Minnesota RN Renewal Bundle

Contact Hours: 24

Author(s):

- Edith Fomuso MSN, CCM, RN

- Phillip Meredith MSN, RN

- Kayla Cavicchio BSN, RN, CEN

- Elaine Enright RN

- R.E. Hengsterman MSN, RN, MA

- Abbie Schmitt MSN, RN

- Charmaine Robinson MSN-Ed, BSN, RN

- Michael York MSN, RN

- Tabo Mwikisa-Kelly DNP, MSN, RN, CNEcl

- Cathleen Adams CNO, RN CENP

- Madeira Fountaine MSN, RN, PHN

Course Highlights

- In this Minnesota RN Renewal Bundle course, we will learn how to identify and analyze quality improvement opportunities.

- You’ll also learn how to prevent workplace violence towards nurses.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of important stages of the dying process.

Quality Improvement for Nurses

Introduction

Welcome to the world of Quality Improvement (QI) in healthcare, a dedicated field committed to continually enhancing patient care and outcomes. Quality Improvement involves a systematic approach to identifying, analyzing, and addressing areas for improvement within healthcare processes, ultimately resulting in improved patient safety, satisfaction, and overall healthcare excellence (13). In this course, we will embark on a journey to explore the fundamental principles and practical applications of QI, explicitly tailored for nurses who aspire to make a positive impact in their healthcare settings.

As a nurse, you know the significance of providing high-quality patient care. However, you may wonder how you can actively contribute to improving the systems and processes in your workplace.

Imagine this scenario: You observe a recurring issue with medication administration, where doses are occasionally missed due to workflow inefficiencies. Through this course, you will acquire the knowledge and skills to apply QI methodologies like Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles to investigate such issues, implement changes, and monitor the impact of your interventions. By understanding QI principles and tools, you will be better equipped to collaborate with your colleagues, drive meaningful improvements, and ensure that your patients receive the best care possible.

Ask yourself...

- How can nurses leverage their unique position at the bedside to identify opportunities for quality improvement in healthcare settings?

- Can you provide an example from your own experience or knowledge of how a quality improvement project led to tangible improvements in patient care?

- What potential challenges could a nurse encounter when implementing quality improvement projects?

What is Quality Improvement?

Quality Improvement (QI) in healthcare represents an ongoing, systematic effort to elevate the quality of patient care and healthcare services that involves identifying areas needing improvement, implementing changes, and evaluating the effects of those changes to ensure better patient outcomes (12).

Let’s envision a scenario where a hospital’s surgical department grapples with a higher-than-average rate of post-operative infections. Through a QI initiative, the healthcare team can meticulously scrutinize the surgical processes, pinpoint potential sources of infection, and introduce evidence-based practices such as enhanced sterilization techniques or more rigorous antibiotic prophylaxis protocols. Over time, they can gauge the effectiveness of these changes by monitoring infection rates for a reduction.

Commonly used QI methodologies in healthcare include the DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) process and the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle. These approaches provide structured frameworks for healthcare professionals to tackle issues systematically and iteratively. For example, imagine a bustling primary care clinic with extended patient wait times.

Here, the PDSA cycle can come into play using the systematic iterative steps below:

- The team defines the problem (lengthy wait times)

- The team proceeds to test a change (for example, adjusting appointment scheduling)

- The team then scrutinizes the results and acts accordingly to refine the process.

Ask yourself...

- How does the concept of Quality Improvement (QI) align with the goal to provide the best possible care for patients?

- Can you think of a specific healthcare scenario where QI methodologies like DMAIC or PDSA could significantly improve patient care?

- What are the advantages of using structured frameworks like DMAIC and PDSA in QI initiatives?

- How do DMAIC or PDSA contribute to the success of improvement projects?

History and Background

The history and background of Quality Improvement (QI) in healthcare have a rich and evolving timeline, dating back to the early 20th Century, with significant developments occurring over the years. One pivotal moment in this journey was the introduction of statistical quality control by Dr. Walter A. Shewhart in the 1920s (24). Dr. Shewhart’s pioneering work laid the foundation for using statistical methods to monitor and enhance processes, a concept that would become integral to QI initiatives (24).

In the mid-20th Century, Dr. W. Edwards Deming’s contributions further propelled QI principles forward (7). Dr. Deming emphasized the significance of continuous improvement, active employee engagement, and process variability reduction. His ideas found fertile ground in post-World War II Japan, playing a crucial role in the nation’s economic recovery and the emergence of renowned companies like Toyota, famous for its Toyota Production System (TPS), incorporating QI concepts (7).

Until today, QI has become indispensable to healthcare systems worldwide (16). To illustrate, envision a scenario where a hospital grapples with a high readmission rate among heart failure patients. By scrutinizing historical data and implementing evidence-based protocols for post-discharge care, hospitals can effectively lower readmissions, enhance patient outcomes, and potentially evade financial penalties under value-based reimbursement models (16).

Ask yourself...

- How did the work of Dr. Walter A. Shewhart in the early 20th Century contribute to the foundation of QI, and how do statistical methods continue to play a role in healthcare improvement today?

- What fundamental principles were introduced by Dr. W. Edwards Deming, and how did they influence QI practices in healthcare and other industries?

- Can you provide an example of how QI methodologies, inspired by Deming’s principles, have been successfully applied in modern healthcare settings to address specific challenges or improve patient care?

- How has continuous improvement evolved, and why is it considered a cornerstone of QI in healthcare?

Models

At the heart of ongoing transformations in healthcare lie various Quality Improvement (QI) models. These models provide structured frameworks for identifying and addressing areas of improvement within healthcare systems (14). They offer healthcare professionals a systematic approach to instigate meaningful process changes, ultimately resulting in elevated care quality. See some models below.

Model for Improvement

The Model for Improvement is a widely recognized and highly effective framework for Quality Improvement (QI) in healthcare. This is because it empowers healthcare professionals to systematically test and fine-tune their ideas for process improvement, ensuring that changes are grounded in evidence and proven effective (17).

The Model for Improvement offers a structured and systematic approach to identifying, testing, and implementing changes to enhance healthcare processes and ultimately elevate patient outcomes.

Developed by Associates in Process Improvement (API), this model revolves around the iterative “Plan-Do-Study-Act” (PDSA) cycle, which forms the foundational structure of QI initiatives (17). The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle is a systematic approach that guides healthcare teams through quality improvement, and it comprises the four key phases below, each contributing to developing and implementing meaningful changes in healthcare practices (12).

- Plan: In this initial phase, healthcare teams define the specific problem they aim to address, set clear and measurable goals, and craft a comprehensive plan for implementing the proposed change. For instance, if a hospital seeks to reduce patient wait times in the emergency department, the plan may involve adjustments to triage protocols or streamlining documentation processes.

- Do: Once the plan is established, the proposed change is implemented, typically on a small scale or within a controlled or pilot environment. This enables healthcare professionals to assess the feasibility and potential impact of the change without making widespread adjustments.

- Study: The study phase involves rigorous data collection and analysis to evaluate the effects of the change. In our example, the hospital would measure the impact of the new triage protocols on wait times, closely examining whether they have decreased as expected.

- Act: Based on the findings from the study phase, the healthcare team makes informed decisions about the change. They may adopt the change if it has successfully reduced wait times, adapt it further for enhanced effectiveness, or, if necessary, abandon it.

The PDSA cycle’s iterative nature means adjustments can be made, and the cycle repeats until the desired improvement is achieved (12).

Lean Model

The Lean model, initially conceived in the manufacturing sector, has found considerable success and applicability in healthcare as a potent tool for process enhancement and waste reduction (22). At its core, Lean thinking revolves around the principles of efficiency and value optimization because it focuses on refining processes to eliminate wasteful elements while simultaneously delivering care of the highest quality (22).

Healthcare organizations have adopted Lean methodologies to tackle many challenges, from reducing patient wait times to improving inventory management and elevating overall patient satisfaction (22). For instance, when a hospital is challenged with prolonged wait times in its outpatient clinic, it can apply Lean principles to systematically analyze the patient flow, pinpoint bottlenecks, and streamline processes.

This might involve reconfiguring furniture to enhance flow, adjusting appointment scheduling, or implementing standardized work procedures. The ultimate objective is to cultivate a patient-centric, efficient environment that ensures timely access to care while meticulously conserving time and resources.

Another integral aspect of Lean thinking is the unwavering commitment to continuous improvement and the pursuit of perfection through the systematic identification and eradication of various forms of waste (19). The forms of waste are often categorized into seven types: overproduction, waiting, unnecessary transportation, overprocessing, excess inventory, motion, and defects (19). By keenly identifying and addressing these forms of waste, healthcare organizations not only enhance the utilization of resources but also curtail costs and elevate the overall quality of care delivery.

Six Sigma Model

The Six Sigma model is a robust and widely adopted healthcare method for improving processes and reducing mistakes (9). It was first used in manufacturing but is now used in healthcare to make processes more consistent and improve by finding and fixing errors and inefficiencies (9).

An example is when a hospital is concerned about the accuracy of medication dosing for pediatric patients. A Six Sigma team might indicate the problem, gather data on dosing mistakes, and find out why the mistakes happened. The strategy may encompass the implementation of standardized dosing protocols, refining staff training programs, and monitoring the medication administration process to eliminate errors.

Six Sigma uses a framework called DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) to make improvements. This framework utilizes data-driven tools to discern problems, quantify their origins, develop practical solutions, and institute control mechanisms to sustain improvements (11). Through this systematic journey, healthcare organizations position themselves to deliver care of elevated quality, curtail costs, and bolster patient safety.

TeamSTEPPS model

TeamSTEPPS, which stands for Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety, is a teamwork and communication model designed explicitly for healthcare settings (4). Developed by the U.S. Department of Defense and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), TeamSTEPPS focuses on improving patient safety by enhancing team collaboration, communication, and decision-making among healthcare professionals (4).

One key element of TeamSTEPPS is using structured communication techniques to prevent errors and misunderstandings. For instance, during patient handoffs from one healthcare provider to another, TeamSTEPPS emphasizes using a structured tool like SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation) to convey critical information succinctly and accurately. This ensures that essential patient details are noted, reducing the risk of adverse events (18).

In a surgical team scenario, TeamSTEPPS principles can be applied to improve teamwork and communication among surgeons, nurses, and anesthesiologists. The model encourages briefings before procedures to set clear objectives, huddles during surgery to address emerging issues, and debriefings afterward to reflect on the process and identify areas for improvement. By fostering a culture of open communication and mutual respect, TeamSTEPPS contributes to safer, more efficient healthcare delivery (4).

Ask yourself...

- How can healthcare organizations determine which QI model suits their specific challenges or improvement goals?

- How do QI models emphasize data collection and analysis, and why is this critical in healthcare?

- Can you imagine a real-world scenario where the Lean Six Sigma framework can successfully improve healthcare processes and outcomes?

- What are some emerging trends or innovations in QI models and methodologies, and how might they shape the future of healthcare quality improvement?

IOM Six Domains of Patient Care

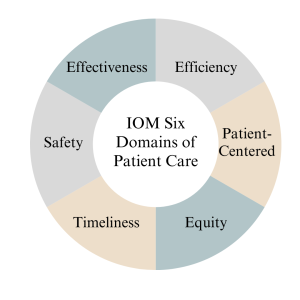

The Institute of Medicine (IOM), now known as the National Academy of Medicine, introduced the Six Domains of Quality in Healthcare as a framework to assess and improve the quality of patient care (14). These domains, introduced in 2001, encompass various aspects of care delivery and patient experience, helping healthcare organizations and providers identify areas for improvement (14). The domains serve as pillars for assessing the different dimensions of care delivery, ensuring that healthcare organizations and providers address the holistic needs of patients (14).

Definitions

The Six Domains of Patient Care are essential for providing high-quality healthcare. Below are definitions of each of the IOM’s six domains of patient care.

Safe: Safety is the foundational domain, emphasizing the importance of reducing the risk of patient harm. This includes preventing medical errors, preventing infections, and ensuring the safe administration of medications. Healthcare organizations implement safety protocols and engage in continuous monitoring to minimize risks (14).

Effective: Effective care ensures that patients receive evidence-based treatments and interventions that result in the desired outcomes. It involves using the best available scientific knowledge to make informed decisions about patient care, avoiding unnecessary or ineffective treatments (14).

Patient-Centered: Patient-centered care focuses on individualizing healthcare to meet each patient’s unique needs and preferences. It involves respecting patients’ values and preferences, engaging them in shared decision-making, and delivering care with empathy and compassion (14).

Timely: Timely care emphasizes reducing delays in healthcare delivery. It includes providing care promptly and avoiding unnecessary waiting times for appointments, tests, and treatments. Timely care is especially critical in emergencies (14).

Efficient: Efficiency in healthcare means maximizing resource utilization and minimizing waste while providing high-quality care. This domain emphasizes streamlining processes, reducing unnecessary costs, and optimizing healthcare resources (14).

Equitable: Equitable care underscores the importance of providing fair and just healthcare, regardless of a patient’s background, socioeconomic status, or other factors. It aims to eliminate healthcare access and outcomes disparities among different patient populations (14).

Measures

Measures in the context of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) six domains of patient care refer to the metrics and indicators used to assess and evaluate the quality of care provided in each domain. According to (14), the measures below are essential for monitoring and improving healthcare services. See details below.

The “Safe” domain tracks and reduces adverse events and medical errors. Key indicators include rates of medication errors, hospital-acquired infections, falls, and procedure complications. Safety measures also assess the implementation of safety protocols, such as hand hygiene compliance and patient identification bracelets.

Measures in the “Effective” domain assess how evidence-based practices and treatments are utilized. These measures include adherence to clinical guidelines, appropriate use of medications, and the success rates of medical interventions. Additionally, outcomes such as patient recovery, remission, or improvement are indicators of the effectiveness of care.

The “Patient-Centered” domain focuses on assessing the patient’s experience and satisfaction with care. Patient surveys and feedback are standard measures, evaluating aspects like communication with healthcare providers, involvement in decision-making, and overall satisfaction with the care received. Healthcare organizations also measure shared decision-making and respect for patient preferences.

Measures related to the “Timely” domain evaluate the efficiency of healthcare delivery. Key metrics include waiting times for appointments, diagnostic tests, and procedures. Additionally, measures track the timely delivery of urgent care and the avoidance of unnecessary treatment delays.

Efficiency measures aim to quantify resource utilization and reduce waste in healthcare. Metrics may include the cost of care per patient, length of hospital stays, and resource allocation efficiency. Improvement in resource utilization and cost-effectiveness is a vital indicator of efficiency.

Measures within the “Equitable” domain assess disparities in healthcare access and outcomes among different patient populations. Healthcare utilization and outcomes data are stratified by demographics, socioeconomic status, race, and ethnicity to identify and address inequities. Key indicators include access to preventive care, healthcare utilization rates, and health outcomes across various demographic groups.

Ask yourself...

- How can healthcare providers ensure their care aligns with patients’ values, preferences, and cultural backgrounds?

- What challenges might patients face in accessing healthcare services, and how can healthcare organizations improve access for all patients?

- What are the potential consequences of poor care coordination among healthcare providers, and how can interdisciplinary teams work together to enhance coordination?

- Why must healthcare organizations continually assess and improve the quality of care they provide, and what mechanisms can be implemented to support ongoing improvement efforts?

Nursing Quality Indicators

According to (5), nursing quality indicators are essential metrics used to evaluate and improve the quality of nursing care in healthcare settings. These indicators provide valuable insights into nursing practice and patient outcomes, helping healthcare organizations and nursing staff deliver safe, effective, patient-centered care. Let’s delve into some key nursing quality indicators and their significance below.

Patient Falls

Patient falls are a critical quality indicator in nursing care since they can result in severe injuries and complications for patients (5). As a result, healthcare organizations measure and monitor the rate of patient falls to identify trends and implement preventive measures.

For example, when a hospital notices an increase in the rate of falls among elderly patients in a particular unit, it may introduce fall prevention strategies such as nonslip flooring, improved lighting, and patient education.

Medication Administration Errors

Ensuring accurate medication administration is crucial in nursing practice because medication errors can lead to adverse events, including patient harm or death (5). Nursing quality indicators related to medication administration errors include the rate of medication errors and adherence to medication reconciliation processes (5). For instance, nurses are encouraged to verify patient allergies and cross-check medication orders to prevent mistakes. If there is an increase in medication errors in a healthcare facility, it may prompt a review of medication administration protocols and additional staff training.

Pressure Ulcers (Bedsores)

Pressure ulcers are a quality indicator of patient skin integrity since they develop when patients remain immobile for extended periods (5). As a result, healthcare organizations measure the incidence and prevalence of pressure ulcers as an indicator of the quality of nursing care (5).

Patient Satisfaction

Patient satisfaction is a patient-centered nursing quality indicator since it reflects the overall patient experience and perception of care (5). Surveys and feedback mechanisms are used to measure patient satisfaction. For example, a scenario might involve patients receiving post-discharge surveys that assess various aspects of their hospital experience, including nurse responsiveness, communication, and pain management. Healthcare organizations can use this feedback to identify areas for improvement and enhance patient-centered care.

In summary, nursing quality indicators encompass a range of metrics that evaluate nursing care quality, patient safety, and patient experiences. By monitoring and responding to these indicators, healthcare organizations and nursing staff can continuously improve their quality of care, leading to better outcomes and increased patient satisfaction (5)

Ask yourself...

- Why is data collection critical in nursing quality improvement efforts?

- What types of data should nurses prioritize collecting to assess patient safety?

- How can nurses ensure the accuracy and reliability of the data they collect for quality improvement purposes?

- What challenges might nurses face when collecting patient-related data, and how can these challenges be overcome?

Data Collection

Quality improvement data collection is a critical component of healthcare quality initiatives. It provides the necessary information to assess the current state of care, identify areas for improvement, and monitor progress over time (2). Accurate and meaningful data collection enables healthcare organizations to make informed decisions, implement evidence-based interventions, and ultimately enhance patient outcomes. Let’s explore the methods of data collection below.

- Clinical Outcome Collection:

- Clinical outcome data collection is essential for assessing the effectiveness of healthcare interventions (2). For example, consider a scenario where a hospital is implementing a quality improvement project to reduce surgical site infections (SSIs) following orthopedic surgeries. Data collection would involve tracking the number of SSIs occurring over a specific period and collecting information on patient characteristics, surgical techniques, and post-operative care protocols. By analyzing this data, the healthcare team can identify trends, risk factors, and areas for improvement, ultimately leading to targeted interventions to reduce SSIs.

- Patient Satisfaction Survey Data Collection:

- Patient satisfaction surveys are valuable tools for collecting data on patient experience (2). A primary care clinic that aims to improve patient satisfaction may administer surveys to patients after each visit, asking about aspects of care such as communication with healthcare providers, wait times, and overall experience. The collected data can reveal areas of strength and areas requiring improvement. For instance, if survey results consistently indicate longer-than-desired wait times, the clinic can adjust scheduling practices or implement strategies to reduce wait times and enhance patient satisfaction.

- Process Measures Data Collection:

- Process measure data collection focuses on evaluating the efficiency and effectiveness of healthcare processes (2). For instance, in a medication reconciliation scenario, a healthcare organization might collect data on the accuracy and completeness of medication lists during care transitions. By tracking the frequency of medication reconciliation discrepancies, they can identify process inefficiencies and implement standardized protocols for reconciliation, leading to safer care transitions and reduced medication errors.

- Adverse Event Reporting Data Collection:

- Adverse event reporting is a crucial mechanism for collecting data on incidents that result in patient harm or near misses (2). Consider a scenario where a nurse administers the wrong medication dose to a patient but catches the error before any harm occurs. Reporting this near-miss event allows the healthcare organization to investigate the root causes, implement preventive measures, and share lessons learned with the care team to prevent similar incidents in the future.

Types of Data

Data types play a crucial role in understanding the current state of care, identifying areas for improvement, and implementing evidence-based interventions (2). Let’s explore the different types of data used in quality improvement below.

- Quantitative Data:

- Quantitative data involves numerical measurements and is particularly useful for assessing the frequency and extent of specific events or outcomes (2). For instance, in a hospital’s quality improvement project focused on reducing hospital-acquired infections, the team collects quantitative data on the number of infections over time, allowing them to track trends and measure the impact of interventions, such as hand hygiene protocols or disinfection practices.

- Qualitative Data:

- Qualitative data provides insights into the “why” and “how” behind healthcare processes and patient experiences (2). This data type is collected through interviews, focus groups, and open-ended surveys. For example, in a primary care setting aiming to improve patient satisfaction, patient interviews may be conducted to gather in-depth information about their perceptions of care. Qualitative data can uncover nuances and provide valuable context to complement quantitative findings (2).

- Patient-Reported Data:

- Patient-reported data includes information directly provided by patients about their health, symptoms, experiences, and preferences. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and patient-reported experience measures (PREMs) are standard data collection tools. In a scenario involving chronic disease management, patients with diabetes may be asked to complete a PROM assessing their quality of life and symptom management. This data helps healthcare providers tailor care plans to individual patient needs and preferences (2).

- Process Data:

- Process data is used to track the steps and activities involved in healthcare delivery and to help assess the efficiency and effectiveness of care processes. For example, in a surgical quality improvement initiative, process data may include the time from patient admission to surgery, completion of the surgical team checklist, and adherence to anesthesia protocols. By collecting and analyzing process data, healthcare organizations can identify bottlenecks and areas for improvement in care delivery processes.

In summary, quality improvement data collection relies on various data types, including quantitative, qualitative, patient-reported, and processed data. Each data type contributes to a comprehensive understanding of healthcare quality and supports evidence-based decision-making to enhance patient care and outcomes.

Identification Stage

The identification stage for quality improvement data collection is a critical initial phase where healthcare organizations and teams define what data to collect, why it is relevant, and how it aligns with their quality improvement goals (23). This stage is essential for ensuring that meaningful data collection efforts lead to actionable insights. Let’s explore the identification stage in more detail.

- Defining Objectives and Goals:

- During this stage, healthcare organizations must clearly define the objectives and goals of their quality improvement initiative (23). For instance, a hospital aiming to reduce readmission rates for heart failure patients may set a specific goal of reducing readmissions by 20% within the following year.

- Selecting Relevant Metrics:

- Identifying the right metrics and data points is crucial, and organizations should choose metrics that directly relate to their quality improvement goals (23). Continuing with the example of reducing heart failure readmissions, relevant metrics might include the number of heart failure patients readmitted within 30 days, the reasons for readmission, and patient characteristics. By selecting these metrics, the organization ensures that data collection efforts are aligned with its specific improvement goal.

- Determining Data Sources:

- Healthcare organizations must identify where the necessary data will be sourced (23). This may involve looking at electronic health records, claims data, patient surveys, or other sources. For instance, to collect data on heart failure readmissions, the hospital may extract relevant information from electronic health records, including admission and discharge dates, diagnosis codes, and patient demographics.

- Creating Data Collection Protocols:

- Establishing clear data collection protocols is essential for consistency and reliability (23). Healthcare teams should define how data will be collected, who will be responsible for data collection, and the frequency of data collection. For example, in a hospital project aiming to improve hand hygiene compliance, data collection protocols might specify that trained observers will monitor hand hygiene practices at random intervals and record their findings on standardized forms.

By carefully navigating the identification stage, healthcare organizations ensure that their quality improvement data collection efforts are purposeful and aligned with their goals. This sets the stage for collecting meaningful data to drive evidence-based decisions and interventions to enhance healthcare quality.

Gathering Stage

The gathering stage of quality improvement data collection is crucial for healthcare organizations to collect the identified data based on their quality improvement objectives and goals (23). This stage involves systematically collecting data from various sources and often requires careful planning and coordination to ensure data accuracy and completeness. Let’s delve into the gathering stage in detail below.

- Data Collection Methods:

- To gather data, healthcare organizations must determine the most suitable methods for collecting the identified data, which may involve a combination of electronic health records, patient surveys, direct observations, and administrative databases (23). For example, in a quality improvement project aimed at reducing hospital readmissions, data may be collected by reviewing electronic health records to track patient outcomes, conducting patient surveys to gather feedback on discharge instructions, and analyzing administrative data to identify trends in readmission rates.

- Ensuring Data Accuracy and Consistency:

- Data accuracy is critical in the gathering stage, and organizations must implement procedures to collect data consistently and without errors (23). For instance, if a healthcare facility is collecting data on medication administration, nurses may use standardized protocols to record medication administration times and doses accurately. Regular training and quality checks may also be implemented to maintain data accuracy.

- Timely Data Collection:

- Timeliness is another important aspect of the gathering stage, and data should be collected promptly to ensure it is current and relevant for analysis and decision-making (23). In a scenario involving tracking patient outcomes, healthcare teams may set specific intervals for data collection, such as collecting post-surgical complication data daily or weekly, depending on the project’s requirements.

- Data Security and Privacy:

- Protecting patient data is a paramount concern in healthcare. As a result, healthcare organizations must adhere to strict privacy and security protocols during the gathering stage to ensure that patient information is handled confidentially and complies with applicable laws and regulations, such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) (23). For example, when collecting patient-reported data, organizations may anonymize responses to protect patient identities and comply with privacy regulations.

By effectively managing the gathering stage, healthcare organizations can ensure that they collect accurate, timely, and secure data that will serve as the foundation for subsequent analysis and quality improvement efforts.

Analysis Stage

The analysis stage for quality improvement data collection is a critical phase where collected data is processed, examined, and transformed into actionable insights. This stage involves various analytical techniques and tools to identify patterns, trends, and areas for improvement (2). Let’s explore the analysis stage in detail below.

- Descriptive Analysis:

- Descriptive analysis is the initial step in data analysis, focusing on summarizing and presenting data meaningfully (2). For example, in a quality improvement project aimed at reducing patient wait times in an emergency department, an analysis may involve calculating and displaying key statistics, such as average wait times, 95th percentile wait times, and the distribution of wait times (2). These descriptive statistics provide an overview of the current situation and help identify areas that need attention.

- Root Cause Analysis (RCA):

- Root cause analysis is a critical aspect of the analysis stage, as it helps pinpoint the underlying causes of issues or problems (2). In our scenario, if the analysis reveals prolonged wait times in the emergency department, RCA may involve a thorough investigation into the factors contributing to the delays. Potential root causes include staffing shortages, inefficient triage processes, or bottlenecks in diagnostic testing. Identifying these root causes is essential for developing effective interventions.

- Statistical Analysis:

- Statistical analysis plays a vital role in quality improvement by examining the relationships between variables and testing hypotheses (2). In reducing hospital readmissions, statistical analysis may be used to identify factors associated with readmission risk. For example, healthcare teams can use logistic regression to analyze patient data to determine which variables, such as comorbidities or medication adherence, are statistically significant predictors of readmission risk. This information can guide the development of targeted interventions for at-risk patients.

- Benchmarking:

- Benchmarking involves comparing an organization’s performance data with industry standards or best practices to identify performance gaps (2). When a hospital is looking to improve patient satisfaction, benchmarking may involve comparing its patient satisfaction scores to those of similar hospitals or national averages. Identifying areas where the hospital falls behind benchmarks can inform strategies for improvement, such as implementing best practices from higher-performing institutions.

The analysis stage is critical for transforming raw data into actionable insights and understanding healthcare quality factors (2). Through descriptive analysis, root cause analysis, statistical techniques, and benchmarking, healthcare organizations can gain valuable insights that drive evidence-based decisions and interventions to improve care quality (6).

Benchmarking

The benchmarking stage in quality improvement data collection is a crucial phase where healthcare organizations compare their performance against established benchmarks or best practices (1). This gives healthcare organizations a clear understanding of their position relative to recognized standards and allows them to effectively identify areas for improvement, prioritize, and focus their improvement efforts (5). Let’s delve into the benchmarking stage in detail below.

Defining Benchmarks:

In the benchmarking stage, healthcare organizations must define the benchmarks or standards against which they will measure their performance. These benchmarks can be internal (comparing current performance to historical data) or external (comparing to industry standards, best practices, or similar organizations) (1). For example, a primary care clinic seeking to improve appointment scheduling efficiency may choose to benchmark its appointment wait times against industry benchmarks for acceptable wait times.

- Collecting Comparative Data:

- Gathering data that allows for a meaningful comparison is critical in benchmarking, so healthcare organizations must collect data from relevant sources to measure their performance against the chosen benchmarks (1). Continuing with the appointment scheduling example, the clinic may collect data on the time it takes to schedule an appointment, the number of scheduling errors, and patient feedback. This data is then compared to industry benchmarks or best practices.

- Identifying Performance Gaps:

- The benchmarking process reveals gaps or disparities between an organization’s performance and the benchmarks to highlight improvement areas (1). For instance, if the clinic discovers that its appointment wait times are significantly longer than industry benchmarks, this identifies a performance gap that needs to be addressed to enhance patient access and satisfaction.

- Developing Improvement Strategies:

- Once performance gaps are identified, healthcare organizations can develop targeted improvement strategies. These strategies are based on evidence from the benchmarking process and aim to align performance with or exceed established benchmarks (1). In our scenario, the clinic may implement strategies such as optimizing appointment scheduling processes, enhancing staff training, or using technology to improve scheduling efficiency.

Ask yourself...

- Why is data collection a crucial step in the quality improvement process?

- What types of data are typically collected during the data collection stage of quality improvement?

- How do you determine which data points are relevant to your quality improvement project?

- What methods and tools can be used to collect data accurately and efficiently?

Change Models in Healthcare

Change models are essential frameworks used in healthcare, including nursing, to guide and manage the effective implementation of quality improvement initiatives (15). These models offer structured approaches to initiating, planning, executing, and sustaining changes in healthcare practice (15). Let’s discuss some prominent change models used in nursing quality improvement below.

- Kotter’s 8-Step Change Model:

- Developed by Dr. John Kotter, this model emphasizes the importance of creating a sense of urgency, building a guiding coalition, and sustaining the change (15). For instance, in a nursing scenario focused on reducing hospital-acquired infections, the 8-step model would involve creating urgency by highlighting the impact of infections on patient safety, assembling a coalition of nurses and infection control specialists, and sustaining change by monitoring infection rates over time and continually reinforcing hygiene protocols.

- Lewin’s Change Management Model:

- Lewin’s model consists of three stages: unfreezing, changing, and refreezing (15). Consider implementing a new electronic health record (EHR) system in nursing. Nurses first “unfreeze” by acknowledging the need for a new system and undergoing training. Then, they “change” by adopting the EHR and adjusting workflows. Finally, they “refreeze” by becoming proficient and maintaining the new system’s use as a standard practice.

- PDSA Cycle (Plan-Do-Study-Act):

- This model emphasizes iterative cycles of planning, implementing, observing, and adjusting (15). For instance, if a nursing unit aims to improve patient handoffs, they might “plan” by identifying handoff best practices, “do” by implementing changes, “study” by assessing the impact on patient outcomes, and “act” by making further refinements based on their findings. This continuous cycle allows for gradual, data-driven improvements.

- ADKAR Model:

- The ADKAR model focuses on individual change management, which could apply to a scenario where nurses adopt new pain management protocols (15). Nurses would first need awareness of the change (A), followed by desire (D) to participate, knowledge (K) of how to implement the new protocols, ability (A) to do so, and reinforcement (R) to sustain the change over time.

In summary, change models provide structured approaches to driving quality improvement initiatives in nursing. By applying these models, nurses and healthcare organizations can systematically plan, implement, and evaluate changes to enhance patient care, safety, and outcomes (15).

Ask yourself...

- Why are change models essential in nursing quality improvement initiatives?

- What is the primary purpose of creating a sense of urgency in change models like Kotter’s 8-Step model?

- How does Lewin’s Change Management Model address the need to “unfreeze” existing practices in nursing before implementing change?

- Why is individual change management crucial in nursing practice, as the ADKAR model emphasizes?

Implementing Change

Implementing changes for quality improvement in nursing is a multifaceted process that requires careful planning, effective communication, and the engagement of healthcare professionals at all levels. According to (15), successful implementation ensures that desired changes are integrated into daily nursing practice, improving patient outcomes. Let’s explore key strategies and considerations for implementing changes in nursing quality improvement below.

- Engage Interdisciplinary Teams:

- According to (15), collaborative engagement is crucial when implementing changes in nursing practice, and healthcare organizations should assemble interdisciplinary teams that include nurses, physicians, administrators, and other stakeholders. For example, in a scenario involving the adoption of a new pain management protocol, nurses can collaborate with physicians to ensure the consistent application of evidence-based pain management practices. This team approach facilitates a shared understanding of the change and fosters buy-in from all parties.

- Effective Communication:

- Clear and consistent communication is essential during the implementation phase, so nurses should communicate the rationale behind the change, its expected benefits, and the specific steps involved (15). For example, suppose a hospital is transitioning to a new electronic health record system. In that case, nurses can attend training sessions to understand its features and communicate effectively with patients about how it will enhance their care. This ensures that all stakeholders are informed and can adapt to the change seamlessly.

- Training and Education:

- Adequate training and education are critical to equipping nursing staff with the knowledge and skills to implement change effectively (15). For example, introducing a new wound care protocol would require nurses to be trained on the updated practices, wound assessment techniques, and the use of new wound care products. In addition to initial training, ongoing education would ensure that nursing staff stay current with best practices to provide quality care confidently.

- Continuous Monitoring and Feedback:

- According to (15), implementing change is an ongoing process that requires constant monitoring and feedback since feedback mechanisms allow for adjustments and refinements to the change process. As a result, nursing quality improvement initiatives benefit from the regular collection and analysis of data to assess the impact of the change. For example, suppose a hospital introduces a sepsis screening tool. In that case, nurses can track the number of patients screened, identify missed cases, and evaluate whether early interventions have reduced sepsis-related mortality rates.

By engaging interdisciplinary teams, fostering effective communication, providing training and education, and implementing continuous monitoring and feedback mechanisms, nurses can successfully implement changes that improve the quality of patient care and enhance overall healthcare outcomes (8).

Ask yourself...

- Why is it crucial for nursing teams to engage in interdisciplinary collaboration when implementing changes for quality improvement?

- How can effective communication strategies help nursing staff understand the purpose and benefits of a proposed change in healthcare practice?

- What role does ongoing training and education play in ensuring that nursing staff are well-prepared to implement and sustain changes in their practice?

- What methods can be employed to gather feedback from nursing staff while implementing a new practice or protocol?

Evaluating Change

Evaluating change for quality improvement in nursing is a critical phase that involves assessing the impact and effectiveness of implemented changes on patient care outcomes, safety, and the overall quality of healthcare services. According to (15), rigorous evaluation ensures that improvements are sustained and necessary adjustments are made. Let’s explore key strategies and considerations for evaluating changes in nursing quality improvement below.

- Establishing Clear Evaluation Metrics:

- To evaluate change effectively, it is essential to define clear and measurable evaluation metrics, and according to (15), these metrics should align with the specific objectives of the change initiative. For example, suppose a nursing unit has introduced a new hand hygiene protocol to reduce hospital-acquired infections. In that case, evaluation metrics may include the number of infections before and after the change, adherence to hand hygiene guidelines, and patient satisfaction scores related to cleanliness and infection prevention.

- Data Collection and Analysis:

- Data collection is a fundamental component of the evaluation process, and nursing teams should collect relevant data using standardized methods and tools (15). In our scenario, data on infection rates can be collected regularly, and statistical analysis can be performed to determine whether the change has had a statistically significant impact. Nurses can then use run charts or control charts to visualize trends in infection rates over time, allowing for early detection of any potential issues.

- Patient and Staff Feedback:

- Patient and nursing staff feedback is invaluable in evaluating change. Patients’ perspectives on the quality of care and their experiences following the change can provide insights into the initiative’s effectiveness (15). Additionally, nursing staff can provide feedback on the practicality and feasibility of the new practices. For instance, nursing staff may suggest further improvements in infection control procedures.

- Sustainability and Continuous Improvement:

- Evaluating change is not solely about assessing immediate outcomes but also ensuring sustainability and continuous improvement. According to (15), nursing teams should determine whether the positive effects of the change are maintained over time and whether there is room for further refinement. For example, when a nursing unit has reduced infection rates, regular audits and monitoring should continue to ensure sustained compliance with hygiene protocols.

Ask yourself...

- Why must nursing teams establish clear and measurable evaluation metrics when assessing the impact of change in healthcare practice?

- How can nurses effectively collect and analyze data to evaluate the success of a change in their nursing practice?

- What role does patient feedback play in evaluating the impact of a change on the quality of nursing care, and how can this feedback be gathered and utilized?

- How can nursing staff engage in ongoing self-assessment to determine their practice changes’ effectiveness and identify improvement areas?

- What specific infection prevention measures should nurses prioritize in their daily practice to reduce hospital-acquired infections, and why are these measures effective?

- What are the primary goals of a quality improvement project to reduce hospital-acquired infections, and how can nursing staff contribute to achieving these goals?

- Why is continuous monitoring and evaluation crucial in quality improvement projects, and how can nursing staff use data to drive ongoing improvements in patient care quality?

Enhancing Medication Safety

Medication errors can have severe consequences for patients (6). A quality improvement project may target medication safety by introducing barcode scanning systems for medication administration, implementing double-check procedures for high-risk medications, and providing ongoing training to nursing staff. The project’s effectiveness can be assessed by monitoring the number of medication errors reported and verifying that the new safety measures reduce the occurrence of such errors. For example, a nursing team could reduce the incidence of wrong-patient medication administration by implementing barcode scanning during medication administration.

Ask yourself...

- How can nurses ensure that barcode scanning systems and double-check procedures are effectively integrated into their daily workflow in medication safety improvement projects?

- What potential challenges and barriers can nurse units encounter when implementing medication safety improvements, and how can these challenges be addressed?

Improving Nurse-to-Patient Ratios

Adequate nurse staffing levels are crucial for patient safety and quality of care (6). A quality improvement project may involve adjusting nurse-to-patient ratios based on patient acuity levels, introducing workload management tools, and conducting regular staffing needs assessments. In this case, the project’s success can be measured by tracking patient outcomes, nurse workload, and patient satisfaction scores. For example, a nursing unit could reduce nurse burnout and improve patient care by optimizing staffing ratios during peak hours.

Ask yourself...

- Why is it important to regularly assess and adjust nurse-to-patient ratios in a healthcare setting, and what strategies can nurse leaders employ to optimize staffing levels?

- In a quality improvement project focused on nurse-to-patient ratios, what key factors should nurse leaders consider when determining staffing needs during different shifts and patient acuity levels?

Enhancing Discharge Planning and Care Transitions

Effective care transitions from the hospital to home or other healthcare settings are essential to preventing readmissions and ensuring continuity of care (6). A quality improvement project may focus on improving the discharge planning process, including patient education, medication reconciliation, and post-discharge follow-up. Success can be assessed by monitoring readmission rates and patient-reported experiences. For example, a nursing team could work on reducing hospital readmissions by ensuring that patients receive thorough discharge instructions and have access to follow-up care.

Ask yourself...

- What steps can nurse teams take to enhance the discharge planning process and ensure seamless care transitions for patients moving from the hospital to home care?

- What strategies can nurse teams employ to ensure that patient education during discharge planning is effective and leads to better patient outcomes and satisfaction?

- Why is continuous monitoring and evaluation crucial in quality improvement projects, and how can nursing staff use data to drive ongoing improvements in patient care quality?

- What are the primary goals and objectives of QI models, and how do they contribute to the overall quality of healthcare?

Conclusion

In conclusion, this course provides essential knowledge and skills valuable for nurses aiming to deliver high-quality, safe, patient-centered care. Quality improvement in nursing is not merely a theoretical concept but a practical approach that can be applied to various aspects of healthcare, and one critical aspect to remember is the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration. As frontline caregivers, nurses must collaborate with physicians, administrators, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals to drive improvements in healthcare delivery. The above examples illustrate the diverse range of quality improvement projects in nursing, each addressing specific challenges to enhance patient safety and care quality.

As nurses continue to play a pivotal role in healthcare delivery, the knowledge and skills gained from this course will empower them to lead and actively participate in quality improvement initiatives. By applying quality improvement principles, nurses can contribute to better patient experiences, patient outcomes, and overall healthcare quality.

Ask yourself...

- What have you learned from this course?

- Why is interdisciplinary collaboration essential for nurses to effectively implement quality improvement initiatives in healthcare settings, and how can nurses foster collaboration among healthcare professionals?

- How does the concept of continuous learning and adaptation align with the dynamic nature of healthcare, and what strategies can nurses employ to stay current with evolving best practices and guidelines?

- In what ways does Quality Improvement benefit both healthcare providers and patients?

- What are the potential challenges in implementing QI initiatives in a healthcare organization?

- In what ways has QI in healthcare become intertwined with the broader goals of healthcare reform, such as improving patient outcomes and reducing healthcare costs?

- What role does leadership play in the effective implementation of QI models?

- How can leaders promote a culture of continuous improvement within healthcare organizations?

- How do QI models facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration among healthcare professionals to drive improvements in patient care?

- What challenges might healthcare organizations face when attempting to adopt and sustain QI models, and how can these challenges be overcome?

- How does the “testing and learning” concept in the PDSA cycle align with the principles of evidence-based practice in healthcare?

- In what ways do QI models promote patient-centered care and patient safety, and can you provide examples of tangible improvements in these areas achieved through QI initiatives?

- How can the Six Sigma model contribute to the reliability and consistency of healthcare processes?

- Safe: What steps can healthcare organizations take to minimize the risk of medical errors and adverse events?

- Practical: How do healthcare providers ensure that evidence-based treatments and interventions lead to positive patient outcomes?

- Patient-centered: Why is it important to involve patients in their care decisions, and how can healthcare professionals effectively engage patients in the decision-making process?

- Timely: What are some key factors contributing to delays in healthcare delivery, and how can these delays be reduced to improve timeliness?

- Efficient: How can healthcare processes and workflows be streamlined to enhance efficiency and reduce waste?

- Equitable: What are some barriers to achieving healthcare equity, and how can healthcare organizations address these disparities?

- How can nurses actively involve patients in data collection to enhance patient-centered care?

- What tools or technologies are available to streamline data collection processes in nursing practice?

- How can nurses effectively collaborate with interdisciplinary teams to gather comprehensive data for quality improvement initiatives?

- What strategies can nurses employ to maintain patient privacy and confidentiality while collecting sensitive healthcare data?

- What methods can nurse use to analyze and interpret the data they collect to identify areas for improvement?

- Why must nurses regularly review and assess the data they collect to drive continuous quality improvement in healthcare settings?

- Regarding patient falls, what strategies can healthcare organizations implement to reduce the incidence of patient falls, and how can nursing staff actively contribute to fall prevention efforts?

- How can nurses ensure the accurate and safe administration of medications, and what measures can be taken to minimize medication errors?

- What are the key nursing practices and interventions that can prevent the development of pressure ulcers in hospitalized patients, and how can nursing staff collaborate to achieve this goal?

- Why is patient satisfaction an important nursing quality indicator, and what actions can nurses take to enhance the overall patient experience?

- What impact do nurse-to-patient staffing ratios have on the quality of nursing care, and how can healthcare organizations ensure safe nurse staffing levels?

- How can nurses enhance patient education to promote better understanding and self-management of their health conditions?

- How can you ensure that the data collected is reliable and valid?

- What role does standardization play in data collection for quality improvement?

- How can you establish baseline data for comparison in your quality improvement project?

- What challenges or obstacles might you encounter when collecting data for quality improvement?

- How frequently should data be collected to monitor progress in a quality improvement project?

- How can you involve frontline staff in the data collection to ensure accuracy?

- What measures can be taken to protect patient privacy and confidentiality during data collection?

- How can you analyze the data collected to identify trends or patterns?

- What actions should be taken if the data collected indicates a problem or deviation from the desired outcome?

- What strategies can ensure that data collection remains an ongoing and sustainable practice in healthcare quality improvement efforts?

- What are the potential challenges or resistance nurses might encounter when implementing changes using these models?

- How can a guiding coalition or interdisciplinary team be effectively assembled to support nursing quality improvement efforts?

- What strategies can nurses employ to sustain changes and prevent reverting to previous practices once implemented?

- How can nursing leaders ensure that staff have the necessary knowledge and skills to embrace the changes outlined in these models?

- How can nurses use these change models to promote a culture of continuous improvement in healthcare settings?

- How can nurses ensure their implementation changes align with evidence-based best practices and clinical guidelines?

- What potential challenges or barriers might nurse teams encounter when trying to implement changes for quality improvement?

- What strategies can address resistance to change among nursing staff and promote their active participation in the implementation process?

- How can nursing leaders effectively communicate the expected outcomes and benefits of the change to gain support and commitment from their teams?

- What are the advantages of using data and performance metrics to monitor the progress and impact of change implementation in nursing practice?

- How can nursing staff ensure that changes are sustained and become integral to their daily practice rather than temporary modifications?

- Why is it crucial to consider the sustainability of change when evaluating its long-term impact on nursing quality improvement?

- What challenges or obstacles might nurse teams encounter when collecting and analyzing data for change evaluation, and how can these challenges be addressed?

- How can nursing leaders encourage a culture of continuous improvement among their teams as part of the change evaluation process?

- What strategies can be employed to ensure that the feedback and insights gathered during the evaluation phase are actively used to refine and optimize nursing practices?

- What are the potential consequences of not conducting thorough and systematic evaluations of changes in nursing practice for quality improvement?

- How can nursing staff and healthcare organizations ensure that the lessons learned from change evaluations are applied to future improvement initiatives to enhance patient care outcomes?

Workplace Violence Against Nurses

Introduction

The role of the registered nurse, while fundamentally dedicated to the care and well-being of patients, has long been fraught with challenges that extend beyond the complexities of medical care. One such pressing concern is workplace violence, an issue that nurses confront with alarming frequency. Recent statistics show that healthcare workers, particularly nurses, are at a higher risk of workplace violence compared to other professions.

Given nurses’ vital role in patient care and the broader healthcare system, it is imperative to understand the scope, sources, and solutions to this pressing issue. This continuing education course is dedicated to arming nurses with the knowledge, tools, and strategies to recognize, respond to, and prevent incidents of workplace violence, thereby ensuring their safety and the uninterrupted provision of quality care.

Definitions

The Occupational and Safety Health Administration (OSHA) (3) defines workplace violence (WPV for the purpose of this course) as any act or threat of physical violence, harassment, intimidation, or other threatening, disruptive behavior that occurs at the work site. This can also include verbal, written, or acts of sabotage against an individual while they are at work.

Workplace violence crosses all demographic barriers and is indiscriminate in who it can and does affect. Seeing workplace violence influences morale, attendance, and the overall well-being of employees and their co-workers.

Types of Violence

Currently, there are four categories of workplace violence according to the American Nurses Association (5).

- Criminal Intent – typically involves theft from the business or employees.

- Example: Carol is working on documentation and notices a person lingering in the hallway. Carol doesn’t really think anything of it, assuming they are family members of one of the patients. Several minutes later, the person exits quickly from the supply room and down the stairs. Carol calls security to inform them, but they can’t locate the individual. After looking through the supply room, they found several missing wound dressing supplies.

- Customer/client/patient – the individual becomes violent with employees while receiving services.

- Example: David was updating a family on their father’s critical condition. David could tell the family was upset, but the patient’s son seemed more frustrated than the others. During David’s explanation, the son grabbed David’s clipboard and yelled, “You’re not doing anything! You’re just letting him die!” The son then threw the clipboard at David’s head. David blocked the clipboard with his arm, receiving a relatively deep cut. Security became involved, and David had to go to the ER for treatment.

- Worker on worker – an employee bullies, attacks, or threatens another employee.

- Example: Emily was rounding when Dr. G. came onto the floor. This doctor was well known for being difficult to work with, and he always required the nurses to stand behind him in the room while he talked with his patients. Emily had one of Dr. G.’s patients today, and was in the room; he asked her if the patient had ambulated. Emily told him they had not, but they planned to before and after lunch. The doctor made an audible sigh and, while shaking his head at the patient, said, “See…this is what I deal with every day. These nurses can’t get anything right. They’re all useless.”

- Personal relationship: This involves a person who has an interpersonal relationship with the nurse but no association with the nurse’s employer or the business.

- Example: Rebecca was walking to her car after work. Halfway to her car, she noticed an individual leaning against the trunk of her vehicle. Rebecca recognized this person as someone her friend was currently dating. This person approached Rebecca aggressively, yelling about gossiping and trying to break their relationship. Rebecca started back toward the building, hoping security was nearby, and was pursued by the female. Eventually, Rebecca made it to the building and got inside. Luckily, the door only opened with an employee badge, and Rebecca was safe. She went ahead to security.

Currently, the customer/client type of workplace violence is the most prominent, especially in healthcare and toward nurses. The American Nurses Association (ANA) reports that OSHA does not require employers to implement workplace violence prevention programs. Still, it supplies voluntary guidelines and may cite employers for not delivering a workplace without recognized serious hazards.

Some states have legislated that employers develop a program. In contrast, most states have advanced laws that amend existing statutes for assaults on first responders by adding health care providers/nurses and/or increasing the penalty associated with such behavior. (3)

It is worth noting that, since there are, in most cases, no actual requirements for employers to provide safe work environments for nurses, preventing and dealing with WPV proves problematic. It falls on nurses to understand what constitutes WPV, how to manage it, how to cope with it, how to report it, and how to ensure action is taken and a resolution is reached when WPV occurs.

Ask yourself...

- In the scenarios above, should the employees report these incidents to administration at once?

- How would you describe the earlier scenarios on workplace violence?

- Why is it important to ask how you would find and describe workplace violence?

- Can you provide any examples of workplace violence you have experienced or seen?

Epidemiology

Workplace violence can take many forms, and the possible varieties and scenarios are endless. Regardless of how it manifests, the effects of workplace violence are clear and widespread. It can affect productivity of employees, morale, attendance, turnover rates, quality of work, patient outcomes, and much more.

Workplace violence can affect and involve workers, clients, customers, and visitors. WPV ranges from threats and verbal abuse to physical assaults and even homicide. In 2010, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data reported healthcare and social aid workers were the victims of approximately 11,370 assaults by persons; a greater than 13% increase over the number of such assaults reported in 2009 (10). Almost 19% of these assaults occurred in nursing and residential care facilities alone. Unfortunately, many more incidents probably go unreported (5).

Impact on Nurse Well-Being

Workplace violence can take a heavy toll on nurses. These tolls can be emotional, mental, and physical as well as short-term or long-term. The seriousness of these injuries can vary widely ranging from minor upset to permanent injury and in worst cases, even death. (13)

This harm doesn’t stop with the nurse. The effects of workplace violence may also include effects spanning the unit the nurse works on or even the entire facility. Low morale, reduced productivity, lack of trust in employers, and fear of going to work can be results of violent events occurring to even a single co-worker.

Workplace violence can also have a financial effect on nurses and their employers related to lost time at work from injury or callouts, costs of care for treatment related to the incident (physical and/or psychological), or even legal fees. (13)

Given that incidents of workplace violence are rapidly increasing, these impacts are expected to increase as well. It is easy to see how this harm is widespread and can potentially ripple outward into the nurse’s professional and personal life. The stress and harm do not stay at work, and can spread to the nurse’s family, social interactions, and more.

Ask yourself...

- How far-reaching do you think workplace violence is?

- Can you give some examples of how workplace violence has affected you or your co-workers?

- What are some examples of how workplace violence against someone else can affect you or the patients on your unit?

Barriers to Reporting

One way to combat workplace violence is knowledge of its existence, its nature, and its frequency. Unfortunately, there are many factors that either prevent or discourage nurses from coming forward with reports when they are the victims of WPV.

A study presented in a Chinese nursing journal surveyed 325 nurses. Of these nurses, 266 were spread across 165 hospitals, and these hospitals were in 72 cities.

A total of 172 nurses (64.7%) experienced violent incidents during the past year. Of these incidents, 45.5% were reported; and the reporting rate of physical assaults (69.0%) was higher than those of verbal abuse (36.9%), threatening behavior (51.7%), and sexual harassment (60.0%). Formal reporting accounted for 25.4% (15.4% in written form and 10.0% through a computer-assisted reporting system.

Almost half of the nurses (49.6%) said that the hospital had no reporting system, or they were uncertain about the reporting system. For reasons of not reporting, 51.9% of the nurses were unaware of how and what types of violence to report, and 50.6% of the nurses believed that the hospital paid greater attention to patients rather than staff. (7)

Interestingly, almost fifty percent of the nurses surveyed had limited knowledge of a reporting system available to them. In comparison, fifty percent felt the hospital favored the patients over its employees. Combined with an actual or perceived lack of supervisory support, this encourages an environment where nurses feel powerless to protect themselves or to take proper action when threatened or harmed.

The Minnesota Nurses Association, in August of 2022, published a press release with the results of a nursing survey on the topic of workplace violence. In this survey, ninety-seven percent of the nurses surveyed observed WPV or harassment over the previous two years.

The top reasons cited by nurses who did not report workplace violence were lack of time due to overwork and understaffing, cited by fifty-eight percent of respondents, and lack of action by hospital management, cited by fifty-three percent of nurses in the survey. (4)

It would appear from these studies that many nurses feel it is futile to report incidents of workplace violence they encounter. Even if they realized an incident was reportable, they may not know how to report it or have time to do it. This perceived powerlessness and sense of futility in the face of abuse and violence will only continue to worsen unless action is taken to remove barriers to reporting and for nurses to have access to aid and support from supervisory staff.

Ask yourself...

- Can you think of any examples of when you or a co-worker tried to report an incident of workplace violence and were unable to?

- If so, what was the barrier that prevented you from reporting?

- Can you name three alternative ways to report workplace violence at your organization?

Culture of Safety

A commonly used phrase is “Culture of Safety”, but is there a standardized definition of what it is or could be? Many resources point to the safety of patients about medical errors, patient rights, and protecting the patient’s information, but few address the issue facing caregivers and especially nurses. However, there is no agreed-upon or standard definition of a “culture of safety” or what it should look like.

The American Nurses Association approaches the concept by saying, “Establishing a culture of safety in health care is essential to the security and well-being of your patients, staff, and organization. Effective nurse leaders embrace safety protocols, ensuring their organization delivers a secure, protective environment, prioritizing patients and caregivers.” (12)

Currently, only a single federal legislation is in place about the issue.

The only federal regulation currently in place is the General Duty Clause of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970. This clause requires employers to supply a work environment free from recognized hazards that are causing or likely to cause death or serious physical harm. However, the general duty clause offers no specific recommendations about managing workplace violence.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) issued guidelines for workplace violence prevention for health care and social service workers. First issued in 1996 and later updated, the guidelines are only advisory. (1)

It is paramount that nurses and other direct care providers accept the responsibility of creating policies and procedures within their organizations to define and enforce a work environment where violence is not tolerated and dealt with accordingly.

There is currently a small body of research and work on the effects workplace violence has on nurses as human beings. Most of the evidence focuses on how workplace violence increases the risk nurses pose to patients in the form of medical errors, staffing issues due to missed work, poor documentation, etc.

The main body of evidence discussing how workplace violence affects nurses is noted in research around nurse burnout. A 2020 study published by the National Health Institute (10) states, “Workplace aggression is a source of extreme socio-emotional stress, which may lead to the experience of psychological strain.

A large body of research shows that exposure to workplace aggression and violence may severely impair healthcare workers’ mental health, including symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and burnout.”

This study also shows an essential association with workplace aggression and violence targeting nurses and drastically increased levels of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and deep feelings of poor personal accomplishment. Over time, these feelings lead to complete burnout, and even worse, possibly psychological and/or physical conditions in the nurse affected.

Even with this preliminary information and research, we still have a long way to go to show the complete and far-reaching effects of workplace violence on nurses. Again, by being proactive and acting now, we as nurses can foster this research and bring the issues to light.

Ask yourself...

- How does your organization define a “culture of safety”?

- Do you agree with the definition?

- How would you define a “culture of safety” from your own perspective given your experiences and challenges?

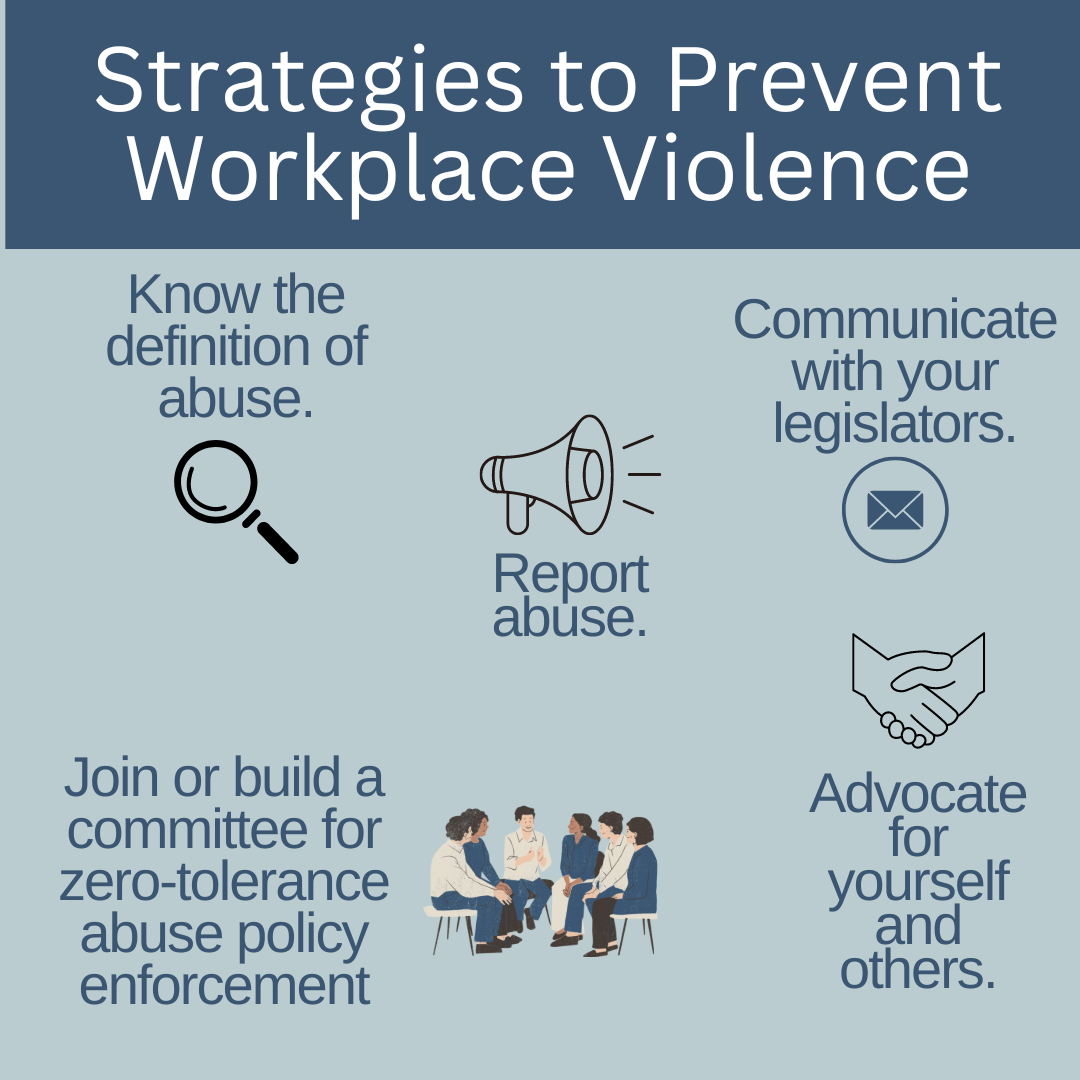

ANA Zero Tolerance Policy

In 2019, the American Nurses Association (ANA) (2) released a brief titled “Reporting Incidents of Workplace Violence.” In it, they discussed several issues surrounding workplace violence, barriers to reporting it, and recommendations to healthcare organizations on strategies relating to workplace violence.

They also established a “Zero Tolerance Policy on Workplace Violence,” which provided some definitions and several recommendations on how to deal with WPV.

The introduction to the “Culture of Safety” part of this brief is as follows:

By prioritizing, developing, and sustaining an organizational culture focused on safety, we can drive the future of healthcare to a place where patients and those who care for them are free from harm. It is one of many priorities and the overriding ethical imperatives for all leaders. (9)

The ANA also suggested a three-level prevention strategy, each with a role for the employer and the employee. Essentially, the employer’s role is to gather data, provide a “safe” work environment, non-punitive reporting, and develop programs to provide a safe work environment for nurses. The employee’s role is to participate in implementing and evaluating said programs.

Unfortunately, these are only suggestions; employers do not have to implement programs or services to protect employees against workplace violence. Also, healthcare employers do not have to report incidents to JCAHO, who consider workplace violence as “sentinel events”.

Ultimately, it falls on the nurses and employees directly affected by WPV to assume the charge against workplace violence, hold employers accountable, communicate with local and state legislators, and effect change to protect themselves.

Ask yourself...