Nevada APRN Bundle

Contact Hours: 45

Author(s):

- Sarah Schulze MSN, NP

- Morgan Curry BSN, RN

- Tracey Long PHD, APRN-BC, CCRN, CDCES, CNE, COI

- Abbie Schmitt MSN, RN

- Madeira Fountaine MSN, RN, PHN

- Amy White, CNO, RN

- Maureen Sullivan-Tevault MS, BSN, RN, CEN, CDE

- Amanda Marten MSN, FNP-C

- Edith Fomuso MSN, CCM, RN

- Sadia A. MPH, MSN, WHNP-BC

- Cathleen Adams CNO, RN CENP

- Charmaine Robinson MSN-Ed, BSN, RN

- R.E. Hengsterman MSN, RN, MA

- Karson Carter RN,BSN, CPN

Course Highlights

- In this course, we will learn about identifying ways that people of minority groups experience healthcare differently than other patients.

- You’ll also learn how syndromic surveillance is used in identifying potential acts of bioterrorism, and the reporting procedures and use of the Health Alert Network.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of the clinical criteria for prescribing oral STI medications.

Nevada Cultural Competence in Nursing (DEI Requirement)

Pretest

Please complete the evaluation below prior to reading any of the course material.

Introduction

Modern medicine has undoubtedly made many technological advancements over the last few decades, forging the way for highly intricate diagnostic and treatment methods and improving the quality and longevity of many lives.

In order to truly keep up with changing times, healthcare professionals must consider much more than the technical aspects of healthcare delivery. They must take a closer look and a more conscientious approach to the way in which care is delivered, particularly across a wide variety of demographics and characteristics. Ensuring care is delivered with empathy, respect, and equity, as well as noting and honoring a patient’s differences, is how care transforms from good to truly great.

Practicing diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and cultural competence in nursing professions must become a standard.

Health Disparities

When covering cultural competence in nursing, a provider must know that each patient is a unique individual. However, some characteristics, such as race, gender, age, sexual orientation, or disability, can create gaps in the availability, distribution, and quality of healthcare delivered.

These gaps can create lasting negative impacts on patients mentally, physically, spiritually, and emotionally and even lead to poorer outcomes than patients not within a special population. Modern healthcare professionals have a responsibility to learn to identify risks, provide sensitive and inclusive care, and advocate for equity in much the same way that they have a responsibility to learn how the human body, medications, or hospital equipment works.

Ask yourself...

- What health disparities have you encountered?

- How have you seen health disparities impact a patient’s health?

- What resources does your facility offer to help bridge healthcare disparities?

- How has DEI impacted healthcare since you have been in practice?

- What is cultural competence?

Epidemiology

Let’s turn to data to understand the importance of cultural competence in nursing and the best practices for DEI in healthcare.

Healthy People 2020 provides a myriad of data, including countless implications for changes that need to occur in healthcare settings to ensure equitable care for all populations.

The data includes statistics such as:

- 12.6% of Black/African American children have a diagnosis of asthma, compared to 7.7% of white children (16).

- The rate of depression in women ages 65+ is 5% higher than that of men of the same age across all races (16).

- Teenagers and young adults who are part of the LGBTQ community are 4.5 times more likely to attempt suicide than straight, cisgender peers (16).

- 16.1% of Hispanics report not having health insurance, compared to 5.9% of white populations (16).

- The national average of infant deaths per 1,000 live births is 5.8. The rate for Black/African American infants is nearly double at 11 deaths per 1,000 births (16).

- 12.5% of veterans are homeless, compared to 6.5% of the general U.S. population (16).

Additional disparities are seemingly endless and point unquestionably to the fact that cultural competence and DEI awareness are no longer things that healthcare professionals can be uninformed about. The purpose of this course is to outline and explore the most common or serious healthcare disparities, address ways in which healthcare delivery needs to be adjusted, and start the conversations needed to create a new generation of healthcare professionals that will close these gaps.

Understanding DEI best practices in the health setting and possessing cultural competence in nursing are vital in making positive changes for all populations.

Ask yourself...

- Are the statistics surprising to you?

- Do the statistics above align with what you see in practice? If not, how are they different?

Implicit Bias

Before exploring the characteristics and unique circumstances of various client demographics, it is important to understand and acknowledge implicit bias. Learning information about different cultures is not enough, and clinicians’ implicit biases may impede their ability to apply that knowledge in culturally competent ways and lead to care that violates the ethics of nursing.

Implicit bias is a subconscious opinion or view that can impact attitudes and behaviors. Everyone has implicit bias; it is created through a combination of the attitudes a person was raised with and around, their lived experiences, and their effort to understand the experiences of those around them, all of which influence the lens through which we view the world. This differs from explicit bias, which involves conscious behaviors such as slurs, harassment, or inappropriate comments. Having implicit bias is not inherently bad, but it is important to be aware of those biases and that they may influence how healthcare professionals care for their clients (29).

An easy-to-understand example is caring for a client who comes in wearing a hat with the logo of a baseball team you like. This common ground may make you feel more connected to this client, a conversation may be easygoing and familiar, and you may feel more inclined to ensure they are having a good experience. This does not mean you dislike your clients who do not share this commonality with you, but simply that the connection with this client shapes your thoughts and behaviors in a positive manner.

More often, though, we hear about implicit bias in a negative connotation as it has the capacity to impact the way clinicians feel about their clients, which spills over into the way they listen to, assess, believe, and provide care for them. Implicit bias is subtle and insidious and may go unnoticed by both the clinician and the client, but the effects are cumulative and lead to gaps in health outcomes over time. Failing to address biases may actually impact the ethics of nursing care: autonomy, justice, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and veracity (36).

Autonomy

Autonomy is the principle that clients should be respected as individuals and allowed to make their own choices about their health, bodies, and treatment plans, free from outside influence or bias. Clients will often look to healthcare professionals for guidance on what to do for their health or how to proceed with treatment. Options should be offered with information about the risks and benefits of potential treatment plans in an unbiased, nonjudgmental way so that clients can make the best and most informed decision for themselves.

Unaddressed biases could lead nurses to give nonverbal or verbal cues about what they think or expect a client to do. This could lead to subtle changes in the way care options are presented to clients or to clinicians omitting certain choices altogether, ultimately reducing the autonomy clients have over their own health.

Justice

Justice is the principle that all clients deserve fair and equitable care regardless of individual circumstances or differences. The care needed by clients from certain socioeconomic backgrounds, education levels, abilities, languages, cultures, or other unique circumstances will differ from other clients. Those needs should be considered and accommodated when planning care. Biases may lead healthcare professionals to feel that disadvantaged clients should not receive individualized care because it is a “handout,” or they may feel pity or judgment for those clients, as a result, providing unjust and inequitable care.

A common example is incarcerated clients who are just as entitled to quality healthcare as their non-incarcerated peers but are much more likely to experience biased, uncompassionate, or judgmental care.

Beneficence

Beneficence is the moral obligation to do good. Nurses acting out of beneficence will strive to prevent harm, protect clients’ rights, and work towards the best possible outcomes to improve the healthcare experience for clients. An example of a way in which implicit bias can contradict beneficence is for transgender or nonbinary clients who have a different name or pronouns than what is legally listed in their chart. Nurses with bias against these clients may not put effort into utilizing the proper pronouns of name, causing distress and emotional harm to clients and negatively impacting their experience during an already stressful time of illness or injury.

Nonmaleficence

Nonmaleficence is often associated with the Hippocratic oath and is the principle that healthcare professionals will do no harm to their clients. This principle is often understood to be of more importance than all the rest, and all other actions or principles should be conducted in such a way that they do not harm. Differences in behaviors and attitudes towards clients, including stereotyping and microaggressions, can negatively impact the client experience and the principle of nonmaleficence. Often, these types of issues will lead clients to delay or stop seeking care or will cause diagnoses, possible treatments, or preventative health measures to be missed. Even if the health outcome is good, harm is still done if clients feel uncomfortable, unsafe, or disrespected during care.

An example of how implicit bias can affect nonmaleficence is assuming an elderly client is cognitively impaired and directing questions and conversation to their caregiver. This is not only condescending and disrespectful but also increases the risk that important information needed for comprehensive care will be missed by not speaking with the client directly.

Veracity

Veracity or truthfulness is the obligation to communicate openly and truthfully with clients in a respectful, objective, and timely manner. Veracity is a key component in building trust between clinicians and clients. When implicit bias is present, clients may sense this, and the trust relationship is broken down. If they mistrust clinicians, clients may have poor compliance with treatment or not ask questions. Lack of veracity also increases risks for clients who may not have a full understanding of their care if information is omitted due to bias.

For example, a clinician may minimize a discussion about side effects from a particular form of birth control because they feel their client is young or already has enough children and needs to take birth control regardless. Their bias does not increase the risks of the method of birth control, but the client being uninformed does increase the risk of serious complications (36).

One of the first steps in addressing implicit bias is to identify it. Biases may present in many forms and impact client care in obvious or more subtle ways. If this is your first time exploring your implicit biases, it can feel overwhelming or intimidating. Understanding some of the different types of implicit bias and examples of what they might look like can help you identify biases you may be harboring or including in your nursing care.

- Halo Effect—Halo effect bias is assuming beliefs or opinions about someone based on one aspect of their appearance that is flattering or desirable. An example in healthcare would be not asking a teenage client if they vape, drink alcohol, or use drugs because they are attractive and put-together students. Assuming someone does or does not participate in certain behaviors based on their appearance may lead to missed opportunities to gather accurate information. It may create an inaccurate assessment of the client.

- Horns Effect- Similar to the halo effect, the horn effect is the bias of assigning beliefs or opinions about someone based on one aspect of their appearance that is deemed undesirable. In healthcare, this could be viewing overweight clients as lazy, irresponsible, or less worthy of treatment. It could also be seen that clients with many tattoos are involved in criminal activity.

- Confirmation Bias—Confirmation bias is seeking or paying more attention to information that confirms an opinion or belief rather than seeking information that disproves it. It is equivalent to “seeing what you want to see.” In healthcare, this could mean accepting a previously given diagnosis even when additional data contradicts it or a client doesn’t quite meet the criteria.

- Affinity Bias– Affinity bias is the unconscious preference for people who look or behave similarly to oneself. There is a natural tendency to feel more comfortable around people of similar backgrounds, appearances, or ways of speaking and to feel less comfortable around those who are different in these areas. This bias can lead nurses to provide care that is more compassionate or with more attention to detail for clients who are like themselves. However, they also risk providing care that is of lower quality care or less empathetic to clients who are very different from themselves.

- Attribution- Attribution bias is the tendency to explain a person’s behavior as being part of their character rather than evaluating any situational factors. This could be assuming a client who is late to an appointment is lazy or does not care about their health, when in reality they may have some very stressful external factors affecting them. Attribution bias may also be assuming clients who are noncompliant with medication are passive about their health, when in reality they may not be taking the medication because of an undesirable side effect they are afraid to mention.

- Gender Bias- Gender bias is assuming a person’s abilities, intelligence, role, or symptom severity based purely on their gender. Nurses may have gender bias against clients by assuming a female client is “chatty” or “dramatic” if she is describing multiple symptoms or issues during a visit. Nurses can hold gender bias against other healthcare professionals, assuming a woman in scrubs is a nurse and a man in scrubs is a doctor, when in reality either role may be occupied by either gender.

- Contrast Bias– Contrast bias is the effect of comparing 2 separate things against each other rather than judging them as individual circumstances. This is commonly seen through the hiring process when 2 candidates may be compared to each other and one is deemed less qualified in comparison, even though they both may be well-qualified candidates. In healthcare, this can occur when comparing clients’ responses to procedures or pain. One client in labor may be stoic and quiet while another is vocal and higher energy. Both are normal responses to pain, but the more vocal client may be seen as difficult or dramatic when compared to the quiet client.

- Anchoring Bias– Anchoring bias is being “anchored” or only focusing on one initial piece of information about a situation, which then influences a person’s decision-making ability for the rest of the situation. An example in healthcare is a client with a history of congestive heart failure (CHF) presenting to the emergency department with a complaint of shortness of breath (SOB). Since SOB is a common symptom of progressing CHF, clinicians may be initially inclined to think this is the source of the symptom. This may lead to a delay in testing or diagnosis for other potential causes of SOB, such as a pulmonary embolism. By being anchored to the initial thoughts about this client’s case, a provider risks a missed diagnosis or poor outcome.

- Conformity Bias– Conformity bias is acting similar to those around you, despite your own views or other information about a topic. In healthcare, an example of conformity bias is a nurse working in an office where many staff members have a negative or judgmental view of clients with Medicaid insurance. The nurse may not have any experience with insurance or have noticed a difference in clients based on their insurance type, however the exposure to frequent negative comments about Medicaid eventually rubs off on the nurse who now shares a negative view of these clients.

- Name Bias- Name bias is an assumption about a person’s gender, race, or ability to fluently speak English prior to even meeting them. In healthcare, name bias can be related to clients whenever their name is viewed in the chart or can also be related to the hiring of healthcare professionals when recruiters are reviewing job applications. Assumptions about a person’s name are often baseless, and others may change their opinion once they meet someone. Still, this bias could lead to missed opportunities for those without the “preferred” sounding name, usually Western or European, white, or even male. (37,38)

Implicit biases in healthcare may not just be about nurses’ behavior towards clients but can also exist within healthcare itself. Nurses may have certain biases against other nurses who are of different age, experience level, gender, race/ethnicity, or sexual orientation than themselves. They may assume those nurses are less capable, intelligent, efficient, or have a lower work ethic. This may lead to resentment and tension in a department, which can hurt the unit’s teamwork and cohesiveness. A department with staff tension and a lack of teamwork will also indirectly hurt client care, as staff are more likely to be stressed, burned out, or distracted.

On a systemic level, implicit bias from those in positions of power has led to 1) largely underrepresented minority races as healthcare providers (in 2018, 56.2% of physicians were white, while only 5% were Black and 5.8% Hispanic)(30), 2) lack of support, acceptance, and resources for LGTBQ individuals in the home, workplace, school, and community, 3) varied assessment of disability and inconsistent reporting throughout the population (reports range from 12% to 30%)(31), 4) difficulty obtaining health insurance or utilizing health resources for already at-risk groups.

Ask yourself...

- Consider the facility you work at and the different types of clients you encounter there. When you meet a new client, are there any characteristics that you use to make assumptions about them, such as age, race, gender, education level, sexual orientation, or gender identity?

- Choose one of the types of implicit bias from above and think of a time when you held this type of bias (be honest, everyone has implicit biases).

- Has there ever been a time when you experienced the receiving end of implicit bias? Which type do you think it was?

- What is implicit bias?

- What is the ethical principle of autonomy?

- What is an example of justice in nursing?

- How would you explain beneficence?

- What is non-maleficence?

- Define veracity?

- What types of bias have you witnessed or encountered? How did that impact your care?

Race and Ethnicity

One of the most significant disparities in healthcare, and the one garnering the most attention and campaigns for change in recent years, is race and ethnicity. However, when covering the best practices for cultural competence in nursing, it is essential that we go over this topic. Studies in recent years have revealed that minority groups, particularly Black Americans, are sicker and die younger than white Americans. Examples include:

Current data shows that Black men are more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer and 2.5 times more likely to die from it than their white peers. A 2019 study through the University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center explored prostate cancer outcomes when factors such as access to care and standardized treatment plans were controlled. They found that outcomes were comparable, and Black men experienced similar mortality to the white men in the study, implying that they did not “intrinsically and biologically harbor a more aggressive disease simply by being Black” (11).

A 2020 study found that Black individuals over age 56 experience a decline in memory, executive function, and global cognition at a rate much faster than their white peers, often as much as 4 years ahead in terms of cognitive decline. Data in this study attribute the difference to the cumulative effects of chronically high blood pressure, more likely to be experienced by Black Americans (20).

Black women experience twice the infant mortality rate and nearly four times the maternal mortality rate of non-Hispanic white women during childbirth. One in five Black and Hispanic women report poor treatment during pregnancy and childbirth by healthcare staff. Studies indicate that in addition to biases within the healthcare system, some of these poor outcomes may also be attributed to cumulative effects of lifelong inferior healthcare (1).

Lack of health insurance keeps many minority patients from seeking care at all. 25% of Hispanic people are uninsured and 14% of Black people, compared to just 8.5% of white people. This leads to a lack of preventative care and screenings, a lack of management of chronic conditions, delayed or no treatment for acute conditions, and later diagnosis and poorer outcomes of life-threatening conditions (4).

Emerging data indicates that hospitalizations and deaths from COVID-19 are disproportionately affecting Black and Hispanic Americans, with Black people being 153% more likely to be hospitalized and 105% to die from the disease than white people. Hispanic people are 51% more likely to be hospitalized and 15% more likely to die from COVID-19 than white people (21).

The potential reasons are many, from genetics to environmental factors such as socioeconomic status, but data repeatedly shows that these factors are not enough to account for the disproportionate health outcomes when you correct for age, socioeconomic status, and other demographics; it eventually comes down to inequity in the structure of the healthcare systems in which we all live.

For example:

- Medical training and textbooks are mostly commonly centered around white patients, even though many rashes and conditions may look very different in patients with darker skin or different hair textures (13).

- There is also a lack of diversity in physicians; in 2018, 56.2% were white, while only 5% were Black and 5.8% Hispanic. More often than not, patients will see a physician who is a different race than they are, which can mean their particular experiences as a minority and how that relates to their health are not well understood by their physician (2).

- While the Affordable Care Act increased the number of people who have access to health insurance, minority patients are still disproportionately uninsured, which leads to delayed or no care when necessary (4).

- Minority patients are also often those living in poverty, which goes hand in hand with crowded living conditions and food deserts due to outdated zoning laws created during times of segregation. This means less access to nutritious foods, fresh air, or clean water, which has negative effects on health overall (21).

- Much of the issues with modern healthcare come from a history of racism as the healthcare system was being built. There is a long history of mistreatment, lack of consent, and lack of representation of Black clients, which has shaped some modern attitudes about care delivery as well as being passed down as generational trauma that affects the way Black clients seek out and participate in care. It is important for clinicians to understand where some of this mistrust or skepticism comes from and not misinterpret hesitancy as passivity.

Examples of historic racism include:

- One of the most infamous examples is the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, which took place in 1932 and included 600 Black men, about two-thirds of whom had syphilis. During the study, the men were told that they were being treated for syphilis, and they were periodically monitored for symptom progression and blood collection. In exchange, they were given free medical exams and meals. Informed consent was not collected, and participants were given no information about the study other than that they were being “treated for bad blood”, even though no treatment was actually administered. By 1943, syphilis was routinely and effectively treated with penicillin, however the men involved in the study were not offered treatment and their progressively worsening symptoms continued to be monitored and studied until 1972 when it was deemed unethical. Once the study was stopped, participants were given reparations in the form of free medical benefits for the participants and their families. The last participant of the study lived until 2004 (33).

- The “father of modern gynecology,” Dr. J. Marion Sims, is another example steeped in a complicated and racially unethical past. Though he did groundbreaking work on curing many gynecological complications of childbirth, most notably vesicovaginal fistulas, he did so by practicing on unconsenting, unanesthetized, Black enslaved women. The majority of his work was done between 1845 and 1849 when slavery was legal, and these women were likely unable to refuse treatment, sometimes undergoing 20-30 surgeries while positioned on all fours and not given anything for pain. Historically, his work has been criticized because he achieved so much recognition and fame through an uneven power dynamic with women who have largely remained unknown and unrecognized for their contributions to medical advancement (39).

- Another example is the story of Henrietta Lacks, a young Black mother who died of cervical cancer in 1951. During the course of her treatment, a sample of cells was collected from her cervix by Dr. Gey, a prominent cancer researcher at the time. Up until this point, cells being utilized in Dr. Gey’s lab died after just a few weeks, and new cells needed to be collected from other patients. Henrietta Lacks’ cells were unique and groundbreaking in that they were thriving and multiplying in the lab, growing new cells (nearly double) every 24 hours. These highly prolific cells were nicknamed HeLa Cells and have been used for decades in developing many medical breakthroughs, including studies involving viruses, toxins, hormones, and other treatments on cancer cells and even playing a prominent role in vaccine development. All of this may sound wonderful, but it is important to understand that Henrietta Lacks never gave permission for these cells to be collected or studied and her family did not even know they existed or were the foundation for so much medical research until 20 years after her death. There have since been lawsuits to give family members control over what the cells are used for, as well as requiring recognition of Henrietta in published studies and financial payments from companies who profited off of the use of her cells (34).

- Breastfeeding trauma, wherein Black enslaved women were used as wetnurses, forced to separate from their own babies so they could feed the infants of their owners. This is passed down as generational trauma and lower breastfeeding initiation and continuation rates among Black clients (35).

When considering all of the above scenarios, the common theme is a lack of informed consent for Black patients and the lack of recognition for their invaluable role in society’s advancement to modern medicine. It only makes sense that these stories, and the many others that exist, have left many Black patients mistrustful of modern medicine, medical professionals, or treatments offered to them, particularly if the provider caring for them doesn’t look like them or seems dismissive or unknowledgeable about their unique concerns. Awareness that these types of events occurred and left a lasting impact on many generations of Black families is incredibly important in order for medical professionals to provide empathetic and racially sensitive care.

Potential solutions to these problems are in the works across many fronts, but the breakdown and resetting of old institutions will likely require change on a broader political level.

Medical school admission committees could adopt a more inclusive approach during the admission process. For example, they pay more attention to the background and perspectives of their applicants and the circumstances/scenarios in which they came from than their involvement in extracurriculars (or lack of) and former education. Incentivizing minority students to choose careers in healthcare and investing in their retention and success should become a priority in the admissions process (13). This is one of the main drivers and only possible paths to having minority representation in healthcare systems nationwide.

Properly training and integrating professionals like midwives and doulas into routine antenatal care and investing in practices like group visits and home births will give power back to minority women while still giving them safe choices during pregnancy (1).

Universal health insurance, basic housing regulations, access to grocery stores, and many other socio-political changes could also work towards closing the gaps in accessibility to quality healthcare, which may vary by geographic location.

Ask yourself...

- Did you ever receive a service or do business with a company you felt treated unfairly? Did you feel like that experience tainted your view or made you hesitate the next time you needed a similar service?

- Imagine you received a phone call from your healthcare provider’s office letting you know that the last time you were there, they collected blood work that was used for a medical experiment. Do you think you would be surprised by this? Confused? Maybe even angry?

- Now imagine you learned the experiment your blood work was used for made millions of dollars for your clinic. How would this change the way you felt? Would you feel entitled to some of that profit?

- How have you seen race and ethnicity impact healthcare?

- How do personal experiences impact the care provided to patients?

LGBTQ

Another highly at-risk group for healthcare inequity are members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transexual, and Queer (LGBTQ) community. When practicing cultural competence in nursing, the provider must become aware of how vulnerable this population is, especially in healthcare settings. Risks and examples of disparities within the LGBTQ community include:

- Youth are 2-3 times more likely to attempt suicide.

- More likely to be homeless.

- Women are less likely to get preventative screenings for cancer.

- Women are more likely to be overweight or obese.

- Men are more likely to contract HIV, particularly in communities of color.

- Highest rates of alcohol, tobacco, and drug usage

- Increased risk of victimization and violence

- Transgender individuals are at an increased risk for mental health disorders, substance abuse, and suicide and are more likely to be uninsured than any other LGB individuals (17)

Current data suggests that most of the health disparities faced by this group of people are due to social stigma, discrimination, lack of access or referral to community programs, and implicit bias from providers, leading to missed screenings or care opportunities.

Support systems and social acceptance are strongly linked to the mental health and safety of these individuals. Lack of support and acceptance in the home, workplace, or school leads to negative outcomes. Also, a lack of social programs to connect LBGTQ individuals to each other and build a community of safety and acceptance creates further gaps.

There is currently still discrimination in access to health insurance and employment for this population, which can affect accessibility of quality health care as well as affordable coverage.

Following this, a compilation of recent data showcases that there are significant issues with the quality and delivery of care provided to those in the LGBTQ community.

This data includes:

- In a 2018 survey of LGBTQ youth, 80% reported their provider assumed they were straight and did not ask (18).

- In 2014, over half of gay men (56%) who had been to a doctor said they had never been recommended for HIV screening (14).

- A 2017 survey of primary care providers revealed that only 51% felt they were properly trained in LGBTQ care (25).

Although it is unclear as to whether this data stems from a lack of education or social awareness from the provider, it is evident that change needs to be made. At the root of many of the biases regarding LGBTQ clients is a lack of understanding when caring for people in this community. Healthcare professionals need to familiarize themselves with the definitions and differences in sexuality, gender identity, and the many terms within those categories to have a better understanding of how these factors affect the health and safety of clients. A glossary for reference and better understanding has been included at the end of this course.

To improve these conditions and close the gap for LGBTQ individuals, much can be done on the community level and in medical training:

- Community programs should be available to create safe spaces for connection and acceptance.

- Laws and school policies can focus on how to prevent and react to bullying and violence against LGBTQ individuals.

- Cultural competence training in medical professions needs to include LGBTQ issues.

- Data collection regarding this population needs to increase and be recognized as a medical necessity, as it is currently largely ignored.

Providers must stay current on changes and health trends among the LGBTQ population, as healthcare delivery methods may require adjustments over time; this is critical when learning about cultural competence in nursing.

Ask yourself...

- What community resources do you have in your area for the LGBTQ community?

- What training have you had in recognizing and preventing bias with the LGBTQ community?

- How has practice changed regarding the LGBTQ community since you have been in practice?

LGBTQ Term Glossary

- Sex: A label, typically of male or female, assigned at birth, based on the internal reproductive structures, external genitals, secondary sex characteristics, or chromosomes of a person. Sometimes, the label “intersex” is used when the characteristics used to define sex do not fit into the typical categories of male and female. This is static throughout life, though surgery or medications can attempt to alter physical characteristics related to sex.

- Gender: Gender is more nuanced than sex and is related to socially constructed expectations about appearance, behavior, and characteristics based on gender. Gender identity is how a person feels about themselves internally and how this matches (or doesn’t) the sex they were assigned at birth. Gender identity is not related to who a person finds physically or sexually attractive. Gender identity is on a spectrum and does not have to be purely feminine or masculine and can also be fluid and change throughout a person’s life.

- Cisgender: When a person identifies with the sex they were assigned at birth.

- Transgender: When a person identifies with a different sex than the one they were assigned at birth. This can lead to gender dysphoria or feeling distressed and uncomfortable when conforming to expected gender appearances, roles, or behaviors.

- Nonbinary: When a person does not identify as entirely male or female. A nonbinary person can identify with some aspects of both male and female genders, identify with certain characteristics at different times, or reject both entirely.

- Sexual orientation: A person’s identity in relation to who they are attracted to romantically, physically, and/or sexually. This can be fluid and change over time, so do not assume a client has always or will always identify with the same sexual orientation throughout their life.

- Heterosexual/Straight: Being attracted to the opposite sex or gender as your own.

- Homosexual/Gay/Lesbian: Being attracted to the same sex or gender as your own.

- Bisexual: Being attracted to people of many sexes, including your own.

- Pansexual: Being attracted to people, regardless of sex or gender presentation.

Ask yourself...

- What is the difference between cisgender and transgender?

- Define nonbinary.

- What is the difference between pansexual and bisexual?

- How would you explain the difference between sex and gender?

- What communication techniques have been helpful when obtaining a patient history and inquiring about their personal information?

Case Study:

Justin is a 44-year-old male who presents to the family practice office for an annual physical. He indicates some mild depression since a recent breakup with his long-term girlfriend but otherwise denies complaints today.

His exam is normal, and he had routine lab work at his physical last year, so none is ordered today. His PCP refers him for psychotherapy and indicates that if his depressive symptoms have not improved within 6-8 weeks, starting an SSRI may be beneficial.

Justin leaves the appointment with a referral and scheduled follow-up but nothing else. What the PCP failed to realize was that Justin ended his recent relationship to come out as gay, and he has been dating men for about 4 months now. He was not asked to update any demographic information at check-in and was embarrassed to bring up the topic on his own.

Discussion

In this case, the PCP did not have a full picture of the client’s health history and risk factors. By assuming that Justin was still heterosexual because his last partner was a woman, the opportunity to educate about risks and screen for STIs, particularly HIV, was missed. Justin also may be a good candidate for medications like PREP and could benefit from the reduced risk of contracting HIV. A discussion about this medication and whether it is a good fit for the client did not take place.

Ask yourself...

- Think about a patient you have cared for who did not come in with a significant other. Did you make any assumptions about that client’s sexual orientation or gender identity?

- Would there have been different risk screenings you needed to perform if they were part of the LGBTQ community?

- Have you ever had someone repeatedly call you the wrong name or assume something incorrect about you? How did it make you feel?

Gender and Sex

Gender and sex play a significant role in health risks, conditions, and outcomes due to a combination of factors, including biological, social, and economic elements.

Among the differences in health data related to gender are:

- Women are twice as likely to experience depression than men across all adult age groups (7).

- About 12.9% of school-aged boys are diagnosed and treated for ADHD, compared to 5.6% of girls, though the actual rate of girls with the disorder is believed to be much higher (9).

- A 2010 study showed men and women over age 65 were about equally likely to have visits with a primary care provider. Still, women were less likely to receive preventative care such as flu vaccines (75.4%) and cholesterol screening (87.3%) compared to men (77.3% and 88.8% respectively) (5).

- In the same study, 14% of elderly women could not walk one block, as opposed to only 9.6% of men at the same age (5).

- Heart disease is the leading cause of death in women, yet women are shown to have lower treatment rates for heart failure and post-heart attack care, as well as lower prevalence but higher death rates from hypertension than men (6).

It is also important to differentiate gender and sex when practicing cultural competence in nursing.

Sex is the biological and genetic differentiation between males and females, whereas gender is a social construct of differences in societal norms or expectations surrounding men and women. Knowing this differentiation is essential for someone looking to better practice cultural competence in nursing and provide equitable and inclusive care.

Some health conditions are undeniably attributable to the anatomical and hormonal differences of biological sex; for example, uterine cancer can only be experienced by those who are biologically female. Many of the inequalities listed above disproportionately burden women due to the social and economic differences they experience in society; for example, 1 in 4 women experience intimate partner violence as compared to 1 in 9 men (22).

What are the reasons for this? A lot of it has to do with how women are perceived in society, how their symptoms may present differently than their male counterparts, or how their symptoms are presented to and received by medical professionals.

For centuries, any symptoms or behaviors that women displayed (largely mental health-related) that male doctors could not diagnose fell under the umbrella of hysteria. The recommended treatment for this condition was anything from herbs, isolation, sex, or abstinence, and it is only in the last one hundred years or so that more accurate medical diagnoses began to be given to women. Hysteria was not deleted from the DSM until 1980 (27).

The Cameron study found that women were more verbose in their encounters with physicians and may not be able to fit all their complaints into the designated appointment time, leading to a less accurate understanding of their symptoms by their doctor (5).

The same study also indicated that women tend to have more caregiver responsibilities and feel less able to take time off for hospitalizations or treatments (5).

Symptoms of mental health disorders like ADHD may look different in girls than in boys. Girls who are having difficulty focusing may be categorized as “chatty” or “daydreamers” by teachers. In contrast, boys are more likely to draw attention for being hyperactive or disruptive when both are experiencing symptoms of ADHD and could benefit from treatment (10).

The way that teachers, doctors, and nurses view and respond to girls and women must be adjusted to close these gaps and ensure equitable care for men and women.

- Children who are struggling in school should be examined more comprehensively, and differences in learning styles should be widely understood.

- Screening questionnaires and standard preventive care are used when caring for clients in primary care.

- Social services should be utilized to help determine whether women are neglecting their own healthcare needs due to responsibilities at home.

- Medical professionals must be trained in the history of inequality among women, particularly regarding mental health, and proper, modern diagnostics must be used.

- The differences in communication styles of men and women should be understood when caring for patients.

Ask yourself...

- In what ways do you think the history of “hysteria” in women may still be subtly present today?

- Think about the way we use the word hysterical in language. Now, consider that the word is related to having a uterus and how this might influence cultural views of women.

- Consider that girls are diagnosed with ADHD about half as often as boys. In what ways do you think their symptoms differ?

- How does your communication change when working with different genders and ages?

- Which age group do you feel has the most biased challenges and barriers?

- Do you feel that you receive bias as a healthcare provider due to your age/gender? How do you overcome that?

- What did the Cameron study reveal?

- How can education reduce the incidence of bias and improve healthcare?

Religion

Religion can impact when patients seek care, which treatments they participate in, and how they perceive their care. Even advanced healthcare technology can be perceived as unsatisfactory if it violates patients’ religious preferences, so it is very important for healthcare professionals to be aware of certain religious preferences to provide the most competent and sensitive care possible.

Consequences of culturally incompetent care include:

- Negative health outcomes due to not participating in care that violates their religious beliefs.

- Patient relationships with healthcare professionals can suffer if they feel disrespected or misunderstood, causing patients to delay or avoid seeking care altogether.

- Dissatisfaction with care which can even lead to long-term trauma surrounding major events like birth, death, or chronic disease if a patient felt uninvolved or disrespected in their care (26).

There are many religions with different practices and ordinances, but we will cover some of the more major and common implications regarding health practices here. Typically, views on pregnancy/birth, death, diet, modesty, and treatment for illness are the most important areas for healthcare professionals to understand. Providers must continue to educate themselves on the practices and preferences of various religions; it is essential to practicing cultural competence in nursing.

Disclaimer: Please note that each religion has many variations, and not all practices may be the same. The following information has been sourced from “Cultural Religion Competency in Clinical Practice,” written by Drs. Diana Swihart, Siva Naga S. Yarrarapu, and Romaine L. Martin (26).

Buddhism

They study and meditate on life, cause and effect, and karma, working towards personal enlightenment and wisdom. They believe the state of mind at death determines their rebirth and prefer a calm and peaceful environment without sedating drugs. They have ceremonies around birth and death. Their diet is usually vegetarian (26).

Christian Science

Based on the belief that illness can only be healed through prayer, they typically choose spiritual healing for disease or illness prevention and treatment. They often refuse vaccines and delay treatment for acute illnesses. They avoid tobacco and alcohol but have no other dietary restrictions (26).

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints/Mormon

Heavily family-oriented, family involvement in major health/life events is important. Strict abstinence outside of heterosexual marriage. Fasting is required monthly, but it is exempt during illness. Blood or blood products are accepted. Abortion is prohibited unless it is a result of rape or the mother’s life is in danger. Two elders present to bless those ill or dying (26).

Hinduism

Centers on leading a life that allows you to reunite with God after death. Believes in reincarnation, so the environment around dying people must be peaceful. The presence of family and a priest during the end of life is preferable. After death, the body is washed and not left alone until cremated. Euthanasia is forbidden. The right hand is used for eating (26).

Islam

Belief in God and the prophet Abraham. Prayer is required five times daily. Observe Ramadan, a month of fasting and abstinence during daylight (children and pregnant women are exempt from fasting). Autopsies should only be performed if legally necessary. Must eat clean, halal food and excludes pork, shellfish, and alcohol. Female patients require female healthcare providers. Abortion is prohibited (26).

Jehovah’s Witness

Believe the destruction of the present world is coming and true followers of God will be resurrected. Do not celebrate birthdays or holidays. Believe death is a state of unconscious waiting. Euthanasia prohibited. Refuse blood and blood products. Abortion is prohibited. Pregnancy through artificial means (IUI, IVF) is prohibited (26).

Judaism

Belief in an all-powerful God and varying levels of interpretation/observance of laws and traditions. Cremation is discouraged or prohibited. Prayer is important for the sick and dying, after death the body is not left alone. Must eat kosher foods, which excludes pork. Amputated limbs must be saved and buried where the person will one day be buried. Abortion is allowed in certain circumstances (26).

Protestant

Christian faith formed in resistance to Roman Catholicism. Autopsy and organ donation are acceptable. Euthanasia is not acceptable. There are no restrictions on diet or traditional Western medicine treatments (26).

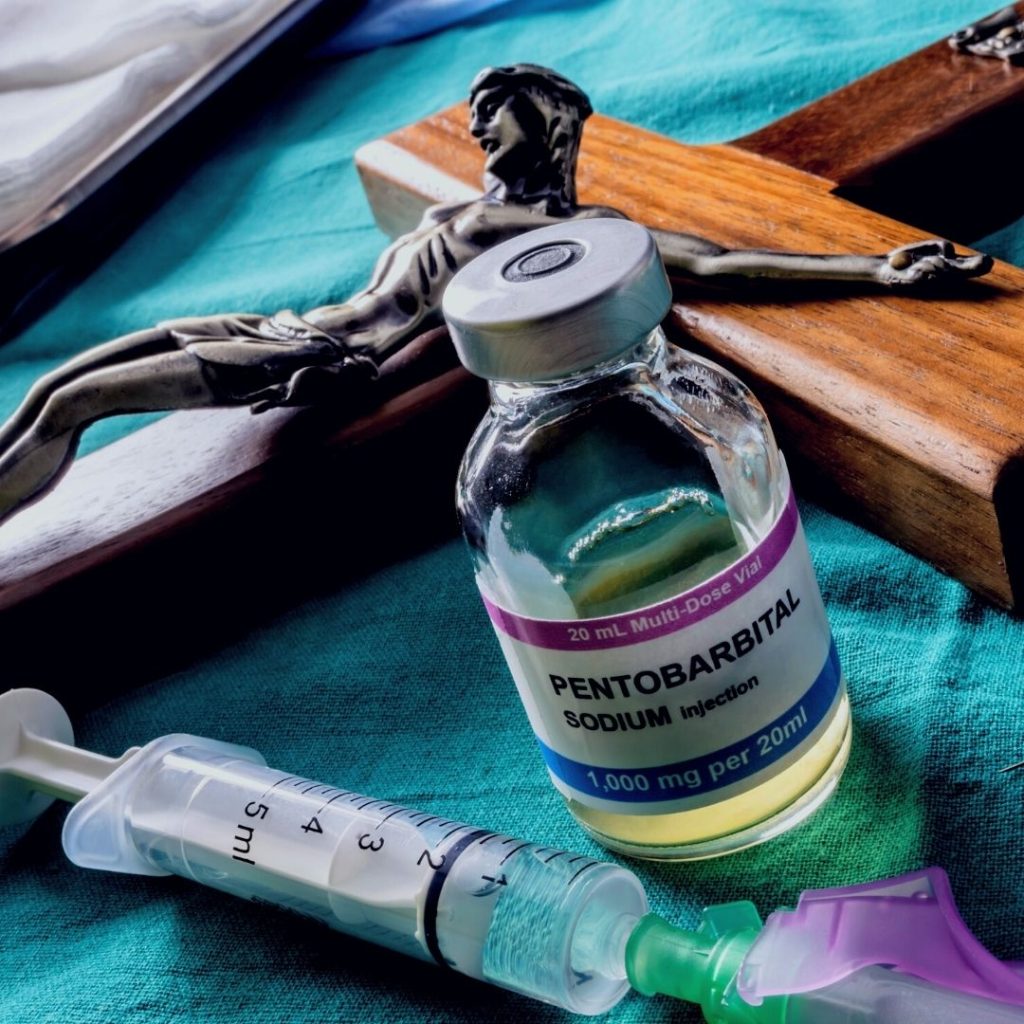

Roman Catholicism

Christian faith is steeped in tradition and observance of sacraments. The clergy is present at the end of life for the sacrament of Last Rites. Avoid meat on Fridays during Lent. Mass and Communion on Sundays is an obligation, and they may require a clergy member to visit during hospitalization. Abortion and birth control (other than natural family planning) are prohibited. Artificial conception is discouraged. Newborns with a grave prognosis need to be baptized (26).

To better practice cultural competence in nursing and improve the quality of care given that respects a patient’s faith and religious boundaries, one should focus on:

- Understanding basic differences and preferences with various religions and providing training for staff.

- Encouraging family to participate in health decision-making where appropriate.

- Providing interpreters where needed.

- Promoting an environment that allows clergy, healers, or other religious figures of comfort to visit and participate in care if desired.

- Providing dietary choices that are considerate of religious dietary preferences.

- Recruiting staff that are minorities or of various religions.

- Respecting a client’s views on controversial topics such as pregnancy/birth, death, and acceptance or decline of treatments, even if it conflicts with staff members’ own beliefs (26).

Ask yourself...

- Imagine you work on a maternity unit and are caring for a new mother who observes the Islamic faith. What needs might she have to feel respected and comfortable with her care?

- Consider how meeting or unmet religious needs might impact a client’s perception of their care, regardless of the health outcome.

- In what ways do you think met or unmet spiritual needs might impact care long after it has occurred, especially during times of birth or death?

- What faith resources does your facility offer to patients in your facility?

- How has religion impacted healthcare in your practice? When has it helped, and when has it created more challenges?

- What are the consequences of incompetent care?

- What is the difference between Christian Science and Protestant Christianity?

- What religion might a patient refuse a blood transfusion?

- How do ethics impact culturally competent care?

- Do you have a chaplain at your facility? How do they help provide culturally competent care?

Case Study

The nurse is caring for a terminally ill 78-year-old woman, Patricia. Several weeks ago, the client and her family decided that when the disease progressed, she would like to be placed in hospice and die at home without extraordinary measures or resuscitative efforts. The family is Roman Catholic and has also requested a priest be present to administer Last Rites.

Patricia was placed in hospice earlier this week, and her condition has worsened to the point where death is near, and the priest has been called in. The nurse assists with clearing and tidying the space around Patricia’s bed and has brought additional seating for family members. The priest performs the sacrament of Last Rites, and the family sits around the bed and prays together. The nurse administers pain medication on occasion, but for the most part, it allows space for the family’s religious needs. After a few hours, Patricia dies, and the family continues to sit with her. They are sad, but overall, there is a sense of peace.

The nurse checks on the family a few weeks later as part of a follow-up program for grieving families. Patricia’s husband and children all agree that while they are grieving her loss, they feel a sense of spiritual peace with the time surrounding her death, and they know it is what she wants.

Discussion

This is an example of how attention to the beliefs and wishes of clients plays an important role in client and family perception of care received compared to the overall health outcomes. This client was terminally ill, so the health outcome was never going to be recovery or disease treatment. The client’s comfort level surrounding the end of life and the grieving process for the family afterward were both facilitated by making space for religious and spiritual needs in addition to medical care.

Ask yourself...

- Why do you think discussing plans such as Patricia’s ahead of time is important?

- How might this scenario have played out differently if the family had not planned and Patricia had gone to the emergency department with acute symptoms?

- How do you think an alternative scenario might have affected the grieving process for the family?

Age

As the Baby Boomer generation ages, there is a growing number of older adults in the U.S. In 2016, there were 73.6 million adults over age 65, a number which is expected to grow to 77 million by 2034. As of 2016, 1 in 5 older adults reported experiencing ageism in the healthcare setting (24). As the number of older adults needing healthcare expands, the issue of ageism must be addressed. For providers looking to improve cultural competence in nursing practices, it is vital that ageism is addressed as it flies under the radar. Ageism is defined as stereotyping or discrimination against people simply because they are old.

Ways in which ageism is present in healthcare include:

- Dismissing is a treatable condition as part of aging.

- Overtreating natural parts of aging as though they are a disease.

- Stereotyping or assuming the physical and cognitive abilities of a patient purely based on age.

- Providers are less patient, responsive, and empathetic to patients’ concerns. They do not talk down to patients or explain things because they believe they are cognitively impaired.

- Elderly patients may internalize these attitudes and seek care less often, forgo primary or preventative screenings, and have untreated fatigue, pain, depression, or anxiety

- Signs of elder abuse may be ignored or brushed off as easy bruising from medication or being clumsy (24).

There are many reasons why ageist attitudes in healthcare may occur, including:

- Misconceptions and biases among staff members, particularly those who have worked with a frail older population, assume all elderly people are frail.

- Lack of training in geriatrics and the needs and abilities of this population.

- Standardizing screenings and treatments by age may help streamline the treatment process but can lead to stereotyping.

- Changing this process and encouraging an individual approach may be resisted by staff and viewed as less efficient.

In order to combat ageism and make sure healthcare is appropriately informed to provide respectful, equitable care:

- Healthcare professionals can adopt a person-centered approach rather than categorizing care into groups based on age.

- Facilities can adopt practices that are standardized regardless of age.

- Facilities can include anti-ageism and geriatric-focused training, including training about elder abuse.

- Healthcare providers can work with their elderly patients to combat ageist attitudes, including internalized ones about their own abilities (24).

On the opposite end of the lifespan, children are vulnerable to gaps in care due to assumptions about their cognitive capacity to participate in their care. Healthcare professionals may ignore or minimize communication from young clients, dismissing their concerns as trivial or something to be handled by adults.

This is partly because most medical decisions require parental consent for anyone under the age of 18, with some exceptions for sensitive issues like STIs, depending on your state. However, just because the final decision-making authority lies with the parents doesn’t mean that children and teens have no opinions or desire to be a part of their care (32).

Children also may exhibit behaviors that are less cooperative than adults due to pain, fear, or illness. This is developmentally appropriate and should not be labeled as “difficult” or “bratty” but approached with empathy and an understanding of different developmental levels.

Different approaches include:

- Distractions such as toys, songs, videos, and comforts like hugs or breastfeeding should be used for babies and toddlers who are too young to understand what is happening.

- Play can be used for preschoolers to help demonstrate wearing hospital gowns/shoes/caps, giving medicine, or changing bandages. Preschoolers can be given simple explanations and use play to eliminate some of the unknown and prepare for hospital or clinic experiences.

- School-age children can be given more detailed information and may enjoy picture books or stories. They should be given the opportunity to ask questions that should be answered honestly and not dismissed with responses like “You don’t need to worry.”

- Teenagers should be included in a full discussion of the risks versus benefits of treatment plans. More advanced information or pamphlets and reading materials can be given about the disease process or treatment. This age group strives for autonomy and should be treated respectfully, allowed to participate in the decision-making process, and given privacy when possible and appropriate. Responsibility for their health should be shifted to them while still under the supervision of an adult. Teenagers who are taken seriously and given respect as individuals are more likely to form a trusting rapport with healthcare professionals, which is,, in turn,, necessary for their cooperation and compliance with treatment plans (32).

- It should also never be assumed that teenagers are “too young” to be engaging in risky behaviors such as smoking, drugs, alcohol, or sexual activity. Making assumptions opens the door for missed screenings and preventative care (32).

Child Life specialists are a wonderful resource that should be utilized whenever available; these professionals are licensed in child development and assist with coping and education for children and adolescents in the hospital or clinic setting. They can be present for situations ranging from a simple blood draw to disclosing a terminal diagnosis (32).

Age-specific treatment requirements change across the lifespan, and an important part of cultural competence is familiarity with the unique needs, strengths, and challenges of each age group. Familiarity with Erikson’s stages of development can help clinicians better understand their client’s needs and customize care accordingly.

A brief review of Erikson’s stages of development is included below.

- Trust vs. Mistrust, birth to 2 years: Infants and young toddlers in this stage are completely dependent on others to meet their needs. Their communication is very limited (crying), and, if cared for, they quickly learn that their needs will be met and that they are safe. If infants in this stage receive poor care, they may be fearful and struggle to trust that their needs will be met.

- Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt, 2-3 years: At this stage, toddlers are seeking more control over their choices and bodies (and may even have tantrums when they want control). Skills such as feeding themselves, getting dressed, communicating more effectively, helping with small tasks, and potty training provide a sense of confidence. If toddlers are not given some control over their own choices and bodies, they may doubt their abilities or feel shame.

- Initiative vs Guilt, 3-5 years: In this stage, children learn to explore, make decisions, and assert themselves in social interactions. If allowed freedom to explore the effect of their choices and interactions, children will develop a sense of initiative. If they are repressed through control or criticism, they will develop a sense of guilt.

- Industry vs Inferiority, 6-11 years: In this stage, children work to improve their abilities and seek recognition of their competence. If encouraged and praised, children will develop a sense of confidence. If ridiculed or discouraged, they will doubt their abilities.

- Identity vs Confusion, ages 12-18 years: This is the period of adolescence which is famously tumultuous. At this stage, individuals work to better understand their values, interests, and sense of self separate from the family unit. They seek independence and control over their appearance, how they spend their time, and their acceptance in a peer group, which is important. Adolescents who receive positive reinforcement for their individuality will develop a strong sense of self. Those who do not receive positive reinforcement will lack confidence and feel insecure.

- Intimacy vs. Isolation, 19-40 years: In this stage, adults work to form deeper and more intimate relationships through romantic partners and friendships. Success during this stage depends on how successfully a person achieved the previous stages. Those who are able to form strong relationships with others feel a sense of intimacy and contentment, whereas those with poor or unstable relationships will feel isolated and lonely.

- Generativity vs Stagnation, 40-65 years: During this stage, adults work to create and solidify a good and productive life, contributing to the world through careers, family, and community engagement. Successful people will feel a sense of connection and motivation; those who are unsuccessful may feel disconnected or stagnant.

- Integrity vs Despair, 65+: In this stage, older adults begin to look back on their lives and evaluate the impact or goals they have accomplished or failed to accomplish. Adults who feel proud or accomplished with all they have done will have a sense of integrity and satisfaction, whereas those with many regrets or lack of pride will feel despair or bitterness. (41)

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever cared for two elderly patients of the same age who seemed drastically different in their overall health and independence? Why do you think that is?

- Do you think seeing a client’s age on their chart (either very young or very old) influences how you feel about them before you even meet them?

- Think about Erikson’s developmental stages. Why do you think providing school-age children with accurate information about their care and answering their questions, rather than dismissing them, is important?

- What are the different approaches that can help provide care to children?

- What is agism?

- Do you have a child life specialist at your facility? What role do they play?

- What additional resources do you have at your facility to help manage care in varying age groups/

- What education can you provide to parents about the stages of development?

Case Study

Sydney is a 17-year-old client who presents to the pediatric office alone with a complaint of dysuria. She has been coming to this office for years but has never spoken with her nurse practitioner alone, so she is feeling nervous, particularly given the nature of her symptoms.

She reports pelvic pain and dysuria for about 2 weeks, along with some foul-smelling yellow vaginal discharge. She admits to being sexually active with 2 partners in the last year. She reports using condoms inconsistently. She does take hormonal birth control for acne, which is listed in her chart.

On exam, she has pelvic tenderness and yellow vaginal discharge. Otherwise, her exam is normal. The NP discusses that based on her history and exam, a diagnosis of chlamydia is likely. A urine sample is collected, and the NP states it will take a day or two for results to come back, but she can be started on an antibiotic now while awaiting results.

This NP has known Sydney for many years, knows her mother well, and knows that abstinence is the preferred method of sex education taught in Sydney’s home. The NP agrees that Sydney is too young to be sexually active and feels very concerned that she has contracted an STI and decides to contact Sydney’s mother to inform her of today’s visit.

Sydney’s mother is furious at this information and prohibits Sydney from attending prom the following week. She restricts access to her phone and activities outside of school. Sydney is distraught over the conflict at home and, over the following weeks, develops depressive symptoms with suicidal thoughts. She has a sports physical for summer camp the following month but does not disclose any of her depressive symptoms to the NP as she now feels a lack of trust and that the NP just views her as a child with no autonomy.

Discussion

Consider this case and how the NP’s own implicit biases affected the care Sydney received. Now that the trust is broken between Sydney and her provider, the chances that she will seek care for future problems are small. This could result in serious negative health outcomes, particularly since she is experiencing suicidal thoughts and is at risk for self-harm.

Now imagine this same case, but instead of the NP interjecting their own biases about the client, they follow Nevada law, which allows minors to receive confidential treatment for STIs without parental consent. Sydney could be treated discreetly without her parent’s knowledge, and the NP could utilize the opportunity to discuss safe sex and the importance of using condoms. This is much more likely to result in a positive outcome for Sydney, as she will be treated for the chief complaint, as well as be empowered to practice safer sex and hopefully avoid future STIs. She will also maintain a trusting relationship with this provider and feel comfortable making appointments for future concerns.

Ask yourself...

- Do you think this case might have gone differently if Sydney had been 20 instead of 17?

- What are the risks of a teenager who does not feel she can confide in a parent or a healthcare professional when experiencing a health problem?

- The most competent form of care for Sydney should have started years ago by allowing her to speak with the NP privately at her wellness visits. How do you think Sydney’s case might have been different if she had an existing relationship of trust with this NP before she even became sexually active?

Veterans

Veterans are a unique population that faces many health concerns that are unique to the conditions of their time in service. Much of veteran health care is provided through the Veteran Affairs (VA) facilities, a nationalized form of healthcare involving government-owned hospitals, clinics, and government-employed healthcare professionals. Again, the purpose of this course is to educate providers on how to practice cultural competence in nursing; however, let’s introduce the disparities found within this population by utilizing a few statistics.

- 1 in 5 veterans experience persistent pain, and 1 in 3 veterans have a diagnosis related to chronic pain (8).

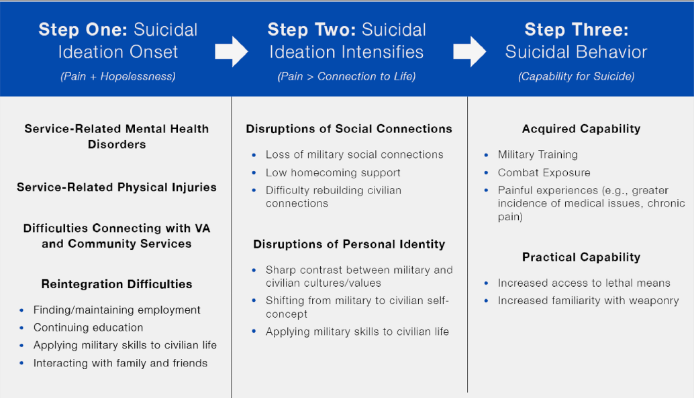

- Approximately 12% of veterans experience symptoms of PTSD in their lifetime, compared to 6% of the general population, and 80% of those with PTSD also experience another mental health disorder such as anxiety or depression (8).

- More than 1 out of every 10 veterans experiences some type of substance use disorder (alcohol, drugs), which is higher than the rate for non-veterans (8).

- In 2019, around 9% of homeless adults were veterans (28).

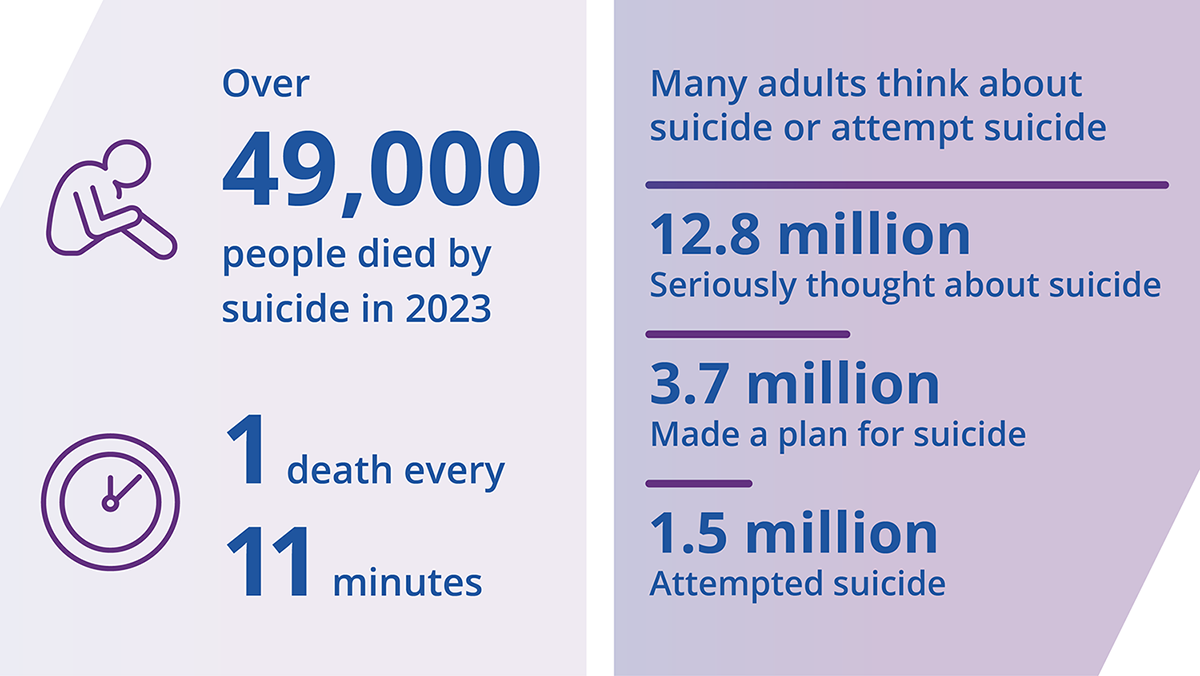

- Veterans account for 20% of all suicides in the U.S., despite only about 8% of the U.S. population serving in the military (8).

- Disparities also exist within the veteran population and veterans who are of a minority race or female experience these issues at an even higher rate.

- For example, veteran women are twice as likely to experience homelessness than veteran men (28).

The causes of these troubling issues for veterans are multifaceted; some of them relate to the nature of work in the U.S. Military and increased exposure to trauma (particularly with those involved in combat), and some of them relate to the care of veterans, and their mental health during and after their service.

- 87% of veterans are exposed to traumatic events at some point during their service (8).

- Current data suggests fewer than half of eligible veterans utilize VA health benefits.

- For some, this means they are receiving care at a non-VA facility, and for others, it means they are not receiving care at all.

- Care at civilian facilities means healthcare professionals may not fully understand veteran issues (12).

- Less than 50% of veterans returning from deployment receive any mental health services (23).

All service members exiting the military must participate in the Transition Assistance Program (TAP), an information and training program designed to help veterans transition back to civilian life, either before leaving the military or retiring. The program is evaluated annually for effectiveness and currently includes components about skills and training for civilian jobs and individual counseling regarding plans after exit.

- Adding or strengthening components of TAP surrounding mental health care and utilization of VA healthcare services would be beneficial and could help reduce disparities.

- Changing the military culture surrounding mental health to strengthen and mandate training and usage of debriefing for active duty military could be beneficial as well.

- Incentivizing the usage of the VA healthcare system for routine preventative and mental healthcare would help reach more veterans who may be in need.

- Additional training for healthcare professionals working within the VA with an emphasis on mental health disorders would ensure high-quality of care for veterans utilizing their services.

Ask yourself...

- How could trauma be better handled for these patients to reduce their risk of all the other related issues?

- Why do you think some of the reasons why half of all Veterans do not utilize VA resources could be that?

- What is a transition assistance program?

- What resources are available at your facility to help meet veteran needs?

- What has your interaction with VA healthcare been like?

- How do you think clients with veteran status might be cared for differently by civilian clinicians than those who work exclusively with veterans?

- What mental health resources do you have available to provide to veterans in need?

- What community resources do you have access to to help veterans?

Mental Illness and Disability

Disabilities are emerging as an under-recognized risk factor for health disparities in recent years, and this new recognition is a welcome change as more than 18% of the U.S (15) population is considered disabled. Disabilities can be congenital or acquired and include conditions that people are born with (such as Down Syndrome, limb differences, blindness, deafness), those presenting in early childhood (Autism, language delays), mental health disorders (bipolar, schizophrenia), acquired injuries (spinal cord injuries, limb amputations, change in hearing/vision), and age-related issues (dementia, mobility impairment).

Public health surveys vary from state to state. Still, most categorize a condition as a disability based on the following: 1) blindness or deafness in any capacity at any age, 2) severe difficulties with concentrating, remembering, and decision-making, 3) difficulty walking or climbing stairs, 4) difficulty with self-care activities such as dressing or bathing, 5) and difficulty completing errands, such as going to an appointment, alone over the age of 15 (19).

Health disparities affecting people with disabilities can include the way they are recognized, their access and use of care, and their engagement in unhealthy behaviors. To practice cultural competence in nursing, understanding the disparities that those with disabilities face is essential.

- Due to variations in the way disabilities are assessed, the reported prevalence of disabilities ranges from 12% to 30% of the population (19).

- People with disabilities are less likely to receive needed preventative care and screenings (15).

- Only 78% of women with disabilities were up to date with their pap test, while over 82% of non-disabled women were up to date with this preventative screening (19).

- People with disabilities are at an increased risk of chronic health conditions and have poorer outcomes (15).

- 27% of people with disabilities did not see a doctor when needed due to cost, as opposed to only 12% of non-disabled peers (19).

- 21% of children with disabilities were obese, compared to 15% of children without disabilities (19).

- People with disabilities are more likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors such as cigarette smoking and a lack of physical exercise than people without disabilities (15).

- During Hurricane Katrina, 38% of the people who did not evacuate were limited in their mobility or in providing care to someone with a disability (19).

Many of the health differences between those with and without disabilities come down to social factors like education, employment (finances), and transportation, which significantly affect access to care.

- 13% of people with disabilities did not finish high school, compared to 9% of non-disabled peers.

- Only 17% of people over the age of 16 with disabilities were employed, compared to nearly 64% of non-disabled peers.

- Only 54% of people with disabilities had at-home access to the Internet, compared to 85% of people without disabilities.

- 34% of people with disabilities reported both an annual income <$15,000 and access to transportation, compared to 15% and 16%, respectively, for people without disabilities.

- Fewer than 50% of people with disabilities have private insurance, while 75% of people without disabilities have private health insurance.

- Even for those insured, 16% of people with disabilities have forgone care due to cost, compared to only 5.8% of insured people without disabilities (19).

If access to necessary preventive and acute health care is to be increased for those with disabilities, much must be changed regarding the social determinants affecting this population. Community, state, and federal policy changes will be needed to provide the social and economic support these people need. Potential solutions include:

- Streamline and standardize the process of identifying people with disabilities so they can be eligible for assistance as needed.

- School programs to help people with disabilities graduate and find jobs within their ability level.

- Community participation ensures transportation, buildings, and facilities are accessible to all.

- Make internet access a basic and affordable utility, like running water and electricity.

- Address the inequities in health insurance accessibility and coverage.

- Provide social and economic support programs for parents of children with disabilities and provide transitional support as those children become adults (15).

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever cared for a patient with a serious disability? Consider how even getting to the clinic or hospital where you work might be different or more challenging than for patients without a disability.

- What resources for people with disabilities are available in your community?

- How do you think those resources might vary in surrounding areas?

- What mental health conditions and disabilities do you commonly see in your practice?

- Have you seen an increase in the incidence of mental health conditions over the last few years? Why do you think that is the case?

- What training have you had in the management of disabilities?

- What ancillary services do you have available at your facility to help manage mental health crises?

Conclusion

In short, cultural competence in nursing means that although a provider may not share the same beliefs, values, or experiences as their patients, they understand that to meet their needs, they must tailor their care delivery. Nurses are patient advocates, and it is on them to ensure they provide equitable and inclusive care to all populations.

However, cultural competence in nursing is ever-changing, and it is the provider’s responsibility to stay up-to-date in order to offer the best experience for all patients.

Bioterrorism in Nursing

Introduction

The threat of biological warfare may seem like a far-fetched idea, something only one may see in a movie. However, with the recent events of our world, it seems increasingly likely. With advancements in science and developments in microbial genetics, there is heightened concern regarding the abuse of these discoveries for acts of terrorism and war. Although regulations and procedures exist to secure the exposure or release of such pathogens in research laboratories, there is still a risk involved.

Effective preparedness for bioterrorism in nursing staff is a crucial asset to have in the management of an attack. Nurses and other healthcare practitioners play a vital role in this preparedness. It is essential that they have some knowledge of the prevention and control practices as well as knowledge of the various biological, chemical, nuclear, and radioactive agents that may be used in a potential intentional attack. Arming healthcare providers with expertise in preparedness, management, and treatment will allow for a smoother transition of action if a public health emergency ensues.