Course

Long COVID and other Updates

Course Highlights

- In this Long Covid and other Updates course, we will learn about the modes of transmission for SARS-CoV-2 and current epidemiological data.

- You’ll also learn to identify high-risk demographics for severe COVID-19 complications.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of the impact of Long COVID on healthcare systems and be aware of its disproportionate prevalence among different genders.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 1.5

Course By:

R.E. Hengsterman

MSN, RN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 virus, has led to significant global morbidity and mortality, pushing the healthcare system and research community into unprecedented challenges. Although the pandemic has waned in certain regions, Covid-19 is a multi-organ disease with a broad spectrum of manifestations and continues to pose a significant public health risk (28).

The emergence of Omicron and Delta variants and subvariants have complicated efforts to contain the virus’s proliferation (4). Beyond the immediate constellation of symptoms and acute manifestations, a cohort of individuals has emerged with a constellation of symptoms extending beyond their initial recovery (28).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How does the multi-organ nature of COVID-19, coupled with the emergence of new variants like Omicron and Delta, challenge traditional paradigms in healthcare delivery and public health strategies?

Brief Overview of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has been the greatest global health disaster of the century with a profound impact on the world, both in terms of public health and the global economy (1). Since identifying the RNA virus in Wuhan, China in December 2019, SARS-CoV-2 has spread to over 200 countries and territories, infecting over 750 million people, and killing over 7 million (2).

COVID-19 is a highly transmissible respiratory illness, often spreading between individuals in close contact (3). While vaccines have proven effective in mitigating the risk of severe illness and death, the threat remains considerable among vulnerable populations.

There are three primary modes of transmission for the SARS-CoV-2 virus, each requiring its own set of preventive measures. An individual can contract COVID-19 by inhaling air that carries droplets or aerosol particles containing the SARS-CoV-2 virus (3). This is more probable when near an infected individual or in confined spaces with poor ventilation where infected persons are present (3).

The virus can also spread when droplets containing the SARS-CoV-2 virus encounter an individual’s eyes, nose, or mouth. This can occur via coughing or sneezing by an infected person (3). Fomites are a method of transmission if an individual touches their eyes, nose, or mouth with hands that have encountered the SARS-CoV-2 virus (3).

The virus manifests through a range of symptoms after an incubation period between 2 and 14 days (3). Symptoms often appear 5-6 days post-exposure and can last between 1 to 14 days. These include fever, chills, and sore throat, while more severe manifestations can lead to respiratory distress and multi-organ failure (2).

Identifiable vulnerable demographics, such as those over 60 and individuals with pre-existing medical conditions including high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, immunosuppressed individuals and the unvaccinated are at an elevated risk for severe complications (2).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Given that COVID-19 has had such a profound impact on both public health and the global economy, how do you think healthcare systems and economic policies need to evolve to better prepare for future pandemics?

- While vaccines have proven effective in mitigating severe illness and death, they are not a complete solution for vulnerable populations. How should public health strategies balance between vaccination campaigns and other preventive measures to protect these groups?

- What are the implications for healthcare delivery models in serving populations that are at elevated risk for severe complications?

Current Incidence/Epidemiology

The epidemiology of COVID-19 has changed over the course of the pandemic. The epidemiology is complex and evolving. As with most RNA viruses, coronaviruses have a rapid evolution occurring on the timescale of months or years (7).

The original SARS-CoV-2 virus has evolved into several subvariants, some of which are more transmissible and/or evade immunity from previous infection or vaccination (7). This has led to several waves of infection, even in populations with high vaccination rates.

As of October 2023, the global incidence of COVID-19 is almost 6.3 cases per 100,000 people per day. This represents a significant decrease from the peak of the pandemic in early 2022, when the global incidence was over 100 cases per 100,000 people per day (5). Between September 25 and October 22, 2023, there was a significant decline in the global incidence of COVID-19, with new cases dropping by 42% compared to the preceding 28-day period. In this timeframe, over 500,000 new infections emerged (6).

The number of reported fatalities decreased by 43%, with more than 4,700 deaths. As of October 22, 2023, the global count stands at over 771 million confirmed cases and almost 7 million fatalities (6).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How does the rapid evolution of SARS-CoV-2, including the emergence of more transmissible variants that can evade immunity, challenge the current paradigms of epidemic control and vaccination strategies in populations with high vaccination rates?

- With the significant decrease in global incidence and fatalities, what are the ethical and strategic considerations for healthcare systems and policymakers in allocating resources between COVID-19 management and other pressing healthcare needs?

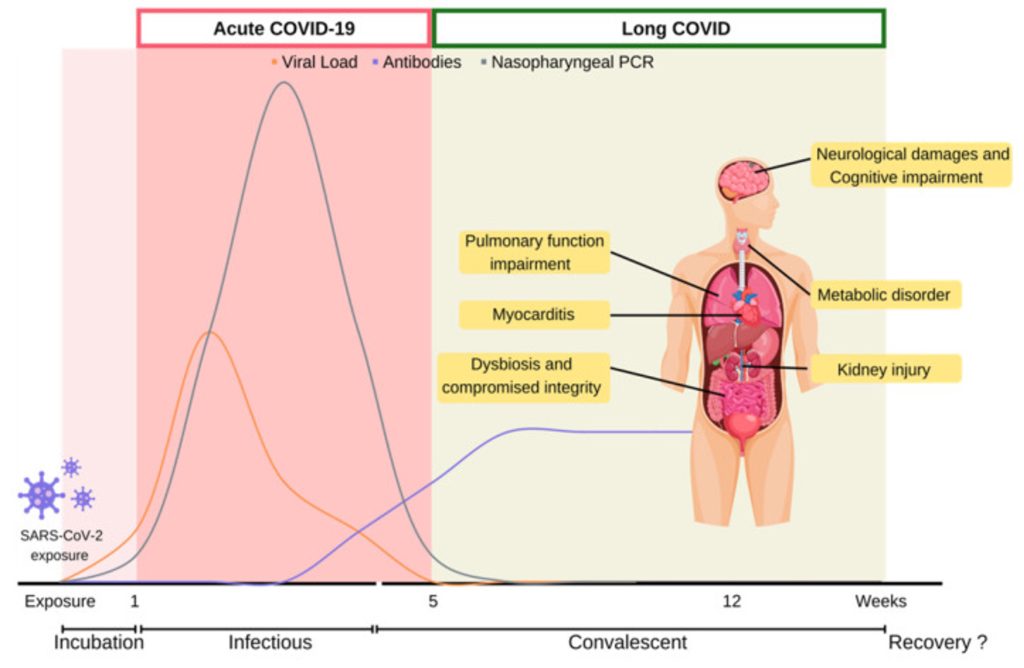

Long COVID

Another important epidemiological trend is the increasing prevalence of long COVID beyond the acute phase. Long COVID places a substantial strain on the healthcare system as a phenomenon that can occur after a COVID-19 infection, even if the initial infection was mild and (8, 9). Long COVID, also known as post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), has an incidence rate among non-hospitalized adults indicates between 7% to 40% of people infected with COVID-19.

Long Covid can last for months or even years (9, 10) The prevalence of long COVID is higher in women than in men (10). The data indicates a gender disparity: 8.5% of women had at some point contracted Long COVID, compared to 5.2% of men (10). Long COVID symptoms occurred in non-hospitalized or asymptomatic individuals (12).

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have laid out preliminary diagnostic criteria. The term “Long COVID” includes two distinct but related conditions: ongoing symptomatic COVID-19 lasting between 4 to 12 weeks, and post-COVID syndrome, which involves symptoms persisting for more than 12 weeks without an alternate diagnosis (11).

The term “post-COVID syndrome” serves as a broad categorization for a variety of unspecified conditions and physiological states. The National Institute of Clinical Excellence defines this syndrome by its multi-systemic and heterogeneous nature (12). Symptoms may be present in clusters and can vary over time (11). After 80 days of infection, less than 1% of COVID survivors achieved complete recovery at 80 days after infection (13).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Given that Long COVID can place a substantial strain on healthcare systems and has varying rates of incidence among different demographics, how should healthcare administrators and policymakers prioritize its management alongside the acute phase of COVID-19?

- Considering that Long COVID can manifest even if the initial infection was mild or asymptomatic, what are the implications for public health messaging and for encouraging behavioral modifications in populations that may perceive themselves as low risk?

- With the World Health Organization (WHO) and Centers for Disease Control (CDC) laying out preliminary diagnostic criteria for Long COVID and post-COVID syndrome, how should the healthcare system approach the standardization and evolution of diagnostic and treatment protocols given the multi-systemic and heterogeneous nature of the syndrome?

Symptoms

An infection via the SARS-CoV-2 virus leads to respiratory system dysfunction in long COVID. Symptoms of long COVID include a wide range of ongoing respiratory, neurologic, cardiovascular symptoms (8). The initial symptoms of long Covid in order of prevalence include fatigue, muscle pain, palpitations, cognitive impairment, dyspnea, anxiety, chest pain, and arthralgia (12). An international survey found fatigue, malaise, and cognitive impairment to be the most prevalent symptoms experienced among individuals with reported long COVID (14).

The SARS-CoV-2 virus targets the alveolar epithelium, inciting chronic inflammatory reactions that lead to ongoing production of inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (14). The cellular damage stimulates fibroblasts to lay down collagen and fibronectin, resulting in fibrotic alterations in lung tissue.

Over the long-term disruptions in coagulation pathways contribute to sustained inflammation and a hypercoagulable state, increasing the patient’s susceptibility to thrombosis (14).

Research indicates that 36% of individuals with long COVID experience some degree of shortness of breath, and 26% show signs of lung dysfunction (14). Respiratory abnormalities, including changes in total lung capacity and airway function, occur post-COVID-19 infection (14). Dyspnea, along with other respiratory issues such as chronic cough and diminished exercise capacity, are present among COVID-19 survivors (14).

A considerable number of long COVID patients develop cardiovascular issues. The high concentration of ACE2 receptors on cardiomyocytes offers a direct entry point for the SARS-CoV-2 virus (14). This can trigger chronic inflammation in the heart cells, leading to conditions such as myositis and cellular apoptosis (14). Persistent inflammation of the heart muscle and elevated levels of cardiac troponin occur in COVID-19 patients even two months post-diagnosis (14).

Data suggests a heightened risk of cardiovascular complications following a SARS-CoV-2 infection, including those not hospitalized (14). A prospective study revealed that 32% of COVID-19 survivors exhibited signs of cardiac damage three months after the initial infection (14). Furthermore, 89% of long COVID patients reported symptoms related to cardiac issues, with 53% experiencing chest pain, 68% noting palpitations, and 31% developing new-onset POTS (14).

Long COVID impacts the central nervous system via chronic neuro-inflammation activates glial cells, resulting in neurodegenerative conditions (14). The SARS-CoV-2 virus has the capacity to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and can exacerbate neuro-inflammation within the brain tissue (14). This pathological state of hyperinflammation and hypercoagulability could elevate the risk for thrombotic events (14).

Hyper-inflammation localized to the brainstem may contribute to autonomic dysregulation (14). CNS dysfunction is also a factor in long-term cognitive deficits with various studies suggesting that CNS-driven neuro-inflammation may underlie a range of neuropsychiatric abnormalities, such as chronic fatigue, sleep disorders, loss of taste and smell, post-traumatic stress disorder, cognitive impairments, and even instances of stroke (14). A

retrospective UK study involving 236,379 confirmed COVID-19 cases found that one-third of participants reported neuropsychiatric symptoms six months post-infection (14).

(14)

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How should medical professionals and healthcare systems adapt their diagnostic and treatment protocols to manage such a complex and multifaceted condition effectively?

- What are the implications for preventive measures and long-term care strategies, particularly for patients already at risk for thrombotic events?

- As research indicates a considerable number of Long COVID patients develop cardiovascular issues, how should this inform healthcare strategies for screening and early intervention among the non-hospitalized individuals with COVID-19?

- With evidence suggesting that Long COVID impacts the central nervous system and can contribute to neuropsychiatric abnormalities, what are the ethical and practical considerations for healthcare providers in diagnosing and treating these less tangible, but no less debilitating, symptoms?

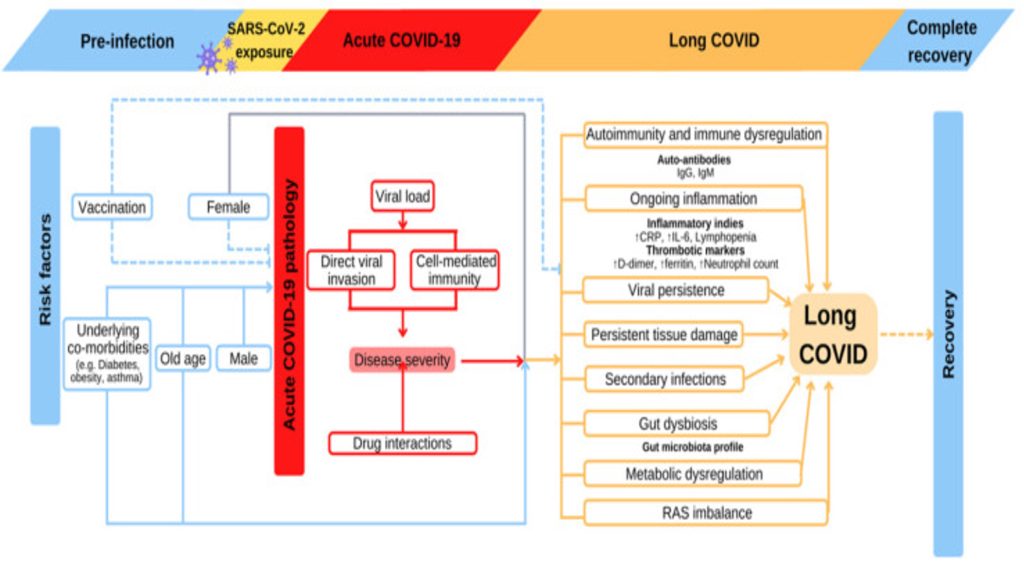

Risk Factors

The risk factors for developing long COVID are diverse and multifaceted, requiring consideration from both clinical and public health standpoints. Over the past three years, the ongoing evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has given rise to multiple variants, complicating public health strategies related to diagnosis, vaccination, and treatment (14). Each variant exhibits unique patterns of transmissibility and virulence, affecting both acute and long-term COVID-19 outcomes (14).

A correlation exists between pre-existing conditions and acute COVID-19 severity, as well as susceptibility to long COVID (14). Recent studies have identified several risk factors including age, gender, overall health status, asthma, and obesity (14). Asthmatic patients showed a higher likelihood of developing long COVID (14).

Type 2 diabetes and poor mental health also contribute to increased risk (14). Elderly individuals are at elevated risk for both acute and long COVID (14). The heightened risk in older individuals could be a secondary effect, influenced by the prevalence of pre-existing conditions and more severe acute reactions (14).

Epidemiological data highlight gender-based differences in long COVID incidence. Females under 50 are five times more likely to experience long-term symptoms with ovarian dysfunction as a potential contributor to long COVID among perimenopausal and menopausal women (14). Although males are more susceptible to acute infection, they report fewer cases of long COVID (14).

(14)

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Considering that pre-existing conditions such as asthma, type 2 diabetes, and poor mental health are risk factors for long COVID, how should public health agencies prioritize and strategize interventions to minimize long-term complications in these specific populations?

- Given the gender-based differences in long COVID incidence among females under 50, what are the implications for tailoring public health messages, treatment approaches, and research initiatives to account for these disparities?

Research

Research on long COVID is still in its initial stages, but there have been several significant advances in recent months. The key areas of current research on long COVID include identifying the risk factors for long COVID (8).

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) initiated the RECOVER (Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery) Initiative with the aim of elucidating the risk factors and etiology of Long COVID (8). In 2023, the RECOVER Initiative began multiple clinical trials to evaluate potential treatment avenues for Long COVID (8).

The RECOVER-VITAL trial aims to enroll up to 900 participants and to assess the effectiveness of an extended regimen of Paxlovid, an antiviral medication, in eliminating persistent SARS-CoV-2 infections (8).

The RECOVER-NEURO clinical trial focuses on cognitive rehabilitation methods to alleviate brain fog, memory lapses, and other cognitive challenges associated with Long COVID (8).

The RECOVER initiative includes various observational studies to explore the long-lasting health impacts of COVID-19 (8). RECON_19, conducted in Bethesda, Maryland, aims to understand the enduring medical issues faced by COVID-19 survivors (8). The Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Tissue Characterization in COVID-19 Survivors study will investigate the long-term cardiac implications of COVID-19 (8).

Pediatric studies include the PECOS (Pediatric COVID Outcomes Study) which will monitor the health outcomes of up to 5,000 children and young adults with COVID-19 over a three-year span (8). The Nationwide Pediatric Study for those under 25 is open to individuals who have COVID-19, Long COVID, or MIS-C, or those who may have exposure to the virus (8).

A study published in the journal Nature Reviews Microbiology in 2022 found that people with long COVID have several mitochondrial abnormalities, including reduced mitochondrial membrane potential and impaired mitochondrial metabolism (12). These abnormalities may be responsible for some of the most common long COVID symptoms, such as fatigue, exercise intolerance, and brain fog (12).

A study published in 2023 found that people with long COVID are more likely to have reactivation of the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a common herpesvirus that can cause mononucleosis. This finding suggests that EBV reactivation may play a role in the development of long COVID symptoms (15).

While there is still much to learn about long COVID, the pace of research is accelerating. Scientists are making considerable progress in understanding the underlying causes of long COVID and developing new treatments and interventions.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Given that the RECOVER Initiative is undertaking multiple clinical trials on the treatment of Long COVID, including antiviral medications and cognitive rehabilitation, what does this imply for future healthcare policies and resource allocation?

- Considering the findings that mitochondrial abnormalities are associated with long COVID symptoms such as fatigue and brain fog, how might this influence the direction of future research?

- The observation that Epstein-Barr virus reactivation may play a role in the development of long COVID symptoms is intriguing. What are the implications of this for the management and treatment of individuals with long COVID?

COVID-19 Vaccines and Boosters

The advancement of COVID-19 vaccines marks a milestone in medical research, curtailing the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and minimizing morbidity and mortality rates. The data proves COVID-19 vaccines are safe and reduce COVID-19 mortality (16).

The mRNA-Based Vaccines (Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna) utilize messenger RNA technology to instigate the cells to synthesize the virus’s spike protein to elicit an immune reaction (17). The viral vector-based vaccines (AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson) employ a benign adenovirus to ferry DNA for the spike protein (18). The AstraZeneca vaccine is a chimpanzee adenovirus vaccine vector made up of replication deficient chimpanzee adenoviral vector (18).

Protein subunit vaccines, such as Novavax, adopt fragments of the spike protein to induce an immune response (19). Subunit vaccines contain only the pathogens antigenic components required to elicit effective immune responses (19). The inactivated or live attenuated vaccines such as Sinopharm and Covaxin use a deactivated form of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, while Sputnik V incorporates two varying adenovirus vectors for its dual doses (20, 21).

Current research indicated that unvaccinated individuals faced the highest mortality risk from COVID-19, irrespective of their age or underlying health conditions (22). Although some breakthrough infections did lead to fatalities, vaccines continued to offer a substantial safeguard against mortality (22). For individuals below the age of 65, the vaccines demonstrated an 81.7% efficacy rate in preventing death (22).

The Pfizer vaccine led in terms of protective efficacy, with an 84.3% rate, followed by Moderna at 81.5% and Jansen at 73% (22). Among those aged 65 and older, the overall effectiveness of vaccines in averting death stood at 71.6% (22). Moderna showed the highest effectiveness at 75.5%, with Pfizer at 70.1%, and Jansen at 52.2% (22).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Given the varying rates of vaccine efficacy in preventing death among different age groups, how might this data inform public health strategies?

- The distinct types of COVID-19 vaccines—mRNA-based, viral vector-based, protein subunit, and inactivated or live attenuated—each have their distinct mechanisms of action. What does this diversity imply for the management of breakthrough infections and the potential need for booster shots?

2023 Recommendations

COVID-19 vaccines and booster shots are integral to the international strategy against the pandemic. Immunity against the SARS-CoV-2 virus starts to wane after the completion of the initial series of vaccine doses. To maintain optimal protection against COVID-19, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advises individuals aged 6 months and above to keep their vaccinations current, including receiving booster shots if they qualify (22).

COVID-19 vaccines and boosters are safe and effective at preventing serious illness, hospitalization, and death from COVID-19 (22). The CDC recommends that everyone aged 5 years and older get vaccinated and boosted with bivalent Covid vaccine (22). Individuals aged 50 years and older and people with immunocompromised conditions should get a second booster dose (23, 24).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are the ethical and logistical implications of advising a second booster dose for individuals aged 50 years and older and those with immunocompromised conditions?

- How might this guidance intersect with vaccine availability and distribution on a global scale?

Nursing Implications

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses serve in diverse capacities, spanning from clinical care and infection management to educational outreach and policy advocacy (25). The pandemic has underscored the fragmented nature of our healthcare systems and the absence of a cohesive strategy for addressing public health emergencies (25).

Nurses, with their specialized knowledge in infectious diseases, health disparities, social determinants of health, and innovative patient care models, offer invaluable insights for enhancing our approach to healthcare crises (25). Nurses are essential in assessing COVID-19 patients, monitoring vitals, and managing symptoms, monitoring, and overseeing patient isolation measures and educating patients on COVID-19 symptoms, prevention, and vaccination (26).

Given the ever-changing dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses must remain agile, informed, and prepared to adapt to new challenges. Their role is pivotal in both the clinical and administrative aspects of healthcare delivery, calling for a multifaceted approach to manage this ongoing global health crisis.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How might the healthcare system integrate the specialized knowledge that nurses possess in infectious diseases, health disparities, and social determinants of health into a cohesive strategy for future public health emergencies?

- Considering the agility and adaptability required of nurses in the COVID-19 pandemic, what specific training or support systems should nurses maintain to fulfill their multifaceted roles in both the clinical and administrative settings?

- What strategies could be employed to ensure that nurses can contribute in a multidisciplinary approach to the evolving challenges posed by long COVID, both in terms of patient care and health policy advocacy?

Conclusion

Long COVID underscores the evolving and complex nature of the COVID-19 pandemic. Long COVID, or Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection (PASC), represents a lingering and debilitating issue that challenges patients and the healthcare system at large (27). Its multi-systemic effects highlight the need for a multidisciplinary approach to treatment and research,

Nurses must maintain a flexible yet authoritative role in implementing these changes, from direct patient care to health policy advocacy.

References + Disclaimer

- Naseer, S., Khalid, S., Parveen, S., Abbass, K., Song, H., & Achim, M. V. (2023). COVID-19 outbreak: Impact on global economy. Frontiers in Public Health, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1009393

- World Health Organization: WHO & World Health Organization: WHO. (2023, August 9). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)

- Healthcare workers. (2023, October 27). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/non-us-settings/overview/index.html

- Katella, K. (2023, September 1). Omicron, Delta, Alpha, and More: What to Know About the Coronavirus Variants. Yale Medicine. https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/covid-19-variants-of-concern-omicron

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. (2023). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard with Vaccination Data. https://covid19.who.int/

- COVID-19 Epidemiological update – 27 October 2023. (2023, October 28). https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-epidemiological-update—27-october-2023

- Markov, P. V., Ghafari, M., Beer, M., Lythgoe, K. A., Simmonds, P., Stilianakis, N. I., & Katzourakis, A. (2023). The evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 21(6), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-023-00878-2

- Long COVID Information and Resources | National Institutes of Health. (2023, September 28). NIH COVID-19 Research. https://covid19.nih.gov/covid-19-topics/long-covid

- Ford, N. D., Slaughter, D., Edwards, D. L., Dalton, A. F., Perrine, C. G., Vahratian, A., & Saydah, S. (2023). Long COVID and significant activity limitation among adults, by age — United States, June 1–13, 2022, to June 7–19, 2023. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 72(32), 866–870. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7232a3

- Adjaye-Gbewonyo, D., Vahratian, A., Perrine, C. G., & Bertolli, J. (2023). Long COVID in Adults: United States, 2022. https://doi.org/10.15620/cdc:132417

- El-Rhermoul, F., Fedorowski, A., Eardley, P., Taraborrelli, P., Panagopoulos, D., Sutton, R., Lim, P. B., & Dani, M. (2023). Autoimmunity in long Covid and POTS. Oxford Open Immunology, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfimm/iqad002

- Davis, H., McCorkell, L., Vogel, J. M., & Topol, E. J. (2023). Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms, and recommendations. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 21(3), 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2

- Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, Wei H, Low RJ, Re’em Y, Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. eClinicalMedicine. 2021. 38

- Koc, H. C., Xiao, J., Liu, W., Li, Y., & Chen, G. (2022). Long COVID and its Management. International Journal of Biological Sciences, 18(12), 4768–4780. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.75056

- Bernal, K. S., & Whitehurst, C. B. (2023). Incidence of Epstein-Barr virus reactivation is elevated in COVID-19 patients. Virus Research, 334, 199157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2023.199157

- Wong, M. K., Brooks, D. J., Ikejezie, J., Gacic-Dobo, M., Dumolard, L., Nedelec, Y., Steulet, C., Kassamali, Z., Açma, A., Ajong, B. N., Adele, S., Allan, M., Cohen, H. A., Awofisayo-Okuyelu, A., Campbell, F., Cristea, V., De Barros, S., Edward, N. V., Waeber, A. R. E. C., . . . Van Kerkhove, M. D. (2023). COVID-19 Mortality and progress toward vaccinating older adults — World Health Organization, Worldwide, 2020–2022. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 72(5), 113–118. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7205a1

- Chavda, V. P., Soni, S., Vora, L. K., Soni, S., Khadela, A., & Ajabiya, J. (2022). MRNA-Based Vaccines and Therapeutics for COVID-19 and future pandemics. Vaccines, 10(12), 2150. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10122150

- Vanaparthy, R., Mohan, G., Vasireddy, D., & Atluri, P. (2021). Review of COVID-19 viral vector-based vaccines and COVID-19 variants. Le Infezioni in Medicina: Rivista Periodica Di Eziologia, Epidemiologia, Diagnostica, Clínica E Terapia Delle Patologie Infectiva, 29(3), 328–338. https://doi.org/10.53854/liim-2903-3

- Heidary, M., Kaviar, V. H., Shirani, M., Ghanavati, R., Motahar, M., Sholeh, M., Ghahramanpour, H., & Khoshnood, S. (2022). A comprehensive review of the protein subunit vaccines against COVID-19. Frontiers in Microbiology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.927306

- Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy (OIDP). (2022, December 22). Vaccine types. HHS.gov. https://www.hhs.gov/immunization/basics/types/index.html

- Joshi, G., Borah, P., Thakur, S., Sharma, P., Mayank, & Ramarao, P. (2021). Exploring the COVID-19 vaccine candidates against SARS-CoV-2 and its variants: where do we stand and where do we go? Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutic, 17(12), 4714–4740. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.1995283

- Breakthrough Infection study compares decline in vaccine effectiveness and consequences for mortality – Public Health Institute. (2022, January 6). Public Health Institute. https://www.phi.org/press/breakthrough-infection-study-compares-decline-in-vaccine-effectiveness-and-consequences-for-mortality/

- National Institutes of Health | COVID-19 vaccine studies and clinical trials. (2023, September 28.). NIH COVID-19 Research. https://covid19.nih.gov/covid-19-vaccines

- Coronavirus Disease 2019. (2022). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2022/s0328-covid-19-boosters.html

- COVID-19 and the nursing profession: Where must we go from here? (2022). Margolis Center for Health Policy. https://healthpolicy.duke.edu/covid-19-and-nursing-profession-where-must-we-go-here

- Fawaz, M., Anshasi, H., & Samaha, A. (2020). Nurses at the front line of COVID-19: Roles, responsibilities, risks, and rights. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 103(4), 1341–1342. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0650

- Proal, A. D., & VanElzakker, M. B. (2021). Long COVID or post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC): an overview of biological factors that may contribute to persistent symptoms. Frontiers in Microbiology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.698169

- Nalbandian, A., Sehgal, K., Gupta, A., Madhavan, M. V., McGroder, C., Stevens, J. S., Cook, J. R., Nordvig, A. S., Shalev, D., Sehrawat, T. S., Ahluwalia, N., Bikdeli, B., Dietz, D., Nigoghossian, C. D., Liyanage-Don, N., Rosner, G., Bernstein, E. J., Mohan, S., Beckley, A., . . . Wan, E. (2021). Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nature Medicine, 27(4), 601–615. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate