Course

Connecticut Domestic and Sexual Violence Training

Course Highlights

- In this Connecticut Domestic and Sexual Violence Training course, we will learn about the different forms of domestic abuse.

- You’ll also learn various demographic factors such as gender, age, race, and location in relation to risk of being a victim of abuse.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of ways that healthcare workers can have a larger impact on domestic violence by engaging in community involvement.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 3

Course By:

Sarah Schulze

MSN, APRN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

Each year, more than 10 million men and women in the United States experience physical abuse from an intimate partner. One in three women and one in four men have experienced some form of physical violence from an intimate partner in their lifetime and one in 10 women has been raped by an intimate partner (18). Such experiences have a lasting impact on physical and mental wellbeing, employment and economic status, effects on children who may witness such abuse, and, in severe cases, may even result in death.

Healthcare professionals are on the front lines of screening and prevention for domestic and sexual abuse and may be able to recognize early signs of abusive relationships, improve client connections to resources, and reduce the overall incidence of acute and long-term injury from abuse. This course aims to educate healthcare professionals on risk factors, signs of abuse, characteristics of abusers, and the role of healthcare in interrupting the abuse cycle.

Defining Domestic Abuse

The Department of Justice defines domestic violence, or intimate partner violence, as “a pattern of abusive behavior in any relationship that is used by one partner to gain or maintain power and control over another intimate partner.” Violence involving intimate partners accounts for 15% of all crime (18). There are various categories of abuse.

- Physical

Physically harming a partner by any manner, including hitting, slapping, shoving, etc. Can also involve denying medical care to someone in need as well as forcing drugs or alcohol use upon someone so as to alter their cognition.

- Sexual

Attempted or successful coercion to participate in sexual contact without consent. Includes rape (including within marriage), sexually demeaning, harming genitals, or forcing sexual acts after physical violence.

- Emotional

Patterns of chronic criticism, name-calling, or demeaning behaviors that damage a person’s self-worth.

- Economic

Use of coercion, fraud, or manipulation to restrict a person’s access to money, assets, or financial information. Or unethically acquiring and/or using someone’s economic resources through exploitation or improper conducting of power of attorney, guardianship, or conservatorship roles.

- Psychological

Threats or intimidation, forced isolation, destruction of property.

- Technological

Use of technology, such as online platforms, computers, mobile phones, cameras, apps, etc. to threaten, harm, control, harass, stalk, impersonate, or monitor another person (22).

Each of these categories has its own nuances and examples, but all consist of acts or threats that influence the weaker or subordinate partner. For the purpose of this course, we will mostly cover physical and sexual abuse, but all forms of abuse are valid and many times overlap with each other. Abusers use tactics such as (22):

- Intimidation

- Manipulation

- Humiliation

- Isolation

- Fear

- Coercion

- Blame

- Injuries/pain

Further information about the epidemiology of domestic violence will be covered below, but it is important to note that anyone can become a victim of domestic violence, including people of all races, ages, sexual orientations, and gender identities. People of all socioeconomic and education levels can be affected, and all types of relationships can be involved; including couples who are opposite-sex, same-sex, married, dating, co-parenting, or living together.

Affected individuals include not only the abused, but also family members (particularly children), coworkers, friends, and other members of the abused person’s community. Frequently witnessing domestic violence as a child increases the risk of becoming a victim of domestic abuse or an abuser in adulthood by demonstrating this as a “normal” way of life (22).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Which types of abuse do you think may be the most obvious or easy to identify?

- Which types are more subtle or difficult to identify?

- Before reviewing the epidemiology information in the following section, are there particular groups of people or characteristics that you think would be most susceptible to each type of abuse?

- What preconceived notions do you think might contribute to those opinions?

Epidemiology of Abuse

As discussed above, anyone can be a victim of domestic violence, however there are particular populations who are at an increased risk and more likely to be victimized. Awareness of these demographics is useful for healthcare professionals when trying to detect situations where abuse may be more likely. An overview of domestic violence prevalence for at-risk populations is discussed below.

Gender

Women are much more likely to be affected by domestic violence than men.

- 1 in 3 women has experienced some form of physical violence form an intimate partner, though the severity varies widely.

- 1 in 4 women has experienced severe intimate partner violence either of a physical or sexual nature, compared to 1 in 9 men.

- 1 in 7 women have experienced a physical injury from an intimate partner, as opposed to 1 in 25 men.

- 1 in 7 women has been stalked by a partner to a point where they feared harm; conversely 1 in 18 men have had this experience.

- 1 in 10 women have been raped by an intimate partner.

- 72% of all murder-suicides involve intimate partners and 94% of the victims of murder-suicides are women (18).

- Women are at risk for contraception coercion, where a partner pressures them to become pregnant or tampers with contraception to cause pregnancy (1).

Pregnant Women

Pregnant women are particularly vulnerable, and their risk of abuse is higher during this time, further complicating the health risks of abuse.

- 1 in 6 abused women is first abused during pregnancy

- Over 320,000 women experience domestic violence during pregnancy annually (14)

Ethnicity/Race

Minority race groups are more at risk for experiencing domestic violence. Department of Justice (DOJ) survey data indicates that 51.3% and 17.7% of white women report having experienced physical and sexual violence respectively, while non-white women report experiencing these at 54% and 19.8% respectively (26).

Among minorities, American Indian and Alaskan Natives are among the most at risk. This group experiences high poverty rates, particularly on reservations, increased drug and alcohol use, and minimal resources for Natives seeking culturally specific shelter or safety from abuse, all of which increases the risk and prevalence of domestic violence, particularly among Native women (26)

- Over 84% of Native women experience some form of violence during their life

- American Indians are 3 times more likely to be a victim of sexual violence than all other ethnic groups

- 55.5% of Native women experience domestic violence in their lifetime

- 66.6% experience psychological abuse from a partner

- Over half have experienced sexual assault (26)

For the Black community, factors like racist societal and legal structures have created gaps in economic opportunities, education, access to healthcare, and access to safety/resources that puts Black men and women at higher risk of domestic violence than their white peers. Due to stereotypes and inconsistent cultural competence among law enforcement, jurors, and judges, Black victims of abuse are more likely to be arrested and less likely to be believed by the legal system than white victims (13).

- 45.1% of Black women and 40.1% of Black men experience domestic violence of a physical or sexual nature in their lifetimes

- 53.8% of Black women and 56.1% of Black men have been victims of psychological abuse in their lifetime

- 8.8% of Black women have been raped by a partner in their lifetime

- Homicide involving domestic partners was highest among Black women in 2017, at 2.5 per 100,000 (16)

Age

Opposing ends of the age spectrum are both at increased risk of victimization, with teens and young adults as well as elderly people being at higher risk than the rest of the population.

Teens are at an increased risk due to their inexperience with dating and relationships and susceptibility to peer pressure. They may also feel hesitant to tell an adult about abuse for fear of consequences or punishment. They may not recognize behaviors as abusive right away and may perceive controlling or jealous behaviors as signs of love. Teens who have witnessed repeated domestic violence among parents or other family members may also believe that this is how normal relationships function.

According to 2023 data, one in 12 high school students report physical violence and one in 12 report sexual violence in a dating relationship (5).

- 1.5 million high school students are abused in a dating relationship annually (only 33% ever tell anyone about it)

- 26% of teens are victims of cyber dating abuse; female teens were twice as likely to experience this as male teens

- 57% of teens report knowing someone who has been physically, sexually, or verbally abused in a relationship (19)

Older adults are also at an increased risk, often due to impaired physical or cognitive abilities that require them to rely on a caretaker. They may be isolated, with limited social support or without the ability to tell someone what is happening to them.

- It is estimated more than 10% of older adults who live in communities experience physical, psychological, sexual, or financial abuse from a caretaker

- Only about 1 in 14 of these incidents are reported

- A spouse or intimate partner is the perpetrator in 57% of physical abuse, 87% of psychological abuse, and 40% of sexual abuse cases

- 39% of firearm homicides involving older adults were committed by a domestic partner (21)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Why do you think pregnancy puts women at an increased risk of being a victim of domestic violence?

- Think of an elderly client you have cared for before. How easy do you think it would be for a caregiver to take advantage of them?

- Are there other clients of the same age who might be more or less susceptible to this risk?

- What factors do you think affect the level of risk for elderly clients?

LGBTQ Community

Though it is well-known that members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer (LGBTQ) community are at increased risk of violence or harm. In the general population, awareness of domestic violence rates for the LGBTQ community is just beginning to rise, as most existing data is based on heterosexual relationships. Emerging data is revealing that people in the LGBTQ community experience domestic violence at equal or greater rates than their straight and cis-gender peers (20).

*Note: A basic understanding of sex, gender, and sexual orientation is necessary when caring for members of the LGTBQ community so as to offer comprehensive and competent care. These common terms and their definitions are included below for anyone needing clarification.

Quick Terminology Lesson

Sex: A label, typically of male or female, assigned at birth, based on the genitals or chromosomes of a person. Sometimes the label is “intersex” when genitals or chromosomes do not fit into the typical categories of male and female. This is static throughout life, though surgery or medications can attempt to alter physical characteristics related to sex.

Gender: Gender is more nuanced than sex and is related to socially constructed expectations about appearance, behavior, characteristics based on gender. Gender identity is how a person feels about themselves internally and how this matches (or does not match) the sex they were assigned at birth. Gender identity is not related to who a person finds physically or sexually attractive. Gender identity is on a spectrum and does not have to be purely feminine or masculine and can also be fluid and change throughout a person's life.

- Cis-gender: When a person identifies with the sex they were assigned at birth and feels innately feminine or masculine.

- Transgender: When a person identifies with the opposite sex they were assigned at birth. This can lead to gender dysphoria or feeling distressed and uncomfortable when conforming with expected gender appearances, roles, or behaviors.

- Nonbinary: When a person does not feel innately or overwhelming feminine or masculine. A nonbinary person can identify with some aspects of both male and female genders or reject both entirely.

Sexual orientation: A person’s identity in relation to who they are attracted to romantically, physically, and/or sexually. This can be fluid and change over time, so do not assume a client has always or will always identify with the same sexual orientation throughout their life.

Types of sexual orientation include:

- -Heterosexual/Straight: Being attracted to the opposite sex or gender as oneself

- -Homosexual/Gay/Lesbian: Being attracted to the same sex or gender as oneself.

- -Bisexual: Being attracted to both the same and opposite sex or gender as oneself

- -Pansexual: Being attracted to any person across the gender spectrum, including non-binary people

(11)

There are elements of domestic violence that are specific to the LGBTQ community. One example is “outing” or threatening to disclose a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity without their consent. Threatening to out someone can be used as leverage or a power dynamic in psychological abuse, and actually outing someone can lead to an increased risk of rejection and physical or sexual harm depending on who the information is revealed to.

Additionally, members of the LGBTQ community may be afraid to seek help in abusive situations or may even experience discrimination when they do seek help, putting them at greater risk of significant harm. Poorly trained staff, implicit biases of staff, and even gender-specific resources such as women’s shelters can be difficult to navigate for LGBTQ victims (20). Statistics about domestic violence in LBGTQ relationships include the following:

- 61.1% of bisexual women and 43.8% of lesbian women report experiencing rape, physical violence, or stalking by a domestic partner at some point in their life; compared to 35% of heterosexual women

- 37.3% of bisexual men and 26% of gay men report experiencing rape, physical violence, or stalking by a domestic partner at some point in their life; compared to 29% of heterosexual men

- 26% reported experiences of near-lethal violence in male-male relationships

- Fewer than 5% of all LGBTQ domestic violence victims seek orders of protection

- Transgender people are more likely to experience domestic violence in a public setting compared to cis-gender individuals

- Transgender individuals experience unique forms of psychological/emotional abuse such as being called “it” or being ridiculed for physical appearance

- Bisexual individuals are more likely to experience sexual violence than other sexual orientations

- Black LGBTQ individuals are more likely to experience physical violence from a partner than other races

- White LGBTQ individuals are more likely to experience sexual violence from a partner than other races (20)

Disabled Populations

Nearly a quarter of all U.S. adults have some type of physical, cognitive, or emotional disability. People with disabilities are particularly vulnerable to domestic violence.

- Nearly 70% of people who have a disability experience domestic abuse

- People who have a disability are three times as likely to be sexually assaulted than their non-disabled peers (23)

People with disabilities relying at least partially on others to function in their daily life are particularly vulnerable to being intimidated, isolated, or controlled by someone they trust (power imbalance). Some 75% to 80% of domestic abuse of people with a physical disability and 95% of abuse of those with a cognitive disability goes unreported. The types of abuse are often unique to the disability as well, including:

- Invalidation or minimization of disability

- Shaming or ridiculing for disability

- Refusal to help with daily tasks such as bathing, dressing, or eating

- Over or under medicating

- Sexual acts without consent

- Denying access to healthcare services/appointments or medications

- Limiting access to mobility devices such as walkers, wheelchairs, or prosthetics

- Withholding finances

- Threatening abandonment (23)

Certain populations with disabilities are more at risk than others.

- Women who have a disability:

-

- 80% of women who have a disability report sexual assault

- 40% higher rates of domestic abuse

- Violence experienced by women with disabilities may be more frequent or of greater severity

- More likely to experience reproductive coercion, stalking, or psychological abuse

- People in the LGBTQ community who have a disability:

-

- LGBTQ facilities may not be accessible for those with disabilities

- Disability services may not be competent with issues of the LGBTQ community

- Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) with disabilities:

-

- Increased risk for police brutality

- Half of Black people with disabilities have been arrested at least once by age 28

- Half of people killed by law enforcement have disabilities (23)

Geographic Location

A person’s location also plays a role in the risk of domestic violence, with rural locations and homelessness increasing the risk.

Twenty percent of U.S. residents live in a rural location (17). Unique characteristics of rural living increase the prevalence and severity of domestic violence in the following three ways.

Geographic Isolation

- 80% of rural counties do not have a domestic violence program

- >25% of rural communities are more than 40 miles from the nearest domestic violence program

- Rural communities lack robust public transportation, and many people are without a car

- Decreased likelihood that a neighbor or community member will see or hear abuse occurring

- Significantly increased time needed for first responders to arrive after an emergency call

- Scarcity of housing options, especially of lower cost, make it difficult to leave (17)

Social/Cultural Barriers

- Rural regions are often more conservative with traditional gender roles (physical or sexual violence against women may be viewed as “normal”)

- Physical and sexual violence or assault may be viewed as private matters not to be discussed outside of the home

- Friends or family may encourage victims to stay in abusive relationships to avoid divorce or for children

- Women may be shamed or not believed for reporting abuse

- Small-town gossip or lack of anonymity may keep victims from pressing charges or seeking assistive services

- Women may be less likely to have a job or financial independence from their partners (17)

Poor or Impartial Criminal Justice Response

- Domestic violence may be seen as commonplace and low priority among law enforcement

- Law enforcement, prosecutors, or judges may have relationships with perpetrators or their families that impede their ability to be impartial

- Law enforcement may hold a patriarchal sense of loyalty to other men and put that above the safety of women in the community (“Good ol’ boys club” attitude) (17)

Due to geographic isolation and lack of resources, as well as potential lack of income or financial independence, many victims in rural locations wind up homeless if they leave an abusive relationship. This comes with its own significant struggles and risks and is often not sustainable, leading the victims back to live with their perpetrators rather than continue being homeless, essentially creating a vicious cycle between homelessness and abuse.

- A 2003 survey revealed 46% of homeless women reported being a victim of physical or sexual abuse in the last year.

- In 2005, 50% of U.S. cities cited domestic violence as a leading cause of homelessness.

- Some landlords have a zero-tolerance policy for domestic violence and will either evict or refuse to rent in the first place to victims of domestic violence. This was as high as 28% in a survey in New York City (27)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Think of the type of geographic area you work in. What types of resources are available and how long would it take to get there?

- Is public transportation available to take clients there?

- If you had a client who was physically assaulted, how likely would neighbors be to hear or see the incident?

- How long would it take emergency services to get there if your client called 911?

- Now think about how those factors might differ in a location very different from your own

Socioeconomic Status and Education Level

Though people of any socioeconomic status are susceptible to domestic abuse, those with a low socioeconomic status or education level are at an increased risk. This is in part due to the increased isolation and lack of available resources to people in poverty or with low education. Particularly, women who do not work outside of the home or do not have any professional skills with which to get a job are at risk of being more easily isolated or kept from utilizing resources. Those with lower education levels are also more likely to view physical or sexual violence within a relationship as “normal” and tolerate the abuse without attempting to leave.

Women with household incomes below $75,000 annually are seven times more likely to experience physical or sexual violence than women whose household incomes are above $75,000 (27).

There is also a circular relationship between low socioeconomic status and domestic violence, as victims of abuse are both more likely to be poor and also more likely to experience economic loss or financial insecurity due to the abuse. Access to money or work can also be restricted by the abuse as part of the attempt to maintain power and control.

- Between 21-60% of abuse victims lose their jobs from abuse-related reasons (missing work, distracted or poor job performance, etc.)

- Domestic abuse victims lose a combined eight million days of paid work annually due to injuries or home conflict (18).

Immigrants, in particular, may be affected by this as they may be of lower education (or at least unable to fluently speak the language of the new country), often poor or without any assets, and may be unable to work or earn money. They may rely on an abusive partner for money, a place to live, and even communication, keeping them isolated in a relationship that feeds on control/power (25).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Are there any of the above statistics or risk factors that surprised you?

- Do you think any of the above information might change your awareness of potential abuse situations?

- Think of a time when you cared for someone at an increased risk of abuse. Do you think you were aware of the risk or were you on the lookout for signs of abuse?

- If you have cared for known victims of abuse, what risk factors did they have?

Health Implications of Abuse

There are many health implications for people in abusive relationships. Acute or short-term injuries are typically physical in nature and include things like (9):

- Cuts

- Bruises

- Broken bones

- Concussions

- Burns

Additionally, only 34% of people who sustained a physical injury from domestic violence sought medical care for those injuries, meaning many may have poorly healed injuries or long-term sequelae from lack of proper treatment (18).

There are also long-term consequences or chronic health conditions that result from domestic violence, including:

- HIV or other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) from sexual abuse

- Bladder and kidney infections

- Circulatory/cardiovascular conditions

- Asthma

- Unintended pregnancy, including teenage pregnancy

- Chronic pain

- Arthritis or joint disorders

- Gastrointestinal disorders or nutritional deficiencies

- Neurological disorders including migraines and neuropathy

- Sexual dysfunction (9)

Mental health effects are also significant with victims experiencing increased rates of:

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Suicidal thoughts and attempts

- Addiction to drugs or alcohol (9)

Certain populations, such as individuals in the LGBTQ community, are already at an increased risk for mental health issues and suicidal ideations. Therefore, abused members of this population are at a further increased risk.

Additionally, victims of abuse may experience social or economic consequences that in turn worsen their overall health through poorer living conditions, nutrition, and access to healthcare. Economic consequences include (9):

- Interrupted or lost educational opportunities

- Lost professional opportunities

- Damage or destruction to property or items of value

- Medical or legal debt

Health implications may be dependent on age or situation as well. Among the unique risks are pregnant, very young, and very old victims.

Abuse during pregnancy can result in intrauterine hemorrhage, preterm labor, or miscarriage. Chronic stress during pregnancy, lack of prenatal care, or trauma to the fetus can lead to long-term health effects of the infant once born (14). Some women may also be victims of contraceptive or reproductive coercion, where an abuser pressures them to become pregnant or tampers with their contraception to cause pregnancy. Unwanted pregnancy puts these women into a more vulnerable position to be victims of abuse and the above complications (1).

Surveys of youth show that 50% of teens and young adults who have experienced dating violence or rape have also attempted suicide compared to 12.5% of youths without a history of abuse (19). Domestic violence also increases the risk of pregnancy and STIs which can have a more extreme and lasting impact on teens, affecting reproductive or sexual health for the rest of their lives.

For older adults, the risks are increased as well, with elderly victims of abuse having a shorter lifespan than their peers who are not abused. Mental health effects such as depression, anxiety, fear, isolation, loss of self-esteem, and feelings of shame, powerlessness, and hopelessness may be exacerbated because people in this age group are already struggling with a lack of independence or isolation from a social network. Overall, this can reduce quality of life and dignity in an already difficult period of decline (21).

Exposure to domestic violence, even when not directly victimized, also has a lasting impact on health. Children are particularly vulnerable to witnessing or being exposed to abuse:

- 1 in 15 children are a witness to domestic violence during childhood (of those, nearly 60% experience maltreatment themselves).

- Homes with both child maltreatment and intimate partner violence often have more severe levels of abuse.

- 1 in 5 child homicides between ages 2-14 are related to domestic violence cases (15).

Children who are exposed to domestic violence may experience acute symptoms such as:

- Anxiety

- Aggression

- Sleep disruption

- Nightmares

- Bedwetting

- Concentration deficits or poor school performance

Over time, children who are exposed to domestic violence are:

- 3 times as likely to engage in violent behavior as their peers

- More likely to be either perpetrators or victims in their own future relationships

- At greater risk of health conditions like obesity, cancer, cardiovascular disease, substance abuse, depression, and unintentional pregnancy (15)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever cared for an acute victim of physical or sexual violence?

- What types of injuries did they have and how might those injuries have healed differently if the client had not sought care?

- To your knowledge, have you cared for any clients with long-term sequelae of abuse?

- How do you think coping with a chronic illness sustained from violence might be different from coping with a chronic illness not sustained from violence?

Perpetrators of Abuse

It is important for healthcare professionals to not only recognize risk factors for victims of abuse, but also risks for becoming a perpetrator of abuse. Truly mitigating risks and reducing the prevalence of domestic abuse requires recognizing and offering services to victims, but also identifying potential abusers and providing interventions to stop abuse at the source.

Risk Factors

The conditions that lead to perpetrators becoming abusers are nuanced and multifaceted, involving individual experiences, past relationships, attitudes of the person’s community, and societal implications (4).

Individual

Individual risk factors are based on lived experiences, existing mental health conditions, and individual stressors. Individual risk factors include:

- Poor self esteem

- Low education level

- Young age

- Problem behaviors in youth

- Drug or alcohol abuse

- Depression or anxiety

- Poor coping or problem-solving skills

- Poor impulse control

- Personality disorders

- Isolation or few friends, small support network

- Economic stress such as unemployment or low income

- Hostile/misogynistic attitudes towards women and strict gender role of male dominance

- Being physically or emotionally abused as a child

Relationship

Relationship risk factors are based on the characteristics of the people involved in the relationship and their attitudes and behaviors within the relationship. Relationship risk factors include:

- Relationships with frequent jealousy, possessiveness, tension, or divorces and separation

- One partner with clear dominance or control the majority of the time

- Families undergoing economic stress or low income

- Network of peers in aggressive or violent relationships

- Parents with low education levels

- Witnessing violence between parents during childhood

Community

Community risk factors are based on the attitudes and social norms of people in the neighborhoods, workplace, or schools a person is involved in. Community risk factors include:

- High poverty and low education rates

- High unemployment rates

- High crime/violence rates

- High drug use

- Low sense of community among neighbors

Societal

Societal risk factors are based on the attitudes and political policies where a person lives on a broader scale, including city and state level. Societal risk factors include (4):

- Emphasis on traditional gender roles (women at home/unemployed/submissive, men work and make family decisions)

- Cultural norms of aggression

- Weak education, health, and social policies or support

Protective Factors

There are some factors that are protective against becoming a perpetrator of abuse, even for people who may have grown up around domestic abuse. Protective factors include (4):

- A strong social support network

- Exposure to strong, positive relationships

- An involved and neighborly community

- Available services and resources within a person’s community

- Access to stable and safe housing

- Access to medical and mental health care

The Cycle of Abuse

In addition to recognizing who may become or be an abuser, it is important to understand and recognize the pattern or cycle of abuse and how perpetrators maintain control in the relationship. While each abuse scenario is unique, the overall patterns are the same and exist in a cycle which may progress quickly or over longer stretches of time. The four main stages are tension, incident, reconciliation, and calm (10).

Tension Phase

During the tension phase, there is a slow increase in the frequency and intensity of irritability, short temper, emotional outbursts, and impatience. There may be external factors such as life stressors, financial strain, work struggles, etc. that make the abuser feel out of control, adding to this rising tension. Victims may report “walking on eggshells” during this time, as they feel the tension build (10).

Incident Phase

Once the tension builds to a breaking point, one or more abusive incidents will occur. Abuse perpetrators do not have an “anger problem” as they are able to control their emotions in places like work, school, or in public. The anger and aggression displayed by a perpetrator is an intentional use of power to regain or maintain control over the weaker partner in the relationship. Incidents can look like (10):

- Intimidation

- Threats

- Physical violence

- Sexual violence

- Verbal violence (insults, name calling)

- Shaming/humiliation

- Blaming

- Social isolation

- Manipulation

- Financial abuse

- Emotional abandonment

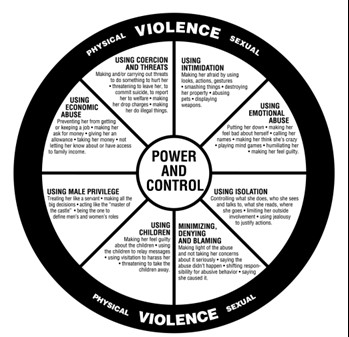

Abusers can use many methods of violence and a variety of tactics within each of those methods. The ultimate goal of all behaviors is to maintain control over the victim and remain in a position of power. Figure 1 below provides examples of specific behaviors within each type of violence.

Figure 1. Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs (3)

Reconciliation Phase

Once the incident is over, the perpetrator feels a relief of tension, though the victim likely is at peak anxiety. The abuser may seem to show remorse in the form of apologies, affection, or promises to never become violent again. Victims are often willing to give abusers another chance during this stage because they seem to show genuine remorse or intent to reform (10).

Calm Phase

Next the relationship moves into a calm phase where the perpetrator’s remorse dissipates, and they may begin to dismiss the incident by shifting blame or saying things like “it wasn’t really that bad.” For the victim, this can be confusing or feel like a letdown when the abuser’s previous intent to make changes fades. This eventually shifts back into rising tension and the cycle repeats itself (10).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Think about the population you work with. Consider who might be at risk for being a victim of abuse but also think about what risk factors you’ve encountered for your clients becoming a perpetrator of abuse.

- What are the community or societal factors in your region that might increase the risk of becoming a perpetrator?

- Think about the abuse cycle and consider why victims may choose to stay in a violent relationship.

- At what point in the abuse cycle do you think healthcare professionals are most likely to encounter victims of abuse or pick up on abuse red flags?

Role of the Healthcare Professional in Abuse

Given all of this knowledge about who is at risk and what goes on in an abusive relationship, you may be wondering how healthcare professionals can help or what your role entails. The responsibility of the healthcare professional lies in a few main areas of identifying and handling abuse situations.

Risk Identification

One of the first steps in disrupting the abuse cycle is identifying those most at risk. Part of this is through knowledge of risk factors and vulnerable populations and signs of abuse, as already covered in this course. Another means of identification is through routine screening of certain populations. Unfortunately, there is a limited number of screening tools available, and tools are almost exclusively targeted at women of reproductive age. Available tools assess for domestic abuse within the last year; there is no recommended appropriate interval to administer screening and it is at the provider’s discretion, though at least annually is typical (24). Some examples of available screening tools include:

- HARK (Humiliation, Afraid, Rape, Kick): A four-question tool that assesses emotional and physical violence

- HITS (Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream): A four-item tool that assesses the frequency of domestic violence

- E-HITS (Extended version of HITS): Includes an additional question to assess the frequency of sexual violence

- PVS (Partner Violence Screen): A three-item tool that assesses physical abuse and safety

- WAST (Women Abuse Screening Tool): An eight-item tool that assesses physical and emotional abuse from domestic partner (24)

The above screening tools are well studied in women and have been shown to be effective. Currently, there is a lack of studied and effective domestic violence screening tools in the primary care setting, especially for teens, men, clients in the LGBTQ community, and the elderly. More work is needed in this area. Even for women, screening is not often conducted outside of the obstetrics/gynecology (OB/GYN) setting (24).

Simply asking “Do you feel safe at home?” or “Is there any history of violence in your home?” is also a basic way to cast a wide net among large volumes of patients and reduce the chance of domestic violence going unnoticed. Asking questions like these on admission in the emergency department (ED) or hospital, or during the intake process for office visits can easily be implemented as part of facility policy. Many offices or hospitals will also have signs up in bathrooms, changing areas, or exam rooms that encourage clients to disclose abuse in a confidential and safe way during their visit (24).

Screenings of any kind are most effective when the client is separated from their partner, even briefly. If the abuser is with them, they can be asked to step into the waiting room or, if it is necessary to be more subtle, clients can be asked to leave the room for something inconspicuous, like providing a urine sample, and then lead to a separate room for further, private discussion (24).

Appropriate Response

Timely referral to appropriate ongoing services has been shown to reduce physical and mental harm from violence and abuse. When domestic violence has been disclosed or a screening has come back positive, the attitudes and behaviors of the healthcare professional are important and can have a big impact on the client’s feelings about their care. Appropriate and sensitive behaviors include:

- Listening to clients actively and objectively

- Believing the client

- Validating the client’s feelings and fears

- Avoiding asking “why” questions or placing blame like “Why didn’t you call the police?” or “Why do you stay?”

- Respecting a client’s decision to stay or leave

Plan of Action

Interventions and next steps include (6):

Gathering Additional Information

- Getting a detailed history

- Assessing symptoms

- Taking photographs if necessary (bruise patterns, burns, cuts, etc.)

Assessing Safety

- Verbal/physical threats

- Weapons in the home

- Frequency of violence

- Children or others in the home

Develop a safety plan together with client

- Signs of rising tension

- Who to call or where to go

- Available resources in community

Provide referrals as desired by client

- Police (for order of protection or to press charges)

- Hotlines

- Shelters

- Counseling

Documentation and Reporting

Appropriate documentation of abuse, including detailed history, exam, and any pictures, as well as a safety plan and any resource connection should be included in the client’s chart. Laws about mandated reporting vary by state and healthcare professionals may need to report the documented abuse to authorities.

In Connecticut, there is no requirement to report domestic violence or abuse. Mandated reporting is reserved for abuse of children, disabled people, residents of long term care facilities, the elderly, and healthcare professionals who are impaired or negligent (8).

For situations which must be reported, the report must be made within 12 hours of when a clinician first suspects abuse or becomes aware of an abuse situation. Reports may be made through the Connecticut State Department of Public Health which has various resources and care lines depending on the type of suspected abuse being reported. Examples can be found in the table below (8).

|

Category of Abuse Victim |

Resource for Reporting |

|

Children |

Department of Children and Families (DCF) Child Abuse and Neglect Careline |

|

Disabled person |

Office of Protection and Advocacy for Persons with Disabilities |

|

Residents of long term care facilities |

Commissioner of Social Services |

|

Elderly |

Commissioner of Social Services |

|

Impaired clinicians |

Connecticut Department of Public Health |

If you are required to report an incident, it is best to notify the client prior to reporting so that they are aware and prepared and can utilize their safety plan if they feel this will anger the perpetrator (6).

Counseling/Therapy

When considering counseling, individual therapy is always recommended and beneficial, but it is important to note couples therapy may be contraindicated. If the goal is to maintain the relationship and address abuse cycles, couples therapy should be approached cautiously as this type of treatment may increase the abusive behaviors. Couples therapy may elicit a different viewpoint or information about the relationship that threatens the abuser's desire for control and may increase anger, minimization of abuse, or victim blaming as the abuser now has to work harder to maintain control. This can increase abusive behaviors outside of therapy sessions and put the victim at greater risk.

There is some evidence to suggest couples therapy can be helpful in breaking abuse cycles, but it should only be undergone with an experienced therapist with special knowledge of how to identify and address abuse in a manner that does not exacerbate the abuse (12 ).

Follow Up

Often domestic violence reoccurs and increases in frequency or intensity over time. Up to 75% of clients reporting domestic violence will continue to experience abuse. This can be frustrating for healthcare professionals, but it is important to remember that your role is to document the abuse, provide resources to clients, report when required, and not judge or verbalize opinions on what clients should do (2).

Appropriate follow up for healing wounds or injuries should be scheduled. Information about local domestic violence resources should be provided at each visit with clients. If a client does leave an abusive relationship, it is important to continue screening for violence as they may return to the relationship and are at an increased risk of entering new relationships that are also abusive (2).

Community Outreach

Healthcare professionals can have an impact on domestic violence in broader ways that direct client interactions as well. Advocacy on a community level can help increase awareness, shift harmful societal views on domestic violence, and create more robust community resources. Places where healthcare voices can help shift the narrative on domestic violence include (6):

- Parent Teacher Association (PTA) members

- Church members

- Community leadership positions

- Social clubs

- Political/voter groups

- Connecticut Coalition Against Domestic Violence (CCADV)

Nursing Education

RNs with a Connecticut license must apply for renewal every 6 years. They are not required to obtain CEUs specific to domestic or sexual violence for license renewal, though the topic is strongly recommended as these issues can impact clients across a variety of demographics and in many different healthcare settings. Required topics for license renewal include screening for PTSD, depression, and risk of suicide, and training for suicide prevention (7).

Connecticut APRNs must complete 50 hours of continuing education every 2 years and are required to complete at least 1 hour each on the topics of sexual assault and domestic violence. Having compassionate, knowledgeable, and competently prepared providers in delicate situations such as abuse, or violence can increase client safety and improve overall health outcomes (7).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What tools or processes does your current facility use to screen for abuse?

- How could your facility improve on those screening practices?

- If your facility does encounter someone who discloses abuse, what processes are in place for next steps of reporting and connecting with resources?

Case Studies

Kimari’s Case

Kimari is a Black, 22-year-old pregnant woman who presents to the OB clinic for a second trimester visit with complaints of abdominal pain. Kimari’s partner accompanies her to the visit today and the nurse notes that Kimari is unusually quiet and withdrawn compared to her previous visits. Her partner is answering most of the nurse’s questions for her. The nurse asks him to step into the waiting room so Kimari can change into a gown. Once he is gone, the nurse administers the HITS screening tool and opens a discussion with the client. Kimari reveals that her partner had been emotionally abusive in the past but never physically. However, since she has become pregnant, the abuse has worsened and has started to include forced sexual activity and physical violence. She admits her abdominal pain today is due to him shoving her down the stairs in the house the day before.

The nurse sits with Kimari and listens to her description of the events of the last few weeks. At this time, she wants to stay in the relationship as she does not have anywhere else to go and also has a two-year-old at home to think about. She is interested in individual counseling and develops a safety plan with the nurse which includes hotlines and local resources, as well as a plan to go to her sister’s house if tension seems to be rising again.

A physical exam reveals a healthy pregnancy with normally developing fetus and no complications from the fall down the stairs. The information from today’s visit is documented in her record and a follow-up appointment is scheduled for the following month.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What risk factors does this client have for being a victim of abuse?

- What potential complications can occur during pregnancy due to physical violence?

- What interventions did the nurse utilize appropriately when handling Kimari’s case?

- How do you feel about the outcome of this case? Do you have preconceived ideas about how this case should be handled that you would need to adjust in order to provide sensitive care like this nurse did?

Kevin’s Case

Kevin is a 28-year-old gay man presenting to the family practice clinic for an annual wellness visit. Kevin’s provider conducts a thorough physical assessment, orders labs, and administers screening tools for anxiety and depression. Kevin is found to be in good health but does score moderately high on his depression screening. The provider caring for him recommends individual counseling and offers an antidepressant which Kevin accepts. He is scheduled for a follow up in one month and the visit concludes.

Kevin returns home where he lives with an emotionally abusive husband. When Kevin reveals that he was given a prescription for an antidepressant, his husband ridicules him and calls him “crazy” and “weak.” They get into an argument and Kevin’s husband slaps him.

Later that evening, Kevin’s husband finds him unresponsive but still breathing in the bathroom with what appears to be an attempted overdose. He calls 911.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What risk factors does this client have for being a victim of abuse?

- What risk factors does this client have for suicidal thoughts or actions?

- How could this case have been handled differently?

- Without standard screening tools for domestic violence in LGBTQ relationships, how could Kevin’s provider have assessed for safety within his relationship?

Conclusion

Domestic violence, particularly physical and sexual abuse, is a problem with far-reaching consequences that affects people of all demographics. Identification of those most at risk, early intervention, and connection to resources, as well as prompt treatment of acute injuries and health implications are all important components in reducing the tragic impact of domestic violence. Healthcare professionals in all settings may encounter abuse situations and should be up to date on best practices for screening and management of these cases. Hopefully upon completion of this course, healthcare professionals will feel confident in their role in supporting victims.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever reported an abuse situation? If so, what was the process like? Did you find it effective or have concerns?

- What community involvement opportunities exist in your community that can have an impact on domestic violence resources?

References + Disclaimer

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. (2022). Reproductive and sexual coercion. Retrieved from: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2013/02/reproductive-and-sexual-coercion#:~:text=Reproductive%20coercion%20is%20related%20to,pregnancy%20coercion%2C%20and%20pregnancy%20pressure.

- Burnett, L. B. (2018, July). Domestic violence follow up. Emergency Medicine. Retrieved from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/805546-overview?form=fpf

- Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs. (n.d.). Power and control wheel. NCADV. Retrieved from: https://www.theduluthmodel.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/PowerandControl.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, November). Risk and protective factors for perpetration. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/riskprotectivefactors.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, January). Fast fact: preventing teen dating violence. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/teendatingviolence/fastfact.html

- Connecticut Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (2024). https://www.ctcadv.org/

- Connecticut State Department of Public Health. (n.d.). Continuing education. DPH. https://portal.ct.gov/DPH/Practitioner-Licensing–Investigations/Registered-Nurse/Continuing-Education

- Connecticut State Department of Public Health. (n.d.). Mandatory reporters of abuse, neglect, exploitation, and impaired practitioners. DPH. https://portal.ct.gov/DPH/Practitioner-Licensing–Investigations/PLIS/Mandatory-Reporters-of-Abuse-Neglect-Exploitation-and-Impaired-Practitioners

- Connections for Abused Women and Their Children. (2023, February). The impact of domestic violence. Retrieved from: https://www.cawc.org/news/the-impact-of-domestic-violence/?gclid=Cj0KCQjwiIOmBhDjARIsAP6YhSWPF8eUFB4f_OF2oy4w6YdyGheawOkX8Heh_hvOCPT-Wg3vp9bICeIaAkH5EALw_wcB

- Gillette, H. (2022). The 4 stages of the cycle of abuse: from tension to calm and back. Retrieved from: https://psychcentral.com/health/cycle-of-abuse

- GLAAD. N.d. Glossary of terms: LGBTQ. Retrieved from: https://www.glaad.org/reference/terms

- Karakurt, G., Whiting, K., van Esch, C., Bolen, S. D., & Calabrese, J. R. (2016). Couples Therapy for Intimate Partner Violence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of marital and family therapy, 42(4), 567–583. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12178

- Lantz, B., Wenger, M. R., & Craig, C. J. (2023). What If They Were White? The Differential Arrest Consequences of Victim Characteristics for Black and White Co-offenders. Social problems, 70(2), 297–320. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spab043

- March of Dimes. (n.d.). Abuse during pregnancy. Retrieved from: https://www.marchofdimes.org/find-support/topics/pregnancy/abuse-during-pregnancy#:~:text=Unfortunately%2C%20some%20women%20experience%20abuse,is%20first%20abused%20during%20pregnancy.

- National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (n.d.). Domestic violence and children. NCADV. Retrieved from: https://assets.speakcdn.com/assets/2497/dv_and_children.pdf

- National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (n.d.a,). Domestic violence and the black community. NCADV. Retrieved from: https://assets.speakcdn.com/assets/2497/dv_in_the_black_community.pdf

- National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (n.d.). Gender based violence in rural communities. NCADV. Retrieved from: https://assets.speakcdn.com/assets/2497/ncadv_fact_sheet_-_gbv_in_rural_communities.pdf

- National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (n.d.b.). National statistics. NCADV. Retrieved from: https://ncadv.org/STATISTICS

- National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (n.d.c.). Teen, campus, and dating violence. NCADV. Retrieved from:https://assets.speakcdn.com/assets/2497/dating_abuse_and_teen_violence_ncadv.pdf

- National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (2018). Domestic violence and the LGBTQ community. NCADV. Retrieved from: https://ncadv.org/blog/posts/domestic-violence-and-the-lgbtq-community

- National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (2022). Abuse in later life. NCADV. Retrieved from: https://assets.speakcdn.com/assets/2497/abuse_in_later_life.pdf

- Office of Violence Against Women (OVW). (2023, March). What is domestic violence? Department of Justice. Retrieved from: https://www.justice.gov/ovw/domestic-violence

- Sanctuary for Families. (2022, July). The link between disability and domestic violence. Retrieved from: https://sanctuaryforfamilies.org/disability-domestic-violence/

- Screening for Intimate Partner Violence, Elder Abuse, and Abuse of Vulnerable Adults: Recommendation Statement. (2019). American family physician, 99(10), .

- Taylor, V. (2022). When immigration becomes a tool in intimate partner violence. Retrieved from: https://bwjp.org/when-immigration-becomes-a-tool-in-intimate-partner-violence/?gclid=CjwKCAjwq4imBhBQEiwA9Nx1BjBxfxvBc9Mei36iutSPnSVwzwBynoEOQ5BDngmoCCcNu-pF7qY2xxoC2vkQAvD_BwE

- United States Department of Justice. (2000). Full Report of the Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence Against Women. Retrieved from: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/183781.pdf

- Women’s Rights Project. (n.d.). Domestic violence and homelessness. American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved from: https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/dvhomelessness032106.pdf

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate