Course

New Jersey Implicit and Explicit Bias

Course Highlights

- In this New Jersey Implicit and Explicit Bias course, we will learn about how implicit and explicit biases related to race, socioeconomic status, weight, age, and sexual orientation impact pain management, patient communication, and treatment decisions in obstetrics and gynecology.

- You’ll also learn the historical and systemic factors that contribute to persistent stereotypes and biases in maternity care, and assess their influence on modern healthcare tools, protocols, and provider behaviors.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of practical strategies grounded in antiracism and social justice to recognize and address biases, including implementing bias awareness training, curriculum redesign, and organizational policy changes to promote equitable, person-centered maternity care for all pregnant persons.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 1

Course By:

R.E. Hengsterman MSN, RN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

In OB-GYN care, biases—both implicit and explicit—can affect pain management during labor, the interpretation of patient concerns, and treatment decisions based on factors such as race, ethnicity, weight, age, or sexual orientation [1]. These biases contribute to disparities in care and can result in negative health outcomes [1]. Implicit bias stems from unconscious stereotypes, while explicit bias involves expressed discriminatory attitudes [2].

The presence of both explicit and implicit biases among maternity care providers plays a significant role in creating disparities in person-centered maternity care (PCMC) [3]. These biases can influence providers' perceptions and behaviors, leading to unequal treatment of pregnant persons during childbirth. Individuals of lower socioeconomic status (SES) often experience less dignified, less responsive care compared to those of higher SES, perpetuating healthcare inequalities [4]. Understanding the impact of these biases is crucial for addressing disparities in PCMC and ensuring that all pregnant persons receive respectful, responsive care regardless of their socioeconomic background. Implicit bias often leads to associating high socioeconomic status (SES) with positive patient traits and low SES with negative ones, contributing to inequities in the quality of care provided [5].

PCMC, defined as respectful and responsive care that honors the preferences, needs, and values of pregnant person during childbirth, has gained prominence in global health discussions [6]. Despite this focus, PCMC remains suboptimal, with significant disparities based on SES. Pregnant persons of lower SES tend to experience poorer PCMC, characterized by less dignified treatment, ineffective communication, and diminished respect for autonomy, compared to pregnant person of higher SES [7]. Disrespectful and non-responsive care, common in facility-based childbirth, deters pregnant persons from seeking institutional care, which can affect maternal and neonatal health outcomes.

Positive PCMC experiences lead to improved outcomes, including increased patient engagement, trust, satisfaction, and stronger psychosocial health [8]. Studies have demonstrated that essential components of PCMC, including birth companionship and respectful communication, are associated with favorable clinical outcomes like shorter labor duration and lower rates of cesarean deliveries [9]. Disrespectful treatment and assumptions about the cognitive abilities or cooperation of low SES pregnant person perpetuate negative healthcare experiences and reinforce community mistrust of facility-based childbirth services [3].

Both explicit and implicit biases shape these care disparities. Explicit bias reflects conscious negative attitudes or beliefs toward certain groups [2]. Implicit bias influences behavior through quick, automatic associations triggered by characteristics like appearance or SES [2].

While much of the research on healthcare provider bias has focused on racial disparities, SES bias is relevant in contexts where racial distinctions are less pronounced. In the United States, many perceive low-SES patients as less intelligent, compliant, or engaged in their health, leading to poorer care, shorter consultations, and fewer diagnostic tests [4][10]. Patients report feeling the impact of SES bias through perceived discrimination and lower quality interactions with healthcare professionals, contributing to mistrust and poorer health outcomes over time [1][4].

These outcomes emphasize the need to address both forms of bias through targeted interventions aimed at improving PCMC is those with a lower SES. Improving provider awareness and enhancing communication, respect, and responsiveness in care delivery are critical steps in reducing disparities and improving health outcomes for all pregnant persons [11].

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How might implicit and explicit biases influence the perceptions and behaviors of maternity care providers toward pregnant persons of different socioeconomic statuses?

- In what ways can biases based on socioeconomic status contribute to disparities in person-centered maternity care and affect maternal and neonatal health outcomes?

- Why is it important to address both implicit and explicit biases when aiming to improve respectful and responsive care for all pregnant persons?

- How can understanding the role of socioeconomic status in healthcare biases help in developing interventions to reduce disparities in maternity care?

Bias and Stereotyping in Healthcare

Unscientific beliefs that attribute racial health disparities to biological or genetic differences, rather than to racism, remain pervasive in medical education and practice [12]. These misconceptions, often left unchallenged at the institutional level, infiltrates treatment decisions involving race, and this harms outcomes. For instance, medical students and residents who held explicit stereotypes about Black individuals being of biological difference made less accurate pain management decisions for Black patients [13].

Within the field of obstetrics and gynecology there are significant and perpetuating such stereotypes. The unethical experiments conducted by early gynecologists like J. Marion Sims and François Marie Prevost on enslaved women, including Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsy, while resulting in advances such as vesicovaginal fistula repair and cesarean delivery, contributed to harmful racial stereotypes [14]. These experiments fostered the false belief that Black pregnant persons have a higher tolerance for pain, a stereotype that persists today and may explain why Black pregnant persons may receive epidural analgesia at a reduced rate during labor or postpartum opioids, even when pain levels are comparable [14].

This belief continues to influence modern obstetric tools and decision-making processes. The Vaginal Birth After Cesarean (VBAC) success calculator is a tool to estimate the likelihood of a successful vaginal delivery after a previous cesarean section [15]. The calculator incorporates several factors, including maternal age, body mass index (BMI), prior vaginal delivery, and notably, race or ethnicity. As a result, well-meaning clinicians practicing evidence-based medicine may provide differing counseling to White and Black patients. For instance, the calculator might predict a 66.1% chance of successful VBAC for a White woman but only 49.9% for a Black woman with identical clinical characteristics [12]. This race-based counseling can lead to different decisions—where a White woman may pursue a trial of labor, a Black woman may opt for cesarean delivery, thus contributing to unnecessary maternal morbidity and exacerbating racial disparities in healthcare.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What might be the underlying reasons that unscientific beliefs attributing racial health disparities to biological differences persist in medical education and practice?

- In what ways have historical unethical medical practices on enslaved women influenced current stereotypes and treatment approaches in obstetrics and gynecology?

- How does the use of race or ethnicity in tools like the VBAC success calculator affect clinical counseling, and what are the potential implications for racial disparities in healthcare outcomes?

Transformations in Care Delivery

The use of standardized protocols can enhance outcomes and address disparities [16]. In California, hospitals implemented a hemorrhage quality improvement collaborative that reduced Black–White disparities in severe maternal morbidity [17]. A labor induction protocol reduced racial disparities in cesarean deliveries and neonatal morbidity [28]. However, standardized protocols may also contribute to disparities. A California hospital implemented a prenatal substance use reporting protocol to child protective services, causing reports of Black mothers to occur five times more often than reports of White mothers during the study period [12]. This outcome resulted from the policy. Standardized quality improvement protocols can worsen disparities across care settings because health systems serving vulnerable populations lack sufficient resources to implement these initiatives [29].

It is important to invest in initiatives aimed at reducing Black–White maternal health disparities and to pilot test them before wide-scale implementation to prevent exacerbating inequalities. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' support of the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act of 2021 shows how medical professionals can direct resources to underfunded healthcare systems that serve Black women, ensuring they have the necessary tools to implement and monitor quality improvements [18].

Furthermore, patients of all backgrounds should receive care based on clinical guidelines supported by reliable data. Such care can reduce or even eliminate racial disparities in certain health outcomes, as seen in ovarian cancer survival rates [19]. The Research Working Group of the Black Mamas Matter Alliance developed a research framework to ensure that Black pregnant persons participate in research teams and studies [20].

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How might standardized protocols both reduce and contribute to healthcare disparities in maternal health?

- What factors and practices prevent standardized initiatives from exacerbating inequalities in vulnerable populations?

- Why is it important to pilot test health interventions before implementing them on a wide scale, especially concerning racial disparities?

- How does involving Black pregnant persons in research teams and studies contribute to more equitable healthcare outcomes?

Framework for Addressing Implicit and Explicit Bias in Maternity Care

Curriculum Design with Antiracism and Social Justice Foundations

Develop an educational framework rooted in antiracism and social justice theories. This equips learners to recognize and challenge practices within the field of care.

Bias Awareness and Management Training

Incorporate training on recognizing and managing bias throughout the curriculum. This training should focus on both implicit and explicit biases, helping healthcare providers understand their impact on patient care and outcomes.

Removal of Stereotypical Patient Descriptions

Eliminate stereotypical patient descriptions from all syllabi, case studies, and examination materials. This prevents the reinforcement of harmful biases in the learning environment and promotes equitable care for all patients.

Critical Analysis of Epidemiology and Evidence-Based Medicine

Encourage critical review of epidemiology and evidence-based medicine to identify and address assumptions rooted in discriminatory practices or structural racism. This ensures that medical knowledge does not unintentionally perpetuate stereotypes and biases.

Competency-Based Education and Holistic Evaluations

Adopt competency-based medical education and holistic evaluation methods to reduce bias in the assessment of learners. This approach emphasizes skills and knowledge over factors that bias may influence, promoting fairness in evaluation and advancement.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How can integrating antiracism and social justice theories into medical education help learners recognize and challenge existing practices in healthcare?

- What effects might removing stereotypical patient descriptions from educational materials have on the delivery of equitable patient care?

Strategies for Addressing Implicit Bias in Healthcare

To address health inequities, many U.S. states have considered or enacted laws requiring implicit bias training (IBT) for healthcare providers. California's "Dignity in Pregnancy and Childbirth Act" mandates that hospitals and birth centers offer IBT to perinatal clinicians to improve outcomes for Black pregnant persons and birthing people [21]. Gathering insights from IBT stakeholders is essential for shaping policy, developing curricula, and guiding implementation efforts.

Education on implicit bias and strategies for managing its impact should be a core component of broader health system efforts to standardize knowledge on recognizing and addressing bias. Research conducted by the Center for Health Workforce Studies at the University of Washington School of Medicine evaluated the effectiveness of a brief online course on implicit bias in clinical and educational settings. The study found that the course increased bias awareness among a national sample of academic clinicians, regardless of their personal characteristics, practice setting, or the level of their implicit racial and gender-based biases [22].

Public policy plays a key role in addressing bias in medical care and promoting racial diversity in the perinatal workforce. The federal government also plays a crucial role in addressing discrimination in healthcare. The Office of Civil Rights conducts Title VI investigations into allegations of discrimination within organizations receiving funding [23]. Legal and healthcare experts have suggested reforms to Title VI to extend these investigations to include all physician-provided services. This helps increase trust among patients, promotes diligence among physicians, and works to reduce disparities in treatment.

Beyond raising awareness, clinicians can take concrete steps to manage the impact of implicit bias in patient care. Act by engaging in role modeling; participate in training to address and interrupt microaggressions and behaviors; and undergo training to eliminate descriptions in notes and communications. Teaching faculty at academic medical centers can contribute by developing inclusive curricular materials that feature diverse imagery and examples, and by consistently using inclusive language in all forms of communication.

At the organizational level, the foundation of bias-management efforts should be a comprehensive, ongoing diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) education program [24]. This program should focus on interactive, skill-building education that addresses implicit bias recognition and management and should involve all employees and trainees across the healthcare system. Organizations should also collect data to track equity and monitor progress and adopt best practices for increasing workforce diversity and integrate antibias education and practices into their professionalism policies. Policies for hiring, performance review, and promotion should also give weight to candidates’ DEI contributions.

Reporting systems can further institutional efforts to manage bias. Incident-response teams can review incidents, gather information, and either refer the matter to a department, such as human resources, or conduct further investigation. Transparency is key to the process, and reporting on bias incidents, detailing affected groups, locations, and common themes. The four high-priority areas for intervention: bias in pain management, responses to microaggressions and implicit bias, biased behaviors from patients toward medical staff, and opportunities for enhancing institutional inclusivity [25]. By implementing similar strategies, both individuals and organizations can take meaningful steps toward reducing bias and promoting equity in healthcare settings.

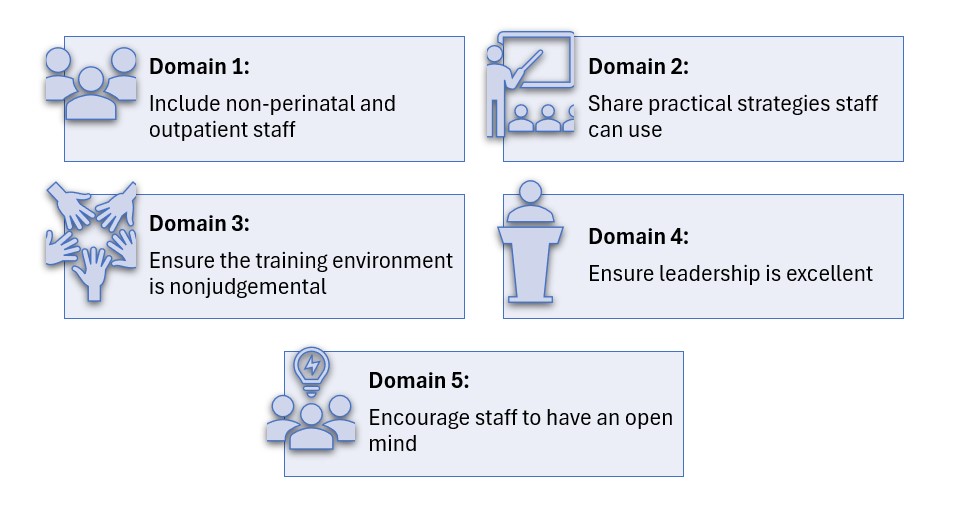

Implicit Bias Training (IBT) is a vital tool for reducing disparities in healthcare and improving patient outcomes in maternity care [26]. Effective IBT helps healthcare providers recognize and address their unconscious biases, leading to more equitable and compassionate care. The following domains outline key areas for enhancing IBT, offering practical strategies for its expansion, effectiveness, implementation, cultural integration within healthcare facilities, and fostering provider engagement.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How does mandatory implicit bias training, as required by laws like California's "Dignity in Pregnancy and Childbirth Act," impact the outcomes for Black pregnant persons and birthing people?

- Why is it crucial for healthcare providers to engage in education on implicit bias, and what effects might this have on their clinical practice and patient interactions?

- In what ways can public policy and federal initiatives, such as Title VI investigations, play a role in addressing discrimination and promoting diversity within the healthcare system?

- How can healthcare organizations implement comprehensive strategies—including diversity, equity, and inclusion programs and transparent reporting systems to manage and reduce implicit bias among clinicians and staff?

Implicit Bias Training Domains

Domain 1: Scope and Requirements of Implicit Bias Training (IBT)

Instructive Summary: To improve IBT, expand the scope to include non-perinatal and outpatient healthcare providers. Set clear guidelines on training frequency and duration, and establish accountability measures, such as penalties and standards linked to bias performance.

Domain 2: Effectiveness and Structure of IBT

Instructive Summary: For IBT to be effective, it must address systemic biases and provide practical strategies for clinicians. Use real patient stories and case studies to foster reflection and offer actionable insights for managing bias in clinical situations.

Domain 3: Implementing IBT in Healthcare Settings

Instructive Summary: Ensure successful IBT implementation by selecting credible trainers, including community members where possible, and creating safe, nonjudgmental training environments. Provide protected time, continuing education credits, and use data to assess the training's impact on clinical outcomes.

Domain 4: Healthcare Facility Culture and IBT

Instructive Summary: Leadership must demonstrate commitment to reducing bias, fostering trust, and encouraging open dialogue among staff. Implement accountability measures, such as tracking IBT participation and monitoring care quality, to ensure progress in addressing bias.

Domain 5: Provider Engagement and IBT

Instructive Summary: Providers must approach IBT with an open mind and work to recognize their own biases. Focus on engagement to prevent reactions, while understanding that even changes in behavior can improve outcomes.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How could expanding implicit bias training to include non-perinatal and outpatient providers, along with clear guidelines and accountability measures, impact the overall quality of healthcare delivery?

- In what ways might the commitment of healthcare leadership and the engagement of providers influence the success of implicit bias training in reducing disparities and improving patient outcomes?

- How do both conscious and unconscious biases among healthcare providers contribute to disparities in OB-GYN care affect treatment and outcomes for patients from lower socioeconomic backgrounds?

Conclusion

Biases contribute to disparities in healthcare [27]. Biases include attitudes and assumptions individuals recognize and report, leading to actions based on race, gender, and sexual orientation. Other biases involve attitudes related to characteristics like race, ethnicity, age, and gender, influencing judgments and behaviors without awareness. These biases operate within systems like racism and sexism, affecting patient care, medical training, workforce diversity, and career advancement [25]. Addressing both types of bias is important for achieving equity and improving outcomes.

In OB-GYN care, biases around factors like race, socioeconomic status (SES), weight, and sexual orientation impact pain management, interpretation of patient concerns, and treatment decisions. Individuals from lower SES backgrounds often receive less care, reinforcing inequalities [1]. Providers may associate high SES with certain traits and low SES with others, affecting the quality of care they provide [4]. This occurs in maternity care, where biases can lead to issues in treatment, communication, and autonomy for patients from lower SES backgrounds, affecting health outcomes [4]. Interventions that address these biases, empower patients, and hold providers accountable are important for improving maternal care and reducing disparities in outcomes.

References + Disclaimer

- Gopal, D. P., Chetty, U., O’Donnell, P., Gajria, C., & Blackadder-Weinstein, J. (2021). Implicit bias in healthcare: clinical practice, research and decision making. Future Healthcare Journal, 8(1), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.7861/fhj.2020-0233

- Shah, H. S., & Bohlen, J. (2023, March 4). Implicit bias. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK589697/

- Afulani, P. A., Okiring, J., Aborigo, R. A., Nutor, J. J., Kuwolamo, I., Dorzie, J. B. K., Semko, S., Okonofua, J. A., & Mendes, W. B. (2023). Provider implicit and explicit bias in person-centered maternity care: a cross-sectional study with maternity providers in Northern Ghana. BMC Health Services Research, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09261-6

- McMaughan, D. J., Oloruntoba, O., & Smith, M. L. (2020). Socioeconomic status and access to healthcare: interrelated drivers for healthy aging. Frontiers in Public Health, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00231

- Job, C., Adenipekun, B., Cleves, A., & Samuriwo, R. (2022). Health professional’s implicit bias of adult patients with low socioeconomic status (SES) and its effects on clinical decision-making: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open, 12(12), e059837. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059837

- Tarekegne, A. A., Giru, B. W., & Mekonnen, B. (2022). Person-centered maternity care during childbirth and associated factors at selected public hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2021: a cross-sectional study. Reproductive Health, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-022-01503-w

- Afulani, P. A., Sayi, T. S., & Montagu, D. (2018). Predictors of person-centered maternity care: the role of socioeconomic status, empowerment, and facility type. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3183-x

- Afulani, P. A., Oboke, E. N., Ogolla, B. A., Getahun, M., Kinyua, J., Oluoch, I., Odour, J., & Ongeri, L. (2022). Caring for providers to improve patient experience (CPIPE): intervention development process. Global Health Action, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2022.2147289

- Dubey, K., Sharma, N., Chawla, D., Khaduja, R., & Jain, S. (2023). Impact of birth companionship on maternal and fetal outcomes in primigravida pregnant personin a government tertiary care center. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.38497

- Arpey, N. C., Gaglioti, A. H., & Rosenbaum, M. E. (2017). How socioeconomic status affects patient perceptions of health care: a Qualitative study. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 8(3), 169–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150131917697439

- Kwame, A., & Petrucka, P. M. (2021). A literature-based study of patient-centered care and communication in nurse-patient interactions: barriers, facilitators, and the way forward. BMC Nursing, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00684-2

- Green, T. L., Zapata, J. Y., Brown, H. W., & Hagiwara, N. (2021). Rethinking bias to achieve maternal health equity. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 137(5), 935–940. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000004363

- Meints, S. M., Cortes, A., Morais, C. A., & Edwards, R. R. (2019). Racial and ethnic differences in the experience and treatment of noncancer pain. Pain Management, 9(3), 317–334. https://doi.org/10.2217/pmt-2018-0030

- Reproductive medicine advances linked to slavery. (2022, March 31). NIH Record. https://nihrecord.nih.gov/2022/04/01/reproductive-medicine-advances-linked-slavery

- Thornton, P. D., Liese, K., Adlam, K., Erbe, K., & McFarlin, B. L. (2020). Calculators estimating the likelihood of vaginal birth after cesarean: Uses and perceptions. Journal of Midwifery & Pregnant Women’s Health, 65(5), 621–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.13141

- Zhang, X., Hailu, B., Tabor, D. C., Gold, R., Sayre, M. H., Sim, I., Jean-Francois, B., Casnoff, C. A., Cullen, T., Thomas, V. A., Artiles, L., Williams, K., Le, P., Aklin, C. F., & James, R. (2019). Role of health information Technology in addressing health disparities. Medical Care, 57(Suppl 2), S115–S120. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000001092

- Main, E. K., Chang, S., Dhurjati, R., Cape, V., Profit, J., & Gould, J. B. (2020). Reduction in racial disparities in severe maternal morbidity from hemorrhage in a large-scale quality improvement collaborative. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 223(1), 123.e1-123.e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.01.026

- The Momnibus Act | Black Maternal Health Caucus. (2024, July 8). Black Maternal Health Caucus. https://blackmaternalhealthcaucus-underwood.house.gov/Momnibus

- Mei, S., Chelmow, D., Gecsi, K., Barkley, J., Barrows, E., Brooks, R., Huber-Keener, K., Jeudy, M., O’Hara, J. S., & Burke, W. (2023). Health disparities in ovarian cancer. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 142(1), 196–210. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000005210

- Black Pregnant personScholars and the Research Working Group of the Black Mamas Matter Alliance, Aina, A. D., Asiodu, I. V., Castillo, P., Denson, J., Drayton, C., Aka-James, R., Mahdi, I. K., Mitchell, N., Bella Morgan, I., Robinson, A., Scott, K., Williams, C. R., Aiyepola, A., Arega, H., Chambers, B. D., Crear-Perry, J., Delgado, A., Doll, K., . . . Wolfe, T. (2020). Black Maternal Health Research Re-Envisioned: Best Practices for the conduct of research with, for, and by Black mamas. In Harvard Law & Policy Review (Vol. 14, pp. 394–415). https://journals.law.harvard.edu/lpr/wp-content/uploads/sites/89/2020/11/BMMA-Research-Working-Group.pdf

- California Preterm Birth Initiative. (2019). Policy Report: Legal analysis, stakeholder insights, & policy recommendations for healthcare provider implicit bias training in California. In California Preterm Birth Initiative. https://pretermbirthca.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra2851/f/MEND%20Policy%20Report_Final20231118.pdf

- Sabin, J., Guenther, G., Ornelas, I. J., Patterson, D. G., Andrilla, C. H. A., Morales, L., Gujral, K., & Frogner, B. K. (2022). Brief online implicit bias education increases bias awareness among clinical teaching faculty. Medical Education Online, 27(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2021.2025307

- Section V – Defining Title VI. (2021, February 3). https://www.justice.gov/crt/fcs/T6manual5

- Lingras, K. A., Alexander, M. E., & Vrieze, D. M. (2021). Diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts at a departmental level: building a committee as a vehicle for advancing progress. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 30(2), 356–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-021-09809-w

- Sabin, J. A. (2022). Tackling implicit bias in health care. New England Journal of Medicine, 387(2), 105–107. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2201180

- Garrett, S. B., Jones, L., Montague, A., Fa-Yusuf, H., Harris-Taylor, J., Powell, B., Chan, E., Zamarripa, S., Hooper, S., & Butcher, B. D. C. (2023). Challenges and Opportunities for Clinician Implicit Bias Training: Insights from Perinatal Care Stakeholders. Health Equity, 7(1), 506–519. https://doi.org/10.1089/heq.2023.0126

- Vela, M. B., Erondu, A. I., Smith, N. A., Peek, M. E., Woodruff, J. N., & Chin, M. H. (2022). Eliminating explicit and implicit biases in health care: evidence and research needs. Annual Review of Public Health, 43(1), 477–501. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-052620-103528

- Hamm, R. F., Srinivas, S. K., & Levine, L. D. (2020). A standardized labor induction protocol: impact on racial disparities in obstetrical outcomes. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM, 2(3), 100148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100148

- Hughes, R. G. (2008, April 1). Tools and strategies for quality improvement and patient safety. Patient Safety and Quality – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2682/

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate