Constipation Management and Treatment

Contact Hours: 1

Author(s):

Abbie Schmitt MSN-Ed, RN

Course Highlights

- In this course we will discuss the physiological processes involved in normal bowel function

- You’ll also learn how to identify how these processes are disrupted in constipation

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of the common causes of constipation and its treatment.

Introduction

Constipation is more than just an uncomfortable topic—it’s a challenge that nurses encounter very frequently across diverse patient populations. From post-operative recovery to chronic conditions, managing constipation effectively can significantly impact a patient’s comfort, recovery, disease management, and overall quality of life.

There is a deeper need for empathy, education, and evidence-based care. This course invites you to dive into the science of managing constipation with knowledge and compassion.

Understanding Constipation

Constipation is a condition characterized by infrequent, difficult, or incomplete bowel movements, often accompanied by hard or dry stools (3). It is one of the most common problems individuals face and occasionally results in emergent issues.

Constipation can be classified as a primary disorder or secondary to many potential causes.

Primary Constipation

Primary constipation is not caused by an underlying medical condition, medication, or structural abnormality (8). Essentially, the problem arises from bowel functions rather than from a disease or physical obstruction. Primary constipation is also called idiopathic constipation (3). Causes of primary constipation include dietary, lifestyle, neuromuscular, and psychological factors.

Although an underlying medical condition does not cause primary constipation, it can significantly affect quality of life. Understanding its types and causes is essential for effective management and improved patient outcomes.

Primary constipation can be considered as (1) functional constipation, in which stool appropriately passes through the colon at a normal rate, or (2) slow transit constipation, where stool passes through the colon at a prolonged, slow rate (3).

Anorectal dysfunction is the inefficient coordination of the pelvic musculature in the evacuation mechanism and is typically an acquired behavioral disorder.

Secondary Constipation

Secondary constipation can be caused by chronic diseases, certain medications, or anatomic abnormalities (3). The etiology will be further evaluated in an upcoming section.

Epidemiology

Constipation is a common symptom, impacting up to 10% to 20% of the general population (6). The exact prevalence is underestimated because studies show that most patients do not seek out medical care for constipation. The prevalence of chronic constipation is increasing due to changes in diet composition, accelerated pace of life, and the influence of complex social and psychological factors.

Epidemiological surveys have shown that the incidence of chronic constipation is between 14 and 30% worldwide, affecting individuals of all ages, races, socioeconomic status, and nationalities (10). However, certain populations are impacted at higher rates.

The rates of constipation increase with age, affecting roughly one-third of individuals over 60 (6). Individuals residing in nursing homes are more commonly reported. Another risk factor is gender, as constipation affects women more than men (7). Recent studies have also noted a two-fold higher rate of constipation among African Americans and those with lower socioeconomic status (income <$20,000 per year) (6).

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the non-medical factors that impact health outcomes, and they encompass the environments in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, as well as the systems and structures that shape these conditions (9). SDOH significantly impacts health, quality of life, and health disparities across different populations, and research shows a correlation with constipation. These include lifestyle, demographics, education, healthcare access, and medication adherence (7).

Ask yourself...

- How would you describe the difference between primary and secondary constipation?

- What populations are more impacted by constipation?

- How can lifestyle, demographics, and education impact overall health?

- Can you discuss the reasons that chronic constipation rates may be increasing?

Pathophysiology

The underlying pathophysiology of constipation varies among individuals. There are basic mechanical pathophysiological functions, such as changes in feces once they stay in the rectum for too long and changes in mucous membrane sensitivity and peristalsis if the urge is ignored.

The pathophysiology of constipation can be categorized based on the underlying causes and mechanisms. These categories help identify the factors contributing to constipation and guide appropriate interventions. The primary mechanisms are colonic sensorimotor dysfunction and microbiome alteration (10). Factors associated with these mechanisms include gastrointestinal motility and fluid transport, anorectal movement and sensory functions, and dietary and behavioral factors.

Constipation occurs when the fecal mass stays in the rectal cavity for an extended period that is either atypical for the patient or less than three times within a week (5). As the fecal material lingers in the rectum, additional water is absorbed, and the feces becomes smaller, firmer, drier, and more difficult (or painful) to pass.

The common saying, “Use it or lose it!”, can describe another pathophysiological constipation process: “Use it or lose it!” In this case, when the urge to defecate is ignored, it becomes less recognized. Laxation is the term used for the urge to have a bowel movement (8), so when the urge is ignored, the muscular and rectal mucous membranes become less sensitive to the presence of fecal matter in the rectum (8).

It is important to review gastrointestinal mobility.

Gastrointestinal Motility

Gastrointestinal (GI) motility is the coordinated contractions of the muscles in the gastrointestinal tract that move food and waste products. This process is essential for digestion, the absorption of nutrients, and the exit of stool.

Components of GI Motility:

- Peristalsis is the wave-like contractions that move food along the digestive tract.

- Segmental contractions are rhythmic contractions that mix food with digestive enzymes and promote absorption.

- Tonic contractions are sustained muscle contractions that maintain tone in certain areas, such as the sphincters.

Anorectal dyssynergy is a dysfunction of the coordination between the rectal and pelvic floor muscles during defecation and is a common cause of chronic constipation. Normally, defecation involves the relaxation of the anal sphincter and pelvic floor muscles, combined with an increase in intra-abdominal pressure. In anorectal dyssynergy, this process is disrupted, leading to difficulties in stool evacuation despite the presence of normal colonic transit.

Diagnosis is typically made using tests such as anorectal manometry or balloon expulsion tests, and treatment may involve biofeedback therapy, pelvic floor exercises, or other interventions aimed at strengthening the muscles for coordination during defecation.

One prospective study of patients with chronic constipation showed that there was an inability to coordinate the abdominal, rectal, and pelvic floor muscles during defecation. This inability includes impaired rectal contraction, paradoxical anal contraction, or inadequate anal relaxation. (6)

Ask yourself...

- What happens to fecal material when stored in the rectum for an extended period?

- Can you describe anorectal dyssynergy?

- What are possible reasons the urge to defecate may be ignored?

- Can you explain why gastrointestinal mobility (peristalsis, contraction, etc.) is essential to digestion, absorption of nutrients, and the exit of stool?

Etiology and Risk Factors

Constipation can result from a variety of interconnected factors that influence bowel function. Nurses should recognize the different etiologies of primary and secondary constipation.

Underlying Causes of Primary Constipation

Remember – primary constipation results from irregular bowel functions, not an underlying medical condition or medication. This type of constipation is commonly the cause of daily lifestyle factors. These lifestyle factors can be grouped as dietary and functional.

- Dietary factors

- Low fiber intake

- Lack of nutrient-dense foods

- Inadequate fluid intake

- Irregular eating patterns

- Functional factors

- Low or minimal physical activity

- Ignoring the urge to defecate

- Pain or discomfort with defecation

- Weak abdominal muscles

- Environmental changes or time constraints

- Lack of privacy leads to avoidance of a bowel movement for extended periods.

Underlying Causes of Secondary Constipation

- Endocrine/metabolic disorders

- Hyperparathyroidism

- Diabetes mellitus

- Uremia

- Hypercalcemia

- Hypothyroidism

- Myopathic conditions

- Amyloidosis

- Myotonic dystrophy

- Scleroderma

- Neurologic diseases

- Autonomic neuropathy

- Cerebrovascular disease

- Hirschsprung’s disease

- Multiple sclerosis

- Parkinson’s disease

- Spinal cord injury/tumor

- Psychological conditions

- Anxiety/depression

- Somatization

- Structural abnormalities

- Anal fissure/stricture or hemorrhoid

- Colonic stricture

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Obstructive colonic mass

- Rectal prolapse or rectocele

- Others

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Pregnancy

- Medications

- Antacids

- Anticholinergics

- Antidepressants

- Antihistamines

- Calcium channel blockers

- Clonidine

- Diuretics

- Iron

- Narcotics

- NSAIDS

- Opioids

- Psychotropics

- Sympathomimetics (3)

Ask yourself...

- How does the etiology of primary and secondary constipation differ?

- Are you familiar with medications that can cause constipation?

- How can medication reconciliation play an important part in preventing compiling side effects?

- Can you discuss structural abnormalities and conditions that may lead to constipation?

Signs and Symptoms

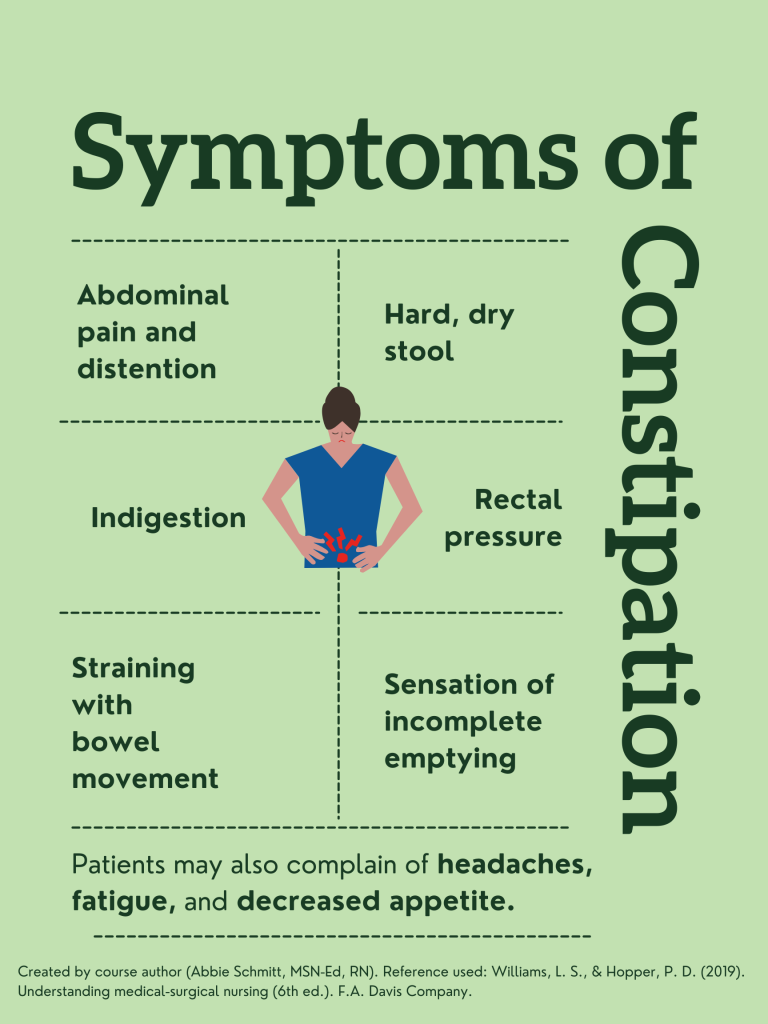

The most common symptoms of constipation are abdominal distention and discomfort, indigestion, “rumbling” of the intestinal system, straining during bowel movements, sensation of incomplete emptying, and rectal pressure (8). The description of stool is a key factor in clinical symptomology. The stool will likely be dry, hard, fragmented, and difficult or painful to pass. There may be findings of fresh bleeding (bright red) around the rectum, or protrusions.

Patients may also report fatigue, decreased appetite, and headache (5). There may also be mood changes related to constipation, such as irritability or depression (4).

Ask yourself...

- What are the most common symptoms of constipation?

- Can you think of words patients may use to describe abdominal discomfort or indigestion?

- Are you familiar with ways of assessing rectal bleeding?

- What are mood changes that may correlate with constipation?

Assessment

A thorough history and physical examination are essential. Patients may feel uncomfortable or self-conscious when discussing bowel habits. Establishing a trusting and comfortable rapport before asking these questions is important. Providing privacy is meaningful.

Data Collection

- Onset, nature, duration of constipation.

- Past bowel movement patterns

- Current bowel patterns

- Occupation

- Lifestyle habits (nutrition, exercise, stress, coping, support)

- History of laxative or enema use

- Current medication regimen (8)

Focused Assessment

- Inspect the abdomen for distention and symmetry

- Palpate the abdomen to assess for tenderness or distention.

- Rectal examination may identify anal fissures and hemorrhoids, which can contribute to painful bowel movements.

- Assessment of the anal sphincter tone can provide clues of neurological disorders which may impair sphincter function.

- A digital rectal exam may also reveal a rectal mass or retained stool. (8)

Labs

- CBC

- BMP: calcium and creatinine levels

- TSH

Endoscopy

- Colonoscopy procedures should follow current guidelines.

- Patients with constipation and “red flag” symptoms of rectal bleeding, heme-positive stool, iron deficiency anemia, weight loss of >10 lbs., obstructive symptoms, or family history of colorectal cancer (3).

Radiography imaging is not especially helpful in underlying etiology, but it may detect stool retention. Barium radiographs may help detect Hirschsprung’s disease. Secondary tests such as anorectal manometry and colonic transit studies can be used to evaluate patients whose constipation is refractory (3).

Diagnosis Criteria

Chronic constipation is usually outlined by clinical symptoms known as the Rome criteria. The Rome IV diagnostic criteria define functional constipation as two or more findings occurring in at least 25% of defecations.

- Straining during the bowel movement

- Lumpy or hard stool

- A sensation of incomplete evacuation

- A sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage

- The use of manual maneuvers to facilitate defecation.

- Loose stools are rare without the use of laxatives

- Having fewer than three spontaneous defecations per week.

The criteria also require these findings to be present for over 3 months, with an initial symptom onset longer than 6 months. (2,3)

Ask yourself...

- Can you describe the Roma IV diagnostic criteria for constipation?

- Why are bowel patterns and history important to the assessment of constipation?

Treatment

Nonpharmacologic Treatments

- Bowel training – Encourage patients to attempt a bowel movement in the morning, shortly after awakening, when the bowels are more active, and 30 min after meals to encourage gastrocolic reflex.

- Increase dietary fiber intake

- The recommended intake is 20–35 g daily and an increase of 5 g daily until the recommended daily intake is reached. Increase fiber-rich foods: bran, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and prune juice.

- Psyllium and methylcellulose are the most effective forms of fiber replacement.

- Increase fluid intake – decreased intake may result in fecal impaction

- Regular exercise

- Biofeedback/ pelvic floor retraining – useful for anorectal dysfunction. (3)

Pharmacologic Treatment

A clinical practice guideline jointly developed by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) provides evidence-based recommendations for the pharmacological treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC) in adults (1).

The guidelines provide strong recommendations for using polyethylene glycol, sodium picosulfate, linaclotide, plecanatide, and prucalopride based on evidence for effectiveness. Conditional recommendations were given for using fiber, lactulose, senna, magnesium oxide, and lubiprostone, emphasizing the need for individualized treatment approaches. The guidelines highlight an individualized approach considering patient preferences, lifestyle, costs, and medication availability (2).

Types of pharmacological treatments:

- Bulk laxatives – Citrucel and Metamucil absorb water from the intestinal lumen to increase stool mass and soften stool consistency.

- Recommended for patients with functional normal transit constipation.

- Side effects include bloating and increased gas production.

- Emollient laxatives—stool softeners: docusate lowers surface tension, thereby allowing water to more easily enter the bowel.

- Not as effective as bulk laxatives but useful in patients with painful defecation conditions such as hemorrhoids or anal fissures.

- Osmotic laxatives

- Milk of magnesia, magnesium citrate, MiraLAX, and lactulose hyperosmolar agents use osmotic activity to secrete water into the intestinal lumen.

Precautions:

- Monitor for electrolyte imbalances such as hypokalemia and hypermagnesemia.

- Use with caution in congestive heart failure and chronic renal insufficiency patients.

- Stimulant laxatives: Dulcolax, senna, tegaserod, castor oil, and bisacodyl increase intestinal motility and secretion of water into the bowel.

- Common side effects include abdominal discomfort and cramping as a result of increased peristalsis.

- Contraindicated for patients with suspected bowel obstruction. (3)

Complications

The most common complications associated with constipation are discomfort and irritation that can lead to:

- Hemorrhoids

- Rectal bleeding

- Anal fissures

Sometimes, the difficulty passing a bowel movement can cause more serious complications, such as:

- Rectal prolapse (the large intestine detaches inside the body and pushes out of the rectum)

- Fecal impaction (hard, dry stool is stuck in the body and unable to be expelled naturally)

Constipation significantly impacts quality of life (QOL), affecting physical and emotional well-being. Patients with constipation may experience more negative QOL. Studies reported that chronic constipation also causes greater school and work absenteeism and loss of productivity (4).

Nursing Implications and Patient Education

Patient education is an important component of effective constipation management.

Assessment of Knowledge and Baseline Habits

- Assess the patient’s current understanding of constipation and its causes.

- Evaluate dietary habits, fluid intake, physical activity, and medication use that may contribute to constipation.

Provide education on the following:

- Causes and Risk Factors

- Risk factors include low fiber intake, inadequate hydration, lack of physical activity, and certain medications (e.g., opioids, and iron supplements).

- Discuss specific risk factors such as age, medical conditions (e.g., diabetes, hypothyroidism), or recent surgeries.

- Lifestyle Modifications

- Dietary Changes

- Hydration

- Physical Activity

- Healthy Bowel Habits

- Encourage patients to respond promptly to the urge to defecate to avoid hardening of stools and reduced sensitivity.

- Recommend a regular bowel routine, such as attempting bowel movements after meals to take advantage of the gastrocolic reflex.

- Discuss Medication Use

- Advise patients on the appropriate use of laxatives, stool softeners, and other medications for short-term relief.

- Discourage routine use of laxatives and enemas to avoid trauma to the intestinal mucosa, dehydration, and eventual failure of defecation stimulus. (Bulk-adding laxatives are not irritating and are usually permitted.)

- Address Psychological Factors

- Tailor Education to Special Populations

- Encourage Self-Monitoring Log

- Teach patients to track their bowel habits, dietary intake, and hydration levels to identify patterns and triggers.

- Provide Written Materials and Resources

- Offer brochures, handouts, or trusted websites for additional information.

In the inpatient settings, nursing interventions should include:

- Record intake and output accurately to ensure correct fluid replacement therapy.

- Note the color and consistency of stool and frequency of bowel movements to form the basis of an effective treatment plan.

- Promote ample fluid intake, if appropriate, to minimize constipation with increased intestinal fluid content.

- Encourage the patient to increase dietary fiber intake to improve intestinal muscle tone and promote comfortable elimination.

- Encourage the patient to walk and exercise as much as possible to stimulate intestinal activity.

Ask yourself...

- Why is it important to discourage patients from overusing laxatives and enemas?

- How can nurses encourage bowel training routines?

- Can you name the major lifestyle modifications that are important in constipation management?

- Are you familiar with fiber-rich foods?

Conclusion

Constipation is a common but complex condition that can significantly impact a person’s quality of life and overall health. Nurses play a meaningful role in identifying, preventing, and managing constipation through comprehensive assessment, evidence-based interventions, and patient education.

Understanding the underlying causes and employing tailored strategies can empower patients to take control of their bowel health. This course has taught learners the knowledge and tools to approach constipation with confidence, compassion, and clinical expertise. Remember that even small changes in habits can lead to meaningful improvements in well-being.

References + Disclaimer

- American Gastroenterological Association. (2023). ACG and AGA guideline on chronic constipation management is first to recommend supplements magnesium oxide and senna as evidence-based treatments. Retrieved December 24, 2024, from https://gastro.org/press-releases/acg-and-aga-guideline-on-chronic-constipation-management-is-first-to-recommend-supplements-magnesium-oxide-and-senna-as-evidence-based-treatments/

- Chang L, Chey WD, Imdad A, Almario CV, Bharucha AE, Diem S, Greer KB, Hanson B, Harris LA, Ko C, Murad MH, Patel A, Shah ED, Lembo AJ, Sultan S. American Gastroenterological Association-American College of Gastroenterology Clinical Practice Guideline: Pharmacological Management of Chronic Idiopathic Constipation. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jun;164(7):1086-1106. Doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.03.214. PMID: 37211380; PMCID: PMC10542656.

- Huang, D. (2024). Constipation. In: Desai, B.K., Desai, A., Ganti, L., Elbadri, S. (eds) Primary Care for Emergency Physicians. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-64676-8_17

- Jiang Y, Tang Y, Lin L. Clinical Characteristics of Different Primary Constipation Subtypes in a Chinese Population. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020 Aug;54(7):626-632. Doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001269. PMID: 31592795; PMCID: PMC7368843.

- Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, editor, Cromar, K. C., & Moebius, C. (2023). Medical-surgical nursing made incredibly easy! (5th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

- Rao, S. S. C., Parkman, H. P., & McCallum, R. W. (Eds.). (2024). Handbook of gastrointestinal motility and functional disorders (First edition.). CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003524519

- Werth BL, Christopher SA. Potential risk factors for constipation in the community. World J Gastroenterol. 2021 Jun 7;27(21):2795-2817. Doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i21.2795. PMID: 34135555; PMCID: PMC8173388.

- Williams, L. S., & Hopper, P. D. (2019). Understanding medical-surgical nursing (6th ed.). F.A. Davis Company.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2024). Social determinants of health. Retrieved, from https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1.

- Zhao Q, Chen YY, Xu DQ, Yue SJ, Fu RJ, Yang J, Xing LM, Tang YP. Action Mode of Gut Motility, Fluid and Electrolyte Transport in Chronic Constipation. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Jul 27;12:630249. Doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.630249. PMID: 34385914; PMCID: PMC8353128.

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback!

Create your own user feedback survey