Course

Cerebral Aneurysm

Course Highlights

- In this Cerebral Aneurysm course, we will learn about the etiology and epidemiology of cerebral aneurysms.

- You’ll also learn the brain blood flow and different forms and types of cerebral aneurysms.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of the signs, symptoms, and physical exam findings of unruptured versus ruptured cerebral aneurysms.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 3

Course By:

Amanda Marten, MSN, FNP-C

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

Cerebral aneurysms occur in about 3.2% of the worldwide population (6). There are two major types of cerebral or brain aneurysms, which are unruptured and ruptured. Their treatment and management differ significantly, but regardless of the diagnosis, prompt management can help improve client outcomes. Therefore, it is essential for nurses and healthcare providers to recognize the signs and symptoms of each, as well as diagnostic testing, treatment, and potential complications. This course aims to equip learners with knowledge related to cerebral aneurysms by reviewing its definition, epidemiology, pathophysiology, etiology, and risk factors. This course also describes the signs and symptoms, diagnostic tests, and different treatment modalities for cerebral aneurysms. Lastly, it reviews potential complications and management along with appropriate nursing interventions.

Definitions

Below are relevant definitions regarding cerebral aneurysms.

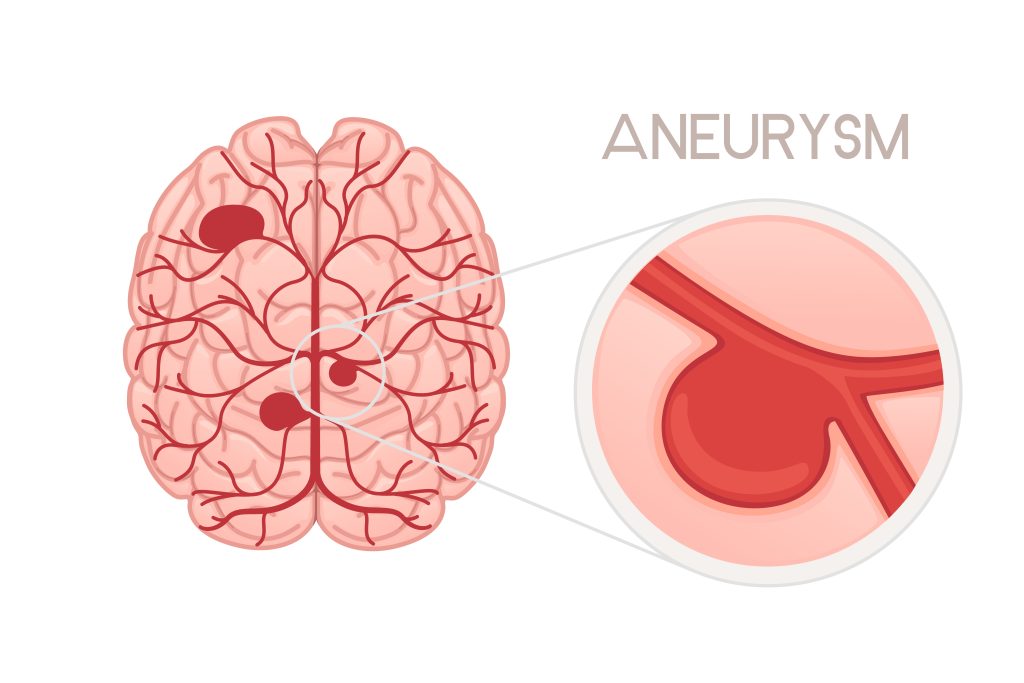

- Aneurysm: Occurs when the walls of an artery bulge (balloon or dilate) due to weakness in the blood vessel wall (1).

- Cerebral (brain or intracranial) aneurysm: Also called a brain aneurysm and intracranial aneurysm. This type of aneurysm occurs in the brain and affects the cerebral arteries. Individuals can have one cerebral aneurysm or many (1).

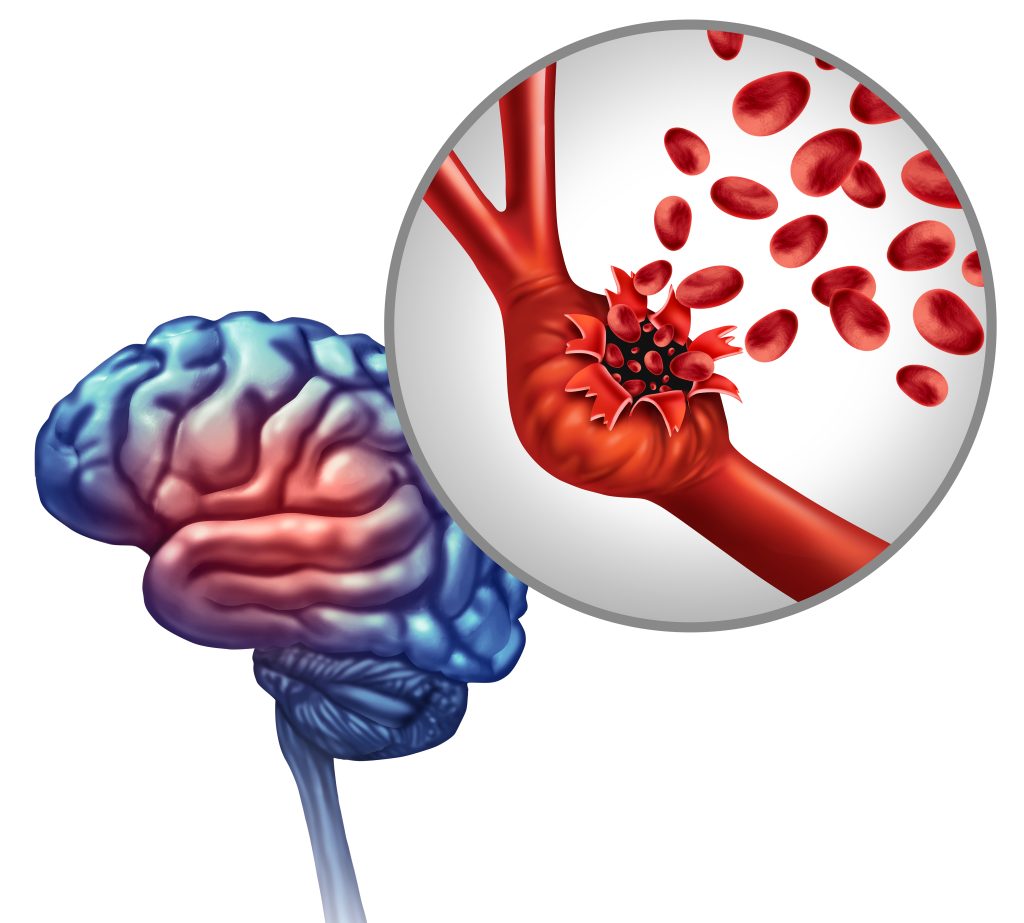

- Ruptured cerebral (brain or intracranial) aneurysm: Where the blood vessel walls become too thin from an aneurysm, causing the blood vessel to bleed (hemorrhage) or rupture. A ruptured (hemorrhagic) cerebral aneurysm is also commonly called a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). This is considered a life-threatening emergency (12).

- Unruptured cerebral (brain or intracranial) aneurysm: A brain aneurysm that has dilated or ballooned but has not begun to leak blood or rupture. However, the artery wall is still considered to be weak (12).

Epidemiology

Worldwide, about 3.2% of people have a cerebral aneurysm, with a mean client age of 50 years old (6). Furthermore, the prevalence of brain aneurysms is the highest around the 6th decade of life, and this condition is uncommon in individuals under 30 years old (12). According to the Brain Aneurysm Foundation, it’s estimated that around 6.8 million Americans have an unruptured brain aneurysm, accounting for roughly every 1 in 50 Americans (3). Other sources estimate that cerebral aneurysms occur in anywhere between 3% and 5% of the United States (U.S.) population (1). The majority of clients with brain aneurysms do not have a rupture occur. But unfortunately, some individuals with brain aneurysms will have a rupture occur, with annual estimates of around every 8 to 10 per every 100,000 annually or approximately 30,000 Americans per year. Globally, it’s estimated that about 500,000 deaths occur annually due to brain aneurysms (3). The mortality rate of clients with a ruptured cerebral aneurysm, also called a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), is high. Approximately 0.4% to 0.6% of all deaths occur from SAH (12). In the U.S., it is estimated that around 50% of clients with ruptured aneurysms will die, and about 15% to 20% will die before reaching the hospital. Of those who survive a ruptured brain aneurysm, around 66% will have some form of a permanent neurological deficit (3, 12).

In addition, cerebral aneurysms are more common in clients between the ages of around 30 to 35 and 60 years old. Women have a higher likelihood of having a brain aneurysm, with a ratio of around 3:2 (women: men) (BAF). However, some sources report a ratio of 1:1, while others report female client percentages between 54% and 61% (6, 12). Women who are older than 55 years old are 1.5 times more likely to have a ruptured brain aneurysm when compared to men (1, 3). Hispanics and African Americans also have roughly double the risk of developing a brain aneurysm when compared to Caucasians (3).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is a cerebral aneurysm?

- What are the differences between an unruptured and ruptured cerebral aneurysm?

- What populations have a higher risk of developing a cerebral aneurysm?

- What is the incidence of unruptured brain aneurysms in the United States?

- What is the mortality rate of clients with a ruptured cerebral aneurysm?

Brain Anatomy, Cerebral Blood Flow, and Aneurysms

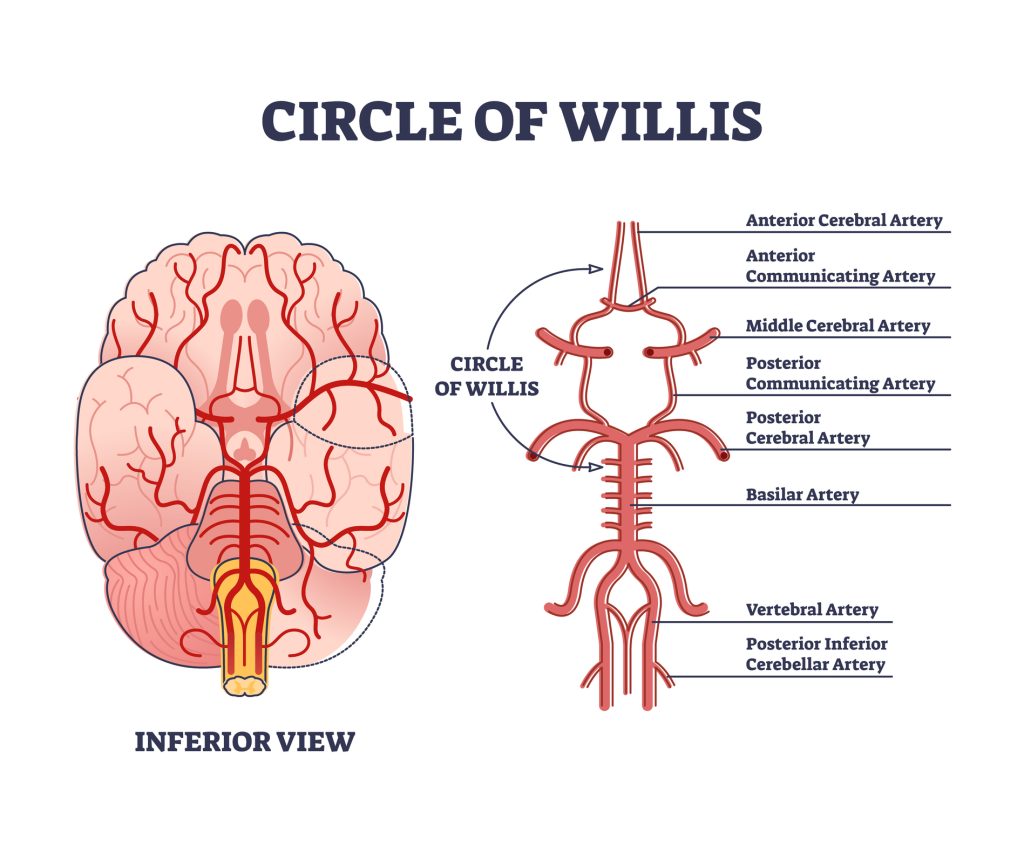

Brain aneurysms can occur anywhere in the blood vessels of the brain. Interestingly, about 20% of people with a brain aneurysm have more than one (3). Understanding how the arteries of the brain bifurcate and then converge is also helpful to brain anatomy and where aneurysms can develop. First, the internal carotid arteries (ICAs) and vertebral arteries supply the brain.

The two internal carotid arteries branch into the anterior cerebral arteries and the middle cerebral artery (MCA), which supply the anterior portion of the brain. The two MCAs supply the lateral portions of the brain. The artery that connects the two anterior cerebral arteries is the anterior communicating artery. The two vertebral arteries supply the posterior portion of the brain. These converge to form the basilar artery, which eventually splits into the posterior cerebral arteries and right posterior communicating arteries (4).

The anterior and posterior blood vessels eventually converge in the brain and form the circle of Willis. Blood vessels that make up the circle of Willis include:

- Anterior cerebral arteries (ACA): These two arteries are supplied from the two internal carotid arteries.

- Anterior communicating artery: This artery connects the two anterior cerebral arteries.

- Posterior cerebral arteries (PCA): These arteries are branches of the basilar artery.

- Posterior communicating artery: This artery connects the posterior cerebral arteries to the middle cerebral artery/internal carotids (4).

A helpful way to differentiate is to think that the communicating arteries “communicate” between the others, meaning they connect.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Which arteries supply posterior brain circulation?

- Which arteries supply anterior brain circulation?

- What is the direction of cerebral blood flow (describe the blood flow and which arteries)?

- Which arteries form the circle of Willis?

Aneurysms

Brain aneurysms come in all shapes and sizes, which helps with risk stratification. Aneurysm sizes range from less than 0.5 millimeters (mm) to 25 mm or larger. Small aneurysms are anything less than 11 mm in diameter, large are 11 to 25 mm, and giant are 25 mm or larger (8).

There are three different types, or shapes, of aneurysms. A saccular aneurysm, or berry aneurysm, is the most common. As the name implies, saccular aneurysms look like a berry hanging from a vine. Most saccular aneurysms are due to an absent or thin tunica media (middle layer of the blood vessel wall) and a lack of internal elastic lamina (fibers lining the walls of blood vessels). Fusiform and mycotic aneurysms are other types. Fusiform are sausage-shaped or circumferential (circumference or wrap around the entire artery), and mycotic are infectious and rare. Viral, bacterial, or fungal infections can cause mycotic aneurysms. Aneurysms affecting anterior brain circulation, more specifically the circle of Willis, are more common and account for roughly 85% of all aneurysms (6). Aneurysms affecting the posterior communicating artery and vertebral and basilar arteries are more likely to rupture (8).

Figure 1. Saccular aneurysm type

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How are the three major sizes of aneurysms divided?

- What are the three different types (forms) of aneurysms?

- Which type of aneurysm is the most common?

Etiology and Risk Factors

The majority of cases of brain aneurysms are acquired, meaning abnormal changes develop after birth. Certain factors predispose and increase an individual’s likelihood of developing an aneurysm. Some of these risk factors include:

- Increased age: As people age, their chances of developing a brain aneurysm increase.

- Alcohol and cocaine use: People who use alcohol and cocaine are more likely to have a cerebral aneurysm. This is most likely due to the fact that alcohol and cocaine use, especially prolonged, weaken the artery walls.

- High cholesterol/Atherosclerosis: Atherosclerosis, or plaque buildup in the arteries, can weaken the arterial walls, which leaves room for potential aneurysms to develop.

- Smoking: Smoking is likely the most significant modifiable risk factor that can increase a person’s likelihood of developing an aneurysm. Again, smoking weakens the arterial walls, which leaves room for aneurysm development (6).

- Hypertension: High blood pressure places an increased pressure on the arterial walls, which can lead to the development of weak spots. Thus, clients with hypertension, especially those who are untreated, have an increased risk.

- Family history of aneurysms: Clients with a family history of aneurysms, more especially a first-degree relative (parent, sibling, etc.), are more likely to develop a cerebral aneurysm (1, 6).

- Certain medical conditions: Specific medical conditions, such as Ehler’s Danlos syndrome, arteriovenous malformations, coarctation of the aorta, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, and others, increase a person’s risk of developing a cerebral aneurysm (6). Also, people with other genetic connective tissue disorders have a higher risk.

- Estrogen deficiency: It is suggested that female clients with estrogen deficiency have a higher risk of aneurysmal development. More specifically, post-menopausal women have a higher risk since estrogen deficiency causes the collagen content of specific tissues to decrease (12).

Other less common risk factors include tumors, trauma, and embolic-forming infections (6, 8).

In addition, several factors increase the chances of an aneurysm rupturing. These include:

- Smoking: Again, smoking increases a person’s chances of an aneurysm, but it also multiplies the likelihood of it rupturing. In fact, some studies suggest that people who smoke are three times more likely to have a brain aneurysm rupture compared to people who do not smoke, and nicotine exposure is the likely culprit that promotes aneurysmal rupture (7).

- Personal history of an aneurysmal rupture: Clients with a history of an aneurysmal rupture or SAH are at most significant risk for another rupture.

- Hypertension: High blood pressure boosts the potential of an aneurysmal rupture.

- Family history of aneurysmal rupture: Interestingly, people with a family history of aneurysmal rupture also have a higher risk of rupture themselves (8, 12).

- Aneurysm size: The larger the aneurysm, the more it is to rupture. Some studies report that aneurysm sizes over 7 mm are more likely to rupture.

- Aneurysm location: Brain aneurysms that affect specific arteries in cerebral circulation are more likely to rupture than others. Posterior circulation aneurysms (posterior communicating arteries, basilar, etc.) are the most likely to rupture. Anterior circulation aneurysms (internal carotids, anterior communicating, etc.) have an intermediate risk of rupture, while cavernous carotid artery aneurysms have the lowest risk rate.

- Multiple aneurysms: People with multiple cerebral aneurysms have a higher risk of rupture than those with a single aneurysm (12).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some risk factors for developing a cerebral aneurysm?

- What is the most significant modifiable risk factor for developing a cerebral aneurysm?

- What are some risk factors for a cerebral aneurysm rupture?

- Which type of aneurysms are more likely to rupture than others?

Pathophysiology

As mentioned, there are different types of aneurysms, with saccular being the most common. For most aneurysms, it is understood that blood flow (especially high blood pressure) through the arterial walls causes stress on the internal lamia, and turbulent blood flow pulsing leads to arterial wall breakdown over time (6).

For the fusiform and mycotic types, it is thought that this type of aneurysm is primarily caused by atherosclerosis and septic emboli, respectively (6).

Aneurysms are thought to form over several hours to weeks due to thinning and weakening in the specific brain artery’s wall at which it either ruptures or stabilizes. After the initial aneurysm growth and a rupture does not occur, further chances of rupture depend on the aneurysmal size. Those 1 centimeter (cm) or larger are more likely to continue to increase in size and subsequently rupture (12).

Figure 2. Ruptured cerebral aneurysm

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is the pathophysiology of aneurysm development?

- What is the primary cause of a fusiform aneurysm?

- What is the primary cause of a mycotic aneurysm?

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

The clinical signs and symptoms of a client with an unruptured versus ruptured cerebral aneurysm differ greatly. Therefore, these conditions are separately described below.

Unruptured Cerebral Aneurysm Signs and Symptoms

As mentioned, clients with unruptured cerebral aneurysms are often asymptomatic. They are often found incidentally or when clients present with symptoms of rupture. However, if symptomatic, they may report symptoms like: (2, 8, 12, 13)

- Headaches

- Vision changes or double vision

- Facial pain

- Seizures

- Cranial neuropathies

As the aneurysm grows and does not rupture, it can cause other symptoms, like pain behind the eye, numbness, weakness, unilateral facial paralysis, and unilateral pupil dilation (8). People with bacterial infections may present with a fever and/or weight (1).

Ruptured Cerebral Aneurysm Signs and Symptoms

Conversely, clients with a ruptured aneurysm have an array of symptoms. The most common symptom is a sudden, severe headache, which is often referred to as a “thunderclap headache,” or clients state it is the “worst headache of my life” (6). Interestingly, some sources estimate that around 1 in every 100 clients who present to the emergency department for a headache have a ruptured brain aneurysm (3). Also, about 30% of clients will have pain localized to the side of the aneurysm. Some clients may report a sudden severe headache about 6 to 20 days prior to a ruptured intracranial aneurysm or subarachnoid hemorrhage, which is called a sentinel headache or sentinel bleed. This type of headache is similar to a warning sign or “warning leak” as it is a minor hemorrhage (6). Additional symptoms of a ruptured intracranial aneurysm may include: (1, 2, 6, 8, 12, 13)

- Brief loss of consciousness at the headache onset or another period

- Drowsiness

- Confusion, stupor, or coma

- Nausea and/or vomiting

- Signs of meningismus (meningeal irritation), like neck stiffness and photophobia

- Signs of a stroke, like slurred speech, weakness, etc.

- Cardiac arrest

Seizures may also occur but are less common and occur in less than 10% of cases (6).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some signs of an unruptured cerebral aneurysm?

- Why might a client’s pupil become dilated with an unruptured cerebral aneurysm?

- What are some signs of an unruptured cerebral aneurysm?

- What is the most common symptom of a ruptured cerebral aneurysm?

- What is a sentinel headache?

- What are some signs of meningismus?

Physical Exam Findings

Clients will present with a wide range of physical exam findings depending on the timing and severity of the aneurysm and if it has ruptured. Clients with an unruptured cerebral aneurysm may lack specific physical exam findings or may have assessment findings such as:

- Elevated blood pressure/hypertension

- Pupil dilation

- Visual field deficits

- Cranial nerve deficits (6).

For clients with aneurysm rupture, physical exam findings are present and more severe when compared to an unruptured cerebral aneurysm. Physical exam findings may include: (1, 6, 11, 12, 13)

- Hypertension

- Photophobia

- Observed loss of consciousness

- Observed seizures

- Altered mental status (drowsiness, confusion, comatose)

- Neck stiffness (possibly positive Brudzinski’s and/or Kernig’s sign)

- Lower back pain with flexion of the neck

- Posturing

- Meningismus signs

- Cranial nerve deficits

- Motor deficits

- Sensory deficits

- Cranial nerve palsies

- Hemiparesis

- Ophthalmoplegia

- Bilateral hemianopia or unilateral vision loss

- Retinal, preretinal, or subhyaloid hemorrhages

Please note that this list is not all-inclusive; symptoms vary by individual and severity.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some physical exam findings of a client with an unruptured cerebral aneurysm?

- What are some physical exam findings of a client with a ruptured cerebral aneurysm?

- Why might a client have a positive Brudzinski’s or Kernig’s sign with a ruptured intracranial aneurysm?

- Why is hypertension a common physical exam finding for a ruptured cerebral aneurysm?

Screening for Cerebral Aneurysms

Most individuals with unruptured brain aneurysms are asymptomatic, so screening is paramount (especially for clients with multiple risk factors) (10). Although universal screening for every client is not recommended, the American Heart Association (AHA)/American Stroke Association (ASA) does provide clinical guidelines, with the most recent update being in 2015. The current AHA/ASA guidelines recommend screening clients who have more than one family member with an intracranial aneurysm (14). Generally, it is not recommended to screen a client with one first-degree relative with an aneurysm for an intracranial aneurysm. However, the benefits and risks should be discussed with the client to determine their best course of action (10).

In addition, it is recommended that clients with a family history of brain aneurysms and who have specific medical or genetic conditions (autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, Ehlers-Danlos type IV, coarctation of the aorta, etc.) also be screened (14). Screening of other high-risk groups is generally not recommended. Other high-risk groups include females who smoke or who have hypertension, or a combination thereof, and individuals who use tobacco and have hypertension and atherosclerosis (10). While screening is not recommended for these high-risk groups, the healthcare provider should use their best judgment and shared decision-making with the client to determine the best care plan.

Screening for a cerebral aneurysm entails a noninvasive computed tomography angiogram (CTA) with intravenous contrast or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the head. These screening tests can typically detect aneurysms of 5 mm or larger. For clients allergic to intravenous contrast, MRA may be preferred. Conversely, if the client has contraindications to an MRA, then a CTA with contrast may be the preferred screening test (10, 14).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are the current AHA/ASA intracranial aneurysm screening guidelines?

- If a client has one first-degree relative with an intracranial aneurysm, is screening recommended and why?

- What screening tests are performed on clients who meet the cerebral aneurysm screening guidelines?

- What scenarios might a CTA with contrast versus an MRA be ordered for screening?

Diagnostic Tests

For clients with a suspected aneurysm, diagnostic testing is recommended. For individuals where screening is recommended, MRA or CTA with contrast is the preferred test. In some cases, conventional angiography may be performed as well (6).

For clients presenting with an acute onset non-traumatic headache with peaking intensity within one hour, a helpful decision-making tool is the Ottawa Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Rule. In addition, this tool is used for alert clients who are older than 15 years of age and again presenting with a non-traumatic headache with peaking intensity within one hour. If clients meet any of the following criteria, further investigation with imaging is warranted: (5, 13)

- Client is 40 years of age or older

- Has neck pain or stiffness

- Had a witnessed loss of consciousness

- Onset occurred during exertion

- Client reports a “thunderclap headache”

- Client has limited neck flexion

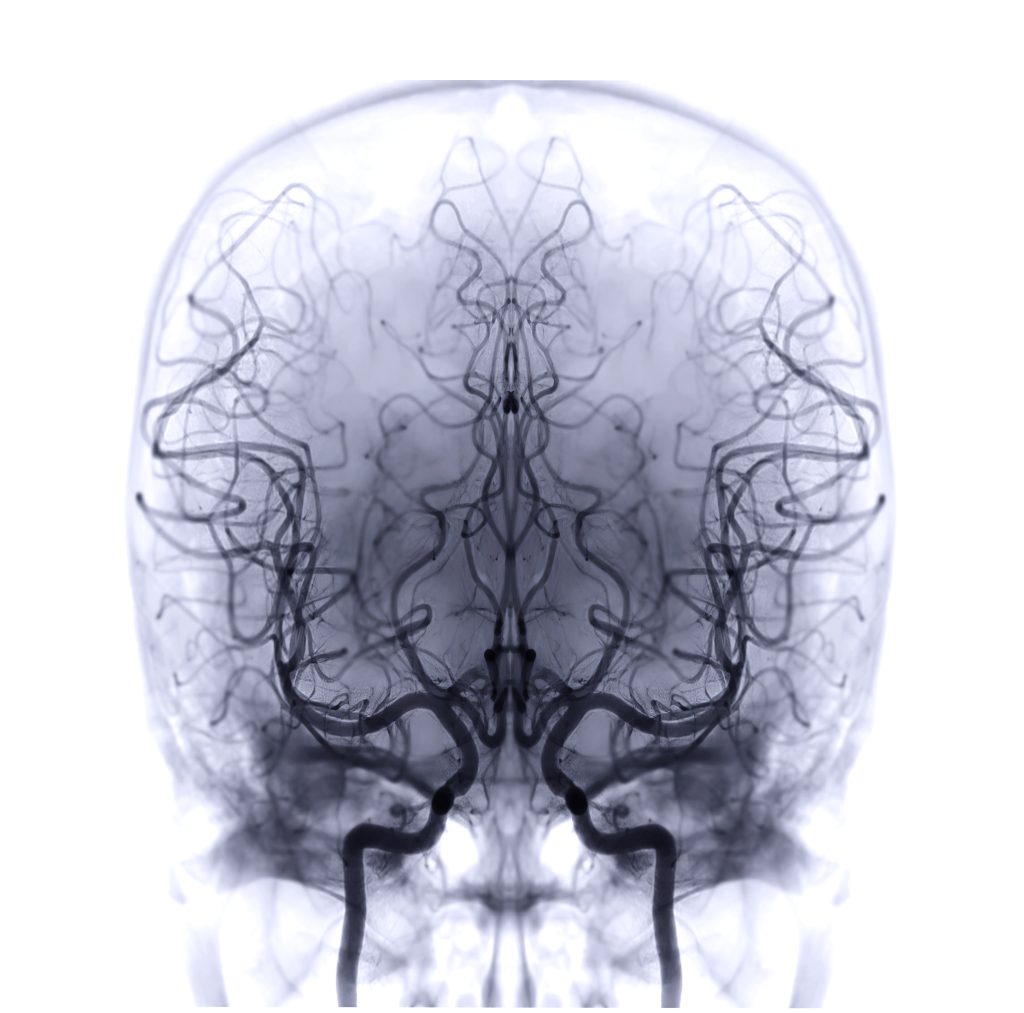

For clients with a suspected subarachnoid hemorrhage, STAT CT imaging of the brain without contrast is the diagnostic test of choice. If the initial CT scan returns negative, then a lumbar puncture should be performed to absolutely rule out an SAH. The lumbar puncture results of a client with an SAH would reveal an elevated opening pressure and red blood cell count along with xanthochromia (yellow or pink tint of the cerebrospinal fluid). This cerebrospinal fluid color change is a result of the breakdown of hemoglobin products. After diagnosis with a lumbar puncture is made, additional follow-up imaging is necessary. Follow-up imaging may include CT angiography, MRA, or digital subtraction angiography (DSA) of the head/brain. The gold standard of imaging for the detection of an aneurysm and/or SAH is performing DSA. This method entails placing an arterial catheter and injecting contrast for fluoroscopy (5, 6, 14).

Image 1. Brain fluoroscopy

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are the criteria for the Ottawa Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Rule?

- What is the initial diagnostic test recommended for clients with a suspected SAH?

- What key features in a lumbar puncture indicate an SAH?

- What is the gold standard diagnostic test for a client with an aneurysm?

Use of Grading Scales For Cerebral Aneurysms

Other grading scales and tools may be utilized in clinical practice to determine the severity and risk of vasospasm or rupture to support clinical decision-making and treatment planning. These are further subdivided into unruptured versus ruptured scales and tools.

Grading Scale for Unruptured Cerebral Aneurysms

First, for clients with an unruptured brain aneurysm, several scoring tools are available and may be used. However, strong validation of these tools has not been studied, and thus, these tools have not been adopted into the standard of care. First, the PHASES (population, hypertension, age, size of aneurysm, and earlier SAH) score helps estimate the likelihood of aneurysmal rupture within a five-year period. This tool assigns a certain number of points per category. For the population category, Japanese individuals are assigned 3 points, Finnish are assigned 5 points, and all other populations earn 0 points. Next, if the client has hypertension, they earn 1 point, and if they are 70 years or older, they are also assigned 1 point. If they’ve ever had an SAH, then they earn 1 point as well. The category of aneurysmal size is divided into less than 7 mm, 7 to 9.9 mm, 10 to 19.9 mm, and 20 mm or more, where individuals are assigned 0, 3, 6, and 10 points, respectively. Lastly, the site of the aneurysm, whether located in the internal carotid artery, middle cerebral artery, anterior cerebral arteries, posterior communicating artery, or posterior circulation, earns 0, 2, or 4 points. Once the client’s score is totaled, a total score of 5 or less is low risk, and scores 12 or greater have a higher risk of aneurysmal rupture (9, 12).

The ELAPSS (Earlier Subarachnoid Hemorrhage, Aneurysm Location, Age, Population, Aneurysm Size and Shape) scoring system is used to evaluate the risk of unruptured cerebral aneurysmal growth within the next 3 to 5 years. Again, this scoring system assigns points for certain features. It takes into account prior SAH, the location of the aneurysm, the client’s age, population, the size of the aneurysm, and the aneurysmal shape. Total scores of less than 5 have a 3-year growth risk of 5% and a 5-year risk of 8.4%. Clients with scores totaling 25 or greater have a 3-year risk of growth of 42.7% and 60.8% for 5 years (9).

Last, the Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysm Treatment Score, or UITAS, helps guide client treatment and management for clients with an unruptured cerebral aneurysm. This scoring system is comprehensive, taking into account many variables that are divided into subcategories. Overarching client variables include client risk, multiple risk factors (prior SAH, smoking, drug use, alcohol use, family history, etc.), the presence of clinical symptoms, life expectancy due to chronic disease or malignancy, client comorbidities, and other factors. Aneurysm variables include diameter, morphology, location, and other factors. Treatment variables include age-related risk, aneurysm size-related risk, and aneurysm complexity-related risk. Each positive subcategory is assigned points for either columns T (treatment/intervention) or C (conservative management). The client’s points for columns T and C are totaled for each. If there is more than a 3-point difference between T and C, then the outcome favors the higher score. If the difference is 2 or less, then the tool is inconclusive (9).

Grading Scales For Ruptured Cerebral Aneurysms/SAH

For clients with a suspected or confirmed SAH, there are many available clinical decision tools. First, the World Federation of Neurological Surgeons scale is a grading scale used to determine SAH severity. This scale combines the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and the client’s neurological deficits to predict SAH severity. The grades range from 1 to 5, with a grade of 1 being the lowest severity and 5 being the most severe (5, 13).

In addition, the Hunt and Hess grading scale is used to predict the survival of clients with SAH. This scale assigns a score of 1-5 depending on the client’s neurological status. Clients with a score of 1 (asymptomatic or mild headache and nuchal rigidity) have the highest survival rate, while clients with a grade of 5 (decerebrate posturing, comatose) have the lowest survival rate (5, 13).

The Fisher scale helps assess the client’s risk of cerebral vasospasm based on the appearance of blood on the head CT. This scale has groups 1 through 4, with group 1 showing no blood detected and group 4 showing an intracerebral or intraventricular clot with or without subarachnoid blood (13).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is the PHASES score?

- What is the ELAPSS score?

- What is the UIATS score?

- What is the World Federation of Neurological Surgeons scale?

- What is the Hunt and Hess scale?

- What is the Fisher scale?

Interventions and Treatment

The tools and scoring systems mentioned above help guide intracranial aneurysm treatment, whether unruptured or ruptured. Since client management and guidelines differ greatly between the two, treatment for an unruptured versus ruptured brain aneurysm is divided below.

Unruptured Brain Aneurysm

The treatment of unruptured cerebral aneurysms is further subdivided into asymptomatic versus symptomatic. For clients without risk factors and who are asymptomatic with an aneurysm less than 7 mm in size, conservative treatment is recommended. Again, providers can use the PHASES, ELAPSS, and/or UITAS scoring systems to aid with the best course of management and their plan of care. Conservative management encompasses educating the client regarding the risk of an SAH, managing the client’s hypertension, discussing smoking cessation, and avoiding certain activities. Furthermore, these clients should undergo routine monitoring and imaging to track aneurysmal growth, if any. Repeat imaging (CTA or MRA) is reasonable within the first 6 months of a new diagnosis, and thereafter, annual imaging is helpful for the first two or three years if the aneurysm is stable (12, 14).

Clients with symptomatic unruptured aneurysms should undergo interventional treatment, which entails surgical and endovascular interventions (12). First, surgical clipping may be indicated. This procedure involves placing a clip along the neck of the aneurysm (11). The AHA/ASA surgical clipping recommendations also provide guidance on the matter. These organizations state that they ensure accounting for client factors and perform long-term follow-up imaging after surgical clipping. It is recommended that surgical clipping is performed at high-volume hospitals, typically performing more than 20 cases annually. Also, the use of specialized intraoperative tools to avoid vessel compromise is recommended. After the surgical clipping procedure, they also recommend immediate imaging for documentation of aneurysm obliteration (14).

Endovascular treatment may also be performed on clients with unruptured cerebral aneurysms. This technique involves coil embolism, where platinum coils are placed inside the aneurysm’s lumen. The coil causes a localized thrombus to form around the coil, causing the aneurysmal sac to become obliterated (11). Other newer endovascular treatments are endoluminal flow diversion and liquid embolic agents. However, their use is cautioned because their long-term effects are largely unknown and understudied. Again, this procedure should be performed at high-volume surgical facilities, and the risk of radiation exposure must also be discussed with the client during consent (14).

The AHA/ASA guidelines currently consider surgical clipping and endovascular coiling effective treatment methods. Clients must be fully informed of the risks and benefits of each procedure prior to their decision and consent. While endovascular coiling reduces client risk of morbidity and mortality when compared to surgical clipping, the risk of aneurysm reoccurrence is higher (14).

Ruptured Brain Aneurysm (Subarachnoid Hemorrhage)

As a subarachnoid hemorrhage is a life-threatening emergency, immediate diagnosis and treatment is warranted. The AHA/ASA provides several treatment guidelines on the matter of ruptured cerebral aneurysms. Guidelines discuss the timing, treatment goals, treatment modalities, and endovascular adjuncts. First, surgical or endovascular intervention should be formed as early as possible to improve clients’ morbidity and mortality. Complete obliteration of the aneurysm is indicated whenever feasible. However, sometimes, this form of treatment is not feasible, so partial aneurysm obliteration may be considered, but the risk of rebleeding is higher. Modalities of treatment depend on the aneurysm location and morphology. For aneurysms involving posterior circulation, coiling is preferred, and for anterior circulation, coiling is the preferred method if the client is eligible for either intervention. If the client has a reduced level of consciousness from intraparenchymal hematoma, emergent clot evacuation is warranted. For clients under 40 years of age, surgical clipping may be preferred. Since the treatment recommendations are complex, the providers and surgeons must diligently weigh the risks and benefits and discussing these with the client. The neurosurgeon(s) must share in clinical decision-making with the client as well (5).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is the recommended treatment for clients with asymptomatic unruptured cerebral aneurysms?

- What is the recommended treatment for clients with symptomatic unruptured cerebral aneurysms?

- What are the differences between surgical coiling and endovascular interventional treatment?

- What is the recommended treatment for clients with ruptured cerebral aneurysms?

- What are some factors the neurosurgeon must consider when determining treatment?

Potential Complications of a Ruptured Cerebral Aneurysm

There are several serious complications of ruptured cerebral aneurysms. Some of these include: (6, 8)

- Rebleeding: Aneurysms have the potential to re-rupture before or after interventional treatment.

- Hydrocephalus: Excess cerebrospinal fluid in the brain causes hydrocephalus, which can lead to increased intracranial pressure. This is life-threatening and can result in a coma or even death if left untreated.

- Vasospasm: Arteries in the brain can constrict and contract, which limits blood flow to the brain. Sometimes, this can lead to a stroke and/or brain ischemia.

- Sodium imbalances: Blood supply to the brain is impacted with a SAH, which leads to sodium imbalances resulting in swelling of the brain. Thus, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) is a potential complication.

- Seizures: Bleeding and increased intracranial pressure can result in seizures

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some potential complications of an SAH?

- Why are clients at risk for rebleeding?

Managing Potential Complications

The management of potential complications is also paramount to improve client outcomes. For clients with SAH and respiratory failure who require mechanical ventilatory support, intensive care bundles and precautions to reduce the risk of hospital-acquired pneumonia are recommended. In addition, for clients who develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), prone positioning and intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring may be helpful in improving oxygenation. The client’s volume status is also important, where either excess or too little fluid can potentially lead to complications and sodium imbalances. Glycemic and temperature monitoring and control are also necessary. Lastly, once the client has undergone interventional treatment for SAH, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis is recommended either mechanically or pharmacologically (5).

Cerebral Vasospasm Monitoring and Management

Cerebral vasospasm can occur in clients with SAH and can lead to delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI) or infarction. So, monitoring for the potential of this condition is essential as well. CTA or CT perfusion imaging helps detect vasospasm and DCI. Additionally, transcranial Doppler ultrasound is helpful as well as continuous electroencephalography (EEG) monitoring. Invasive neuromonitoring techniques (lactate, pyruvate, and glutamate concentrations) may also be used (5).

To manage cerebral vasospasm, nimodipine (an IV antihypertensive medication) is helpful. Clients with severe vasospasm and SAH will likely benefit from intra-arterial vasodilators. Other treatment modalities should be avoided or are not recommended per the AHA/ASA guidelines, which include statin therapy, IV magnesium, and prophylactic hemodynamic augmentation (also known as triple H therapy that intends to improve brain perfusion by increasing a client’s mean arterial pressure, or MAP, and decreasing viscosity of the blood) (5).

Managing Hydrocephalus and Seizures

For clients with hydrocephalus, increased intracranial pressure is a major concern. So, urgent CSF diversion via an external ventricular drain (EVD) or lumbar drain is necessary. Additionally, EEG monitoring may also be a reasonable consideration. Clients with hydrocephalus or who are at high seizure risk for other reasons may benefit from preventative seizure medications. However, clients not considered high-risk may not have benefited from antiseizure medications (5).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some methods used to manage potential complications from SAH?

- Why is glycemic control important for clients with SAH?

- What modalities may be used to monitor cerebral vasospasm?

- What modalities may be used to treat cerebral vasospasm?

- What are some management considerations related to clients with hydrocephalus and/or seizures?

Nursing Interventions

There are many nursing interventions that must be implemented for clients with cerebral aneurysms, especially for those with SAH. Following evidence-based protocols is recommended to provide quality and effective care. Clients are admitted to the intensive care unit for frequent monitoring of the client’s neurological status, including the Glasgow Coma Scale and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, and other checks. The nurse may assess the client’s level of consciousness, pupillary response, pain response, motor strength, sensation, cranial nerve function, reflexes, etc. Additionally, frequent monitoring of client vital signs is warranted. Neurological checks and vital signs are usually assessed at least hourly for the first 24 hours post SAH intervention. Nurses must adhere to strict stroke protocols as well. Other nursing interventions may include elevating and maintaining the client’s head of bed at 30 degrees or more, EVD monitoring and draining, ICP monitoring, and others (5).

The nurse must also administer any ordered medications and continuous intravenous medications. These may include but are not limited to antihypertensives, continuous IV fluids, antiseizure medications, and others. The nurse should monitor the client’s lab values, including sodium, potassium, hemoglobin, hematocrit, and others, for any imbalances and promptly notify the appropriate overseeing provider. Before the initiation of any oral intake, a dysphagia screening must be completed to reduce the likelihood of pneumonia. Depending on the healthcare facility, this may be performed by speech therapy, the nurse, or another specialist. In addition, early mobility helps to improve the client’s level of functioning. Therefore, occupational and physical therapy may also be ordered and performed. Clients may need psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy for depression, anxiety, or other mental health concerns. Care of clients with an SAH requires a well-coordinated multidisciplinary team (5).

These interventions are not all-encompassing, and other aspects of care are still performed by the nurse.

Client Recovery and Prognosis

For clients with a ruptured cerebral aneurysm, prognosis is typically poor and depends on an array of factors. Most clients will require several weeks to months of continued outpatient care. Follow-up with neurosurgery, neurology, primary care, and other allied health professionals can help improve client outcomes and prognosis (6).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Why would a nurse perform frequent neurological checks on a client after SAH intervention?

- What lab values should a nurse especially monitor for clients with SAH?

- What other nursing interventions might the nurse include in their care?

Conclusion

Unruptured cerebral aneurysms should be closely monitored and assessed. For clients with a ruptured cerebral aneurysm, emergent medical attention is warranted since this is a life-threatening condition and, if treated promptly, can improve client outcomes. Nurses and health providers must be diligent and able to recognize the signs and symptoms of an SAH condition, along with the importance of prompt intervention.

References + Disclaimer

- Alexandrov, A.V., & Krishnaiah, B. (Last reviewed 2023, June). Brain Aneurysms. Merck Manual. Retrieved from https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/brain-spinal-cord-and-nerve-disorders/stroke/brain-aneurysms

- American Association of Neurological Surgeons. (2024, April 26). Cerebral Aneurysm. American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Retrieved from https://www.aans.org/patients/conditions-treatments/cerebral-aneurysm/

- Brain Aneurysm Foundation (2023, August). Brain Aneurysm Statistics and Facts. Brain Aneurysm Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.bafound.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Stats-and-Facts_download.pdf

- Gofur, E.M., & Bordoni, B. (Updated 2023, July 17). Anatomy, Head and Neck: Cerebral Blood Flow. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538134/

- Hoh, B.L., Ko, N.U., Amin-Hanjani, S., Chou, S.H., Cruz-Flores, S., Dangayach, N.S., Derdeyn, C.P., Du, R., Hanggi, D., Hetts, S.W., Ifejika, N.L., Johnson, R., Keigher, K.M., Leslie-Mazwi, T.M., Lucke-Wold, B., Rabinstein, A.A., Robicsek, S.A., Stapleton, C.J., Suarez, J.I., Tjoumakaris, S.I., & Welch, B.G. (2023). 2023 Guideline for the Management of Patients with Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/ American Stroke Association. American Heart Association Journals 54 (7). https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000436

- Jersey, A.M., & Foster, D.M. (Last updated 2023, April 3). Cerebral Aneurysm. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507902

- Kamio, Y., Miyamoto, T., Kimura, T., Mitsui, K., Furukawa, H., Zhang, D., Yokosuka, K., Korai, M., Kudo, D., Lukas, R. J., Lawton, M. T., & Hashimoto, T. (2019). Roles of Nicotine in the Development of Intracranial Aneurysm Rupture. Stroke, 49(10), 2445–2452. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.021706

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (Last reviewed 2024, July 19). Cerebral Aneurysms. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved from https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/cerebral-aneurysms

- Sanchez, S., Miller, J.M., & Samaniego, E.A. (2023). Clinical Scales in Aneurysm Rupture Prediction. American Heart Association Journals 4 (1). https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/SVIN.123.000625

- Singer, R.J., Ogilvy, C.S., & Rordorf, G. (Last reviewed 2024, November). Screening for Intracranial Aneurysm. UpToDate. Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/screening-for-intracranial-aneurysm

- Singer, R.J., Ogilvy, C.S., & Rordorf, G. (Last reviewed 2024, November). Treatment of Cerebral Aneurysms. UpToDate. Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-cerebral-aneurysms

- Singer, R.J., Ogilvy, C.S., & Rordorf, G. (Last reviewed 2024, November). Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms. UpToDate. Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/unruptured-intracranial-aneurysms

- Singer, R.J., Ogilvy, C.S., & Rordorf, G. (Last reviewed 2024, November). Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Clinical manifestations and Diagnosis. UpToDate. Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/aneurysmal-subarachnoid-hemorrhage-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis

- Thompson, B.G., Brown, R.D., Amin-Hanjani, S., Broderick, J.P., Cockroft, K.M., Connolly, S., Duckwiler, G.R., Harris, C.C., Howard, V.J., Johnston, S.C., Meyers, P.M., Molyneux, A., Ogilvy, C.S., Ringer, A.J., & Torner, J. (2015). Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/ American Stroke Association. American Heart Association Journals 46 (8). https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000070

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate