Course

Frostbite Assessment and Treatment

Course Highlights

- In this course we will learn about assessing frostbite injuries, and why it is important for emergency and trauma nurses to understand.

- You’ll also learn the basics of the different stages, clinical signs and diagnosis

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of how to assess frostbite injuries

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 2

Course By:

Laura Kim

DNP, CPNP -AC/-PC, RN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

This course provides an overview of how frostbite is classified and the management approach depending on its severity. Emphasis is placed on the pathophysiology of frostbite, especially freeze-thaw-refreeze injury, because this can significantly impact the severity of the damage. Severe frostbite injuries are frequently managed in burn units; however, this course is developed to enable nurses in burn units to confidently care for frostbite injuries and nurses practicing across many specialties, including the emergency department and primary care.

Introduction

Frostbite is the most common type of freezing injury. Other types include immersion foot (formerly referred to as trench foot), hypothermia, and pernio (chilblains). Frostbite is defined as the freezing and crystallization of fluid in the interstitial and cellular spaces due to prolonged exposure to freezing temperatures.

The most commonly affected areas are the hands, feet, ears, nose, and lips. However, any exposed skin is susceptible to frostbite. Treatment aims to salvage as much tissue as possible to retain maximal function (1, 2). This course will focus on the pathophysiology of frostbite – namely, the dangers of freeze-thaw-refreeze injuries, the management of frostbite injuries, and an emphasis on preventing frostbite injuries.

Definitions

Cutaneous: having to do with the skin (3)

Sequelae: long-term complications from previous diseases, injuries, or trauma (4)

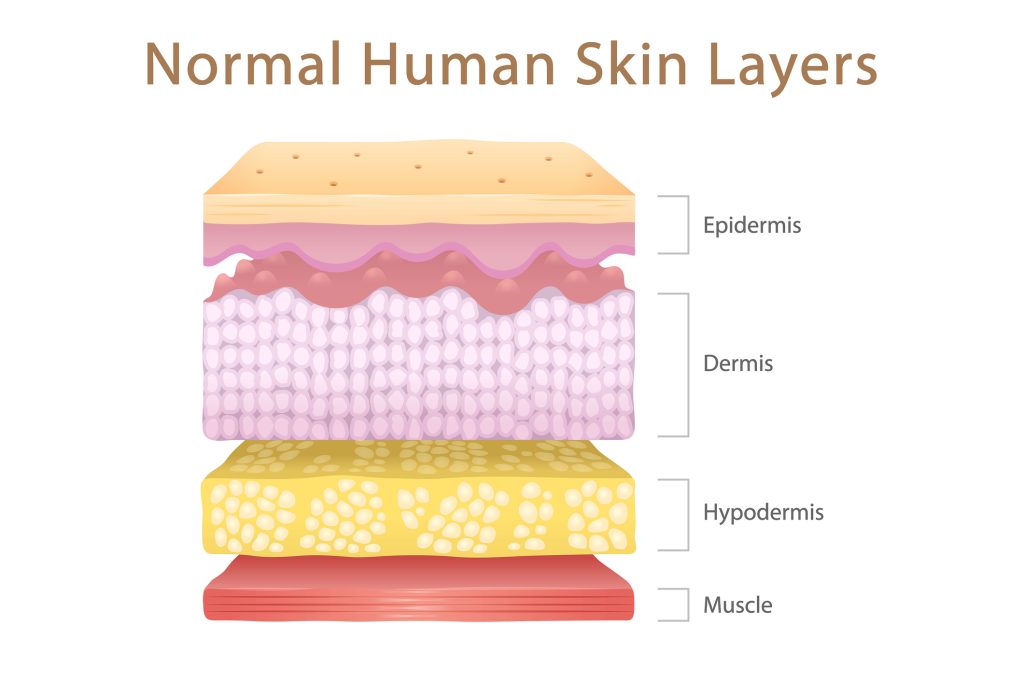

Skin Anatomy

Understanding the anatomy and purposes of the skin is essential for any healthcare provider caring for clients with integumentary disruption and dysfunction. The skin is a protective barrier that prevents internal tissues from exposure to trauma, ultraviolet (UV) radiation, temperature extremes, toxins, and bacteria. Additional functions include sensory perception, immunologic surveillance, thermoregulation, and managing insensible fluid loss (5). Cells residing in the three dermal layers carry out these crucial functions.

The outermost layer is the epidermis, which contains no blood vessels and is composed of different strata, which are layers of tissue arranged on top of each other (5). Epidermal cells reside within the different stratum, each serving an important function. The cells include keratinocytes, melanocytes, Langerhans cells, and Merkel cells.

Keratinocytes produce keratin and lipids necessary to create the epidermal water barrier. Melanocytes make melanin, the primary component of skin pigmentation. Langerhans cells are the skin’s first line of cellular immune defense essential for antigen presentation. Merkel cells are important in processing light touch stimuli (5, 6). The epidermis is between 0.2 millimeters (mm) to 1.6 mm thick (7).

The dermis supports the epidermis by providing nutrients. It gives the skin mechanical strength and elasticity thanks to a structural matrix composed of collagen, elastic fibers, and a substance containing glycosaminoglycans, proteoglycans, and glycoproteins. This matrix aids in hydration, movement of nutrients, and mechanical support (5, 8). The dermis comprises two layers: the superficial papillary dermis and the deeper reticular dermis. The superficial papillary dermis is thin, consists of loose connective tissue, is vascular, and contains mechanoreceptors. The reticular dermis is thicker and comprises dense connective tissue, larger blood vessels, mast cells, and nerve endings. Sweat glands, hair and hair follicles, muscles, sensory neurons, and blood vessels are all found within the dermis (5, 6). The dermis is between 1.5 mm to 4 mm thick (7).

The hypodermis sometimes called the subcutaneous fascia, is the deepest layer of skin between the dermis and underlying structures, such as muscles (8). The hypodermis comprises connective and adipose tissue and contains the structural units of adipose tissue, sensory neurons, and blood vessels. This layer plays a vital role in cushioning and insulation. The hypodermis is between 0.5 mm (in areas like eyelids) to 30 mm thick depending on the individual (amount of body fat) and the location of the body (5).

The dermal layers play a significant role in protecting and regulating the body. Serious frostbite injuries cause long-term sequelae and affect the client’s health and quality of life.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How does understanding the normal function and structure of the dermal layers impact your clinical care?

- Describe the function of each layer in your own words.

- What complications are possible depending on the depth of frostbite injury, considering the functions of each layer of skin?

Etiology

Frostbite occurs when skin is exposed to freezing conditions. The severity of injury depends on the absolute temperature and duration of cold exposure. The wind chill factor also affects the severity of frostbite. The actual temperature does not change due to the wind chill; however, it removes the warm air around the skin and increases its cooling rate (1, 2).

Several risk factors for frostbite can be categorized as extrinsic factors, systemic pathology, pharmacologic, and injury. Extrinsic factors include inadequate shelter/homelessness, inappropriate clothing, extreme cold exposure, high altitude, and smoking. Risk factors categorized as systemic pathology include Raynaud’s disease, diabetes, psychiatric illness, previous frostbite injury, peripheral vascular disease, and malnutrition.

These place the individual at risk because they may worsen tissue injury, and these conditions either impair internal organ insulation or contribute to dysfunctional vasculature (1, 9). Risk factors that are categorized as pharmacologic include beta-blockers, sedatives, anxiolytics, and illicit drugs. The fourth category is injury, including head injury, spinal cord injury, poly-trauma, and injuries that compromise circulation (2, 9).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How would the mechanism of action of medications such as beta-blockers, sedatives, and anxiolytics contribute to the risk of frostbite injury?

- How specifically do the extrinsic risk factors place an individual at risk for frostbite injury?

- How specifically do the risk factors for systemic pathology place an individual at risk for frostbite injury?

- Discuss why you disagree with classifying the risk factors for frostbite injury.

- What additional risk factors can you think of that can be added to each classification?

- What are the most commonly observed risk factors for serious frostbite injury in your local area and the community you serve?

Epidemiology

Limited data exist on the incidence of frostbite injuries, which are uncommon in the United States, except in northern states and Canada (2, 10). Historically, frostbite injuries were common in individuals inhabiting or exploring subfreezing environments and military service members (1, 11). More emphasis and training on frostbite prevention in military and wilderness exploratory endeavors (11).

There has been a shift to the majority of frostbite injuries occurring in urban areas, especially in individuals with social disadvantages (i.e., homelessness, poverty), psychiatric illness, and/or substance abuse. Studies on frostbite injuries in Canada and northern China both found alcoholism as a serious risk of frostbite. When alcohol is consumed, the peripheral blood vessels dilate, causing heat loss in the extremities.

Alcohol intoxication combined with AMS, especially losing consciousness, makes it impossible for an individual to seek help, further exacerbating heat loss (11). Outdoor sports participants are another group affected by frostbite injuries, accounting for a third of frostbite cases (12).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How can knowing the epidemiology of frostbite injury improve the healthcare team’s care?

- Discuss your local epidemiologic data for frostbite injuries.

- How can you use the epidemiologic data to develop resources for individuals at risk for frostbite injury?

Pathophysiology

Frostbite injury occurs in four overlapping phases: the pre-freeze phase, the freeze-thaw phase, the vascular stasis phase, and the late ischemic phase. The pathologic processes during these phases damage both the intracellular and extracellular spaces, causing tissue ischemia and necrosis (9).

Damage to the intracellular space results from increased oncotic pressure in the extracellular space from ice crystal formation within the tissues, leading to extracellular ice crystal formation. The change in the osmotic pressure gradient pulls water from the intracellular space into the extracellular space, causing intracellular dehydration. Intracellular homeostasis is further affected by protein and lipid disruption and electrolyte shifts. Additionally, when the temperature of the tissue continues to drop, ice crystals form in the intracellular space, causing the cell to swell and leading to structural damage to the cell due to the rupture of the cell membrane (9,12).

Cutaneous circulation is the blood flow within the skin, vital in maintaining thermal homeostasis. Normal cutaneous blood flow is 200 to 250 milliliters (mL) / minute. At 15 °C, the body attempts to conserve heat through immediate, localized vasoconstriction, and blood flow is approximately 20-50 mL/min. Vasoconstriction may be followed by temporary vasodilation as a physiologic reflex to maintain adequate blood flow to the extremities. This reflex is more frequently called the hunting reflex or hunting response. Increasing blood flow to the peripheral tissues results in a drop in the core body temperature, and the hunting response ceases.

Vasoconstriction resumes, limiting blood flow to the peripheral tissues (2, 9, 12). Vasoconstriction and tissue cooling cause edema from increased plasma viscosity, microvascular (endothelial) damage, and fluid shifts. Endothelial damage causes a pro-thrombotic state and microthrombi form. Microthrombi formation results in ischemia due to capillary occlusion (2, 9).

The most significant ischemia and necrosis are seen in freeze-thaw-refreeze injuries. Interstitial edema is caused by crystals in the tissue melting during rewarming. Tissue rewarming potentiates further microvascular clot occlusion due to mast cell degranulation, which releases histamine. Degranulation is when a cell releases its inner contents, specifically granules. Histamines increase vascular permeability and edema, causing local tissue ischemia (9). It is important to remember that tissue ischemia can occur during freezing and thawing processes.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Discuss why the hunting response is a beneficial or harmful physiologic reflex.

- What are the effects of a frostbite injury at the cellular level?

- Now that you know the pathology of frostbite injury, what specific medical interventions do you anticipate?

- How has your understanding of the pathophysiology of frostbite injury changed?

History and Physical Exam

To help predict the severity of the injury, which impacts subsequent management, the healthcare team must ask about the environmental temperature and duration of exposure for clients presenting with a frostbite injury. The team should also ask about comorbidities and medication usage that may impact circulation (1, 2, 9).

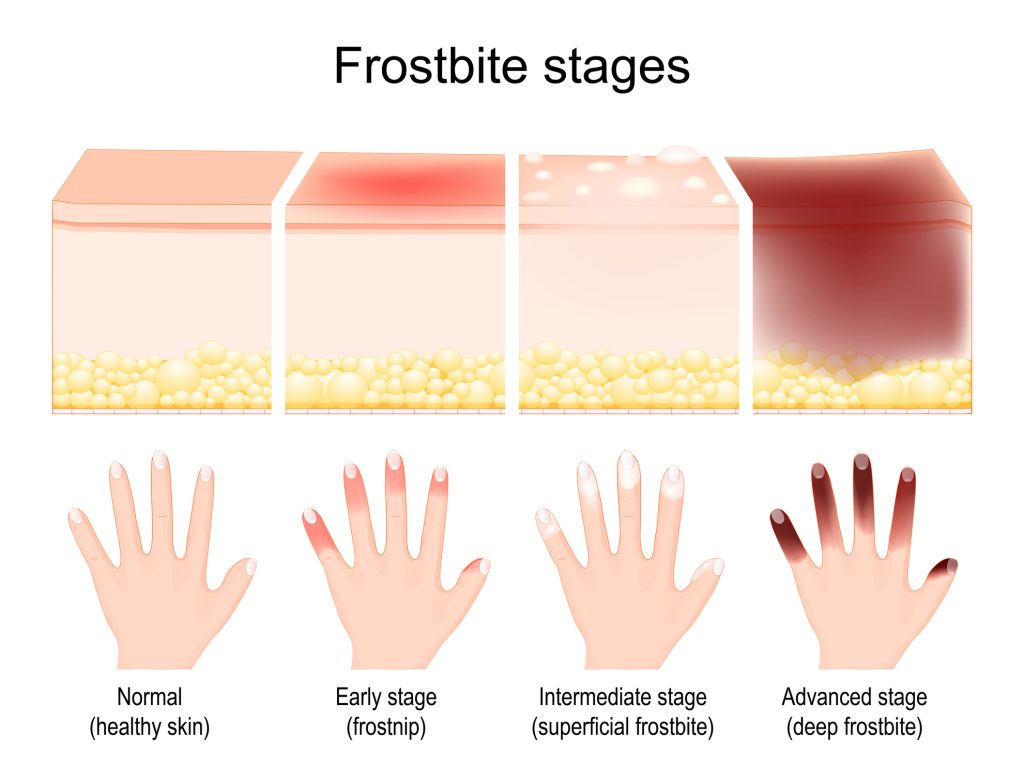

When completing the physical exam, remember that the affected tissue’s initial appearance does not accurately predict the extent of damage. This section will discuss the traditional four-degree staging system and the simplified superficial versus deep frostbite injury staging system. It is essential to consider that with either of the staging systems, there is still overlap between the levels because the injuries will not be uniform (11, 9).

The traditional staging is defined into four degrees. First-degree frostbite, sometimes referred to as frostnip, presents the following characteristics: epidermal involvement, non-sensate (numbness), dysesthesia (e.g., pain, burning, itching, or tingling), central pallor with surrounding erythema and edema, and desquamation (peeling skin). Second-degree frostbite has the following characteristics: full-thickness skin freezing without penetrating deeper tissues such as muscle and bone, clear blistering, erythema, and edema. Third-degree frostbite affects the subdermal plexus, a network of tiny blood vessels below the dermis.

The subdermal plexus provides blood supply to the skin. Third-degree frostbite also has the following characteristics: hemorrhagic blister formation, blue-gray skin discoloration, deep burning pain with rewarming (lasting up to five weeks), and thick gangrenous eschar formation within two weeks (1, 2). Fourth-degree frostbite affects muscle, bone, and tendons. It is characterized as frozen, stiff, avascular skin and tissue.

The skin is mottled with non-blanching cyanotic skin. The skin eventually becomes dry, black, and mummified. There is no pain upon rewarming and minimal post-thaw edema (2). A clear demarcation between viable and nonviable tissue appears within one month, and spontaneous amputation occurs approximately one month after demarcation (2). The four-degree staging system is deemed to have limited clinical usefulness because it has not demonstrated a correlation with survival or tissue loss (9).

Some healthcare institutions prefer the superficial versus deep frostbite injury staging system because it is found to have a better correlation between injury severity and outcome (2). The frostbite injury is classified as superficial if only the skin and subcutaneous (hypodermis) tissues are involved and the subcutaneous tissues are still soft. The affected tissue presents a white-mottled appearance that may become erythematous and edematous with rewarming. There is minimal capillary refill. Blisters are usually clear.

Any neurovascular dysfunction that is present is reversible. The client may experience a resolution of numbness with rewarming; however, the client may develop burning and stinging. Anticipated tissue loss is minimal to nonexistent. Deep injury involves the skin and subcutaneous tissue, extending to muscles, tendons, and bones. Upon rewarming, the affected tissue remains mottled and pulseless, and loss of sensation persists. Blisters are hemorrhagic, and there is increased loss of flexibility. Tissue loss is common, and there is a high risk of infection due to the loss of the skin barrier and the presence of devitalized tissue (2).

A third classification system, the Cauchy scheme, focuses on the anatomical level of cold-induced skin lesions and bone scanning. The Cauchy scheme assigns grades based on the anatomical level of cold-induced skin lesions and the results of bone scanning taken on day two after injury (11). Regardless of the staging method, different degrees of frostbite injury can occur within the affected body part.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is your experience with staging frostbite injuries?

- Which staging system have you or your institution determined to have more significant clinical utility and why?

Laboratory Studies and Imaging

Assessing the extent of tissue ischemia for severe frostbite injuries on clinical exam alone can be challenging. Radiologic studies can aid the healthcare team in identifying the extent of ischemia. Radiologic imaging offers little benefit in less severe cases of frostbite injury (2, 9).

Radiographs (X-rays) provide little information regarding the extent of frostbite injury. Soft-tissue edema may exist, but X-rays cannot distinguish between viable and nonviable tissue. X-rays help identify trauma-related fractures or dislocations or to identify complications such as osteomyelitis (2, 12).

Angiography is a preferred imaging modality for clients with severe frostbite injury. It uses contrast dye and X-ray imaging to evaluate the health of blood vessels. Some studies recommend angiography as the imaging method for frostbite (12). Angiography can aid in determining if a frostbitten extremity should be amputated based on the state of arterial filling and the number of arterial branches seen on angiography.

This imaging modality is also valuable for evaluating the effectiveness of thrombolytic therapy (2, 12). Angiography is limited to assessing the vascular system and cannot provide information on the metabolic status of the affected soft tissue. Renal insufficiency is a contraindication for angiography. It is important to remember that the contrast agent’s radiation dose is higher than that of bone scan imaging (12).

Bone scans using 99mTc-methylene diphosphonate given via intravenous injection can evaluate the perfusion status of frostbitten limbs and the tissue activity of the frostbitten area. In addition, bone scans can identify inflammation, ischemia, and wet gangrene. However, there is debate regarding the sensitivity and specificity of using bone scans to determine the need for limb amputation and delineate between necrotic and viable tissue (12).

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is another imaging modality for evaluating severe frostbite injury. MRA is useful because it can show the health of the blood vessels and surrounding tissue and accurately show the boundary of tissue necrosis (2, 12). MRA does not require ionizing radiation or a contrast agent, so it can be used in pregnant clients with contraindications to contrast agents. However, completing the testing is more costly and takes more time (2, 12).

Frostbite is a clinical diagnosis, and laboratory studies of tissue samples, blister fluid, or blood yield little helpful information except in cases with concurrent hypothermia or evaluating comorbidities (2). Laboratory studies can also be beneficial for identifying complications of frostbite injury, such as sepsis. The healthcare team may consider baseline laboratory studies, including a complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, glucose level, and liver function tests. Myoglobinuria can be detected on urinalysis. Gram stain and cultures if there is evidence of infection of frostbite wound (2). Coagulation studies must be closely monitored for clients requiring thrombolytics (i.e., heparin, atleplase).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How does your healthcare team determine which clients with frostbite injury require radiologic studies?

- Discuss the need for laboratory studies in clients with frostbite injuries.

- What additional laboratory studies would you anticipate for clients with previous underlying pathologies (i.e., diabetes mellitus)?

Management

Before addressing frostbite, healthcare providers, whether in the hospital setting or the field, should prioritize life-threatening conditions. This includes assessing airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs) and assessing for emergent conditions such as trauma, altered mental status, and hypothermia. If life-threatening conditions are not present or have been stabilized, the healthcare team can further evaluate the frostbite injury (9, 13).

The initial treatment of frostbite includes protecting the affected body part from further damage by removing constrictive clothing or jewelry, removing wet clothing, refraining from rubbing or massaging the damaged tissue, and beginning to rewarm the affected tissues. However, rewarming should only be started if there is no risk of refreezing. Freeze-thaw-refreeze injury causes more tissue damage than prolonged freezing (11, 13). Rewarming or hydrotherapy is a crucial step in preserving dermal circulation. Rapid rewarming is performed with a water bath between 37- 39 °C (98.6oF to 102.2oF) containing an antiseptic agent such as chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine. Antiseptic agents may reduce the amount of bacteria on the skin (10). Some guidelines recommend maintaining the temperature between 40- 41 °C (9, 10, 13). It is imperative to keep the temperature between the recommended ranges.

Because the tissue will likely be neuropathic, placing it in a water bath that is too hot places the client at risk for a scalding injury. Refreezing injury is risked if the water temperature exceeds the recommended range (9, 10, 13). Rapid rewarming should continue until the skin appears red or purple and/or is soft and pliable. This can take 15 minutes to one hour, depending on the depth of injury. Some guidelines recommend a minimum rewarming time of 30 minutes and as long as needed until the skin appears red or purple (9, 10, 13). The temperature should be monitored throughout warming with a thermometer. Reasonable options for water baths include commercial whirlpools, foot spa devices, or sous vide (9, 13). After the tissue is rewarmed, the healthcare team can grade the level of injury. Dry heat (i.e., hairdryer) should never be used to rewarm frozen tissues.

Frequently, clients undergoing rapid rewarming for frostbite experience severe pain. The healthcare team should provide judicious analgesia. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, namely ibuprofen, should be provided due to their selective antiprostaglandin activity and analgesic effects. Ibuprofen’s antiprostaglandin activity may help improve tissue perfusion (9). The healthcare team may need to include opioids or other pain management modalities, such as neuropathic pain medication and peripheral nerve blocks, to provide sufficient pain management (13).

In addition to rapid rewarming, other general management principles for frostbite injury include discussing smoking cessation in clients who are tobacco users because nicotine causes vasoconstriction. The client’s vaccine record should be reviewed to ensure tetanus vaccination is current (booster within five years). A tetanus vaccine should be administered if the vaccine status is unknown or a booster was given over five years ago (10, 13). The affected body part should remain elevated to minimize edema and venous stasis (2, 9).

Since the affected tissue is fragile, it should not be massaged, and measures should be taken to reduce friction and maceration (e.g., placing gauze between digits). Clients with frostbite affecting the lower limbs should be placed on strict, non-weight-bearing status. When healing the affected tissues, the clients should begin an active range of motion in the affected area under the guidance of physical therapy. The healthcare team should encourage a high-protein, high-carbohydrate diet to promote healing (2, 9).

Superficial (grade one or two) frostbite injuries can usually be discharged home if the pain is adequately controlled, the client can perform wound care and activities of daily living, and the client has adequate support systems / a safe discharge location and follows up with a primary care provider and wound care (13).

Clients with deep (grade three or four) frostbite injuries and clients with superficial frostbite injuries that do not meet the discharge criteria outlined in the previous paragraph require admission. The healthcare team should establish intravenous (IV) access and warm crystalloid fluids. Antibiotics should not be used as prophylaxis but should be administered in cases of cellulitis or sepsis, significant trauma, or other sources of infection (10, 13).

General management principles should still be followed for clients with deep frostbite injuries. If clients presenting with deep frostbite injuries meet the following criteria: it has been less than 24 hours since rewarming, they are not receiving active treatment for hypothermia, and there are no absolute contraindications to thrombolytics, thrombolytic therapy should be initiated as quickly as possible.

Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is the thrombolytic most frequently mentioned in the frostbite literature. tPA, also called alteplase, lyses the multiple intravascular thromboses that develop during the vascular stasis phase (9). Lysing the thromboses with tPA improves tissue survival by restoring perfusion to the affected tissue. Serial angiography (every 12 to 24 hours) is recommended to monitor tissue response to tPA (10).

Concurrent heparin administration is recommended to prevent thrombosis’s propagation (spreading). Depending on institutional policy, heparin may be continued for 48 to 72 hours after discontinuing tPA and sometimes longer in the form of low molecular weight heparin administered subcutaneously (2, 9, 10). Due to the high-risk side effects of thrombolytics, namely severe hemorrhage, tPA should only be administered after careful analysis of the risk versus benefits and in a facility where the client is closely monitored (2, 9, Alaska). Another concern with thrombolytic therapy is the risk of compartment syndrome following restoration of perfusion. Compartment syndrome occurs secondary to edema from the damaged capillaries (9).

Surgical sympathectomy was frequently used to improve circulation in frostbitten tissue. This is accomplished by disrupting a portion of the sympathetic nerve chain, which controls blood vessel constriction. This relaxes the blood vessels and improves blood flow to the damaged tissue (9). However, in many cases, Iloprost and other vasodilatory medications have replaced the need for surgical sympathectomy.

Iloprost, a synthetic prostacyclin analog, is a potent vasodilator in the small vessels of the pulmonary and systemic circulation. Iloprost also provides the therapeutic benefit of preventing platelet aggregation and, therefore, preventing microthrombi formation (9,11). A suggested infusion protocol for iloprost is 100 mcg iloprost in 500 mL 0.9% saline administered at a rate of 10 ml/hour intravenously for six hours daily for five days. Frequent monitoring is required every 30 minutes, so iloprost should be administered in a setting that allows for close client observation, precisely heart rate and blood pressure, due to its potent vasodilatory effects (9).

Additional supportive or supplemental interventions include buflomedil, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, subatmospheric pressure therapy, pentoxifylline, vitamin C, superoxide dismutase, and nifedipine. However, these modalities have limited testing in well-controlled human trials (2).

Blisters may form as a result of the freezing injury or after rewarming. Hemorrhagic blisters signify more profound tissue injury and should be left intact (10, 13). The healthcare team may elect to deroof small blisters with clear or cloudy fluid to prevent prostaglandins and thromboxane, which are sometimes found in blisters, from contacting the underlying tissue and causing damage (10). Some guidelines recommend the application of topical antibiotics, aloe vera, or an iodine-based topical to intact blisters. Aloe vera decreases prostaglandin and thromboxane production (10, 13).

There is a more conservative approach to surgical management of frostbite. Early surgical debridement is contraindicated in most cases. This is because the progression and reversibility are not accurately determined in the early stages of injury. Definitive demarcation of devitalized tissues occurs around six to eight weeks after injury (9). There are exceptions to conservative surgical management, including frostbite injuries with infection, gangrene, concurrent severe limb trauma, or compartment syndrome. These situations are uncommon and more likely to occur in clients with freeze-thaw-refreeze injuries (9,10).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are the absolute contraindications to thrombolytic therapy?

- How would you identify a client experiencing compartment syndrome?

- How does your knowledge of the freeze-thaw-refreeze injury impact your clinical decision-making for clients?

- Compare your unit’s guidelines and policies to the information provided in the management section.

- What areas in your clinical practice or unit’s policies need quality improvement or evidence-based questioning regarding managing frostbite injuries?

Prevention

Educating clients on frostbite prevention is essential. This is especially important for clients who have already experienced frostbite injuries because the affected tissue is more susceptible to frostbite injuries (2). The risk of frostbite injuries can be reduced by protecting skin from moisture, wine, and cold exposure, avoiding perspiration and wet extremities, increasing insulation by wearing several layers of loose clothing and wearing mittens instead of gloves, refraining from using alcohol, nicotine, and illicit drugs, use chemical hand and foot warmers, refrain from using emollients as a barrier (most lotions and creams increase the risk of frostbite) maintain adequate hydration and nutrition, and minimizing the length of time spent in cold weather. Suppose an individual must spend time in cold weather.

In that case, they should follow these recommendations, frequently (every 10 to 20 minutes) assess their extremities for numbness or pain, and recognize frostnip (grade one frostbite) early before it becomes more severe (2, 14). Prevention is crucial because frostbite injuries have significant complications, including tissue necrosis, gangrene, compartment syndrome, joint immobility, hyperhidrosis, anhidrosis, paresthesias, and sensory deficits (2).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- When is the best opportunity to discuss frostbite prevention with your clients?

- What prevention programs or resources does your community or medical institution have available?

Nursing Implications

Nurses have a comprehensive role in managing frostbite. Our role ranges from education on prevention and identifying frostbite as early as possible to working alongside specialists to provide the best outcomes for clients with severe frostbite. This includes monitoring clients receiving vasodilators and thrombolytics and any comorbid conditions. Nurses also ensure clients receive appropriate pain management, especially during rewarming.

There are cases where severe deformity or amputation occurs. The nurse can advocate for the client by acknowledging the grieving process and ensuring the client has access to the necessary resources (i.e., psychologists). Many specialists manage severe frostbite, including wound care, pain management, surgery (possibly vascular and plastic), physical therapy, occupational therapy, and interventional radiologists. The client may struggle to remember or understand all the information provided. Nurses should continue to advocate for their clients by ensuring they know the treatment plan, its risks versus benefits, and if other treatment options are available.

Conclusion

Frostbite is the most common type of frozen injury. However, it is a preventable injury through appropriate client education. Despite best efforts to prevent frostbite injury, it may still occur. It must be promptly recognized and managed. In circumstances where the affected cannot be thawed without risk of refreezing, it is best to refrain from attempting warm water baths to avoid further damage caused by freeze-thaw-refreeze injury.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What additional questions do you have about serious frostbite injuries?

- How will the continuing education module impact or change your care delivery to clients with frostbite injuries?

References + Disclaimer

- Basit H, Wallen TJ, Dudley C. Frostbite. [Updated 2023 June 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536914/

- Zonnoor, B. (2024, February 28). Frostbite. Medscape. Retrieved February 4, 2025, from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/926249-overview?icd=login_success_email_match_norm

- National Cancer Institute (n.d.). Definition of Cutaneous. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved February 15, 2025, from https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/cutaneous

- Hengsterman, R. E. (2023, October 23). Nurses’ Definition of Sequelae. Retrieved February 9, 2025, from https://nursingcecentral.com/definition-of-sequelae/

- Amirlak, B. (2025, January 22). Skin Anatomy. EMedicine Medscape. Retrieved February 9, 2025, from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1294744-overview#showall

- Yousef H, Alhajj M, Fakoya AO, et al. Anatomy, Skin (Integument), Epidermis. [Updated 2024 June 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470464/

- Chanda, A., Singh, G. (2023). Skin. In: Mechanical Properties of Human Tissues. Materials Horizons: From Nature to Nanomaterials. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-2225-3_2

- Kim JY, Dao H. Physiology, Integument. [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554386

- Hallam, M. J., Lo, S. J., & Imray, C. (2024). Skin Necrosis (pp. 99-107). L. Teot. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-60954-1_13

- Zaramo, T. Z., Green, J. K., & Janis, J. E. (2022). Practical Review of the Current Management of Frostbite Injuries. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open, 10(10), e4618. https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000004618

- Sheridan, R. L., Goverman, J. M., & Walker, T. G. (2022). Diagnosis and Treatment of Frostbite. The New England Journal of Medicine, 386(23), 2213-2220. https://doi.org/DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1800868

- Gao, Y., Wang, F., Zhou, W., & Pan, S. (2021). Research progress in the pathogenic mechanisms and imaging of severe frostbite. European Journal of Radiology, 137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2021.109605 F. Hengsterman, R. E. (2023, October 23).

- Alaska Trauma Systems Review Committee (2024, February 21). Alaska Acute Frostbite Management Guidelines. Health.Alaska.gov. Retrieved February 15, 2025, from https://health.alaska.gov/dph/Emergency/Documents/trauma/Alaska%20Acute%20Frostbite%20Management%20Guidlines.pdf

- McIntosh SE, Freer L, Grissom CK, et al. Wilderness Medical Society Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Frostbite: 2024 Update. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. 2024;35(2):183-197. doi:10.1177/10806032231222359

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate