Course

Connecticut APRN Bundle Part 2

Course Highlights

In this Connecticut APRN Bundle part 2, we will learn about various topics applicable to APRNs in the state of Connecticut.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 30 , including 14 pharmacology contact hours.

Course By:

Various Authors

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

Flap Surgery: The Basics

Introduction

Flap surgeries can be a critical treatment for various wounds to provide bulk tissue. It is a tad more detailed than skin grafts, as it involves a circulatory supply from a donor site to a recipient site. It is important to recognize what flap surgery entails, the indications, and types of flap surgeries. Nurses should be knowledgeable on care plans and assessment for flap surgery, positioning techniques, patient education topics, and how to identify possible complications such as infection or flap dehiscence. Are you ready to dive into the interesting course topic of flap surgery?

Flap Surgery: What is it?

Flap surgery involves removing healthy, live tissue from one location of the body and transporting it to another area that needs it for healing purposes. Flap surgeries are commonly used to transfer this healthy tissue to areas of lost skin, fat, muscle movement, and/or skeletal support (9). A tissue flap has its own system for vascularization and does not depend on the recipient’s wound bed to perfuse the donor tissue, which differs from non-vascularized skin grafts (8). Essentially, a flap is tissue with a substantiated blood supply that is transferred from a donor site to a recipient site. If the flap surgery was a party, the damaged host site would send out an invite saying “BYOB- Bring Your Own Blood-Supply!”

The flap continues to be fed by the same blood supply from where it was taken, until new blood vessels grow from the recipient site and the wound heals completely. The recipient site is called the primary defect and the wound that is created by cutting, lifting, or sliding the flap to fill the primary defect is called the secondary defect (8). The base, or pedicle, of the flap is the tissue that remains attached to the skin adjacent to the defect, it contains the vascular supply required for initial flap survival (8).

Surgeons have used skin flaps to repair wounds and tissue damage for centuries. The term “flap” was derived from the Dutch word “flappe” during the 16th century (8). Around 700 B.C., the Sushruta Samhita (an ancient text on surgery and medicine) first documented a technique of reconstructing a large nasal tip defect with a flap of cheek tissue (8). New techniques are constantly being developed to meet various needs. Flap surgeries are used for a variety of wounds from pressure ulcers to breast reconstruction following mastectomy.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever cared for a patient following a flap surgery?

- Do you recognize the difference between flap surgery and skin grafting?

- Are you familiar with the vascular structure at deeper skin levels?

- Can you discuss how significant improvements could have been made over the past hundreds of years?

Types of Flap Surgeries

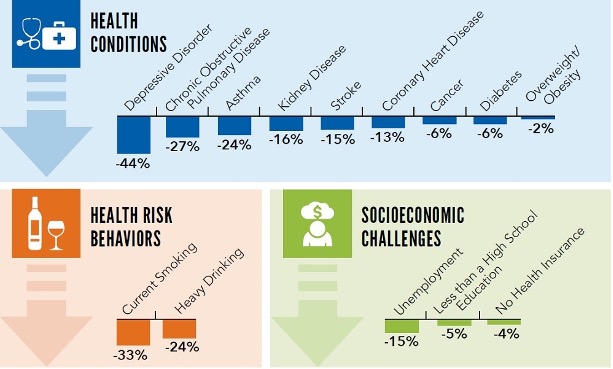

Flap surgeries are classified in the following ways: (9)

- Blood supply

- Type/composition of tissue

- Distance of the healthy site from the recipient tissue

- Locations of donor and recipient tissue

- Movement

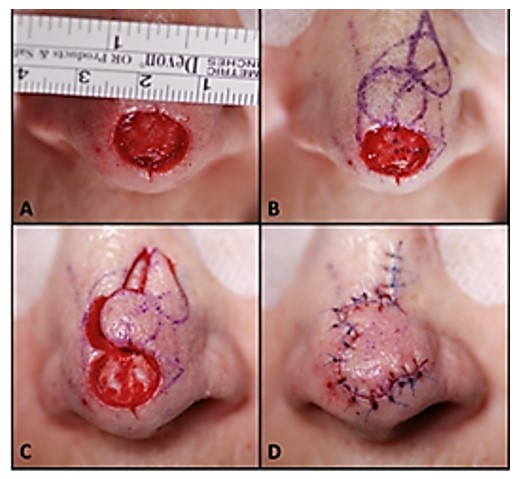

Figure 1: Classification of Flaps

Classification by Blood Supply

Flaps can be named based on the supply of blood. The understanding of the circulation of blood to the donor tissue is critical when describing the type of flap. The terms random and axial are used to categorize the blood supply.

- Random Flaps

- Not based on a specific vessel

- Uses subdermal plexuss (network of blood vessels between the deep reticular portion of the dermis and subcutaneous fat tissue beneath it) (7)

- Axial Flaps

- Single, direct cutaneous artery in the axis of the flap

- Named according to the pathway

Classification by Tissue Type

Flaps can be named according to their composition. The tissue composition may be skin, fascia, muscle, bone, nerve, cartilage, or a combination. Fascia is the thin lining of connective tissue that surrounds and holds each blood vessel, bone, nerve fiber, and muscle in place (7). Cutaneous refers to the layers of skin. Pedicle flaps are those that are still attached to the original site and the other end is moved to cover the recipient area; a free flap is an area of tissue completely removed from one part of the body and surgically placed in another area (8).

Common flaps: (5)

- Skin Flap: Skin and superficial fascia

- Fascio-cutaneous Flap: Skin and deeper layer of deep fascia

- Fascial Flap: Deep fascia only

- Muscle Flap: Muscle only

- Myo-cutaneous Flap: Muscle and skin

- Osteomyocutaneous Flap: Muscle, bone, and skin

- Bone Flaps: Bone (vascularized)

- Innervated Flaps: Flaps that contain a motor or sensory nerve and function

Fascio-cutaneous Flap

This flap includes the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and the underlying deep fascia (5). The musculocutaneous perforators or direct septocutaneous branches of major arteries act as vascular supply (5). Perforator flaps are named based on their location, arterial supply, or the muscle of origin. The indications for fasciocutaneous flaps are based on its advantages of being more simple, reliable, thin, and easily mobilized (8). These flaps can come from many potential donor sites (8).

Muscle Flap

Muscle tissue can be used as donor tissue in flap surgery. Surgeons may utilize the benefits of flap surgery in wound closure following major surgeries. For example, median sternotomy (vertical inline incision through the sternum of the chest) is the most commonly used approach for cardiac surgery (6). Cardiac surgeons face the risk of deep sternal wound infections following surgery, which is associated with significant morbidity and mortality rates. The use of soft tissue flaps for sternal closure is helpful for patients with extensive tissue deficits after debridement (6). It can be used for immediate or delayed closure. Options for donor tissue for sternal flap closure include the pectoralis major, rectus abdominis, and latissimus dorsi muscles, or an omental flap (6).

Remember, flaps are transplanted with blood supply intact, so it’s important to know the supply. For instance, if tissue from the pectoralis major muscle is used, the nurse must recognize that this muscle’s primary and secondary blood supply is the thoracoacromial artery and perforators from the internal mammary artery (6).

Musculocutaneous Flap

This type of flap, which includes muscle and skin layers, is often used when the area to be covered needs more bulk and an increased blood supply. Musculocutaneous flap surgery is frequently used to rebuild a breast after a mastectomy (5).

Bone Flap

A bone flap is comprised of bone with a vascular supply. An example of this flap surgery is for a surgical site infection (SSI) following a craniotomy; in this procedure, operative debridement occurs, and the bone flap is removed, cleaned, and replaced (4). An alternate therapy for this is titanium cranioplasty (implant instead of native bone flap), which has similar outcomes.

Classification by Location and Movement

- Local flap: Donor tissue is located next to the area receiving the tissue; the skin remains attached at one end to allow the blood supply to be left intact (5).

- Regional flap: Donor tissue is a section that is attached by a specific blood vessel.

- Distant flap: Donor and recipient tissues are distally located from each other. This flap surgery involves detaching and reattaching skin and blood vessels from one site of the body to another site; microsurgery is used to connect the blood vessels (5).

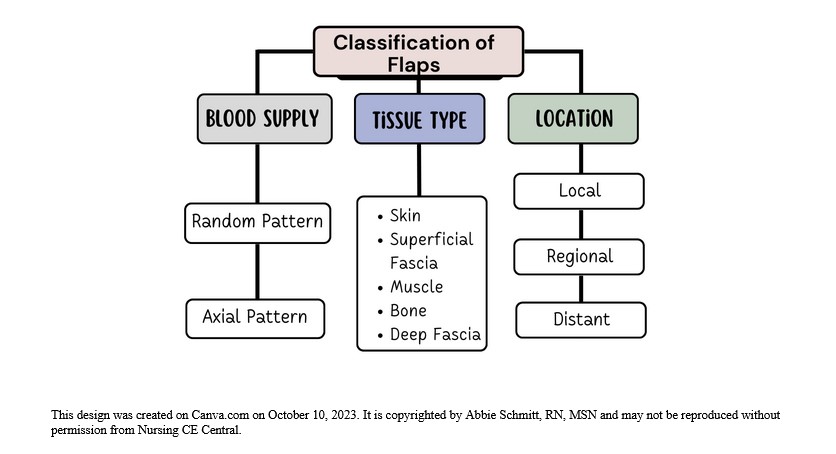

Figure 2: Example of Flap Type

The movement of the flap is also used to describe flap surgery. You may hear terms such as advancement, sliding, rotation, and pivotal. Sliding flaps is when the tissue is moved or "slid" directly into the adjacent defect without "jumping" over other tissue (5). Advancement flaps are considered simple movements for local flaps and fall within the group of sliding flaps. Pivotal (geometric) flaps include rotation, transposition, and interpolation (5). Local, random pattern flaps are common for the reconstruction of cutaneous defects.

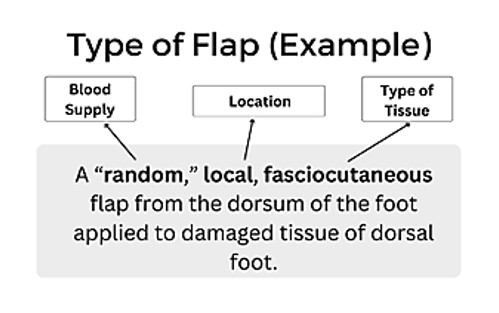

Image 1: Image of a local flap surgical procedure to cover nasal tip defect/wound (9)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Are you familiar with the differences in skin, muscular, bone, and nerve tissue?

- Can you think of benefits of using a local, pedicle flap over a free flap?

- Can you discuss how fasciocutaneous flaps may have more advantages and more potential donor sites?

- Are you able to recognize the general location and complexity of a surgical note that says “local, random, skin flap with pivotal manipulation at midline of forehead”?

Indications for Surgery

There is an incredible breadth of possibilities for flap reconstructive surgery, from small, skin-only defects to large, multi-tissue defects. There is a wide range of etiologies, such as traumatic, oncological, and congenital (9). The transferred tissue flap can contain multiple types of tissue, including skin, muscle, nerve, fascia, and bone (9). The larger the volume of tissue transferred, the greater the need for perfusion. A common indication is the need for a large bulk of tissue. Flaps are helpful when wounds are large, complex, or need large amounts of tissue for closure.

General Indications:

- Protection of the greater vessels

- Correction of congenital defect

- Abdominal wall reconstruction

- Deep, gaping wounds

- Reconstruction after tumor excision

- Trauma

- Debridement procedure to remove infected or necrotic tissue

- Venous ulcers (non-healing)

- Pressure ulcers (non-healing)

- Breast reconstruction

- Rhinoplasty

- Scar Revision

- Skin Cancer

- Burns

Each type of wound has unique indications. Commonly, skin flap surgery is required when a wound is too big for the edges to be brought together directly, so the flap covers the area and depth of the wound (10).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Do you have experience in caring for a patient with a deep, healing wound?

- Have you ever cared for a patient following a tumor removal?

- Can you discuss why debridement of the recipient site is essential prior to flap placement?

- Can you name various methods of wound closure? (ex: sutures)

Risks versus Benefits

Flap survival depends on factors of blood flow, angiogenesis (formation of new blood cells), vascularization, edema, wound closure tension, postoperative complications (hematoma/seromas) and infection (8). Before the initial incision, the flap is fully vascularized and viable, but once the flap is raised, it is immediately ischemic. The tissue can survive up to 12 to 13 hours of avascularity at 37°F and many research studies have proven it is viable even longer (8). This time is invaluable to preserve the tissue. Sufficient blood flow through attachment of the base of the flap is essential in the initial 24 to 48 hours after surgery (8). There is a risk for loss of tissue with no meaningful contribution to the needed area, along with a new wound. This risk reminds me of a neighbor who once removed carpet from a closet to patch carpet in a bedroom, only to find the cutting was too small and they were left with two gaping carpet holes.

There is also risk for bleeding, infection, or necrosis at both sites. A recent study found that more than 27% of patients will experience a minor complication (wound dehiscence, infection, fistula, and donor-site problems) after surgery, and 6% of patients will suffer a major complication (flap failure, pneumonia, and cerebrovascular accidents) following surgery (11). Chronic flap complications can also be aesthetic in nature; include scarring, contracture, color/texture mismatch, and lack of hair growth. Patients may experience pain or numbness at the sites on a chronic basis as well (9).

Most flap surgeries are considered safe with a low complication rate, and surgeons report that flap surgery is not avoidable in certain circumstances. However, the surgery preparation itself and anesthesia presents considerations for elderly patients or those with heart disease, uncontrolled diabetes, smokers, or bleeding disorders (2). Nutrition is a key factor in these surgical procedures. Poor nutritional status has been linked with a greater incident of negative outcomes (11). The healthier the patient is before surgery increases, the chances of reduced complications, so glucose control and weight management are examples of risk reduction strategies.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Do you feel confident with patient education methods for explaining risks versus benefits?

- Can you name reasons informed consent for flap procedures is not only required, but ethical?

- Do you have experience in educating patients on diabetes and the importance of glucose control in wound healing?

- Are you familiar with your facility’s medical literature database?

Preparing for Surgery

Patients undergoing flap surgery need an abundance of education on what to expect throughout this procedure. There are many opportunities to optimize patient outcomes before going to the operating room. Preoperative education, for example, has been suggested to have an important, positive effect on clinical outcomes (11). Many patients are also experiencing other issues, such as cancer diagnoses, poor circulation, comorbidities, bed sores, among others. Taking time to holistically prepare each patient is essential.

Addressing Comorbidities and Other Conditions

Multiple studies have found an increased surgical complication rate in patients with diabetes mellitus, older age, female gender, malnutrition, anemia, and nicotine intake (11). Prior to surgery, the goal is to improve and optimize the modifiable conditions as much as possible, for instance, reduction in nicotine or improvement in glucose control and anemia. Further, patients with advanced cancer can have hypothyroidism affecting postoperative healing if left uncorrected (11). Non-modifiable factors such as a history of radiotherapy, age, advanced cancer stage, or chronic kidney disease, cannot be altered prior to surgery, but can guide care planning and education following the surgery.

Adequate nutrition before and after flap surgery has been demonstrated in numerous studies to improve outcomes. An estimated 35% of patients with head and neck cancers present in a state of malnutrition, and the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommends that all patients undergo a comprehensive preoperative nutritional assessment and consult with nutritionist (11). Improved nutrition status can hopefully yield enhanced wound healing problems and reduction in risk of infection.

Lab assessment is key to preparation before flap surgery. An example is assessment for anemia prior to surgery. Patients who are anemic at the time of free flap surgery have been found to have poor outcomes (11). Remember, hemoglobin transporting the oxygen to the sites of flap insertion and removal is vital to the survival of the flap. Preoperative hemoglobin values below 10 g/dL have historically been a significant predictor of flap failure and thrombosis (11). A hematocrit level of 30 to 40% with normovolemic hemodilution is ideal to optimize patient outcomes.

Blood transfusions during or following surgery impacts flap success as well. Transfusion can increase blood viscosity and immunosuppression, thus leading to decreased blood flow and flap compromise from poor perfusion (11). Studies also show a link between blood transfusions and increased wound infections (11). Steps and treatments should be taken prior to surgery to improve anemia or blood component abnormalities to give these patients a greater chance for successful flap surgery.

Preoperative considerations should include: (9)

- Patient age

- Diabetes status

- Smoking history

- Atherosclerosis

- Peripheral vascular disease

- Steroid use

- Previous surgeries

- The extent and location of the defect

Providing Preoperative Instructions

A lack of education, difficulty in understanding complex medical information, fear and anxiety about the surgery, and language barriers are some of the challenges a patient for surgery may have. Patients may also have limited access to reliable health resources or be unable to recall important information due to stress or preoperative medications. As a result, they may not be fully informed about the surgical process, potential risks, and postoperative care.

Preoperative education list:

- Assess the patient’s level of understanding.

- Each facility should have a preoperative teaching program with specific content on surgery, but you must assess if the patient understands this information.

- Review specific pathology and anticipated surgical procedure.

- Verify that consent has been obtained / signed.

- Informed surgical choices and consent for the procedure is required, not only a signature.

- Use resource teaching materials, and audiovisuals as available on flap surgery and implement an individualized preoperative teaching plan.

- Preoperative or postoperative procedures and expectations, output (urinary and bowel) changes to expect following surgery, dietary considerations, anticipated intravenous (IV) lines and tubes (nasogastric [NG] tubes, drains, and catheters).

- Preoperative instructions: NPO guidance prior to surgery, shower or skin preparation, medications to take and hold, prophylactic antibiotics or anticoagulants, anesthesia premedication.

- Discuss postoperative pain management plan and options.

- Some patients may expect to be pain-free or are hesitant to take narcotic agents.

- Provide education and encourage practice of coughing and deep breathing.

- Confirm and recheck the surgery schedule, patient identification band, chart, and signed operative consent for the surgical procedure.

- Offer pastoral spiritual care or counseling.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some examples of pertinent laboratory values to assess prior to surgery?

- What are normal values of hemoglobin and hematocrit?

- Do you consider pain management a “one size fits all” care plan?

- Are you familiar with pastoral and spiritual counselors and supportive resources within your organization?

Post-Operative Considerations

This section will cover assessment, drains, positioning, and negative pressure wound therapy during the post-operative period.

Assessment

Frequent monitoring of free flaps in the acute postoperative period is important. It is strongly recommended that flap assessments are performed at least hourly for the first 24 hours postoperatively, then continued at a reduced increment for the duration of the patient's hospitalization (11). Each facility should have standing orders for flap assessment based on the directive of the surgeon or regulatory body.

In addition to conventional assessments of flaps (physical exam of flap warmth, turgor, capillary refill, color, and Doppler assessment of the vascular pedicle), many adjuncts have been developed including implantable Dopplers to assess blood flow (11). Assessments should include a head-to-toe physical assessment and a focused wound assessment. A focused cardiovascular (circulation and perfusion) and integumentary assessment is appropriate. Review of lab work indicative of healing status, hemodynamics, and infection should be a priority. Standard post-operative assessments following anesthesia, such as respiratory and orientation, should be performed according to facility protocol.

Assess circulation of the flap:

- Color of the flap (dusky, blue, pink, pale)

- Warmth

- Dry/Intact? Leaking Fluids?

- Changes in size

- Edema

- Indications of hematoma (sutures over the flap pulling apart, or palpable crepitus beneath the skin)

Assess amount and type of exudate (drainage): (3)

- Amount (scant, small/minimal, moderate, or large/copious)

- Color and thickness: (7)

- Sanguineous: fresh bleeding

- Serous: clear, thin, watery plasma

- Serosanguinous: serous drainage with small amounts of blood noted

- Purulent: thick and opaque; color can be tan, yellow, green, or brown (this is an abnormal finding and should be reported to physician or wound care provider)

Use of Doppler to assess deeper circulation of flap: (11)

- Color duplex ultrasound

- Near-infrared spectroscopy

- LASER Doppler flowmetry

- Implantable Doppler (useful for buried flaps)

Assess circulation distal to the flap:

- Capillary refill

- Color

- Temperature

- Pulses

- Edema

Drains

Drains may be used for removal of fluid around both the donor and recipient surgical areas to enhance healing (7).

Patients may have the following drains after flap surgery:

- Jackson Pratt (JP) drains

- JP drains are closed-suction devices that remove fluids from the surgical sites.

- JP drains contain a flexible bulb that has a plug that can be opened to remove collected fluid.

- Each time fluid is removed from the JP drain, the nurse should squeeze the air out of the bulb and replace the plug before releasing the bulb.

- This suction creates a vacuum that pulls fluid into the drainage tubing and bulb.

- Penrose drains:

- A Penrose drain is a soft, flexible tube inserted into the surgical site that drains fluid away from the wound bed (7).

- Nurses should assess the drain and express fluid when appropriate to prevent accumulation.

Positioning

The goal of positioning following flap surgery is to promote and improve tissue perfusion. Positioning and elevation of the flap recipient will promote venous return and reduce fluid accumulation to improve tissue perfusion. Activity, exercise, and repositioning improve tissue perfusion. Massage of the erythematous area is avoided because damage to the capillaries and deep tissue may occur (10). Patients should never lay on the wound and extremities should never “dangle” (if the donor or recipient site is on the extremities). Positioning may require creativity when there are multiple drains, NG tube, wound therapy devices, IV tubes, and multiple dressings. Positioning should be free of restrictive clothing and flap sites should be visible for assessment of dressings. It is imperative for the surrounding skin to be sanitary and free of debris.

Negative Pressure Wound Therapy

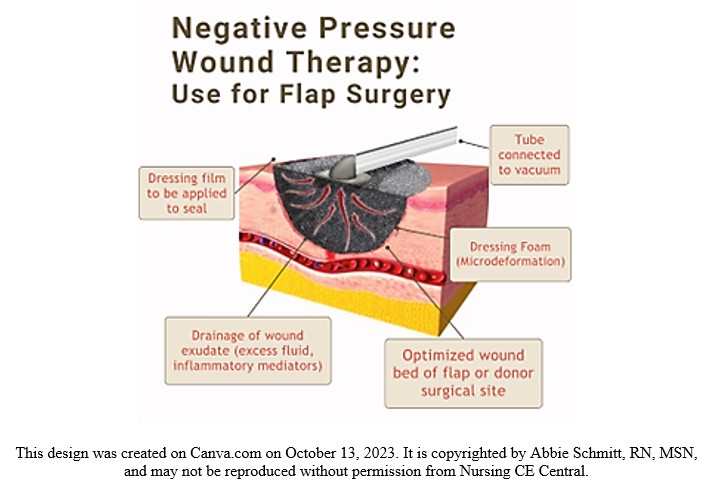

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) is typically used for soft-tissue salvage after the development of complications after flap surgery. For example, NPWT may be applied if an infection occurs in the donor or recipient flap. Immediate postoperative application of NPWT over the flap coverage is not as common (2). However, nurses should be aware of this treatment, the application, and its mechanisms of action.

NPWT is also known as a wound vac. NPWT uses sub-atmospheric pressure to help reduce inflammatory exudate and promote granulation tissue in an effort to enhance wound healing (4). The idea of applying negative pressure therapy is that once the pressure is lower around the wound, the gentle vacuum suction can lift fluid and debris away and give the wound a fighting chance to heal naturally. NPWT systems consist of a sterile foam sponge applied to the wound bed, a semi-occlusive adhesive cover, a fluid collection system or cannister, and the suction pump (1). The foam sponge is applied to the wound and covered. A fenestrated tube is embedded in the foam, the wound is sealed with adhesive tape to make it airtight, and the machine delivers continuous or intermittent suction, ranging from 50 to 125 mmHg (1).

Figure 3. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy Visual

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever completed a focused wound assessment that resulted in abnormal findings that were anticipated?

- Can you name examples of pertinent laboratory values to assess following general surgery?

- Have you ever used or witnessed the use of a doppler in assessment of proper circulation?

- Can you describe the importance of positioning in tissue perfusion?

Home Care and Patient Education

Educating clients and caregivers about wound care and skin integrity empowers them to actively care for their flap sites. With proper wound cleaning, dressing changes, and preventive measures, individuals can confidently perform their own self-care and enhance the healing process. The use of pamphlets, printouts, websites, and referrals to specialists will give the patients a stronger foundation of knowledge.

- Wound Assessment

- Teach the patient and caregiver about skin and wound assessment, ways to monitor for signs and symptoms of infection, complications, and proper healing.

- Signs of Infection

- Signs of a localized wound infection include redness, warmth, tenderness, and abnormal purulent drainage around the wound.

- Importance of proper nutrition, hydration, and methods to maintain tissue integrity

- Adequate caloric intake and balance of protein and essential vitamins has been shown to improve the healing of flaps (3).

- Dressing changes, wound cleansing, and hand hygiene

- Methods to prevent skin breakdown

- The flap surgery is often for the treatment of a deep pressure wound, so education is needed on impaired skin integrity due to friction.

- Common areas: Sacrum, heels, elbows.

- Avoidance of raising the head of bed often, causing weight to be applied to sacrum.

- Importance of turning, mobility, and ambulation

- Pain management

- Medications

- Heat/cold therapy applications and precautions

- Negative Pressure Wound Therapy devices (wound vac)

- Home healthcare is applicable for these devices and should be changed by a certified individual, but patients should be aware of basic care and troubleshooting.

- Drain maintenance

- Showering restrictions

- Reduction of stress and tension at wound site

- Avoid constipation, strenuous movements, and lifting

- Restrictions vary for location of flaps and per surgeon instructions

- Follow-up appointments

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you describe assessment findings that indicate infection after flap surgery?

- Are you familiar with various drains such as JP drains?

- What do you think are some fears among patients going home or to a long-term care facility after flap surgery

Flap Dehiscence or Loss

Flap dehiscence is a complication in which the incision made to either the donor or recipient site reopens. A flap loss refers to the flap not re-establishing blood flow and surviving, leading to necrosis of the tissue. As we mentioned earlier, the survival of the flap is impacted by blood flow, new vascularization and tissue formation, edema, wound closure tension, postoperative complications (hematoma/seromas), and infection (8).

Prevention Strategies

Nurses should apply their basic knowledge on causes of wound dehiscence. Factors that influence dehiscence risk include the ability to synthesize collagen, strength of suture material, closure technique, and stress on the incision, such as coughing, strenuous movement, or obesity (7). Consider areas that have greater stress and tension, such as the abdomen. Dehiscence is most common following abdominal flap surgeries (7). NPWT has been shown to be a great preventative measure for wound dehiscence as studies found a roughly 50% reduction in stress and tension at the incision site with its use (7). This reduction in stress is attributed to the reduction in subcutaneous fluid accumulation and enhanced healing time.

The location of the flap surgical sites will impact prevention. For example, immobilization and stabilization devices are unique to sites such as the abdomen, chest, extremities, and sacral region. Infection prevention measures for wounds are essential for nursing care. Incisions from flap procedures also have a higher chance of opening if the wound becomes infected (7). Prevention of hematomas is also meaningful, including the use of blood thinners. However, the safety precautions for blood thinners is different for each client.

Management and Treatment

It is estimated that 80% of free flaps can be salvaged if dehiscence or compromise is recognized early enough (11). As we mentioned, it is more common for flaps that are removed from (or applied to) the abdomen to open. The following terms describe the depth:

- Superficial dehiscence: the skin wound alone opens, but the rectus sheath remains intact.

- Full thickness dehiscence: the rectus sheath fails to heal and “bursts,” with protrusion of abdominal content.

- This commonly occurs secondarily to intra-abdominal pressure (example: ileus) or poor surgical technique.

The treatments for flap compromise will be determined by the provider once a cause is identified. Treatment may be a return to the operating room for additional surgical intervention or a simple evacuation of hematoma through suctioning.

Recovery

The focus of recovery is the healing and thriving of the flap site and surgical wounds. The time of flap healing varies, and some may heal much quicker than others. There are four phases of wound healing to recognize: hemostasis, inflammatory, proliferative, and maturation (7).

- Hemostasis. This phase begins immediately after surgery when platelets release growth factors that alert various cells to start the repair process.

- Inflammatory. This process involves vasodilation so that white blood cells in the bloodstream can move into the wound to begin cleaning the wound bed. Signs include edema and erythema.

- Proliferative. This phase generally begins a few days after the injury and includes capillary repair and growth, granulation tissue formation, collagen formation, and wound contraction (7).

- Maturation. During this phase, collagen continues to be created to strengthen the wound and fill in the wound gaps.

The healing process can be enhanced in many ways, including nutrition therapy, topical agents, compression therapy, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT). The recovery process for flap surgery will include management of pain and discomfort, disturbance of body image, impaired skin integrity, swelling, bruising, and gastrointestinal upset.

Outcomes for recovery should be measurable and achievable. Each patient will have unique recovery goals, integrating comorbidities and psychosocial aspects.

Examples of Patient Outcomes following flap surgery: (3)

- Patient safety: Patient will be able to attain safety by maintaining intra- and extra-cellular environment.

- Healing of wounds: Wounds should heal properly, complications will be prevented or maintained

- Management of pain

- Prevention of further damage or skin breakdown

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How would you describe the process of healing?

- Can you name some underlying causes of flap dehiscence?

- What are some strategies to prevent infection of the surgical site?

Conclusion

As discussed throughout this course on flap surgery, nurses are a key team member in the care and survival of flaps. Hopefully you now understand what flap surgery is, the indications, and types of flap surgeries. Critical knowledge includes pertinent assessment, drain or NPWT management, patient teaching, and prevention and management of possible complications.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you name the various ways to classify flaps?

- Why do you think it’s important to classify flaps according to their blood supply?

- What do you think the reason is for flap surgeries following mastectomies and breast reconstruction?

- Can you name various indications for flap surgery following a burn?

- What are comorbidities that may impact wound healing?

- Can you name common risks of surgeries?

- Can you think of reasons why elderly patients may have poor outcomes following flap surgery?

- Can you identify modifiable and non-modifiable pre-operative considerations?

- What do you think are some common fears and uncertainties among patients prior to flap surgery?

- Can you name teaching topics for a patient who is scheduled for a flap surgery?

Diabetic Ketoacidosis Management

Introduction

Diabetic ketoacidosis is considered one of the most life-threatening complications of diabetes mellitus. More importantly, it is also one of the most preventable complications of diabetes. Through proper education and empowerment of persons with diabetes to self-manage this chronic medication condition, the overall mortality rates associated with this complication have steadily declined in the United States. An interdisciplinary team approach (including medical providers, social workers, case managers, and community resources) has been proven to reduce recurrences of DKA in vulnerable populations. (2)

Definition

DKA, or diabetic ketoacidosis, is defined as the potentially life-threatening medical condition that occurs in people with diabetes. While it usually occurs in persons with type 1 diabetes mellitus, who are dependent on daily insulin injections, it may also occur in individuals with type 2 diabetes for a variety of reasons (underlying physiologic stress, such as an acute infection or trauma, or uncontrolled blood glucose levels and missed routine diabetic medications).

In an acute case of diabetic ketoacidosis, the body is not producing enough insulin to move glucose into the cell for energy, and the liver then begins to break down fat for fuel instead, producing ketones. This buildup of ketones in the body results in ketoacidosis. Left untreated, diabetic ketoacidosis can lead to a diabetic coma and eventual death. (3)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- As you begin this course, think about the diabetic patients you have cared for in your professional career.

- Do you have family or friends in your life that have been diagnosed with diabetes?

- What are your concerns over their self-management ability of this chronic medical condition?

- What areas of diabetes self-management do you consider the highest priority when you are delivering patient discharge instructions?

Epidemiology

Epidemiology is the study of how often a disease process occurs in different populations. By studying the rates of occurrence, epidemiologists are able to evaluate treatment options and develop long term strategies to lower the risk of ongoing or recurrent disease related episodes.

Diabetic ketoacidosis is currently a leading cause of both morbidity and mortality in children with Type 1 diabetes. It usually occurs at the time of the initial diagnosis in as much as 30-40 percent of the children in the United States alone. In children living with a confirmed Type 1 diabetes condition (previously diagnosed), these percentages decrease to average rates of 6-8 percent annually.

The drastic reduction of such occurrences is believed to be directly related to ongoing patient and family education and medication adherence. Diabetic ketoacidosis is potentially life-threatening, but it is for the most part, also preventable. Throughout this educational offering, key components of patient education in diabetic self-management, including reducing the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis, will be discussed (4) (5).

By comparison, other countries, challenged by annual income, healthcare access, cost management, and food insecurity, do not fare so well. Various studies were funded by the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Ltd. Several countries included in these studies were deemed “LLMIC” (low and low middle-income countries). Countries, including Haiti, Ethiopia, Senegal, Nepal, and Tanzania, to name a few were found to have inadequate supplies, medications, and equipment to both initially diagnose, and successfully manage diabetes mellitus long term. Critical items necessary for the treatment and stabilization of acute diabetic ketoacidosis were in even shorter supply. These barriers to treatment resulted in delayed or missed diagnosis, increased overall complication rates and premature deaths.

“Evidence from single-center studies suggest that DKA in new-onset T1D is more common in LLMICs compared to upper and upper-middle income countries, with rates ranging from 62.2 to 77.1% in Nigeria, 69.8% in South Africa, and 92.1% in Sudan. In comparison, in upper and upper-middle income countries in North America and Europe the rates range from 14.7% (Denmark) to 42.0% (France”). (6)

Ongoing education of healthcare professionals and patients/families alike, coupled with availability of and easy access to self-management medications, and monitoring equipment, positively affect DKA related health outcomes and quality of health and well-being.

The development of insulin delivery systems (insulin pumps) has further positively impacted the rate of DKA occurrence. Patient comfort, ongoing education, streamlined medication delivery and enhanced monitoring systems have afforded patients with diabetes a better understanding of their condition and empowered them to successfully self-manage their health conditions. While reported rates of DKA in previously diagnosed persons with T1DM were 6.3% in one study, that number decreased to 2.2% at 3 years out.

Ongoing improvements in closed insulin delivery systems medication continues to improve (lower) DKA occurrence rates, when compared to those previously using multiple daily injection therapy. The development of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices, in addition to insulin delivery systems, provides for early detection and treatment of both hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia. The addition of remote app devices further allows constant monitoring and two-way communication between patients, family members, and even healthcare providers.

Sadly, the population identified as being at highest risk for DKA is that of children who are uninsured/underinsured, lacking the insurance coverage for many closed delivery medication systems as well as specialty care (pediatric endocrinology) provider access.

The acute complications associated with DKA account for a high percentage of premature deaths in T1DM patients under the age of 30 years old. (7) Given these statistics of prevalence and incident rates, DKA is an ever-increasing global concern which is best addressed and managed through ongoing, patient specific disease management education.

The prognosis for DKA worsens in the presence of coma, hypotension and in the presence of severe (chronic and acute) comorbidities. Yet, with early identification, ongoing education, and improved glucose monitoring/treatment options, DKA, often life threatening, is also highly preventable. The goal, therefore, is to ensure all patients with diabetes mellitus are given equal opportunity to access both the education and materials necessary to successfully monitor their health condition. (8)

Pathophysiology

Diabetic ketoacidosis occurs when the body is under stress and responds with an increase in catecholamines, cortisol and growth hormones. The release of such hormones decreases the ability of insulin, further increasing insulin resistance and resulting in serum hyperglycemia. Without cellular glucose for energy the body then begins to break down fat and protein for energy, resulting in increased levels of serum ketones. The combination of hyperglycemia and ketosis, as well as dehydration and various electrolyte imbalances, form the basis of diabetic ketoacidosis. (9)

While it is believed that the omission of insulin (nonadherence/ noncompliance, or mechanical failure of insulin delivery systems) accounts for the largest percentage of DKA admissions, other factors may be responsible for the development of this condition. Any disease process that increases insulin resistance, impairs insulin secretion, or interferes with carbohydrate metabolism may contribute to the onset of acute diabetic ketoacidosis in a vulnerable, health compromised patient.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Diabetic ketoacidosis is caused by the underlying presence of hyperglycemia, ketoacidosis and ketonuria. Early signs and symptoms may include any of the following:

- Generalized weakness and fatigue.

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diffuse abdominal pain.

- Decreased appetite and anorexia.

- Decreased/ altered levels of consciousness, such as mild disorientation and confusion.

- Dry skin and mucus membranes and decreased perspiration

- Tachycardia (increased heart rate) and tachypnea (increased respiratory rate)

- Acetone/ketone smell on breath

- Significant weight loss (usually a rapid onset in the newly diagnosed Type 1 diabetes mellitus patients)

- A patient history of noncompliance with prescribed insulin therapy (due to coexisting medical issues in which patient may have intentionally stopped insulin due to decreased food/fluid intake), costs factors (unable to afford prescribed therapy) and missed insulin doses (mechanical failure of the patient’s current insulin delivery system).

Additional signs and symptoms may be present, related to the patient’s age. While an adult patient would be able to verbalize symptoms, a child may not be able to do so, especially in cases where the diagnosis of T1DM is done during their initial presentation to an emergency department for suspected DKA.

In all cases, there may be other factors (illness, injury, medication side effects) that cause DKA to occur; thus, thorough examination and diagnostic testing must be done in all cases prior to initiation of treatment. Likewise, discharge planning and ongoing follow-up care must be patient specific to address behaviors and treatments required for optimal health maintenance.

Teens/Young Adults

In the teenager/ young adult population, the following symptoms may occur: (11)

- Increases in urination, thirst, and appetite.

- Unintentional/ unexplained weight loss despite increases in food and fluid intake.

- Changes in energy level (increased fatigue)

- Vision changes

Please note that normal growth and development stages/patterns in a teenager/young adult will influence glucose metabolism (related to hormone levels).

Young Children

In the young children’s population, symptoms usually strike suddenly and, unlike the adult population, are usually not related to a specific lifestyle or dietary practice. Most children present with the following symptoms:

- Increased urination

- Increased thirst

- Fatigue

- Vision problems (blurred vision)

- Acetone/ketone “fruity smell” on breath

- Unexplained weight loss, often despite appearing to eat (and drink) more.

- Changes in mood and behavior

Infants/Toddlers

In the infant/toddler population, symptoms may present as follows:

- Increased food and fluid intake (always appearing thirsty despite normal fluid intake)

- Frequent urination (in the potty-trained child, this may present as a new onset of bed wetting behaviors)

- Increasing fatigue and changes in normal activity levels

- Unexplained weight loss despite increased food and fluid intake

- Increased occurrences in diaper rashes (suspected increase in yeast infection)

- Fruity/acetone smell to breath

- Unusual behavior (child specific)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Your patient with DKA appears to be “noncompliant” with his prescribed insulin therapy. What factors may be contributing to his failure to take medication as directed?

- What nursing interventions can be done with/for this patient to increase adherence to his current medication regimen?

- Unexplained weight loss in a young adult may indicate diabetes. What other medical conditions could be causing unexplained weight loss in this age group?

- How would you address these concerns with your patient/ their family members?

Etiology

Etiology: Causes of Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Hyperglycemia and low insulin levels lead to diabetic ketoacidosis. Common causes include the following:

- Acute illness, altering a person’s intake of food or drink, makes glucose management more difficult. This is a two-fold situation. The person with diabetes, recognizing the change in their normal food/fluid intake may also choose to intentionally decrease/skip their routine diabetic medications to avoid episodes of hypoglycemia.

- Insufficient levels of insulin due to the demands of normal growth and development patterns in children and young adults.

- Missed insulin doses (intentional decision to take inadequate doses, inadvertently held doses, inaccurate dose amounts, clogged insulin pump tubing).

Other causes of DKA, unrelated to insulin dose administration, are thought to be related to increased stress levels (inflammation/ infection) and normal hormone disruption, physiologic stressors. Persons with Type 2 diabetes may experience DKA due to prolonged, untreated hyperglycemia. (12), (13)

- Myocardial infarction

- Neurological stroke

- Motor vehicle accident with physical injuries (inflammatory response to blunt force/penetrating trauma)

- Abuse of alcohol and illegal drugs

- Medication side effects (diuretic and corticosteroid *use) see below

- Severe or prolonged illness (such as pneumonia and urinary tract infection/ urosepsis/wound infections)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Why do you think that the number of diabetes cases continues to rise worldwide, despite advances in medication and related treatment options?

- How do you think the healthcare industry can better address diabetic patient education?

- What factors do you think negatively affect the overall health and well-being of persons with diabetes (lack of care, knowledge deficit, health literacy, access to care, costs of care)?

- What can you do as a healthcare professional to improve the health outcomes of patients with diabetes?

Etiology: Precipitating Factors

Common precipitating factors for diabetic ketoacidosis include the following (14):

- Poor compliance with prescribed insulin therapy (intentional, nonintentional)

- Infections (especially T2DM in the elderly/ adult population)

- Newly diagnosed diabetes (especially T1DM in the pediatric/juvenile population)

- Physiologic based stressors, including coronary syndrome, cerebral vascular accidents, ischemic injuries, shock like states, chronic alcoholism, illicit drug use and certain antipsychotic medications.

Etiology: Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Corticosteroid Use

Diabetic ketoacidosis is related to long term corticosteroid usage. yperglycemia has been reported in a large percentage of patients who are using corticosteroids long term, often as high as “64-71%”. The elevated glucose levels combined with the ongoing physiologic stressors warranting use of these medications, increases the risk of DKA. The benefit/risk of using these medications long term must be assessed, especially in patients with pre-existing metabolic risk factors. Ongoing patient monitoring is essential to lower the risk of long-term complications. (15) (16).

Risk factors that “may” increase the likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes after long term steroid usage include the following:

- Overweight (BMI 25.0 -29.9 percent) / obesity (BMI 30 percent or above)

- History of gestational diabetes

- History of polycystic ovarian syndrome

- History of family members with type 2 diabetes

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Your patient, who is recovering from an acute myocardial infarction, has been started on insulin therapy for hyperglycemia. She is adamant that she is “not diabetic” and refuses to take insulin injections. How would you explain to this patient the connection between physiologic stress and hyperglycemia?

- What patient education, regarding insulin and hyperglycemia, would be appropriate for this patient?

- What follow-up care would be appropriate for this patient?

- Would this patient benefit from a referral to a diabetes education/management program at this time?

Treatment

Emergency Treatment

The initial or emergency treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis may require complex, frequent monitoring, often necessitating an intensive care admission. The following generic guidelines refer to intensive care nursing management. Please refer to your specific organization for nursing protocols related to DKA management. Many facilities have strict admission guidelines to ensure the appropriate use of intensive care resources. With respect to patients with DKA, suitable ICU admissions may include the following:

- A newly diagnosed diabetic during an episode of DKA

- Any infectious disease condition that triggers an episode of DKA

- An episode of DKA occurring concurrently with a physiologic stressor event (acute myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident/stroke)

The goals of emergency treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis are multifactorial and listed below. Interventions will include, but not be limited to, insulin intravenous infusions, hourly vital sign monitoring (or more frequent), and hourly glucose checks.

- Treatment/correction of dehydration with IV fluids

- Treatment of hyperglycemia with insulin therapy

- Treatment of electrolyte imbalances

- Treatment/correction of acid-base imbalance

Initial/Emergency treatment of DKA includes (20):

- Initial assessment and stabilization ABC airway, breathing and circulation.

- Aggressive fluid therapy to restore circulating volume.

- Isotonic saline IV infusion

- IV with dextrose component once glucose level 200-250mg/dl

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- With regards to your current workplace/unit, are there any specific order sets (“standing orders”) for ICU admissions?

- What “standing orders” are currently in place for a suspected diabetic ketoacidosis patient?

- What additional “order sets” would be initiated if a patient with DKA was found to be febrile (102F) with suspected pneumonia?

Laboratory Findings

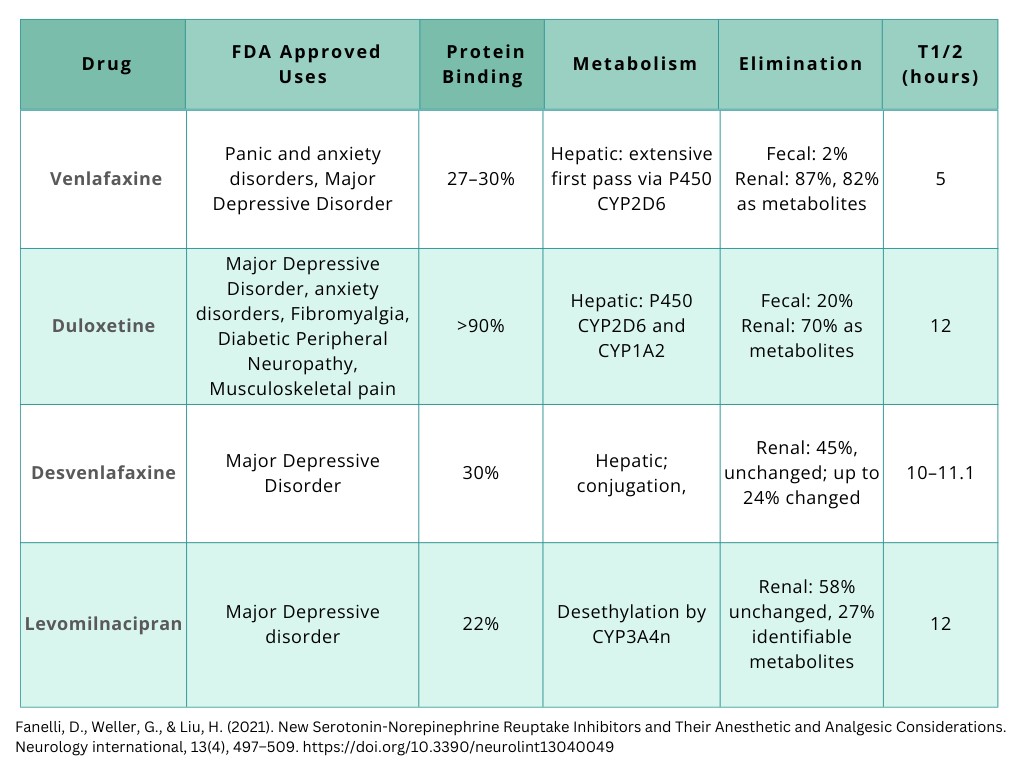

The following laboratory ranges provide a generic overview of normal ranges and abnormal findings associated with DKA (17) (18) (19). The confirmation of acute diabetic ketoacidosis is dependent on both laboratory findings as well as patient assessment. Please refer to your specific medical organization (unit specific) for further guidance and treatment parameters.

- Serum potassium levels: Normal range (3.5 to 5.0 mEq/L) hyperkalemia range approximately 5.0 to 5.5mEq/L.

- Serum sodium levels: Normal range (137 to 142 mEq/L) severe hyponatremia range approximately 125mEq/L or lower; severe hypernatremia range above 145mE/L

- Serum Amylase level: Normal range (40 to 140 units per liter) (U/L); may be elevated in cases of pancreatitis/ pancreatic inflammation, which may coexist with DKA

- Serum Lipase level: Normal range (0-160 units per liter) (U/L); may be elevated in cases of pancreatitis/ pancreatic inflammation, which may coexist with DKA

- Serum Osmolality level: Normal range 275-295 mOsm/kg: may be elevated to between 300-320 mOsm/kg in DKA

- Arterial blood gas analysis: Arterial ph below 7.3 (normal range 7.35-7.45)

- Anion Gap: Normal 4-12 mEq/L ; levels above > 10 may indicate existing acidosis in DKA

- Serum glucose level (normal fasting below 100mg/dl). Hyperglycemia range above 250mg/dl

- Serum ketone level (normal negative); serum ketones detected in blood; usually greater than 5mEq/L

- Serum bicarbonate level (normal 22-29 mEq/l); usually less than 18mEq/L

- Anion gap level (normal 4-12mmol/L); usually greater than 12 mmol/L)

| Lab Test | Normal Range | DKA | Comment |

| Potassium | 3.5-5.0 mEq/L | >5-5.5 mEq/L and above | |

| Sodium | 137-142mEq/L |

<125mEq/L hyponatremia >145 mEq/L hypernatremia |

|

| Amylase | 40-140 U/L | >140U/L | Elevated with pancreatitis |

| Lipase | 0-160 U/L | >160U/L | Elevated with pancreatitis |

| Arterial PH | 7.35-7.45 | Below 7.3 | |

| Serum Osmolality | 275-295 mOsm/kg | 300-320 mOsm/kg | |

| Anion Gap | 4-12 mEq/L | >10 mEq/L existing DKA |

|

| Glucose | < 100mg/dl | >250mg/dl | |

| Ketone | Negative | >5mEq/L | |

| Bicarbonate | 22-29mEq/L | <18mEq/L | |

| Anion Gap | 4-12mmol/L | >12mmol/L |

To rule out physiologic stressors associated with the development of DKA (systemic infections, acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, urosepsis), refer to your medical organization (unit specific) guidelines regarding these additional diagnostics:

- Serial blood and wound cultures

- Serial EKG and Troponin levels

- Sputum cultures and sensitivity

- Urinalysis and culture with sensitivity

- Chest Xray

Fluid Resuscitation Guidelines

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends the following initial fluid resuscitation in the adult population; additional boluses may be required after each hourly reassessment: (21). Please refer to your unit specific guidelines regarding fluid boluses, and fluid resuscitation. Caution in use with patients with preexisting heart failure, kidney failure or other medically indicated “fluid restrictions”.

0.9% SC (Sodium Chloride Solution) initially as a 15–20 mL/Kg bolus for hemodynamic resuscitation

- then 250–500 mL/h of fluid until glucose is normalized (usually faster than DKA resolution)

- then 150–250 mL/h until DKA resolution

- For the replenishment, 0.45% SC (Sodium Chloride Solution) unless hyperglycemia-corrected hyponatremia is present.

In the pediatric population, fluid resuscitation boluses are indicated in children who present with the following symptoms: (22)

- Dry mucus membranes

- Poor skin turgor

- Lethargy; altered level of consciousness.

- Nausea and vomiting

- Tachycardia and tachypnea

- Kussmaul type respirations (deep and labored respiratory breathing patterns)

Fluid recommendation: 10–20 mL/kg bolus of isotonic saline given over 30–60 mins.

Insulin Therapy and Acute Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Intravenous use of insulin is preferred in patients with acute diabetic ketoacidosis, as subcutaneous absorption of insulin would most likely be ineffective in light of dehydration.

Intravenous continuous infusion of insulin at a rate of at 0.14 U/kg/hour or

Insulin bolus of 0.1U/kg, followed by insulin continuous infusion at a rate of 0.1U/kg/hour.

Hourly (or more frequent glucose checks) with a decrease in insulin delivery dose when glucose level is 250mg/dl or less. At this time, insulin dose is further decreased to 0.05 or 0.1U/kg hourly until DKA is resolved.

- Patients, once stabilized and deemed able to eat, can be transitioned to subcutaneous insulin administration and routine glucose monitoring (point of care/ POC glucometers)

Laboratory Tests Guidelines Therapy Goals

- Serum glucose levels below 200mg/dl

- Serum bicarbonate level greater than 15mEq/L

- Serum potassium level 4.0 -5.0 mEq/L

- Venous pH greater than 7.30

- Anion gap equal to/less than 12eEq/l. (23)

Electrolyte Imbalance (Hyperkalemia-> Hypokalemia)

Serum potassium levels are usually high/elevated due to the cellular changes occurring as the result of acidosis and decreased insulin. Electrolyte replacement should be monitored very closely in diabetic ketoacidosis. During the rehydration/ volume restoration phase and insulin administration, extracellular potassium shifts back into the intracellular space (causing hypokalemia). In addition, insufficient insulin levels may deplete various serum electrolytes; thus, frequent serum electrolyte levels with appropriate intravenous replacement ensure proper cellular activity.

Treatment-Related Complications

- Hypoglycemia (blood glucose levels below 70mg/dl); treat; accordingly, patient should be transitioned to subcutaneous insulin injections when serum glucose level 200-250mg/dl, and patient is able to tolerate oral intake.

- Hypokalemia (blood potassium levels below 3-3.4 mmol/L); intravenous therapy to include potassium supplements; oral supplements as tolerated once patient transitions to diabetic diet.

- Cerebral edema

Cerebral Edema

Cerebral edema, or brain swelling, occurs for a variety of conditions (brain tumors, blunt trauma, inflammatory conditions, and even infections). Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyponatremia can cause cerebral edema. (24) Cerebral edema is the leading cause of mortality in children. A normal ICP (intracranial pressure) reading is 7-15mmHG; an increased reading in excess of 20-25mmHG, coupled with the following symptoms, may be indicative of cerebral edema.

Initial symptoms of cerebral edema may include the following:

- Headache

- Visual changes (double vision (diplopia) or blurred vision)

- Changes in speech/ ability to talk/ personality.

- Nausea and vomiting

- Changes in level of consciousness (lethargy-> unresponsiveness)

- Changes in respirations/ difficulty breathing

Symptoms that may indicate worsening of cerebral edema.

- decorticate and decerebrate posturing.

- cranial nerve palsies

- fluctuating level of consciousness

- sustained heart rate deceleration,

- increased vomiting, headache, and lethargy

Confirmation Testing:

- CT (Computerized Tomography) scan

- MRI Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Treatment for DKA Related Cerebral Edema

When cerebral edema is confirmed by radiologic testing, the administration of Mannitol (or hypertonic sodium) is recommended as follows (25) (26):

- 0.5-1 g/kg intravenous mannitol may be given over the course of 20 minutes and repeated if no response is seen in 30-120 minutes.

- If no response to mannitol occurs, hypertonic saline (3%) may be given at 5-10 mg/kg over the course of 30 minutes.

- Additional treatments may be warranted, including diuretics, corticosteroids, and possible surgical intervention (to prevent herniation syndrome).

Nursing Care and Management

Nursing Care: Patient Placement

Initial/hourly (or more frequent) assessment to include the following:

Due to the frequency of monitoring and medication administration during the acute phase of DKA, patients are usually placed in the Intensive Care Unit. ICU treatment often includes hourly physical assessments (intake, output, neurological assessment, vital signs; frequent laboratory testing (glucose testing); and rapid identification of complications (cerebral edema, hypoglycemia, hypokalemia).

Transfer to a step-down unit usually occurs when the patient is fully awake, tolerating oral intake (both solid food and liquids), vital signs are stable, and fluid and electrolyte replacements are complete. The average timeline may be 1-2 clinical days. The focus of care now shifts to discharge planning, patient education, and ongoing management.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What is your current workplace policy of ICU admissions?

- What parameters are used to determine which in-house unit a patient is transferred to?

- Do you feel that patients with acute DKA could be successfully managed on a step-down unit? Why/Why not?

Nursing Care: Acute Phase

- Monitoring of vital signs, level of consciousness/ neurological status, urine output

- Administration of IV fluids as ordered.

- Frequent blood glucose assessment and insulin administration

Nursing Care: Patient Education, Discharge Planning, and Follow-up Care

- Compliance with medications, healthy diet, glucose monitoring, sick day management

- Signs and symptoms of infection

- Importance of follow-up care with primary medical provider/endocrinologist

- Lifestyle behavior changes (smoking cessation, physical activity, healthy diet)

- Medical Alert ID bracelet or wallet insert regarding chronic medical conditions and medication.

- Coordination of follow-up care to ensure ongoing medical support, educational services and financial assistance when appropriate (medical provider, endocrinologist, pharmacist, social worker/ case management services, DSMES classes) (27)

Patient Education

Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support (DSMES)

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offer a Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support Toolkit on their website available to the public, designed for various health organizations/ community organizations and others interested in educating persons with diabetes to live a healthier lifestyle. Studies have shown that people who receive such education have better overall health and wellbeing. Despite these studies, a very low percentage of those qualified to receive such services access them. Check out the link below for more information.

- DSMES Program Review: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/dsmes/index.html

- DSMES Tooliit: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/dsmes-toolkit/index.html

Additional Resources

The following websites are being provided to assist the healthcare professional in accessing appropriate diabetes related information, including insulin coverage, food insecurities, food bank locations, and DSMES information. https://diabetes.org/

The American Diabetes Association provides information on prediabetes, Type 1, and Type 2 diabetes, as well as gestational diabetes. Included on their website are sections on medications, support groups, diet and activity, advocacy efforts, and prevention efforts. https://www.jdrf.org/

The Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation is a global organization for Type 1 diabetes mellitus. The site offers information on all things T1DM, including sections for those newly diagnosed, those interested in fundraising, research and clinical trials, daily diabetes management, volunteer opportunities, and access to local chapters worldwide. From the healthcare provider perspective, this website offers continuing education programs and pdf downloads for patient specific education. https://getinsulin.org/

The Get Insulin website provides information for persons with diabetes to access affordable insulin coverage. The site also offers information and guidance on health insurance plans, an insulin related newsletter, and external links to food sources (for patients with food insecurity issues) https://www.feedingamerica.org/find-your-local-foodbank

The Feeding America website enables persons with food insecurities to access food banks in their area, according to state location and zip code.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What community resources are available to your patients, post discharge, regarding access to food and medications?

- If your patient says they simply cannot afford their prescriptions, what is your current facility policy regarding this matter?

- How would you improve your current facility policy regarding patient access to medications for those uninsured/underinsured?

Patient Education and Follow-up Care (DSMES)

DSMES, or Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support, is the gold standard when it comes to patient education on this chronic medical condition. The goal of this education is to educate and empower the patient to successfully manage their medical condition, in efforts to lower the risk of long term, lifetime complications. DSMES is considered an ongoing process, and is recognized as an integral part of patient education at various critical points in their lifetime:

- At time of initial diagnosis

- During all patient medical appointments and routine follow-up care

- At time of onset for newly diagnosed complications

- Anytime a patient expresses concern over current diabetic management challenges.

Medicare and Medicaid

Medicare (Medicare Part B) and Medicaid plans currently offer the following coverage for diabetes related education (28):

- 10 hours of education (combined individual and group training) for an initial diagnosis of diabetes

- 2 hours of follow-up training annually after initial training completion

Qualifying Labs for DSMES

In general, a patient must be diagnosed with type 1, type 2, or gestational diabetes to qualify for DSMES, such as:

- Fasting Blood glucose of 126 mg/dL on 2 separate occasions

- 2-hour Post-Glucose Challenge of ≥200 mg/dL on 2 separate occasions

- Random Glucose Test of >200 mg/dL with symptoms of unmanaged diabetes

DSME Contents Overview

- Diabetes disease process pathophysiology and treatment to increase risk reduction for long term complications.

- Healthy eating includes meal planning, food label reading, carbohydrate counting, and strategies for eating out.

- Physical activity includes the benefits of activity as they related to better weight control, sleep habits and stress reduction.

- Medication usage overview to include medication administration, side effects, storage and cost issues.

- Blood glucose monitoring and management to include proper use of monitoring devices and associated equipment cleaning/repair.

- Prevention of complications (early detection, treatment, acute and chronic complications such as kidney disease and nerve damage; proper foot care)

- Healthy coping strategies to include stress reduction, effective self-management behaviors, and symptom recognition (hypoglycemia/hyperglycemia)

- Sick day management includes intake/output monitoring, over the counter medication usage, carbohydrate counting, ketone assessment, fever control and when to seek emergency services.

- Problem solving to include diabetes management during emergencies (power outages, flooding, tornados, hurricanes)

For more DSMES information visit: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/dsmes/dsmes-living-with-diabetes.html

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- With respect to DKA, what aspects of DSMES do you think are most important for patient education?

- How do you assess health literacy in your patients?

- What are some nursing interventions that could be done to assess a patient’s ability to correctly use a glucometer (glucose measuring device)?

- What community resources, post hospital discharge, are available for newly diagnosed patients with prediabetes/ type 2 diabetes in your area?

- What aspect of DSMES do you consider most important for ongoing sick day management education for your patients with diabetes?

Safety Considerations (Sick Day Management)

Successful management (prevention) of diabetic ketoacidosis requires patient education and empowerment in managing situations where glucose levels may be elevated and/or insulin levels (doses) are substandard (29).

There are many situations that can put a patient at risk for the development of DKA, including the following (29):

- Illness (acute and chronic), affecting normal food and fluid intake which negatively affects glucose management.

- Missed medication (insulin therapy) due to a clogged insulin pump tubing, a malfunctioning insulin pump, partial doses/skipped doses of insulin (whether related to costs, cognition, or mental health issues {diabetes distress}),

- Medication side effects

- Concurrent use of alcohol or drugs

- Physiologic stress (heart attack, stroke, physical injury)

Patient Education: Sick Day Management

Home treatment/ self-care (30)

The importance of preplanning cannot be understated. All persons with diabetes should have adequate supplies at home, to address an acute illness, including medications to treat basic symptoms before they escalate. These medications may include over the counter medications to treat pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, as well as adequate supplies to manage their diabetes (alcohol prep pads, syringes, prescription medications).

In addition, it is important to stock up on diabetic friendly foods and drinks to maintain nutrition and hydration levels during an acute illness. Such items might include sports drinks, soft drinks, instant cooked cereals, puddings, soups. In the event that a patient cannot eat their regular meals, the goal is to eat or drink 50 grams of carbohydrate every 4 hours to maintain glucose levels.

Sick Day Management Guidelines

- Monitor glucose levels every 4 hours.

- Stay hydrated – 4 to 6 ounces of fluid every ½ hour to prevent dehydration.

- Daily weight

- Temperature checks (rule out underlying infection)

- Current medication compliance- do not stop taking insulin or diabetic oral agents ** notify provider immediately if you choose to stop medications.

Seek emergency care for the following signs/ symptoms:

- Persistent vomiting/diarrhea to the point that you cannot tolerate any food or fluid intake for several hours

- Ongoing glucose levels above 240mg/dl

- The presence of moderate/high levels of ketones in urine

- Unexplained weight loss during an illness

- Any difficulty breathing

- Fruity/acetone smell on breath

- Changes in gait/balance/ vision

Research Findings

Research: Diabetes Distress and Burnout

Diabetes is a 24/7/365 chronic medical condition. Unlike many conditions that are simply managed with lifestyle changes or a single, once a day medication regimen, diabetes mellitus requires lifelong, around the clock commitment. Whether diet, activity, or medication management, a person with diabetes may easily feel overwhelmed by even the basic requirements for self-management. (31)

Ongoing health challenges, comorbid medical conditions, medication and diet cost issues and family dynamics can all affect a person’s ability to successfully manage any health condition. When emotions (sadness, anger, hostility, frustration, and even fear) become overwhelming, diabetic distress (a feeling of defeat) can often occur. Without prompt, patient specific interventions (mental health services, financial assistance, self-management education), these feeling will progress to diabetic burnout, and increase the risk of unhealthy habits (poor medication adherence and overall glycemic control). (32)

Diabetes distress can easily progress to diabetes burnout without appropriate ongoing medical treatment and mental health interventions. When a person with diabetes reaches the point of burnout, they often appear to disconnect from their routine healthcare, exhibiting indifference towards their overall health and well-being. They may become both mentally and physically exhausted from the daily requirements of this chronic medical condition. At this point, it is not uncommon to observe a person’s total disregard for their ongoing medical treatments, daily medications, routine self-care, and more. Missed medications, missed medical appointments, poor dietary intake, and a visible lack of basic hygienic practices are cause for concern.

A multidisciplinary approach to treating suspected diabetic distress and burnout is highly encouraged. From ongoing education, physical and mental health assessments, and enrollment in therapies (individual therapy sessions, and support groups), the person with diabetes needs a supportive environment in which to become empowered in the self-management of their disease progress. In doing so, it is believed that health outcomes are optimal, and the risk of long-term complications is lowered. (33)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Why do you think diabetes related distress occurs?

- What external factors affect a person’s ability to manage their diabetes successfully?

- What nursing education can you provide to possibly decrease the likelihood of diabetes distress?

- What areas of discharge planning/discharge instructions and follow-up care positively impact a person’s ability to manage their chronic medical condition?

Reserach: Diabulimia

Bulimia nervosa is a potentially life-threatening eating disorder characterized by episodic binge eating of large amounts of food, followed by forced vomiting and possibly laxative use to then “purge” the food. These alternating behaviors are the result of a person fearful of weight gain and willingness to lose weight in unhealthy ways. (34) (35)

Diabulimia is a serious, life threatening eating disorder affecting persons with Type 1 diabetes. Through intentional restricted/ limited use of prescribed insulin, weight loss occurs. This eating disorder is more common in young female adolescents and young adults. (34) (35)

Signs and symptoms may include the following (34) (35):

- Unexplained weight loss

- Hemoglobin A1C > 9

- Multiple episodes of DKA

- Unfilled insulin prescriptions, missed diabetes related medical appointments,

- Expressed fear of insulin related weight gain

- Anxiety related to body image

- Obsessive interest in calories and dieting

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How would you approach patient education with someone you suspect might be suffering from diabulimia?

- What might be some reasons for repeated DKA related incidents, unrelated to intentional restriction of insulin usage?

- How might you encourage a patient to improve compliance with routine medical appointments/ follow-up care?

- How would you respond to a patient’s concerning comment that “insulin is making me gain unwanted weight”?

- What consultations and referrals/resources would be appropriate for discharge planning of patients with suspected diabulimia?

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How would you approach patient education with someone you suspect might be suffering from diabulimia?

- What might be some reasons for repeated DKA related incidents, unrelated to intentional restriction of insulin usage?

- How might you encourage a patient to improve compliance with routine medical appointments/ follow-up care?

- How would you respond to a patient’s concerning comment that “insulin is making me gain unwanted weight”?

- What consultations and referrals/resources would be appropriate for discharge planning of patients with suspected diabulimia?

Research: Insulin Affordability

For many persons with diabetes, the perceived noncompliance with therapy (on behalf of the healthcare professional) is actually that of a cost related issue. Many persons cannot afford ongoing therapies related to management of this chronic medical condition. In attempts to “cut costs”, patients have admitted to skipping certain medications, cutting medications in half, reducing prescribed doses of insulin, and purchasing poorer quality, less expensive foods (that are often lacking in nutritional value). Poorly controlled / uncontrolled diabetes heightens the risk of both acute and chronic complications.

In an attempt to ensure accessibility and affordability of insulin therapy to persons with diabetes, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 in part ensures that persons with diabetes on Medicare pay no more than $35 for a month’s supply of insulin product under their prescription drug coverage. Similar drug coverage benefits were also extended to many state-based insurance plans. (36)

In addition, most Medicaid insurance plans, as well as private insurance companies have now enacted reduced insulin costs/ cost sharing programs. Finally, for patients with no insulin costs benefits, many national insurance providers offer free/ reduced cost insulin through their patient assistance program. For a comprehensive list of these resources, please see the following website link (American Diabetes Association): https://diabetes.org/tools-resources/affordable-insulin

Research: Insulin Delivery Systems

With the creation of advanced insulin delivery /monitoring devices (insulin pumps, and continuous glucose monitoring devices), the person with diabetes is afforded a more streamlined process to control their chronic medical condition. Most patients using such devices report better glucose control {“time in range”}, meaning the time their blood glucose levels remained in an acceptable range, ease of portability (of supplies), increased comfort (no more finger sticks), and decreased rates of anxiety, depression and distress.

The following website links represent various insulin delivery devices. Consider making a resource book containing various delivery devices for your specific unit (or hospital organization). Many have 24/7 customer service representatives available if you need to trouble shoot a device suspected of malfunctioning or require additional staff/patient educational resources.

This list contains a variety of websites but is not all inclusive. If you are caring for a patient with an insulin delivery device in place, please contact that specific company for more directions on its usage, removal, replacement parts and more.

Examples of insulin delivery devices:

- Makers of the MiniMed 780G System and the MiniMed 630G system: https://www.medtronic.com/us-en/healthcare-professionals/products/diabetes/insulin-pump-systems.html

- Makers of the Omnipod 5 and the Omnipod DASH Insulin Management System: https://www.omnipod.com/

- Quick overview of various insulin pumps currently on the market: https://consumerguide.diabetes.org/collections/pumps

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What is your facility’s current policy on patient admissions for DKA that want to wear their insulin pumps while in the hospital?

- Would you feel comfortable allowing a Type 1 diabetes patient, admitted for a medical condition unrelated to diabetes, to continue wearing their insulin pump during their hospital stay? Why/Why not?

Case Studies

Case Study #1