. However, studies found that strokes among people worldwide aged 20–54 years increased by about 6% between 1990 and 2016 (3). The highest reported stroke incidence is in China and the second-highest rate is in eastern Europe, while the lowest incidents of stroke occur in Latin America (3).

The prevalence of stroke in men and women depends on age. Women of younger age are impacted at higher rates, while the incidence increases with older age in men (3). This younger age factor among women correlates to complications in pregnancy, such as preeclampsia, contraceptive use, and hormonal therapy (3). Atrial fibrillation increases stroke risk in women over 75 years by 20%. Cardioembolic stroke, a more severe form of stroke, is more prevalent among women. For men, the greatest risk factors for stroke are tobacco smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, myocardial infarction, and arterial disorders (3).

Hypertension is a significant risk for stroke, specifically ischemic stroke. Additional risk factors include insufficient physical activity, poor nutrition habits, and nicotine and alcohol consumption. Differences in exposure to environmental pollutants, such as lead and cadmium, also influenced stroke incidences worldwide (3).

Studies have found a strong correlation between stroke and socioeconomic status, attributable to inadequate hospital facilities and post-stroke care among low-income populations (3).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Are you familiar with modifiable risk factors for strokes?

- Can you discuss the prevalence of strokes and the percentage of stroke survivors who experience aphasia?

- Have you witnessed aphasia in patients or loved ones?

- How does socioeconomic status correlate with post-stroke health outcomes?

Pathophysiology

Aphasia after a stroke is primarily due to damage to the brain areas responsible for language. There is a broad range of language production and comprehension functions across any or all communication modalities

Based on the pathophysiology of strokes involving the disruption of blood flow to certain parts of the brain that results in tissue damage and loss of neurological function, aphasia helps to specifically understand the location of the damage. Both types of strokes disrupt the supply of oxygen and nutrients, triggering a cascade of cellular events that include excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, and inflammation, ultimately resulting in neuronal injury and death. Nurses need to understand these mechanisms and the locations of brain impact to develop effective therapeutic strategies and improve patient outcomes.

Pathophysiology Specific to Aphasia

- Brain Regions Affected

- Broca’s Area: Located in the left frontal lobe, damage here results in non-fluent aphasia (Broca’s aphasia). Patients have difficulty with speech production but can understand language relatively well.

- Wernicke’s Area: Located in the left temporal lobe, damage here results in fluent aphasia (Wernicke’s aphasia).

- Other Areas: The arcuate fasciculus, a bundle of nerves connecting Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas, can also be damaged, leading to conduction aphasia, where patients can understand and produce speech but have difficulty repeating words and phrases.

- Neuronal Damage and Neurotransmitter Disruption

- Neuron Death: The affected neurons in these language areas die due to lack of oxygen (in ischemic stroke) or pressure and disruption (in hemorrhagic stroke).

- Neurotransmitter Imbalance: Stroke can disrupt the balance of neurotransmitters, affecting the communication between neurons, and contributing to the deficits seen in aphasia.

- Secondary Processes:

- Inflammation and Edema: Following a stroke, the inflammatory response can lead to further neuronal damage and scarring, affecting recovery and function. Edema in the brain can increase intracranial pressure, exacerbating the damage to language centers.

- Neuroplasticity:

- The brain’s ability to reorganize and form new connections can aid recovery. However, the extent and efficiency of this process vary among individuals. Rehabilitation and speech therapy can help facilitate this plasticity, improving language function over time.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What regions of the brain are involved in language processing and production?

- How can the secondary processes of inflammation cause additional damage to neural tissue?

- How would you describe the neuroplasticity of the brain?

- How do ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke symptoms differ?

Neurobiological Foundations of Language Processing

The language system of the human brain is a network of biological neurons and chemical synapses. Language processing in the brain involves a network of regions contributing to different aspects of understanding and producing language (2). Some frameworks and models dive into more specific neurobiology, but it is essential to understand the broad concept of language processing from a biological perspective.

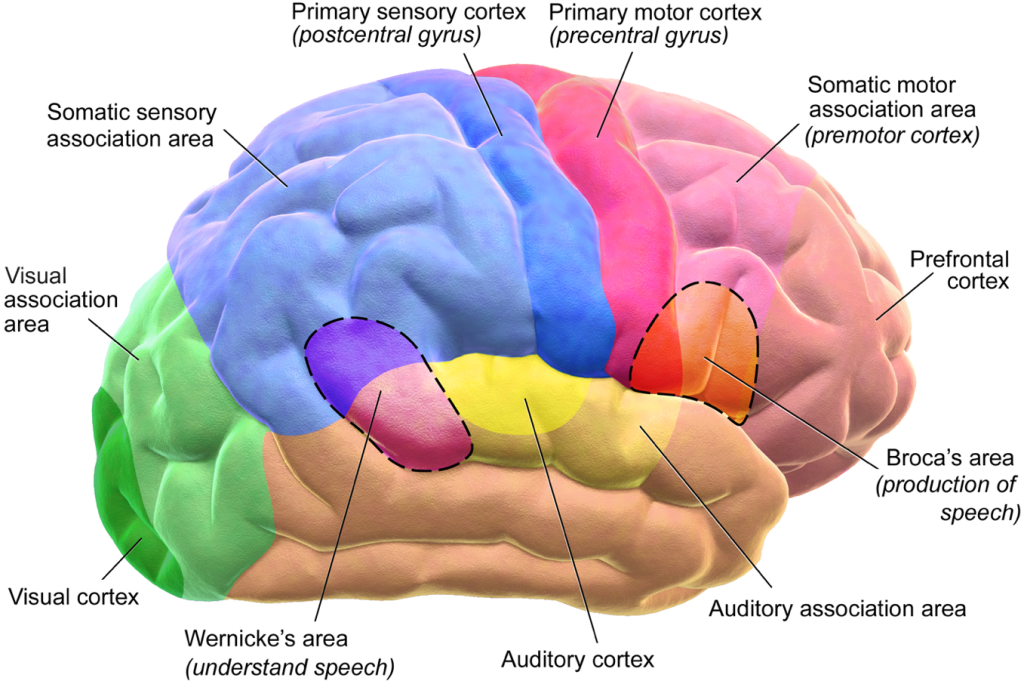

The auditory and visual cortices are responsible for the initial perception (2). The angular gyrus, a region of the inferior parietal lobe at the anterolateral region of the occipital lobe, integrates different types of sensory information. Wernicke’s Area is vital for comprehension and Broca’s Area is essential for the articulation and production of language. The arcuate fasciculus serves as the critical pathway that connects the comprehension and production areas (2). The following image represents motor and sensory regions of the cerebral cortex.

Image 1. Reference: Blausen.com staff (2014). “Medical gallery of Blausen Medical”. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436. Permission details: No permission needed, only the above citation.

Image 1. Reference: Blausen.com staff (2014). “Medical gallery of Blausen Medical”. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436. Permission details: No permission needed, only the above citation.

Assessment

In analyzing disorders of speech and language in the clinic or at the bedside, the first objective is to distinguish aphasia, which is a true impairment of language, from dysarthria, which is slurred speech.

The features of a language disorder that are used to advantage by the examiner in determining the pattern of aphasia are:

- Fluency of speech and the use of prepositions

- Correct grammar

- Comprehension of language

- The proper selection, use, and relationships between words

- Naming specific objects

- The ability to repeat in comparison to spontaneous speech

- Reading

- Writing

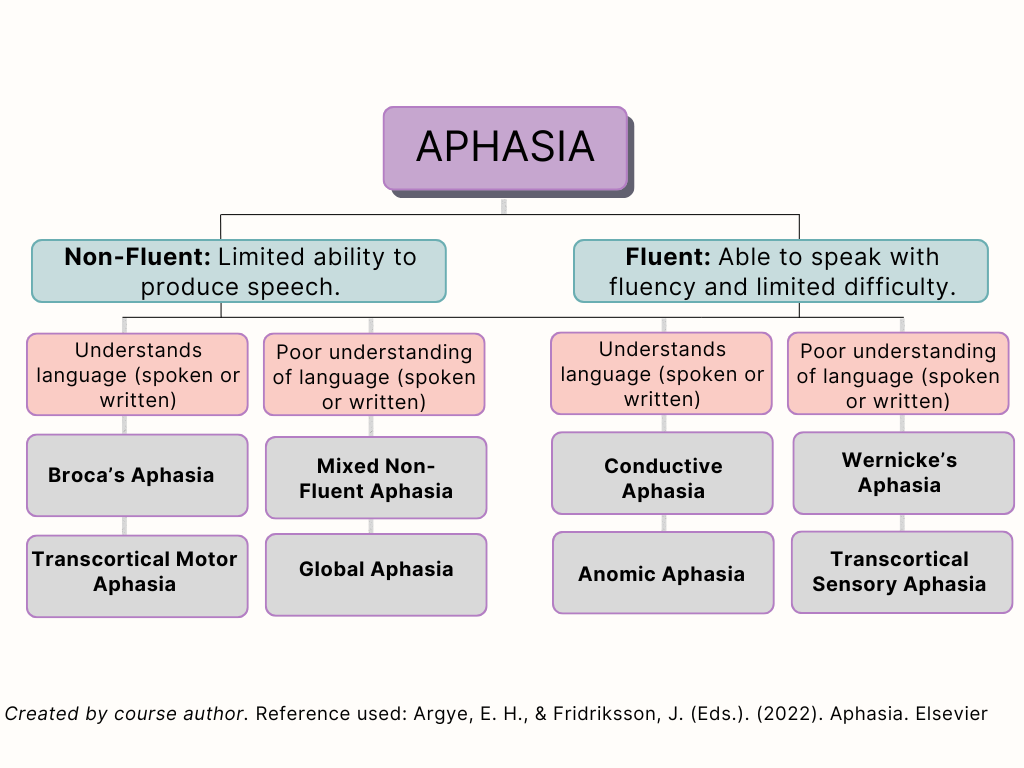

This systematic assessment will differentiate between potential types of aphasia: (1) motor or Broca aphasia, called “nonfluent,” “expressive,” “anterior”; (2) sensory or Wernicke aphasia, referred to as “fluent,” “receptive,” “posterior”; (3) a total or global aphasia, with loss of all or nearly all speech and language functions; (4) transcortical aphasia, meaning a motor or sensory aphasia with preserved repetition; or (5) a disconnection language syndrome, such as conduction aphasia, word deafness (auditory verbal agnosia), and word blindness (visual-verbal agnosia or alexia) (8)

In addition, there is a condition called mutism, which is a complete absence of verbal output. Anomia is the loss of the ability to name things. Agraphia is an impaired ability to communicate by writing (1). Agraphia rarely exists alone.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is dysarthria, and how is it distinguished from aphasia?

- What are examples of features of language to assess? (Example: ability to read, write)

- Are you familiar with other conditions that may impair fluency or articulation of speech?

- How can nurses assess comprehension of information?

Symptoms

Aphasia is a symptom of damage and injury. In this case, the injury results from a stroke.

Patients may exhibit the following symptoms:

- Speaking in short, choppy sentences

- Speaking in sentences that don’t make sense

- Substitute one word for another or mix up syllables

- Speaking unrecognizable words

- Have difficulty finding words

- Not understanding what is being said to them or written

The next section that explores the patterns of aphasia will explain the unique symptoms of each category or type of aphasia.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is a supportive way of communicating with a patient who is having difficulty finding words to express themselves?

- How would you respond if a patient is using unrecognizable words or speaking in sentences that do not make sense?

Patterns / Categories of Aphasia

Broca’s Aphasia

Broca’s aphasia is also called expressive aphasia. This involves impairment of the ability to express oneself. These patients have difficulty speaking fluently and their speech may be limited to a few words at a time; their speech is described as halting, distressing, or effortful. However, they are usually able to comprehend what is being expressed to them and maintain the ability to read. The severity ranges from mild speech impairment to a complete loss of all means of lingual, phonetic, written, and gestural communication (8).

Essentially, Broca aphasia has a primary deficit in language output and speech production but has relative preservation of comprehension (8). In the most advanced form of the syndrome, patients lose all power to speak, and the inability to speak a single word (mutism), is present.

Patients with mild to moderate Broca’s aphasia typically have limited speech (10 to 15 words per minute as compared with the normal 100 to 115 words per minute) and it consists mainly of nouns, transitive verbs, or important adjectives; it is often described as abbreviated, telegraphic character (8). In the milder forms of Broca aphasia, patients can speak aloud to some degree, but the speech seems choppy or lacking. Words can be uttered slowly and laboriously, and often words are not enunciated well.

Sometimes patients may repeat a few stereotyped utterances over and over again as if compelled to do so. Certain expressions may be said repeatedly, such as “hi,” “fine, thank you,” or “good morning.” Well-known songs may be sung by the patients.

If a patient with this type of aphasia becomes angered or excited, it is common for them to utter a curse word, thus emphasizing the fundamental distinction between propositional and emotional speech. The patient will typically recognize any verbal mistakes.

The overall impression is one of a lack of fluency, a term that has come to be almost synonymous with aphasias that derive from damage in and around the Broca area (nonfluent aphasia). This labored, uninflected speech stands in contrast to the fluent speech of Wernicke’s aphasia described later.

The naming of objects and particularly parts of objects may be named incorrectly or not at all, but the proper name can often be chosen from a list.

Wernicke’s Aphasia

Imagine playing Scrabble with someone who confidently plays words that are not technically words. However, when you play simple words, such as cat or hat, they are confused by them. This interaction is similar to an individual with Wernicke’s aphasia.

Wernicke’s aphasia is also called “fluent aphasia” or “receptive aphasia.” These individuals have an impaired ability to comprehend spoken words but can produce speech (8). However, their speech may be unintelligible, and they will probably use inappropriate words. They may not realize that they are using the incorrect words. Someone with Wernicke’s aphasia will probably have an impaired ability to read and write and lose much of their language comprehension ability.

The location of the lesion in cases of Wernicke aphasia is the left superior lateral temporal lobe (8). This damage often includes visual association areas, which results in alexia, which is an inability to read (8).

In contrast to Broca aphasia, the patient with Wernicke aphasia usually talks, gestures freely, and appears unaware of any deficits. Speech is produced mostly without effort; phrases and sentences may be of normal length. This uninterrupted and effortless speech is known as “fluency” of speech. Although the speech seems fluent, the actual content is usually void of meaning. For example, the words they use are malformed or inappropriate, a disorder referred to as paraphasia.

Verbal paraphasia, or semantic substitution, is the substitution of one word for another.

Literal paraphasia is when a syllable is substituted within a word.

Jargon aphasia is a term used to describe gibberish, or completely incomprehensible speech in Wernicke’s aphasia

Wernicke aphasia may also at times begin with complete mutism. They are not able to understand fully what is said to them. They may be able to follow a few simple commands, but there is a failure to carry out complex ones (8).

These individuals cannot read and comprehend what they are reading. Written letters are often combined into meaningless words, but there may be a scattering of correct words.

Wernicke aphasia which is caused by stroke usually improves in time (8).

Global Aphasia

Global aphasia results from cellular damage to multiple parts of the brain responsible for processing language; it is the most severe type of aphasia (1). Both Broca and Wernicke areas and much of the area between them are affected. It is most often caused by an occlusion of the proximal left middle cerebral artery; it may also be the result of hemorrhage, tumor, abscess, or other lesions (8).

In cases of global aphasia, there is a degree of right hemiplegia and hemianesthesia (8).

All aspects of speech and language are affected by global aphasia. Many are initially mute. Patients can only produce a few recognizable words. At most, the patient can say only a few words, usually a habitual phrase, and can imitate single sounds. They are not able to read, write, or repeat what is said to them. They can understand very little to no spoken language. However, they may have fully preserved cognitive and intellectual abilities that are not related to language or speech.

Global aphasia may be apparent immediately following a stroke or brain trauma. With time, some degree of comprehension of language may return as the brain heals, but there may be lasting damage.

Mixed Non-Fluent Aphasia

Patients with this type of aphasia have limited and effortful speech, similar to patients with Broca’s aphasia. However, their comprehension abilities are more limited than patients with Broca’s aphasia. They may be able to read and write, but not beyond an elementary school level.

Anomic Aphasia

A person who suffers from anomic aphasia is unable to articulate the proper words for what they want to express. Overall, they understand grammar and speech output. When they speak, it is often vague, and they might seem like they are “talking around” the thing they can’t describe. They also have trouble finding words when they write.

Primary Progressive Aphasia

This form of aphasia is not caused by a stroke. Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA) is a neurological syndrome in which an individual loses their ability to use language slowly and progressively. While most other forms of aphasia are caused by stroke, PPA is caused by neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s Disease (1).

Figure 1. Aphasia Description

Figure 1. Aphasia Description

|

Aphasia |

Fluency |

Comprehension |

Repetition |

|

Broca (expressive) |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Wernicke (receptive) |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Conduction |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Global |

No |

No |

No |

|

Transcortical motor |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Transcortical sensory |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Transcortical mixed |

No |

No |

Yes |

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you discuss why Broca’s aphasia is also called expressive aphasia?

- What pattern of aphasia would a patient experiencing complete loss of language, both comprehending and expressing, most likely have?

- What is the term for the substitution of one word for another?

- Why is Wernicke’s aphasia also called “fluent aphasia” or “receptive aphasia”?

Etiology

Symptoms can cover a range of language production and comprehension functions across any or all communication modalities (i.e., spoken language, auditory comprehension, reading, writing, and gesture).

Terminology and classifications are used to describe aphasia based on symptomology and lesion localization.

However, each case will be unique, so rigid expectations of the presentation of an individual’s impaired language processes can result in the misclassification or mischaracterization of an individual’s aphasia, which can likewise impact their care and rehabilitation. Essentially, language dysfunction is better understood in terms of a distributed network of cortical regions and subcortical connections that perform a variety of functions that support language processing and production.

While the overall pattern of speech and language impairment is somewhat predictable, lesion characteristics and individual abilities and performance can be quite variable. Classification of aphasia does not mean that specific cortical anatomy is damaged.

Treatment

Speech Therapy

Speech therapists, also known as speech-language pathologists (SLPs), play a crucial role in the treatment plan for patients with aphasia.

Here are some common methods and strategies they use (5, 10):

- Assessment:

- Evaluation of communication abilities to determine the type and severity of aphasia.

- Conduct standardized tests and assessments to identify strengths and weaknesses in language skills.

- Individualized Treatment Plans:

- Develop personalized therapy plans tailored to the specific needs and goals of each patient.

- Set realistic and achievable goals for improving communication skills.

- Alternative Communication Strategies:

- Introduce augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) devices or techniques, such as picture boards, communication apps, or gesture systems.

- Teach patients how to use these tools effectively to communicate.

- Language Therapy:

- Use exercises to improve language comprehension and expression.

- Practice naming objects, repeating words, and constructing sentences.

- Conduct conversation practice to encourage and strengthen spontaneous speech.

- Group Therapy:

- Hold group sessions to provide opportunities for social interaction and practice in a supportive environment.

- Functional Communication Activities:

- Engage and support patients in real-life activities that require communication, such as ordering food at a restaurant or making a call to their physician’s office.

- Individualize the plan for the everyday, routine communication needs of each patient.

- Provide Education and Support to Family Members and Caregivers

- Independent Practice and Exercises:

- Provide exercises and activities for patients to practice at home.

- Use technology, such as speech therapy apps, to supplement in-person therapy.

- Cognitive-Communication Therapy:

- Address related cognitive skills, such as memory, attention, and problem-solving, that can impact communication.

SLP’s goal is to improve the quality of life for individuals with aphasia by enhancing their ability to communicate effectively (10).

There is often a stage of denial or unconcern about the presence of aphasia among the patients affected (8). Reassurance and a program of speech rehabilitation are the best ways of helping the patient at this stage. Most aphasic disorders are caused by vascular disease and trauma, and they are nearly always accompanied by some degree of spontaneous improvement in the days, weeks, and months following the stroke or accident.

Studies also correlate the patient’s motivation and the interest of family and therapists to improved recovery (8). Frustration and depression, which complicate some aphasias, may require evaluation and treatment.

Research on the Management of the Cellular Impact of Stroke

The oxygen and nutrient deprivation caused by a stroke triggers a cascade of cellular events that include excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, and inflammation (1). Treatment and management that targets healing of these events can help to improve aphasia.

Neuronal death is a key manifestation of stroke, which results from neuronal depolarization and the inability to maintain membrane potential within the cell (3). The release of glutamate overpowers the system that removes glutamate from the cell and causes abnormal release of NMDA and AMPA molecules, leading to uninhibited calcium influx and protein damage.

Sodium (Na+) channel blockers: Na+ channel blockers have been used as neuroprotective agents in various animal models of stroke (3). The purpose of the drug for stroke patients is to prevent neuronal death and reduce white matter damage (3).

Calcium (Ca2+) channel blockers: Voltage-dependent Ca2+ ion channel blockers have been shown to decrease the ischemic insult in animal models of brain injury (8). In clinical trials, Ca2+ ion chelator DP-b99 proved efficient and safe in Phase I and II when administered to stroke survivors. Phase II trials significantly improved clinical symptoms in stroke survivors treated within 12 hours of onset (8). In another study, Ca2+ channel blockers reduced the risk of stroke by 13.5% in comparison to diuretics and β-blockers (8).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What methods do speech-language pathologists use to assess a patient with aphasia?

- Why is it important to tailor the assessment and treatment of aphasia to each patient?

- How can interdisciplinary teams, such as neurology, speech-language therapy, or social work, support each other?

- Can you describe the cellular reaction that occurs during cell death from a stroke?

Recommended Nursing Interventions

Each patient will have individual needs beyond aphasia, and each type of aphasia possesses distinct characteristics. The nurse should develop individualized care plans that incorporate these interventions.

Advocacy for Impaired Verbal Communication

- Collaborate with speech-language pathologists to implement specific communication strategies and techniques tailored to the patient’s needs.

- Utilize alternative communication methods

- Visual aids

- Gestures

- Communication boards

- Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) devices

- Apps

- Encourage the use of simple, concise sentences.

- Provide sufficient time for the patient to process and respond to questions.

- Provide a quiet and relaxed environment to minimize distractions and enhance communication.

Impaired Comprehension

- Use simple and concise language and sentence structure.

- Provide written instructions or visual aids to support understanding.

- Break down complex information into smaller, more manageable parts.

- Provide a calm environment and minimize distractions.

- Collaborate with speech-language pathologists to develop strategies to improve comprehension skills.

Ineffective Coping

- Assess for coping and emotional well-being.

- Provide emotional support.

- Encourage the patient to join support groups or participate in therapy, especially with those who have experienced aphasia themselves.

- Teach stress management techniques, such as deep breathing exercises or relaxation techniques, to help the patient cope with frustration.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Do you ever use visual aids in your practice?

- Can you describe a calm, relaxed environment?

- How can stress management techniques enhance therapy?

- How can technology be used to support stress management and therapy?

Research in the Field of Aphasia

Recent research has yielded several significant advances in therapeutic techniques and the potential of brain stimulation.

Brain Stimulation and Speech Therapy

Recent trials have shown promising results for combining brain stimulation with traditional speech therapy. A technique called Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) has been used to enhance the effectiveness of speech therapy. Studies have found that patients receiving tDCS alongside speech therapy showed significantly greater improvements in language abilities compared to those receiving only speech therapy. This approach has the potential to lead to major changes in rehabilitation and outcomes for those experiencing aphasia (3).

These findings are shaping the future of aphasia treatment by integrating emotional, cognitive, and technological aspects to create more comprehensive and effective therapeutic interventions.

Use of Technology: Apps for Aphasia

According to the National Aphasia Association, research shows that supplementing in-person therapy with at-home therapy via apps can facilitate recovery (6).

Apps, short for ‘applications’, can support patients with aphasia. This list of apps does not endorse any specific application or therapy, it just provides examples of available apps supporting language therapy.

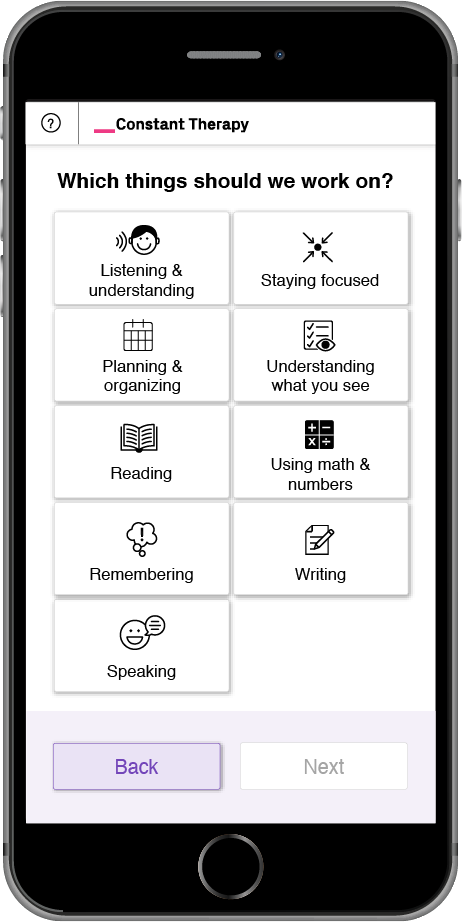

Constant Therapy

Constant Therapy is designed for people recovering from stroke and TBI, or living with aphasia, dementia, and other neurological conditions. It integrates cognitive, language, and speech therapy principles.

Image 2. App for aphasia (6)

Lingraphica

Lingraphica offers three dedicated communication devices for adults with aphasia. This application is developed from evidence-based research and may be reimbursable by insurance companies and Medicare (6).

“Words of Wisdom” from Caregivers of Those Living with Aphasia

The following advice and tips are taken from a published book that documents the responses from caregivers about what they found helpful to alleviate the stress of caring for a loved one with aphasia after a stroke (9).

“Establish some routine for yourself. This does not have to be in order, just something you do every day. This is a way you can take your daily physical and emotional temperature. Any small deviation from activity should give you pause to reflect. Here is an example from my life. I usually take a run. The daily distance varies, but if I am saying I can’t get to this, it usually means I have not made any time for myself that day. This catches up with you quickly and, in my case, it could lead to resentment toward my husband.” – Pat Phillips

“Make sure you stay in touch with friends.” – Pat Phillips

“Find humor, the support of a group, or a friend and find hope.” –Gail Soverino

“I try to do kind, unexpected acts for people during the day: comment on their nail polish, hold the door for someone, smile, give something away from my garden.” -Noreen Kepple

“Try not to overthink the future. Take one day at a time, one step at a time.” –Lorraine McPherson

“Take care of yourself. Keep up with doctors visits, and your own annual physicals. It’s hard when it seems like all you do is visit your partner’s doctors, or if you are not easily able to get away.” -JoEllen Vasbinder

Conclusion

Aphasia can be a devastating effect of a stroke, but knowledge and understanding of this condition can empower nurses to advocate for these patients. Knowledge and recognition on patterns of aphasia, symptoms, management options, and nursing considerations are key elements in providing holistic care.

References + Disclaimer

- Argye, E. H., & Fridriksson, J. (Eds.). (2022). Aphasia. Elsevier

- Hartmut Fitz, Peter Hagoort, Karl Magnus Petersson; Neurobiological Causal Models of Language Processing. Neurobiology of Language 2024; 5 (1): 225–247. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/nol_a_00133

- Kuriakose, D., & Xiao, Z. (2020). Pathophysiology and Treatment of Stroke: Present Status and Future Perspectives. International journal of molecular sciences, 21(20), 7609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21207609

- Mozeiko, J. L., & Yost, D. S. (2022). Caring for a loved one with aphasia after stroke : a narrative-based support guide for caregivers, families, and friends. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-11767-1

- National Aphasia Association. (2024). Aphasia Therapy Guide. Retrieved from aphasia.org.

- National Aphasia Association. (2024). Aphasia Apps. Retrieved from https://aphasia.org/aphasia-resources/aphasia-apps/.

- National Aphasia Association. (2024). Brain Stimulation for Treating Aphasia. Retrieved from https://aphasia.org/stories/brain-stimulation-aphasia/.

- Ropper, A. H. (2023). Adams and Victor’s Principles of Neurology (Twelfth edition). McGraw Hill Medical.

- Soverino, G. et al. (2022). Authors’ Advice to Caregivers and Families. In: Mozeiko, J.L., Yost, D.S. (eds) Caring For a Loved One with Aphasia After Stroke. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-11767-1_8

- UPMC. (2024. How a Speech Therapist Works with Aphasia Patients. Retrieved from share.upmc.com

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate