Course

Bell’s Palsy

Course Highlights

- In this Bell’s Palsy course, we will learn about the etiology and epidemiology of Bell’s palsy .

- You’ll also learn diagnostics tests that may be used to diagnose Bell’s palsy.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of the recommended treatment regimen for Bell’s palsy.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 1

Course By:

Amanda Marten, MSN, FNP-C

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

Bell’s palsy is a condition affecting the seventh cranial nerve. This condition can sometimes resemble that of a stroke, so quick assessment and evaluation are key. As well as prompt treatment of Bell’s palsy can improve client outcomes. Therefore, it’s important for nurses and healthcare providers to recognize the signs and symptoms of Bell’s palsy, diagnostic testing, treatment, and its potential complications. This course aims to equip learners with knowledge related to Bell’s palsy by reviewing its definition, epidemiology, pathophysiology, and etiology. This course also describes the signs and symptoms, diagnostic tests, and treatment related to Bell’s palsy. Lastly, it reviews potential complications and provides current research on the topic.

Definitions

Bell’s palsy: A type of facial nerve palsy or paralysis. This condition is characterized by spontaneous unilateral (causing symptoms on one side of the face) paralysis or weakness of the 7th cranial nerve (8). In rare cases, Bell’s palsy can affect both sides, causing bilateral Bell’s palsy (9).

Seven (7th) cranial nerve: Also called the facial nerve. This cranial nerve moves the muscles of the face and is responsible for the stimulation of the salivary and tear glands. It is also responsible for the tongue’s front taste buds and controlling hearing muscles (8).

Epidemiology

Approximately 23 out of every 100,000 Americans develop Bell’s palsy annually. Globally, the incidence rate of Bell’s palsy is estimated to be around 15 to 30 cases out of every 100,000 people (9). Other reports estimate a worldwide incidence rate of between 11.5 and 53.3 per 100,000 people (10). Around 10% of people who have Bell’s palsy will have a recurrence of the condition. It’s estimated that between 70% to 80% of clients with this condition will recover without treatment. However, if prompt treatment with medications is initiated, then it’s estimated that more than 95% of clients will recover (4).

This condition is common in adults, peaking between the ages of 20 and 40. Bell’s palsy affects both men and women at equal rates as well as ranges across multiple ages (9, 10). Although, women between 10-19 years old are more likely to develop Bell’s palsy than males in the same age group. Children younger than 13 years old are slightly less likely to develop this condition, while people who are 65 or older have a slightly increased prevalence (9).

In addition, women who are pregnant are roughly 3.3 times more likely to be affected by this condition than those who are not pregnant. Interestingly, Bell’s palsy more commonly occurs during the third trimester of pregnancy and the first week postpartum (6, 9).

Etiology

Originally, it was thought that Bell’s palsy was idiopathic, with no readily identifiable cause. However, ongoing research has identified certain viral infections as the cause (8). These include (6, 8, 9, 10):

- Herpes simplex virus, type 1

- Herpes zoster (also known as shingles)

- Cytomegalovirus

- Epstein-Barr virus

- Adenovirus

- Influenza

- Coxsackie

- Coronavirus (like COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2)

- Rubella

- Lyme disease

- Syphilis

In addition, sometimes cases of Bell’s palsy develop after a recent upper respiratory infection (9). Some cases of Bell’s palsy are not caused by an infection, like pregnancy-related fluid retention, or certain autoimmune disorders, like sarcoidosis and Guillain-Barre syndrome (6, 8). Also, a weakened immune system caused by stress, sleep deprivation, or other triggers can also cause this condition (5).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is the epidemiology of Bell’s palsy?

- Which populations have an increased risk of developing Bell’s palsy?

- What are some common viruses that can cause Bell’s palsy?

- How might a weakened immune system increase susceptibility to Bell’s palsy?

Anatomy and Pathophysiology

The facial nerve runs through the facial canal, which is a narrow passageway of the temporal bone. The portion of the facial canal at its narrowest has a diameter of around 0.66 millimeters (9).

The exact cause of Bell’s palsy is unknown, but there are several prevailing theories. It’s proposed that during infectious Bell’s palsy, an infection causes the facial nerve to swell, resulting in a narrow passageway for the nerve to run through. This compression of the nerve is what contributes to the symptoms of Bell’s palsy (8).

Certain autoimmune reactions can also cause the facial nerve to swell and demyelinate (destroy or loss of nerve tissue). This, again, results in the characteristic of Bell’s palsy presentation (9).

Risk Factors

Several risk factors contribute to an increased likelihood or development of Bell’s palsy. Some of these include:

- Diabetes: Clients who have diabetes are at increased risk of developing Bell’s palsy. Some reports suggest individuals with diabetes have a 29% higher risk than those without. Diabetes also impacts client outcomes as people with diabetes have a 30% higher likelihood of partial recovery than those without diabetes. Furthermore, a recurrence of the condition is more likely in clients with diabetes (9).

- Immunocompromised: Clients with autoimmune conditions or who are immunocompromised have an increased chance of developing Bell’s palsy (9).

- Pregnancy: People who are pregnant are at a higher risk of developing Bell’s palsy than those who are not pregnant (5).

- Hypertension: Some studies suggest that clients with hypertension are also at increased risk of developing Bell’s palsy. Moreover, clients who are pregnant and have preeclampsia or gestational hypertension are more likely as well (6, 9).

- Obesity: Obesity increases a person’s risk of developing Bell’s palsy (5).

- Family history: Interestingly, clients with a family history of Bell’s palsy are at an increased risk for developing the condition themselves. Some reports suggest that around 4% of clients with Bell’s palsy have a positive family history of this condition. However, further research on this subject is still ongoing (9).

In addition, Bell’s palsy can be triggered by certain factors, like impaired immunity, infections, and demyelination disorder. Dormant viral infections, like varicella or herpes simplex, can also trigger Bell’s palsy (5).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is the infectious pathophysiology of Bell’s palsy?

- What is the noninfectious pathophysiology of Bell’s palsy?

- What are some examples of risk factors for Bell’s palsy?

- Why is diabetes a risk factor for Bell’s palsy?

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

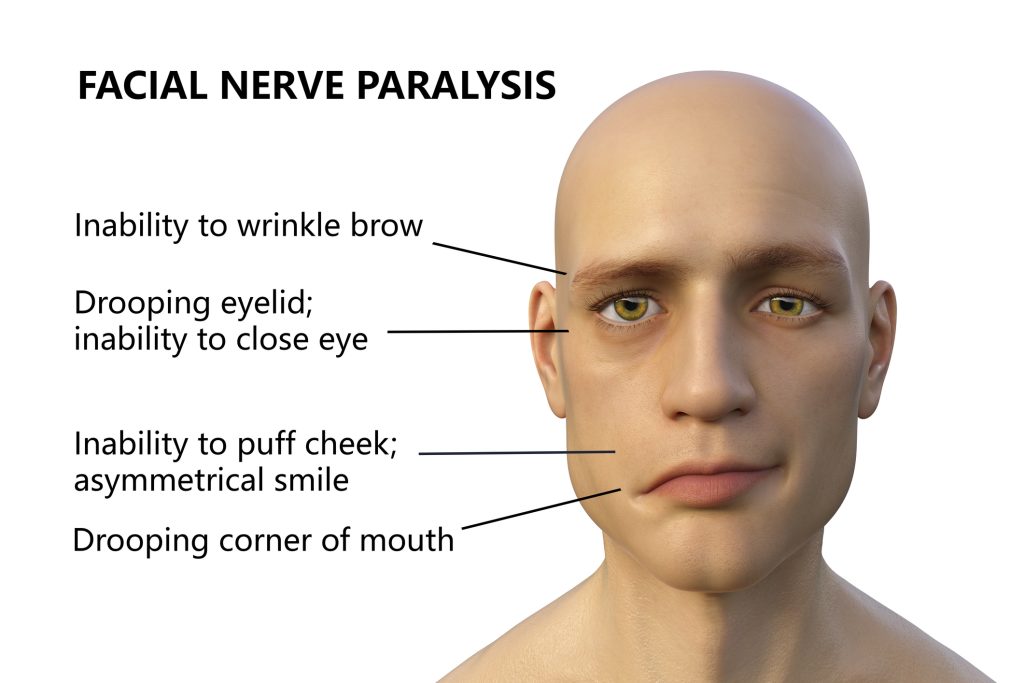

Clients with Bell’s palsy can present with a wide array of symptoms, ranging from mild facial weakness and pain behind the ear to complete unilateral facial paralysis. Interestingly, pain behind the client’s ear is often an early symptom of this condition. During the early stages of this condition, sudden unilateral facial weakness develops within a few hours (8). Other early symptoms may include (4, 9):

- Difficulty closing the eyelid

- Excessive tearing of the eye

- Ear pain

- Changes in taste

- Hypersensitivity to sounds (hyperacusis)

- Tingling sensation or numbness of the face

- Eye pain or changes to vision

Over the next 48 to 72 hours, symptoms begin to peak. Clients’ symptoms may change when compared to earlier symptoms. For example, instead of excessive tearing of the eye, the client may have decreased tearing of the eye. Facial weakness will also progress to facial paralysis, again, usually within a 48-hour period from symptom onset (9).

Additional symptoms as Bell’s palsy progresses may include (4, 8, 9):

- Inability to close the eyelid

- Inability to taste or metallic taste

- Dry eyes and mouth

- Drooling

- Facial asymmetry

Physical Exam Findings

Upon physical examination, the healthcare provider will note certain characteristics indicative of Bell’s palsy. The client’s physical exam must be comprehensive, looking for signs of other possible conditions. Other diagnoses to consider include mastoiditis, HIV infection, sarcoidosis, tumors, stroke, multiple sclerosis, Lyme disease, herpes zoster, and a constellation of others (6). Careful assessment of the head, ears, nose, eyes, throat, and skin is necessary, as well as a musculoskeletal and neurological exam, especially of the face (9).

The first clinical finding is the noticeable unilateral facial paralysis, which affects the upper and lower portions of the face. The provider may also note a flattened nasolabial fold and an inability to move one side of the forehead. Clients should be asked to smile, where the provider will note palsy to the affected side, or a distorted smile (9). Clients will also be unable to close their eyelid completely on the affected side (8). Eyebrow sagging and decreased tearing on the affected side may also be noted. The provider should also test for taste sensation and complete a thorough cranial nerve examination (6). A slit-lamp evaluation is also useful for determining ocular health, which involves looking for corneal abrasions since clients cannot completely close their eye (4).

Since Bell’s palsy resembles similar signs and symptoms of a stroke, there are some key features that help differentiate the two. What often distinguishes a typical presentation of Bell’s palsy versus a stroke is the client’s inability to move their forehead. In Bell’s palsy, clients cannot move their forehead, whereas in a typical stroke, forehead movement remains intact. However, in a brainstem stroke, forehead movement is lost. In addition, if the client has musculoskeletal or neurological symptoms or noted deficits other than the face, then the provider should suspect a stroke. Again, Bell’s palsy only affects the facial nerve, so weakness, numbness, tingling, etc., in the arms or legs do not indicate a diagnosis of Bell’s palsy but resemble those of a stroke (4, 6).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some early symptoms of Bell’s palsy?

- What symptoms change as Bell’s palsy begins to peak?

- What are the physical exam findings of a client with Bell’s palsy?

- What are the key differences between Bell’s palsy and a stroke?

Diagnostic Tests

There is no definitive diagnostic test to confirm the diagnosis of Bell’s palsy. Diagnosis can be made based on clinical presentation. However, before making a final diagnosis, the provider should consider all other possible causes before beginning treatment. Again, as Bell’s palsy can resemble a stroke, health providers must consider this a possible diagnosis. They may choose to order a STAT head CT or send the client to the emergency room, especially if clinical features and physical exam findings are not entirely clear. A brain MRI may also be completed, which can provide further detail of the brain’s structures (4, 6, 9).

Laboratory and other diagnostic tests may also be ordered to help rule out other possible etiologies. Some of these tests include (4, 6):

- Complete blood count to investigate infectious etiologies and blood counts (neutrophil and lymphocyte counts).

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein to assess for inflammatory conditions.

- Blood cultures are used to determine if there is an infectious etiology.

- Lyme titers to assess if Lyme disease is the cause of symptoms.

- Other specific blood titers to assess for conditions like HIV, syphilis, West Nile, COVID, etc.

- Lumbar puncture to analyze cerebrospinal fluid, which can help determine diagnoses like Guillain-Barre syndrome, meningitis, or sarcoidosis.

- Parotid gland biopsy, which is reserved for clients with no improvement of symptoms for several months

- Electroneuronography and electromyography studies to assess nerve and muscle function

Please note this list is not all-encompassing. Additional diagnostics tests may be ordered if another underlying etiology is suspected.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How is Bell’s palsy diagnosed?

- In what cases would a head CT or other brain imaging be ordered?

- In what cases might additional bloodwork be ordered?

Interventions and Treatment

After a diagnosis of Bell’s palsy is made, prompt treatment is recommended to improve client outcomes. The American Academy of Neurology provides guidelines and recommendations for treatment. First, clients will have better outcomes if treatment is initiated within 72 hours of the onset of symptoms. However, treatment should still be initiated even if clients are present outside the 72-hour window. Clients should be prescribed a combination of medications, including a short course of an oral corticosteroid and an antiviral. Oral steroids help to increase the potential of full recovery of the facial function (1). Oral prednisone at a dose of 60-80 mg/day is recommended for 7 days. While the efficacy of antivirals for the treatment of Bell’s palsy remains unclear, they should still be prescribed. A 7 or 10-day course of oral antivirals, such as valacyclovir or acyclovir, is also recommended. The dosing for valacyclovir is 1,000 mg three times a day for 7 days, while acyclovir is 400 mg five times a day for 10 days (1, 7). Some providers also recommend adjunct therapies, like facial massage, acupuncture, and physical therapy (5).

Clients should also be educated on the side effects of medication. For prednisone, side effects such as high blood pressure, sleep disturbances, and mood changes are common. Prescribers should also discuss the risks and benefits of the medication, especially for clients with diabetes since steroids can cause hyperglycemia (7).

Healthcare providers should also educate clients about Bell’s palsy and possible complications. Since clients with Bell’s palsy have difficulty closing their eye completely, using lubricating eye drops to prevent corneal injury is necessary. During sleep, the client should be instructed to tape their affected eye shut with a waterproof medical dressing and tap and wear an eye patch. Also, clients should be instructed that Bell’s palsy can last for several weeks, so continued follow-up is key (7).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How is Bell’s palsy treated?

- What time frame should Bell’s palsy treatment be initiated within to improve outcomes?

- What are additional care considerations for clients with Bell’s palsy?

Potential Complications

Bell’s palsy can also lead to possible complications. Some clients do not fully recover from this condition and will have permanent facial weakness (8). As the client’s affected eyelid is unable to completely shut, corneal abrasions, corneal exposure keratopathy, and other eye complications can also occur. Some clients eventually require surgery to close the affected eyelid. In addition, clients who have long-lasting facial paralysis may require surgery to aid with nerve decompression or other facial nerve and muscular complications. Botulinum toxin injections may be helpful for clients with lingering facial muscle spasticity (4).

Providers should also consider the psychological impacts of chronic facial weakness or paralysis. Clients are at increased risk for anxiety and depression (4, 7).

Current Research

There is much ongoing and current research about Bell’s palsy. Since Bell’s palsy lacks a specific diagnostic test to confirm diagnosis, there has been research studying possible new diagnostic tests. In 2024, a study by Chen et al. examined the use of quantitative electrophysical testing for early Bell’s palsy. More specifically, it evaluated the motor unit number index (MUNIX), which is a non-invasive neurophysiological test, and how it correlates with clinical findings and client prognosis. The study found that MUNIX helped evaluate early facial nerve dysfunction and Bell’s palsy severity. Therefore, it’s suggested that MUNIX can potentially be used as a reliable tool for measuring facial nerve function in early stages and cases of re-evaluation (2).

In addition, there has been much research about the treatment of Bell’s palsy. For instance, prednisone alone can be considered a first-line treatment. However, combination therapy of an oral antiviral and corticosteroid is recommended since this reduces the incidence of involuntary contractions of facial muscles (a common complication). Additionally, clients with severe facial paralysis may benefit from physical therapy to restore facial muscle function (3).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some potential complications of Bell’s palsy?

- How might this current research impact future clinical practice?

Conclusion

Bell’s palsy is an acute medical condition that if identified and treated promptly can improve client outcomes. Therefore, nurses and health providers must be diligent and able to recognize the signs and symptoms of this condition, along with the importance of prompt intervention. A thorough history and physical exam must be completed to help determine the diagnosis. If there is suspicion of a stroke, then STAT imaging is essential. Once Bell’s palsy is diagnosed, prompt treatment and reducing potential complications are crucial components of managing these clients.

References + Disclaimer

- American Academy of Neurology. (Last reviewed 2023, February 25). Evidence-based Guideline Update: Steroids and Antivirals for Bell Palsy. American Academy of Neurology. Retrieved from https://www.aan.com/Guidelines/home/GuidelineDetail/573

- Chen, M., Zhu, M., Li, X., Pi, J., & Feng, X. (2024). Motor unit number index in Bell’s palsy: A potential electrophysiological biomarker for early evaluation. Brain and behavior, 14(9), e3632. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.3632

- Dalrymple, S. N., Row, J. H., & Gazewood, J. (2023). Bell Palsy: Rapid Evidence Review. American family physician, 107(4), 415–420. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37054419/

- Hohman, M.H., Warner, M.J., & Varacallo, M. (Updated 2024, October 6). In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482290/

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (Last reviewed 2024, July 19). Bell’s Palsy. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved from https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/bells-palsy

- Ronthal, M., & Greenstein, P. (Updated 2023, October 16). Bell’s Palsy: Pathogenesis, Clinical Features, and Diagnosis in Adults. UpToDate. Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/bells-palsy-pathogenesis-clinical-features-and-diagnosis-in-adults

- Ronthal, M., & Greenstein, P. (Updated 2023, June 12). Bell’s Palsy: Treatment and Prognosis in Adults. UpToDate. Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/bells-pralsy-treatment-and-prognosis-in-adults

- Rubin, M. (Last reviewed 2023, November). Bell Palsy. Merck Manual. Retrieved from https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/brain-spinal-cord-and-nerve-disorders/cranial-nerve-disorders/bell-palsy

- Taylor, D.C. (Updated 2021, May 4). Bell Palsy. Medscape. Retrieved from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1146903-overview?&icd=login_success_email_match_fpf

- Zhang, W., Xu, L., Luo, T. et al. (2020). The etiology of Bell’s palsy: a review. Journal of Neurology 267, 1896–1905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-019-09282-4

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate