Course

Louisiana APRN Bundle

Course Highlights

- In this Louisiana APRN Bundle, we will learn about common side effects, including severe possible side effects, of medications used to manage asthma.

- You’ll also learn the clinical criteria for prescribing SSRIs.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of factors when prescribing opioids, indications, and effects.

About

Pharmacology Contact Hours Awarded: 12

Course By:

Various Authors

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Asthma Treatment and Monitoring

Introduction

When hearing the phrase asthma, what comes to mind? If you’re an advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) with prescriptive authority, you’ve definitely heard of asthma before. Even as a nurse or maybe before nursing school, conversations about prescription drug use and respiratory health existed every so often.

Presently, patients seek guidance and information on various health topics from APRNs, including medication management and respiratory health. The information in this course will serve as a valuable resource for APRNs with prescriptive authority of all specialties, education levels, and backgrounds, to learn more about medications that can treat and manage asthma.

Defining Asthma

What Is Asthma?

Asthma is a non-communicable chronic health condition that affects the airways of the lungs and affects millions of people nationwide. Asthma is often diagnosed in childhood and can resolve in adulthood or continue for the rest of a patient’s life. Several studies postulate the cause of asthma, but there is no definitive cause.

Genetics, age, environmental exposures, smoking, and a history of allergies are thought to play a role in asthma severity and development. Clinical presentation of asthma often includes trouble breathing, chronic airway inflammation, and airway hyperresponsiveness. Assessment for asthma often includes patient history, clinical presentation, spirometry testing, and pulmonary function tests (PFTs).

What Are the Stages of Asthma?

Since asthma is a chronic condition, several established guidelines can be used to determine the severity of asthma and explore possible medication options. Depending on the stage of asthma and patient response to existing therapy, treatment and management vary.

The four stages of asthma include intermittent, mild, moderate, and severe. Based on the 2020 National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) guidelines, here is the standard criteria for what constitutes each stage of asthma (2).

Intermittent asthma is characterized with the following clinical presentation and assessment (2):

- Patient history of respiratory symptoms, such as cough, trouble breathing, wheezing, or chest tightness <2 times a week

- Asthmatic flare-ups are short-lived with varying intensity

- Symptoms at night are <2 a month

- No asthmatic symptoms between flare-ups

- Lung function test FEV 1 at >80% above normal values

- Peak flow has <20% variability am-to-am or am-to-pm, day-to-day

Mild persistent asthma is characterized with the following clinical presentation and assessment (2):

- Patient history of respiratory symptoms, such as cough, trouble breathing, wheezing, or chest tightness 3-6 times a week

- Asthmatic flare-ups may affect activity level and can vary in intensity

- Symptoms at night are 3-4 times a month

- Lung function test FEV1 is >80% above normal values

- Peak flow has less than 20-30% variability

Moderate persistent asthma is characterized with the following clinical presentation and assessment (2):

- Patient history of respiratory symptoms, such as cough, trouble breathing, wheezing, or chest tightness daily

- Asthmatic flare-ups may affect activity level and can vary in intensity

- Symptoms at night are >5 times a month

- Lung function test FEV1 is 60%-80% of normal values

- Peak flow has more than 30% variability

Severe persistent asthma is characterized with the following clinical presentation and assessment (2):

- Patient history of respiratory symptoms, such as cough, trouble breathing, wheezing, or chest tightness continuously

- Asthmatic flare-ups affect activity level and often vary in intensity

- Asthmatic symptoms at night are constant

- Lung function test FEV1 is <60% of normal values

- Peak flow has more than 30% variability

Based on patient history, clinical presentation, and these criteria, treatment can be administered to decrease the symptoms of the patient. If a patient presents with symptoms that are outside of your scope of work or understanding, you can always refer patients to a pulmonologist or asthma specialist.

Often times, more severe cases of asthma and asthma emergencies require increased frequency and dosing of asthma-related medications. Health care provider professional discretion and patient condition should guide therapy. Consider reviewing a patient’s medication history, pulmonary function, and health history prior to prescribing asthma medications (1).

What Are Asthmatic Emergencies?

Asthmatic emergencies are if a patient has asthma symptoms that are beyond what they typically experience and are unable to function without immediate medical intervention. Asthma emergencies can occur as a result of a patient being unable to access their asthmatic medications, being exposed to a possible allergen, or being under increased stress on the body.

Asthmatic emergencies often require collaborative medical intervention, increased dosages of medications discussed below, and patient education to prevent future asthmatic emergencies (1).

What If Asthma Is Left Untreated?

Depending on the clinical presentation and severity of asthma, asthma can cause several long-term complications if left untreated. If asthma is not properly managed, several complications, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), decreased lung function, permanent changes to the lungs’ airways, and death can occur (1, 2).

Defining Asthma Medications

What Are Commonly Used Medications to Manage Asthma?

Commonly used medications to manage asthma include inhaled corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids, short-acting beta agonists (SABAs), long-acting beta agonists (LABAs), long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LABAs), adenosine receptor antagonists, leukotriene modifiers, mast cell stabilizers, and monoclonal antibodies. The dosage, frequency, amount of asthma management medications, and medication administration route can all vary depending on clinical presentation, patient health history, and more.

How and Where are Asthma Medications Used?

Asthma medications can be used routinely or as needed for management of asthma symptoms depending on the patient. Asthma medications can be used at home, in public, and in health care facilities. Depending on the specific asthma medication and dosage, these medications can be taken by mouth, by an external device, such as an inhaler, via subcutaneous injection, or via intravenous solution (1).

What Are the Clinical Criteria for Prescribing Asthma Medication?

Clinical criteria for prescribing asthma medication can depend on the clinical presentation of a patient. Assessment of lung health and patient history are essential to determining the dosage and medications needed for adequate asthmatic symptom control.

Clinical guidelines from reputable organizations, such as the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA), and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) can provide insight into the latest recommendations for asthma management (1, 2). In addition, local laws or health departments might have recommendations for asthma medication guidelines.

What Is the Average Cost for Asthma Medications?

Cost for asthma medications can significantly vary depending on the type of medication, insurance, dosage, frequency, medication administration route, and other factors. Cost is among a leading reason why many patients cannot maintain their medication regime (3). If cost is a concern for your patient, consider reaching out to your local pharmacies or patient care teams to find cost effective solutions for your patients.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some common signs of asthma?

- What are some common medications that can be prescribed to manage asthma?

- What are some factors that can influence asthma development and severity?

Inhaled Corticosteroids Pharmacokinetics

Health care provider professional discretion and patient condition should guide therapy. Consider reviewing a patient’s medication history and health history prior to prescribing asthma medications.

Drug Class – Inhaled Corticosteroids

Commercially available inhaled corticosteroids include: ciclesonide (Alvesco HFA), fluticasone propionate (Flovent Diskus, Flovent HFA, Armon Digihaler), budesonide (Pulmicort Flexhaler), beclomethasone dipropionate (QVAR RediHaler), fluticasone furoate (Arnuity Ellipta), and mometasone furoate (Asmanex HFA, Asmanex Twisthaler).

Clinical criteria for prescribing an inhaled corticosteroid includes adherence to the latest clinical guidelines, patient medical history, patient clinical presentation, and drug availability (4).

Inhaled Corticosteroids Method of Action

Inhaled corticosteroids have an intricate mechanism of action involving several responses to the immune system. Inhaled corticosteroids decrease the existing initial inflammatory response by decreasing the creation and slowing the release of inflammatory mediators. Common inflammatory mediators include histamine, cytokines, eicosanoids, and leukotrienes. Inhaled corticosteroids can also induce vasoconstrictive mechanisms, which, as a result, can lead to less blood flow, resulting in less discomfort and edema (4).

In addition to anti-inflammatory properties, inhaled corticosteroids can create a localized immunosuppressive state that limits the airways’ hypersensitivity reaction, which is thought to reduce bronchospasms and other asthma-associated symptoms. It is important to note that inhaled corticosteroids often do not produce therapeutic effects immediately, as many patients may not see a change in their asthma symptoms for at least a week after beginning inhaled corticosteroid therapy (4).

Inhaled Corticosteroids Side Effects

Every medication has the possibility of side effects, and inhaled corticosteroids are no exception. Common side effects of inhaled corticosteroids include oral candidiasis (thrush), throat irritation, headache, and cough.

Patient education about rinsing their mouth and oral hygiene after use is essential to avoid the possibility of thrush and other oral infections and irritations. More severe side effects can include prolonged immunosuppression, reduction in bone density, and adrenal dysfunction (4).

Inhaled Corticosteroids Alternatives

While there are clinical criteria for asthma medications, everyone can respond to medications differently. Some patients might not report their symptoms alleviating with inhaled corticosteroids, so additional medication, increased dosage, a change in frequency, or a new medication class might need to be considered (4).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some possible side effects of inhaled corticosteroids?

- What are some patient considerations to keep in mind when prescribing inhaled corticosteroids?

Oral Corticosteroids Pharmacokinetics

Health care provider professional discretion and patient condition should guide therapy. Consider reviewing a patient’s medication history and health history prior to prescribing asthma medications.

Drug Class – Oral Corticosteroids

Commercially available oral corticosteroids include methylprednisolone, prednisolone, and prednisone. Clinical criteria for prescribing an oral corticosteroid includes adherence to the latest clinical guidelines, patient medical history, patient clinical presentation, and drug availability (4).

Oral Corticosteroids Method of Action

Methylprednisolone and prednisolone have a method of action as intermediate, long-lasting, synthetic glucocorticoids, have COX-2 inhibitory properties, and inhibit the creation of inflammatory cytokines (5).

Prednisone is a prodrug to prednisolone and has anti-inflammatory and immunomodulating glucocorticoid properties. Prednisone has a method of decreasing inflammation by reversing increased capillary permeability and suppressing the movement of certain leukocytes (6).

Oral Corticosteroids Side Effects

Every medication has the possibility of side effects, and oral corticosteroids are no exception. Methylprednisolone and prednisolone have possible side effects of skin changes, weight gain, increased intraocular pressure, neuropsychiatric events, neutrophilia, immunocompromised state, fluid retention, and GI upset.

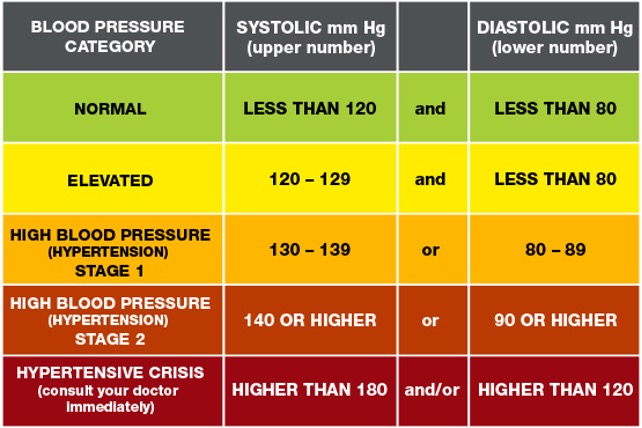

Consider monitoring symptoms and overall health of patients on systemic corticosteroids to assess for long-term side effects (5). Prednisone has possible side effects of changes in blood glucose, changes in sleep habits, changes in appetite, increased bone loss, an immunocompromised state, changes in adrenal function, and changes in blood pressure (6).

Oral Corticosteroids Alternatives

While there are clinical criteria for asthma medications, everyone can respond to medications differently. Some patients might not report their symptoms alleviating with oral corticosteroids, so additional medication, increased dosage, a change in frequency, or a new medication class might need to be considered (6).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some possible side effects of oral corticosteroids?

- What are some patient considerations to keep in mind when prescribing oral corticosteroids versus inhaled corticosteroids?

Short-Acting Beta Agonists (SABAs)

Health care provider professional discretion and patient condition should guide therapy. Consider reviewing a patient’s medication history and health history prior to prescribing asthma medications.

Drug Class – SABAs

Common commercially available SABAs include albuterol sulfate (ProAir HFA, Proventil HFA, Ventolin HFA), albuterol sulfate inhalation powder (ProAir RespiClick, ProAir Digihaler), levalbuterol tartrate (Xopenex HFA), and levalbuterol hydrochloride (Xopenex) (4).

SABAs Method of Action

Short-acting beta-agonists (SABAs) have a rapid onset as broncho-dilating medications. SABAs, especially albuterol in emergent situations, are used often to quickly relax bronchial smooth muscle from the trachea to the bronchioles through action on the β2-receptors.

While SABAs are effective bronchodilators in the short term for asthma symptoms, SABAs do not affect the underlying mechanism of inflammation. As a result, SABAs are often used for short-acting intervals, such as few hours, and have limited capabilities to prevent asthma exacerbations alone (4). SABAs can be administered via meter-dosed inhalers, intravenous, dry powder inhalers, orally, subcutaneously, or via nebulizer.

SABAs Side Effects

Every medication has the possibility of side effects, and SABAs are no exception. Because of the beta receptor agonisms, possible SABA side effects include increased heart rate, chest pain, chest palpitations, body tremors, and nervousness (4). Because of the short half-life of SABAs, chronic side effects are not typically observed.

SABAs Alternatives

While there are clinical criteria for asthma medications, everyone can respond to medications differently. Some patients might not report their symptoms alleviating with SABAs, so additional medication, increased dosage, a change in frequency, or an additional medication class might need to be considered (4).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some possible side effects of short-acting beta agonists?

- What are some patient considerations to keep in mind when prescribing SABAs?

Long-Acting Beta Agonists (LABAs)

Health care provider professional discretion and patient condition should guide therapy. Consider reviewing a patient’s medication history and health history prior to prescribing asthma medications.

Drug Class – LABAs

Common commercially available LABAs are salmeterol and formoterol (7).

LABAs Method of Action

Long-acting beta-agonists (LABAs) have a rapid onset like SABAs, but also have a longer half-life. LABAs are used often as asthma maintenance medications to relax bronchial smooth muscle from the trachea to the bronchioles through action on the β2-receptors. While SABAs are effective bronchodilators in the short term for asthma symptoms, LABAs are effective bronchodilators in the long term for asthma symptoms.

Like SABAs, LABAs do not affect the underlying mechanism of inflammation. LABAs can be administered via meter-dosed inhalers, intravenous, dry powder inhalers, orally, subcutaneously, or via nebulizer. LABAs are often effective for 12-hour durations (7).

LABAs Side Effects

Every medication has the possibility of side effects, and LABAs are no exception. Like SABAs, because of the beta receptor agonisms, possible LABA side effects include increased heart rate, chest pain, chest palpitations, body tremors, and nervousness (7). Other more prolonged side effects can include changes in blood glucose levels and changes in potassium levels with prolonged LABA use (7).

LABAs Alternatives

While there are clinical criteria for asthma medications, everyone can respond to medications differently. Some patients might not report their symptoms alleviating with LABAs, so additional medication, increased dosage, a change in frequency, or an additional medication class might need to be considered (4).

In addition, there are combination inhaled corticosteroid/LABA medications that can be considered, such as fluticasone propionate and salmeterol (Advair Diskus, Advair HFA, AirDuo Digihaler, AirDuo RespiClick, Wixela Inhub), fluticasone furoate and vilanterol (Breo Ellipta), mometasone furoate and formoterol fumarate dihydrate (Dulera), and budesonide and formoterol fumarate dihydrate (Symbicort) (4).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some possible side effects of LABAs?

- What are some patient considerations to keep in mind when prescribing SABAs compared to LABAs?

Long-Acting Muscarinic Antagonists (LAMAs)

Health care provider professional discretion and patient condition should guide therapy. Consider reviewing a patient’s medication history and health history prior to prescribing asthma medications.

Drug Class – LAMAs

Common commercially available LAMAs include two inhalation powders via inhalers known as tiotropium bromide (Spiriva Respimat) and fluticasone furoate, umeclidinium, and vilanterol (Trelegy Ellipta) (4).

LAMAs Method of Action

Both drugs mentioned above are long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs). LAMAs work to alleviate asthmatic symptoms by antagonizing the type 3 muscarinic receptors in bronchial smooth muscles, resulting in relaxation of muscles in the airway (4). Because LAMAs are long-acting, they are not recommended for cases of acute asthma exacerbations or asthmatic emergencies (4).

LAMAs Side Effects

Possible LAMA side effects include urinary retention, dry mouth, constipation, and glaucoma (4).

LAMAs Alternatives

While there are clinical criteria for asthma medications, everyone can respond to medications differently. Some patients might not report their symptoms alleviating with LAMAs, so additional medication, increased dosage, a change in frequency, or an additional medication class might need to be considered (4).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some possible side effects of LAMAs?

- What are some patient considerations to keep in mind when prescribing LAMAs?

Adenosine Receptor Antagonists Pharmacokinetics

Health care provider professional discretion and patient condition should guide therapy. Consider reviewing a patient’s medication history and health history prior to prescribing asthma medications.

Drug Class – Adenosine Receptor Antagonists

The commercially available adenosine receptor antagonist for asthma management is theophylline as a pill or intravenous (8).

Adenosine Receptor Antagonists Method of Action

The method of action for theophylline is acting as a nonselective adenosine receptor antagonist, acting as a competitive, nonselective phosphodiesterase inhibitor, and reducing airway responsiveness to histamine, allergens, and methacholine (8).

Adenosine Receptor Antagonists Side Effects

Common side effects of theophylline include GI upset, headache, dizziness, irritability, and arrythmias (8).

Adenosine Receptor Antagonists Alternatives

While there are clinical criteria for asthma medications, everyone can respond to medications differently. Some patients might not report their symptoms alleviating with theophylline, so additional medication, increased dosage, a change in frequency, or an additional medication class might need to be considered (4).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some possible side effects of adenosine receptor antagonists?

- What are some patient considerations to keep in mind when prescribing adenosine receptor antagonists?

Leukotriene Modifiers Pharmacokinetics

Health care provider professional discretion and patient condition should guide therapy. Consider reviewing a patient’s medication history and health history prior to prescribing asthma medications.

Drug Class – Leukotriene Modifiers

Commercially available leukotriene modifiers include montelukast (Singular) and zafirlukast (Accolate) as oral pills taken once a day. Zileuton (Zyflo CR) is a 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor that also modifies leukotriene activity (4).

Leukotriene Modifiers Method of Action

Montelukast and zafirlukast work to control asthma-related symptoms by targeting leukotrienes, which are eicosanoid inflammatory markers. Montelukast works in particular by blocking leukotriene D4 receptors in the lungs, thus allowing decreased inflammation in the lungs and increased relaxation of lung smooth muscle (9).

Zafirlukast works by being a competitive antagonist at the cysteinyl leukotriene-1 receptor (CYSLTR1) (10). Zileuton is a 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor, in which 5-lipoxygenase is needed for leukotriene creation. Blocking 5-lipoxygenase decreases the formation of leukotrienes at several receptors. As a result of decreased leukotriene production, there is decreased inflammation, decreased mucus secretion, decreased bronchoconstriction (11).

Leukotriene Modifiers Side Effects

Possible side effects of montelukast include headaches, GI upset, and upset. Neuropsychiatric events, such as nightmares, changes in sleep, depression, and suicidal ideation are more severe side effects associated with montelukast.

Possible side effects of zafirlukast include headache, GI upset, and hepatic dysfunction (9).

Possible side effects of zileuton include hepatic dysfunction, changes in sleep, changes in mood, headaches, and GI upset. When the leukotriene modifiers, neuropsychiatric side effects are to be monitored for in particular, especially for suicidal ideation (9,10,11).

Leukotriene Modifiers Alternatives

Some patients might not report their symptoms alleviating with leukotriene modifiers, so additional medication, increased dosage, a change in frequency, or an additional medication class might need to be considered (4).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some possible side effects of leukotriene modifiers?

- What are some patient considerations to keep in mind when prescribing leukotriene modifiers?

Mast Cell Stabilizer Pharmacokinetics

Health care provider professional discretion and patient condition should guide therapy. Consider reviewing a patient’s medication history and health history prior to prescribing asthma medications.

Drug Class – Mast Cell Stabilizer

A commercially available mast cell stabilizer is cromolyn available via metered-dose inhaler and nebulizer solution (12).

Mast Cell Stabilizer Method of Action

Cromolyn has a method of action in which it inhibits the release of inflammatory mediators from cells, such as the release of histamine and leukotrienes (12).

Mast Cell Stabilizer Side Effects

Every medication has the possibility of side effects, and cromolyn is no exception. Common side effects of cromolyn include dry throat, throat irritation, drowsiness, dizziness, cough, headache, and GI upset (12).

Mast Cell Stabilizer Alternatives

While there are clinical criteria for asthma medications, everyone can respond to medications differently. Some patients might not report their symptoms alleviating with mast cell stabilizers, so additional medication, increased dosage, a change in frequency, or an additional medication class might need to be considered (4).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some possible side effects of mast cell stabilizers?

- What are some patient considerations to keep in mind when prescribing mast cell stabilizers?

Monoclonal Antibody Pharmacokinetics

Health care provider professional discretion and patient condition should guide therapy. Consider reviewing a patient’s medication history and health history prior to prescribing asthma medications.

Drug Class – Monoclonal Antibody

Commercially available monoclonal antibodies include Omalizumab (Xolair), mepolizumab (Nucala), reslizumab (Cinqair), benralizumab (Fasenra), dupilumab (Dupixent), and tezepelumab-ekko (Tezspire). Omalizumab, mepolizumab, benralizumab, dupilumab, and texepelumab-ekko are available via subcutaneous injection. Reslizumab is available via intravenous solution (4).

Monoclonal Antibody Method of Action

Omalizumab is an anti-IgE monoclonal antibody that works by inhibiting the binding of IgE to mast cells and basophils. As a result of decreased bound IgE, activation and release of mediators, such as histamine, in the allergic response are decreased (13).

Mepolizumab, reslizumab, and benralizumab are interleukin (IL)-5 antagonists. These IL-5 antagonists inhibit IL-5 signaling, allowing for a decrease in the creation and survival of eosinophils. However, the full method of action for IL-5 antagonists is still unknown, as more evidence-based research is needed (4, 15).

Dupilumab is an IgG4 antibody that inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 signaling by binding to the IL-4Rα subunit. This inhibition of the IL-4Rα subunit allows for the decrease of IL-4 and IL-13 cytokine-induced inflammatory responses (14).

Tezepelumab-ekko is an IgG antibody that binds to the thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and prevents TSLP from interacting with the TSLP receptor. Blocking TSLP decreases biomarkers and cytokines associated with inflammation. Knowing this, the full method of action for Tezepelumab-ekko is still unknown, as more evidence-based research is needed4,15.

Monoclonal Antibody Side Effects

Possible side effects of omalizumab include injection site reactions, fracture, anaphylaxis, headache, and sore throat (13). Possible side effects of mepolizumab, reslizumab, and benralizumab include injection site reactions, headache, and hypersensitivity reactions (4). Possible side effects of dupilumab include joint aches, injection site reactions, and headache (14). Possible side effects of tezepelumab-ekko include injection site reactions and headache (14).

Monoclonal Antibody Alternatives

While there are clinical criteria for asthma medications, everyone can respond to medications differently. Some patients might not report their symptoms alleviating with monoclonal antibodies, so additional medication, increased dosage, a change in frequency, or an additional medication class might need to be considered (4).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some possible side effects of monoclonal antibodies?

- What are some patient considerations to keep in mind when prescribing monoclonal antibodies?

Nursing Considerations

Nurses remain the most trusted profession for a reason, and APRNs are often pillars of patient care in several health care settings. Patients turn to nurses for guidance, education, and support. While there is no specific guideline for the nurses’ role in asthma education and management, here are some suggestions to provide quality care for patients currently taking medications to manage asthma or concerned about possibly having asthma.

- Take a detailed health history. Often times, respiratory symptoms, such as a cough or trouble breathing, are often dismissed in health care settings, or seen as “common symptoms with everyone.” If a patient is complaining of symptoms that could be related to asthma, inquire more about that complaint.

Ask about how long the symptoms have lasted, what treatments have been tried, if these symptoms interfere with their quality of life, and if anything alleviates any of these symptoms. If you feel like a patient’s complaint is not being taken seriously by other health care professionals, advocate for that patient to the best of your abilities.

- Review medication history at every encounter. Often times, in busy clinical settings, reviewing health records can be overwhelming. Millions of people take asthma medications at varying dosages, frequencies, and times of day. Many people with asthma take more than one medication to manage their symptoms.

Ask patients how they are feeling on the medication, if their symptoms are improving, and if there are any changes to medication history.

- Be willing to answer questions about asthma, respiratory health, and medication options. Society stigmatizes open discussions of prescription medication and can minimize symptoms of asthma, such as a chronic cough.

There are many people who do not know about medication options or the long-term effects of undiagnosed or poorly managed asthma. Be willing to be honest with yourself about your comfort level discussing topics and providing education on asthma medications and asthma clinical assessment options.

- Inquire about a patient’s life outside of medications, such as their occupation, living situation, and smoking habits. Household exposures, such as carpets or pets, can trigger asthma. Occupations with high exposure to smoke can also trigger asthmatic symptoms. Smoking, living with someone who smokes, or residing in an area with high levels of pollution can also influence asthma symptoms.

Discuss possible solutions to help with symptoms, such as improving ventilation, increasing air quality, and mask wearing when possible.

- Communicate the care plan to other staff involved for continuity of care. For several patients, especially for patients with severe asthma, care often involves a team of nurses, specialists, pharmacies, and more. Ensure that patients’ records are up to date for ease in record sharing and continuity of care.

- Stay up to date on continuing education related to asthma medications, as evidence-based information is always evolving and changing. You can then present your new learnings and findings to other health care professionals and educate your patients with the latest information. You can learn more about the latest research on asthma and asthma-related medications by following updates from evidence-based organizations.

How can nurses identify if someone has asthma?

Unfortunately, it is not always possible to look at someone with the naked eye and determine if they have asthma. While some people might have visible asthmatic symptoms, such as wheezing or trouble breathing, asthmatic clinical presentation can significantly vary from person to person.

APRNs can identify and diagnose if someone has asthma by taking a complete health history, listening to patient’s concerns, and offering pulmonary function testing.

What should patients know about asthma medications?

Patients should know that anyone has the possibility of experiencing side effects medications for asthma management, just like any other medication. Patients should be aware that if they notice any changes in their mood, experience any sharp headaches, or feel like something is a concern, they should seek medical care.

Nurses should also teach patients to advocate for their own health in order to avoid untreated or undetected asthma and possible chronic complications from asthma or asthma-related medications.

Here are important tips for patient education in the inpatient or outpatient setting:

- Tell the health care provider of any existing medical conditions or concerns (need to identify risk factors).

- Tell the health care provider of any existing lifestyle concerns, such as tobacco use, other drug use, sleeping habits, occupation, diet, menstrual cycle changes (need to identify lifestyle factors that can influence asthmatic medication use, asthma severity, and asthma management).

- Tell the health care provider if you have any changes in your breathing, such as pain with deep breathing or persistent coughing (potential asthma exacerbation symptoms or possibility of asthma medications not being as effective for treatment).

- Tell the nurse of health care provider if you experience any pain that increasingly becomes more severe or interferes with your quality of life.

- Keep track of your health, medication use, and health concerns via an app, diary, or journal (self-monitoring for any changes).

- Tell the health care provider right away if you are having thoughts of hurting yourself or others (possible increased risk of suicidality is a possible side effect for montelukast use).

- Take all prescribed medications as indicated and ask questions about medications and possible other treatment options, such as non-pharmacological options or surgeries.

- Tell the health care provider if you notice any changes while taking medications or on other treatments to manage asthma (potential worsening or improving health situation).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some problems that can occur if medications are not asthma properly?

- What are some possible ways you can obtain a detailed, patient centric health history?

- What are some possible ways APRNs can educate patients on asthma and air quality?

Research Findings

What Research on Asthma Medication Exists Presently?

There is extensive publicly available literature on asthma and asthma-related medications via the National Institutes of Health and other evidence-based journals (1,2,4).

What are some ways for people who take asthma medications to become a part of research?

If a patient is interested in participating in clinical trial research, they can seek more information on clinical trials from local universities and health care organizations.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some reasons someone would want to enroll in clinical trials?

Conclusion

Asthma is a chronic condition that affects many people from their childhood to their aging years. As more medications for asthma come onto the market and more evidence-based approaches to asthma and lung care emerge, APRNs will be at the forefront of primary care and asthma care across the lifespan.

Case Study #1

Susie is a mom to a 15-year-old named Jill. She arrives at the pediatric asthma and allergy specialist practice for a new patient visit. Susie reports that she notices Jill is having trouble sleeping at night and coughing more during the day for the past month. Jill plays soccer with her school, but her mom is concerned about coughing and trouble sleeping interfering with her sports.

Susie knows that her dad has asthma, and Jill spends a lot of time with her aunt who smokes cigarettes. Jill has a history of generalized anxiety disorder and reports no smoking, no drinking, and no recreational drugs. Jill also wants to learn more about her lung health, as she wants to play soccer professionally one day.

- What are some specific questions you’d want to ask about Jill’s coughing and respiratory health?

- What are health history questions you would want to highlight?

- What are some tests or lab work would you suggest performing?

Case Study #2 (Continued)

Susie also shares that she is dating a new partner who vapes in the home, and they recently got a pet puppy in the home. She states that Jill had trouble sleeping at night and coughing a lot when she was younger, but Susie thought Jill grew out of it. Susie wants to learn more about if Jill has asthma like her grandfather, if there are any ways to manage this cough, and if there are any tests that can determine Jill’s lung health in the office today.

- What sort of tests can be done in-office to assess pulmonary function?

- What sort of environmental exposures can trigger respiratory conditions?

Susie agrees to have Jill do allergy testing and to do an in-office pulmonary function test for teenagers. Jill also wants to learn more about spirometry that you mentioned earlier and how to monitor her health outside of the office since she’s busy with school and soccer and doesn’t want to come to the office every time there’s a problem.

Susie is open to medication options for Jill but doesn’t want anything that will interfere too much with Jill’s social time with her friends. Susie and Jill also want to know if this is a health condition that Jill will have forever or if Jill will grow out of this.

- Knowing Susie’s concerns and Jill’s age, what are some talking points about reducing possible asthma triggers?

- How would you explain asthma as a chronic health condition to an adolescent patient?

- Given Jill and Susie’s concerns about medications, what would be some possible medication options to consider after reviewing Jill’s pulmonary function test results and patient history?

SSRI Use in Major Depressive Disorder

Introduction

When hearing the phrase selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, what comes to mind? If you’re an advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) with prescriptive authority, you’ve heard of SSRIs before. Even as a nurse or maybe before nursing school, conversations about prescription drug use and mental health existed every so often.

Presently, patients seek guidance and information on various health topics from APRNs, including medication management, women’s health, and mental health. The information in this course will serve as a valuable resource for APRNs with prescriptive authority of all specialties, education levels, and backgrounds to learn more about SSRIs and major depressive disorder (MDD).

Defining SSRIs

What Are SSRIs?

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, known as SSRIs, are a type of pharmacological drug class. SSRIs have existed for the past several decades as a class of prescription medications that can manage major depressive disorder (MDD) and other mental health conditions (1).

While this course focuses explicitly on SSRI use in MDD management, SSRIs are also Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved to manage obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorder (PD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and social anxiety disorder (SAD). In addition, several off-label uses for SSRI include management for binge eating disorder and menopausal vasomotor symptoms.

How and Where Are SSRIs Used?

SSRIs are commonly prescribed to manage MDD and other mood disorders in the U.S. and around the world in pediatric, adult, and geriatric populations (1, 2). SSRIs can be taken by mouth as a pill, capsule, or liquid oral solution. Presently, SSRIs cannot be offered via intravenous, rectal, buccal, or injection routes.

What Is the Clinical Criteria for Prescribing SSRIs?

Clinical criteria for prescribing SSRIs can vary depending on the intention for the SSRI. In the case of MDD, several factors can play a role in the clinical criteria for prescribing SSRIs. A patient’s adherence to swallowing a pill daily, dosage given the patient’s weight, medical history, and MDD concerns, and prior experience with other medications can influence prescribing SSRIs. When considering prescribing SSRIs for MDD management, consider assessing the patient for MDD first, taking a detailed health history, and discussing the risk versus benefits of starting SSRIs for this patient (1, 3).

What Is the Average Cost for SSRIs?

Cost for SSRIs can significantly vary depending on the type of SSRI, insurance, dosage, frequency, and other factors. Cost is among leading reasons why many patients cannot maintain their medication regime (4). If cost is a concern for your patient, consider reaching out to your local pharmacies or patient care teams to find cost-effective solutions for your patients.

What Is Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)?

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a mental health condition in which a person has consistent appetite changes, sleep changes, psychomotor changes, decreased interest in activities, negative thoughts, suicidal thoughts, and depressed mood that interfere with a person’s quality of life (5). According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders, a patient must have at least five persistent mood related symptoms, including depression or anhedonia (loss of interest in activities once enjoyed), that interferes with a person’s quality of life to be formally diagnosed with MDD. Note that MDD does not include a history of manic episodes, and pediatric populations can present with more variable MDD symptoms (5). As an APRN, you can assess for MDD by doing a detailed patient health history or having a patient complete the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) – a depression assessment tool (5).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some medication administration options for SSRIs?

- What populations can be prescribed SSRIs?

SSRI Pharmacokinetics

Drug Class SSRIs

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, known as SSRIs, are a type of pharmacological drug class part of the antidepressant drug class. They can be prescribed at various dosages depending on the patient history, severity of major depressive disorder (MDD), other medication use, and other factors based on patient-centered decision making. Currently, SSRIs that are FDA approved for MDD management include paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram, vilazodone, and fluoxetine. SSRIs can be prescribed for the oral route and are available via capsule, tablet, or liquid suspension/solution. SSRIs can be taken at any time of day. They can be taken with or without food, though vilazodone in particular is recommended with food. SSRIs are often prescribed to be taken once a day, sometimes twice a day, depending on the severity of MDD. Health care provider professional discretion and patient condition should guide therapy (1).

SSRIs are metabolized by and known to affect the cytochrome P450 system. CYP2D6 inhibitors include escitalopram, citalopram, sertraline, paroxetine, and fluoxetine. Fluoxetine and fluvoxamine are inhibitors of CYP2C19. Fluvoxamine is an inhibitor of CYP1A2. Consider reviewing a patient’s medication history and health history prior to prescribing SSRIs (1).

SSRIs Method of Action

SSRI method of action has been subject to several studies, especially in the last few years. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that plays a role in mood and other bodily functions. It can be measured in plasma, blood, urine, and CSF (6). It is important to note that serotonin is rapidly metabolized to 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) (6). SSRIs work by inhibiting the reuptake of serotonin at certain chemical receptors, thereby increasing serotonin activity and concentration (1). SSRIs inhibit the serotonin transporter (SERT) at the presynaptic axon terminal.

By obstructing the SERT, a higher amount of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5HT) remains in synaptic clefts. This higher amount of serotonin can then stimulate postsynaptic receptors for a more extended period (1). While SSRIs can increase serotonin activity, there is some evidence that suggests the possibility of long-term SSRI use reducing serotonin concentration (6). In addition, the clinical response to SSRIs in patients with MDD can take anywhere from a few to several weeks to emerge (7). While some research suggests that there are initial improvements in mood, evidence remains inconclusive as to the exact time SSRIs can take to provide a therapeutic response for patients (7). Also, while research suggests that SSRIs can increase serotonin levels, there is still mixed evidence on the exact method of action for SSRIs (7).

As a result, it is important to counsel patients that SSRIs can take a few weeks to provide a therapeutic response and to monitor mood and symptoms while taking SSRIs.

SSRI Side Effects

Every medication has the possibility of side effects, and SSRIs are no exception. Fortunately, SSRIs are known to have less side effects than other drug classes of antidepressants, such as monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) or tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). The most commonly known side effects of SSRIs include weight gain, sleep changes, headache, gastrointestinal issues, drowsiness, orthostatic hypotension, and sexual function changes (1).

Sleep changes can include an increased desire to sleep, increase in the amount of time sleeping, or insomnia. Gastrointestinal issues can include an upset stomach, nausea, or dry mouth. Mood changes, such as anxiety, are possible side effects as well. Sexual function changes can include erectile dysfunction, libido changes, impaired orgasmic response, and vaginal dryness (1, 8).

There are more serious possible side effects of SSRIs as well. For instance, SSRIs have the possible side effect of QT prolongation, which if left untreated or undiagnosed, can lead to fatal cardiac arrythmias (1, 8). In particular, the SSRI citalopram has been shown to have more of a risk for QT prolongation compared to other SSRIs. Also, like any other medication that can possibly increase levels of serotonin in the body, there is a possibility of serotonin syndrome as a complication of SSRI use. Possible serotonin syndrome clinical manifestations include increased blood pressure, increased sweating, increased reflex ability, and increased dry eyes (8). Due to the wide varied range of side effects, patient counseling, monitoring, and education is essential when prescribing SSRIs.

SSRI Black Box Warning

In 2004, the FDA issued a black box warning for SSRIs and other antidepressant medications due to the possible increased risk of suicidality in pediatric and young adult populations (up to age 25). When considering SSRI use in patients under 25 and knowing MDD is a risk factor for suicidality, having a conversation with the patient about risks versus benefits must be considered. However, in the past several years since the FDA’s warning, there is no clear evidence showing a correlation between SSRIs and the increased risk of suicidality (1, 8). Health care provider professional discretion and patient condition should guide therapy.

SSRI Alternatives

MDD can be a complex, chronic condition to manage with varying clinical presentation and influence on a patient’s quality of life. There are several alternatives to SSRI use, such as: (1, 9)

- Other prescription drugs

- Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). Commonly known SNRIs include milnacipran, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, and levomilnacipran.

- Atypical antidepressants. Commonly known atypical antidepressants include bupropion and mirtazapine.

- Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). Commonly known TCAs include amitriptyline, desipramine, imipramine, clomipramine, doxepin, and nortriptyline.

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). Commonly known MAOIs include phenelzine, tranylcypromine, isocarboxazid, and selegiline.

- Psychotherapy, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or interpersonal therapy

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

- Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS)

- Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS)

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some possible side effects of SSRIs?

- What are some pharmacological alternatives to SSRIs?

Nursing Considerations

Nurse’s Role

What Is the Nurses’ Role in SSRI Patient Education and Management?

Nurses remain the most trusted profession for a reason, and APRNs are often pillars of patient care in several health care settings. Patients turn to nurses for guidance, education, and support. While there is no specific guideline for the nurses’ role in SSRI education and management, here are some suggestions to provide quality care for patients interested in or currently taking SSRIs to manage current or suspected major depressive disorder (MDD).

- Take a detailed health history. Often times, mental health symptoms, such as depressive thoughts or anxiety, are often dismissed in health care settings, even in mental health settings. If a patient is complaining of symptoms that could be related to major depressive disorder, inquire more about that complaint. Ask about how long the symptoms have lasted, what treatments have been tried, if these symptoms interfere with their quality of life, and if anything alleviates any of these symptoms. If you feel like a patient’s complaint is not being taken seriously by other health care professionals, advocate for that patient to the best of your abilities.

- Review medication history at every encounter. Often times, in busy clinical settings, reviewing health records can be overwhelming. While a vast number of people take SSRIs, many are no longer benefiting from the medication. Ask patients how they are feeling on the medication, if their symptoms are improving, and if there are any changes to medication history.

- Ask about family history. If someone is complaining of symptoms that could be related to MDD, ask if anyone in their immediate family, such as their parent or sibling, experienced similar conditions.

- Be willing to answer questions about mental health and SSRIs. Society can often stigmatize open discussions of prescription medication and mental health. SSRIs are no exception. There are many people who do not know about the benefits and risks of SSRIs, the long-term effects of unmanaged MDD, or possible treatment options. Be willing to be honest with yourself about your comfort level discussing topics and providing education on SSRIs and MDD.

- Communicate the care plan to other staff involved for continuity of care. For several patients, MDD management often involves a team of mental health professionals, nurses, primary care specialists, pharmacies, and more. Ensure that patients’ records are up to date for ease in record sharing and continuity of care.

- Stay up to date on continuing education related to SSRIs and mental health conditions, as evidence-based information is always evolving and changing. You can then present your new findings to other health care professionals and educate your patients with the latest information. You can learn more about the latest research on SSRIs and mental health by following updates from evidence-based organizations.

Identifying Major Depressive Disorder

How can nurses identify if someone has major depressive disorder?

Unfortunately, it is not possible to look at someone with the naked eye and determine if they have MDD. APRNs can identify and diagnose if someone has MDD by taking a complete health history, listening to patient’s concerns, having patients complete the PHQ-9 questionnaire and communicating any concerns to other health care professionals (9).

Patient Education

What should patients know about SSRIs?

Patients should know that anyone has the possibility of experiencing side effects of SSRIs, just like any other medication. Patients should be aware that if they notice any changes in their mood, experience any sharp headaches, or feel like something is a concern, they should seek medical care. Due to social stigma associated with mental health and SSRI use, people may be hesitant to seek medical care for fear of being dismissed by health care professionals (1, 6). In addition, side effects (that interfere with the quality of life) are often normalized (1, 6). However, as more research and social movements discuss mental health and SSRI use more openly, there is more space and awareness for SSRI use and mental health.

Nurses should also teach patients to advocate for their own health in order to avoid progression of MDD and possible unwanted side effects of SSRIs. Here are important tips for patient education in the inpatient or outpatient setting.

- Tell the health care provider of any existing medical conditions or concerns (need to identify risk factors)

- Tell the health care provider of any existing lifestyle concerns, such as alcohol use, other drug use, sleeping habits, diet, menstrual cycle changes (need to identify lifestyle factors that can influence SSRI use and MDD)

- Tell the health care provider if you notice any changes in your mood, behavior, sleep, sexual health (including vaginal dryness or erectile dysfunction), or weight (possible changes that could hint at more chronic side effects of SSRIs)

- Tell the health care provider if you have any changes in urinary or bowel habits, such as increased or decreased urination or defecation (potential risk for SSRI malabsorption or possible unwanted side effects)

- Tell the nurse of health care provider if you experience any pain that increasingly becomes more severe or interferes with your quality of life

- Keep track of your mental health, medication use, and health concerns via an app, diary, or journal (self-monitoring for any changes)

- Tell the health care provider right away if you are having thoughts of hurting yourself or others (possible increased risk of suicidality is a possible side effect for SSRI use)

- Take all prescribed medications as indicated and ask questions about medications and possible other treatment options, such as non-pharmacological options or surgeries

- Tell the health care provider if you notice any changes while taking medications or on other treatments to manage your MDD (potential worsening or improving mental health situation)

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some possible ways you can obtain a detailed, patient centric health history?

- What are some possible ways APRNs can educate patients on SSRIs and major depressive disorder?

Research Findings

What Research on SSRIs exists presently?

There is extensive publicly available literature on SSRIs via the National Institutes of Health and other evidence-based journals.

What are some ways for people who take SSRIs to become a part of research?

If a patient is interested in participating in clinical trial research, they can seek more information on clinical trials from local universities and health care organizations.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some problems that can occur if SSRIs are not managing major depressive disorder symptoms adequately?

- What are some reasons someone might want to enroll in SSRI clinical trials?

Case Study

Case Study Part 1

Susan is a 22-year-old Black woman working as a teacher. She arrives for her annual exam at the local health department next to her place of work. She reports nothing new in her health, but she says she’s been feeling more tired over the past few months. Susan reports having some trouble sleeping and trouble eating but doesn’t feel too stressed overall. She heard one of her friends talking about SSRIs and wants to try them, but she’s never taken prescription medications long-term before. She also thinks she might have some depression because she looked at some forums online and resonated with a lot of people’s comments.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some specific questions you’d want to ask about her mental health?

- What are some health history questions you’d want to highlight?

- What lab work would you suggest performing?

Case Study Part 2

Susan agrees to complete bloodwork later this week and thinks she might have a family history of depression. She said that no one in her family talks about mental health, but she heard about depression from her friends recently and family a long time ago. She’s back in the office a few weeks later, and her labs are within normal limits. Susan states she’s still feeling fatigued and feeling a bit more hopeless these days. She denies thinking about hurting herself or others.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How would you discuss Susan’s mental health concerns?

- How would you explain to Susan the influence of lifestyle, such as sleep, diet, and environment, on mood?

Case Study Part 3

Susan completed the PHQ-9 questionnaire and had a high score. After discussing her responses with her, you diagnose her with MDD. Susan admits that she is open to trying SSRIs. She is also open to seeing a therapist, as she states that she’s never been to therapy. She would like resources on any therapy services, medication options, and non-pharmacological options to help her manage her condition.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Knowing Susan’s concerns, what are some possible non-pharmacological management options for her MDD?

- What are some major SSRI side effects to educate Susan on?

Conclusion

Major depressive disorder is a complex chronic health condition that affects many people nationwide. SSRIs are often a first-line pharmacological option for MDD management. However, clinical presentation and symptom management with SSRIs can vary widely. While some patients would prefer a low-dose SSRI, others will need a higher dose and possible extra medication management. Education and awareness of SSRIs can influence the lives of many people.

Safe Prescribing of Opioids

Introduction

For centuries, humans have been using, developing, and synthesizing opioid compounds for pain relief. Opioids are essential for treating patients who are experiencing severe and sometimes even moderate pain. Chronic pain can negatively affect our lives. In 2011, the cost of chronic pain ranged from $560 to $635 billion in direct medical expenses, lost productivity, and disability. An estimated one in five U.S. adults had chronic pain (11).

Introduction of opioid drug class, indications for use, most prescribed opioids, and their effects.

Opioids usually bind to mu-opioid receptor sites, where they have agonist effects, providing pain relief, sedation, and sometimes feelings of euphoria. Opiates refer only to natural opioids derived from the poppy plant. The term "opioids" includes all-natural, semi-synthetic, and synthetic opioids.

Opioids are classified into several categories based on their origin and chemical structure:

- Natural Opioids (Opiates): These come from the opium poppy plant. Examples include morphine and codeine.

- Semi-Synthetic Opioids: These are natural opioids that are chemically modified. Examples include drugs like oxycodone, hydrocodone, oxymorphone, and hydromorphone.

- Synthetic Opioids: These opioids are entirely synthesized in a laboratory and do not have a natural source. Examples include fentanyl, tramadol, and methadone (4).

Providers must always caution patients about the benefits and risks. The main advantage of opioid medication is that it will reduce pain and improve physical function. A provider may use a 3-item Pain, Enjoyment of Life, and General Activity (PEG) Assessment Scale:

- What number best describes your pain on average in the past week?

- What number best describes how, during the past week, pain has interfered with your enjoyment of life?

- What number best describes how, during the past week, pain has interfered with your general activity?

The desired goal is a 30% improvement overall with opioid treatment. (Centers for Disease and Control)

Providers must also go over potential side effects and warnings. Side effects include sedation, dizziness, confusion, nausea, vomiting, constipation, itching, pupillary constriction, and respiratory depression. Providers should discuss the importance of taking medication as prescribed. Taking opioids in larger than prescribed dosage, or in addition to alcohol, other illicit substances, or prescription drugs, can lead to severe respiratory depression and death. Individuals should not drive when taking opioids due to the sedating effects and decreased reaction times.

There are now thousands of different Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved opioids available for providers to prescribe. They can be administered via other routes and come in various potencies. The strength of morphine is the "gold standard" used when comparing opioids. A morphine milligram equivalent (MME) is the degree of µ-receptor agonist activity. The following is a sample of some of the most prescribed opioids and their MME:

| Opioid | Conversion factor | Opioid | Conversion factor |

| Codeine | 0.15 | Morphine | 1.0 |

| Fentanyl transdermal (in mcg/hr) | 2.4 | Oxycodone | 1.5 |

| Hydrocodone | 1.0 | Oxymorphone | 3.0 |

| Hydromorphone | 5.0 | Tapentadol† | 0.4 |

| Methadone | 4.7 | Tramadol§ | 0.2 |

To utilize this information, multiply the dose for each opioid by the conversion factor to determine the quantity in MMEs. For example, tablets containing hydrocodone 5 mg and acetaminophen 325 mg taken four times a day would include a total of 20 mg of hydrocodone daily, equivalent to 20 MME (11).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How often do you prescribe opioids to your patients? If so, which ones and what dosages?

- If you do not prescribe opioids, do you treat patients taking them?

- Have you ever felt hesitant about prescribing opioids? What were the reasons?

- What topics do you routinely cover when you discuss opioid prescriptions with your patients?

- Do you know how to determine if a patient is engaging in opioid-seeking behaviors?

A history of opioids leading to the current epidemic

While the current opioid epidemic has caused devastating effects in recent years, destruction from opioids has been going on for centuries. In the early 1800s, physicians and scientists became aware of the addictive qualities of opium. This finding encouraged research to develop safer ways to deliver opioids for pain relief and cough suppression, which led to the development of morphine. By the mid-1800s, with commercial production and the invention of the hypodermic needle, morphine became easier to administer.

During the Civil War (1861 to 1865), injured soldiers were sometimes treated with morphine, and some developed lifelong addictions after the war. Without other options for pain relief, physicians kept giving patients morphine as treatment. Early indicators that morphine should be used cautiously were largely ignored. Between 1870 and 1880, the use of morphine tripled. Even with the problems associated with opioids, they continued to serve a vital part in the pain treatment of patients, and their use and development continued (6).

Opioid prescribing increased fourfold during 1999–2010. Along with the increase in opioid prescriptions during this time, how they were prescribed also changed; opioids were increasingly prescribed at higher dosages and for longer durations. The number of people who reported using OxyContin for non-medical purposes increased from 400,000 in 1999 to 1.9 million in 2002 and to 2.8 million in 2003. This was accompanied by an approximately fourfold increase in overdose deaths involving prescription opioids (8).

In 2020, approximately 1.4 million people were diagnosed with opioid use disorder (OUD), of those associated with opioid painkillers, as opposed to 438,000 who have heroin-related OUD (1, 4). Over 100,000 people died of a drug overdose, with 85% involved in an opioid (1, 4).

Widespread efforts were made to combat this growing issue. The prescribing rate peaked and leveled off from 2010-2012 and has been declining since 2012. In 2021, an estimated 2.5 million adults had been diagnosed with OUD. However, the amount of MME of opioids prescribed per person is still around three times higher than in 1999 (5).

Controlled Substances

On July 1, 1973, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was established in the United States. The Diversion Control Division oversees pharmaceuticals. Within this Division are five levels of controlled substances, which classify illicit and medicinal drugs (7).

Schedule I Controlled Substances

No medical use, lack of accepted safety for use under medical supervision, and high abuse potential.

Examples of Schedule I substances are heroin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and marijuana (cannabis).

Schedule II/IIN Controlled Substances (2/2N)

High potential for abuse, which can lead to severe dependence.

Examples include hydromorphone, methadone, meperidine, oxycodone, and fentanyl. Other narcotics in this class include morphine, opium, codeine, and hydrocodone.

Some examples of Schedule IIN stimulants include amphetamine, methamphetamine, and methylphenidate.

Other substances include amobarbital, glutethimide, and pentobarbital.

Schedule III/IIIN Controlled Substances (3/3N)

Less potential for abuse than substances in Schedules I or II, and abuse may lead to moderate or low physical dependence or high psychological dependence.

Include drugs containing not more than 90 milligrams of codeine per dosage unit like Acetaminophen with Codeine and buprenorphine.

Schedule IN non-narcotics includes benzphetamine, phendimetrazine, ketamine, and anabolic steroids such as Depo®-Testosterone.

Schedule IV Controlled Substances

Have a low potential for abuse relative to substances in Schedule III.

Examples include alprazolam, carisoprodol, clonazepam, clorazepate, diazepam, lorazepam, midazolam, temazepam, and triazolam, Tramadol.

Schedule V Controlled Substances

Low potential for abuse relative to Schedule IV and primarily consist of medications that have small quantities of narcotics.

Examples include cough preparations containing not more than 200 milligrams of codeine per 100 milliliters or per 100 grams and ezogabine (10).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How have your prescribing practices of opioids changed in response to the epidemic over time?

- What trends have you noticed in overall inpatient treatment plans regarding opioid prescribing trends (e.g., dose changes? or increase in opioid alternative therapies?)

- Do you think there is a stigma surrounding patients who are currently using opioids?

Explore behaviors that indicate opioid seeking, misuse, or addiction in patients.

Opioid use disorder (OUD) causes significant impairment or distress. Diagnosis is based on the following criteria: unsuccessful efforts to reduce or control use or use that leads to social problems and a failure to fulfill obligations at work, school, or home. The term Opioid Use Disorder is the preferred term; "opioid abuse or dependence" or "opioid addiction" have negative connotations and should be avoided. (3).

OUD occurs after a person has developed tolerance and dependence, resulting in a physical challenge to stop opioid use and increasing the risk of withdrawal. Tolerance happens over time when a person experiences a reduced response to medication, requiring a larger amount to experience the same effect. Opioid dependence occurs when the body adjusts to regular opioid use. Unpleasant physical symptoms of withdrawal occur when medication is stopped. Symptoms of withdrawal include anxiety, insomnia, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, etc. (5).

Patients who have OUD may or may not have practiced drug misuse. Drug misuse, the preferred term for "substance abuse," is the use of illegal drugs and the use of prescribed drugs other than as directed by a doctor, such as using more amounts, more often, or longer than recommended or using someone else's prescription (3).

Some indications that a patient may be starting to have unintended consequences with their opioid prescription may include the following symptoms: craving, wanting to take opioids in higher quantities or more frequently, difficulty controlling use, or work, social, or family issues. If providers suspect OUD, they should discuss their concerns with their patients nonjudgmentally and allow the patient to disclose related concerns or issues. Providers should assess the presence of OUD using the DSM-5 criteria.

Providers can use validated screening tools such as:

- Urine and oral fluid toxicology testing

- Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST)

- Tobacco, Alcohol, and/or other Substance use Tools (TAPS)

- A three-question version of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C)

The following patients are at higher risk for OUD or overdose:

- History of depression or other mental health conditions

- History of a substance use disorder

- History of overdose

- Taking 50 or greater MME/day or taking other central nervous system depressants with opioids

Self Quiz

Ask yourself…

- How often do you have patients exhibiting symptoms of OUD in your practice setting?

- What would your next steps be if you identify a patient with potential OUD (e.g., additional screening, referral, or treatment plans)?

- Have you noticed any trends in patients presenting with OUD? Such as socioeconomic status, occupation, gender, race, and medical diagnosis.

The 12 components of the CDC’s recent guidelines for opioid prescribing.

In 2022, the CDC updated the 2016 guidelines to help prescribers navigate prescribing opioids amid an epidemic. These guidelines are directed toward prescribing medications to adults to be taken in the outpatient setting, for example, primary care clinics, surgery centers, urgent cares, and dental offices. These do not apply to providers caring for individuals with sickle-cell disease, cancer, those receiving inpatient care, or end-of-life or palliative care. They are also intended to serve as a guideline, and each treatment plan should be specific to the unique patient and circumstances.

Some of the Goals of the guidelines are to:

- Improve communication between providers and patients about treatment options and discuss the benefits and risks before initiating opioid therapy.

- Improve the effectiveness and safety of treatment to improve quality of life.

- Reduce risks associated with opioid treatment, including opioid use disorder (OUD), overdose, and death.

Recommendation #1: Determining when it is appropriate to initiate opioids for pain.

An essential part of the prescribing process is determining the anticipated pain severity and duration based on the patient’s diagnosis. Pain severity can be classified into three categories when measured using the standard 1-10 numeric scale. Pain scores 1-4 are considered mild, 5-6 are moderate, and 7-10 severe. Opioids are typically used for moderate to severe pain.

The patient’s diagnosis will allow the provider to determine if pain initially falls into one of the following three categories of anticipated duration: acute, subacute, and chronic. Acute pain is expected to last for one month or less. Acute pain often is caused by injury, trauma, or medical treatments such as surgery. Unresolved acute pain may develop into subacute pain if not resolved in 1 month. If pain exceeds three months, it is classified as chronic. Pain persisting longer than three months is chronic. It can result from underlying medical conditions, injury, medical treatment, inflammation, or unknown cause.

The CDC guidelines state that non-pharmacologic and non-invasive methods are the preferred first-line method of analgesia, such as heat/cold therapy, physical therapy, massage, rest, or exercises, etc. Despite evidence supporting their use, these therapies are only sometimes covered by insurance, and access and cost can be barriers, particularly for uninsured persons who have limited resources, no reliable transportation, or live in rural areas where treatments are not available.

When this is insufficient, non-opioid medications, such as Gabapentin, acetaminophen, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID), should be considered next. Selective antidepressants and anticonvulsant medications may also be effective. Some examples of when these drugs may be appropriate include neuropathic pain, lower back pain, musculoskeletal injuries (including minor pain related to fractures, sprains, strains, tendonitis, and bursitis), dental pain, postoperative pain, and kidney stone pain.

Providers, however, must also consider the risks and benefits of long-term NSAID use because it may also negatively affect a patient’s gastrointestinal and cardiovascular system. Depending on the diagnosis, a patient may also require an invasive or surgical intervention to treat the underlying cause to alleviate pain.

If the patient has pain that does not sufficiently improve with these initial therapy regimens, at that point, opioids will be the next option to be considered.

It does not mean that patients should be required to sequentially “fail” nonpharmacologic and non-opioid pharmacologic therapy or use any specific treatment before proceeding to opioid therapy. Example: A patient for whom NSAIDs are contraindicated has recently sustained a rotator cuff injury and is experiencing moderate pain to the point at which it is disturbing their sleep, and it will be several weeks before they can have surgery.

Recommendation #2: Discuss with the patient realistic treatment goals for pain and overall function.

Ideally, goals include improving quality of life and function, including social, emotional, and physical dimensions. The provider should help guide these patients to realistic expectations based on their diagnosis. This may mean that the patient may anticipate reduced pain levels but not complete elimination of pain. The provider should discuss the expected or typical timeframe where they may need medications.

If medications are anticipated for acute or subacute pain, a discussion about the expected timeframe for pain should be highlighted in the debate. The patient may then better understand if their recovery is progressing. For chronic conditions, the conversation will focus on or may emphasize the overall risks of beginning long-term medication therapy. They may also advise patients, particularly those with irreversible impairment injuries, that they may experience reduced pain but will not regain function. A withdrawal plan will be discussed if opioid therapy is unsuccessful or the risk vs. benefit ratio is no longer balanced.

The second section of recommendations covers the selection of opioids and dosages.

Recommendation #3: Prescribe immediate-release (I.R.) opioids instead of extended-release and long-acting (ER/LA) opioids when starting opioid therapy.

Immediate-release opioids have faster-acting medication with a shorter duration of pain-relieving action. ER/LA opioids should only be used in patients who have received specific dosages of immediate-release opioids daily for at least one week. Providers should reserve ER/LA opioids for severe, continuous pain, for example, individuals with cancer. ER/LA opioids should not be for PRN use. The reason for this recommendation is to reduce the risk of overdose. A patient who does not feel adequate relief or relief fast enough from the ER/LA dose may be more inclined to take additional amounts sooner than recommended, leading to a potential overdose.

Recommendation #4: Prescribe the lowest effective dose.

Dosing strategies include prescribing low doses and increasing doses in small increments. Prescribe the lowest dose for opioid patients. Carefully consider risk vs. benefits when increasing amounts for individuals with subacute and chronic pain who have developed tolerance. Providers should continue to optimize non-opioid therapies while continuing opioid therapy. It may include recommendations for taking non-opioid medications in addition to opioids and non-pharmacologic methods.

Providers should use caution and increase the dosage by the smallest practical amount, especially before increasing the total opioid dosage to 50 or greater morphine milligram equivalent (MME) daily. Increases beyond 50 MME/day are less likely to provide additional pain relief benefits. The greater the dosage increases, the tendency for risk also increases. Some states require providers to implement clinical protocols at specific dosage levels.

Recommendation #5: Tapering opioids includes weighing the benefits and risks when changing the opioid dosage.

Providers should consider tapering to a reduced dosage or tapering and discontinuing therapy and discuss these approaches before initiating changes when:

- The patient requests dosage reduction or discontinuation,

- Pain improves and might indicate the resolution of an underlying cause,

- Therapy has not reduced pain or improved function,

- Treated with opioids for a long time (e.g., years), and the benefit-risk balance is not clear.

- Receiving higher opioid dosages without evidence of improvement.

- Side effects that diminish the quality of life or cause impairment.

- Opioid misuse

- The patient experiences an overdose or severe event.

- Receiving medications or having a condition that may increase the risk of an adverse event.

Opioid therapy should not be discontinued abruptly unless there is a threat of a severe event, and providers should not rapidly reduce opioid dosages from higher dosages.