Course

Colon Cancer Screening and Clinical Diagnosis

Course Highlights

- In this Colon Cancer Screening and Clinical Diagnosis course, we will learn about the anatomy and physiology of the colon and rectum.

- You’ll also learn risk factors, epidemiology, clinical presentation, and different stages of colon cancer.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of current colon cancer screening guidelines.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 3

Course By:

Abbie Schmitt, MSN-Ed, RN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

Welcome to the Colon Cancer Screening and Clinical Diagnosis course—where saving lives starts with early detection. Colon cancer is one of the most preventable cancers, yet it is often caught too late. Nurses have a meaningful role in encouraging screening, which can be the difference between early diagnosis and advanced disease.

Throughout this course, we’ll explore colorectal cancer, the anatomy and physiology of the colon, and screening methods like colonoscopies, FIT tests, and sigmoidoscopies. We will dive into the latest guidelines, address barriers to screening, and examine real-life case studies that show just how impactful early detection can be.

As trusted client advocates, you have a unique opportunity to transform statistics into survival stories. Let’s embark on this journey together to make colon cancer a thing of the past—one screening at a time!

Overview of Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer is a type of cancer that begins in the colon or rectum, which are parts of the large intestine. This cancer typically starts as polyps, which are small growths on the inner lining of the colon or rectum. Over time, some of these polyps can become cancerous. The exact cause of colorectal cancer is not always clear, but certain factors such as age, lifestyle, family history, and genetic mutations increase the risk. Symptoms of colorectal cancer may include changes in bowel habits, blood in the stool, abdominal pain, and unexplained weight loss.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology is a field of science that examines the determinants and distribution of a disease in a specific population (12). Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related mortalities (1, 5). It is the second most frequently diagnosed cancer in women and third in men.

The American Cancer Society (ACS) reports approximately 152,810 new cases of colorectal cancer in 2024; with 106,590 cases of colon cancer, and 46,220 rectal cancer cases. CRC is the second leading cause of all cancer-related deaths in the U.S., with an estimated 53,010 deaths in 2024, a slight increase over last year’s estimated 52,550.

- Rate of New Cases and Deaths: The rate of new cases of colorectal cancer was 36.5 per 100,000 men and women per year. The death rate was 12.9 per 100,000 men and women per year.

- Lifetime Risk of Developing Cancer: Researchers estimate that 4% of men and women will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer at some point during their lifetime.

- Prevalence of This Cancer: In 2021, an estimated 1,392,445 people were living with colorectal cancer in the U.S.

(5, 14)

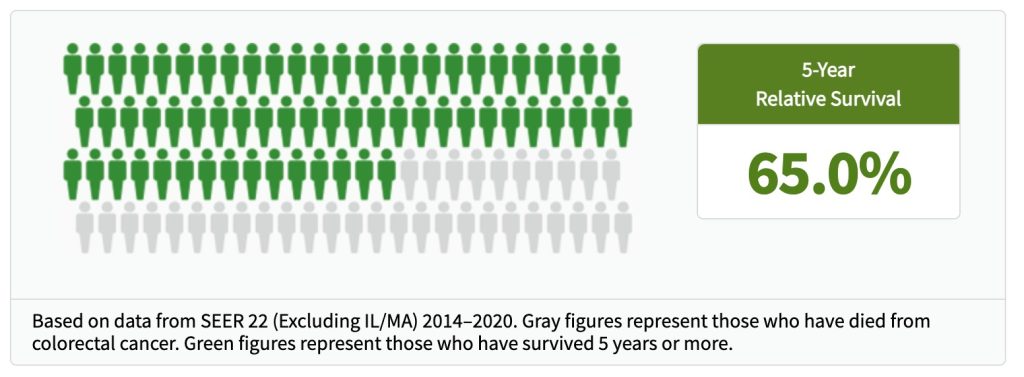

Survival statistics are based on large groups of people and data and cannot be used to predict exactly what will happen to individual clients, responses to treatment can vary greatly. However, the National Cancer Institute projects that 65% of newly diagnosed CRC cases will survive for five years (14).

Figure 1. Colon Cancer 5-Year Relative Survival (14)

The incidence of CRC varies according to age, sex, race, and geographical disparities. CRC is more commonly diagnosed in males than in females (5, 12).

Certain racial groups face a higher incidence as well. In the U.S., Black Americans are 15% more likely to develop colorectal cancer and 35% more likely to die from it than non-Hispanic white individuals (1). Those among Alaskan Native ethnicity have the highest colorectal cancer incidence and mortality rates globally (1).

These disparities have led to the need for healthcare professionals, policymakers, and the public to facilitate a targeted approach to foster health equity in colorectal cancer prevention and management. The incidence of CRC varies geographically due to lifestyle features and social determinants of health (SDOH).

Risk Factors

Individual risk factors, such as a family history of colorectal cancer, inherited genetic disorders, or certain lifestyle factors, may increase the likelihood that a person will develop CRC. The risk of CRC increases with age.

Non-modifiable risk factors. These are characteristics or conditions that increase the likelihood of developing colorectal cancer but cannot be changed or influenced by lifestyle or behavior modifications. These risk factors are inherent and typically involve genetic, biological, or environmental elements. Age, gender, medical history, and family medical history are non-modifiable risk factors (1).

- Age – this risk of CRC is suggested to increase with age.

- Researchers estimate that the incidence of CRC approximately doubles every 5 years until 50 years of age, while a nearly 30% increase is detected among individuals of the age group of 55 years and older (12).

- Additionally, the incidence for the age groups varies with the anatomical site. For instance, among CRC clients, half of the population aged 65 years and older had proximal colon cancer, while those 50 years and younger presented with distal colon cancer.

- A personal history of bowel diseases like Crohn’s disease

- Family History of CRC or polyps

- Genetic disorders like Lynch syndrome

- Type 2 diabetes

Modifiable risk factors. More than half of colorectal cancer cases can be attributed to potentially modifiable risk factors. These factors include: (1)

- Excess body weight

- Tobacco use

- Heavy alcohol intake

- High intake of red or processed meat

- Physical inactivity

- A diet low in calcium, whole grains, and/or fiber

Physical activity, limiting alcohol consumption, and maintaining a diet low in animal fats and high in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains can reduce the risk of CRC.

Trends in CRC

Survival rates among those diagnosed with colorectal cancer have improved over the past few decades, which is attributed to less smoking, more screenings, and advanced treatments. The death rate has dropped by 55% in men since 1980 and 60% in women since 1969 (1).

Although CRC among older adults is on the decline, there is a trend of increased colon cancer among younger people. CRC diagnoses have risen about 1% and 2% each year in those under the age of 55 since the mid-1990s. The mortality rate in young people is also increasing about 1% each year since the mid-2000s (1). Colorectal cancer has now become the leading cause of cancer death in men under 50 and the second leading cause in women of the same age group.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Are the incidents of colorectal cancer spread evenly among genders and races?

- Can you discuss the non-modifiable risk factors of CRC?

- Why is thorough client education important in managing modifiable risk factors for CRC?

- Why is gathering a thorough personal and family medical history important in the screening and prevention of colorectal cancer?

Anatomy and Physiology of the Colon and Rectum

The colon and rectum are parts of the large intestine. The large intestines play a crucial role in the digestive system by absorbing water and electrolytes, and forming stool. Understanding the colon and rectum’s structure and function is crucial in understanding colon and rectal cancer.

Essentially, the digestive system is composed of the esophagus, stomach, and small and large intestines. The first 6 feet of the large intestine are called the large bowel or “colon.” The last 6 inches are the rectum and the anal canal.

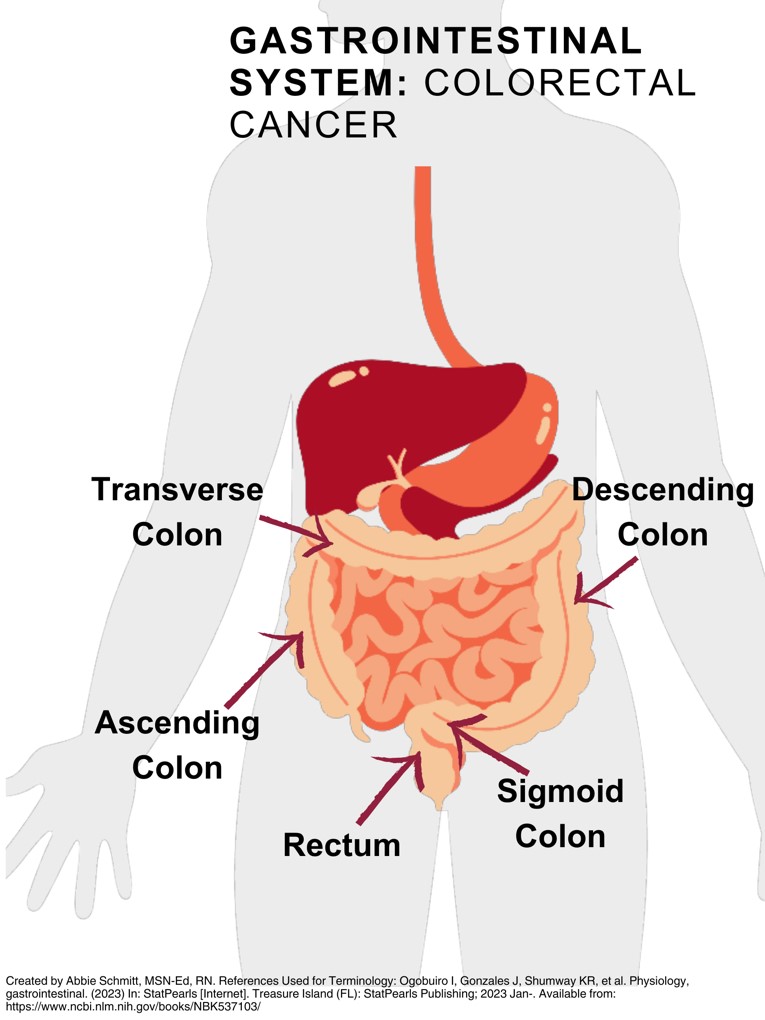

The colon is divided into four sections:

- Ascending Colon – Located on the right side of the abdomen, it extends upward from the cecum (where the small intestine meets the large intestine) and absorbs water and salts.

- Transverse Colon – Runs across the abdomen from right to left and continues the absorption process.

- Descending Colon – Travels down the left side of the abdomen and stores the remains of digested food that will be emptied into the rectum.

- Sigmoid Colon – S-shaped segment that connects the descending colon to the rectum and plays a key role in storing fecal material.

The inner wall of the colon contains smooth muscle that contracts to move contents through peristalsis. The rectum is the final part of the large intestine, approximately 12-15 cm long, and is located just above the anal canal. It stores feces until defecation.

Figure 2. Gastrointestinal System: Colon Cancer

Figure 2. Gastrointestinal System: Colon Cancer

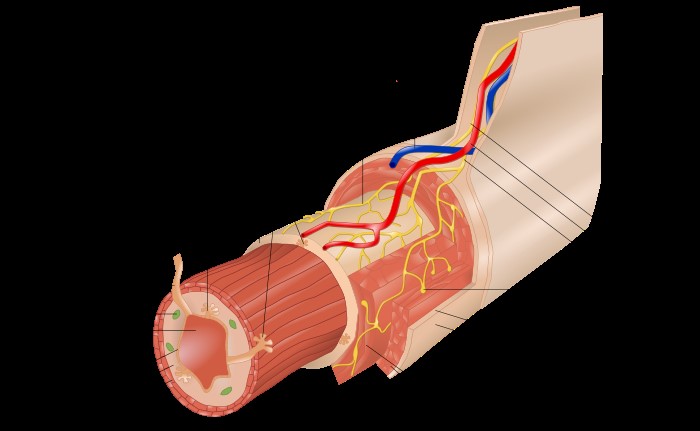

An understanding of the structure and layers of the wall of the intestines. This knowledge will be critical to understanding the staging of colon cancer in the next section.

The general histology has differences that reflect the specialization in functional anatomy; however, these walls of the intestines can be divided into four concentric layers in the following order:

- Mucosa

- Submucosa

- Muscular layer

- Serosa

The mucosa is the innermost layer and surrounds the lumen, or open space within the intestinal tube. The mucosa comes in direct contact with digested food, referred to as chyme.

The submucosa surrounds the mucosa and is made of dense, irregular connective tissue with large blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves branching into the mucosa and muscularis externa (. It also contains the submucosal plexus, which is an enteric nervous plexus, situated on the inner portion of the muscularis externa.

The muscular layer (muscularis) consists of an inner circular layer and a longitudinal outer layer. Between the circular and longitudinal muscle layers is the myenteric plexus, which controls peristalsis. Essentially, the contractions of these layers are called peristalsis and propel the food through the gastrointestinal tract.

The serosa is the outermost layer of the intestinal wall and consists of several layers of connective tissue. It is a thin, smooth membrane that forms part of the peritoneum, the lining of the abdominal cavity. The serosa covers the outside of the intestines and serves several important functions, including protection from injury, secretion of serous fluids to allow movement, and anchoring to the exterior abdominal region. The smooth surface of the serosa prevents the intestines from adhesion to each other in the abdominal cavity (15).

Nutrient waste travels along the colon and is moved to the rectum, the terminal end of the colon, where stool is stored. When stool is stored here, it causes a feeling of a need for defecation. Waste materials may progress quickly or very slowly through the intestines. Stress, medications, pregnancy, disease, lack of physical activity, and a diet poor in fiber and liquid impede normal functions of the intestine (15).

Figure 3. Anatomy of the colon wall (7)

Figure 3. Anatomy of the colon wall (7)

Remember these layers when we discuss colorectal cancer staging!

Physiological Roles of Colon and Rectum:

- Absorption – The colon absorbs water, electrolytes, and vitamins produced by gut bacteria (e.g., Vitamin K and some B vitamins).

- Forms stool – As material moves through the colon, water is absorbed, and the material is compacted into stool.

- Bacterial Fermentation – The colon houses trillions of bacteria that help break down undigested carbohydrates through fermentation, producing gas and short-chain fatty acids important for colon health.

- Storage and Elimination – The rectum stores feces until a voluntary decision to eliminate it is made. Stretching of the rectum triggers the urge to defecate.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are the major functions of the colon and rectum?

- What are the four sections of the colon?

- Can you identify and describe the location of the different segments of the colon?

- Do you think the location of cancerous cells within the colon would guide treatment options? Why or why not?

Colon Cancer Stages and Types

The cancer stage describes the extent of cancer in the colon and body, such as the size of the tumor, whether it has spread, and how far it has spread from where it first originated. It is important to determine the stage of colon cancer to carefully plan the appropriate treatment and provide education to the client on their disease and options.

The TNM staging system, developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), is the most commonly used staging tool for colorectal cancer.

This system is based on the following three key factors:

- T (Tumor): Describes the size and extent of the primary tumor, including how deeply the tumor has invaded the layers of the colon or rectum.

- N (Nodes): Indicates whether cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes.

- M (Metastasis): Describes whether the cancer has spread to distant organs or tissues (such as the liver or lungs).

These factors (T, N, and M) help determine and classify colorectal cancer into Stages 0 through IV. Higher numbers indicate more advanced disease.

The following stages are used for colon cancer:

- Stage 0

- Stage I Colon Cancer

- Stage II (also called stage 2) colon cancer

- Stage III (also called stage 3) colon cancer

- Stage IV (also called stage 4) colon cancer

AJCC Stage |

Stage Grouping |

Stage Description |

| 0 |

Tis N0 M0 |

|

| I |

T1 or T2 N0 M0 |

|

| IIA |

T3 N0 M0 |

|

| IIB |

T4a N0 M0 |

|

| IIC |

T4b N0 M0 |

|

|

IIIA

|

T1 or T2 N1/N1c M0 |

|

| OR | ||

|

T1 N2a M0 |

|

|

|

IIIB

|

T3 or T4a N1/N1c M0 |

|

| OR | ||

|

T2 or T3 N2a M0 |

|

|

| OR | ||

|

T1 or T2 N2b M0 |

|

|

|

IIIC

|

T4a N2a M0 |

|

| OR | ||

|

T3 or T4a N2b M0 |

|

|

| OR | ||

|

T4b N1 or N2 M0 |

|

|

| IVA |

Any T Any N M1a |

|

| IVB |

Any T Any N M1b |

|

| IVC |

Any T Any N M1c |

|

|

Additional categories:

|

||

| Reference used to create table: (3) | ||

It is meaningful for nurses and clinicians to stay up to date on these staging guidelines, as cancer research and management in constantly evolving. The latest update from the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) on colon cancer staging is the 9th edition of the Cancer Staging System, which transitioned from a manual-based format to a version-based system. This version began development in 2021 and includes updated staging protocols and new guidelines for various cancer types, including colon and rectal cancer. The AJCC Cancer Staging System is essential for healthcare providers to classify and stage cancer, ensuring standardized care. (3)

Colon Cancer Types

Colorectal cancer is classified based on the type of cells in which it originates.

Adenocarcinoma is the most common type of colon cancer; roughly 95% of colorectal cancers are adenocarcinomas. These cancers start in the glandular cells that line the inside of the colon and rectum and produce mucous.

Less common types of cancerous tumors include Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (GIST), carcinoid tumors, lymphomas, and sarcomas. GISTs begin in nervous tissue cells in the wall of the gastrointestinal tract; these are found more often in the stomach and small intestine and are not commonly found in the colon or rectum. Carcinoid tumors originate from cells that produce hormones and have neuroendocrine properties within the colon. Lymphomas originate in cells within the immune system and are primarily found in lymph nodes, but can also be found in the colon. Sarcomas begin in blood vessels, muscle tissue, or other connective tissue and rarely occurs in the colon.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is the most common type of colon cancer?

- How would cancerous tissue that has grown through the muscularis mucosa into the submucosa (T1) of the colon, but has not spread to lymph nodes or to distant sites be classified using AJCC staging system?

- What do the T, N, and M stand for in the TNM staging system for colon cancer?

- Which organization (mentioned in the text above) developed guidelines for describing and staging colorectal cancer?

Screening Guidelines

Gastroenterologists primarily rely on guidelines from evidence-based practice sources such as the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) for colorectal cancer screening guidelines. The guidelines from each entity have slight differences but overall parallel recommendations. The organizations provide evidence-based recommendations for screening based on individual risk factors, age, and family history.

The preferred method of screening by gastroenterologists is often a colonoscopy due to its dual role in diagnosing and removing precancerous polyps. The ACG specifically recommends colonoscopy every 10 years as the gold standard for average-risk individuals starting at age 45.

Guidelines generally emphasize early detection to reduce mortality from colorectal cancer.

Here are the key guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF):

- Start Screening: Age 45 to 75 for people at average risk.

- Age 76 to 85: Screening is considered on an individual basis, considering the client’s overall health and prior screening history.

- Age 85+: Screening is not recommended.

- A colonoscopy every 10 years is the gold standard, but other options like stool tests (annual FIT or sDNA-FIT) and imaging tests (CT colonography) are also available.

- There are now alternative options, such as FIT every year or CT colonography every 5 years, for those who decline or cannot have a colonoscopy.

(3, 17)

The American College of Physicians (ACP) updated its standing guidance statement for colorectal cancer screening in asymptomatic average-risk adults to assist clinicians with implementing evidence-based client care in 2024 as emerging methods of screening are integrated into care (9). The ACP emphasized the importance of discussing benefits, harms, costs, availability, frequency, and client values/preferences with clients before choosing a screening method. Risk factors are also essential in determining appropriate screening protocols and methods for each client.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended the following intervals for colorectal cancer screening tests: (17)

- High-sensitivity gFOBT or FIT every year

- sDNA-FIT every 1 to 3 years

- CT colonography every 5 years

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy every 10 years + FIT every year

- Colonoscopy screening every 10 years

Screening Methods and Tools

There are several options for colorectal cancer screening, including visualization methods, stool-based screening, and DNA testing.

Direct visualization methods include colonoscopy, CT colonography, and flexible sigmoidoscopy. All three screening tests apply visualization of the inside of the colon and rectum, although flexible sigmoidoscopy can only visualize the rectum, sigmoid colon, and descending colon, while colonoscopy and CT colonography visualize the entire colon (17). For colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy, a camera is used to visualize the inside of the colon, while CT colonography uses radiology imaging. Colonoscopy is recommended every 10 years, and CT colonography (virtual colonoscopy) is recommended every 5 years.

Stool-based screening tests include a highly sensitive fecal immunochemical test (FIT) or highly sensitive guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) and are recommended to be performed every year. Multi-targeted stool DNA testing (MT-sDNA) is a newer, non-invasive option that combines DNA and blood testing and is recommended every 3 years (6).

Individuals with a Higher Risk for Colon Cancer

Those with a family history of colon cancer are recommended to have earlier and more frequent screenings compared to those at average risk.

Here are key recommendations from substantial sources:

- American Cancer Society (ACS) and American College of Gastroenterology (ACG): (1)

- For those with a first-degree relative (parent, sibling, or child) with colorectal cancer or adenomatous polyps diagnosed before age 60, screening should begin at age 40 or 10 years earlier than the age at which the youngest affected relative was diagnosed, whichever is earlier.

- Screening should be done every 5 years, typically with a colonoscopy.

- ACG recommends starting at age 40 or 10 years younger than the youngest relative with colon cancer.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF): (17)

- The specific guidelines mirror those from ACS and ACG, focusing on starting 10 years earlier than the earliest diagnosis in the first-degree relative.

Colonoscopy is the preferred method for individuals with a family history due to its ability to both detect and remove polyps (1, 2, US, 6)

Colonoscopy

A colonoscopy examines the colonic mucosa using flexible instruments with light and camera features (6). This procedure is used for the diagnosis and treatment of all colonic segments from the anus to the cecum. Complications from the procedure are rare when it is performed by an experienced specialist or team and with proper equipment. Colonoscopy devices and imaging quality have improved over time and the procedure can be performed in endoscopy offices.

It is helpful to briefly review the anatomy of the colon again to recognize the scope of the procedure.

The colon starts at the right iliac fossa at the end of the small intestine, and this part of the colon is called the cecum. It continues from the cecum to the liver region and is called the ascending colon, then moves right to the spleen and takes the name of the transverse colon. The colon descends to the sigmoid colon and is called the descending colon. The descending colon is followed by the sigmoid colon, rectum, anal canal, and the anus (6).

In the colonoscopy examination, only the inner surface of the colon can be seen and evaluated. A colonoscopy cannot obtain information about the lesions within the colon wall, but the lesion can be found if it extends into the colon wall and causes a protrusion of the colon mucosa (6).

During the colonoscopy, the characteristics of the mucosal lesion can be identified with colonoscopy, but the depth of layers of the colon wall that are involved cannot be identified with the colonoscopy examination. Staging would require imaging methods such as endoscopic ultrasound, MRI, or computerized tomography (6).

Contraindications for Colonoscopy

Contraindications can be classified as absolute, meaning the procedure should not be performed, and relative contraindications, in which significant caution should be given.

Absolute contraindications include: (6)

- Intestinal perforation

- Acute peritonitis

- Intestinal obstruction

- Client’s refusal or inability to give consent to the procedure

- Toxic megacolon

- Fulminant colitis

Relative contraindications include: (6)

- Bleeding disorders

- Thrombocytopenia or neutropenia

- Platelet dysfunction

- Acute diverticulitis

- Previous bowel surgery

- Clients at risk of bowel perforation (Ehler-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome, etc.)

- Cardiac infarction history

- Pulmonary embolism

- Large abdominal aortic aneurysm

- Pregnancy (second or third trimester)

Guaiac-based Fecal Occult Blood Test (gFOBT) and Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT)

The guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) is a diagnostic method to assess for blood in the stool. Occult refers to hidden blood, and cancerous tissue can result in trace amounts of blood in the stool.

Immunochemical Tests (FIT) are now recommended over FOBT for colon cancer screening due to increased specificity, sensitivity, and decreased costs. High-sensitivity gFOBT is based on the chemical detection of blood, while FIT uses antibodies to detect blood (17).

FIT tests target human globin, which is often found with lower gastrointestinal bleeding, and it has been shown to improve detection rates for colorectal cancer compared to FOBT (11). Unlike the guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT, see below), there are no drug or dietary restrictions before the FIT test (because vitamins and foods do not affect the test) and collecting the samples may be easier. This test is also less likely to react to bleeding from the upper parts of the digestive tract, such as the stomach.

When stool-based tests reveal abnormal results, a follow-up colonoscopy for further evaluation is recommended.

sDNA-FIT

Stool DNA tests detect DNA biomarkers for cancer cells shed from the lining of the colon and rectum into stool. Colorectal cancer or polyp cells often have DNA mutations in certain genes, so these tests target these mutated cells. Multitargeted stool DNA test with fecal immunochemical testing (MT-sDNA or FIT-DNA or sDNA-FIT) looks for certain abnormal sections of DNA from cancer or polyp cells and also for occult blood. Currently, the only stool DNA test approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) combines a stool DNA test that also includes a FIT test, referred to as sDNA-FIT (17), or Cologuard, and tests for both DNA changes and blood in the stool (FIT).

This test is recommended to be done every 3 years.

Sigmoidoscopy

A sigmoidoscopy is similar to a colonoscopy except it doesn’t examine the entire colon. A sigmoidoscope, which is a flexible, lighted tube with a small video camera is put in through the anus, into the rectum, and then moved into the lower part of the colon. The sigmoidoscope only extends about 2 feet (60cm) long, so the doctor can only see the entire rectum and less than half of the colon.

This test is not widely used as a screening tool for colorectal cancer in the United States because a large portion of colon cancers begin before the sigmoid colon.

Computed tomographic (CT) Colonography

Computed tomographic (CT) colonography (or virtual colonoscopy) uses conventional CT scan techniques to generate images that allow the operator to evaluate a cleansed colon in any chosen direction (13). The procedure involves placing air to expand the colon or rectum to allow better visualization.

CT colonography is an option for CRC screening in asymptomatic average-risk individuals, but the role of CT colonography in screening for CRC is controversial. There is consensus that CT colonography should not be used for screening in clients at increased risk for CRC (eg, history of adenomas, inflammatory bowel disease, familial CRC syndrome), but guidelines differ in their recommendations for CT colonography in average-risk individuals.

In clients with colorectal cancer in whom a complete colonoscopy cannot be performed due to the inability to pass the colonoscope beyond an obstructing tumor, a CT colonography can be used for further evaluation. (13)

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is the most preferred method of stool testing for screening, FOBT or FIT?

- What are the screening recommendations for those with a first-degree relative with a diagnosis of colorectal cancer before the age of 60?

- Why is colonoscopy preferred over sigmoidoscopy for screening for CRC?

- Can you discuss the absolute and relative contraindications for colonoscopy procedures?

Barriers to Screening and Early Detection

There are several barriers to colon cancer screening that people face, but with the right strategies, healthcare providers can help overcome these obstacles.

Here are common barriers and possible solutions:

The barrier of a lack of healthcare access and/or insufficient insurance coverage. This challenge is dire and far-reaching. The inability to pay medical bills can lead people to skip necessary care for themselves and their families, including preventive screenings. There are currently initiatives within the healthcare and political levels to services to uninsured or underinsured clients, but the problem is leading to severe health disparities and the loss of life.

Advocacy and resources for those without insurance or sufficient insurance:

- The National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable (NCCRT), co-founded by the American Cancer Society, works to increase colorectal cancer screening rates. They offer information on low-cost and free screening programs, including for uninsured individuals.

- Website: https://nccrt.org/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) – Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP) partners with state health departments and clinics to provide low-cost or free colorectal cancer screening to eligible adults, particularly those who are uninsured or underinsured.

- The American Cancer Society (ACS) provides information on low-cost or free screening programs across the U.S.

- Website: https://www.cancer.org/

- There are local Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) that provide preventive healthcare services on a sliding fee scale based on income.

- Many FQHCs offer cancer screening services, including colonoscopies, at reduced costs or for free to uninsured clients.

- Clients can find a nearby FQHC by visiting the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) website.

- Website: https://findahealthcenter.hrsa.gov/

- Caseworkers, state health departments, and local community health centers have valuable information about available programs.

- Some hospitals, clinics, or cancer centers hold free screening events, especially during Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month (March).

Encouraging clients to reach out to these programs can improve access to life-saving colorectal cancer screenings by reducing financial burdens.

The barrier of transportation and work-related barriers. The American College of Physicians cites transportation and work-related concerns as a key limit on clients’ ability to access preventive care and recommended procedures (18). Specific obstacles include an inability to travel to the facility or take the required time off. Although telemedicine can help alleviate many circumstances, colon cancer screening methods often require in-person visits, especially colonoscopies. Some health systems have also developed shuttle systems and after-hours services to expand access so nurses can provide information on these services to clients facing this barrier. Healthcare policy addresses these types of barriers as well, calling for strict employer requirements for preventative care.

Client language barriers. Involving professional medical interpretation services and using multilingual client education to better support clients who have language barriers. Some cultural groups may have different attitudes toward medical procedures. It is important to use culturally sensitive materials and language-specific resources to communicate the importance of screening.

The barrier of fear and anxiety. Many individuals feel anxious about the potential diagnosis of cancer associated with colonoscopies or other screening tests. Fear of the preparation or procedure itself can prevent clients from pursuing screening. Nurses can educate clients on the minimal risks and discomforts of the procedure and offer non-invasive alternatives, such as the Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) or stool DNA tests.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Are you aware of additional barriers to preventative care and procedures?

- What are some ways that nurses can connect clients with resources on financial assistance?

- Can you discuss the disparities between those with and without insurance coverage and access to healthcare?

- Do you think that getting a colonoscopy would be a priority for an individual who is not able to pay for prescription medications or adequate housing?

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of colon cancer can vary depending on the stage and location of the tumor in the colon or rectum. Some clients may experience no symptoms in the early stages, making screening extremely crucial for early detection. However, common signs and symptoms include: (10)

- Abdominal pain or discomfort

- Clients may describe persistent cramping, bloating, or gas

- Sharp pains are common if the tumor obstructs the colon.

- Gastrointestinal bleeding

- Bright red or dark blood in the stool may indicate bleeding from a tumor in the colon or rectum.

- Blood might not always be visible and may be detected only through screening tests like a fecal occult blood test (FOBT).

- Changes in bowel habits

- Persistent diarrhea, constipation, or a change in stool consistency (narrower than usual stools) lasting more than a few days.

- A sensation that the bowel doesn’t completely empty after a bowel movement

- Changes in stool appearance and formation

- Abnormal fatigue and weakness

- Results from iron deficiency anemia related to blood loss

- Unexplained weight Loss

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) reports a substantial study that identified four warning signs that can potentially catch the disease at an earlier and more treatable stage. The research study analyzed data on more than 5,000 people diagnosed with early-onset colorectal cancer (before the age of 50), and more than 22,000 people without cancer (controls).

The analysis showed that, in the period of 3 months to 2 years before people with colorectal cancer were diagnosed, four signs were more commonly reported in people who developed colorectal cancer than among the controls:

- Abdominal Pain

- Rectal Bleeding

- Diarrhea

- Iron Deficiency Anemia

Having just one of these signs was associated with nearly twice the likelihood of being diagnosed with early-onset colorectal cancer and having three or more of these signs was associated with six times the likelihood of being diagnosed with colorectal cancer.

(14)

Laboratory Evaluation

Lab tests can help in the diagnosis, staging, and monitoring of colon cancer. The common lab results that can be associated with colon cancer:

- Fecal Occult Blood Test (FOBT):

- Complete Blood Count (CBC):

- A CBC can detect anemia.

- A low hemoglobin level, especially iron deficiency anemia, can be a sign of undetected colorectal cancer.

- Biopsy Results

- A biopsy taken during a colonoscopy is microscopically examined to confirm the presence of cancer cells. This is the definitive diagnostic test for colon cancer.

- Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA) Test

- Elevated CEA levels can indicate cancer but are not specific to colorectal cancer.

- Liver Function Tests:

- Elevated levels of liver enzymes such as ALT and AST may suggest liver involvement.

These lab results, in combination with imaging studies like CT scans, help guide the diagnosis, staging, and treatment of colon cancer.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you describe common signs and symptoms of colorectal cancer?

- What questions and assessments should be done if clients report rectal bleeding?

- How can nurses educate clients on early-onset colorectal cancer detection?

- Why is it so critical to evaluate changes in bowel patterns or unexplained weight loss?

Treatment Options

The treatments for colorectal cancer depend on the stage of the cancer, the location of the tumor, comorbidities, and the overall health status of the client. The primary treatments include surgical procedures to remove cancerous tissue, targeted treatment, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy, and palliative care.

Significant research trials exploring the best sequence of treatments, together with the integration of novel drugs, are ongoing. It is meaningful to continuously follow updates and evidence-based practice guidelines.

Surgery is the most common treatment for all stages of colon cancer (14).

- Polypectomy: This procedure is the removal of the concerning polyp and is often removed during a colonoscopy.

- Local excision: In the early stages, the surgeon may remove cancerous tissue without cutting through the abdominal wall.

- Resection of the colon with anastomosis: Based on the individualized factors, surgeons can perform a partial colectomy (removing the cancerous tissue and a small amount of healthy tissue around it). An anastomosis, or resection, would be performed afterward.

- Resection of the colon with colostomy: If the connection of the two ends of the colon is not possible following removal of the cancerous tissue, a stoma is created where stool is directed out of the abdominal cavity and collected externally. This procedure is called a colostomy.

Radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy is often administered before and/or after surgery.

Targeted therapy uses drugs or other substances to identify and attack specific genes or proteins that contribute to cancer growth (14). Targeted therapy is often used in combination with chemotherapy for advanced stages of colon cancer (Stage IV).

Immunotherapy helps boost the body’s immune system to fight cancer cells. It is particularly used in cases of microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR) colon cancers.

Palliative care is an essential part of treatment in advanced-stage colon cancer because relieving symptoms is imperative. Palliative care involves managing pain, bowel obstruction, or bleeding. Palliative care also integrates curative treatments. Sometimes there is confusion and misunderstandings about palliative care in that remission is no longer possible, but this is not the case.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How do the size, location, and stage of cancerous tissue guide treatment?

- What treatment options are available for clients with advanced-stage colon cancer?

- Why is it imperative to provide education and support while involving the client in their treatment plan?

- How would you explain palliative care services to clients and their families?

Role of the Nurse in Colon Cancer Screening

Nurses have broad and meaningful roles in colon cancer screening. Nurses are essential in improving colorectal cancer screening rates and outcomes by providing education, advocacy, and coordination.

Client Education. Nurses educate clients on the importance of early detection and the various screening options, such as colonoscopy, fecal occult blood test (FOBT), fecal immunochemical test (FIT), and DNA stool testing. Nurses provide critical education on the benefits of screening, how the procedures are performed, and what clients can expect.

Sometimes, clients can be hesitant or unaware of the need for screening, so nurses play a critical role in providing culturally sensitive information and addressing any misconceptions.

Risk Assessment. Nurses help assess a client’s risk for colorectal cancer by gathering family and personal medical history, as well as evaluating lifestyle factors like diet, smoking, and physical activity. This information helps determine when screening should begin, particularly for individuals at higher risk (e.g., those with a family history of colorectal cancer).

Screening Test and Procedure Coordination. Nurses are often responsible for coordinating and scheduling colonoscopies or other screening tests. This includes providing and explaining necessary pre-procedure instructions, such as bowel prep for colonoscopy, and that they understand dietary or medication restrictions. They also assist in following up on screening results, ensuring that clients with abnormal findings receive appropriate referrals and follow-up care, such as biopsies or additional imaging.

Role During Colonoscopy. Nurses play a critical role during the colonoscopy by ensuring client safety, comfort, and the smooth operation of the procedure.

Key responsibilities include (16):

- Client Preparation

- Nurses conduct thorough client assessments and verify the client’s medical history, medication use, and allergies to prevent complications.

- Nurses ensure that the client has completed the required bowel preparation and adhered to dietary restrictions before the colonoscopy.

- IV placement

- Nurses are responsible for establishing an intravenous (IV) line if required.

- Monitoring During the Procedure:

- Nurses continuously monitor the client’s vital signs, including their heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen levels, and respiratory status, to detect any signs of distress or adverse reactions to sedation or anesthesia.

- Assisting the Gastroenterologist

- Nurses assist the gastroenterologist by handling instruments, operating the suction, adjusting client positioning, or using tools to improve the visibility of the colon.

- They also assist with biopsies or polyp removal that may occur during the procedure. Proper collection and handling is important.

- Ensuring Client Safety

- Nurses ensure that the client’s airway remains open and that the client is stable throughout the procedure, particularly when sedation is used. They are vigilant in recognizing and responding to any signs of complications, such as a drop in oxygen levels or abnormal vital signs.

- Documentation

- Accurate documentation of the procedure is essential, including the client’s pre- and post-procedure status, medications administered, and any complications that arise during the procedure.

Post-Procedure Care. Following a colonoscopy or other screening procedure, nurses are involved in providing post-procedure care. This includes monitoring for complications such as bleeding, obstruction, and abdominal pain, and offering recovery instructions.

Community Outreach. There are many opportunities for nurses to engage in community health initiatives to promote colorectal cancer screening, especially during awareness campaigns like Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month. Nurses can participate in education sessions, screenings, or health fairs aimed at increasing screening rates in the general population and their community.

Level of Prevention |

Nursing Role |

| Primary Prevention |

|

| Secondary Prevention |

|

| Tertiary Prevention |

|

Table 1. Colon Cancer Level of Prevention and Nursing Roles (8)

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How can nurses who do not directly work in gastroenterology provide meaningful advocacy to clients on colon cancer prevention?

- Why is collaboration among interdisciplinary healthcare team members essential in the prevention of colon cancer?

- Can you name the specific roles of nurses during colonoscopy procedures?

- Why is it important for nurses to recognize the risk factors of colorectal cancer?

Resources

- American College of Gastroenterology (ACG)

- ACG provides screening guidelines that are particularly helpful for gastroenterologists and clinicians managing high-risk clients.

- Website: https://gi.org/topics/colorectal-cancer/

- The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)

- The USPSTF is a leading source of evidence-based recommendations on colorectal cancer prevention. They offer guidelines for screening individuals at average risk and special recommendations for high-risk populations.

- Website: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/colorectal-cancer-screening

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)

- The NCCN provides evidence-based practice guidelines on colorectal cancer screening, diagnosis, and management.

- These guidelines are widely used by oncologists and other healthcare providers.

- Website: https://www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/content/PDF/colorectal-screening-patient.pdf

- American Cancer Society (ACS)

- The ACS offers detailed guidelines on colorectal cancer screening for both average-risk and high-risk individuals.

- The guidelines cover different screening methods, recommended starting ages, and screening intervals in client-friendly formats.

- https://www.cancer.org/

These resources provide evidence-based guidelines and are updated regularly to reflect new research in colon cancer prevention and treatment.

Research

Cell-Free DNA (cfDNA) Blood Test

A cfDNA blood test was developed to identify aberrant DNA-methylation status, abnormal DNA-fragmentation patterns, and the presence or absence of somatic pathogenic variants in certain genes. In the ECLIPSE trial, researchers conducted a study at primary care sites and endoscopy centers across the United States; overall, the study results demonstrated the feasibility of using plasma cfDNA to screen for colorectal cancer but showed relatively low sensitivity for detecting advanced precancerous lesions. Currently, the cfDNA blood-based test is still awaiting approval by the FDA and is not covered by Medicare. (4)

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Why do you think it is important to develop less invasive, but highly effective methods of colon cancer screening?

- Are you familiar with the cfDNA and do you anticipate it being highly used in the medical community?

Case Study: The Tale of Two Colorectal Cancer Paths

Have you ever read a book or watched a movie in which the character explores how actions lead to different outcomes? Somehow this character finds a time machine or phenomenon that allows them to travel back in time and change a certain decision.

In this case study, learners will have the opportunity to push the “REWIND” button and possibly alter the outcomes for a client, John.

John: Pathway #1

John is a 50-year-old male with no significant medical history who visits his primary care physician for a routine check-up. John is a truck driver and needs a physical form completed for his license. John admits to the nurse that he “does not like coming to the doctor”. John denies taking any medication and has no complaints today. His vital signs are within normal limits. His provider explains preventative screening measures, including a referral to a gastroenterologist for routine screening based on his age. John explains he is very busy with long-distance jobs at the moment but will tell his wife to remind him. There is no education provided on the value of early detection, the possible outcomes, or an evaluation of his family history. The nurse and provider assume John knows the risks of colon cancer.

- Why would it be important to collect a family history during John’s visit?

- Can you think of different ways primary care providers can follow up on referrals?

- If a client refuses a colonoscopy, are there other measures, or is it recommended to not screen those clients at all?

- Other than verbally educating John on the importance of screening, what other methods of teaching would be helpful?

Eight years passed by, and that visit and the brief recommendation for colon cancer screening were forgotten. John did not return calls from the gastroenterology office and did not have the colonoscopy.

John is now 58 years old, has two grandchildren, and is looking forward to retirement soon. He visits his primary care for another routine physical. John has been relatively healthy, but he admits to having experienced occasional abdominal pain and changes in bowel habits (including intermittent diarrhea and occasional blood in his stool) over the past six months. He attributes this to stress and a poor diet of processed food that he eats at fast food restaurants. He also remembered a detail about his family history – his dad passed away from lung cancer, but he remembers the doctor mentioned it initially started in his large intestine. His father was initially diagnosed at age 56.

He agrees to a colonoscopy that is strongly recommended by his provider at this time.

The colonoscopy reveals a large tumor in the colon, and a biopsy and other imaging confirm the diagnosis of Stage III colorectal cancer. The cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes, making treatment more complex. John has surgery to remove the tumor, followed by several rounds of chemotherapy and radiation therapy to target the remaining cancer cells. His recovery is difficult, with side effects from the treatments significantly impacting his quality of life. He is unable to work and has additional financial strains.

While the treatment manages to stop the progression of the cancer, John’s outlook is more uncertain due to the advanced stage at which the cancer was detected. He faces a higher risk of recurrence and requires ongoing monitoring, additional treatment, and more frequent medical visits. His life expectancy and quality of life are significantly diminished compared to if the cancer had been caught earlier.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Based on the information known now, at what age would it be recommended that John have initial colon cancer screening performed?

- Can you discuss the various ways cancer diagnosis, surgery, and other treatments can impact the quality of life (financial, work-life balance, etc.)?

- How should the nurse provide education on screening recommendations for John’s biological children?

- What other risk factors was John facing?

John: Pathway #2

The nurse noted John’s family history of “lung cancer” under paternal family history and decided to gain a more thorough family history. John said, “The colon cancer spread to my father’s lungs”. This information is relayed to the provider. The nurse knows that education on risk factors and recommendations is appropriate.

Here are some strategies this nurse and others can use in providing advocacy on colon cancer screening:

- Explain that colon cancer is highly treatable when caught early and that screening can detect cancer before symptoms appear.

- Discuss risk factors, including age, family history, or personal risk factors such as smoking or poor diets.

- Address barriers and misconceptions. Ask what questions they have or worries about the preparation and/or the

- Discuss the availability of at-home screening tests, like FIT or stool DNA tests, for clients who are hesitant about invasive procedures. These tests can often be done in the privacy of their home.

- Reassure the client that the procedure is routine and that many people find the experience more comfortable than they initially expected. Be prepared to offer additional resources, such as client testimonials or information sessions, to ease their concerns.

- If appropriate, encourage the client to discuss screening with family members. Family support can sometimes motivate clients to act, especially if colorectal cancer runs in the family.

- Arrange follow-up appointments or calls to check in if the client is still unsure about the screening.

After discussing his concerns with his physician and learning about the risks of colorectal cancer, John agrees to undergo a colonoscopy. During the procedure, the gastroenterologist finds a small polyp in his colon. A biopsy is performed, and the polyp is confirmed to be adenocarcinoma. However, the cancer is still in its early stage (Stage I) and has not spread to nearby tissues or lymph nodes.

During the colonoscopy, the cancerous polyp was completely removed. Since the cancer was detected early, no further treatment (such as chemotherapy or radiation) is required. His physician recommends regular follow-up colonoscopies every 3-5 years to ensure no recurrence and yearly stool testing.

Thanks to early detection, John’s cancer is completely removed, and he makes a full recovery. His risk of cancer returning is low, and he remains healthy, continuing with routine screenings as recommended by his doctor.

This case highlights the critical importance of early colorectal cancer screening. In the first scenario, John’s decision to undergo screening allowed for early detection, simple treatment, and full recovery. In contrast, in the second scenario, delaying screening resulted in a much more serious diagnosis, requiring aggressive treatment with more significant risks and impacts on his long-term health. Early screening for colorectal cancer saves lives by catching the disease at a more treatable stage.

- Have you ever cared for a client with colon cancer that was “caught late”?

- How did the nurse advocate for John in the second pathway?

- How would you describe the difference between providing guidance in an assertive, supportive way vs. a domineering way?

- Do you believe that nurses have the chance to save lives?

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some barriers faced by clients in colon cancer screening and preventative care?

- Can you explain the TNM staging system in staging colon cancer?

- What are the key roles of nurses in colon cancer screening and prevention?

- What are some resources for clients who face financial barriers and a lack of insurance?

- What are the various types of colon cancer screening methods?

- Can you name the risk factors associated with colorectal cancer?

- Why is it important to understand the anatomy and physiology of the gastrointestinal tract when exploring colon cancer?

- Which organizations and entities have provided evidence-based guidelines on colon cancer screening?

- Do you recognize any gaps in practice relating to colon cancer screening and clinical diagnosis?

- Do you feel confident in providing education on the importance of colon cancer screening?

Conclusion

As we conclude this course on colon cancer screening and clinical diagnosis, it is important to remember that healthcare professionals are at the frontline of saving lives through early detection and prevention.

Remember, screening is more than just a medical procedure—it’s an opportunity to prevent cancer, reduce suffering, and extend lives. By making screening accessible, addressing client concerns with empathy, and promoting adherence to guidelines, you contribute to the broader fight against colon cancer.

References + Disclaimer

- American Cancer Society. (2024a). Cancer facts & figures 2024. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2024/2024-cancer-facts-and-figures-acs.pdf

- American Cancer Society. (2024b). Colorectal cancer treatment guidelines. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/treating.html

- American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). (2021). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (9th ed.). Springer.

- Chung DC, Gray DM, Singh H, et al.: A Cell-free DNA Blood-Based Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. N Engl J Med 390 (11): 973-983, 2024.

- Dariya, B., Chalikonda, G., Nagaraju, G.P. (2021). Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer. In: Nagaraju, G.P., Shukla, D., Vishvakarma, N.K. (eds) Colon Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63369-1_1

- Engin, O., Kilinc, G., Sunamak, O. (2021). Colonoscopy. In: Engin, O. (eds) Colon Polyps and Colorectal Cancer. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57273-0_3

- Goran tek-en, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

- Hashemi, N., Bahrami, M., Tabesh, E., & Arbon, P. (2022). Nurse’s Roles in Colorectal Cancer Prevention: A Narrative Review. Journal of Prevention, 43(6), 759-782. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-022-00694-z

- Hawk, E.T., & Stephanie L. Martch, S.L. (2024). Recent American College of Physicians Guidance Statement for Screening Average-risk, Asymptomatic Adults for Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 1 January 2024; 17 (1): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-23-0383

- Holtedahl, K., Borgquist, L., Donker, G.A., Buntinx, F., Weller, D., Campbell, C., Månsson, J., Hammersley, V., Braaten, T., Parajuli, R. Symptoms and signs of colorectal cancer, with differences between proximal and distal colon cancer: a prospective cohort study of diagnostic accuracy in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2021 Jul 8;22(1):148. doi: 10.1186/s12875-021-01452-6. PMID: 34238248; PMCID: PMC8268573.

- Kaur, K., Zubair, M., & Adamski, J.J. Fecal Occult Blood Test. [Updated 2023 Apr 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537138/

- Nagaraju, G. P., Shukla, D., & Vishvakarma, N. K. (Eds.). (2021). Colon cancer diagnosis and therapy. Volume 1. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63369-1

- Nagata, N., & Liddell, R. M. (2024). Overview of computed tomographic colonography. UpToDate. Retrieved October 2, 2024, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-computed-tomographic-colonography

- National Cancer Institute. (2022). Cancer stat facts: Colorectal cancer. SEER. Retrieved October 21, 2024, from https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html

- Salimoglu, S., Kilinc, G., Calik, B. (2021). Anatomy of the Colon, Rectum, and Anus. In: Engin, O. (eds) Colon Polyps and Colorectal Cancer. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57273-0_1

- Thiesen, K. M., & Guzman, S. J. (2020). Nursing care during gastrointestinal endoscopy procedures. Gastroenterology Nursing, 43(2), 115-121.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2021). Colorectal cancer: Screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/colorectal-cancer-screening

- Wolfe, M.K., McDonald, N.C., Holmes, G.M. (2020). Transportation barriers to health care in the united states: findings from the national health interview survey, 1997-2017. Am J Public Health. 2020 Jun;110(6):815-822. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305579. Epub 2020 Apr 16. PMID: 32298170; PMCID: PMC7204444.

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate