Course

New York Mandatory Prescriber Education

Course Highlights

- In this course we will learn about pain management, and why it is important for Advance Practice Registered Nurses.

- You’ll also learn the basics of pain assessment and controlled substance prescribing, as required by the New York Board of Nursing.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of opioids and pain management.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 3

Course By:

Abbie Schmitt

MSN-Ed, RN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

Introduction

Welcome to the transformative journey to enhance your prescribing practices, safeguard your patients, and be a catalyst for positive change in the fight against opioid addiction in New York State. As healthcare providers, it is vital to be equipped with the latest knowledge and skills for safe and effective prescribing of controlled substances, ultimately contributing to the reduction of opioid misuse and improving patient care outcomes in New York State. Familiarity with state and federal regulation of controlled substances as well as recognizing addiction and misuse is imperative. The use of pain assessment tools and potential substance misuse is essential for delivering high-quality, effective, and patient-centered care. Prescribers should also be mindful of palliative and hospice care principles.

State and Federal Laws on Prescribing Controlled Substances

There are state and federal regulations on prescribing controlled substances. A significant factor is if controlled substances are required to be submitted electronically. Not all states currently mandate that controlled substances be prescribed electronically, though a significant majority do. The federal government has mandated electronic prescribing for controlled substances (EPCS) for Medicare Part D, but states have their specific regulations and deadlines. As of recent updates, states have enacted mandates requiring electronic prescriptions for all controlled substances, with some states providing waivers or exceptions under certain conditions. Implementing these requirements can help combat opioid misuse and improve prescription safety.

New York (NY) Controlled Substance Prescribing Laws

The state of New York has implemented numerous laws designed to improve the safety and efficacy of NY controlled substance prescribing, reduce misuse and diversion, and ensure that prescribers have the necessary education to manage these substances responsibly.

Electronic Prescribing (E-Prescribing)

Mandatory E-Prescribing: New York is among the states that require all prescriptions for NY controlled substances to be issued electronically, except under certain circumstances such as technological failure or specific patient scenarios. Prescribers must be familiar with the particular regulations and guidelines governing these exceptions, and document any use of exceptions appropriately.

The following are key exceptions to mandatory electronic prescribing in New York:

- Temporary Technological or Electrical Failure: If a prescriber is experiencing a temporary technological or electrical failure that prevents the use of electronic prescribing systems, they may issue a paper prescription. This situation should be documented, and the prescription must comply with all other applicable regulations.

- Waiver Granted by the Commissioner of Health: Prescribers who have been granted a waiver by the New York State Commissioner of Health due to economic hardship, technological limitations, or other exceptional circumstances can issue non-electronic prescriptions. Waivers are typically granted for a specific period and may require periodic renewal.

- Practitioner Dispenses Directly: If a practitioner dispenses the medication directly to the patient (e.g., samples or medications given in the office), they are not required to issue an electronic prescription.

- Out-of-State Prescriptions: Prescriptions issued by licensed practitioners practicing in another state and who do not regularly practice in New York are exempt from the electronic prescribing requirement.

- Long-Term Care Facilities: In some cases, medications prescribed to patients residing in long-term care facilities may be exempt from electronic prescribing requirements, depending on specific circumstances and regulatory guidelines.

- Emergency Situations: In cases of emergencies medication should be given immediately, and electronic prescribing is not practical, prescribers may issue a paper prescription. Documentation is necessary and the prescription must meet all other regulatory requirements.

- Public Health Emergencies: During public health emergencies or situations where electronic prescribing systems are compromised or unavailable, exceptions may be made to allow for non-electronic prescriptions.

- Complicated Medications with Lengthy Instructions: The use of this exception must meet exception requirements and must be documented properly.

Mainstreaming Addiction Treatment Act

The Mainstreaming Addiction Treatment (MAT) Act is a federal law and became effective in 2022. Important changes resulting from this act, include (12):

- Elimination of the requirement for registration through the federal Drug Enforcement Administration to prescribe or dispense buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD).

- Elimination of the limitations on the number of patients a practitioner was permitted to treat with buprenorphine for OUD.

Essentially, prescribers holding a standard DEA registration can prescribe buprenorphine for the treatment of OUD, without limitation to the number of patients or a special waiver or registration through the DEA.

Annual Opioid Antagonist Prescription Requirement

Effective June 2022, the Public Health Law Section 3309(7) requires prescribers to prescribe an opioid antagonist along with the first opioid prescription to specific patients every year when any of the following risk factors are present (12):

- A history of substance use disorder (SUD)

- High-dose or cumulative prescriptions that result in 90 morphine milligram equivalents or higher per day

- Concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepine or nonbenzodiazepine sedative hypnotics.

This requirement does not apply in the following settings:

- General Hospitals

- Skilled Nursing Facilities

- Mental Health Facilities

- Patients under Hospice Care

Information on this law can be found here: Section 3309 - Opioid overdose prevention.

New York’s 7-Day Rule for Opioid Prescribing

In New York State, the 7-day rule, effective since 2016, limits the initial opioid prescription for acute pain to a 7-day supply (9). This regulation aims to reduce opioid overprescribing and misuse. Providers can prescribe additional supplies of opioid drugs after the initial 7-day period if needed, but they must follow existing rules and regulations for renewals and refills.

Prescription Monitoring Program (PMP) Requirements

The I-STOP Act is a law that mandates that prescribers review the state's PMP registry before prescribing Schedule II, III, and IV controlled substances. The purpose of this initiative is to monitor and prevent prescription drug misuse and diversion.

There are online instructional webinars available that provide education on topics associated with the New York State Prescription Monitoring Program Registry (PMP), including the PMP registry search and use of the PMP Data Collection Tool (12).

Written Treatment Plan for Opioid Prescribing

Effective April 1, 2018, a written treatment plan in the patient’s medical record is required if a practitioner prescribes opioids for pain that has lasted for more than three months or past the time of normal tissue healing (12).

Specific Controlled Substance Regulations

- Schedule II substances require a written or electronic prescription, and refills are not permitted.

- Schedule III-V substances can be prescribed with up to five refills within six months from the date of issue.

Reporting Requirements

- Prescribers must report any dispensed controlled substances to the NYS Department of Health within 24 hours to ensure accurate and up-to-date tracking of NY controlled substances.

Safe Disposal and Prevention Measures

- Drug Take-Back Programs: Prescribers are encouraged to educate patients about proper disposal of unused medications through approved drug take-back programs to prevent misuse.

- Opioid Stewardship Act: Enforces measures for safe opioid prescribing and patient education on the risks of opioid use and misuse.

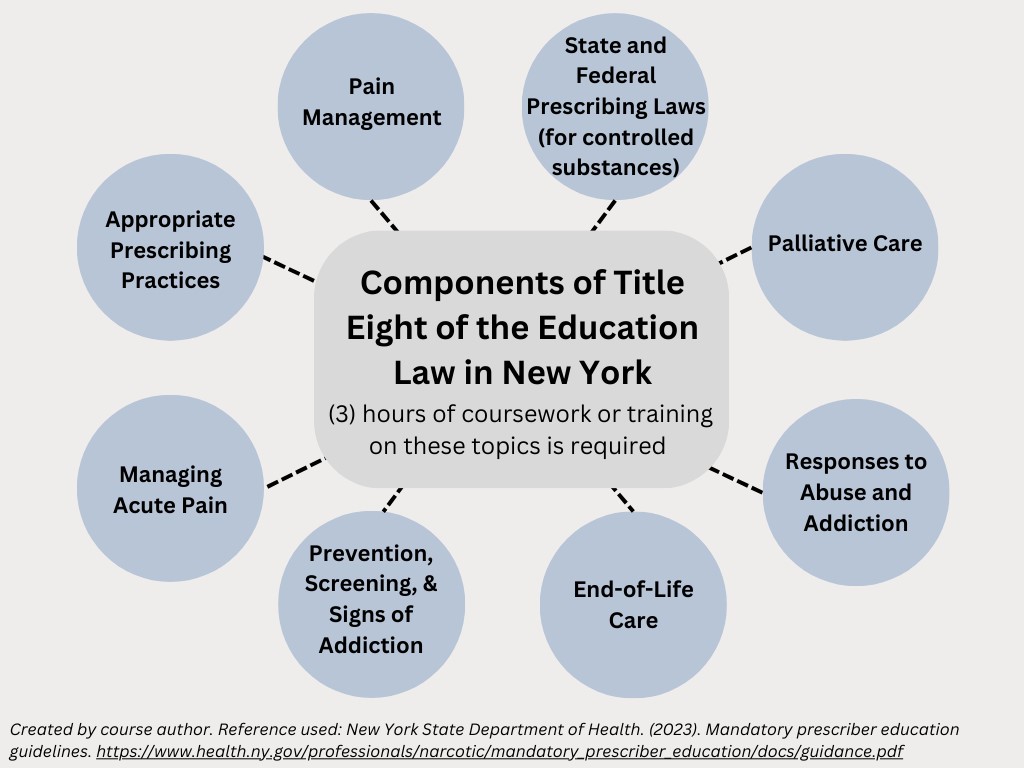

Title Eight of the Education Law in New York

Title Eight of the Education Law in New York mandates that healthcare professionals with the prescribing authority and who possess a DEA registration number to prescribe NY controlled substances must complete specific educational requirements. This training must incorporate pain management, palliative care, and addiction and should be a minimum of three hours. These requirements must be met every three years.

The training covers eight key areas:

- State and federal laws on prescribing controlled substances

- Pain management

- Appropriate prescribing practices

- Managing acute pain

- Palliative care

- Prevention, screening, and signs of addiction

- Responses to abuse and addiction

- End-of-life care

Upon completion of all required eight (8) training topic areas, practitioners must attest to the completion of this education to the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH). Documentation of the completion of the course work or training must be maintained by the prescriber for a minimum of six (6) years from the date of the applicable attestation deadline, for audit purposes.

For more information on the mandatory prescriber education requirement, the attestation form, and Frequently Asked Questions, please visit the Department’s Bureau of Narcotic Enforcement website at: http://www.health.ny.gov/professionals/narcotic/.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you describe the mandatory E-Prescribing laws in New York?

- What is the I-STOP Act?

- Can you name the components of Title 8 of the Education Law in NY, as it relates to required education for prescribers?

- What is the timeframe allowed for the initial prescribing of narcotics for acute pain management?

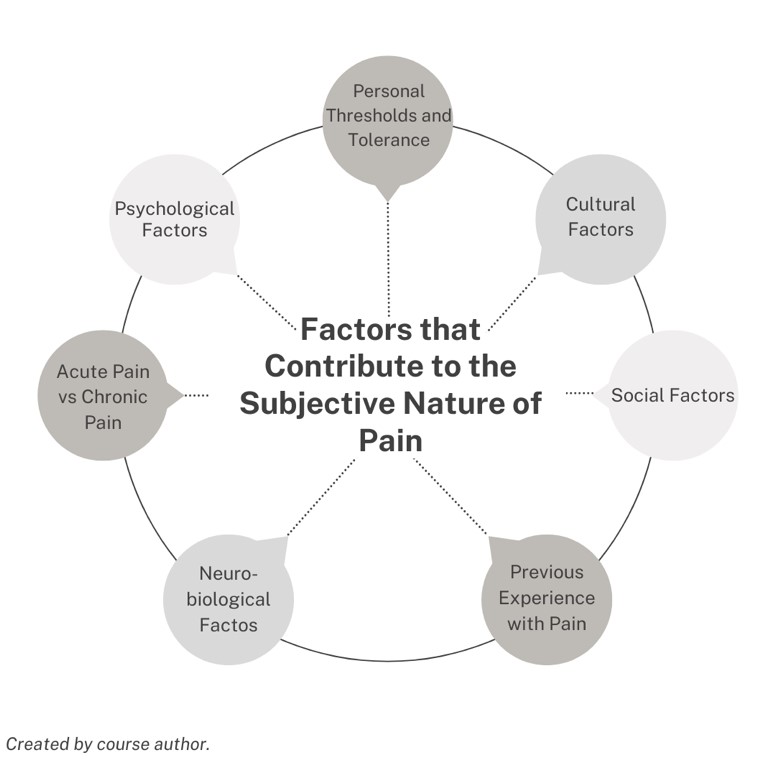

Pain Basics

Pain is defined as a subjective experience, which means it cannot be directly observed by those who are not experiencing it. Pain varies greatly from person to person. Pain basics include factors contributing to pain’s subjectivity, pain types, descriptors, and psychological aspects.

Factors Contributing to Pain’s Subjectivity

- Personal Thresholds and Tolerance: Individuals have different pain thresholds and levels of pain tolerance. These thresholds and tolerances can be influenced by genetics, past experiences, and psychological factors.

- Cultural and Social Influences: Cultural background and social conditioning can affect how people perceive and express pain.

- Psychological Factors: Emotions, stress, and mental health conditions can influence the perception of pain. An example is depression, which can exacerbate symptoms of pain.

- Previous Experiences: Past experiences with pain can shape how future pain is perceived. A person who has endured significant pain in the past might react differently to a similar pain compared to someone who has had minimal painful experiences.

- Neurobiological Factors: The neurological system, including how pain signals are processed in the brain, can vary between individuals. Neurological conditions all impact the experience of pain.

Pain cannot be measured objectively in the same way as other physical parameters like temperature or blood pressure. Instead, healthcare providers rely on self-reports from patients and descriptive scales to assess and manage pain.

A meaningful definition of pain was described by McCaffery and Beebe in 1989 as: “Pain is whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever the experiencing person says it does” (14). The exception to this would be individuals with cognitive impairment or inability to verbally communicate their pain.

Pain has been established as the “fifth vital sign” and evaluation of pain is considered as basic as the assessment and management of temperature, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and heart rate.

Types of Pain

Pain can be classified as acute or chronic. Acute and chronic pain differ in their duration, causes, and implications for treatment. Understanding these differences helps in the appropriate management of pain, ensuring that those with acute and chronic pain receive the care and support they need.

Acute pain occurs abruptly and often has a specific cause or trigger, such as an injury or illness. Acute pain is short-term, typically lasting less than three months, and usually resolves once the underlying cause is treated or healed.

Common causes of acute pain include:

- Trauma or impact

- Surgery

- Broken bones

- Dental work

- Burns or cuts

- Labor and childbirth

Although uncomfortable for the one experiencing the pain, acute pain has a meaningful purpose and often serves as a warning signal to the body, alerting it to injury or illness that needs attention. Acute pain also triggers protective reflexes, such as pulling your hand away from a hot surface or a sharp object.

Acute pain is usually described as sharp in quality and severe, but it may vary depending on the cause. It often comes on suddenly and is accompanied by visible signs of injury or illness, like swelling, redness, or warmth.

Treatment for acute pain focuses on addressing the underlying cause, such as medication for pain relief, physical therapy, or surgery. It often includes analgesics like NSAIDs or opioids.

Chronic pain persists for longer periods, typically defined as lasting more than three months, and can continue even after the initial injury or illness has healed. It is described as a multidimensional syndrome because the pain can have a profound impact on mental health (anxiety, depression), daily activities (physical, professional, social), and overall quality of life.

In the United States, musculoskeletal pain is increasingly prevalent and is a leading cause of disability (6).

Chronic pain can be more complex to manage and may not have a clear, ongoing cause. Sometimes, chronic pain may occur without any obvious injury or illness. The most common source of chronic pain is musculoskeletal conditions such as back pain or joint pain. It can also result from long-term conditions like arthritis, cancer, neuropathy, or fibromyalgia.

Chronic pain is linked to conditions that include:

- Headache

- Orofacial pain

- Cancer

- Neuropathic pain

- Fibromyalgia

Subsequent manifestations of this pain can include:

- Muscle tension and soreness

- Fatigue

- Decreased energy and motivation

- Loss or change in appetite

- Decreased mobility

- Depression

- Anxiety

Managing chronic pain often requires a multidisciplinary approach, including medications, physical therapy, psychological counseling, dietary changes, and lifestyle changes. Treatment aims to reduce pain, improve function, and enhance the quality of life, rather than eliminate the pain.

Other Descriptors of Pain

Pain can also be characterized as nociceptive, neuropathic, inflammatory, and nociplastic.

- Nociceptive pain is a typical result of excessive stimulation of sensory neuroreceptors that occurs with a normally functioning somatosensory system.

- Inflammatory pain is often of internal origin (e.g. infection, osteoarthritis, digestive pain).

- Neuropathic pain is caused by an abnormality in the peripheral or central somatosensory nervous system. 10% of the United States population complain of neuropathic pain.

- Nociplastic (psychogenic or dysfunctional) pain does not have an origin but is mainly caused by psychological factors.

A sharp or throbbing pain is more likely to be acute nociceptive pain. Pain that is described as burning, shooting, pins, and needles, or electric shock-like points toward a neuropathic origin of pain.

Somatization can be described as a tendency to experience and communicate psychological distress in the form of physical (somatic) symptoms and to seek medical help for them.

Somatosensation encompasses sensations such as touch, pressure, temperature, itch, and pain.

Psychological Aspects of Pain

Chronic pain brings psychological distress, and in return, a cycle of psychological factors can worsen chronic pain. Depression and anxiety can make individuals more susceptible to developing chronic pain conditions. Conversely, chronic pain often leads to increased anxiety and depression, forming a vicious cycle.

Within the biopsychosocial model, negative and discouraging beliefs about pain have a detrimental impact on patients’ overall health, self-efficacy, and function. Thoughts can positively influence beliefs about the pain experience if there is control in managing pain, confidence that harm and disability will not occur, and expectations of recovery.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) essentially examines an individual’s thoughts and determines if they are accurate and helpful (14). If thoughts are found to be untrue and destructive, mental health professionals can help individuals consider alternate patterns of thinking and beliefs about pain. For example, “I will never enjoy life again with this pain”, or pain catastrophizing, which is the belief that the pain will never go away and will only worsen.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Do you have experience with patients who have various forms of chronic pain?

- Have you witnessed the psychological impact acute or chronic pain can have on an individual?

- How is therapy altered for acute vs chronic pain?

- What are the differences in duration and pain quality in acute and chronic pain?

Pain Assessment Tools and Techniques

Standardized pain assessment tools are an objective way of monitoring pain levels, quality, aggravating factors, and improvement. The use of pain assessment tools is essential for delivering patient-centered care, ensuring that pain is appropriately recognized and managed.

Using pain assessment tools is crucial to holistic care for several reasons:

- Pain assessment tools provide a standardized way to quantify pain, helping healthcare professionals to assess and compare pain levels more reliably.

- Pain assessment tools enhance communication between patients and healthcare providers as well as ongoing communication between the healthcare team.

- Healthcare providers can appropriately determine the type and dosage of pain relief measures when applying these measurements of pain.

- The regular use of pain assessment tools allows for continuous monitoring of a patient’s pain levels and helps in evaluating the effectiveness of treatments over time.

- Pain assessment tools can aid in identifying changes in a patient's condition.

- Pain assessment tools provide a documented record of a patient’s pain levels and the interventions used. This documentation is meaningful for legal, regulatory, and quality improvement purposes.

- These tools include and empower patients in their treatment plans. This can lead to better adherence to treatment plans and a greater sense of control over their pain management.

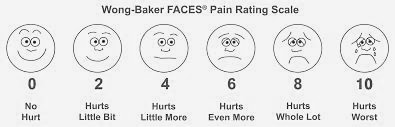

Asking the severity of pain on a scale from 0 to 10, with “0” being no pain and “10” being the worst pain imaginable is a common question used to screen patients for pain. This question is acceptable to initially screen a patient for pain, but a thorough pain assessment is required if any pain above 0 is reported.

In this NY Controlled Substance Prescribing course, we will explore the following tools for assessing pain:

- The “PQRSTU” and “OLDCARTES” mnemonics

- Faces Scale

- FLACC Scale

PQRSTU Assessment

The “PQRSTU” assessment mnemonic:

- Provocation/ Palliation: What makes your pain worse? Better?

- Quality: What does the pain feel like? (Ex: “aching,” “stabbing,” or “burning.”)

- Region: Where exactly do you feel the pain? Does it move around or radiate elsewhere?

- Severity: How would you rate your pain on a scale of 0 to 10, with “0” being no pain and “10” being the worst pain you’ve ever experienced?

- Timing/Treatment: When did the pain start? What were you doing when the pain started? Is the pain constant or does it come and go? How long does the pain last?

- Understanding: What do you think is causing the pain?

OLDCARTES Assessment

The “OLDCARTES” assessment mnemonic:

- Onset: When did the pain start? How long does it last?

- Location: Where is the pain?

- Duration: How long has the pain been going on? How long does an episode last?

- Characteristics: What does the pain feel like? Can the pain be described in terms such as stabbing, sharp, dull, aching, piercing, or crushing?

- Aggravating factors: What brings on the pain? What makes the pain worse? Are there triggers such as movement, body position, activity, eating, or the environment?

- Radiating: Does the pain travel to another area of the body, or does it stay in one place?

- Treatment: What has been done to make the pain better and has it been helpful? Examples include medication, position change, rest, and application of hot or cold.

- Effect: What is the effect of the pain on participating in your daily life activities?

- Severity: Rate your pain from 0 to 10.

FACES Scale

The FACES scale is a visual tool for assessing pain in those who cannot quantify the severity of their pain on a scale of 0 to 10. This may include those with cognitive impairment or children.

Figure 1. Wong-Baker FACES® Pain Rating Scale (21)

FLACC Scale

The FLACC (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability) scale is a measurement used to assess pain for children or individuals who are unable to verbally communicate their pain. The scale is scored in a range of 0–10 with “0” representing no pain.

|

Criteria |

Score 0 |

Score 1 |

Score 2 |

|

Face |

No expression |

Occasional grimace or frown, withdrawn. |

Frequent to constant quivering chin, clenched jaw |

|

Legs |

Normal position or relaxed |

Uneasy, restless, tense |

Kicking, or legs drawn up |

|

Activity |

Lying quietly in a normal position |

Squirming, shifting, back and forth, tense |

Arched, rigid or jerking |

|

Cry |

No cry (awake or asleep) |

Moans or whimpers; occasional complaint |

Crying steadily, frequent screams |

|

Consolability |

Content, relaxed |

Reassured by occasional touching/ distractible |

Difficult to console or comfort |

Table 1. The FLACC Scale (22)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Are you familiar with these pain assessment tools?

- How is pain assessment modified for individuals with cognitive impairment?

- Why are standardized assessment tools important in managing pain?

- Which of these tools would be more appropriate for a non-verbal patient?

Pain Management

Setting appropriate and achievable goals and expectations of treatment is critical. The goals must be unique to each individual and center around the patient’s activities of daily living and function.

Pain management goals can include the absence of pain; however, absence may not always be possible, and goals should focus on the reduction of pain to a level that the patient can have optimal functioning. Practical, measurable goals should specify an action and frequency.

Components of goals:

- Behavior is within the individual’s control and is practical, being they were able to do this before the pain.

- Goal is measurable

- Not primarily focused on pain reduction (i.e., reduce pain totally or by a specific amount)

Examples of appropriate goals:

- Being able to do one load of laundry once a week.

- Being able to walk to the mailbox each day.

- Take dogs to the park for 30 minutes once per week.

Recent evidence-based clinical practice guidelines from the American College of Physicians strongly recommend that clinicians should initially select nonpharmacologic treatment, including multidisciplinary rehabilitation, exercise, acupuncture, yoga, or mindfulness-based stress reduction. The guidelines also encourage the patient's active involvement in their care planning.

| Non- Pharmacological Pain Therapies | Description |

| Therapies and Rehabilitation |

|

| Self-Care |

|

| Complementary Therapies |

|

| Behavioral And Mental Health Therapies |

Psychiatrists, clinical social workers, and mental health counselors provide therapies that identify and treat mental disorders or substance abuse problems that may serve as barriers to pain management. |

Non-Pharmacological Approaches to Pain Management

Individualized care is a collaborative process among patients and their multidisciplinary care team. Pain management should include the patients, caregivers, and various healthcare providers. Individualized care can improve aspects of physical health, mental health, and the ability to self-manage conditions.

Non-Pharmacological Pain Management: Physical and Occupation Therapy

Physical and occupational therapy are highly effective for pain management, function improvement, strength, and overall well-being. Physical therapy focuses on exercises and activities that enhance mobility, strength, and flexibility, which help reduce pain by alleviating stiffness and strain. Additional techniques include massage, heat/cold therapy, and electrical stimulation to provide direct pain relief and promote healing of injured tissues. Physical therapists provide essential education on body mechanics and posture that further helps to prevent pain and injury. These therapies often help patients avoid addictive pain medications, surgeries, and invasive procedures.

Physical therapy generally leads to improved outcomes and decreased health care costs.

Physical therapy interventions can integrate the following:

- Exercise

- Passive Therapy

- Heat or Ice

- Massage

- Ultrasound

- TENS and Electrical Stimulation

- Dry needling

- Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE)

Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE) is a vital part of the management of acute and chronic pain.

Neuroscience pain experts have found that learning about pain through pain neuroscience education (PNE) can improve symptoms, mobility, and feelings of psychological well-being in those with chronic pain. Essentially, teaching patients about their pain and why it is happening can ultimately lead to better outcomes in PT sessions and long-term goals. Physical therapists may spend time teaching about pain, why the pain may be occurring, and how an individual can take control of pain.

Occupational therapy, on the other hand, helps patients modify their daily activities and environments to reduce pain and prevent injury. By teaching pain management strategies, recommending ergonomic adjustments, and improving strength and endurance, occupational therapists enable patients to perform daily tasks with less discomfort. They also address the psychological aspects of pain, providing support and coping mechanisms.

The use of concurrent physical and occupational therapy offers a holistic and comprehensive approach to pain management. They empower patients to take an active role in their care, improving pain levels, function, and quality of life.

The following are methods of overall reduction in pain and improvement of quality of life:

- Encourage positive health habits, roles, and routines gained in OT and PT.

- Set goals that are client-centered, and occupation-based.

- Encourage proactive problem-solving habits.

- Prevent pain onset by self-management techniques.

- Teach ways to avoid fear-avoidance, avoiding tasks due to fear of pain.

- Educate the client on energy conservation.

- Consider whole-body exercises such as yoga, stretching, and tai-chi.

- Focus on problem-solving and how to live with the pain.

Collaboration among the healthcare team is critical. Medical staff can gain vital insight from therapists on goals and outcomes and in turn relay information about opioid analgesics and other symptom-targeted treatments.

Non-Pharmacological Pain Management: Cold Therapy

Clinicians must recognize the underlying pathophysiology that occurs with the application of ice or heating pads/products. It may seem simple, but there are key indicators that could either improve pain or cause worsening or additional injuries.

The application of cold is better for immediate injuries and heat is typically better for chronic conditions. Patients can implement this therapy on their own, and this independent activity may increase self-efficacy and reduce negative thought patterns. However, safety practices should be taught to patients to avoid injuries from the cold or heat.

Common types of cold therapy:

- Cold packs

- Cold compresses

- Aquathermia pad (attached to a cooling/heating unit): The unit has two hoses and is filled with distilled water to bring it to the desired temperature. The water flows through one of the hoses and into the tubes in the pad.

Cold therapy uses:

- Acute musculoskeletal injuries

- Muscle spasming and contraction

- Post-surgical intervention

Guidelines for using cold therapy include:

- Limit duration of application. Prolonged exposure to the cold application can result in hypoxia and tissue damage, rebound inflammation, and frostbite.

- Monitor patient reaction. Assess the skin appearance. A splotchy, white appearance, or if the patient complains of numbness or burning, could indicate impaired blood flow to the tissue receiving cold application.

- Review provider orders. Typically, cold therapy is executed for 15 to 20 minutes at a time depending on the condition or injury. For an acute musculoskeletal injury, the cold application may be repeated every 2 hours as well.

- Document the type of cold therapy, the duration, the patient’s reaction, and the effect.

Non-Pharmacological Pain Management: Heat Therapy

The application of heat causes blood vessels in the area to dilate; this increase in blood flow brings more oxygen and nutrients to the surrounding tissue for healing. The vasodilation also encourages excess fluid to be removed from the area more effectively.

Heat can help to relieve pain, relax muscles, promote healing, reduce tissue swelling, and decrease joint stiffness. The sensation of heat may decrease the transmission of pain signals to the brain, which can relieve pain and discomfort.

Heat applications are used for chronic, or ongoing, conditions. These include back pain and arthritis; heat may also be used only after the first two to three days following an acute, or sudden, injury (1).

Research studies have found the appropriate heat application is effective in relieving chronic lower back pain and chronic knee pain.

Common types of heat therapy:

- Aquathermia pad

- Hot packs (produces dry heat; used to treat muscle sprains and mild inflammations)

Some hot packs are filled with hot fluid and may be heated in the microwave, in hot water, or by striking or squeezing them to activate chemicals. The water temperature of a hot pack should not exceed 110°F or 43°C.

Guidelines for using heat therapy include:

- Apply for 20 to 30 minutes every 2 to 3 hours

- Leaving heat packs in place longer than 45 minutes can cause a rebound phenomenon (constriction of vessels instead of dilation)

Patient education and empowerment can have a significant impact on pain management.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some safety guidelines for using heat therapy?

- Can you describe injuries and pain that ice and cold therapy would be more appropriate than heat therapy?

- Are you familiar with devices that deliver cold and heat therapy?

- How would you describe the role of physical and occupational therapy in the management of acute and chronic pain?

Non-Pharmacological Pain Management: Cognitive and Behavioral Strategies

Researchers have studied several types of non-pharmaceutical pain management methods that have been proven effective in chronic pain management; these include:

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

- Mindfulness-based therapy

Both strategies have been shown to improve psychological adjustment to pain and coping with it.

Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) is a type of psychotherapy that focuses on unhelpful or unhealthy ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving.

The goal of CBT in the management of pain is to provide individuals with an active, problem-solving approach to manage and decrease the challenges associated with chronic pain. By applying these helpful strategies, it is possible to change one’s pain experience, physically and emotionally.

Goals of CBT for pain management (14):

- Contradict false and discouraging concepts of pain control and management

- Increase participation in meaningful activities

- Manage pain flare-ups more effectively

- Reduction in worries and anxiety about increased pain or injury

- Improvement of overall quality of life

Mindfulness is practicing a state of awareness and staying present or mindful in daily life, rather than thinking of the past or future. Mindfulness involves various techniques and practices. Being present is an ongoing practice and consistent dedication to actions and thoughts, rather than a single action.

Two major concepts of mindfulness may help reduce various forms of psychological distress:

- Awareness of oneself and immediate surroundings.

- Non-judgmental acknowledgment and acceptance of what is being experienced from moment to moment.

By using certain mental and physical tools, such as mindful breathing, meditation, and body scans, individuals can direct their attention to the present moment, which can help to cultivate everything from inner stillness to self-control.

Research studies reinforce the positive effects of mindfulness, revealing an association with psychological health improvement and differences in brain activity (13). These studies indicate that the practice of mindfulness alters brain pathways and function in areas of the brain, including the medial cortex, default mode network, insula, amygdala, lateral frontal regions, and basal ganglia; these areas in the brain are involved in the transmission of pain sensations as well.

Non-Pharmacological Pain Management: Acupuncture

Acupuncture is a technique in which fine needles are inserted into the skin to treat certain conditions and interrupt pain transmission. The needles may be manipulated manually by a practitioner, or stimulated with small electrical currents, which is called electroacupuncture. According to national survey data, acupuncture is most commonly used for back, joint, or neck pain.

Acupuncture has been practiced for at least 2,500 years and originated from traditional Chinese medicine. According to the World Health Organization, acupuncture is used in 103 of 129 countries that reported data (9).

There has been a rapid rise in the use of this technique in the United States over the past few decades.

Non-Pharmacological Pain Management: Yoga

A systematic review explained by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (2020) notes yoga as an effective tool in the management of specific types of chronic pain.

Studies have found that yoga can be helpful in the following conditions:

- Fibromyalgia

- Low-back pain

- Neck pain

- Arthritis

Non-Pharmacological Pain Management: Nutritional Consult

Adequate nutrition plays a role in inflammatory and metabolic concepts that impact pain management. There is a substantial relationship between nutrition and chronic pain, but not typically integrated into the care plan despite the emerging evidence that poor nutrition and dietary intake play a key role in the development and management of chronic pain (7). Health professionals need to be aware of and understand the role nutrition plays in chronic pain

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some goals of cognitive behavior therapy in pain management?

- What are the American College of Physicians’ recommendations in the initial treatment of acute pain?

- How would you describe the role of nutrition and reduced inflammation in the experience of pain? For which conditions is yoga helpful?

Pharmacological Approaches to Pain Management

|

Non-Opioid Drug Class |

Description |

|

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs |

|

|

Controlled Substances |

Description |

|

Schedule II & IIN

|

Opioids and Opiates

|

|

Schedule III |

|

|

Schedule IV |

|

|

Adjuvant Medications |

Description |

|

Anticonvulsants |

|

|

Antidepressants |

|

|

Topicals: Medicated Creams, Foams, Gels, Lotions, Ointments, Patches |

|

|

Interventional Pain Management |

|

Pharmacological Pain Management: NSAIDs

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are a drug class FDA-approved for use as antipyretic, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic agents. NSAIDs are used for treating muscle pain and strains, dislocations, dysmenorrhea, arthritic conditions, pyrexia, gout, and migraines.

NSAIDs are typically divided into groups based on their chemical structure and selectivity:

- Acetylated Salicylates (Aspirin)

- Non-acetylated Salicylates (Diflunisal, Salsalate)

- Selective COX-2 Inhibitors (Celecoxib, Etoricoxib).

- Propionic Acids (Naproxen, Ibuprofen

- Acetic Acids (Diclofenac, Indomethacin)

- Enolic Acids (Meloxicam, Piroxicam)

- Anthranilic Acids (Meclofenamate, Mefenamic Acid),

- Naphthylalanine (Nabumetone)

Topical NSAIDs are also available for use.

Mechanism of Action of NSAIDs: The primary mechanism of action of NSAIDs is the inhibition of the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX); this enzyme converts arachidonic acid into thromboxanes, prostaglandins, and prostacyclins (5). Prostaglandins cause vasodilation, help regulate temperature, and play a vital role in anti-nociception of pain; thromboxanes aid in platelet adhesion (5)

There are two cyclooxygenase isoenzymes: COX-1 and COX-2.

- COX-1 impacts gastrointestinal mucosa lining, kidney function, and platelet aggregation.

- COX-2 is expressed during an inflammatory response.

The majority of NSAIDs inhibit both COX-1 and COX-2; except COX-2 selective NSAIDs (ex. celecoxib) only target COX-2. The COX-2 essentially provides anti-inflammatory relief without compromising the gastric mucosa.

NSAIDs are contraindicated in the following patients:

- Those with NSAID hypersensitivity or salicylate hypersensitivity

- Those who have experienced an allergic reaction after taking NSAIDs

- Those who have undergone coronary artery bypass graft surgery

- Patients in the third trimester of pregnancy

Adverse/ Side Effects: NSAIDs have well-established adverse effects affecting the gastric mucosa, renal system, cardiovascular system, hepatic system, and hematologic system (5)

The most frequently reported side effects of NSAIDs are gastrointestinal symptoms, such as:

- Heartburn

- Stomach pain

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Constipation

Taking NSAIDs with food, milk or antacids may reduce these symptoms.

Additional side effects of NSAIDs include:

- Dizziness.

- Difficulty concentrating

- Mild headaches

Pharmacological Pain Management: Opiates and Opioids

Opiates are chemical compounds that are extracted or refined from natural plant matter (poppy sap and fibers).

Examples of opiates:

- Opium

- Morphine

- Codeine

- Heroin

Opioids are chemical compounds that are generally not derived from natural plant matter. Most opioids are synthesized. Some opioids are partially synthesized from chemical components of opium, while other commonly used opioid molecules are designed and manufactured in laboratories. The pharmaceutical industry has created more than 500 different opioid molecules.

Common opioids used in the United States for pain management:

- Fentanyl/fentanyl

- Dextropropoxyphene

- Hydrocodone

- Oxycodone

- Oxymorphone

- Meperidine

Pharmacological Pain Management: Fentanyl

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid agonist that is 80-100 times stronger than morphine and is often added to heroin to increase its potency (4). Fentanyl is significantly more potent than other opioids. Fentanyl can cause severe respiratory depression and has high addiction potential.

Fentanyl drug information (15):

Drug Class

- Opioid, narcotic agonist (Schedule II).

Uses

- Pain relief, preop medication; adjunct to general or regional anesthesia. Management of chronic pain (transdermal).

Mechanism of Action

Opioids can be classified according to their effect on opioid receptors and can be considered as agonists, partial agonists, antagonists, and agonist-antagonists.

- Agonists interact with an opioid receptor to produce a maximal response from that receptor.

- Antagonists bind to receptors but produce no functional response, while at the same time preventing an agonist from binding to that receptor (naloxone).

- Partial agonists bind to receptors but elicit only a partial functional response regardless of the amount of drug administered.

- Agonist-antagonists act as agonists to a certain opioid receptor but have antagonist activity to another opioid receptor.

Fentanyl binds to and activates the mu-opioid receptors (MORs) in the brain and spinal cord. These receptors are part of the endogenous opioid system, which regulates pain, reward, and addictive behaviors. Mu-opioid receptors are widely distributed throughout the body and play a crucial role in mediating the effects of opioids. MORs are found in the central nervous system (brain, thalamus, cortex, brainstem, hypothalamus), the spinal cord, peripheral nervous system (nerve endings), gastrointestinal tract, muscle tissue, etc. This wide distribution of MORs in both the central and peripheral nervous systems, as well as in other tissues, explains the broad range of effects opioids have on the body, including analgesia, euphoria, respiratory depression, and gastrointestinal disturbances.

By binding to the mu-opioid receptors, fentanyl inhibits the release of neurotransmitters involved in pain signaling, such as substance P, glutamate, and GABA (15). This interferes with the transmission of pain signals from the peripheral nervous system to the CNS, which essentially reduces the acknowledgment of pain (15).

Fentanyl also increases potassium conduction and decreases calcium influx in neurons, which hyperpolarizes the neuronal membrane and reduces the pain signal transmission. Fentanyl alters the perception of pain by modulating pain pathways at various levels of the CNS, which changes how pain is experienced and processed by the brain.

Fentanyl also produces euphoria and sedation by acting on the reward pathways in the brain, specifically through the mesolimbic dopamine system. This action contributes to its potential for misuse and addiction.

Onset of Action for Adults

- IM: 7 to 8 minutes

- IV: Almost immediate (maximal analgesic and respiratory depressant effects may not be seen for several minutes)

- Transdermal patch (initial placement): 6 hours

- Transmucosal: 5 to 15 minutes

Duration

- IM: 1 to 2 hours

- IV: 0.5 to 1 hour

Protein Binding

- 79% to 87%, primarily to alpha-1 acid glycoprotein; also binds to albumin and erythrocytes.

Metabolism

- Hepatic, primarily via CYP3A4 by N-dealkylation and hydroxylation to other inactive metabolites.

Half-Life Elimination

- IV: Adults: 2 to 4 hours; when administered as a continuous infusion, the half-life prolongs with infusion duration due to the large volume of distribution (Sessler 2008)

- SubQ bolus injection: 10 hours

- Transdermal device: Terminal: ~16 hours

- Transdermal patch: 20 to 27 hours

- Transmucosal products: 3 to 14 hours (dose dependent)

- Intranasal: 15 to 25 hours (based on a multiple-dose pharmacokinetic study when doses are administered in the same nostril and separated by a 1-, 2-, or 4-hour time lapse)

- Buccal film: ~14 hours

- Buccal tablet: 100-200 mcg: 3 to 4 hours; 400 to 800 mcg: 11 to 12 hours

Time to Peak

- Buccal film: 0.75 to 4 hours (median: 1 hour)

- Buccal tablet: 20 to 240 minutes (median: 47 minutes)

- Lozenge: 20 to 480 minutes (median: 20 to 40 minutes)

- Intranasal: Median: 15 to 21 minutes

- SubQ bolus injection: 10 to 30 minutes (median: 15 minutes) (Capper 2010)

- Sublingual spray: 10 to 120 minutes (median: 90 minutes)

- Sublingual tablet: 15 to 240 minutes (median: 30 to 60 minutes)

- Transdermal patch: 20 to 72 hours; steady-state serum concentrations are reached after two sequential 72-hour applications

Excretion

- Urine 75%; feces ~9%

Side Effects

- IV: Postop drowsiness, nausea, vomiting.

- Transdermal: Headache, pruritus, nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, dyspnea, confusion, dizziness, drowsiness, diarrhea, constipation, decreased appetite.

Adverse Effects

Overdose or too-rapid IV administration may produce severe respiratory depression, skeletal and thoracic muscle rigidity. This muscle rigidity may lead to apnea, laryngospasm, bronchospasm, cold/clammy skin, cyanosis, and coma. Tolerance to analgesic effect may occur with repeated use. The antidote for Fentanyl is naloxone.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What is the time of onset for the various forms of fentanyl?

- How is the half-life meaningful when prescribing fentanyl?

- What are some common side effects of fentanyl?

- Can you name some management strategies for these side effects?

Nursing Considerations for Fentanyl Administration

Considerations for the nurse administering Fentanyl include (15):

- Prepare: Resuscitative equipment and opiate antagonist (naloxone 0.5 mcg/kg) should be available for initial use.

- Establish baseline blood pressure, pulse rate, and respirations.

- Assess the type, location, intensity, and duration of pain using a standardized assessment tool.

- Assess fall risk and implement appropriate precautions.

- Monitor respiratory rate, B/P, heart rate, oxygen saturation.

- Re-assess for relief of pain.

- Assist with ambulation and encourage the patient to turn, cough, and deep breathe every two hours.

- For patients with prolonged high-dose use, and continuous infusions (critical care, ventilated patients), clinicians should consider weaning drip gradually or transitioning to a fentanyl patch to decrease symptoms of opiate withdrawal.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How do the mechanisms of action differ between agonists, partial agonists, antagonists, and agonist-antagonists?

- Can you describe how fentanyl prevents the release of pain neurotransmitters?

- Where are MORs located in the body?

- How much more potent is fentanyl than morphine?

Regulation and Schedules of Controlled Substances

The Controlled Substances Act (CSA) requires that all substances must be regulated under existing federal law and categorized into five schedules. The schedule determination is based on the substance’s medical use, potential for abuse, and safety or dependence liability (7).

These factors are listed in Section 201 (c), [21 U.S.C. § 811 (c)] of the CSA as follows (7):

- The actual or relative potential for abuse.

- Scientific evidence of its pharmacological effect, if known.

- The current state of scientific knowledge on the substance or drug.

- The historical pattern of abuse.

- The scope, duration, and significance of abuse.

- Risk to the public health.

- Any psychic or physiological dependence liability.

- If the substance is an immediate precursor of a substance already controlled under this subchapter.

Based upon this law, the United States Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) maintains a list of controlled medications and illicit substances categorized from Schedule I to V. Schedule I drugs are considered to have the highest risk of abuse and have no recognized medical use in the United States. Schedule V drugs have the lowest potential for abuse among controlled substances.

Description of Schedule I through V drugs (7):

Schedule I

- Examples: Marijuana, heroin, mescaline (peyote), lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)

Schedule II

- High abuse potential with severe psychological or physical dependence; however, these drugs have an accepted medical use and may be prescribed, dispensed, or administered.

- Examples: Fentanyl, oxycodone, morphine, hydromorphone

- Schedule II drugs should not have a refill at the pharmacy

Schedule III

- Abuse potential, but considered less than Schedule II

- Examples: Ketamine

Schedule IV

- "Abuse potential less than Schedule II but more than Schedule V medications"

- Examples include diazepam, alprazolam, and tramadol

Schedule V

- The least potential for abuse among the controlled substances.

- Examples: Pregabalin and dextromethorphan

Controlled Substance Addiction

The United States is facing an opioid epidemic with unparalleled impact. Drug overdoses are the leading cause of accidental deaths in the United States (8). Roughly two-thirds of drug overdose deaths were caused by opioids— both legal and illicit (3). There are two intertwined epidemics: the excessive use of opioids for both legal and illicit purposes, and unprecedented levels of consequent opioid use disorder (OUD).

Overview of Addiction Disorders in New York State

New York State has been significantly impacted by addiction disorders, particularly opioid abuse. According to the New York State Department of Health and the Office of Addiction Services and Supports (OASAS), substance use, and related disorders are on the rise. In 2022 approximately 3,030 New Yorkers died of a drug overdose, which is a 12% increase from 2021 (2,696 deaths), and the highest amount since reporting started in 2000. Opioids, particularly fentanyl, were involved in over 84% of these overdose deaths (13).

Commonly Abused Substances

- Opioids

- Stimulants (cocaine and methamphetamine)

- Alcohol

- Cannabis

Substance abuse and overdose are higher among certain demographics of individuals in New York. Overdose fatalities of male New Yorkers were nearly four times as high as the rate among females (13). Blacks have the highest rate, followed by Hispanics/Latino and whites (13). High-poverty neighborhoods had a larger increase in overdose rates in 2022, and these residents in high-poverty neighborhoods had the highest rate of overdose deaths (13).

Opioid Use Disorder

An opioid use disorder (OUD) is defined as a pattern of opioid use that leads to serious impairment or distress (5).

In the late 1990s, prescription opioid use increased in all regions of the United States. Unregulated prescription opioid use was promoted, in large part by the pharmaceutical industry (5). Misuse and diversion of these medications became widespread; by 2017, an estimated 1.7 million people in the United States suffered from substance use disorders related to prescription opioid pain medications (5).

The DSM-5 Criteria is an excellent guide for diagnosing OUD.

To be eligible for methadone treatment, patients must meet DSM-5 criteria for OUD.

DSM-5 Criteria for Opioid Use Disorder:

- Opioids are often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended

- There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control opioid use.

- A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the opioid, use the opioid, or recover from its effects.

- Craving or a strong desire to use opioids.

- Recurrent opioid use causes failure to fulfill major role responsibilities at work, school, or home.

- Continued opioid use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of opioids.

- Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of opioid use.

- Recurrent opioid use in situations in which it is physically hazardous.

- Continued use despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by opioids.

- Tolerance as defined by either of the following: (1) Need for markedly increased amounts of opioids to achieve intoxication or desired effect or (2) Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of opioid

- Withdrawal as manifested by either of the following: (1) Characteristic opioid withdrawal syndrome or (2) The same (or a closely related) substance is taken to relieve or avoid withdrawal

The presence of at least 2 of these symptoms indicates an OUD.

The severity of the OUD is defined as:

- MILD: The presence of 2 to 3 symptoms

- MODERATE: The presence of 4 to 5 symptoms

- SEVERE: The presence of 6 or more symptoms

Diagnosing patients can be a controversial practice. However, establishing this diagnosis is required in some work settings and for third-party billing (2). The DSM-5 no longer includes the terms substance abuse, substance dependence, or addiction because of the lack of clarity and stigma.

Two types of substance-related disorders are distinguished in the DSM-5:

- SUDs

- Substance-induced disorders

- Intoxication, withdrawal, and other substance-induced mental disorders.

- All SUDs in the DSM-5 are diagnosed according to severity based on the number of symptoms.

Drug testing is required in some settings because people with active addictions typically minimize, deny, and lie about the extent of their drug use (2).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How is Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) defined?

- What is the DSM-5 criteria for this diagnosis?

- How can clinicians determine if opioids are having an impact on a patient’s functional level?

- Can you think of reasons it is important to appropriately diagnose the disorder before prescribing medications for the treatment?

Screening and Assessment Tools for Substance Misuse

There are many tools and instruments that can help with OUD assessment. A general history questionnaire is useful for clinicians and counselors, followed by a more specific assessment of substance misuse and addiction.

- The American Psychiatric Association has developed the DSM-5 Self-Rated Level 1 Cross-Cutting Symptom Measures (adult, ages 11– 17, or ages 6– 17) to get a general diagnostic idea of an individual or the specific measure for substance use in each age category. The measures are available from https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm/educational-resources/assessment-measures

Additional Tools:

- The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) - provides several evidence-based screening tools and resource materials.

Signs and Symptoms of Substance Misuse and Addiction

Signs of alcohol and drug use include:

General Appearance

- Disheveled appearance

- Hyperactivity

- Hypoactivity

- Wearing long sleeves at inappropriate times

- Weight gain or loss

Neurological

- Constricted pupil

- Dilated pupils

- Diminished alertness

- Sedated

- Sleepiness

- Insomnia

- Poor concentration

- Poor judgement

- Slurred speech

- Tremors

- Unsteady gait

Mood

- Lying

- Mood changes

- Defensiveness/ paranoia

- Denial

Other

- Bloodshot eyes

- Watery eyes

- Frequent accidents

- Frequent pain complaints

- Perforation of the nasal septum

- Runny nose

- Unexplained nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea

- Diaphoresis

Substance Abuse Among Healthcare Professionals

Unfortunately, there is a high prevalence of substance and alcohol use disorders in healthcare settings, which has increased awareness of the issue. When these disorders occur in healthcare settings, the risk of unintended harm to patients makes this an issue of high importance.

Symptoms of alcohol and substance use disorder within the healthcare setting (19):

- Abnormal wasted opioids

- Altered orders

- Arriving to work late

- Difficulty meeting deadlines

- A discrepancy in controlled substance records

- Dishonesty

- Documentation errors

- Excessive sick time

- Frequent mistakes

- Frequent reports of patients not receiving pain relief

- Frequent unexplained absences

- Maximum use of pain medications

- Not performing narcotic counts

- Obsession with opioids

- Offering to medicate patients

- Poor quality work and poor charting

- Rounding at odd hours

Behaviors that are associated with drug diversion (19):

- Altered orders for drugs

- Discrepancies for controlled substances

- Frequent corrections on medication records

- Higher-than-average opioid administration

- Higher-than-average opioid wastage

- Incorrect opioid counts

- Patients complaining of poor pain relief

- Tampering with capsules or vials

- Unexplained disappearances or trips to isolated areas

Responses to Addiction and Controlled Substance Misuse

New York State has a robust system for addressing addiction, overseen by OASAS. This includes a variety of treatment options, such as outpatient programs, inpatient rehabilitation, medication-assisted treatment (MAT), and harm reduction services. NY integrates a data-driven approach to monitor and respond to addiction trends effectively.

Key Initiatives and Programs

- Prevention and Early Intervention: Programs aimed at reducing the onset of substance use, particularly among youth and high-risk populations.

- Treatment Accessibility: Efforts to make treatment services more accessible, including expanding telehealth options and ensuring coverage for addiction services under health insurance plans.

- Harm Reduction: Distribution of naloxone to reverse opioid overdoses, safe consumption spaces, and needle exchange programs to reduce the harms associated with drug use.

- Recovery Support: Providing long-term support for individuals in recovery, including housing assistance, employment services, and peer support networks.

Responses to Addiction and Controlled Substance Abuse

- Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT)

- Utilizes medications like methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone in combination with counseling and behavioral therapies to treat opioid use disorder (OUD).

- MAT has been shown to reduce opioid use, improve retention in treatment, and decrease the risk of overdose Naloxone Distribution

- Counseling and Behavioral Therapies

- Public Education and Prevention Programs

- Policy and Regulatory Measures

- Support Groups and Peer Support

Outside of prison, the most effective treatment for OUD is a combination of Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) and mental health counseling and therapies.

Medication-Assisted treatment for Opioid Use Disorder

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is the use of medications, in combination with counseling and behavioral therapies, in the treatment of opioid use disorders (OUD). The goal is sustained recovery. Often, individuals have actual, pain, and become dependent on prescription narcotic drugs, then switch to illicit opioids or opiate heroin when the medically supplied narcotics run out.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires that prescribing information for medicines intended for use in the outpatient setting include how to safely decrease the dose. Prescribers should not abruptly discontinue opioids in a physically dependent patient, but slowly taper the dose of the opioid and continue to manage pain therapeutically.

The FDA has only approved three MATs for OUD: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone.

Buprenorphine and methadone have been shown to decrease mortality among those with OUD (16). A recent study reported that buprenorphine was associated with a lower risk of overdose during active treatment compared to post-discontinuation.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you name the drugs approved by the FDA for the treatment of OUD?

- How can partnerships between policymakers and healthcare providers enhance MATs?

- How would you describe your experience with addiction treatment programs?

- Have you ever administered methadone in your nursing practice?

Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: Methadone

Methadone is a medication approved by the FDA to treat OUD and manage chronic pain. Methadone is safe and effective when taken as prescribed. Methadone is a component of a comprehensive treatment plan, which includes counseling and other behavioral health therapies to provide patient-centered care.

Methadone, a long-acting opioid agonist that helps to relieve cravings and withdrawal, while also blocking the effects of opioids (18). Methadone is available in liquid, powder, and diskette forms. Patients taking methadone to treat OUD must receive the medication under the supervision of a medical provider, but after a period of stability and consistent compliance, patients may be allowed to take methadone independently at home between provider visits (18).

Drug information for Methadone includes (12):

Methadone Drug Cass

Opioid agonist (Schedule II)

Methadone Uses

Methadone is a first-line Opioid Addiction Treatment (OAT) option, along with buprenorphine. Methadone may be preferable to buprenorphine for patients who are at high risk of treatment cessation and subsequent fentanyl overdose. It also alters processes affecting analgesia, and emotional responses to pain, and reduces withdrawal symptoms from other opioid drugs (18).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you name the uses of methadone?

- How does the mechanism of action of methadone help to alleviate withdrawal symptoms from opioids?

- Is the half-life of this drug considered long or short?

- Why is it important to recognize that methadone binds to plasma proteins in circulation?

Methadone Pharmacokinetics

Description of methadone pharmacokinetics per route (12):

|

Route |

Onset |

Peak |

Duration |

|

PO |

0.5 – 1 hour |

1.5 – 2 hours |

6 – 8 hours |

|

IM |

10 – 20 mins |

1 – 2 hours |

4 – 5 hours |

|

IV |

n/a |

15 – 20 mins |

|

Methadone is also (18):

- Well-absorbed after IM injection.

- Protein binding: 85%–90%.

- Metabolized in liver. Primarily excreted in urine.

- Not removed by hemodialysis.

- Half-life: 7– 59 hrs.

- Crosses the placenta and is found in breast milk.

Methadone Precautions

Considerations when prescribing methadone (20):

- Respiratory issues may occur in neonates if the mother received opiates during labor.

- Elderly patients are more susceptible to respiratory depressant effects.

- Age-related renal impairment may increase the risk of urinary retention.

- Caution: Renal/ hepatic impairment, elderly/debilitated pts, risk for QT prolongation, medications that prolong QT interval, conduction abnormalities, severe volume depletion, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, cardiovascular disease, depression, suicidal tendencies, history of drug misuse, respiratory disease, and biliary tract dysfunction

Side Effects

As with other opioid medications, general side effects of methadone are related to excessive opioid receptor activity, including but not limited to:

- Diaphoresis/flushing

- Pruritis

- Nausea

- Dry mouth

- Constipation

- Sedation

- Lethargy

- Respiratory depression

Warnings

- May prolong the QT interval, which may cause serious arrhythmias.

- May cause serious, life-threatening, or fatal respiratory depression.

- Monitor for signs of misuse, misuse, and addiction.

- Prolonged maternal use may cause neonatal withdrawal syndrome.

- Do not confuse methadone with Mephyton, Metadate CD, Metadate ER, methylphenidate, or morphine

- Serious adverse effects: pancreatitis, hypothyroidism, Addison’s disease, head injury, increased intracranial pressure.

Methadone Dosing and Titration for Prescribers

Information for prescribers in dosing and titrating methadone include (20):

- The clinician should attempt to reach an optimal dose of methadone safely and quickly (3).

- Starting methadone at 30mg is recommended.

- The starting dose of methadone can be increased by 10–15mg every three to five days.

- Slower titration is recommended for patients at higher risk of toxicity (e.g., older age, sedating medications or alcohol, patients new to methadone).

- Patients who have recently been on methadone dosing at higher doses (i.e., in the previous week) can be considered for more rapid dose increases based on their tolerance.

- Once a dose of 75–80mg is reached, the dose can then be increased by 10mg every five to seven days.

- If four consecutive missed doses, the dose of methadone should be reduced by 50% or to 30mg, whichever is higher. If five or more consecutive doses are missed, methadone should be restarted at a maximum of 30mg and titrated according to patient need.

- SROM at a maximum starting dose of 200mg can be added on the day of a restart, as long as the patient has not become completely opioid-abstinent.

- For patients who use fentanyl regularly, methadone doses of 100mg or higher are often appropriate.

- Use prescription practices that promote treatment retention, including phone visits, check-ins, extending prescriptions, or leaving longer-duration methadone prescriptions for 30mg at the pharmacy so patients can restart treatment.

- Be aware of the limitations of urine drug testing.

- Provide treatment for concurrent psychiatric illnesses and substance use disorders.

Methadone and Pregnancy

Opioid withdrawal is associated with a high risk of spontaneous abortion and preterm labor. Pregnant patients with OUD should be started as soon as possible and titrated to avoid withdrawal symptoms (20). The use of opiates during pregnancy produces withdrawal symptoms in neonates, including irritability, excessive crying, tremors, hyperactive reflexes, fever, vomiting, diarrhea, yawning, sneezing, and seizures (20).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you name drugs that should be carefully monitored when prescribed along with methadone?

- What are examples of additional precautions for elderly patients?

- Can you explain the major side effects of methadone?

- Can you describe the recommendations for missed doses of methadone?

- What symptoms might neonates, who were exposed to opiates while in-utero, experience?

- What are some ways to manage the adverse effects of methadone?

Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine should be used as part of a comprehensive treatment program that includes counseling and psychosocial support.

Buprenorphine is categorized as a Schedule III drug. It is a synthetic opioid developed in the late 1960s and is used to treat OUD. This drug is a synthetic analog of thebaine, which is an alkaloid compound derived from the poppy flower (6).

Buprenorphine is approved by the FDA to treat acute and chronic pain and OUD.

Drug information for buprenorphine include:

Drug Class

- Analgesic, Opioid

- Analgesic, Opioid Partial Agonist

Uses

Buprenorphine is used to treat OUD and pain management in patients for which alternative treatment options (e.g., nonopioid analgesics) are ineffective, not tolerated, or are inadequate to provide sufficient management of pain (16).

Buprenorphine should be used as part of a complete treatment program to include counseling and psychosocial support.

Mechanism of Action

Buprenorphine has an analgesic effect by binding to mu opiate receptors in the CNS; however, it behaves like an antagonist due to it being a partial mu agonist but the analgesic effects plateau at higher doses (16). This is a meaningful attribute, and this plateauing of its analgesic effects at higher doses, causes it to have limited effects on respiratory depression as well (16). This is a positive attribute when considering safety.

Essentially, the benefits of this drug include: (1) higher doses do not lead to greater analgesic effects, thus respiratory depression; and (2) the withdrawal symptoms from buprenorphine are not as intense as full-opioid antagonists.

The extended-release formulation is injected subcutaneously as a liquid (16).

Note on absorption: When administered orally, buprenorphine has poor bioavailability. The preferred route of administration is sublingual, so it can have rapid absorption and circumvents the first-pass effect. Placing the tablet under the tongue results in a slow onset of action, with the peak effect occurring approximately 3 to 4 hours after administration (16).

Pharmacodynamics/Kinetics

Pharmacodynamics/kinetics of buprenorphine includes (16):

- Onset of action: Immediate-release IM: ≥15 minutes

- Peak effect: Immediate-release IM: ~1 hour

- Duration: Immediate-release IM: ≥6 hours; Extended-release SubQ: 28 days

- Absorption: Immediate-release IM and SubQ: 30% to 40%.

- Application of a heating pad may increase blood concentrations of buprenorphine 26% to 55%.

- Distribution: CSF concentrations are 15% to 25% of plasma concentrations

- Protein binding: High (~96%, primarily to alpha- and beta globulin)

- Bioavailability (relative to IV administration): Buccal film: 46% to 65%; Immediate-release IM: 70%; Sublingual tablet: 29%; Transdermal patch: ~15%

- Half-life elimination in adults:

- IV: 2.2 to 3 hours

- Buccal film: 27.6 ± 11.2 hours

- Sublingual tablet: ~37 hours

- Transdermal patch: ~26 hours

- Time to peak, plasma:

- Buccal film: 2.5 to 3 hours

- Extended-release SubQ: 24 hours, with steady state achieved after 4 to 6 months

- Subdermal implant: 12 hours after insertion, with steady state achieved by week 4

- Sublingual: 30 minutes to 1 hour

- Transdermal patch: Steady state achieved by day 3

- Excretion: Most of the drug and its metabolite are eliminated through feces, with less than 20% excreted by the kidneys (6)

- Clearance: Related to hepatic blood flow

- Adults: 0.78 to 1.32 L/hour/kg

Adverse Effects

Buprenorphine has anticholinergic-like effects and may cause CNS depression, dry mouth, dizziness, hypotension, drowsiness, QT prolongation, and lower seizure threshold (6).

Additional adverse effects of buprenorphine include:

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Headache

- Memory loss

- Orthostatic hypotension

- Urinary retention

Following buprenorphine treatment, a patient's tolerance to opioids decreases, increasing the risk for harm if they resume their previous opioid dosage. Patients should be strongly advised against using opioids without prior consultation with their healthcare provider.

Warnings

Prescribers should exercise caution when prescribing buprenorphine to patients with hepatic impairment, morbid obesity, thyroid dysfunction, a history of ileus or bowel obstruction, prostatic hyperplasia or urinary stricture, CNS depression or coma, delirium tremens, depression, anxiety disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and toxic psychosis (16).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you describe the mechanisms of action for buprenorphine?

- What are some comorbidities to be careful with when prescribing this drug?

- How does buprenorphine’s mechanism of action differ from that of opioids?

- Can you describe the analgesic effects of higher doses of buprenorphine?

Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: Naltrexone

Naltrexone is effective in blocking the effects of opioid drugs. Naltrexone is a pure opioid antagonist, it acts as a competitive antagonist at opioid receptor sites, showing the highest affinity for mu receptors (17). Naltrexone was initially developed in 1963 for the treatment of alcohol use disorders; in 1984, naltrexone received approval for medical use in the United States.

Drug information for naltrexone includes:

Drug Class

- Antidote

- Opioid Antagonist

Uses

- Alcohol use disorder: FDA Approved.

- OUD: For the blockade of the effects of exogenously administered opioids; FDA-approved.

- Researchers are studying its use in patients with stimulant use disorder, particularly patients with polydrug dependence on opioids, heroin, and amphetamine (17)

Mechanism of Action

Naltrexone blocks the effect of opioids and prevents opioid intoxication and dependence in opioid users. Naltrexone also helps with alcohol dependency because it modifies the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis to suppress ethanol consumption (17). Opioids act mainly via the mu receptor, although they affect mu, delta, and kappa-opioid receptors. Naltrexone competes for the opiate receptors and displaces opioid drugs from these receptors, thus reversing their effects (17).

Exogenous opioids include the commonly prescribed pain relievers such as hydrocodone, oxycodone, and heroin. These typically induce euphoria at much higher doses than those prescribed by medical providers to relieve pain. If naltrexone occupies the receptors, the opioids are not going to provide these euphoric effects.

According to guidelines by the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM), a combination of buprenorphine and low doses of oral naltrexone is effective for OUD for managing withdrawal (17).

Pharmacodynamics

Duration: Oral: 50 mg: 24 hours; 100 mg: 48 hours; 150 mg: 72 hours; IM: 4 weeks

- Absorption: Oral: Almost complete

- Distribution: Vd: ~1350 L; widely throughout the body but considerable interindividual variation exists

- Metabolism: Extensively metabolized via noncytochrome-mediated dehydrogenase conversion to 6-beta-naltrexol (primary metabolite) and related minor metabolites; glucuronide conjugates are also formed from naltrexone and its metabolites

- Oral: Extensive first-pass effect

- Protein binding: 21%

- Bioavailability: Oral: Variable range (5% to 40%)

- Half-life elimination:

- Oral: 4 hours; 6-beta-naltrexol: 13 hours

- IM: naltrexone and 6-beta-naltrexol: 5 to 10 days (dependent upon erosion of polymer)

- Time to peak, serum:

- Oral: ~60 minutes

- IM: Biphasic: ~2 hours (first peak), ~2 to 3 days (second peak)

- Excretion: Primarily urine (as metabolites and small amounts of unchanged drug)

Side Effects

Commonly reported side effects of naltrexone include:

- Gastrointestinal Distress

- Constipation

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Abdominal pain

- Insomnia

- Joint and muscle pain

- Fatigue

- Decreased strength and energy

- Tooth or gum pain

- Dry mouth

- Increased thirst

Warnings

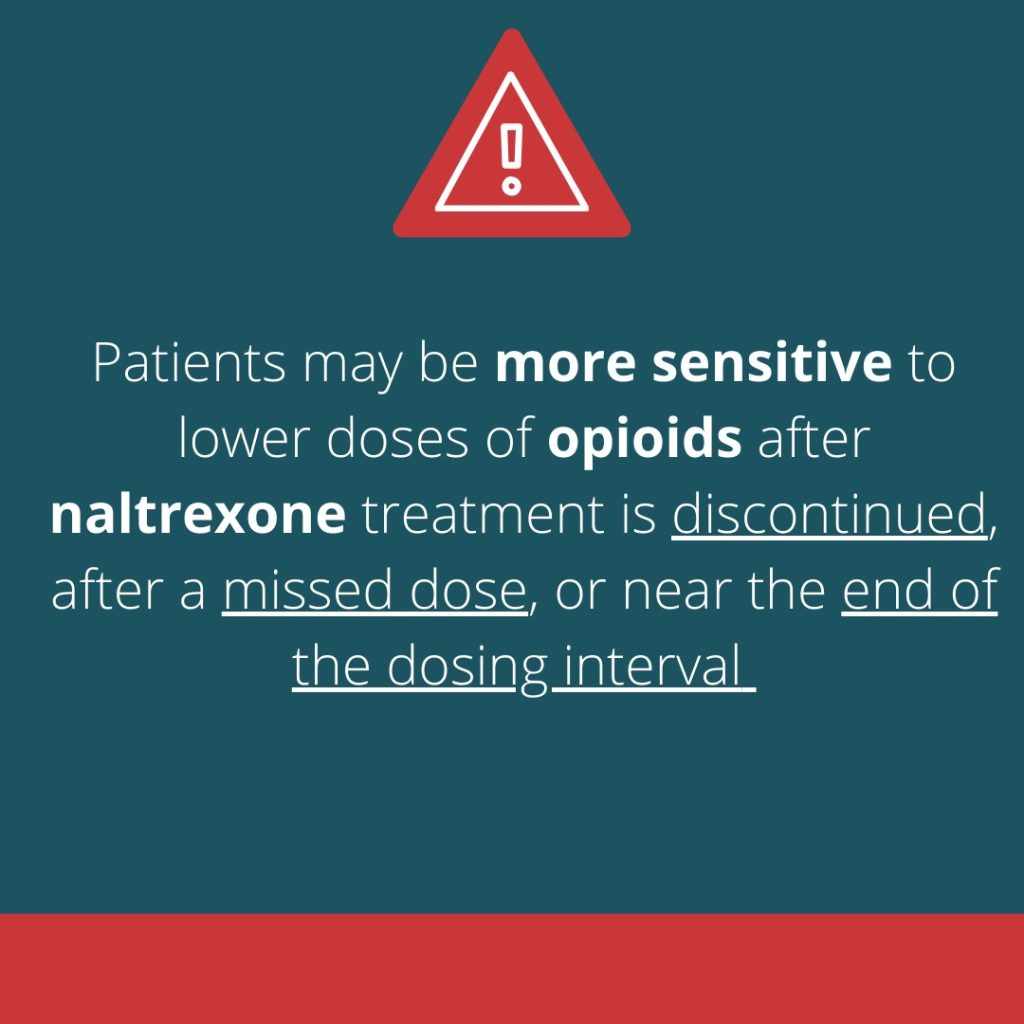

Patients should be opioid-free for a minimum of 7 to 10 days before taking naltrexone (14).

Prescribers must be aware that patients who have been treated with naltrexone may respond to lower opioid doses than previously used, which could result in potentially life-threatening or fatal opioid intoxication. Patients should be educated that they may be more sensitive to lower doses of opioids after naltrexone treatment is discontinued, after a missed dose, or near the end of the dosing interval (17).

Opioid withdrawal may be noted in patients, and symptoms include pain, hypertension, sweating, agitation, and irritability; in neonates: shrill cries and failure to feed (17).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you explain the major uses of naltrexone?

- Can you describe the recommendations for missed doses of naltrexone?

- What are some potential side effects?

- How does the mechanism of action for this drug explain the reversal benefits of opioids?

Long-Term Advocacy in the Opioid Addiction Crisis

Long-term advocacy measures for addressing the opioid addiction crisis involve comprehensive strategies that focus on prevention, treatment, recovery, and policy reforms. These strategies require coordinated efforts across various sectors, including healthcare, policymakers, law enforcement, and community organizations.

Long-term advocacy measures:

- Expansion of Treatment and Recovery Services

- Increased Access to Treatment: Increasing access to evidence-based treatment options, including medication-assisted treatment (MAT), inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation, and mental health services.

- Policy and Legislative Reforms