Course

Diabetic Foot Ulcers

Course Highlights

- In this course we will describe the pathophysiological mechanisms that lead to the development of diabetic foot ulcers

- You will learn how to identify key risk factors and their complication in individuals with diabetes

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 2

Course By:

Abbie Schmitt

MSN-Ed, RN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

This course is designed to empower nurses with the knowledge and skills needed to effectively manage diabetic foot ulcers, which are common and serious complications of diabetes. Learners will gain a thorough understanding of the pathophysiology of DFUs, risk factors, and evidence-based prevention and treatment strategies. The course integrates practical applications, including wound assessment, advanced dressing techniques, and patient education, to improve healing outcomes and reduce complications such as infections and amputations.

Introduction

Every step matters—especially for patients with diabetes. Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) are more than just wounds; they are a leading cause of hospitalizations, infections, and amputations, which profoundly impact a patient’s quality of life. These ulcers are preventable, manageable, and treatable with intervention.

This course will equip learners with knowledge of the complexities of DFUs—from understanding the intricate balance between neuropathy, ischemia, and infection to mastering evidence-based prevention strategies and advanced wound care techniques. Learners will explore the pathophysiology, epidemiology, etiology, management, nursing considerations, and emerging research on advanced treatment methods for this devastating complication.

Definitions

Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) are full-thickness wounds involving the dermis in the weight-bearing or exposed foot area. They develop in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes (19, 21).

Skin ulcers are defined as a break in the continuity of the lining epithelium, which is a stratified squamous epithelium that reveals the raw surface of the underlying tissue. The loss of the protective keratin and keratinocytes and a defect in the anchoring basement membrane causes this breach in the skin. (8)

Epidemiology

Did you know that roughly 15% of the U.S. population 18 years and older has diabetes, based on statistics from the CDC? Approximately 1.2 million individuals in the U.S. were newly diagnosed with diabetes in 2021 (3).

The CDC provided the information on the demographics below (3):

| Demographic | Total Diabetes Percentage

(within specific characteristics) |

| Age | |

| 18-44 | 4.8% |

| 45-64 | 18.9% |

| ≥65 | 29.2% |

| Race/ Ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 13.6% |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 17.4% |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 16.7% |

| Hispanic | 15.5% |

Globally, it is estimated that 239.7 million people are unaware of their diabetes (18).

Roughly 15% of individuals diagnosed with diabetes will eventually develop DFU, and 14%-24% of them will require amputation of the affected foot due to ulcer-related complications (19).

Mortality following diabetes-related amputation is very high; the estimated five-year mortality is up to 79% following minor amputation and up to 91.7% following major amputation, with notably higher mortality in older adults and those with CKD and PAD (13).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you discuss which age groups have the highest prevalence of diabetes?

- What is the likelihood that an individual with diabetes will eventually develop a diabetic foot ulcer?

- Can you describe statistics related to amputation and mortality for individuals with DFUs?

- How are describe DFUs to patients and caregivers?

Pathophysiology

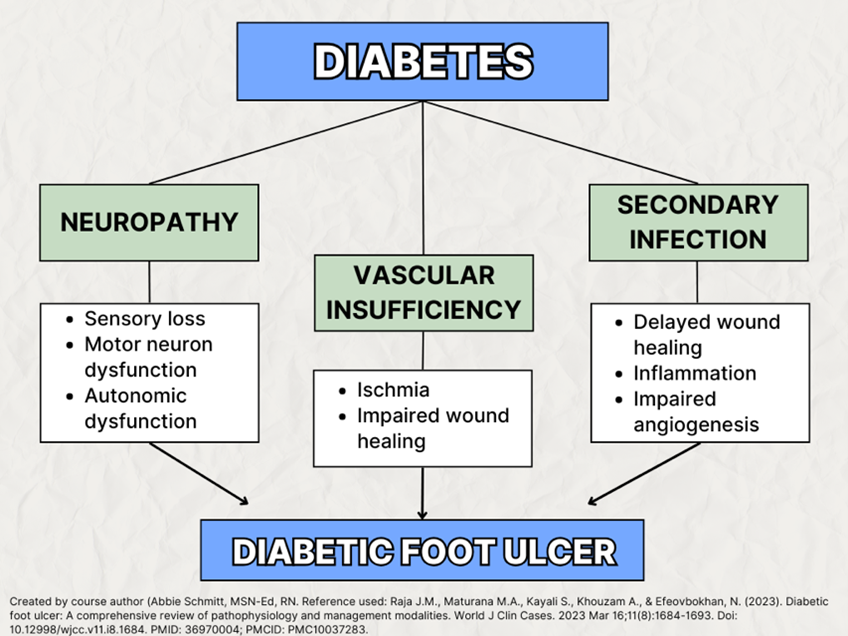

The pathologic mechanisms underlying DFU can be described using three pathways stemming from uncontrolled diabetes: neuropathy, vascular insufficiency, and secondary infection due to foot trauma.

Neuropathy

Neuropathy is damage or dysfunction of nerves, resulting in symptoms such as numbness, tingling, muscle weakness, and pain in the affected area. Diabetic neuropathies encompass conditions that impact the peripheral nervous system, each having distinct functions, including nerves, fibers, and nerve roots, expressing sensory, motor, and autonomic abnormalities.

The underlying pathophysiology of diabetic foot neuropathy leading to ulcers is a complex process driven by chronic hyperglycemia. Neuropathy involves sensory impairment due to hyperglycemia-induced impaired regulation of aldose reductase and sorbitol dehydrogenase, increasing the production of fructose and sorbitol (19). When fructose and sorbitol accumulate, they induce osmotic stress and reduce nerve conduction.

In addition to sensory neurons, motor neurons are also impacted by neuropathy. Motor neuron dysfunction can lead to muscle degrading of the foot, which causes increased pressure in various areas of the plantar foot and increases the likelihood of ulceration (19). Neuronal autonomic dysfunction is another effect, which leads to poor sweat production, dryness, skin cracking, and ulceration.

Diabetic neuropathy is like a frayed electrical wire, where the signals meant to power sensation, movement, and function flicker unpredictably—sometimes creating pain sensation, other times just a lack of making any sensation and numbness.

The main types of diabetic neuropathy:

Peripheral Neuropathy (PN): The most common form of diabetic neuropathy. Peripheral neuropathy is nerve damage that impacts the extremities, typically the feet and legs (8).

Autonomic Neuropathy: This form impacts the autonomic nervous system, which controls functions like digestion, heart rate, and bladder control. Symptoms may include bladder or bowel problems, nausea, loss of appetite, and sexual dysfunction.

Proximal Neuropathy: This form impacts proximal nerves, including the thighs, hips, buttocks, or upper legs, leading to pain and muscle weakness in these areas.

Focal Neuropathy: This form involves dysfunction of a specific nerve, commonly in the head, torso, or leg, causing sudden weakness or pain.

Diabetic polyneuropathy refers to damage to multiple peripheral nerves caused by prolonged exposure to elevated blood glucose levels in individuals with diabetes. It primarily affects the sensory nerves, though motor and autonomic nerves can also be involved, leading to widespread nerve dysfunction. Among the sensorimotor neuropathies, diabetic polyneuropathy is the most common (>80%) (12).

Cardiovascular Autonomic Neuropathy (CAN) may be completely asymptomatic and detected only by decreased heart rate variability with deep breathing. Advanced disease may be manifested by resting tachycardia and orthostatic hypotension (1).

Causes (other than diabetes) of neuropathy include toxins (e.g., alcohol), neurotoxic medications (e.g., chemotherapy), vitamin B12 deficiency, hypothyroidism, renal disease, malignancies (e.g., multiple myeloma, bronchogenic carcinoma), infections (e.g., HIV), chronic inflammatory demyelinating neuropathy, inherited neuropathies, and vasculitis (1).

Managing blood sugar levels is crucial in preventing or delaying the onset of diabetic neuropathy. Regular monitoring and maintaining a healthy lifestyle can significantly reduce the risk of nerve damage associated with diabetes.

Vascular Insufficiency

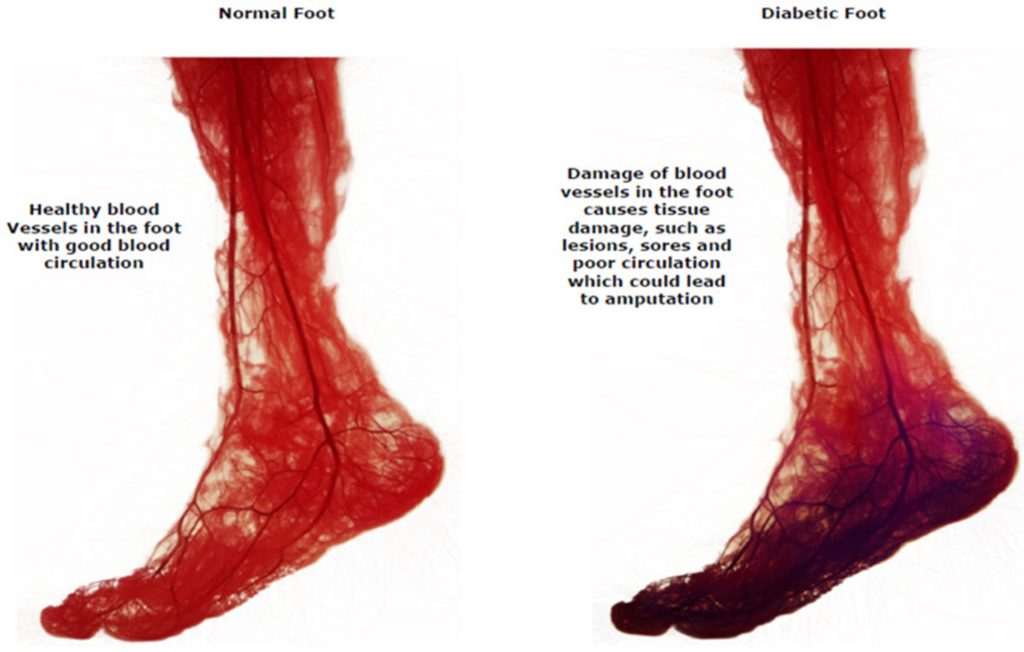

Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD) is a circulatory condition characterized by the narrowing or blockage of arteries that supply blood to the extremities. Diabetes is a significant risk factor for the development of PAD. Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD) in diabetes is primarily caused by atherosclerosis, the narrowing and hardening of arteries due to plaque buildup. However, diabetes accelerates and worsens the progression of PAD through several unique mechanisms, resulting in more severe disease.

High blood glucose levels damage the endothelium (inner lining of blood vessels), which damages its ability to regulate blood flow and vascular tone. Oxidative stress caused by hyperglycemia produces reactive oxygen species (ROS), which reduce the availability of nitric oxide (NO), a vasodilator. This leads to vasoconstriction and reduced blood flow. Additionally, endothelial damage triggers chronic inflammation, which increases the development of atherosclerosis. (7)

In people with diabetes, it is common to see (1) long-segment tibial artery occlusions and (2) infragenicular arterial occlusive disease.

Poor peripheral circulation in diabetes is associated with a greater likelihood of delayed or nonhealing of wounds on the foot and gangrene. The prognosis of a person with diabetes, PAD, and foot ulceration requiring amputation is worse than for many common cancers; it is estimated that up to 50% of these individuals will not survive five years (7).

Early and ongoing assessment of extremity perfusion is vital for those with diabetes.

(9) CC BY 4.0

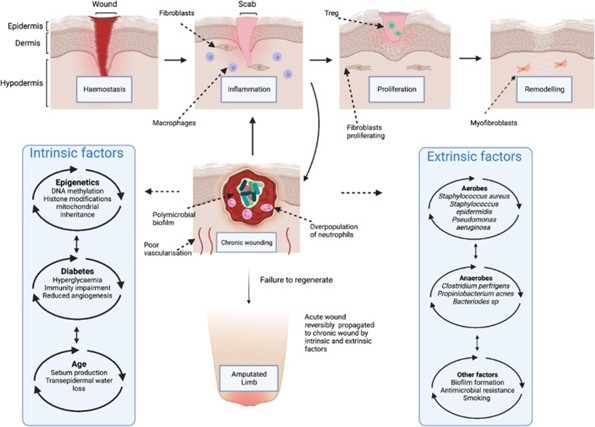

Impaired Wound Healing

Hyperglycemia causes complex molecular dysfunctions in wound healing. Ordinarily, wounds undergo several healing stages involving hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling; however, nonhealing DFUs stop the progression of these stages.

In the early phases of wound healing, neutrophils typically release granular molecules to kill foreign pathogens, known as neutrophil extracellular traps (19). However, in a diabetic microenvironment, a proinflammatory cascade and overproduction of cytokines and superoxide occur during this stage, often delaying wound healing.

Hyperglycemia induces the formation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), which are non-enzymatic proteins, amino acids, and DNA components that produce dicarbonyls and glucose, which are known to induce structural and functional changes in key proteins (19). This process prolongs inflammation.

Along with inflammation, there are significant changes within the extracellular matrix (ECM) for nonhealing DFUs. In routine wound healing, the production and degradation of ECM proteins such as collagen and fibrin are strictly regulated; however, prolonged hyperglycemia disrupts this process and impairs the function of these wound-healing proteins.

Lastly, impaired angiogenesis occurs in diabetic wound healing. Angiogenesis is the biological process of new blood vessel formation from pre-existing vessels and ordinarily occurs during the proliferative phase of wound healing. These vessels are responsible for both the formation of granulation tissue and the delivery of nutrition and oxygen to the wound (19).

Phases of Wound Healing

When caring for patients with, or at risk for, DFUs, it is important to recognize the normal phases of wound healing.

- Inflammation Phase: This phase incorporates the vascularized living tissue response to injury. The inflammation attempts to remove and debride the injured areas from foreign bodies and to remove dead cells. This process also facilitates edema formation.

- Proliferative Phase

- In acute inflammation, angiogenesis occurs, causing dilatation and hyperemia at the arterial end and increased permeability at the venular end of the vascular bed. This is a critical process that allows the formation of new blood vessels to provide building blocks, which are oxygen and nutrients, for the repair process.

- Collagen formation occurs as mature granulation tissue and blood vessels produce proteins and extracellular matrix, which is then surrounded by a plethora of inflammatory cells.

- Epithelization: Epithelial cells from the epidermis below start to form a monolayer from the edges to cover the opening (wound), and as they reach the mid-line and seal the gap, they activate a vertical maturation step.

- Maturation Phase: This is a continuous process. As it matures, the tissue’s color fades from red to light pink to white.

(8)

Secondary Infections

There is a definite impairment of immunological function in those with diabetes. Polymorphonuclear cells are more prevalent in the presence of hyperglycemia, and these cells reduce microbiocidal activity and are a significant contributing factor in the establishment of wound infections (17).

Vitamin D Deficiency

A systematic review and meta-analysis examined the association of vitamin D levels with foot ulcers; severe vitamin D deficiency was reported in 48.98% of the participants with diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) and in 22.78% of the participants with diabetes without DFU (5). This study’s authors and various other studies have concluded that severe vitamin D deficiency, classified as 25-(OH)D less than 10 ng/mL, is significantly associated with an increased risk of DFU (5, 15).

Vitamin D has many significant roles in circulation and wound healing. It helps regulate immune cell activity, such as macrophages and neutrophils, which are critical in clearing debris and pathogens during the inflammatory phase of wound healing. Without adequate vitamin D, immune function is compromised. Vitamin D also helps modulate the inflammatory phase of wound healing and collagen production, and deficiency can lead to prolonged or excessive inflammation and delay tissue repair (15).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you describe the underlying pathophysiology of prolonged hyperglycemia on the development of neuropathy?

- How does peripheral neuropathy differ from autonomic neuropathy?

- Can you discuss the phases of routine wound healing?

- How does poor circulation correlate with skin breakdown, healing, and infection?

Risk Assessment and Prevention

Risk factors for diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) include:

- Poor glycemic control

- Peripheral neuropathy

- A history of foot ulcers or amputations, foot deformities

- Improper footwear

- Obesity

- Peripheral arterial disease (PAD)

- Smoking

- Long duration of diabetes

- Poor vision

- Impaired mobility

- Psychological or social factors (lack of healthcare access and education)

- Chronic kidney disease (CKD)

As we discussed, poor glycemic control results in chronic hyperglycemia, which damages blood vessels and nerves, impairing circulation and sensation, and ultimately leads to an increased risk of ulcers and delayed healing.

Peripheral neuropathy causes loss of sensation, and painful stimuli can often be a protective mechanism of the nervous system – alerting to danger. Sensory neuropathy causes reduced or absent sensations like pain, pressure, and temperature. This lack of protective sensation in the feet can increase the risk of trauma and ulcers. Patients may not feel injuries such as cuts, blisters, or burns, which go unnoticed and untreated, initiating skin breakdown and ulcer formation.

For example, an individual with diabetic neuropathy walks on their extremely hot asphalt driveway barefoot to get their mail, not realizing the temperature caused a second-degree burn. Poor vision or reduced mobility makes inspecting and caring for the feet even more difficult.

Motor neuropathy causes muscle weakness, foot deformities, and abnormal pressure distribution, while autonomic neuropathy reduces sweating, causing dry and cracked skin that increases the risk of ulceration. Obesity causes further pressure and risk for skin breakdown. Foot deformities, such as hammer toes, claw toes, or bunions, create pressure points and friction in footwear, leading to breakdown and ulcers. When patients wear Ill-fitting shoes, they can rub and cause blisters, calluses, or ulcers, especially in individuals with neuropathy or foot deformities.

PAD reduces blood flow to the extremities, limiting oxygen and nutrient delivery, impairing wound healing, and increasing the likelihood of ulcers. Smoking causes vasoconstriction and accelerates atherosclerosis, which reduces blood flow to the feet.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is also a risk factor for DFUs due to impaired healing and systemic vascular disease associated with CKD.

When individuals live with diabetes for longer durations of time, the cumulative damage to nerves and blood vessels increases the risk of ulcers. Lack of healthcare access, insufficient education about foot care, and poor adherence to diabetes management plans also increase the likelihood of developing foot ulcers.

Social Determinants of Health (SDOH)

The study of the social determinants of health (SDOH) identifies social factors contributing to health outcomes, which is especially important in managing diabetes. Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the conditions in the environments where individuals are born, reside, work, interact with others, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks (Healthy People 2030, 2020).

For individuals with diabetes and diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs), these determinants play a crucial role in the development, management, and prevention of complications.

(10)

The following SDOHs are impactful in diabetes and DFUs:

- Income and Poverty

- Low-income individuals are at a higher risk for uncontrolled diabetes and DFUs due to limited access to healthy food, medications, and healthcare services.

- Financial instability can delay treatment for DFUs, increasing the risk of infection, poor healing, and amputation.

- Access to Healthcare

- Limited access to specialists, such as podiatrists, delays treatment

- Rural or underserved areas may lack wound care clinics and diabetes education programs.

- Individuals without adequate health insurance are less likely to seek preventive care, regular foot exams, or timely treatment for DFUs.

- Early screenings for diabetes or education about foot care increase the risk of complications, so those who lack these are at higher risk.

- Neighborhood and Physical Environment

- Homelessness or inadequate housing can lead to poor foot hygiene, lack of footwear, and delayed wound care.

- Areas with limited access to affordable, healthy food contribute to poor nutrition, obesity, and poorly managed diabetes.

- Lack of accessible transportation may prevent individuals from attending medical appointments.

- Language and Cultural Barriers

- Language barriers can prevent patients from understanding care instructions, medication use, and the importance of preventive measures like foot care.

- Various cultural norms, such as using traditional remedies over medical care, may delay the treatment of DFUs.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you describe the impact of poverty and economic burdens on diabetes management?

- How can cultural practices impact the prevention of diabetes complications?

- Can you list risk factors associated with developing DFUs?

- How can comorbidities such as heart or kidney disease increase a diabetic patient’s risk for foot ulcers?

Standards of Care for Diabetes

Awareness and adherence to evidence-based practice guidelines for diabetes care and prevention of complications are paramount in preventing and managing DFUs.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) “Standards of Care in Diabetes” provides the current clinical practice recommendations on general treatment goals and guidelines (1).

ADA’s Guidelines on Neuropathy (1)

- All people with diabetes should be assessed for diabetic peripheral neuropathy starting at the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and 5 years after the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and at least annually afterward.

- Assessment for distal symmetric polyneuropathy should include a thorough history and evaluation of temperature or pinprick sensation (small-fiber function) and vibration sensation using a 128-Hz tuning fork (for large-fiber function).

- Symptoms and signs of autonomic neuropathy should be assessed in people with diabetes starting at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and 5 years after the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes, and at least annually thereafter, and with evidence of other microvascular complications, particularly kidney disease and diabetic peripheral neuropathy.

Peripheral neuropathy should be screened using medical history and simple clinical tests (1). Symptoms vary based on the sensory fibers used. The involvement of tiny fibers induces the most common early symptoms, including pain and dysesthesia (unpleasant sensations of burning and tingling). Large fibers may cause numbness and loss of protective sensation (LOPS). LOPS indicates the presence of distal sensory polyneuropathy and is a risk factor for diabetic foot ulceration (1).

The following clinical tests are essential for assessing function and sensation:

- Small-fiber function: pinprick and temperature sensation.

- Large-fiber function: lower-extremity reflexes, vibration perception, and 10-g monofilament.

- Protective sensation: 10-g monofilament.

(1)

These tests screen for the presence of nerve dysfunction and can predict future risk of complications. In some instances, electrophysiological testing or referral to a neurologist may also be appropriate (1).

The symptoms and signs of autonomic neuropathy should be elicited carefully during the history and physical examination. Clinical manifestations of diabetic autonomic neuropathy include resting tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, gastroparesis, constipation, diarrhea, fecal incontinence, erectile dysfunction, neurogenic bladder, and changes in sweat production (1). Assessment questions for symptoms of autonomic neuropathy include asking about symptoms of orthostatic intolerance (dizziness, lightheadedness, or weakness with standing), syncope, poor exercise tolerance, constipation, diarrhea, urinary retention or incontinence, or changes in sweat function.

In recent years, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) peripheral neuroimaging has increasingly been used to diagnose and evaluate peripheral neuropathy (22).

Foot Care Recommendations (1)

- Perform a comprehensive foot evaluation at least annually

- The examination should include inspection of the skin, assessment of foot deformities, neurological assessment (10-g monofilament testing with at least one other assessment: pinprick, temperature, or vibration), vascular assessment, and assessment of pulses in the legs and feet.

- Those with sensory loss or prior ulceration or amputation should have their feet inspected at every visit.

- Obtain a previous history of ulceration, amputation, Charcot foot, angioplasty or vascular surgery, cigarette smoking, retinopathy, and renal disease and assess current symptoms of neuropathy (pain, burning, numbness) and vascular disease (leg fatigue, claudication). B

- Initial screening for peripheral arterial disease (PAD) should include an assessment of:

- Lower-extremity pulses

- Capillary refill time

- Rubor on dependency

- Pallor on elevation

- Consider specialist referral for individuals who smoke and have a history of prior lower-extremity complications, loss of protective sensation, structural abnormalities, or PAD to foot care specialists for ongoing preventive care (6, 19).

- Provide general preventive foot self-care education, including appropriate ways to examine their feet (palpation or visual inspection with an unbreakable mirror) to monitor for early foot problems daily.

- Educating people with diabetes at high risk for ulceration, including those with loss of protective sensation, foot deformities, ulcers, callous formation, poor peripheral circulation, or a history of amputation, on the use of specialized therapeutic footwear is recommended.

Identifying the at-risk foot begins with a detailed history documenting diabetes management, smoking history, exercise tolerance, history of claudication or rest pain, and prior ulcerations or amputations.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you describe the initial assessment of a diabetic patient with PAD?

- What are the signs and symptoms of autonomic neuropathy?

- Are you familiar with foot examinations and the use of monofilaments?

- What are other reasons, apart from diabetes, that can cause symptoms indicative of peripheral neuropathy?

Wound Assessment and Classification

Assessment of the patient with a DFU includes evaluation of their overall health status and ability to heal, which includes:

- Systemic diseases

- Medications

- Nutrition

- Tissue perfusion and oxygenation

- Skin status

- Wound etiology, severity, and the stage of healing.

The general types of wound assessment are the initial, baseline, and follow-up assessments. The initial baseline assessment provides the foundation for treatment options, the plan of care, patient and caregiver goals, and wound status; the initial data allows comparison with the follow-up assessment to determine if the wound is progressing or deteriorating (2).

The baseline assessment should be done when the wound is first observed or identified. The baseline assessment must be comprehensive. Follow-up assessments provide comparison data, which allow providers to determine wound response to treatment. These should be performed at least weekly, with dressing changes, whenever a change occurs in the wound, or more frequently based on each health care facility policy. (14)

- Skin inspection

- Visually observing all body parts without clothing, socks, or shoes.

- Specific conditions to observe include areas of skin loss, redness or other skin discoloration, edema, rash, increased skin temperature or moisture, and, in the case of a wound, new or increased drainage.

- If a dressing is present and not due to change, the dressing should be observed for intactness and any signs of excess wound drainage, rash, or skin discoloration on the surrounding skin.

- If the dressing is dry and intact, its status should be documented, and removing it is unnecessary.

(14)

Assessment and documentation of wound status is an important nursing responsibility and is best accomplished using a standardized wound assessment instrument to guide the assessment process and provide continuity in communication about the wound. Documentation at each dressing change should include notations about wound location, the appearance of the wound bed, volume and characteristics of exudate, and any evidence of infection, such as erythema (2).

A thorough documentation of wound status should be conducted at least weekly and must include:

- Wound dimensions and depth

- Undermining or pocketing and tunneling

- Description of wound base, wound edges

- Surrounding tissues

- Amount and characteristics of exudate

- Healing characteristics of the wound.

Continuity of assessments is critical; for example, as the amount of necrotic tissue decreases, topical therapy shifts from debridement to maintenance of a moist wound surface and exudate management (2). Photography can be a meaningful tool to enhance this continuity and communication about DFUs.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Why are similarity and continuity of wound assessments critical?

- How can nurses provide patient education during wound assessment?

- Why is it meaningful to thoroughly examine circulation and pulses in extremities?

- What are signs that surrounding tissue is compromised?

Classification of DFUs

Classification systems are essential for optimal clinical care and follow-up. The score is a universal way to describe the wound and identify deterioration or changes.

Two major wound care systems for DFU classification are the Wagner Scale and the University of Texas (UT) Diabetic Wound Classification System.

Wagner System for Classification of DFU

The Wagner System integrates five grades to assess ulcer depth and the presence of osteomyelitis or gangrene.

- Wagner Grade 0: Skin is intact with no open lesion or a pre-ulcerative lesion — may have a deformity or cellulitis

- Wagner Grade 1: Partial- or full-thickness ulcer (superficial ulcer)

- Wagner Grade 2: Deep ulcer extended to ligament, tendon, joint capsule, bone, or deep fascia without abscess or osteomyelitis (OM)

- Wagner Grade 3: Deep abscess, OM, or joint sepsis

- Wagner Grade 4: Partial-foot gangrene

- Wagner Grade 5: Whole-foot gangrene

(8)

University of Texas (UT) Diabetic Wound Classification System

The UT grading system is more descriptive and notes ulcer depth, grade, and stage. It also assesses the presence of wound infection and clinical signs of lower-extremity ischemia. It has been shown to have a more significant association with the prediction of ulcer healing and amputation based on several studies (20).

The grades of the UT system include:

- Grade 0: Pre- or post-ulcerative site (epithelialized wound)

- Grade 1: Superficial wound, not involving the tendon, capsule, or bone

- Grade 2: Wound is penetrating to tendon or capsule

- Grade 3: Wound is penetrating bone or joint

There are four stages within each wound grade:

- Stage A: Clean wounds (no infection, no ischemia)

- Stage B: Nonischemic, infected wounds

- Stage C: Ischemic, noninfected wounds

- Stage D: Ischemic and infected wounds (both present)

(8)

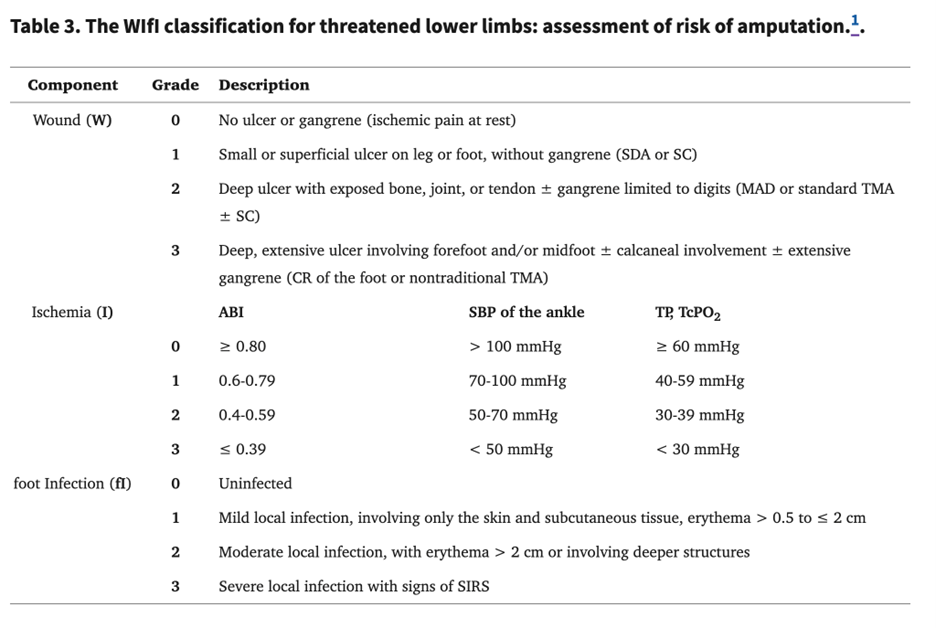

Wifi Classification System

The Society for Vascular Surgery has proposed a new classification system for the classification of DFUs and the prediction of wound healing and amputation. This system is based on the three main factors that have an impact on limb amputation risk: Wound (W), Ischemia (I), and foot Infection (“fI”).

The purpose is to provide accurate and early risk stratification, clinical management, alternative therapies, and limb revascularization needs (4).

(4)

Assessment and risk stratification require consideration of patient comorbidities and systemic patterns of diseases and their severity (4).

Photography

Photography has been used to enhance wound assessment and documentation and to provide visual assessment DFUs over time.

Digital photography has helped diagnose foot ulcers and pre-ulcers in persons with diabetes mellitus (DM) as part of telehealth home monitoring (2). Maximizing their accuracy is important to ensure that wound photographs are clear and valuable. Before taking pictures, it is essential to check each facility’s protocol, as some do not allow it.

Photography guidelines (2):

- Obtain patient authorization according to facility policy before photography. Place the patient in the same position and take all photographs from the same angle.

- Take a close-up photograph of the wound and then a second photograph showing the wound and the body part.

- Place a ruler with centimeters and a color guide in the photograph.

- In the photograph, include a label with the date, anatomic location, and patient identification (ID) number (use a nonidentifiable ID that meets HIPAA regulations).

- Use a digital camera with a density of at least 1.5 megapixels, but 3 megapixels or greater is better for picture clarity.

- Follow strict infection control policies.

- For example, prepare the wound, remove gloves, wash hands, handle the camera, and take the photograph without touching anything around the wound.

- Download the photographs to the patient’s record and delete the picture from the camera memory card.

The stages and findings in DFU cases are very expansive. No two wounds are exactly alike, just like no two patients. We will examine several images of DFUs in common locations at various stages.

Image: Neuropathic DFU on heel

(23) CC BY 3.0

Image: Arterial ulcer in a peripheral vascular disease (PVD) patient.

(24) CC BY 3.0

(25) CC BY 4.0

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Why is patient consent and education necessary in obtaining photos of a wound?

- Are you familiar with staging and classification tools for wounds within the facility that you work in?

- Why is it vital to maintain consistency in the classification and description of DFUs?

- According to the Wagner System, how would the following wound be classified: A deep ulcer that has gone into the underlying tendon and deep fascia but has no signs of infection or abscess?

Evidence-Based Treatment Approaches for Diabetic Foot Ulcers

Initial treatment recommendations should include daily foot inspection, use of moisturizers for dry, scaly skin, and avoidance of self-care of ingrown nails and calluses (1).

The ADA’s position is that the initial treatment and evaluation of ulcerations include the following five basic principles of ulcer treatment:

- Offloading of plantar ulcerations (relieving or minimizing pressure)

- Debridement of necrotic, nonviable tissue

- Revascularization of ischemic wounds when necessary

- Management of infection in the soft tissue or bone

- Use of physiologic, topical dressings

(1)

Negative-pressure wound therapy, placental membranes, bioengineered skin substitutes, several acellular matrices, autologous fibrin and leukocyte platelet patches, and topical oxygen therapy (1) might be considered.

The gold standard for chronic infections is surgical debridement of the wound bed, managing infection using antimicrobial agents, revascularization procedures, and offloading the wound (17).

The ultimate goal for any wound is complete regeneration.

Offloading

Pressure offloading serves as one of the primary treatments for DFU in ulcers with neuropathy. For ischemic DFUs, however, revascularization is a more effective measure.

Standard offloading methods include bed rest, wheelchair use, implementation of crutches or walkers, total contact casting, use of felted foam, and various therapeutic shoes (19). The most effective offloading treatment is total contact casting (TCC), in which full casts are applied by an experienced physiotherapist and are changed weekly until the wound has healed (19). Several studies have found that TCC was more effective in increasing ulcer healing and reducing infection compared to traditional dressing changes and other offloading methods, reporting a 91% healing rate within the TCC population, compared to a 32% rate of healing in the control group (19).

Advanced Wound Care Techniques and Dressings

Wound dressings are the most basic and common treatment method for DFUs. However, research has found that adding other methods has proven vastly more effective than wound dressings alone (19).

Treatment/Dressing Method |

Pros |

Cons |

Is it ideal for infected chronic wounds? |

| Gauze | Highly absorbent | May cause wound trauma and pain upon removal | No, but it can halt minimal bacteria load |

| Inexpensive | Nonocclusive | ||

| Readily available | Bacteria can permeate | ||

| Transparent films | Flexible | No control over exudate | Not to be used for infected wounds, it provides an ideal moist environment for bacteria to proliferate. |

| Permeable to water, oxygen, and carbon dioxide | |||

| Impermeable to bacteria | |||

| Promote autolytic debridement | |||

| Foam dressings | Allow gaseous exchange | Able to dry wounds fast | It can be used to treat infection if changed daily |

| Can absorb wound drainage | |||

| Hydrogels | High water content aids granulation | Exudate accumulation | It has been used to treat chronic wounds but is not ideal for treating chronic infections. |

| Easy application and removal | Maceration leads to bacterial proliferation. | ||

| Non‐toxic | Low mechanical strength | ||

| pH-sensitive dressings | It can be incorporated into hydrogels | Suffers from high mechanical fragility | Yes |

| Creates a conformational change when a change in pH is detected | Fouling by non‐specific absorption | ||

| Releases antimicrobials | It needs to be frequently calibrated. | ||

| Silver dressings | Traditional | Lack of evidence on pathogens that have invaded deep into the tissue | Yes |

| Broad spectrum antibiotic | |||

| Reduces inflammation in the wound | |||

| Alginate film with xylitol or gentamycin | Superior mechanical properties | Inhibit keratinocyte migration | Yes |

| Rheological properties and effective against bacteria that produce biofilm | |||

| Microspheres | Can encapsulate multiple drugs at once | They can potentially possibly migrate from the site of injection and cause organ damage. | Yes |

(17)

Infection Control

The use of systemic and local antibiotics is a non-invasive treatment for DFU. Antibiotics can be administered topically through sponge or gauze applications or with a circulator boot (19).

Most DFUs have a microbial cause, with aerobic Gram-positive cocci and staphylococci being the most common implicated microbes (19). Ulcers without any signs of infection typically do not require antibiotic therapy.

If the wound is infected, a post-debridement specimen must be collected for aerobic and anaerobic cultures. If necessary, imaging can include radiographs and MRIs.

Antibiotics may be prescribed. If the infection is mild or moderate, narrow-spectrum oral antibiotics may be appropriate. If the infection severity is moderate, high, or severe, a broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotic should be used (19).

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT)

One of the most compelling developments in DFU treatment is negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), commonly called a “wound vac.” NPWT utilizes vacuum pressure to draw fluid from the wound and increase blood flow to the affected area to stimulate and support the healing process. NPWT stimulates blood flow and promotes a wound-healing cascade that includes tissue granulation, vessel proliferation, angiogenesis, epithelialization, and excess extracellular fluid removal (19).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you describe the ” offloading ” process in managing DFUs?

- Why are revascularization methods more important than removing pressure in cases of impaired vascularity?

- How does negative-pressure wound therapy promote wound healing?

- What are the most common microbes identified in DFUs?

Debridement

Debridement is the medical procedure of removing dead, damaged, or infected tissue from a wound to promote healing and reduce the risk of infection. By eliminating necrotic tissue and biofilms, debridement creates an environment conducive to healing and helps stimulate healthy tissue growth.

Revascularization

If patients with foot ulcers also have peripheral arterial disease (PAD), it is more likely that delayed healing and potential amputation may be observed (19). In these cases of ischemia, revascularization can serve as a promising treatment option.

According to various studies, the ulcer healing rate following revascularization ranges from 46% to 91%, representing a higher healing rate than PAD patients who do not undergo revascularization (19).

If other interventions are not possible, revascularization may incorporate stenting and surgical bypass. Atherectomy, shockwave treatment for calcified lesions, and balloon revascularization can also be used alone or with stenting.

Major assessment considerations for this therapy include close monitoring of glucose, lipids, and blood pressure and the use of antiplatelet therapy following the surgical procedure; statin drugs are recommended and proven to stabilize any plaques present before and after revascularization (19).

Skin grafting

Skin grafting may serve as a solution when DFUs become more severe. It attempts to replace the infected skin and promote the healing process. A variety of skin grafting techniques may be used, including bioengineered or artificial skin, autografts taken from the patient, or xenografts (taken from animals) (19).

Amputation

Amputation represents the final management option when treating DFU and is reserved for the most chronic levels of infection or deformity that render the foot nonfunctional (19).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you describe debriding procedures and their purpose in wound management?

- What are the familiar sources of skin grafts for nonhealing DFUs?

- Why is amputation reserved for more chronic and critical wounds?

- How would amputation impact the other various pressure points of the body?

Emerging Therapies

The use of growth factors, skin substitutes, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, larvae therapy, and other various methods have proven effective in managing DFUs. Below are examples of these:

- Human skin equivalent (HSE)

- HSE is more effective than the standard treatment of saline-moistened gauze in reducing the rates of amputation and infection and improving the ulcer healing rate (19).

- Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT)

- Systemic hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) is reserved for advanced cases and aims to reduce the risk of amputation (19).

- Larvae therapy (maggot therapy)

- This is another well-researched technique concerning the treatment of chronic wounds in which maggots are placed on the wound area to remove dead tissue and encourage the development of granulation tissue (16)

- Topical growth factors

- Topical growth factors, particularly platelet-derived growth factors, have also proven effective in increasing ulcer healing (19).

- Extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT)

- ESWT has been shown to accelerate the healing of soft tissue wounds and is utilized to stimulate osteoblasts and facilitate soft tissue healing (19).

- Stem cell therapy

- Stem cells aid wound healing by secreting cytokines that play important roles in cell migration, angiogenesis, remodeling of the extracellular matrix, and nerve regeneration (16, 19).

Nursing Considerations

Nursing considerations for DFUs should focus on addressing the underlying problem. Building your initial and follow-up assessment documentation and management workflows is essential.

Consider the following approaches upon initial assessment of DFUs:

- Relieve pressure and consider offloading devices

- Assess and manage infections

- Capture manual or digital wound measurements.

- Evaluate surgical procedure based on duration of wound and patient presentation

- Assist in debriding procedures, providing significant patient education on the procedures and their purpose.

- Optimize nutrition for wound healing and glucose control.

- Protect the surrounding tissue of the wound.

- Control moisture and provide dressing products that maintain a moist wound bed, control exudate, and avoid maceration of surrounding intact skin.

- Provide patient education and assess patient/caregiver understanding of the treatment plan.

- Assess circulation and consider perfusion assessment testing

- Consider alternative technologies for wound management

- Research and understand growth factors and/or cellular- and tissue-based products

- Improve microcirculation by use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy based on clinical requirements.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What underlying mechanisms make diabetic patients more susceptible to developing foot ulcers, and how can nurses explain this to patients in simple terms?

- When assessing a patient with diabetes, what signs and symptoms should alert me to the possibility of a developing foot ulcer?

- What are the key components of evidence-based wound care for DFUs, and how can you ensure their implementation in practice?

- What strategies can nurses use to educate patients on proper foot care and preventing foot ulcers in a way that resonates with their daily lives?

Screening and Prevention

Prevention and management of diabetic foot complications are critical to diabetes care.

ADA’s Treatment Recommendations for Neuropathy (1)

- Optimize glucose management to prevent or delay the development of neuropathy

- Optimize blood pressure and serum lipid control to reduce the risk or slow the progression of diabetic neuropathy.

- Dyslipidemia is a significant factor in the development of neuropathy in people with diabetes (1).

- Assess and treat diabetic peripheral neuropathy pain.

- Gabapentinoids, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and sodium channel blockers are recommended as initial pharmacologic treatments for neuropathic pain in diabetes.

Appropriate, well-fitted athletic or walking shoes with customized pressure-relieving orthotic inserts should be used for plantar pressures or deformities such as bunions. Those with even more significant deformities, such as Charcot joint disease, may require custom-made footwear (1).

Foot Exams

Frequent foot exams are fundamental to decreasing incidence and morbidity. Guidelines for the frequency of screening for PN, PAD, and DFU or other pre-ulcerative lesions in adults with diabetes recommend at least an annual comprehensive foot exam for all patients with diabetes, including inspection, monofilament, tuning fork evaluation for loss of protective sensation, and pulse exam (1). Screening exams should be performed every 3–6 months for high-risk patients (1).

Emerging Modalities for Self-Screening and Early Detection of DFU

Several promising technologies may aid in the early detection of ulcerative or ulcerative foot lesions.

Telemedicine-assisted foot examinations can be effective for detecting early lesions, with time and cost savings for patients that promise to reduce existing barriers to care (19).

Increased temperature is a well-validated warning sign for DFUs, and clinical trials of temperature-sensing mats and socks have successfully identified pre-ulcer or DFU weeks earlier than a clinical exam (19).

Plantar pressure-based monitoring is a newer technology that recognizes pressure points at risk for breakdown. An in-shoe plantar pressure system is suggested to be a feasible solution to evaluating physical activity, measuring dynamic plantar pressures during walking to calculate peak plantar pressures (PPP) and other associated parameters, which are significantly independent risk factors of DFUs (11).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How can nurses advocate for ensuring continuity of care for patients with chronic wounds or a history of foot ulcers?

- Can you describe ways to motivate and encourage patients to adhere to lifestyle changes that promote glycemic control?

- Are you familiar with evidence-based guidelines and resources on general diabetes management?

- Do you notice any gaps in your knowledge or skills related to DFU management, and how can you address them through continued learning?

Conclusion

Managing diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) is not just about treating wounds—it’s about recognizing risk factors, preventing complications, preserving mobility, and enhancing the quality of life for individuals with diabetes. This course has provided learners with a comprehensive understanding of the pathophysiology, risk factors, classification systems, and evidence-based treatment strategies for DFUs. From recognizing the critical role of offloading and advanced wound care techniques to addressing the socioeconomic factors that impact outcomes, learners are now equipped to deliver holistic, patient-centered care.

It is meaningful to stay informed on the latest guidelines, as evidence-based practice guidelines and innovations are constantly developing. Fostering interprofessional collaboration and empowering patients through education is also vital to turning a minor wound into a story of recovery and resilience.

References + Disclaimer

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. (2024). Retinopathy, Neuropathy, and Foot Care: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 1 January 2024; 47 (Supplement_1): S231–S243. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc24-S012

- Bates-Jensen, B.M. (2021). Assessment of a patient with a wound. McNichol, L., Ratliff, C., & Yates, S. (2021). In Wound, ostomy, and continence nurses society core curriculum: Wound management. Wolters Kluwer Health.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2024). Data & research on diabetes. Retrieved November 18, 2024, from https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/php/data-research/index.html

- Cerqueira, L.O., Duarte, E.G., Barros, A.L.S, Cerqueira, J.R., de Araújo, W.J.B. (2020). WIfI classification: the Society for Vascular Surgery lower extremity threatened limb classification system, a literature review. J Vasc Bras. 2020 May 8;19:e20190070. Doi: 10.1590/1677-5449.190070. PMID: 34178056; PMCID: PMC8202158.

- Dai, J., Jiang, C., Chen, H., et al. (2019). Vitamin D and diabetic foot ulcer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition & Diabetes, 9 (1), 8. doi: 10.1038/s41387-019-0078-9.

- Das, S.K., Roy, P., Singh, P., Diwakar, M., Singh, V., Maurya, A., Kumar, S., Kadry, S., & Kim, J. (2023). Diabetic Foot Ulcer Identification: A Review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023 Jun 7;13(12):1998. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics13121998. PMID: 37370893; PMCID: PMC10297618.

- Fitridge, R., Chuter, V., Mills, J., van den Berg, J.C., Venermo, M., Schaper, N. et al., (2023). The intersocietal IWGDF, ESVS, SVS guidelines on peripheral artery disease in people with diabetes mellitus and a foot ulcer. Journal of Vascular Surgery, 78(5), 1101–1131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2023.08.012

- Foad, A.F.A. (2021). Acute and Chronic Wound Healing Physiology. In: Zubair, M., Ahmad, J., Malik, A., Talluri, M.R. (eds) Diabetic Foot Ulcer. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-7639-3_4

- Gamage C., Wijesinghe I., Perera I. Automatic Scoring of Diabetic Foot Ulcers through Deep CNN Based Feature Extraction with Low-Rank Matrix Factorization; Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 19th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Bioengineering (BIBE); Athens, Greece. 28–30 October 2019; pp. 352–356.

- Healthy People 2030, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2020). Social determinants of health (SDOH). Retrieved from https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

- Lung, C.-W., Wu, F.-L., Liao, F., Pu, F., Fan, Y., & Jan, Y.-K. (2020). Emerging technologies for the prevention and management of diabetic foot ulcers. Journal of Tissue Viability., 29(2), 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtv.2020.03.003

- Mauricio, D., & Alonso, N. (Eds.). (2024). Chronic Complications of Diabetes Mellitus : Current Outlook and Novel Pathophysiological Insights. Academic Press.

- McDermott, K., Fang, M., Boulton, A.J.M, Selvin, E., & Hicks, C.W. (2023). Etiology, Epidemiology, and Disparities in the Burden of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Diabetes Care 2 January 2023; 46 (1): 209–221. https://doi.org/10.2337/dci22-0043

- McNichol, L., Ratliff, C., & Yates, S. (2021). Wound, ostomy, and continence nurses society core curriculum: Wound management. Wolters Kluwer Health.

- Mufti, A., Maliyar, K., Ayello, E.A., and Sibbald, R.G. (2021). Anatomy and physiology of the skin. In McNichol, L., Wound, O., Ratliff, C., Yates, S., & Wound, O. (2021). Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nurses Society core curriculum: wound management (Second edition.). (pp. 46-94). Wolters Kluwer Health.

- Nather, A. (Ed.). (2023). Understanding diabetic foot: a comprehensive guide for general practitioners. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.

- Norton P, Trus P, Wang F, Thornton MJ, Chang CY. Understanding and treating diabetic foot ulcers: Insights into the role of cutaneous microbiota and innovative therapies. Skin Health Dis. 2024 May 30;4(4):e399. Doi: 10.1002/ski2.399. PMID: 39104636; PMCID: PMC11297444.

- Ogurtsova K., Guariguata L., Barengo N.C., Ruiz P.L.-D., Sacre J.W., Karuranga S., Sun H., Boyko E.J., Magliano D.J. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of undiagnosed diabetes in adults for 2021. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022;183:109118. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109118.

- Raja J.M., Maturana M.A., Kayali S., Khouzam A., & Efeovbokhan, N. (2023). Diabetic foot ulcer: A comprehensive review of pathophysiology and management modalities. World J Clin Cases. 2023 Mar 16;11(8):1684-1693. Doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i8.1684. PMID: 36970004; PMCID: PMC10037283.

- Vera-Cruz, P.N., Palmes, P.P., Tonogan, L., Troncillo, A.H. (2020). Comparison of WIFi, University of Texas and Wagner Classification Systems as Major Amputation Predictors for Admitted Diabetic Foot Patients: A Prospective Cohort Study. Malays Orthop J. 2020 Nov;14(3):114-123. doi: 10.5704/MOJ.2011.018. PMID: 33403071; PMCID: PMC7751999.

- Voelker, R. (2023). What are diabetic foot ulcers? JAMA. 2023;330(23):2314. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.17291

- Wang X, Luo L, Xing J, Wang J, Shi B, Li YM, Li YG. Assessment of peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes by diffusion tensor imaging. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2022 Jan;12(1):395-405. Doi: 10.21037/qims-21-126. PMID: 34993088; PMCID: PMC8666762.

- [Image] Moore, J. (2009). CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Neuropathic_heel_ulcer.jpg)

- [Image] Moore, J. (2006). CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arterial_ulcer_peripheral_vascular_disease.jpg

- [Image] Dreyer, M.A. (2020). Diabetic foot ulcer. CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Diabetic_Foot_Ulcer.jpg)

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate