Flap Surgery: The Basics

Contact Hours: 2

Author(s):

Abbie Schmitt MSN, RN

Course Highlights

- In this Flap Surgery: The Basics course, we will learn about examples of indications for flap surgery.

- You’ll also learn the risks and benefits of various flap surgeries.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of prevention and management strategies for flap dehiscence or loss of viability.

Introduction

Flap surgeries can be a critical treatment for various wounds to provide bulk tissue. It is a tad more detailed than skin grafts, as it involves a circulatory supply from the donor to the recipient sites. It is important to recognize what flap surgery entails, the indications, and the types of flap surgeries. Nurses should be knowledgeable about care plans and assessment for flap surgery, positioning techniques, patient education topics, and how to identify possible complications such as infection or flap dehiscence. Are you ready to dive into the interesting course topic of flap surgery?

Flap Surgery: What is it?

Flap surgery involves removing healthy, live tissue from one location of the body and transporting it to another area that needs it for healing. Flap surgeries are commonly used to transfer this healthy tissue to areas of lost skin, fat, muscle movement, and/or skeletal support (9). A tissue flap has its system for vascularization and does not depend on the recipient’s wound bed to perfuse the donor tissue, which differs from non-vascularized skin grafts (8). A flap is tissue with a substantial blood supply transferred from a donor to a recipient site. If the flap surgery was a party, the damaged host site would send an invite saying, “BYOB- Bring Your Blood-Supply!”

The flap continues to be fed by the same blood supply from where it was taken until new blood vessels grow from the recipient site and the wound heals completely. The recipient site is called the primary defect , and the wound created by cutting, lifting, or sliding the flap to fill the primary defect is called the secondary defect (8). The flap’s base, or pedicle, is the tissue that remains attached to the skin adjacent to the defect and contains the vascular supply required for initial flap survival (8).

Surgeons have used skin flaps to repair wounds and tissue damage for centuries. The term “flap” was derived from the Dutch word “flappe” during the 16th century (8). Around 700 B.C., the Sushruta Samhita (an ancient text on surgery and medicine) first documented a technique of reconstructing a significant nasal tip defect with a flap of cheek tissue (8). New methods are constantly being developed to meet various needs. Flap surgeries are used for a variety of wounds, from pressure ulcers to breast reconstruction following mastectomy.

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever cared for a patient following a flap surgery?

- Do you recognize the difference between flap surgery and skin grafting?

- Are you familiar with the vascular structure at deeper skin levels?

- Can you discuss how significant improvements could have been made over hundreds of years?

Types of Flap Surgeries

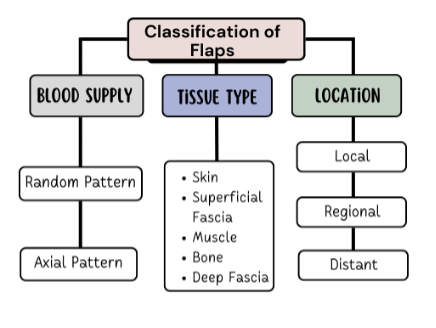

Flap surgeries are classified in the following ways: (9)

- Blood supply

- Type/composition of tissue

- Distance of the healthy site from the recipient tissue

- Locations of donor and recipient tissue

- Movement

Figure 1: Classification of Flaps

Classification by Blood Supply

Flaps can be named based on the supply of blood. Understanding blood circulation to the donor tissue is critical when describing the flap type. The terms random and axial are used to categorize the blood supply.

- Random Flaps

- Not based on a specific vessel.

- Uses subdermal plexuses (network of blood vessels between the deep reticular portion of the dermis and subcutaneous fat tissue beneath it) (7)

- Axial Flaps

- Single, direct cutaneous artery in the axis of the flap

- Named according to the pathway

Classification by Tissue Type

Flaps can be named according to their composition. The tissue composition may be skin, fascia, muscle, bone, nerve, cartilage, or a combination. Fascia is the thin lining of connective tissue that surrounds and holds each blood vessel, bone, nerve fiber, and muscle in place (7). Cutaneous refers to the layers of skin. Pedicle flaps are those that are still attached to the original site, and the other end is moved to cover the recipient area; a free flap is an area of tissue completely removed from one part of the body and surgically placed in another location (8).

Common flaps: (5)

- Skin Flap: Skin and superficial fascia

- Fascio-cutaneous Flap: Skin and deeper layer of deep fascia

- Fascial Flap: Deep fascia only

- Muscle Flap: Muscle only

- Myo-cutaneous Flap: Muscle and skin

- Osteomyocutaneous Flap: Muscle, bone, and skin

- Bone Flaps: Bone (vascularized)

- Innervated Flaps: Flaps that contain a motor or sensory nerve and function

Fascio-cutaneous Flap

This flap includes the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and the underlying deep fascia (5). The musculocutaneous perforators or direct septocutaneous branches of major arteries act as the vascular supply (5). Perforator flaps are named based on location, arterial supply, or the muscle of origin. The indications for fasciocutaneous flaps are based on their advantages of being simpler, reliable, thin, and easily mobilized (8). These flaps can come from many potential donor sites (8).

Muscle Flap

Muscle tissue can be used as donor tissue in flap surgery. Surgeons may utilize the benefits of flap surgery in wound closure following major surgeries. For example, median sternotomy (vertical inline incision through the sternum of the chest) is the most commonly used approach for cardiac surgery (6). Cardiac surgeons face the risk of deep sternal wound infections following surgery, which is associated with significant morbidity and mortality rates. The use of soft tissue flaps for sternal closure is helpful for patients with extensive tissue deficits after debridement (6). It can be used for immediate or delayed closure. Options for donor tissue for sternal flap closure include the pectoralis major, rectus abdominis, latissimus dorsi muscles, or an omental flap (6).

Remember, flaps are transplanted with blood supply intact, so it’s essential to know the supply. For instance, if tissue from the pectoralis major muscle is used, the nurse must recognize that this muscle’s primary and secondary blood supply is the thoracoacromial artery and perforators from the internal mammary artery (6).

Musculocutaneous Flap

This type of flap, which includes muscle and skin layers, is often used when the area to be covered needs more bulk and an increased blood supply. Musculocutaneous flap surgery is frequently used to rebuild a breast after a mastectomy (5).

Bone Flap

A bone flap is comprised of bone with a vascular supply. An example of this flap surgery is for a surgical site infection (SSI) following a craniotomy; in this procedure, operative debridement occurs, and the bone flap is removed, cleaned, and replaced (4). An alternate therapy for this is titanium cranioplasty (implant instead of native bone flap), which has similar outcomes.

Classification by Location and Movement

- Local flap: Donor tissue is located next to the area receiving the tissue; the skin remains attached at one end, allowing the blood supply to be left intact (5).

- Regional flap: Donor tissue is a section attached by a specific blood vessel.

- Distant flap: Donor and recipient tissues are distally located from each other. This flap surgery involves detaching and reattaching skin and blood vessels from one body site to another; microsurgery is used to connect the blood vessels (5).

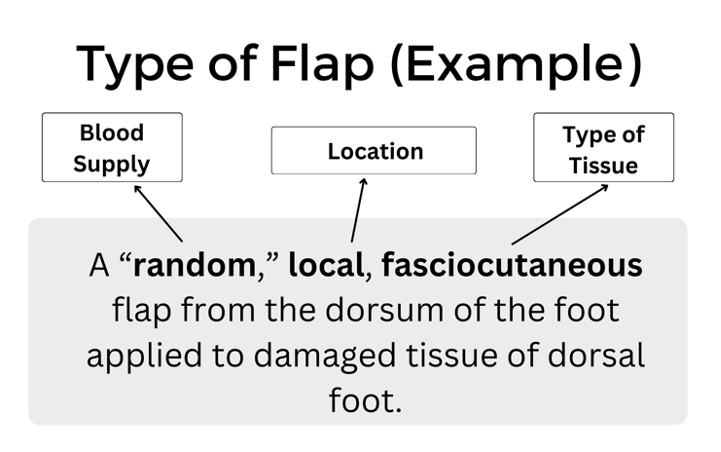

Figure 2: Example of Flap Type

The movement of the flap is also used to describe flap surgery. You may hear advancement, sliding, rotation, and pivotal terms. Sliding flaps is when the tissue is moved or “slid” directly into the adjacent defect without “jumping” over other tissue (5). Advancement flaps are considered simple movements for local flaps and fall within the group of sliding flaps. Pivotal (geometric) flaps include rotation, transposition, and interpolation (5). Local, random pattern flaps are common for the reconstruction of cutaneous defects.

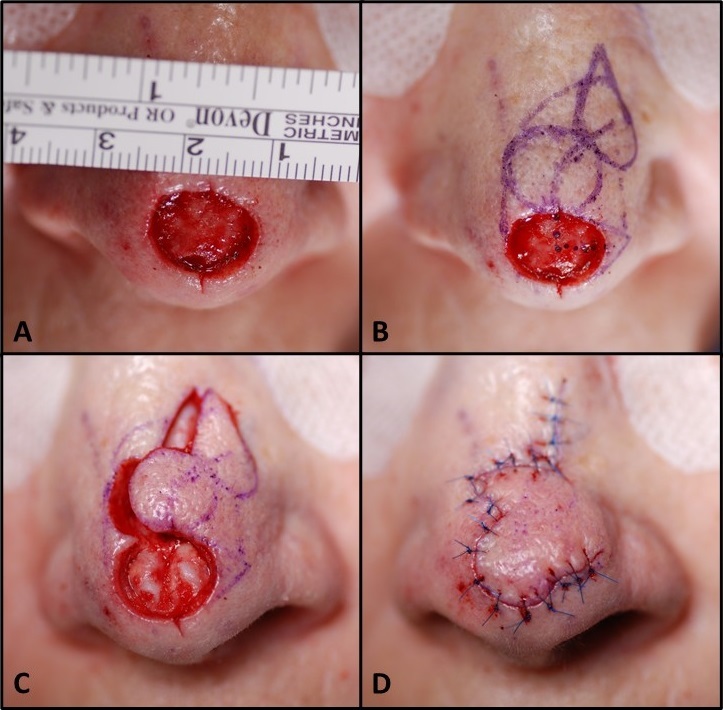

Image 1: Image of a local flap surgical procedure to cover a nasal tip defect/wound (9)

Ask yourself...

- Are you familiar with the differences in skin, muscular, bone, and nerve tissue?

- Can you think of the benefits of using a local, pedicle flap over a free flap?

- Can you discuss how fasciocutaneous flaps may have more advantages and potential donor sites?

- Can you recognize the general location and complexity of a surgical note that says “local, random, skin flap with pivotal manipulation at midline of forehead”?

Indications for Surgery

There is an incredible breadth of possibilities for flap reconstructive surgery, from minor, skin-only defects to significant, multi-tissue defects. There is a wide range of etiologies, such as traumatic, oncological, and congenital (9). The transferred tissue flap can contain multiple tissue types, including skin, muscle, nerve, fascia, and bone (9). The larger the tissue volume transferred, the greater the need for perfusion. A typical indication is the need for a large bulk of tissue. Flaps are helpful when wounds are large, complex, or need large amounts of tissue for closure.

General Indications:

- Protection of the greater vessels

- Correction of a congenital defect

- Abdominal wall reconstruction

- Deep, gaping wounds

- Reconstruction after tumor excision

- Trauma

- Debridement procedure to remove infected or necrotic tissue

- Venous ulcers (non-healing)

- Pressure ulcers (non-healing)

- Breast reconstruction

- Rhinoplasty

- Scar Revision

- Skin Cancer

- Burns

Each type of wound has unique indications. Skin flap surgery is commonly required when a wound is too big for the edges to be brought together directly, so the flap covers the area and depth of the wound (10).

Ask yourself...

- Do you have experience caring for a patient with a deep, healing wound?

- Have you ever cared for a patient following a tumor removal?

- Can you discuss why debridement of the recipient site is essential before flap placement?

- Can you name various methods of wound closure? (ex: sutures)

Risks versus Benefits

Flap survival depends on factors of blood flow, angiogenesis (formation of new blood cells), vascularization, edema, wound closure tension, postoperative complications (hematoma/seromas), and infection (8). Before the initial incision, the flap is fully vascularized and viable, but once the flap is raised, it is immediately ischemic. The tissue can survive up to 12 to 13 hours of avascularity at 37°F; many research studies have proven it is even longer viable (8). This time is invaluable for preserving the tissue. Sufficient blood flow through the attachment of the base of the flap is essential in the initial 24 to 48 hours after surgery (8). There is a risk of tissue loss with no meaningful contribution to the needed area, along with a new wound. This risk reminds me of a neighbor who once removed carpet from a closet to patch carpet in a bedroom, only to find the cut was too small and they were left with two gaping carpet holes.

There is also a risk of bleeding, infection, or necrosis at both sites. A recent study found that more than 27% of patients will experience a minor complication (wound dehiscence, infection, fistula, and donor-site problems) after surgery, and 6% of patients will suffer a major complication (flap failure, pneumonia, and cerebrovascular accidents) following surgery (11). Chronic flap complications can also be aesthetic, including scarring, contracture, color/texture mismatch, and lack of hair growth. Patients may experience pain or numbness at the sites on a chronic basis as well (9).

Most flap surgeries are considered safe with a low complication rate, and surgeons report that flap surgery is not avoidable in certain circumstances. However, the surgery preparation itself and anesthesia present considerations for elderly patients or those with heart disease, uncontrolled diabetes, smokers, or bleeding disorders (2). Nutrition is a key factor in these surgical procedures. Poor nutritional status has been linked with greater adverse outcomes (11). The healthier the patient is before surgery, the lower the chances of complications, so glucose control and weight management are examples of risk reduction strategies.

Ask yourself...

- Do you feel confident with patient education methods for explaining risks versus benefits?

- Can you name reasons why informed consent for flap procedures is required and why it is ethical?

- Do you have experience educating patients on diabetes and the importance of glucose control in wound healing?

- Are you familiar with your facility’s medical literature database?

Preparing for Surgery

Patients undergoing flap surgery need abundant education on what to expect throughout this procedure. There are many opportunities to optimize patient outcomes before going to the operating room. Preoperative education, for example, has been suggested to have a significant, positive effect on clinical outcomes (11). Many patients are also experiencing other issues, such as cancer diagnoses, poor circulation, comorbidities, and bed sores, among others. Taking time to prepare each patient holistically is essential.

Addressing Comorbidities and Other Conditions

Multiple studies have found an increased surgical complication rate in patients with diabetes mellitus, older age, female gender, malnutrition, anemia, and nicotine intake (11). Before surgery, the goal is to improve and optimize the modifiable conditions as much as possible, for instance, nicotine reduction, glucose control, and anemia. Further, patients with advanced cancer can have hypothyroidism affecting postoperative healing if left uncorrected (11). Non-modifiable factors such as a history of radiotherapy, age, advanced cancer stage, or chronic kidney disease, cannot be altered before surgery, but can guide care planning and education following the surgery.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that adequate nutrition before and after flap surgery improves outcomes. An estimated 35% of patients with head and neck cancers present in a state of malnutrition, and the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommends that all patients undergo a comprehensive preoperative nutritional assessment and consult with a nutritionist (11). Improved nutrition status can hopefully yield enhanced wound healing and a reduction in the risk of infection.

Lab assessment is key to preparation before flap surgery. An example is an assessment for anemia before surgery. Patients who are anemic at the time of free flap surgery have been found to have poor outcomes (11). Remember, hemoglobin transporting the oxygen to the sites of flap insertion and removal is vital to the survival of the flap. Preoperative hemoglobin values below 10 g/dL have historically been a significant predictor of flap failure and thrombosis (11). A hematocrit level of 30 to 40% with normovolemic hemodilution is ideal to optimize patient outcomes.

Blood transfusions during or following surgery impact flap success as well. Transfusion can increase blood viscosity and immunosuppression, thus leading to decreased blood flow and flap compromise from poor perfusion (11). Studies also show a link between blood transfusions and increased wound infections (11). Before surgery, steps and treatments should be taken to improve anemia or blood component abnormalities and give these patients a greater chance for successful flap surgery.

Preoperative considerations should include: (9)

- Patient age

- Diabetes status

- Smoking history

- Atherosclerosis

- Peripheral vascular disease

- Steroid use

- Previous surgeries

- The extent and location of the defect

Providing Preoperative Instructions

A lack of education, difficulty in understanding complex medical information, fear and anxiety about the surgery, and language barriers are some of the challenges a patient undergoing surgery may have. Patients may also have limited access to reliable health resources or be unable to recall important information due to stress or preoperative medications. As a result, they may not be fully informed about the surgical process, potential risks, and postoperative care.

Preoperative education list:

- Assess the patient’s level of understanding.

- Each facility should have a preoperative teaching program with specific content on surgery, but you must assess if the patient understands this information.

- Review specific pathology and anticipated surgical procedure.

- Verify that consent has been obtained/signed.

- Informed surgical choices and consent are required, not only a signature.

- Use resource teaching materials and audiovisuals on flap surgery and implement an individualized preoperative teaching plan.

- Preoperative or postoperative procedures and expectations, output (urinary and bowel) changes to expect following surgery, dietary considerations, anticipated intravenous (IV) lines and tubes (nasogastric [NG] tubes, drains, and catheters).

- Preoperative instructions: NPO guidance before surgery, shower or skin preparation, medications to take and hold, prophylactic antibiotics or anticoagulants, anesthesia premedication.

- Discuss the postoperative pain management plan and options.

- Some patients may expect to be pain-free or are hesitant to take narcotic agents.

- Provide education and encourage the practice of coughing and deep breathing.

- Confirm and recheck the surgery schedule, patient identification band, chart, and signed operative consent for the surgical procedure.

- Offer pastoral spiritual care or counseling.

Ask yourself...

- What are some examples of pertinent laboratory values to assess before surgery?

- What are the normal values of hemoglobin and hematocrit?

- Do you consider pain management a “one size fits all” care plan?

- Are you familiar with your organization’s pastoral and spiritual counselors and supportive resources?

Post-Operative Considerations

This section will cover assessment, drains, positioning, and negative pressure wound therapy during the post-operative period.

Assessment

Frequent monitoring of free flaps in the acute postoperative period is essential. It is strongly recommended that flap assessments be performed at least hourly for the first 24 hours postoperatively and then continued at a reduced increment for the duration of the patient’s hospitalization (11). Each facility should have standing orders for flap assessment based on the surgeon’s or regulatory body’s directive.

In addition to conventional assessments of flaps (physical exam of flap warmth, turgor, capillary refill, color, and Doppler assessment of the vascular pedicle), many adjuncts have been developed, including implantable Dopplers to assess blood flow (11). Assessments should include a head-to-toe physical assessment and a focused wound assessment. A focused cardiovascular (circulation and perfusion) and integumentary evaluation is appropriate. Review of lab work, indicative of healing status, hemodynamics, and infection, should be a priority. Standard post-operative assessments following anesthesia, such as respiratory and orientation, should follow facility protocol.

Assess the circulation of the flap:

- Color of the flap (dusky, blue, pink, pale)

- Warmth

- Dry/Intact? Leaking Fluids?

- Changes in size

- Edema

- Indications of hematoma (sutures over the flap pulling apart, or palpable crepitus beneath the skin)

Assess amount and type of exudate (drainage): (3)

- Amount (scant, small/minimal, moderate, or large/copious)

- Color and thickness: (7)

- Sanguineous: fresh bleeding

- Serous: clear, thin, watery plasma

- Serosanguinous: serous drainage with small amounts of blood noted

- Purulent: thick and opaque; color can be tan, yellow, green, or brown (this is an abnormal finding and should be reported to the physician or wound care provider)

Use of Doppler to assess deeper circulation of flap: (11)

- Color duplex ultrasound

- Near-infrared spectroscopy

- LASER Doppler flowmetry

- Implantable Doppler (useful for buried flaps)

Assess circulation distal to the flap:

- Capillary refill

- Color

- Temperature

- Pulses

- Edema

Drains

Drains may be used to remove fluid around the donor and recipient surgical areas to enhance healing (7).

Patients may have the following drains after flap surgery:

- Jackson Pratt (JP) drains

- JP drains are closed-suction devices that remove fluids from the surgical sites.

- JP drains contain a flexible bulb with a plug that can be opened to remove collected fluid.

- Each time fluid is removed from the JP drain, the nurse should squeeze the air out of the bulb and replace the plug before releasing the bulb.

- This suction creates a vacuum that pulls fluid into the drainage tubing and bulb.

- Penrose drains:

- A Penrose drain is a soft, flexible tube inserted into the surgical site that drains fluid away from the wound bed (7).

- Nurses should assess the drain and express fluid when appropriate to prevent accumulation.

Positioning

Positioning following flap surgery aims to promote and improve tissue perfusion. Positioning and elevation of the flap recipient will promote venous return and reduce fluid accumulation to improve tissue perfusion. Activity, exercise, and repositioning improve tissue perfusion. Massage of the erythematous area is avoided because damage to the capillaries and deep tissue may occur (10). Patients should never lie on the wound, and extremities should “dangle” (if the donor or recipient site is on the extremities). Positioning may require creativity when there are multiple drains, NG tubes, wound therapy devices, IV tubes, and dressings. Positioning should be free of restrictive clothing, and flap sites should be visible to assess dressings. The surrounding skin must be sanitary and free of debris.

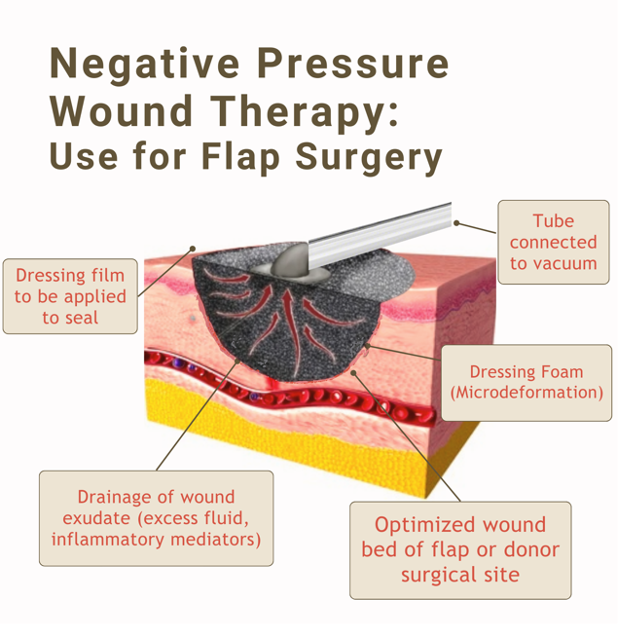

Negative Pressure Wound Therapy

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) is typically used for soft-tissue salvage after the development of complications after flap surgery. For example, NPWT may be applied if an infection occurs in the donor or recipient flap. Immediate postoperative application of NPWT over the flap coverage is not standard (2). However, nurses should be aware of this treatment, its application, and its mechanisms of action.

NPWT is also known as a wound vac. NPWT uses sub-atmospheric pressure to help reduce inflammatory exudate and promote granulation tissue to enhance wound healing (4). The idea of applying negative pressure therapy is that once the pressure is lower around the wound, the gentle vacuum suction can lift fluid and debris away and give the wound a fighting chance to heal naturally. NPWT systems include a sterile foam sponge applied to the wound bed, a semi-occlusive adhesive cover, a fluid collection system or cannister, and the suction pump (1). The foam sponge is applied to the wound and covered. A fenestrated tube is embedded in the foam, the wound is sealed with adhesive tape to make it airtight, and the machine delivers continuous or intermittent suction, ranging from 50 to 125 mmHg (1).

Figure 3. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy Visual

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever completed a focused wound assessment that resulted in abnormal findings that were anticipated?

- Can you name examples of pertinent laboratory values to assess following general surgery?

- Have you ever used or witnessed the use of a Doppler in the assessment of proper circulation?

- Can you describe the importance of positioning in tissue perfusion?

Home Care and Patient Education

Educating clients and caregivers about wound care and skin integrity empowers them to care for their flap sites actively. With proper wound cleaning, dressing changes, and preventive measures, individuals can confidently perform self-care and enhance healing. Pamphlets, printouts, websites, and referrals to specialists will give the patients a stronger foundation of knowledge.

- Wound Assessment

- Teach the patient and caregiver about skin and wound assessment, ways to monitor for signs and symptoms of infection, complications, and proper healing.

- Signs of Infection

- Signs of a localized wound infection include redness, warmth, tenderness, and abnormal purulent drainage around the wound.

- Importance of proper nutrition, hydration, and methods to maintain tissue integrity

- Adequate caloric intake and a balance of protein and essential vitamins have been shown to improve flap healing (3).

- Dressing changes, wound cleansing, and hand hygiene

- Methods to prevent skin breakdown

- Flap surgery is often used to treat a deep pressure wound, so education is needed on impaired skin integrity due to friction.

- Common areas: Sacrum, heels, and elbows.

- Avoid raising the head of the bed often, causing weight to be applied to the sacrum.

- Importance of turning, mobility, and ambulation

- Pain management

- Medications

- Heat/cold therapy applications and precautions

- Negative Pressure Wound Therapy Devices (wound vac)

- Home healthcare is applicable for these devices and should be changed by a certified individual, but patients should be aware of basic care and troubleshooting.

- Drain maintenance

- Showering restrictions

- Reduction of stress and tension at the wound site

- Avoid constipation, strenuous movements, and lifting

- Restrictions vary for the location of flaps, and per the surgeon’s instructions

- Follow-up appointments

Ask yourself...

- Can you describe assessment findings that indicate infection after flap surgery?

- Are you familiar with various drains, such as JP drains?

- What do you think are some fears among patients going home or to a long-term care facility after flap surgery

Flap Dehiscence or Loss

Flap dehiscence is a complication in which the incision made to either the donor or recipient site reopens. A flap loss refers to the flap not re-establishing blood flow and surviving, leading to tissue necrosis. As we mentioned earlier, the flap’s survival is impacted by blood flow, new vascularization and tissue formation, edema, wound closure tension, postoperative complications (hematoma/seromas), and infection (8).

Prevention Strategies

Nurses should apply their basic knowledge of the causes of wound dehiscence. Factors that influence dehiscence risk include the ability to synthesize collagen, the strength of suture material, closure technique, and stress on the incision, such as coughing, strenuous movement, or obesity (7). Consider areas that have greater stress and tension, such as the abdomen. Dehiscence is most common following abdominal flap surgeries (7). NPWT is a great preventative measure for wound dehiscence, as studies found a roughly 50% reduction in stress and tension at the incision site with its use (7). This stress reduction is attributed to decreased subcutaneous fluid accumulation and enhanced healing time.

The location of the flap surgical sites will impact prevention. For example, immobilization and stabilization devices are unique to the abdomen, chest, extremities, and sacral region. Infection prevention measures for wounds are essential for nursing care. Incisions from flap procedures also have a higher chance of opening if the wound becomes infected (7). Prevention of hematomas is also meaningful, including the use of blood thinners. However, the safety precautions for blood thinners are different for each client.

Management and Treatment

It is estimated that 80% of free flaps can be salvaged if dehiscence or compromise is recognized early enough (11). As we mentioned, it is more common for flaps that are removed from (or applied to) the abdomen to open. The following terms describe the depth:

- Superficial dehiscence: the skin wound alone opens, but the rectus sheath remains intact.

- Full thickness dehiscence: the rectus sheath fails to heal and “bursts,” with protrusion of abdominal content.

- This occurs secondarily due to intra-abdominal pressure (for example, ileus) or poor surgical technique.

Once a cause is identified, the provider will determine the treatments for flap compromise. Treatment may include returning to the operating room for additional surgical intervention or simply evacuation of the hematoma through suctioning.

Recovery

The focus of recovery is the healing and thriving of the flap site and surgical wounds. The time of flap healing varies, and some may heal much quicker than others. There are four phases of wound healing to recognize: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and maturation (7).

- Hemostasis. This phase begins immediately after surgery when platelets release growth factors that alert various cells to start the repair process.

- Inflammatory. This process involves vasodilation so white blood cells in the bloodstream can move into the wound to begin cleaning the wound bed. Signs include edema and erythema.

- Proliferative. This phase generally begins a few days after the injury and includes capillary repair and growth, granulation tissue formation, collagen formation, and wound contraction (7).

- Maturation. During this phase, collagen strengthens the wound and fills in the wound gaps.

The healing process can be enhanced in many ways, including nutrition therapy, topical agents, compression therapy, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT). The recovery process for flap surgery will include management of pain and discomfort, disturbance of body image, impaired skin integrity, swelling, bruising, and gastrointestinal upset.

Outcomes for recovery should be measurable and achievable. Each patient will have unique recovery goals, integrating comorbidities and psychosocial aspects.

Examples of Patient Outcomes following flap surgery: (3)

- Patient safety: The Patient will attain safety by maintaining the intra- and extracellular environment.

- Healing of wounds: Wounds should heal properly, and complications will be prevented or managed

- Management of pain

- Prevention of further damage or skin breakdown

Ask yourself...

- How would you describe the process of healing?

- Can you name some underlying causes of flap dehiscence?

- What are some strategies to prevent infection of the surgical site?

Conclusion

As discussed throughout this course on flap surgery, nurses are key team members in the care and survival of flaps. Hopefully, you now understand what flap surgery is, its indications, and the types of flap surgeries. Critical knowledge includes pertinent assessment, drain or NPWT management, patient teaching, and prevention and management of possible complications.

Ask yourself...

- Can you name the various ways to classify flaps?

- Why do you think it’s important to classify flaps according to their blood supply?

- What do you think the reason is for flap surgeries following mastectomies and breast reconstruction?

- Can you name various indications for flap surgery following a burn?

- What are the comorbidities that may impact wound healing?

- Can you name common risks of surgeries?

- Can you think of reasons why elderly patients may have poor outcomes following flap surgery?

- Can you identify modifiable and non-modifiable pre-operative considerations?

- What do you think are some common fears and uncertainties among patients prior to flap surgery?

- Can you name teaching topics for a patient who is scheduled for a flap surgery?

References + Disclaimer

- Agarwal, P., Kukrele, R., & Sharma, D. (2019). Vacuum assisted closure (VAC)/ negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) for difficult wounds: A review. Journal of clinical orthopaedics and trauma, 10(5), 845–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcot.2019.06.015

- Chen, C. Y., Kuo, S. M., Tarng, Y. W., & Lin, K. C. (2021). Immediate application of negative pressure wound therapy following lower extremity flap reconstruction in sixteen patients. Scientific reports, 11(1), 21158. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00369-5

- Doenges, M.E., Moorhouse, M.F., & Alice C. Murr, A.C. (2019). Nursing care plans: guidelines for individualizing client care across the life span: Vol. 10th edition. F.A. Davis.

- Gold, C., Kournoutas, I., Seaman, S. C., & Greenlee, J. (2021). Bone flap management strategies for postcraniotomy surgical site infection. Surgical neurology international, 12, 341. https://doi.org/10.25259/SNI_276_2021

- Hong, J.P., Kwon, J.G. (2022). Flaps in Plastic Surgery. In: Maruccia, M., Giudice, G. (eds) Textbook of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82335-1_9

- Mazine, A., Hofer, S.O.P., & Yau, T.M. (2021). Infection, sternal debridement and muscle flap. In: Cheng, D.C., Martin, J., David, T. (eds) Evidence-Based Practice in Perioperative Cardiac Anesthesia and Surgery. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47887-2_57

- McNichol, Ratliff, C., & Yates, S. (2021). Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nurses Society core curriculum: wound management (Second edition.). Wolters Kluwer Health.

- Rohrer, Cook, J. L., & Kaufman, A. J. (Eds.). (2018). Flaps and grafts in dermatologic surgery (Second edition.). Elsevier.

- Saber AY, Hohman MH, Dreyer MA. (2022). Basic flap design. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563252/

- Strauch, B. (2016). Grabb’s encyclopedia of flaps. Volume II, Upper extremities, torso, pelvis, and lower extremities (4th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

- Vincent, A., Sawhney, R., & Ducic, Y. (2019). Perioperative care of free flap patients. Seminars in plastic surgery, 33(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1676824

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback!