Course

Connecticut APRN Bundle Part 1

Course Highlights

In this course we will cover a variety of nursing topics pertinent in the state of Connecticut. This course is appropriate for APRNs. Upon completion of this single module you will receive a certificate for 20 contact hours.

About

Contact Hours Awarded:

Course By:

Various Authors

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

Cultural Competence in Nursing

Introduction

There is no doubt that modern medicine has made many technological advancements over the last few decades, forging the way for highly intricate diagnostic and treatment methods and improving the quality and longevity of many lives. To keep up with changing times, however, healthcare professionals must consider much more than the technical aspects of healthcare delivery.

They must take a closer look and a more conscientious approach to delivering care, particularly across various demographics and characteristics. Ensuring care is delivered with empathy, respect, and equity, noting and honoring a patient's differences, is how care transforms from good to great. Practicing diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and cultural competence in nursing must become a standard.

Health Disparities

When covering cultural competence in nursing, a provider must know that each patient is unique. However, some characteristics such as race, gender, age, sexual orientation, or disability can create gaps in the availability, distribution, and quality of healthcare delivered.

These gaps can create lasting negative impacts on patients mentally, physically, spiritually, and emotionally and even lead to poorer outcomes than patients not within a particular population. Modern healthcare professionals are responsible for learning to identify risks, provide sensitive and inclusive care, and advocate for equity in much the same way that they are responsible for understanding how the human body, medications, or hospital equipment works.

Epidemiology

Let's turn to data to understand the importance of cultural competence in nursing and the best practices for DEI in healthcare.

Healthy People 2020 provides a myriad of data that includes countless implications for changes needed in healthcare settings for equitable care of all populations. The data includes statistics such as:

- 12.6% of Black/African American children have a diagnosis of asthma, compared to 7.7% of white children (11).

- The rate of depression in women ages 65+ is 5% higher than that of men of the same age across all races (11).

- Teenagers and young adults who are part of the LGBTQ community are 4.5 times more likely to attempt suicide than straight, cis-gender peers (11).

- 16.1% of Hispanics report not having health insurance, compared to 5.9% of white populations (11).

- The national average of infant deaths per 1,000 live births is 5.8. The rate for Black/African American infants is nearly double at 11 deaths per 1,000 births (11).

- 12.5% of veterans are homeless, compared to 6.5% of the general U.S. population (11).

Additional disparities are seemingly endless and unquestionably point to the fact that healthcare professionals cannot be uninformed about cultural competence and DEI awareness. This course aims to outline and explore the most common or severe healthcare disparities, address ways healthcare delivery needs to be adjusted, and start the conversations needed to create a new generation of healthcare professionals who will close these gaps.

Understanding DEI best practices in the health setting and possessing cultural competence in nursing is vital in making positive changes for all populations.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How do characteristics like race, gender, age, sexual orientation, or disability contribute to disparities in healthcare delivery, and why is it essential for providers to recognize these gaps?

- Why do you think programs like Healthy People gather statistics about specific demographics and gaps between populations?

- How has our collection of and attention to this type of data changed over the years, and how might that impact our historical knowledge about healthcare?

- Why must modern clinicians integrate cultural competence into their education, training, and general approach to patient care? How is this different from the delivery of healthcare in the past?

- What inequities have you witnessed or even experienced yourself regarding healthcare delivery?

Impact of Implicit Bias

Nurses must first understand implicit bias and how it impacts care delivery when working toward culturally competent care. Implicit bias is a subconscious attitude of opinion about an individual or a group that could influence the actions and decisions of the clinician. (It is important to note that this differs from explicit bias, which is a controllable attitude or action such as making sexist comments or using racial slurs.) (30)

Everyone has implicit biases; they are essentially our own unique lens through which we view the world, shaped by our upbringing and life experiences. What is important is that clinicians develop an awareness of that lens, recognize that their viewpoint is not objective, and understand ways that bias may be impacting their feelings, attitudes, or actions toward others (30).

Sometimes, implicit biases impact care in a positive way. If you care for a client who tells you they are retired from nursing, you may feel a connection or warmth towards them and go above and beyond the level of care required due to this positive connection.

In the context of cultural competence, however, we must consider how implicit bias might negatively impact care delivery. Common examples of the effects of implicit bias in healthcare include:

- Assuming elderly clients have cognitive or physical limitations

- Feeling female clients have too many complaints or are exaggerating

- Assuming sexually active clients are heterosexual

- Suspecting a chatty client asking for an ADHD evaluation is just lazy and wants medication to make things easier

- Assuming someone without a visible disability is able-bodied (30)

Over time, these negative connotations can create dissatisfied clients or more considerable repercussions like missed diagnoses, lack of clear communication, delayed treatment, and reduced quality of care and outcomes.

To deliver culturally competent care, individual clinicians and institutions must assess for and identify biases and the ways they have shaped healthcare. On a personal level, this can be done through self-reflection, attending training or workshops, and working or volunteering with populations that challenge one's biases or are different from one's own.

On an institutional level, clinics and hospitals should monitor client data and assess for gaps and trends in those gaps. They may also poll clients on satisfaction with care or suggestions for improvement and ensure that staff demonstrate compliance with implicit bias and cultural competence training (30).

There is much more to be explored with implicit bias. Still, for the scope of this course, it is essential to introduce the concept and for readers to keep this in mind while further exploring groups that experience the most health-related disparities.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Think about the difference between implicit and explicit bias. Why is this distinction important when delivering patient care?

- How might implicit bias influence the quality of care you deliver, even if it is a positive bias?

- Why do you think it is essential to recognize your thoughts and attitudes are not objective? How does this recognition affect cultural competence?

- Are there any systematic changes your healthcare facility could make to address implicit bias?

- What are some potential challenges to clinicians engaging in self-reflection about implicit biases?

Race & Ethnicity

One of the most significant disparities in healthcare, and the one garnering the most attention and campaigns for change in recent years, is race and ethnicity. However, when covering the best practices for cultural competence in nursing, we must go over this topic. Studies in recent years have revealed that minority groups, particularly Black Americans, are sicker and die younger than white Americans. Examples include:

Current data shows that Black men are more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer and 2.2 times more likely to die from it than their white peers. Black men are also diagnosed at a younger age, about two years earlier, yet less likely to be screened or treated aggressively than white men.

Lillard et al.(2022) explored the demographic, health literacy, and population trends impacting the differences in identifying and treating this condition. They found many contributing differences in the way Black men receive and engage with healthcare (16). Among the most impactful differences were cultural mistrust of the healthcare system, poor physician-patient communication, undereducation about prostate cancer within the Black community, and lack of access to care (both geographic and financial) for Black men (16).

A 2020 study found that Black individuals over age 56 experience a decline in memory, executive function, and global cognition at a rate much faster than their white peers, often as much as 4 years ahead in terms of cognitive decline. Data in this study attribute the difference to the cumulative effects of chronically high blood pressure, more likely to be experienced by Black Americans (14).

Black women experience twice the infant mortality rate and nearly four times the maternal mortality rate of non-Hispanic white women during childbirth. One in five Black and Hispanic women report poor treatment during pregnancy and childbirth by healthcare staff. Studies indicate that in addition to biases within the healthcare system, some of these poor outcomes may also be attributed to cumulative effects of lifelong inferior healthcare (15).

Lack of health insurance keeps many minority patients from seeking care at all. 25% of Hispanic people are uninsured and 14% of Black people, compared to just 8.5% of white people. This leads to a lack of preventative care and screenings, a lack of management of chronic conditions, delayed or no treatment for acute conditions, and later diagnosis and poorer outcomes of life-threatening conditions (2).

Emerging data indicates that hospitalizations and deaths from COVID-19 are disproportionately affecting Black and Hispanic Americans, with Black people being 153% more likely to be hospitalized and 105% to die from the disease than white people. Hispanic people are 51% more likely to be hospitalized and 15% more likely to die from COVID-19 than white people (18).

There are many potential reasons, from genetics to environmental factors such as socioeconomic status. However, data repeatedly shows that these factors are not enough to account for the disproportionate health outcomes; it eventually comes down to inequity in the structure of the healthcare systems in which we all live. For example:

Medical training and textbooks are mostly commonly centered around white patients, even though many rashes and conditions may look very different in patients with darker skin or different hair textures (9).

There is also a lack of diversity in physicians; in 2018, 56.2% were white, while only 5% were Black and 5.8% Hispanic. More often than not, patients will see a physician of a different race than they are, which can mean their particular experiences as a minority person and how that relates to their health are not well understood by their physician (1).

While the Affordable Care Act increased the number of people who have access to health insurance, minority patients are still disproportionately uninsured, which leads to delayed or no care when necessary (2).

Minority patients are also often those living in poverty, which goes hand in hand with crowded living conditions and food deserts due to outdated zoning laws created during times of segregation. This means less access to nutritious foods, fresh air, or clean water, which negatively affects health (18).

Potential solutions to these problems are in the works across many fronts, but the breakdown and resetting of old institutions will likely require change on a broader political level.

Medical school admission committees could adopt a more inclusive approach during the admission process. For example, they should pay more attention to the background and perspectives of their applicants and the circumstances/scenarios they came from as opposed to their involvement in extracurriculars (or lack thereof) and former education.

Incentivizing minority students to choose careers in healthcare and investing in their retention and success should become a priority in the admissions process (9). This is one of the main drivers and only possible paths to having minority representation in healthcare systems nationwide.

Properly training and integrating professionals like midwives and doulas into routine antenatal care and investing in practices like group visits and home births will give power back to minority women while still giving them safe choices during pregnancy (15).

Universal health insurance, basic housing regulations, access to grocery stores, and many other socio-political changes could also help close the gaps in accessibility to quality healthcare, which may vary by geographic location.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- When you have a medical appointment, how do you get there?

- How do you pay for the services?

- Do you have a provider that understands your unique needs?

- How might the answer to those questions vary for someone of a different race living in the same town?

- How might having a healthcare provider of the same race impact a client's healthcare experience?

LGBTQ+

Another highly at-risk group for healthcare inequity are members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transexual, and Queer (LGBTQ+) community. When practicing cultural competence in nursing, the provider must know that this population is vulnerable, especially in healthcare settings. Risks and examples of disparities within the LGBTQ+ community include:

- Youth are 2-3 times more likely to attempt suicide.

- More likely to be homeless.

- Women are less likely to get preventative screenings for cancer.

- Women are more likely to be overweight or obese.

- Men are more likely to contract HIV, particularly in communities of color.

- Highest rates of alcohol, tobacco, and drug usage

- Increased risk of victimization and violence

- Transgender individuals are at an increased risk for mental health disorders, substance abuse, and suicide and are more likely to be uninsured than any other LGBTQ+ individuals (12)

Current data suggests that most of the health disparities faced by this group of people are due to social stigma, discrimination, lack of access or referral to community programs, and implicit bias from providers, leading to missed screenings or care opportunities.

Support systems and social acceptance are strongly linked to the mental health and safety of these individuals. Lack of support and acceptance in the home, workplace, or school leads to adverse outcomes. Also, a lack of social programs to connect LBGTQ+ individuals and build a community of safety and acceptance creates further gaps.

There is currently still discrimination in access to health insurance and employment for this population, which can affect the accessibility of quality health care as well as affordable coverage.

Following this, a compilation of recent data showcases significant issues with the quality and delivery of care provided to those in the LGBTQ+ community. This data includes:

- A 2022 study of the healthcare experiences of LGBTQ+ individuals revealed

- 18% admit to avoiding medical care due to fear of discrimination over gender identity.

- 22% of transgender individuals have avoided healthcare for fear of discrimination

- 31% of transgender individuals did not have a primary healthcare provider at all (27)

- The same study found that, upon chart review of 1376 healthcare facilities and nearly 26 million patients, 77.1% did not have a sexual orientation or gender identity documented in the health record (2022).

- A 2023 nationwide survey found that 80.6% of endocrinologists and 82.5% of emergency providers reported never receiving any training about caring for transgender patients, despite 80% and 88%, respectively, reporting having transgender patients on their caseload (29).

- The same study revealed that 79% of nurses in the San Francisco area reported never receiving LGBTQ training despite regularly encountering LGBTQ+ patients in their work setting (29).

To improve these conditions and close the gap for LGBTQ+ individuals, much can be done on the community level and in medical training:

- Community programs should be available to create safe spaces for connection and acceptance.

- Laws and school policies can focus on how to prevent and react to bullying and violence against LGBTQ+ individuals.

- Cultural competence training in medical professions needs to include LGBTQ+ issues.

- Data collection regarding this population needs to increase and be recognized as a medical necessity, as it is currently largely ignored.

Providers must stay current on changes and health trends among LGBTQ+ populations, as healthcare delivery methods may require adjustments over time; this is critical when learning about cultural competence in nursing.

Understanding these risk factors is essential for healthcare professionals, and addressing implicit biases is necessary to help close gaps in care for this population. At the root of many of the biases regarding LGBTQ+ clients is a lack of understanding or cultural competence when caring for people in this community. Healthcare professionals need to familiarize themselves with the definitions and differences in sexuality, gender identity, and the many terms within those categories to have a better understanding of how these factors affect the health and safety of clients. The following list should provide a basic understanding and clarification for healthcare professionals working towards greater comfort in caring with this population:

- Sex: A label, typically of male or female, assigned at birth, based on the genitals or chromosomes of a person. Sometimes, the label is "intersex" when genitals or chromosomes do not fit into the typical categories of male and female. This is static throughout life, though surgery or medications can attempt to alter physical characteristics related to sex.

- Gender: Gender is more nuanced than sex and is related to socially constructed expectations about appearance, behavior, and characteristics based on gender. Gender identity is how a person feels about themselves internally and how this matches (or doesn't) the sex they were assigned at birth. Gender identity is not related to who a person finds physically or sexually attractive. Gender identity is on a spectrum and does not have to be purely feminine or masculine; it can also be fluid and change throughout a person's life.

- Cis-gender: When a person identifies with the sex they were assigned at birth and feels innately feminine or masculine.

- Transgender: When a person identifies with the opposite sex they were assigned at birth. This can lead to gender dysphoria or feeling distressed and uncomfortable when conforming to expected gender appearances, roles, or behaviors.

- Nonbinary: When a person does not feel innately or overwhelming feminine or masculine. A nonbinary person can identify with some aspects of both male and female genders or reject both entirely.

- Sexual orientation: A person's identity about who they are attracted to romantically, physically, and sexually. This can be fluid and change over time, so do not assume a client has always or will always identify with the same sexual orientation throughout their life.

Types of sexual orientation include:

- Heterosexual/Straight: Being attracted to the opposite sex or gender as oneself

- Homosexual/Gay/Lesbian: Being attracted to the same sex or gender as oneself.

- Bisexual: Being attracted to both the same and opposite sex or gender as oneself

- Pansexual: Being attracted to any person across the gender spectrum, including non-binary people

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Think about a patient you have cared for that did not come in with a significant other. Did you make any assumptions about that client’s sexual orientation or gender identity?

- Would there have been different risk screenings you needed to perform if they were part of the LGBTQ+ community?

- Think about what you know about psychological development during the teenage years. Why do you think suicide risk is so much higher among LGBTQ+ youth?

- Why do you think a robust support system is protective against suicide in this population?

- What is your experience or comfort level caring for transgender clients, and how do you think it impacts your care?

- What protocols could healthcare facilities implement to improve culturally competent care for this population?

Gender & Sex

Gender and sex play a significant role in health risks, conditions, and outcomes due to a combination of factors, including biological, social, and economic elements. Among the differences in health data related to gender are:

- Women are twice as likely to experience depression than men across all adult age groups (13).

- About 12.9% of school-aged boys are diagnosed and treated for ADHD, compared to 5.6% of girls, though the actual rate of girls with the disorder is believed to be much higher (5).

- A 2021 study showed that older women have a higher frailty index (69%) compared to older men (61%) (19).

- Heart disease is the leading cause of death in women, yet women are shown to have lower treatment rates for heart failure and post-heart attack care, as well as lower prevalence but higher death rates from hypertension than men (3).

It is also essential to differentiate gender and sex when practicing cultural competence in nursing.

Sex is the biological and genetic differentiation between males and females, whereas gender is a social construct of differences in societal norms or expectations surrounding men and women. Knowing this differentiation is essential for someone looking to better practice cultural competence in nursing and provide equitable and inclusive care.

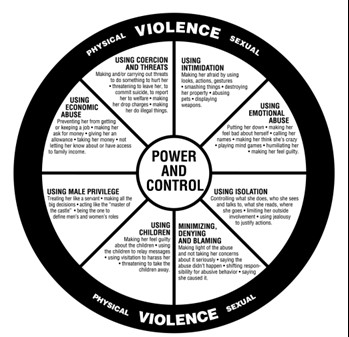

Some health conditions are undeniably attributable to the anatomical and hormonal differences of biological sex; for example, uterine cancer can only be experienced by those who are biologically female. However, many of the inequalities listed above disproportionately burden women due to the social and economic differences they encounter in society; for example, 1 in 4 women experience intimate partner violence as compared to 1 in 9 men (20).

What are the reasons for this? A lot of it has to do with how women are perceived in society, how their symptoms may present differently than their male counterparts, or how their symptoms are presented to and received by medical professionals.

- For centuries, any symptoms or behaviors that women displayed (primarily mental health-related) that male doctors could not diagnose fell under the umbrella of hysteria. The recommended treatment for this condition was anything from herbs, isolation, sex, or abstinence, and it is only in the last one hundred years or so that more accurate medical diagnoses began to be given to women. Hysteria was not deleted from the DSM until 1980 (26).

- Nair found that women were more verbose in their encounters with physicians and may not be able to fit all of their complaints into the designated appointment time, leading to a less accurate understanding of their symptoms by their doctor (19).

- A 2024 article notes that 40% of women felt rushed through doctor appointments or their concerns were not fully addressed (23).

- Symptoms of mental health disorders like ADHD may look different in girls than in boys. Girls with difficulty focusing may be categorized as "chatty" or "daydreamers" by teachers. In contrast, boys are more likely to draw attention for being hyperactive or disruptive when both are experiencing symptoms of ADHD and could benefit from treatment (7).

The way that teachers, doctors, and nurses view and respond to girls and women must be adjusted to close these gaps and ensure equitable care for men and women.

- Children who are struggling in school should be examined more comprehensively, and differences in learning styles should be widely understood.

- Screening questionnaires and standard preventive care are used when caring for clients in primary care.

- Social services should be utilized to help determine whether women are neglecting their own healthcare needs due to responsibilities at home.

- Medical professionals must be trained in the history of inequality among women, particularly regarding mental health, and proper, modern diagnostics must be used.

- The differences in communication styles of men and women should be understood when caring for patients.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Think about a patient you cared for recently and how they communicated their needs and symptoms to you. How might this have differed if they had been a different gender?

- In what ways do you think the history of “hysteria” in women may still be subtly present today?

- Why do you think it is essential for nurses to understand and address the differences between sex (biological) and gender (social construct)?

- Why might women’s symptoms be underrecognized or misdiagnosed compared to men’s symptoms, particularly for mental health conditions?

- What societal or historical factors surrounding women's health have impacted how women are perceived and treated in healthcare? How might those influences still be affecting today's healthcare system?

- How do you think having a care provider of the same gender may impact a client's care or even their perception of their care?

Religion

Religion can impact when patients seek care, which treatments they will participate in, and how they perceive their care. Even advanced technology in healthcare can be perceived as unsatisfactory if it violates the religious preferences of patients. Hence, healthcare professionals must know specific religious preferences to provide the most competent and sensitive care possible. Consequences of culturally incompetent care include:

- Adverse health outcomes due to not participating in care that violates their religious beliefs.

- Patient relationships with healthcare professionals can suffer if they feel disrespected or misunderstood, causing patients to delay or avoid seeking care altogether.

- Dissatisfaction with care can even lead to long-term trauma surrounding significant events like birth, death, or chronic disease if a patient feels uninvolved or disrespected in their care (28).

Many religions have different practices and ordinances, but we will cover some more central and common implications regarding health practices here. Typically, views on pregnancy/birth, death, diet, modesty, and treatment for illness are the most critical areas for healthcare professionals to understand. Providers must continue to educate themselves on the practices and preferences of various religions; it is essential to practicing cultural competence in nursing.

Disclaimer: Each religion has many variations, and not all practices may be the same. The following information has been sourced from "Cultural Religion Competency in Clinical Practice," written by Drs. Diana Swihart, Siva Naga S. Yarrarapu, and Romaine L. Martin (Swihart).

Buddhism

They study and meditate on life, cause and effect, and karma, working towards personal enlightenment and wisdom. They believe the state of mind at death determines their rebirth and prefer a calm and peaceful environment without sedating drugs. They have ceremonies around birth and death. Their diet is usually vegetarian (28).

Christian Science

Based on the belief that illness can only be healed through prayer, they typically choose spiritual healing for disease or illness prevention and treatment. They often refuse vaccines and delay treatment for acute illnesses. They avoid tobacco and alcohol but have no other dietary restrictions (28).

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints/Mormon

Heavily family-oriented, family involvement in major health/life events is essential—strict abstinence outside of heterosexual marriage. Fasting is required monthly, but it is exempt during illness. Blood or blood products are accepted. Abortion is prohibited unless it is a result of rape or the mother's life is in danger. Two elders present to bless those ill or dying (28).

Hinduism

It centers on leading a life that allows you to reunite with God after death. Believes in reincarnation, so the environment around dying people must be peaceful. The presence of family and priests during the end of life is preferable. After death, the body is washed and not left alone until cremated. Euthanasia is forbidden. Often vegetarian, the right hand is used for eating (28).

Islam

Belief in God and the prophet Abraham. Prayer is required five times daily. Observe Ramadan, a month of fasting and abstinence during daylight (children and pregnant women are exempt from fasting). Autopsies should only be performed if legally necessary. Must eat clean, halal food, excluding pork, shellfish, and alcohol. Female patients require female healthcare providers. Abortion is prohibited (28).

Jehovah’s Witness

Belief destruction of the present world is coming, and faithful followers of God will be resurrected. Do not celebrate birthdays or holidays. I believe death is a state of unconscious waiting. Euthanasia prohibited. Refuse blood and blood products. Abortion is prohibited. Pregnancy through artificial means (IUI, IVF) is not permitted (28).

Judaism

Belief in an all-powerful God and varying levels of interpretation/observance of laws and traditions. Cremation is discouraged or prohibited. Prayer is essential for the sick and dying; after death, the body is not left alone. Must eat kosher foods, excludes pork. Amputated limbs must be saved and buried where the person will one day be buried. Abortion is allowed in certain circumstances (28).

Protestant

Christian faith formed in resistance to Roman Catholicism. Autopsy and organ donation are acceptable. Euthanasia is not sufficient. There are no restrictions on diet or traditional Western medicine treatments (28).

Roman Catholicism

Christian faith is steeped in tradition and observance of sacraments. The clergy is present at the end of life for the sacrament of Last Rites. Avoid meat on Fridays during Lent. Mass and Communion on Sundays are obligations, and they may require a clergy member to visit during hospitalization. Abortion and birth control (other than natural family planning) are prohibited. Artificial conception is discouraged. Newborns with a grave prognosis need to be baptized (28).

To better practice cultural competence in nursing and improve the quality of care given that respects a patient’s faith and religious boundaries, one should focus on:

- Understanding fundamental differences and preferences between various religions and providing staff training is essential.

- We are encouraging families to participate in health decision-making where appropriate.

- We are providing interpreters where needed.

- Promoting an environment that allows clergy, healers, or other religious figures of comfort to visit and participate in care if desired.

- Providing dietary choices that are considerate of religious nutritional preferences.

- Recruiting staff that are minorities or of various religions.

- Respecting a client's views on controversial topics such as pregnancy/birth, death, and acceptance or decline of treatments, even if it conflicts with staff members' own beliefs (28).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Imagine you work on a maternity unit and are caring for a new mother who observes the Islamic faith. What needs might she have to feel respected and comfortable with her care?

- You are caring for a patient in the critical care unit who is a Jehovah's Witness. In what ways might this client's faith impact their care?

- How might the level of respect for a client's religious beliefs affect how they perceive their care, regardless of health outcomes?

- What challenges might occur if a client's religious practices conflict with standard medical practices, and how can you navigate such a situation?

- Suppose you have a different perspective on topics like pregnancy, death, or treatment of medical conditions than your client. Why is it important to remain nonjudgmental and not express your views?

Case Study

Scenario

Mr. Nadir is a 46-year-old male patient admitted to the hospital for postoperative pain management following a surgical hernia repair. Mr. Nadir practices Islam and expresses concern about halal foods that are free from pork or alcohol. He is also currently observing Ramadan and fasting during the day.

Culturally competent approach to care

The nurse assigned to Mr. Nadir includes his religious needs and dietary requirements in his chart. The nurse contacts the pharmacy and ensures that all his ordered medications meet halal guidelines. Acceptable foods are also ensured to be available during times when Mr. Nadir can break his fast. The nurse also arranges care around his prayer schedule. He is encouraged to contact a religious leader if he needs further guidance or information about medical exemptions that may be acceptable during his hospitalization.

Outcome

Mr. Nadir feels understood and respected, which reduces his anxiety about the hospital stay. The nursing staff, pharmacy, and nutrition services take a collaborative approach, ensuring that he can receive necessary medical care without compromising his religious beliefs. He expresses satisfaction with the care he received.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What problems might have arisen if Mr. Nadir did not express his religious needs and the nurse did not ask?

- What hospital policies or protocols could be in place to prevent information like this from going unrecognized?

- How might ignoring or being unable to accommodate Mr. Nadir’s needs during his hospitalization impact his overall trust in the healthcare system?

- How will this experience likely impact Mr. Nadir’s future willingness to seek care when he needs it?

- What resources could be used to support patients like Mr. Nadir?

Age

As the Baby Boomer generation ages, there is a growing number of older adults in the U.S. In 2016, 73.6 million adults over 65 were expected to grow to 77 million by 2034. As of 2016, 1 in 5 older adults reported experiencing ageism in the healthcare setting (25). As the number of older adults needing healthcare expands, the issue of ageism must be addressed. For providers looking to improve cultural competence in nursing practices, ageism must be addressed as it flies under the radar. Ageism is defined as stereotyping or discrimination against people simply because they are old. Ways in which ageism is present in healthcare include:

- Dismissing is a treatable condition as part of aging.

- Overtreating natural parts of aging as though they are a disease.

- Stereotyping or assuming a patient's physical and cognitive abilities purely based on age.

- Providers who are less patient, responsive, and empathetic to patients' concerns talk down to patients or do not explain things because they believe them to be cognitively impaired.

- Elderly patients may internalize these attitudes and seek care less often, forgo primary or preventative screenings, and have untreated fatigue, pain, depression, or anxiety.

- Signs of elder abuse may be ignored or brushed off as easy bruising from medication or being clumsy (25).

There are many reasons why ageist attitudes in healthcare may occur, including:

- Misconceptions and biases among staff members, particularly those who have worked with a frail older population, assume all older adults are frail.

- Lack of training in geriatrics and the needs and abilities of this population.

- Standardizing screenings and treatments by age may help streamline the treatment process but can lead to stereotyping.

- Changing this process and encouraging an individual approach may be resisted by staff and viewed as less efficient.

To combat ageism and make sure healthcare is appropriately informed to provide respectful, equitable care:

- Healthcare professionals can adopt a person-centered approach rather than categorizing care into groups based on age.

- Facilities can adopt practices that are standardized regardless of age.

- Facilities can include anti-ageism and geriatric-focused training, including training about elder abuse.

- Healthcare providers can work with their elderly patients to combat ageist attitudes, including internalized ones about their abilities (25).

Although it does not always appear first in a conversation regarding cultural competence in nursing

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever cared for two patients of the same age who seemed drastically different in their overall health and independence? Why do you think that is?

- Think about your attitudes about older adults. What biases or assumptions do you have about the cognitive and physical abilities of people who are 65? 75? 85?

- What can healthcare providers do to ensure equitable treatment of clients, regardless of age?

- How can healthcare providers empower older adults to advocate for their health and needs?

- What challenges may arise for a healthcare facility implementing practices to reduce ageism?

Veterans

Veterans are a unique population that faces many health concerns that are unique to the conditions of their time in service. Much of veteran health care is provided through the Veteran Affairs (VA) facilities, a nationalized form of healthcare involving government-owned hospitals, clinics, and government-employed healthcare professionals. Again, this course aims to educate providers on how to practice cultural competence in nursing; however, let's introduce the disparities found within this population by utilizing a few statistics.

- 1 in 5 veterans experience persistent pain, and 1 in 3 veterans have a diagnosis related to chronic pain (4).

- Approximately 12% of veterans experience symptoms of PTSD in their lifetime, compared to 6% of the general population, and 80% of those with PTSD also experience another mental health disorder such as anxiety or depression (4).

- More than 1 out of every 10 veterans experiences some substance use disorder (alcohol, drugs), which is higher than the rate for non-veterans (4).

- From 2022 to 2023, there was a 7.4% increase in homeless veterans (8).

- Veterans account for 20% of all suicides in the U.S., despite only about 8% of the U.S. population serving in the military (4).

- Disparities also exist within the veteran population and veterans who are of a minority race or female experience these issues at an even higher rate.

- For example, veteran women are more likely to experience homelessness than veteran men (8).

The causes of these troubling issues for veterans are multifaceted; some of them relate to the nature of work in the U.S. Military and increased exposure to trauma (particularly with those involved in combat), and some of them relate to the care of veterans, and their mental health during and after their service.

- 87% of veterans are exposed to traumatic events at some point during their service (4).

- Current data suggests fewer than half of eligible veterans utilize VA health benefits.

- For some, this means they are receiving care at a non-VA facility, and for others, it means they are not receiving care at all.

- Care at civilian facilities involves healthcare professionals who may not fully understand veteran issues (24).

- Less than 50% of veterans returning from deployment receive any mental health services (21).

All service members exiting the military must participate in the Transition Assistance Program (TAP), an information and training program designed to help veterans transition back to civilian life, either before leaving the military or retiring. The program is evaluated annually for effectiveness and includes components about skills and training for civilian jobs and individual counseling regarding plans after exit.

- Adding or strengthening components of TAP surrounding mental health care and utilization of VA healthcare services would be beneficial and help reduce disparities.

- Changing the military culture surrounding mental health to strengthen and mandate training and using debriefing for active-duty military could also be beneficial.

- Incentivizing the usage of the VA healthcare system for routine preventative and mental healthcare would help reach more veterans who may be in need.

- Additional training for healthcare professionals working within the VA with an emphasis on mental health disorders would ensure high-quality care for veterans utilizing their services.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- The Transitional Assistance Program was established in 1991. How do you think veterans' experiences of leaving or retiring from the military differed before and after this program was established?

- In what ways do you think that trauma is the catalyst for many of the other veteran-specific issues they experience?

- How could trauma better be handled for these patients to reduce their risk of all the other related issues?

- What are some specific challenges that are unique to caring for veterans?

- What protocols do you think healthcare facilities could implement to reduce health disparities in veterans?

Mental Illness & Disability

Disabilities have emerged as an under-recognized risk factor for health disparities in recent years, and this new recognition is a welcome change as more than 18% of the U.S. (15) population is considered disabled. Disabilities can be congenital or acquired and include conditions that people are born with (such as Down Syndrome, limb differences, blindness, deafness), those presenting in early childhood (Autism, language delays), mental health disorders (bipolar, schizophrenia), acquired injuries (spinal cord injuries, limb amputations, change in hearing/vision), and age-related issues (dementia, mobility impairment).

Public health surveys vary from state to state. Still, most categorize a condition as a disability based on the following: 1) blindness or deafness in any capacity at any age, 2) severe difficulties with concentrating, remembering, and decision-making, 3) difficulty walking or climbing stairs, 4) difficulty with self-care activities such as dressing or bathing, 5) and difficulty completing errands, such as going to an appointment, alone over the age of 15 (17).

Health disparities affecting people with disabilities can include the way they are recognized, their access and use of care, and their engagement in unhealthy behaviors. To practice cultural competence in nursing, understanding the disparities that those with disabilities face is essential.

- Due to variations in the way disabilities are assessed, the reported prevalence of disabilities ranges from 12% to 30% of the population (17).

- People with disabilities are less likely to receive needed preventative care and screenings (6).

- 1 in 6 disabled adults have not had a routine health check within the last year (6)

- 1 in 4 adults do not have a regular health care provider (6)

- People with disabilities are at an increased risk of chronic health conditions and have poorer outcomes (10).

- 40.5% of disabled adults are obese compared to 30.3% of adults without disability

- 10.4% of disabled adults have heart disease compared to 3.7% of non-disabled adults

- 16.6% of disabled adults have diabetes compared to 7.9% of non-disabled adults (6)

- People with disabilities are more likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors such as cigarette smoking and lack of physical exercise than people without disabilities (10).

Many of the health differences between those with and without disabilities come down to social factors. Compared to non-disabled people, individuals with disabilities are:

- Less likely to finish high school

- Less likely to maintain steady employment

- Less likely to have at-home access to the internet

- Have a lower annual income

- Have adequate health insurance coverage (6)

If access to necessary preventive and acute health care is to be increased for those with disabilities, much must be changed regarding the social determinants affecting this population. Community, state, and federal policy changes will be needed to provide the social and economic support these people need. Potential solutions include:

- Streamline and standardize the process of identifying people with disabilities so they can be eligible for assistance as needed.

- School programs to help people with disabilities graduate and find jobs within their ability level.

- Community participation ensures transportation, buildings, and facilities are accessible to all.

- Make internet access an essential and affordable utility, like running water and electricity.

- Address the inequities in health insurance accessibility and coverage.

- Provide social and economic support programs for parents of children with disabilities and provide transitional support as those children become adults (10).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever cared for a patient with a severe disability? Consider how even getting to the clinic or hospital where you work might be different or more challenging than for patients without a disability.

- What resources for people with disabilities are available in your community?

- How might those resources vary in surrounding areas?

- How might addressing social determinants of health (socioeconomic status, education level, neighborhoods, etc) improve health outcomes for people with disabilities?

- Why is it important to standardize the identification process, and how could this impact access to care for clients with disabilities?

Case Study

Scenario

Mrs. Donaldson is an 82-year-old woman who presents to her primary care provider with complaints of stiffness in her arms and legs, difficulty with balance, and a fine tremor in her right hand when playing piano at church. She reports feeling tired and slower in her movements lately.

Her primary care provider discusses typical signs of aging with her and recommends increasing physical activity, sleep hygiene, and a balanced diet. No further diagnostic workup is done.

Over the next 4 months, her symptoms worsen. The tremor becomes much worse, and she begins to have difficulty completing daily tasks. Her family encourages her to seek a second opinion, so she schedules an appointment with a neurologist who diagnoses her with Parkinson's disease.

Outcome

Because of her primary care provider’s assumption that her symptoms were due to Mrs. Donaldson’s advancing age, her diagnosis was delayed by several months, disrupting her quality of life and ultimately reducing the outcomes of her treatment.

Culturally competent alternative

Parkinson's presents subtly and may sometimes be mistaken for natural aging processes. Further evaluation, like a neurological exam, imaging, or additional testing, would have revealed a more severe diagnosis and given Mrs. Donaldson the prompt treatment she needed. Even if advancing age is a potential differential diagnosis, it should only be assumed to cause further workup.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How might this experience impact Mrs. Donaldson’s trust in the healthcare system?

- What steps could have been taken at Mrs. Donaldson’s initial visit to ensure she received a more thorough evaluation?

- How do you think implicit bias impacts the diagnosis of conditions like Parkinson's that typically affect older adults?

- Even though Mrs. Donaldson eventually received the correct diagnosis, how do you think her scenario might have been different if she had received a more thorough assessment at her first encounter for these symptoms?

- What role did patient advocacy (by the patient or her family) play in this scenario?

Conclusion

In short, cultural competence in nursing means that although a provider may not share the same beliefs, values, or experiences as their patients, they understand that to meet their needs, they must tailor their care delivery. Nurses are patient advocates, and they must ensure they provide equitable and inclusive care to all populations.

However, cultural competence in nursing is ever-changing, and it is the provider's responsibility to stay up-to-date to offer the best patient experience.

Connecticut Mental Health Conditions

Introduction

Mental health conditions are common in the United States, with one in five adults suffering symptoms ranging from mild to severe each year. Despite this fairly high prevalence, 2020 data indicates that only 46% of adults with a mental health condition received medical services related to those symptoms (10). Furthermore, experiencing one mental health disorder increases the risk of developing a second or third disorder by two to three fold (13). Comorbid mental health diagnoses also increase the severity of symptoms, negative impacts on quality of life, and risk of suicidal ideations (3)

Current practices surrounding mental health leave many people at risk of being undiagnosed or untreated and increased awareness and education is needed for medical professionals to help close these gaps in care. This Connecticut mental health training aims to provide a thorough understanding of certain common mental health disorders, how to screen for them and coordinate resources for clients in need, and how to navigate suicide prevention for optimum client safety.

Epidemiology

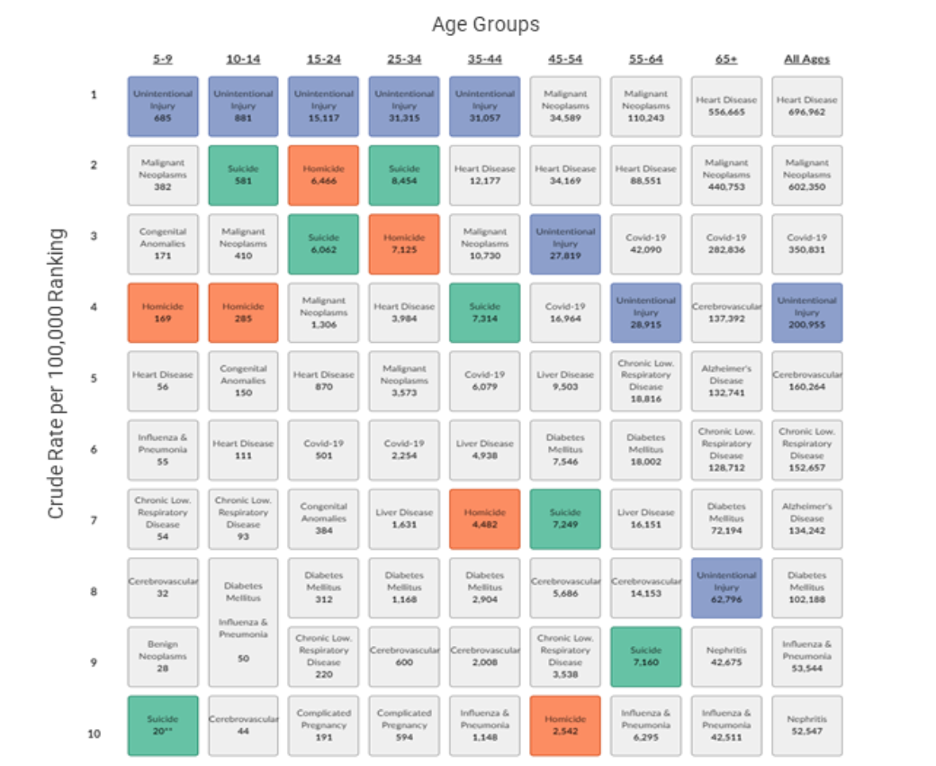

Every year, millions of people nationwide suffer from mental health related symptoms that impact their ability to work, attend school, maintain relationships, and enjoy their lives. Recent data indicates that one in five United States adults experiences symptoms of mental illness each year and one in twenty experiences severe symptoms (6). One in six United States children experiences mental illness symptoms each year and suicide is the second leading cause of death in the 10-14 year age group (6).

As of 2020, anxiety disorders were the most prevalent, with 19.1% of all US adults experiencing some form of anxiety annually. Depression is next, with a prevalence of 8.4%, Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) experienced by 3.6%, and bipolar disorder experienced by 2.8% of adults (6).

There is mild variance among races, with annual prevalence among races outlined as follows:

- Non-Hispanic multiracial people: 35.8%

- Non-Hispanic white: 22.6%

- Non-Hispanic American Indian: 18.7%

- Hispanic or Latino 18.4%

- Non-Hispanic black: 17.3%

- Non-Hispanic Asian: 13.9%

(6)

Women are more likely to experience mental illness than men, with 25.8% of women 15.8% of men reporting symptoms annually (NIH). Being part of the LGBTQ community is one of the greatest risk factors, with 47.4% of LGBTQ people experiencing mental illness (6).

In addition to the factors that increase risk of mental health disorders, experiencing mental health issues also increases other health related risks. Suffering depression increases the risk of cardiovascular and metabolic disorder by 40-50% over the rest of the population, depending on severity. Thirty-two percent of people with mental illness also experience substance abuse disorders, as compared to 10% of the general population (6). The rate of academic struggles and dropping out of school are 2-3 times higher for children and teens with mental health diagnoses, which in part contributes to the higher rates of unemployment (6.4% vs 5.1%) experienced by people with mental health disorders (6). On a more global scale, it is estimated over $1 trillion is lost in productivity due to depression and anxiety disorders each year (6).

On the severe end of mental health consequences is suicide, currently the 12th leading cause of death nationwide (12). Overall, there has been a slight decrease in suicide rates in recent years, declining from 14.2 per 100,000 people annually in 2000 to 13.5 per 100,000 people in 2020 (12). Still, suicide is a devastating problem with twice as many people dying by suicide as homicide in recent years. Risk varies by many demographic factors with men being about 4 times more likely to commit suicide than women across all ages. Among women, suicide rate is highest for those ages 45-64, at 7.9 people per 100,000. And among men, the rate is highest for those age 75 and older, at 40.5 per 100,000. By race, American Indians and White men are significantly more affected (12).

When looking at younger populations, the biggest risk factor seems to be sexuality and gender identity. Gay, Lesbian, and bisexual teens are 4 times more likely to attempt suicide than straight peers and transgender teens are 9 times more likely to attempt suicide than cis-gender peers. Each year, 45% of LBGTQ teens report experiencing serious thoughts of suicide at least once (6).

Despite these serious implications and high rates of prevalence, less than half of affected people receive appropriate, regular mental health services. These statistics are staggering. This is the reason of why the Connecticut Department of Public Health implemented the Connecticut mental health training CE requirement to improve mental health outcomes. Lack of proximity to resources, prescription problems, delayed or canceled appointments, and complications due to the pandemic or even just symptoms causing poor compliance all serve as barriers to appropriate treatment (6). Healthcare professionals are guaranteed to encounter patients with mental health needs no matter what area of healthcare they work in, and universal improvements in education and preparedness to deal with mental health concerns is desperately needed and can serve to improve outcomes for patients everywhere.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

-

Think about the population you serve...How often does your job involve assessing the mental health needs of your clients? Given the statistics above, do you think your attention to mental health is sufficient or needs to be increased?

-

If a client you encountered admitted that they were suffering from symptoms of depression or anxiety, what resources are available for you to connect them with? If you are unsure, how could you compile a list of resources?

Signs, Symptoms and Criteria for Common Mental Health Diagnoses

Unless you work specifically in mental health, you may only have a vague understanding of what exactly certain mental health diagnoses mean, how they are treated, or what symptoms your clients are dealing with. A more in depth understanding of how mental health problems present and diagnostic criteria is one of the first steps towards better detection and treatment for vulnerable clients. The Connecticut Department of Public Health added this CE requirement of Connecticut mental health training in order to better serve the patient population.

Depression

Known as Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) or Clinical Depression, this is one of the most common mental health disorders. While this disorder may stereotypically be known as being sad or down, the actual criteria for depression is much more detailed and nuanced (9). According to the Diagnostics and Statistics Manual for mental health (DSM-5), MDD is defined as experiencing at least five of the following symptoms for at least a two week time period and at least one of the symptoms must be one of the first two on the list:

- Sad, depressed, or even flat or detached mood most days, for the majority of the day

- Decreased or lack of interest or pleasure in any activities throughout the day

- Decrease in appetite or significant weight loss without trying to lose weight

- Slowed thought process and movement, noticeable by others

- Fatigue or low energy levels most days

- Feeling worthless or unnecessarily guilty most days

- Decreased ability to think, concentrate, or make decisions most days

- Recurrent thoughts of death, with or without a plan, or thoughts that things would be easier if one was dead (9)

The number, combination, and severity of symptoms will vary by individual. Typically symptoms are severe enough to interfere with a person’s ability to work, attend school, or maintain their relationships as well as they would like. People with depression may also experience excessive worries about their health or increased rates of general physical complaints like headache or abdominal pain. MDD may occur as a single episode, but often occurs in recurrent episodes, lasting for a few weeks to months and then resolving for a period of time before returning. Persistent symptoms lasting two years or more, though often less severe in intensity, is known as dysthymia. Depression can also occur from hormonal changes during or after pregnancy and is known as perinatal depression. Some individuals suffer from depressive symptoms only at certain times of year, typically in the dark and cold months of fall and winter in the northern hemisphere; this is known as seasonal depression (9).

It is important to separate depression from grief which is a response to loss with similar, often overlapping, but distinguishably different from depression symptoms. In grief, there is an identifiable loss, whereas depression can occur without any particular precipitating event (for “no reason”). Grief involves sad or hopeless feelings intermixed with feelings of joy or peace, whereas depression is persistently low mood. Being close to loved ones often offers comfort or healing in grief, but isolation and withdrawing are more common with depression. And with grief, thoughts of death may occur as a person desires to reunite with a deceased loved one, while in depression thoughts of death center around feeling worthless or hopeless and no longer wishing to live (4).

Risk factors for depression include personal or family history of any depressive disorder, certain medical conditions that negatively impact quality of life, or even medications taken for other conditions. Major life events or traumas, including death of a loved one, divorce, moving, job changes, birth of child, abuse, or traumatic events can all increase the risk of subsequent depression (9).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

-

How can you differentiate a bad day (or several) with many of the symptoms of depression, from a true diagnosis of MDD?

-

How might someone grieving the loss of a loved one present differently than someone with depression after the same loss?

Anxiety

All people experience worries or stress over things throughout their lives. But anxiety disorders extend beyond normal worries in their frequency and intensity, occurring often enough and at a severity level that interferes with a person’s ability to function at work, school, or in their relationships with others. There are several distinct disorders that fall under the umbrella of anxiety and the differences lie in the triggers and the expression of symptoms, but the criteria of excessive worry is a common theme across all anxiety disorders (8).

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is a common form of anxiety that involves a general sense of dread of anxiousness, typically about anything and everything rather than specific events. People with GAD may feel restless, on edge, have difficulty concentrating, become tired easily, be irritable or have difficulty regulating their emotions, have difficulty sleeping, or have frequent general physical complaints like headaches or stomach aches (8).

Panic disorder involves more extreme physical symptoms of anxiety, known as panic attacks. Sudden, intense bursts of anxiety involving a racing heart, chest pain, shortness of breath, shaking, intense feelings of dread, or an intense desire to flee a situation are considered panic attacks. They may occur in relation to stressful events or for no reason at all. Anyone can experience a panic attack, but experiencing them frequently and being unable to function at work, school, or home because of them is considered panic disorder (8).

Social anxiety disorder is anxiety triggered by situations with people outside of one’s home. This can be people you know, like classmates or extended family, or strangers like cashiers or healthcare professionals. Symptoms include feeling judged or watched by others, racing heart, being unable to speak up or speak clearly to others, avoiding eye contact, or feeling very self conscious (8).

Phobias are anxiety related symptoms that center on a very specific trigger or event. People with phobias will do everything they can to avoid the trigger, including refusing to go to a certain place or leave home. Common phobias include agoraphobia (fear of leaving home), blood, heights, airplanes, vomit or vomiting, certain animals (such as snakes, spiders, or dogs), needles or injections, or separation from parents (for children) (8).

Risk factors for anxiety include exposure to traumatic events (especially early in life), drug or alcohol use, frequent exposure to a stressful environment (at job or school), and family history of anxiety disorders. Certain medications and stimulants like nicotine and caffeine can increase the symptoms of anxiety (8).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

-

Have you ever felt so nervous about something that you wanted to stay home or avoid the event altogether? How do you think it might affect your daily life if you felt that same level of anxiety every day?

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a type of mental health disorder that develops as a response to experiencing a particularly dangerous, scary, or shocking event. An extreme response of “fight-or-flight” during a high stress event is very normal, but many people recover quickly, within a few days to weeks, and do not experience continued distress after the event is over. For other people, the intense symptoms of fear or anxiety continue long after the danger has resolved (11).

Symptoms that occur in response to an identifiable event, last more than a month, and are interfering with a person’s ability to function at work, school, or in relationships are considered to have PTSD. Symptoms include:

- Re-experiencing the event such as through flashbacks or nightmares

- Avoidance symptoms such as staying away from certain people, places, objects, or even music that serves as a reminder of the event

- Arousal symptoms of feeling on edge, angry, tense, easily startled, or having difficulty sleeping

- Cognition and mood symptoms such as difficulty remembering details surrounding the event, negative outlook on the world or about self, feelings of guilt or blame, lack of interest in things

- Children may experience symptoms of regression such as bedwetting or daytime accidents when previously continent, being unable to speak, acting out the event with toys, increased clinginess or fear of separation from parents or caregivers (10)

Risk factors for PTSD include experiencing war (both as a member of the military or a civilian), physical or sexual assault/abuse, car accidents, natural disasters, seeing someone be seriously injured or die, history of mental illness or substance abuse, and having few to no support systems in place during times of stress (11).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

-

Have you ever cared for a client who lived through a traumatic event? How did they talk about the event?

-

What sort of feelings or emotions did they seem to experience while discussing their trauma?

Suicide

Suicide by definition is the death of an individual from self-injurious behaviors and the intent to die from those behaviors. Reckless behaviors resulting in unintentional death are not considered suicide because there was no intent to die. People who attempt or commit suicide often feel worthless, hopeless, or that their life is a burden to others and the only escape from their symptoms or guilt is to end their life (12). Warning signs that individuals may be planning or preparing for suicide include increase agitation and substance use, withdrawing from others, researching methods of suicide, stating they have thought about or have the ability to commit suicide, sleeping too much or not at all, giving away possessions or calling/writing letters to say goodbye to loved ones, or a sudden and extreme improvement in depression symptoms (usually from the resolve to commit suicide) (2).

A suicide attempt is any self-injurious behavior engaged in as an attempt to die but which ultimately is non-fatal. Suicide attempts can be actions which do not even result in injury, but if death was the individual’s intent, it is considered a suicide attempt. Suicidal ideations are any thoughts, considerations, or detail planning related to ending one’s own life (12).

The leading method of suicide in recent years is firearms, accounting for more than half of all suicides (11).

Risk factors for suicide include existing mental illness (especially depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia), substance abuse problems, terminal health diagnosis (particularly those that are very painful), persistent bullying or relationship problems, unemployment, highly stressful life events like divorce, family history of suicide or personal past attempts, and childhood trauma or neglect. Having access to guns, knives, pills, or other potentially lethal materials increases the risk of suicide as well (2).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever cared for a client who was contemplating suicide? What life events had occurred leading up to these thoughts?

Case Study

Jason is a 78 year old male who presents at the Internal Medicine office for his annual physical. When the nurse is collecting vitals, she chats with him about his plans for the summer. He states that he and his late wife used to garden together and he has kept up with it for the last 3 years since her death but this year he does not feel up to planning it or doing the work. The nurse asks if he has other plans for how to occupy his time and he states he usually has a group of friends he gets coffee with twice a week, but he hasn’t been waking up early enough to go to it and has decided to sleep in instead. The nurse documents his vitals and reports off to the physician, attributing his “slowing down” to his advancing age. During the visit, his doctor asks how he is coping with his wife’s loss to which Jason replies, “I’m okay. It never gets easier, but you do get used to it.” The physician orders labs to check his iron levels for fatigue and provides a pamphlet for a support group for widows and widowers at the end of the visit. He recommends Jason follow up in another 3-4 months if his fatigue hasn’t improved.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

-

Do you feel confident that the nurse and the physician have a thorough understanding of Jason’s mental health at the end of this visit?

-

What are Jason’s risk factors for mental health diagnoses? What symptoms of depression is he experiencing?

-

How might grief resources fall short of addressing Jason’s symptoms?

Screening

Regardless of which area of healthcare you work in, there will always be clients who are struggling with mental health symptoms, even if that is not their primary reason for seeking care at your facility. Routine and standardized screening for these symptoms can help ensure more clients who need help are identified and prevent many from falling through the cracks. Earlier detection of symptoms ultimately leads to better mental health outcomes as well, so simple and routine screenings serve to improve identification and distribution of care to those in need. Improving mental health outcomes is the primary goal of Connecticut implementing this CE requirement of Connecticut mental health training. So who should undergo screening, when should the screenings occur, and what are some of the best or most common screening tools available?

Let’s start with children since over 50% of all lifetime mental health disorders first appear by age 14.. At every wellness visit, it is recommended to ask general questions about family psychosocial wellness such as childcare resources, availability of food, parent coping with the stressors of parenthood, and normal psychosocial development in the child such as language, eye contact, bonding with family members, play, and age appropriate response to praise and consequences. Families where problems are suspected should be evaluated further. Starting at age 11, the use of more streamlined screening tools is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and/or Pediatric Symptoms Checklist (PSC) should be used annually to detect increased risk of depression, anxiety, or suicidal thoughts. The CRAFFT questionnaire is recommended annually for screening of substance use, starting at age 11. For children who seem anxious or where excessive worries or behavior problems are a concern, a SCARED questionnaire can assess more specifically for anxiety disorders (1).

Once into adulthood, the PHQ-9 is still a reliable and easy to use tool and should be administered at all annual wellness visits. The General Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) tool is also quick to administer and can pick up on clients who may be experiencing excessive worries (5). In more acute settings like urgent cares or emergency departments, a simple screening question such as “Do you feel safe at home?” can determine situations that may need acute interventions for clients who may not be receiving regular primary care.

In addition to annual screening, healthcare providers should be aware of life events that may increase a person’s risk of experiencing a mental health disorder and perform additional screening as needed. In obstetrics and gynecology settings, women should be screened throughout pregnancy and postpartum for perinatal mood disorders using an Edinburg Questionnaire. Pediatric offices can also screen mothers of infant clients since women often see their child’s pediatrician much more frequently than their own obstetrician or midwife (5). Older adults are more likely to be experiencing declining health, chronic medical diagnoses, or life events such as retirement or the loss of a spouse that increase their risk of depression or anxiety. Assuming their age alone is the cause of certain symptoms should be avoided, while energy and activity levels may indeed decline in later life, a lack of interest or pleasure in things or feelings of hopelessness are not normal signs of aging and should not be brushed off. Updated information on recent life events is important and increased screening should be done accordingly. War veterans, disaster or abuse survivors, and others may find themselves seeking care for physical symptoms related to trauma, but their mental health should be considered and assessed immediately after the event as well as regularly for several months afterwards (5).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

-

Think about the population you work with. What factors (age, life stage, general health) put them most at risk for mental health symptoms?

-

What screening questionnaires, if any, do you routinely use at your facility? What additional screening tools could you use to improve your detection rates?

Taking Action

The next step in closing the gap for early detection of mental health disorders is knowing what to do when clients screen positive or when they come to you specifically with a mental health concern or symptoms. A primary goal of the Connecticut mental health training is to prepare nurses with the knowledge and resources needed to get paitents on the right plan of care. Many facilities are surprised once they begin screening, just how many clients present with positive results or the need for further help.

The first thing to do is gather more information directly from the client. Ask about symptoms they have been feeling, how long it has been going on, recent life events that may be contributing to these feelings, and ways in which the symptoms have been impacting their performance at work, in school, or in other aspects of life. Gather a family history that focuses specifically on mental health disorders to better assess disorders for which a client is at risk. Determine the client’s overall safety; the best way to do this is to ask directly if they are having thoughts of wanting to harm themselves or others. This will help determine if intervention is needed urgently or if a more routine connection with resources is appropriate (2).

Once more thorough information has been gathered about a client’s particular scenario, providers can determine the best course of action and what resources to connect them with. It is useful for facilities to have a list of resources available. Appropriate resources include providers who can diagnose and prescribe treatment for mental health disorders (this can often be done in primary care settings, but specialists like psychiatry may be more appropriate), therapists or counselors, group therapies or support groups with common themes, and crisis resources like suicide hotlines or facilities that can be accessed 24/7 in the event of a crisis. When connecting clients with resources, plan for appropriate follow up as well to ensure they received the help they needed (2).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

-

What resources are available in your area for routine therapy or counseling? Are there any support groups that you know of for grief or loss, LGBTQ people, or veterans?

-

How do you think it might make a client feel if they admitted to struggling with depression or anxiety and were not given any resources or next steps at the end of their experience at your facility?

-

What are the risks involved with not appropriately addressing their symptoms at the time of care?

Suicide Prevention

On a broad scale, healthcare professionals can participate in suicide prevention by advocating for screening and early detection of mental illness, as well as identifying risk factors and protective factors for their clients to determine who may need connection with available resources. On a community health level, strengthening available resources and the community’s access to them can promote social change needed for prevention (7).

On a more individual level, familiarity with what to do when encountering suicidal clients is always useful, though the actually frequency at which you encounter such clients may vary greatly depending on where you work. If you have concerns or a client fails a screening tool, it is always okay to ask them outright if they have thoughts of wanting to hurt themselves. It is a myth that asking someone this will give them the idea and no studies indicate asking this would contribute to suicide risk. If a client indicates they are having thoughts of suicide or self harm, the next steps should be to determine how often these thoughts are occurring and if they have a plan. It can feel awkward to ask these types of questions, but it is extremely important for client safety and studies indicate that most people would like the help and support extended to them. If they admit to having a plan, the next step is to determine if they have the means to enact the plan. If they say they want to take a lethal dose of pills, determine what medicines they have available to them; if they say they have thought about using a firearm, determine if firearms and ammunition are accessible to them (7).

Clients with an active plan and the means to enact said plan will need crisis intervention and likely involuntary hospital admission. Anyone with thoughts of suicide, even passive ones with no plan, will require further evaluation with a counselor or provider experienced in mental health. Specific plans moving forward for these clients is beyond the scope of this course, but often involve the development of Safety Plans, initiation of psychiatric medication, and connection with resources such as individual or group therapists. The important thing for healthcare professionals in general is to be able to determine when clients are a risk to themselves or others and ensure they are connected with resources before leaving your care (7). This is what the Connecticut Department of Public Health wants to educate nurses on and is why they implemented a CE requirement of the Connecticut mental health training.

Revisit Case Study

Let’s take a look at Jason’s case again and consider how things might have gone differently with better mental health protocols for the facility.