Course

Nevada HIV: Stigma, Discrimination and Bias

Course Highlights

- In this Nevada HIV: Stigma, Discrimination, and Bias course, we will learn about legal protections against discrimination for patients who are HIV-positive in Nevada and the United States.

- You’ll also learn how to recognize the forms of HIV discrimination in healthcare settings.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of effective communication strategies that respect patient privacy and promote trust for the rights and equitable treatment of HIV-positive patients.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 2

Course By:

Abbie Schmitt

MSN-Ed, RN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

One of the toughest challenges faced by people living with HIV is social stigma and discrimination. As we go through this course, please imagine a close family member or friend was recently diagnosed with HIV and you are comforting them with this life-changing news. Education is a powerful tool to reduce this stigma, as myths and inaccurate information continue to exist.

Overview of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is the virus that can destroy or impair immune system function and lead to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), which is known as the most advanced stage of HIV infection (14).

Etiology

This virus is unevenly distributed among races and genders.

- 39 million people globally were living with HIV (in 2022).

- 37.5 million adults

- 1.5 million children

- 53% of all people living with HIV were female.

- 1.3 million people became newly infected with HIV in 2022.

- Roughly 630,000 people died from AIDS-related illnesses or complications in 2022.

- At the end of December 2022, only an average of 76% of all people living with HIV were accessing antiretroviral therapy.

- 9.2 million people living with HIV did not have access to antiretroviral treatment in 2022.

- AIDS-related mortality has declined by 55% among women and girls and by 47% among men and boys since 2010.

HIV prevalence among the adult population is roughly 0.7% (15). However, it is much greater in certain populations. Populations that face the greatest impact include sex workers, homosexual men who are sexually active with men, those who inject illicit drugs, transgender individuals, and those in prison (15).

Pathophysiology

The virus attaches to the CD4 molecule and CCR5 (a chemokine co-receptor); the virus' surface fuses with the cellular membrane to enter into a T-helper lymphocyte (7). After integration in the host genome, the HIV provirus forms and then goes through transcription and viral mRNA production. HIV proteins are then produced in the host cell and can release millions of HIV particles that have the potential to infect other cells (7). This leads to the destruction of the cell-mediated immune (CMI) system, primarily by eliminating CD4+ T-helper lymphocytes, which are vital to this system.

- Acute HIV infection: Describes the period immediately after infection with HIV when an individual has detectable p24 antigen or has HIV RNA without diagnostic HIV antibodies.

- Recent infection: Describes the 6 months following infection.

- Early infection: This may refer to acute or recent infection.

Stages of HIV

Those who do not receive treatment typically progress through three stages. However, HIV treatment can slow or prevent progression of the disease. Significant advances in HIV treatment have led to such slowed progression that Stage 3 (AIDS) is less common now than in the early years of HIV.

Stages of HIV (4):

- Stage 1: Acute HIV Infection

-

- There is a large amount of HIV in the blood, making the virus very contagious.

- Flu-like symptoms are common.

- It is important for those who have symptoms and/or possible exposure to get tested.

- Stage 2: Chronic Infection

-

- Also called asymptomatic HIV infection or clinical latency.

- HIV is still active and continues to reproduce in the body.

- People may not have any symptoms or get sick during this phase but can transmit HIV.

- People who take HIV treatment as prescribed may never move into Stage 3 (AIDS).

- Without HIV treatment, this stage may last a decade or longer or may progress faster.

- Stage 3: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS)

-

- The most severe stage of HIV infection.

- Possible high viral load and high likelihood of transmission.

- People with AIDS have badly damaged immune systems. They can get an increasing number of opportunistic infections or other serious illnesses.

- Without HIV treatment, those in Stage 3 (AIDS) typically survive about three years.

Introduction

One of the toughest challenges faced by people living with HIV is social stigma and discrimination. As we go through this course, please imagine a close family member or friend was recently diagnosed with HIV and you are comforting them with this life-changing news. Education is a powerful tool to reduce this stigma, as myths and inaccurate information continue to exist.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How would you describe the unequal impact of HIV?

- Are you familiar with the clinical stages of HIV?

- How would you describe the impact HIV has on the immune system?

- Does HIV always progress to AIDS?

Symptoms

Many patients may be asymptomatic following exposure and infection. The average time from exposure to onset of symptoms is 2 to 4 weeks, although in some cases, it can be as long as 10 months.

A constellation of symptoms, known as an acute retroviral syndrome, may appear acutely. Although none of these symptoms are specific to HIV, their presence of increased severity and duration is an indication of poor prognosis.

These symptoms are listed below (7):

- Fatigue

- Muscle pain

- Skin rash

- Headache

- Sore throat

- Swollen lymph nodes

- Joint pain

- Night sweats

- Diarrhea

Complications

A complication of HIV disease is its progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). AIDS occurs when lymphocyte count falls below a certain level (200 cells per microliters) and is characterized by one or more of the following (7):

- Tuberculosis (TB)

- Cytomegalovirus

- Candidiasis

- Cryptococcal meningitis

- Cryptosporidiosis

- Toxoplasmosis

- Kaposi sarcoma

- Lymphoma

- Neurological complications (AIDS dementia complex)

- Kidney disease

If not treated, HIV can have profound effects on the brain and brain function. Individuals living with HIV should be screened for neurocognitive impairment in a clinical setting, with support for management and neurorehabilitation.

HIV is highly transmissible during acute infection; rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) reduces transmission and early viral suppression to preserve immune function. Essentially, healthcare workers must recognize the significant clinical benefits of early detection for the individual with HIV.

Removing barriers (such as stigmas) to seeking testing and treatment = LIFE

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are examples of complications of HIV?

- How would you explain the importance of early detection to a patient?

- Is reducing the viral load of HIV important in preventing transmission?

- Do you think there is a stigma around requesting HIV testing?

Antiretroviral Therapy (ART)

Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) has transformed the prognosis of HIV from being a condition with declining health that leads to certain death, to a manageable long-term condition, with an expectation of good health and associated quality of life lifespan similar to the non-HIV population.

Clinical Management of HIV

When HIV infection is diagnosed, immediate care is crucial. ART dramatically reduces HIV-related morbidity and mortality, and viral suppression prevents HIV transmission.

The following recommendations support clinical decision-making (6):

- Clinicians should recommend antiretroviral therapy (ART) to all patients diagnosed with acute HIV infection.

- Clinicians should inform patients about the increased risk of transmitting HIV during the acute infection phase and for the 6 months following infection in patients who choose not to begin ART.

- As part of the initial management of patients diagnosed with acute HIV infection, clinicians should:

-

- Consult with a care provider experienced in the treatment of acute HIV infection.

- Obtain HIV genotypic resistance testing for the protease, reverse transcriptase, and integrase genes at the time of diagnosis.

- Patients taking post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP): When acute HIV infection is diagnosed in an individual receiving PEP, ART should be continued pending consultation with an HIV care provider.

- Patients taking pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): The risk of drug-resistant mutations is higher in patients who acquire HIV while taking PrEP, so clinicians should consult with an experienced HIV care provider and recommend a fully active ART regimen.

The clinicians should implement treatment to suppress the patient’s plasma HIV RNA to below-detectable levels (6).

The urgency of ART initiation is even greater in the following individuals:

- Pregnancy

- Acute HIV infection

- 50 years and older

- Presence of advanced disease

For these patients, every effort should be made to initiate ART immediately, ideally on the same

Studies suggest that nearly 25% of all people living with HIV are not accessing antiretroviral therapy. HIV prejudice, unfair stigmas, discrimination, and bias likely correlate with this finding.

Counseling

Communication and interaction immediately following the initial diagnosis of HIV is critical for an ongoing therapeutic relationship. Empathy, compassion, confidentiality, trust, and hope should be paramount. Remember to explain that HIV treatment has dramatically changed the prognosis and future of those living with HIV and emphasize that life can continue very close to the way it did before, while also emphasizing the importance of beginning medication.

A reactive HIV screening result should prompt a care provider to counsel the patient about the benefits and risks of ART and HIV transmission risk, including the consensus that undetectable equals untransmutable (U=U).

Patient education and counseling include:

- Confirming the diagnosis of HIV

- Managing disclosure (if indicated)

- Adhering to the ART regimen

- Communication with the care team to address any potential adverse effects of medications or other concerns

- Clinic visits

- Case management for medications required for lifelong therapy

- In-depth education on ART; including pharmacy selection, insurance requirements and restrictions, copays, and refills.

- Psychosocial support management

- Referring to substance use and behavioral health counseling (if indicated)

- Assessing Health Literacy

-

- National Library of Medicine:

-

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality:

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are patient education topics for an individual who is newly diagnosed with HIV?

- How would you define “health literacy”?

- When is it ideal to begin ART therapy?

- How is the initial interaction and communication important following this diagnosis?

The Devastation of an HIV Diagnosis

Those living with HIV have a completely different story and a very different approach to how they see and think of their HIV status. Several studies have documented and analyzed the psychological impact of an HIV diagnosis. It is meaningful to take a moment and focus on perspectives upon receiving a diagnosis of HIV from actual individuals who have dealt with this experience.

Bella shares, “When I got diagnosed with HIV in March 2008, I was totally devastated and felt that my whole world had been blown apart.”

Jack explains, “Close friends, family, anybody, even new people that I’d meet, I just felt that I couldn’t, I suppose I felt quite, quite worthless because I didn’t have the, [sighs] I felt like I’d lost something, I just found everything so tiring, I didn’t have anything to give, I didn’t feel that I had anything worthwhile to kind of contribute, I don’t know, I was just kind of like shell shocked I suppose.”

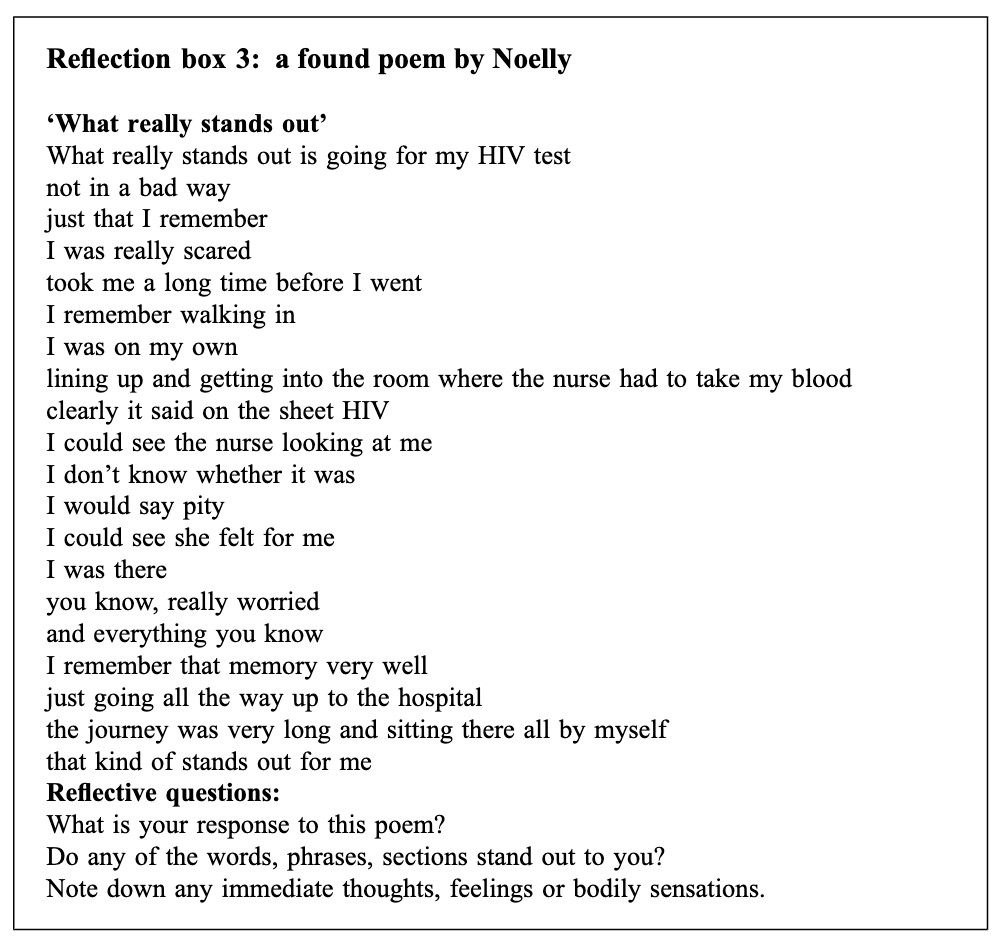

“A found poem” has been constructed from the interview transcript of Noelly:

"What Really Stands Out” poem by Noelly (5)

Themes emerged from the studies. A key theme developed in the analysis of the experience of receiving a diagnosis of HIV was ‘unwelcome and problematic changes in identity.’ Essentially, a separation of their lives into who they were, then following the diagnosis, who they are now (5). These individuals living with HIV often feel they have lost their previous identity and are now defined by this disease.

To compound this devastation, these individuals are further isolated by unfair treatment, discriminatory practices, and bias. Stigmas and discrimination impact patients in their quality of life with HIV through social isolation, stress, emotional coping, and denial of social and economic resources.

HIV-related stigmas are often associated with psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. Furthermore, stigmas in healthcare settings are considered one of the major barriers to optimal treatment for those with HIV or AIDS. Numerous studies suggest that experiences of HIV-related stigmas resulted in lower access to HIV treatment, low utilization of HIV care services, poorer antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence, and thus poorer treatment outcomes (12).

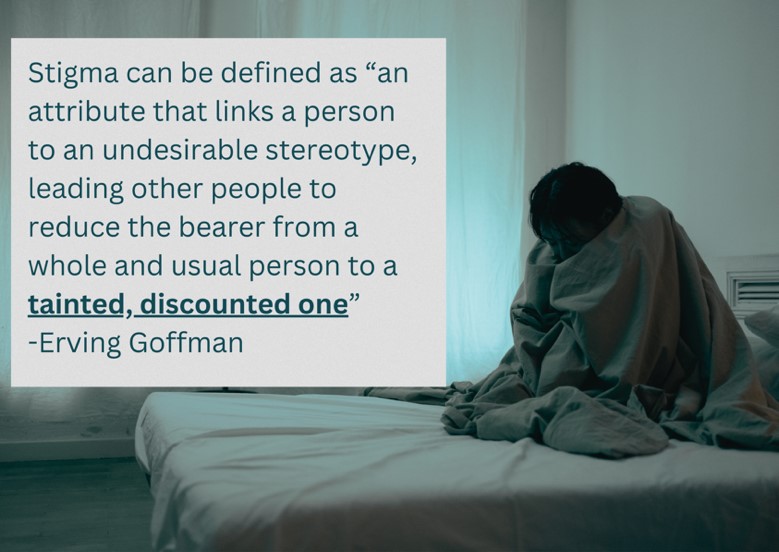

The majority of HIV-related stigma research and theory is based on Goffman’s (1963) work. According to Goffman, stigma can be defined as “an attribute that links a person to an undesirable stereotype, leading other people to reduce the bearer from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one” (12).

Imagine this label of “tainted” or “discounted” was applied to your loved one or yourself. Reflect on the emotions you may experience. Would it be anger, hopelessness, or confusion? Isolation and psychological distress will most likely follow this experience of discrimination.

A helpful model for breaking down the impact of HIV stigma includes the four dimensions:

- Personalized stigma

- Concerns about sharing status

- Negative self-image

- Concern with public attitudes about people with HIV

Stigmas are said to challenge one’s humanity. Stigmas are significantly studied within social psychology. Research has aimed to understand the mechanism by which categories are constructed and linked to stereotyped beliefs, and which stigmas generate and perpetuate health inequities.

A major goal is to dismantle the stigma that continues to be significantly troublesome for people living with HIV today, encouraging proper healthcare access and treatment.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Has there been a time in your own life that you felt different or defined for a reason you did not choose?

- Have you ever been given “life-changing” news?

- In your own words, can you describe “isolation”?

- Can you name various stigmas related to HIV?

Defining Stigma, Discrimination, and Bias

A stigma is an attitude or belief that places a mark of disgrace associated with a particular circumstance, quality, or person (9). HIV stigmas are negative attitudes and beliefs about people who have acquired HIV. The stigma is a prejudice that comes with labeling an individual as part of a group that is believed to be socially unacceptable.

Here are a few examples:

- Believing that only certain groups of people can get HIV.

- Making moral judgments about people who take steps to prevent HIV transmission.

- Feeling that people deserve to get HIV because of their choices.

- Believing that those living with HIV have a morality issue.

Stigmas occur at multiple levels, including interpersonal, institutional (health organizations, schools, committees, and workplaces), community, and legislative levels.

There are different ways in which HIV-related stigmas can manifest. Stigmas have cognitive, affective, and behavioral manifestations. The stigma is associated with a deviation from a constructed ideal or expectation and can often result in the unfair and unjust treatment of an individual based on their HIV status.

The unjust treatment that manifests from a stigma is known as discrimination. Discrimination takes many forms, including isolation, ridicule, and physical and verbal abuse.

Bias occurs when prejudices influence outcomes and decisions (9). This can manifest as denial of services and employment based on HIV status rather than equality or merit.

The mechanism for these processes is based on societal patterns and dominant cultural beliefs in which the undesirable difference is identified and located in an individual or group; these differences amongst people are articulated and labeled as either good or bad. Labeled individuals experience status loss and discrimination that leads to unequal outcomes (e.g. health, economic, social).

Myths about HIV

The spread of myths and false information about HIV must stop for the stigma surrounding HIV to dissipate. The myths have continued to spread regardless of the evidence and research that disproves them. Those in the healthcare field can have a meaningful impact on providing education to all individuals and refute misconceptions.

Myth #1: HIV is a “death sentence”.

Truth: With proper treatment, individuals living with HIV can live a normal life span (11). “Since 1996, with the advent of highly active, antiretroviral therapy, a person with HIV with good access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) can expect to live a normal life span, so long as they take their prescribed medications,” says Dr. Amesh A. Adalja, a board-certified infectious disease physician and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security (10).

Myth #2: HIV can be easily spread by casual contact.

A recent survey found the following inaccurate responses and beliefs about the transmission of HIV:

- It can be transmitted by kissing

- It can be transmitted by spit/saliva

- It is spread only among homosexuals

- It is spread by mosquitoes

- It can be transmitted by toilet seats

- It can be transmitted through urine

- It can be transmitted by sharing utensils, cups, and plates.

Truth: HIV is only transmitted by coming into direct contact with certain body fluids from a person with HIV who has a detectable viral load.

These fluids include:

- Blood

- Semen (cum) and pre-seminal fluid (pre-cum)

- Rectal fluids

- Vaginal fluids

- Breast milk

For transmission to occur, the HIV in those fluids must enter the bloodstream of an HIV-negative person through the following:

- A mucous membrane (rectum, vagina, mouth, or tip of the penis)

- Open cuts or sores

- Direct injection (from a needle or syringe)

Myth #3: If someone has sex with an individual with HIV, the virus will automatically be transmitted.

Truth: Individuals living with HIV who take HIV medication as prescribed and maintain an undetectable viral load will not transmit HIV to their HIV-negative partners.

Myth #4: Those living with HIV cannot safely have children.

Truth: HIV can be transmitted from a mother to her baby during pregnancy, birth, or breastfeeding. This is called perinatal transmission. This is the most common way that children get HIV. However, if a woman with HIV takes the medications as prescribed throughout pregnancy and childbirth and gives HIV medication to her baby for 4 to 6 weeks after birth, the risk of transmission can be less than 1% (4).

Testing all pregnant women for HIV and starting HIV treatment immediately has significantly lowered this occurrence.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How would you respond to someone who believes they can acquire HIV through simply touching someone (no open wounds)?

- How are these irrational fears and myths negatively impacting those living with HIV?

- How can nurses use education to advocate for individuals living with HIV?

- What are some ways to encourage an attitude of hope and life (instead of death and being defined by HIV)?

Forms of Discrimination in Healthcare

Discrimination includes many different actions, attitudes, and behaviors. It is not simply a negative interaction but can come in the form of HIV testing without consent, refusal of care and treatment, and breach of confidentiality. It also comes in the form of irrational self-protection measures that communicate a fear of this person.

Universal Precautions for Care

Imagine how you would feel if every encounter with you, someone applied an unreasonable amount of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) to come near you. Would this make you feel as if they viewed you as “contagious” or “contaminated”? This act is not only unnecessary but also disrespectful and demeaning.

The evidence-based approach recommended is referred to as "universal precautions." Universal precautions are a standard set of guidelines to prevent the transmission of bloodborne pathogens. Blood and body fluid precautions should be consistently used for ALL patients, including those with HIV. Unless a condition or situation requires additional PPE, universal precautions should be followed in the same manner as it would with any patient (3).

Guidelines for Universal Precautions (3):

- All healthcare workers should routinely use appropriate barrier precautions to prevent skin and mucous membrane exposure when in contact with the blood or other body fluids of any patient.

- Gloves should be worn for touching blood and body fluids, mucous membranes, or non-intact skin of all patients, for handling items or surfaces soiled with blood or body fluids, and for performing venipuncture and other vascular access procedures.

- Gloves should be changed after contact with each patient.

- Masks and protective eyewear or face shields should be worn during procedures that are likely to generate blood droplets or other body fluids.

- Gowns or aprons should be worn during procedures that are likely to generate splashes of blood or other body fluids.

- Hands should be washed immediately after gloves are removed.

- Take precautions to prevent injuries caused by needles, scalpels, and other sharp instruments or devices during procedures

- Healthcare workers who have exudative lesions or weeping dermatitis should refrain from all direct patient care and from handling patient care equipment until the condition resolves.

- Isolation precautions should be used as necessary if associated conditions, such as infectious diarrhea or tuberculosis, are diagnosed or suspected.

Breach of Confidentiality

Patients with HIV may mistrust medical providers’ handling of their medical information which is a reason for them not to utilize health services and treatment. Essentially, the fear of compromised confidentiality can lead to becoming reluctant to seek HIV testing and counseling. This impacts the health outcomes of those living with HIV and impacts the community as a whole.

All members of the healthcare team must protect confidential information. Examples of breach of this duty include the following:

- Accessing confidential information, in any form, without a "need to know" to perform assigned duties.

- Leaving confidential information unattended in a non-secure area.

- Disclosing confidential information without proper authorization.

- Discussing confidential information in the presence of individuals who do not have the need to know to perform assigned duties.

- HIV status should never be relayed to anyone who is not directly involved in their care. An example would be if the nurse told another nurse that their patient had HIV, but this nurse was not involved in their care.

- Improper disposal of confidential information.

- Disclosing that a patient or employee is receiving care (except for authorized directory purposes).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What type of PPE or precautions is recommended for the care of those with HIV?

- Have you witnessed breaches of patient confidentiality?

- Should the HIV status of patients be posted on visible areas (documents/outside of the door)?

- How can nurses ensure patient confidentiality among the healthcare team?

Federal and Nevada State Laws Regarding HIV Discrimination

HIV criminalization is a term used to describe laws that criminalize otherwise legal conduct or increase the penalties for illegal conduct based on a person’s HIV-positive status.

HIV criminalization for potential exposure is largely a matter of state law. Federal legislation addresses criminalization in discrete areas, such as blood donation and prostitution. These laws vary as to what behaviors are criminalized or what behaviors result in additional penalties. Several states criminalize one or more behaviors that pose a low or negligible risk for HIV transmission.

In 2021, Nevada reformed their HIV criminal laws to reflect evidence rather than irrational fear.

SB 275 repeals NRS 201.205, which is an HIV-specific criminal offense with a penalty of up to ten years in prison and replaces it with a misdemeanor offense. The misdemeanor offense has the following restrictions:

- Requires intent to transmit, conduct likely to transmit, and actual transmission.

- This applies to the intentional transmission of any communicable disease

- If someone uses means to prevent transmission or if the individual subject to transmission knows the defendant has a communicable disease, knows conduct could result in transmission and consents.

Other changes to Nevada’s law include:

- Repeal of the category-B felony for engaging in or soliciting prostitution after a positive HIV test.

- Repeal of mandatory HIV testing provisions for individuals arrested for prostitution, arrested for a sexual offense, or coming into the custody of the Department of Corrections.

- Amendments to provisions regarding testing for communicable diseases following incidents in which first responders come in contact with bodily fluids.

- Repeal of a provision permitting confinement of persons living with AIDS

- Removal of many stigmatizing references to HIV and AIDS in the public health code.

- Amendments regarding the duties of individuals living with communicable diseases and public health officials’ authority to order testing, treatment, isolation, or quarantine.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Are you familiar with these criminalization laws?

- Can you define HIV criminalization?

- How could the fear of breaches of confidentiality impact an individual seeking healthcare?

- What are some ways that confidentiality could be breached?

Ethical Principles in Healthcare: Autonomy, Beneficence, Non-Maleficence, Justice

Did you know that the nursing profession is the leading trusted profession for honesty and ethics, and has sustained the title for 20 consecutive years (16)? This speaks volumes and should speak to our humanity in the fight to end HIV stigmatization.

Ethical principles should guide nurses to uphold the trust placed upon their shoulders. The topic of nursing ethics is broad, complex, and evolving. The American Nurses Association (ANA) developed a code that serves as a foundation for ethical nursing practice. The code consists of seven ethical obligations and nine provisions that outline the ethical responsibilities of nurses.

7 Ethical Obligations

The 7 ethical obligations within the AMA’s Code of Ethics for Nurses:

- Accountability

- Justice

- Nonmaleficence

- Autonomy

- Beneficence

- Fidelity

- Veracity

Accountability is considered a priority among the ethical principles in nursing. Accountability is when a nurse is responsible for their own choices and actions in the course of patient care. Each nurse is responsible for any inherent bias and cannot place blame on society or cultural norms.

Justice refers to fair and impartial care, as treating each patient fairly, regardless of their circumstances, is essential to better patient outcomes.

The following factors should never result in partiality or lower standards of care:

- HIV Status

- Age

- Race

- Sexual orientation

- Ethnicity

- Religion

- Socioeconomic status

9 Ethical Provisions

These provisions can individually apply to the treatment of those living with HIV:

| American Nurses Association (ANA) Code of Ethics for Nurses: 9 Ethical Provisions | |

| Provision 1 | “The nurse practices with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person.” |

| Provision 2 | “The nurse's primary commitment is to the patient, whether an individual, family, group, community, or population.” |

| Provision 3 | “The nurse promotes, advocates for, and protects the rights, health, and safety of the patient.” |

| Provision 4 | “The nurse has authority, accountability, and responsibility for nursing practice; makes decisions; and takes action consistent with the obligation to promote health and to provide optimal care.” |

| Provision 5 | “The nurse owes the same duties to self as to others, including the responsibility to promote health and safety, preserve wholeness of character and integrity, maintain competence, and continue personal and professional growth.” |

| Provision 6 | “The nurse, through individual and collective efforts, establishes, maintains, and improves the ethical environment of the work setting and conditions of employment that are conducive to safe, quality health care.” |

| Provision 7 | “The nurse, in all roles and settings, advances the profession through research and scholarly inquiry, professional standards development, and the generation of both nursing and health policy.” |

| Provision 8 | “The nurse collaborates with other health professionals and the public to protect human rights, promote health diplomacy, and reduce health disparities.” |

| Provision 9 | “The profession of nursing, collectively through its professional organizations, must articulate nursing values, maintain the integrity of the profession, and integrate principles of social justice into nursing and health policy.” |

|

Resource: American Nurses Association. (2019). Code of ethics with interpretative statements. Silver Spring, MD. |

|

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Are you familiar with the ANA’s Code of Ethics?

- How can these provisions apply to caring for those living with HIV?

- How can these principles be expanded into community involvement and advocacy?

- How would you define “justice”?

Reducing Stigmas and Discrimination

At this point in the course, we invite you to reflect on your own experiences and recognize any bias toward those with HIV. We will apply a technique from cognitive behavioral therapy, identify a thought or concept, challenge its truthfulness, and then dismantle false conceptions.

Education and Training

Healthcare employees, HIV prevention researchers, and service providers should receive formal education in their academic programs and their workplaces to learn how implicit bias influences the practice of medicine and impacts outcomes. Training should effectively develop skills to reduce negative behaviors and mitigate negative outcomes associated with these biases. Institutions and organizations should also develop and implement initiatives to identify disparities and inequities in their services and practices.

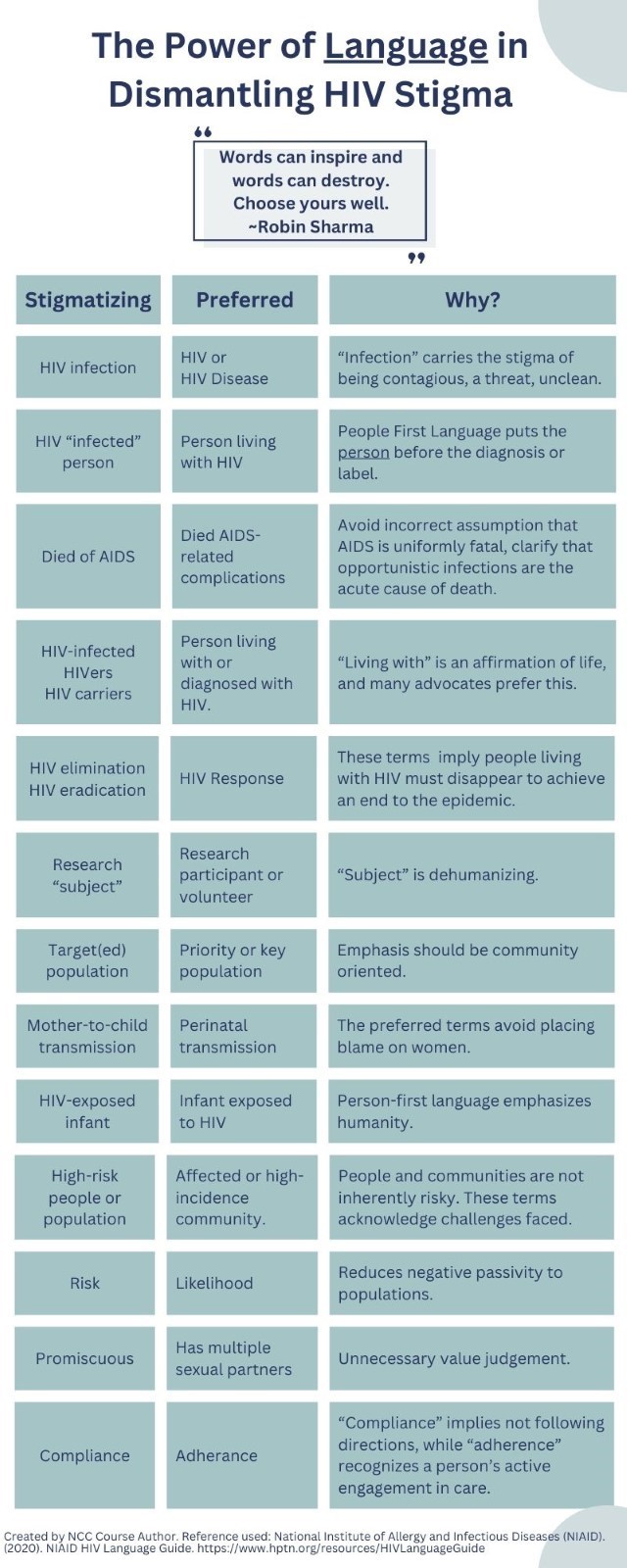

The Power of Language

Language has been a central theme in efforts to dismantle the stigma around HIV (8). When healthcare providers write or speak about HIV, the words they choose have the power to passively maintain ignorance and bias. However, they also have the power to convey respectful and accurate representations and perspectives on those living with this condition.

You may be inadvertently using stigmatizing language, so it is imperative to recognize this harmful language, stop using it, and join in the effort to reduce its use by others.

Let's Talk about it!

Speaking about HIV should not be taboo. The more a topic is discussed, the more it becomes normalized. Talking openly about HIV provides opportunities to correct misconceptions and help others learn more about HIV. Remember to be mindful of how you talk about HIV and people living with HIV. Discussions can be in-person or online; locations can include family, friends, support group members, workplace interactions, social media, and blogs. Get comfortable with saying things like “I was HIV tested and it was a very simple process”.

Educating children and young people to understand how stigmas are formed and operate can help dismantle the continuation of stigmas surrounding HIV.

The Power of Community

Studies show that individuals with strong social support are less likely to feel stigmatized than those who are isolated. If you notice someone is uncomfortable seeking comfort from friends and family, encourage them to contact their local public health department to find HIV support groups within the community.

The HIV Prevention Trials Network developed the LOC Community Engagement Program (CEP) which supports community advisory structures such as Community Working Groups (CWGs) and site Community Advisory Boards (CABs) to represent the participant community. These groups can raise research-related issues or concerns that may impact the participants, community, or study.

Using a cognitive behavioral therapy approach to understand relationships between thoughts, feelings, physical responses, and coping behaviors can be helpful.

Promoting individual-level coping skills and group-based social support focused on the following:

- Decreasing negative feelings toward self and others living with HIV

- Increasing planned and strategic HIV sharing with others and building supportive

- Networks to reduce fears and feelings of rejection

- Building skills to address HIV-related discrimination and other forms of stigma.

Advocacy and Policy

Reducing the stigma associated with HIV is critical for improving public health outcomes, encouraging individuals to seek testing and treatment, and supporting those living with HIV. An interprofessional approach can lead to meaningful change.

Early access to treatment and adherence to the treatment regimen reduces susceptibility to opportunistic infection associated with AIDS and increases life expectancy. To maintain this, clinical treatment guidelines that outline compassionate and unbiased delivery modes of health, treatment, and psychosocial support are required. Healthcare workers play a vital role in this process.

Here are some effective strategies that healthcare workers can use to reduce HIV stigmas:

- Education to Counter Myths and Misconceptions

- Provide accurate information to patients, communities, and even colleagues about HIV transmission, prevention, and the reality that an HIV diagnosis is a manageable health condition.

- Debunk Myths: Actively challenge myths and misconceptions about how HIV is transmitted. Clarify that it cannot be spread by casual contact such as shaking hands, sharing dishes, or hugging.

- Empathy and Nonjudgmental Care

- Show Genuine Empathy: Use supportive and empathetic communication, which is essential for making patients feel valued and understood.

- Avoid Judgment: Practice nonjudgmental care and treat all patients with the same level of compassion and professionalism, regardless of their HIV status.

- Confidentiality and Privacy

- Ensure Confidentiality: Strictly adhering to confidentiality laws and regulations regarding privacy will build trust and encourage patients to seek and continue treatment.

- Respect Privacy: Discuss sensitive information privately and discreetly to prevent inadvertent disclosure.

- Encourage Inclusive Language

- Use Appropriate Language: Employ language that is respectful and free from stigmas.

- Correct Stigmatizing Language: Gently correct peers and patients when they use stigmatizing language, explaining why it is considered harmful.

- Visibility and Public Advocacy

- Promote Positive Representation: Support and promote stories and data that highlight the normal and productive lives that people with HIV lead.

- Engage in Advocacy: Participate in public speaking, media interviews, or social media campaigns to advocate for people living with HIV and to educate the public.

- Professional Development and Training

- Engage in regular training on the latest HIV research, treatments, and approaches to care that emphasize dignity and respect.

- Cultural Competence: Train in cultural competency to better understand and address the diverse backgrounds and experiences of patients with HIV.

- Support Networks and Resources

- Provide Resources: Offer information about local support groups and other resources that may help individuals with HIV feel supported and less isolated.

- Encourage Social Support: Promote engagement with community networks which can provide practical and emotional support.

- Integrate HIV care with other health services to normalize treatment and reduce the isolation of HIV-specific services.

- Peer Involvement: Include peer counselors who are living with HIV in the care team to provide relatable experiences and hope.

By adopting these strategies, healthcare workers can significantly reduce the stigma surrounding HIV and improve both the mental and physical health outcomes for people living with HIV. This not only helps in managing the disease but also integrates support for individuals into everyday life, promoting a more inclusive and compassionate healthcare environment.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Why should using the statement “HIV infected” be avoided?

- What are some terms that would be stigmatizing for those living with HIV?

- How can you become involved in reducing and eradicating the HIV stigma?

- How can reducing this stigma lead to better health outcomes?

Conclusion

As we conclude our exploration of discrimination in the context of HIV/AIDS, we reflect on the profound lessons learned and the pressing challenges that remain. Throughout this course, we have examined the multifaceted nature of stigmas and discrimination—its roots, its manifestations, and the devastating impact on individuals and communities. Discrimination against people living with HIV/AIDS is not only a violation of human rights but also a significant barrier to effective HIV prevention, treatment, and care.

Through education, advocacy, and policy change, we can challenge misconceptions, change negative behaviors, and foster an environment where all individuals, regardless of their HIV status, are treated with dignity and respect. Let us take forward the call to action to advocate for inclusive policies, promote HIV awareness, and support the ongoing fight against the stigma.

References + Disclaimer

- American Academy of HIV Medicine (AAHIVM). Retrieved from: https://aahivm.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/cdc-pic-facts-and-fiction.pdf

- Andrasik, M., Broder, G., Oseso, L., Wallace, S., Rentas, F., & Corey, L. (2020). Stigma, Implicit Bias, and Long-Lasting Prevention Interventions to End the Domestic HIV/AIDS Epidemic. American journal of public health, 110(1), 67–68. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305454

- Broussard IM, Kahwaji CI. Universal Precautions. [Updated 2023 Jul 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470223/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2021). About HIV. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/whatishiv.html

- Croston, M., & Rutter, S. (Eds.). (2020). Psychological perspectives in HIV care : an inter-professional approach. Routledge.

- Cowan EA, McGowan JP, Fine SM, et al. (2021). Diagnosis and Management of Acute HIV Baltimore (MD): Johns Hopkins University; 2021 Jul. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563020/

- Justiz Vaillant, A.A., Gulick P.G. (2022). HIV and AIDS Syndrome. In: Stat Pearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534860/

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). (2020). NIAID HIV Language Guide. Retrieved from https://www.hptn.org/resources/HIVLanguageGuide.

- Oxford University Press. (n.d.) Stigma. In Oxford English dictionary. Retrieved from https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/acref/9780199534067.001.0001/acref-9780199534067-e-9263#:~:text=A%20mark%20of%20disgrace%20associated,mark%20on%20the%20skin%20.

- Schaefer, A. (2020). 9 Myths about HIV/ AIDS. Healthline. Retrieved from https://www.healthline.com/health/hiv-aids/misconceptions-about-hiv-aids

- Smallwood, S. W., & Parks, F. M. (2023). The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same: HIV/AIDS Myths and Misinformation in the Rural United States. Health Promotion Practice., 15248399231180592–15248399231180592. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248399231180592

- Tran, B. X., Phan, H. T., Latkin, C. A., Nguyen, H. L. T., Hoang, C. L., Ho, C. S. H., & Ho, R. C. M. (2019). Understanding Global HIV Stigma and Discrimination: Are Contextual Factors Sufficiently Studied? (GAPRESEARCH). International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(11), 1899. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16111899

- Watson, S., Namiba, A., & Lynn, V. (2019). The language of HIV: a guide for nurses. HIV Nursing 2019; 19(2).

- Williams Institute. (2021). Enforcement of Enforcement of HIV Criminalization in Nevada. UCLA. Retrieved from https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/hiv-criminalization-nevada/.

- UnAids. (2023). Global HIV & AIDS statistics — Fact sheet. Retrieved from https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet#:~:text=Global%20HIV%20statistics,AIDS%2Drelated%20illnesses%20in%202022.

- Saad, L. (2022). Military brass, judges among professions at new image lows. Gallup, Inc. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/388649/military-brass-judges-among-professions-new-image-lows.aspx

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate