Course

Flu Treatment, Symptoms, and Red Flags

Course Highlights

- In this course you will learn about flu treatment, symptoms, and red flags.

- You’ll also learn the basics of barriers, and the need for continuing education on this subject.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of flu prevention and precautions.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 2.5

Course By: Sarah Schulze MSN, APRN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

While COVID-19 has stolen the spotlight for highly contagious respiratory illnesses in the last several years, other potentially serious and easily spread viruses are still circulating and causing illness and hospitalizations across the world. Influenza is an example of one of those viruses.

Every year, between 5% and 20% of the US population fall ill with seasonal influenza. Complications such as pneumonia, exacerbation of chronic illness, and respiratory failure are possible and between 140,000 and 710,000 people are hospitalized with influenza each year.

Nurses must be able to recognize red flags and symptoms of serious illness related to seasonal influenza. Additionally, nurses must understand the importance of early treatment per CDC guidelines and the limitations of rapid influenza testing. In this course, we will discuss these topics and more!

Introduction

Every year, emergency waiting rooms, outpatient clinics, and inpatient hospital beds fill up with patients seeking treatment for the miserable symptoms brought on by the influenza virus. This illness does not discriminate and afflicts all ages, from young babies to the elderly, and everyone in between. Symptoms can range in severity from several days of fever, chills, and cough in bed at home, to weeks of hospitalization, respiratory distress requiring mechanical ventilation, and even complications resulting in death.

Starting in October and often lasting well into spring, flu season tasks healthcare workers everywhere with promoting prevention, quickly and efficiently identifying those infected, and appropriately managing symptoms and any secondary complications that may arise. In the last several years, the overloading of the healthcare system with COVID-19 infections has meant hospitals and clinics are even more hard-pressed to provide appropriate staffing, treatment, and medical resources to people affected by influenza.

An illness affecting the population on such a large scale requires healthcare professionals to stay up to date on disease trends, diagnosis and treatment protocols, and “red flags” of more serious cases, to minimize the impact of flu season and keep complications and mortality as low as possible.

This course will review disease trends in recent years, common and more insidious symptoms to help identify flu infections, available testing methods and their accuracy, pharmacologic treatments and the importance of their timing, supportive treatments and symptom management, and the “red flags” of dangerous secondary infections and complications.

Upon completion of the course, the reader should be comfortable participating in the prevention, identification, and management of the seasonal influenza virus.

Epidemiology

Influenza is a serious global issue that has been affecting humanity since the beginning of recorded history. Despite medical advances in recent years, flu remains a major public health concern in the United States, with millions of people being affected annually (4).

Between 140,000 and 710,000 people are hospitalized nationally each year, with around 51,000 deaths. Those most at risk are young children, those over age 65, and those with other chronic or underlying conditions such as asthma, diabetes, immunosuppression, etc. (4, 11)

Despite high rates of infection and risk of complications, the estimated annual vaccination rate amongst the general population remains at about half; 44.9% for adults and 55.4% for children for the 2022-2023 flu season (5). Both of these rates have been steadily declining in recent years, since the 2020 coronavirus pandemic. There is an increased rate of vaccination among healthcare workers (89.1% in 2023-2024), but as these are the people most likely to encounter and spread the virus, even that number could be improved (8).

Further complicating the situation, the influenza virus has several strains and possesses the ability to change its DNA (referred to as “drift and shift”) as it replicates, making it difficult to produce a highly accurate vaccine (7). Because of this, vaccines cannot be created far in advance if the most current strain is to be targeted. Vaccine shortages can result if new vaccines are not created at a fast enough rate throughout flu season (7).

There are antiviral medications available for the prevention and treatment of flu, however, this requires proper identification of those infected or most at risk for infection, and the administration of these medications is typically time-sensitive (10). Healthcare professionals should be familiar with common symptoms of the flu and be comfortable assessing patients, testing for, and diagnosing flu.

All these considerations for flu illustrate the intense need for educated, proactive healthcare workers to promote vaccines, quickly identify those most at risk or with active infections and treat effectively to keep the impact of flu minimalized.

The National Institute of Health has ongoing projects to keep available resources robust (14), but this research is only as strong as the healthcare professionals who implement it and are on the front lines of patient care. Staying up to date on current practices is paramount for national and global management of this resilient pathogen.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Do you think that the current rate of vaccinations among healthcare providers (89.1%) could be improved?

- Why do you think the rate of influenza vaccination has decreased in recent years since the COVID-19 pandemic?

- With up to 20% of the US population being affected annually, do you think enough resources are utilized in the prevention, recognition, and treatment of influenza?

- What could be done from a national, state, and local level to promote increased prevention, recognition, and treatment of influenza?

- When considering the population you work with, how accurate do you think public knowledge about influenza and influenza vaccines is?

Pathophysiology

Viruses are small pathogens containing genetic material that infect host cells and replicate within that host. They can exist for short periods of time outside of a host as an infectious virion and are spread between hosts through a variety of ways. Influenza is a specific group of RNA viruses that replicate within the epithelial cells of the respiratory tract (1).

There are three main types of flu viruses (A, B, and C). Viruses B and C typically only exist in humans, but A has been found in other mammals such as pigs and horses (1). There are also subtypes of each virus, depending on specific structure of the virus; these are labeled as H1-16 and N1-9 for hemagglutinin and neuraminidase, however, further discussion of these is beyond the scope of this course (1).

As the virus replicates within host cells, there can be subtle changes to the RNA over time, eventually adding up to more noticeable changes and resulting in these different subtypes. These slow changes are referred to as antigenic “drift” and are part of why creating a highly accurate flu vaccine is so difficult (1).

Typically, viruses that have drifted some are still susceptible to the current vaccine or there is some acquired immunity within the population. However, there is sometimes a more dramatic structural change referred to as antigenic “shift” that results in a completely new viral subtype and a population with virtually no immunity to this new agent (1). This can result in serious infection of pandemic proportions, such as the 2009 H1N1 outbreak (1).

Influenza viruses are typically spread through droplet transmission, when an infected person spreads microscopic drops of bodily fluids, typically through sneezing or coughing, which then encounters another susceptible person (1). These droplets usually only travel across air distances of 6 feet or less, however, they can be transferred further via indirect contact such as handshaking or by vectors (surfaces or objects where virions survive temporarily while waiting on contact with the next host) (1).

Once a host touches a contaminated vector and then touches their mucous membranes (nose, mouth, eyes, etc.), they can become infected. Other bodily fluids such as loose stools, vomit, and sputum can contain viral RNA and contribute to disease spread (1).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What factors contribute to the difficulty in creating an accurate flu vaccine each year, and how do antigenic drift and antigenic shift play a role in this challenge?

- How does the mode of transmission for influenza viruses affect public health strategies for prevention and containment of outbreaks?

- In what ways can indirect contact with contaminated surfaces contribute to the spread of influenza, and how might standard precautions help reduce this risk?

- How do the structural differences between subtypes of influenza viruses (e.g., H and N variations) influence the development of new viral strains and potential public health threats?

Prevention

Once pathogenicity is understood, providers are better able to prevent the spread of infection.

Flu Vaccines

The primary and most effective way to help prevent the spread of flu is through a high rate of vaccination in the general population. Current recommendations are for all individuals 6 months of age and older to receive a vaccine unless otherwise contraindicated (9).

It is critical for the most at-risk (children under age 2, adults older than 65, and those with comorbid conditions) and those working with high-risk individuals (healthcare and childcare workers) to receive vaccines.

For optimum protection, the goal for vaccine timing should be by the end of October, keeping in mind that full antibody production takes about two weeks after the vaccine is received. Though early vaccination is ideal, a flu vaccine can be administered at any point during flu season and patients requesting immunization later in the season should still be vaccinated (9).

The first-time children between 6 months and 8 years of age receive a flu vaccine, they will need 2 doses, 4 weeks apart (9). After receiving 2 doses, children only need 1 dose for all subsequent flu seasons (9).

There are some individuals who should not receive a flu vaccine, but this group is typically small. Among those who are contraindicated are infants under 6 months of age and anyone with a previous life-threatening reaction to a flu vaccine (9).

It was previously thought that anyone with an egg allergy should not receive the vaccine, since the viral components are grown in an egg medium, however, most recent recommendations suggest that this does not cause a reaction for most people and should be reviewed on an individual basis with one’s own primary care provider (9).

Anyone with a history of Guillain-Barré Syndrome should also consult their provider and may be advised to omit the vaccine. Patients with a current cough or cold accompanied by fever may be advised to postpone the vaccine until their symptoms have resolved (9).

Each year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study two factors of the current flu vaccine, efficacy and effectiveness. Randomized controlled trials are used to study the efficacy, or the intended result, of the vaccine in optimal conditions with healthy participants (9). Less formal observational studies are used to study effectiveness, or how well the vaccine is working in the “real world.”

As previously discussed, antigenic drift and shift mean that the annual vaccine is imperfect and does not always prevent illness as well as intended. For a general idea of the typical effectiveness, we can look at data from recent years: the vaccine was shown to be 36%, 30%, and 42% effective in 2021-22, 2022-23, and 2023-24 flu seasons, respectively (2).

Regardless of the lower levels of effectiveness compared to other vaccines, such as MMR, vaccination against flu can still prevent substantial numbers of illness and death when considering the population of the United States.

There are a few side effects to be aware of and to include in patient education with the administration of flu vaccines. The most reported side effect is local soreness around the injection site. This occurs in about 65% of patients vaccinated, does not typically interfere with activity, and resolves within a week (9).

Additional common side effects include:

- Fever

- Headache

- Muscle aches

- Nausea

- Fatigue

(9)

Rarely, an allergic reaction can occur, ranging from urticaria to anaphylaxis.

Children under age 2 are at a slightly increased risk of febrile seizures, particularly if a flu vaccine is given in combination with Prevnar and DTaP vaccines, therefore timing of routine vaccines in conjunction with a seasonal flu vaccine should be discussed with parents of young children (9.

Evidence suggests it is safe to give the influenza vaccine at the same time as the COVID-19 vaccine (9).

Though the actual correlation is unclear, there is also a suggested link between flu vaccines and the extremely rare condition of Guillain-Barre Syndrome (GBS). This often-life-threatening paralytic condition occurs in about 1-2 people per 100,000 each year, regardless of flu vaccine status.

Ongoing research indicates it is unlikely flu vaccines directly cause GBS and that other triggers such as recent viral illness are more likely to be the culprit, but the CDC estimates there may be a two per one-million chance of experiencing this complication after receiving a flu vaccine (6).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Why is it crucial for specific high-risk groups to receive the flu vaccine, and how does this contribute to overall public health?

- Given that flu vaccine effectiveness can vary by year, why is widespread vaccination still recommended despite lower levels of efficacy compared to other vaccines like MMR?

- What factors should healthcare providers consider when advising patients about flu vaccination timing, especially for children receiving the vaccine for the first time?

- How should healthcare providers approach patient concerns about flu vaccine side effects, including rare but serious complications like Guillain-Barre Syndrome?

- In light of the evidence regarding co-administration of flu and COVID-19 vaccines, what strategies might help improve vaccine uptake during flu season?

Standard Precautions

In addition to vaccines as the front line of disease prevention, there are multiple ways to help slow or prevent the spread of disease once flu season starts.

Hand hygiene and cough etiquette are amongst the most effective measures to prevent the spread of illness (3). These steps are easy and can be followed by anyone, regardless of if they are ill or not.

Avoid touching your mouth and nose. When coughing or sneezing, use a tissue to cover your nose and mouth, and then dispose of the tissue and wash your hands. Handwashing should be done with soap and water or alcohol-based hand sanitizer (3). In addition to standard precautions, anyone with respiratory symptoms and/or fever is encouraged to wear a surgical mask, a recommendation that was in place before more widespread masking with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hospitals and clinics can help stop the spread of infection by separating well patients from those with respiratory symptoms (9). People who are ill should not attend work or school and should limit their contact with good people as much as possible while symptoms are present (9).

Infected individuals are considered contagious 1-2 days before showing symptoms and up to a week after the illness begins; they should be fever-free for 24 hours before returning to work/school (9).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Why are hand hygiene and cough etiquette considered some of the most effective measures in preventing the spread of influenza?

- How does the contagious period of influenza influence recommendations for returning to work or school?

- How do you think the transmission of influenza might be impacted by the recent social changes following the COVID-19 pandemic?

- What sort of policies could be easily implemented in a public-school setting to reduce the spread of viruses and improve germ precautions?

Recognition of Flu

Despite prevention efforts, hundreds of thousands of people nationwide will contract the influenza virus each season.

When prevention efforts fail, the next major step is early identification. It is important for all healthcare workers to be familiar with the symptoms of flu and be able to quickly and accurately identify those with a probable diagnosis of flu.

Signs and Symptoms

Typical influenza infections start suddenly and include (11):

- Fever

- Headache

- Sore throat

- Cough

- Fatigue

- Nasal congestion or runny nose

- Body aches

- Chills

- Vomiting and diarrhea (more common in children)

Fever and acute symptoms usually begin 1-4 days after exposure to the flu and can last more than 7 days. Symptoms like fatigue and weakness can linger for longer, sometimes up to 2-3 weeks. While fever is typical of influenza infection, not all who are infected present with a fever (11). Clients infected with the flu are contagious about a day before and 7 days after symptoms begin. People with flu should avoid returning to work or school until they have been fever-free (without medications) for at least 24 hours (11).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What confusion, if any, do you note amongst your population of clients in regard to influenza “flu” symptoms and type of infection, compared to gastroenteritis “flu” and its symptoms?

- Why is early identification of influenza critical in controlling its spread?

- How does the variability in symptom presentation, such as the absence of fever in some cases, complicate the diagnosis of influenza?

- What strategies might help in ensuring accurate identification?

- Given that individuals can be contagious before showing symptoms, how can public health policies balance early detection with preventing transmission in community settings like schools and workplaces?

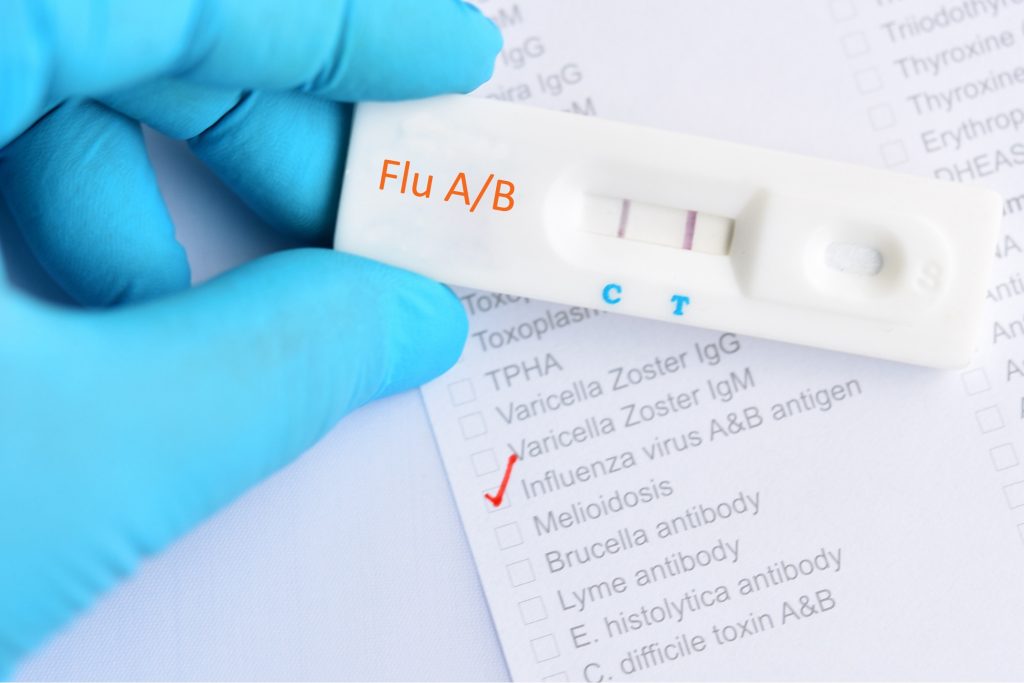

Testing for Influenza

It should be noted that patients with suspected flu can be treated purely based on clinical presentation and regional flu trends at that time; rapid flu tests do not have the highest sensitivity and therefore should not be the determining factor in regard to the necessity of treatment. However, there are several methods of testing for flu that can help confirm a suspected diagnosis of flu.

There are two main types of testing for flu, molecular assays and antigen detection tests. Molecular assays work by identifying viral nucleic acids or RNA in a respiratory specimen. They are sensitive and specific, meaning they can detect the virus at extremely low levels and the risk of false positive is very low (12)

There are rapid molecular assays that can result in as little as 15 minutes, identifying flu A or B, and there are also Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) and nucleic acid amplification tests available which take closer to 45 minutes to an hour for results and can identify specific subtypes of flu for a more in-depth diagnosis (12). Antigen detection tests are typically used in outpatient settings due to their cost effectiveness and rapid results (10-15 minutes) These rapid tests are up to anywhere from 50-70% sensitive and have specificity >90% (12).

While more accessible to the clinic setting, antigen detection tests are less accurate, and a negative result does not exclude a diagnosis of flu. In cases where flu is highly suspected and a rapid test result is negative, the result can be confirmed with a molecular assay or treatment can be started based on clinical presentation and a presumed false negative test result (12). Other illnesses such as COVID-19 may need to be ruled out or a simultaneous infection confirmed as well.

Where high-risk populations are concerned, such as asthma, heart disease, immune disorders, and other comorbid conditions, prompt treatment when flu is suspected may be recommended regardless of testing results (11,12).

Viral cultures are also available for the most in-depth results. While not practical for the clinical setting due to long result windows (3-10 days), viral cultures offer extremely detailed and useful information about the genetic details of current flu strains which is helpful when developing the next year’s vaccine (12).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Why might treatment for suspected influenza be initiated based on clinical presentation rather than waiting for test results, especially during peak flu season?

- How do the accuracy and limitations of antigen detection tests influence decision-making in outpatient settings when diagnosing and treating flu?

- Why are molecular assays preferred over antigen detection tests in certain cases, and how do their sensitivity and specificity impact flu diagnosis?

Treatment

Once flu has been identified clinically and laboratory confirmation is obtained (if desired), treatment of flu should be started as quickly as possible to maximize benefits of treatment and minimize potential complications of untreated illness.

There are several antiviral medications available by prescription in the United States:

- Oseltamivir

- Zanimivir

- Peramivir

- Baloxavir Marboxil

The first three medications work by blocking neuraminidase, an enzyme that allows newly replicated influenza viruses to be released from host cells. Baloxavir works by stopping the replication of the virus within the host cells. These medications shorten the duration and severity of symptoms (11).

Treatment should ideally be started within 48 hours of symptom onset, however there may still be benefits for severely ill patients or those who are young, elderly, suffering from comorbid conditions, or already hospitalized, and treatment initiation after 48 hours may be considered (11. Treatment should also never be delayed while awaiting laboratory results (11).

Treatment may be initiated based on clinical symptoms alone if symptoms are highly suggestive of influenza during an endemic period. The decision to treat is based on many factors, including the risk of complications and time since symptom onset.

Common side effects of these medications include:

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Headache

- Dizziness,

- Skin reaction (less common)

Typically, these medications are well tolerated, and prompt initiation of treatment should be encouraged, though influenza will typically resolve without antiviral treatment. (11).

In addition to antivirals, supportive care is a mainstay of treatment. Rest, hydration, cool mist humidifiers, antipyretics, and throat lozenges have all been shown to provide comfort and help with symptoms. Multiple studies have shown honey to be an effective cough suppressant and 1 tbsp in warm tea or water can work well to provide some relief (11).

Patients should be monitored for signs of dehydration, including dry mucous membranes and reduced urine output. Infection with influenza weakens the immune system and secondary infections may occur and require their treatment. Common complications include:

- Ear infections

- Sinusitis

- Pneumonia

(11)

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Why is it crucial to initiate antiviral treatment for influenza within 48 hours of symptom onset, and what factors might justify starting treatment beyond this window?

- How do neuraminidase inhibitors and baloxavir differ in their mechanisms of action, and why might this distinction be important when selecting a treatment for influenza?

- In addition to antiviral medications, what role does supportive care play in managing influenza symptoms, and how can it help prevent complications such as dehydration and secondary infections?

- How can the risks versus benefits of treatment with antivirals be discussed with clients eligible for antiviral treatment?

“Red Flags” – Potential Severe Complications and What Not to Miss

Most flu cases make a full recovery after 1-2 weeks of illness; however, some more serious complications can develop, including life-threatening symptoms and even death (13).

Flu can sometimes trigger systemic inflammation, leading to:

- Myocarditis

- Encephalitis

- Rhabdomyolysis

- Multi-organ failure

(13)

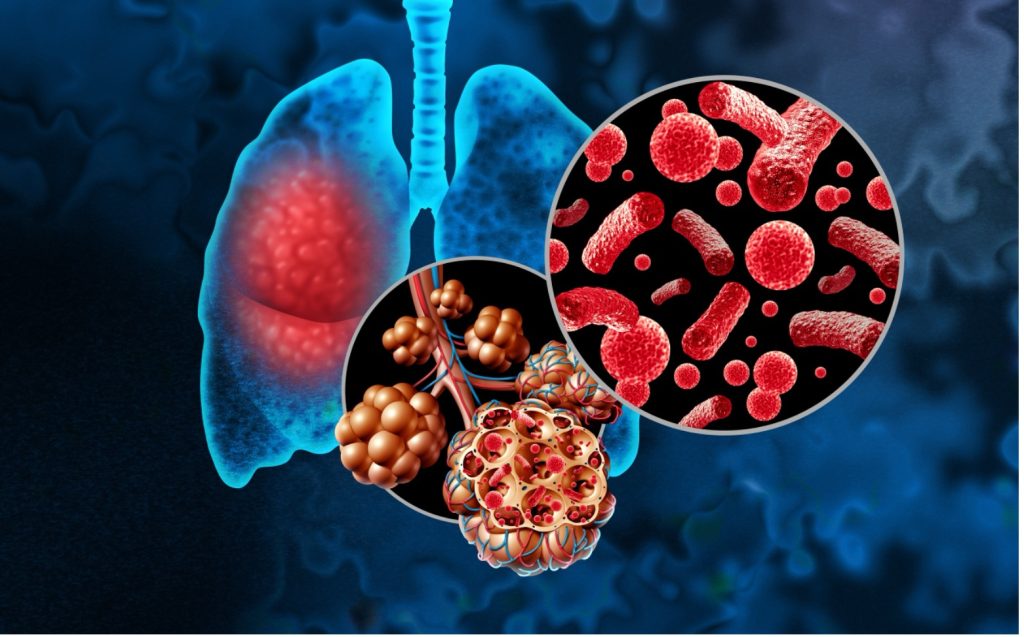

These conditions can be difficult to diagnose if suspicion is not high. Flu infections attack the usual defenses of the respiratory tract and predispose the body to secondary bacterial infections like pneumonia.

The body’s initial inflammatory response is beneficial to help the body fight off a flu infection but increasing inflammation or prolonged inflammation puts too much stress on the body and this extreme response can result in autoimmune disorders or sepsis (13). Those with asthma, heart disease, or other chronic conditions are at an increased risk of complications, as are young children and the elderly (13).

Post-influenza pneumonia is a well-described phenomenon, and the most common causative pathogen is Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA). This secondary infection should be considered in patients with respiratory symptoms and/or sepsis after a recent resolution of flu followed by returning or new/acute symptoms. It is important to consider MRSA as a causative agent when prescribing antibiotics to patients with post-influenza pneumonia (13).

“Red Flags” or warning signs that the body is working too hard to deal with the flu virus or is not compensating well include:

- Tachypnea or shortness of breath

- Cyanosis

- Tachycardia

- Hypotension

- Chest pain

- Dizziness and confusion

- Decreased urine output (>8 hours)

- Severe muscle pain

- Seizures

(13)

In children, fever >104 (or any fever in children <12 weeks of age) and retracting are concerning signs.

Any other signs/symptoms that are concerning or seem to be worsening warrant further workup and hospitalization to prevent further decline (13). Respiratory support with mechanical ventilation is needed in severe cases.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How would demonstration of “red flags” change a client’s management and what type of treatment/monitoring would they need?

- How does systemic inflammation during a severe flu infection contribute to serious complications like myocarditis and multi-organ failure?

- Why is it important for healthcare providers to be aware of secondary bacterial infections like post-influenza pneumonia?

- Why is it important to counsel clients about red flags even though they may not experience them?

Case Study 1

This case study involves a real patient’s experience with seasonal flu. Names, genders, ages, and some details have been changed to protect patient information.

Scenario

Jennifer is a 35-year-old female who presents to an urgent care clinic in mid-February with 2 days of rhinorrhea, cough, sore throat, body aches, and tactile fever. She has not received a flu vaccine this season. Recent medical history is significant for COVID-19 infection six weeks ago.

Assessment

Following triage, her vitals are recorded as: HR: 110, RR: 22, Temporal temperature: 101.3, SPO2: 97%, BP: 110/76.

She is visibly uncomfortable but sitting up on the exam table and can cooperate and carry on a conversation. She is breathing a little shallowly and has a frequent, coarse-sounding cough, but is overall not in any respiratory distress. She is congested and has clear rhinorrhea, her eyes are watery, and she has some posterior pharynx erythema, no cervical lymphadenopathy, and some faint rhonchi to her lungs that she can clear when coughing. Rapid strep and rapid flu swabs are collected, and the results are negative.

Plan

She is given a prescription for 5 days of 75mg BID TamifluⓇ (oseltamivir) which she fills and begins taking that afternoon. A viral culture is collected from her via nasopharyngeal swab for confirmation of suspected influenza.

Outcome Evaluation

Within 3-4 more days, Jennifer is fever-free and beginning to feel better despite some persistent fatigue. She works from home until her fever has resolved and her cough is improving. She makes a full recovery without sequelae. Three days later her viral culture indicates she has type B influenza, despite her negative rapid influenza test. This is a typical case of influenza, and the Tamiflu may have hastened her recovery and prevented severe illness. It also illustrates that rapid influenza testing has a low sensitivity and per CDC guidelines treatment may be based on clinical signs and symptoms.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Given Jennifer’s negative rapid flu test, why was antiviral treatment with Tamiflu prescribed based on her clinical presentation?

- How does Jennifer’s medical history of recent COVID-19 infection influence the way her healthcare providers approached her current symptoms and treatment plan for suspected influenza?

- What role do factors like Jennifer’s temperature, respiratory rate, and heart rate play in assessing the severity of her condition?

- Considering Jennifer’s recovery timeline, how might early antiviral treatment impact the course of influenza in otherwise healthy patients?

- Why is it important to consider the possibility of a false negative in rapid influenza testing, and how does this impact clinical decision-making in urgent care settings?

- How does the final diagnosis of type B influenza, confirmed through viral culture, emphasize the importance of follow-up testing and the limitations of using rapid tests for definitive diagnosis?

Case Study 2

This case study involves a real patient’s experience with seasonal flu. Names, genders, ages, and some details have been changed to protect patient information.

Scenario

Braxton is a 9-year-old male who presents to his PCP’s office with a sudden onset of high fever (103), headache, and cough that started that morning. It is December and he has not received a flu vaccine.

His vitals are stable. Exam reveals clear rhinorrhea, erythematous and enlarged tonsils, and frequent barky cough. Rapid strep and COVID-19 tests are negative, but a rapid flu test is positive for Influenza A.

He is given a prescription for Tamiflu (oseltamivir); however, his parents have some reservations about the medication due to an article they read on social media and decide not to give him the medicine.

They manage his symptoms with analgesics, Gatorade, and rest. About 11 days later he followed up in the office with complaints of persistent fatigue and new complaints of dizziness and difficulty breathing. Parents report a syncopal episode at home that morning, prompting today’s visit.

Assessment

His cough is still present, but better than it was, and he has been afebrile for about 5 days now. He looks very pale and complains of some dizziness as he gets up onto the exam table, his behavior is sluggish. He has some intercostal retractions and upon auscultation, there are crackles noted in his lungs bilaterally, particularly in the lower lobes. He has lost 4 lbs. since his previous visit. Vitals are somewhat concerning: HR: 145, RR: 27, Temporal temperature: 98.8, SPO2: 92%, BP: 90/54.

He seems poorly hydrated, and his overall appearance is concerning so you order some stat labs which indicate dehydration, an elevated WBC, and a chest x-ray which reveals bibasilar pneumonia.

Plan

He is admitted to the local children’s hospital for management of dehydration, respiratory support with supplemental oxygen, and antibiotic treatment of secondary pneumonia

Outcome Evaluation

After 4 days in the hospital, he is able to be weaned off of oxygen and is taking PO fluids well. He is discharged home where he makes a full recovery.

This case illustrates the importance of seasonal flu vaccines and early identification of influenza. When flu is neither prevented nor promptly treated, complications and secondary infections are likely to arise.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Given Braxton’s initial symptoms and the positive flu test result, how might early treatment with Tamiflu have potentially altered the outcome of his illness and prevented some of the complications he later experienced?

- Why is it important for healthcare providers to discuss the risks and benefits of flu antiviral treatment with parents, especially when concerns arise based on information from non-medical sources like social media?

- How does Braxton’s progression from initial flu symptoms to more severe complications highlight the importance of closely monitoring flu patients for secondary infections and complications?

- In the context of this case, what are the key indicators that suggest a flu infection has led to a more serious condition like pneumonia?

- How might Braxton’s lack of flu vaccination have contributed to the severity of his illness?

- What lessons can be learned from Braxton’s case regarding the importance of patient education for both parents and children, especially in terms of preventing influenza and recognizing when to seek medical care?

Conclusion

While influenza is an annual problem and can often seem routine or overshadowed by COVID-19, it is still of utmost importance that healthcare professionals stay vigilant in their knowledge of flu treatment and treat each case on an individual basis.

As the front lines for the promotion of flu prevention, early identification and treatment of flu, and maintaining alertness for potential complications, healthcare workers can have the biggest impact on the severity of the current flu season.

Staying up to date on current practices can help reduce the overall number of infections, rate of complications, and mortality.

References + Disclaimer

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2021). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. Hall E., Wodi A.P., Hamborsky J., et al., eds. 14th ed. Washington, D.C. Public Health Foundation, 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). CDC seasonal flu vaccine effectiveness studies. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/flu-vaccines-work/php/effectiveness-studies/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024b). Clinical safety: hand hygiene for healthcare workers. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/clean-hands/hcp/clinical-safety/index.html#:~:text=The%20bacteria%20can%20be%20transferred,most%20clinical%20situations15.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024c). Facts about estimated flu burden. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/flu-burden/php/about/faq.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024d). Flu vaccination coverage, united states 2023-24 influenza season. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/fluvaxview/coverage-by-season/2023-2024.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024e). Guillaine-Barre syndrome and flu vaccine. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccine-safety/guillainbarre.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2024f). How flu viruses can change: “drift” and “shift.” CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/php/viruses/change.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024g). Influenza and COVID-19 vaccination coverage among health care personnel – United States, 2023-24 influenza season. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/fluvaxview/coverage-by-season/health-care-personnel-coverage-2023-24.html#:~:text=Influenza%20vaccination%20coverage,-Overall%2C%2075.4%25%20of&text=While%20coverage%20among%20HCP%20working,65.2%25)%20(Figure%201).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024h). Seasonal flu basics. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccines/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024i). Treatment of influenza. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/treatment/index.html#:~:text=If%20you%20get%20sick%20with,after%20your%20flu%20symptoms%20begin.

- Cleveland Clinic. (2022). Flu (influenza). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4335-influenza-flu

- Cleveland Clinic. (2024b). Flu (influenza) test. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diagnostics/22716-flu-influenza-test

- Mayo Clinic. (2025). Influenza. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/flu/symptoms-causes/syc-20351719

- National Institute of Health. (2024). Influenza. NIH. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/influenza

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate