NIH Stroke Scale and Neuro Assessment

Contact Hours: 2

Author(s):

Maureen Sullivan-Tevault, RN, MS, BSN, CEN, CDCES

Course Highlights

- In this NIH Stroke Scale and Neuro Assessment course, we will learn about benefits and challenges with using the NIHSS assessment tool.

- You’ll also learn NIHSS scoring as it relates to treatment options.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of abnormal client assessment findings during a cranial nerve assessment.

Introduction

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), approximately 795,000 people in the United States have a stroke every year. Strokes may occur at any age, although the risk of a stroke increases with age.

This single neurological event is the leading cause of long-term disability. It heightens the risk of additional health complications, often in conjunction with the long-term burdens of rising medical costs, decreased quality of life, and shortened life spans.

Stroke treatment protocols are activated based on the time of onset, location, type, and severity of the stroke. The use of approved, standardized assessment tools streamlines these treatment protocols and facilitates rapid communication between all levels of providers.

The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) is the gold standard for rapid stroke assessment and intervention. Accompanied by various ongoing neurological assessments, the client who had a stroke is afforded the best treatment guidelines.

This course will overview various assessments of the client who had a stroke and discuss treatment options, as well as prevention strategies for future risk reduction (specific to stroke risk reduction, although applicable to various chronic health conditions).

Definition

The NIHSS (National Institutes of Health) Stroke Scale was developed in 1989 and consists of a 15-item impairment scale. Each item is scored, with the final score range of 0-42 points. The NIHSS scores reflect the clinical outcomes when used to evaluate strokes.

Total scores below 4 indicate favorable outcomes, while scores above 21 indicate severe strokes. NIHSS scores of greater than 22 are at greater risk of hemorrhagic conversion if given the tPA (tissue plasminogen activator) protocol. (3,4,5)

Ask yourself...

- Are you familiar with the NIHSS at this time?

- Have you had the opportunity to use this assessment tool at your place of employment?

- If yes, what are your concerns with this assessment tool?

- The NIHSS was developed in 1989. Prior to that, what areas of concern might have existed in the care of a stroke client?

NIHSS Overview

NIHSS Scoring and Interpretation

The objective scoring of the NIHSS may determine the severity of a stroke. As the total scores may range anywhere from 0 to 42, the following ranges reflect stroke severity and are often used to guide treatment protocols. (6,7)

Scores as follows:

| Total Score | Severity of Stroke | Treatment Options Regarding rTPA for Arterial Ischemic Strokes |

| 0 | No stroke detected | Not indicated |

| 1-4 | Minor stroke suspected | Not indicated |

| 5-15 | Moderate stroke suspected | IV TPA may be considered for disabling symptoms (4.5 window of opportunity) |

| 16-20 | Moderate to severe stroke is suspected | EVT TPA may be considered for NIHSS >6(12-hour window of opportunity) |

| 21-42 | Severe Stroke suspected | >25 NIHSS is considered inappropriate due to the high risk of conversion to cerebral hemorrhage. |

Ideally, the NIHSS is completed in less than 10 minutes and is considered an objective, formal method to assess the severity of a stroke.

The NIHSS is routinely performed at various stages throughout the acute care of a client who is experiencing a stroke, as well as during stages of the client’s ongoing rehabilitation and recovery (8):

- Initial evaluation (and ongoing at various timed intervals) in the emergency department setting

- Before the initiation of any reperfusion therapy (to have a baseline score with which to evaluate the effect of the therapy)

- During reperfusion treatment, usually at timed intervals (for example, every 2 hours x 24 hours, then every 4 hours ongoing throughout the hospital stay)

- Ongoing neurological assessments per plan of care

- Anytime the client’s current neurological condition has changed

Ask yourself...

- The NIHSS can be used anytime the client’s neurological condition has changed.

- What signs and symptoms would indicate a change in a person’s neurological condition?

- Although this is a “stroke” assessment scale, what other conditions might affect a person’s neurological status?

- Have you seen the NIHSS used to assess clients who have not had a stroke?

- If so, did the NIHSS adequately reflect the changes in the client’s condition?

- What other nursing assessments have you used to evaluate your(non-stroke) client’s neurological status?

NIHSS Assessment

The NIHSS measures a client’s brain function and includes an assessment of the following abilities (9):

- Level of consciousness

- Visual ability

- Sensation ability (detecting touch)

- Independent movement (movement upon verbal request)

- Capacity of speech and language

NIHSS Benefits and Challenges

The reliability/validity of the NIHSS is challenging when the acute neurological client has the following situations: these “outliers” that affect the overall scoring must be considered and documented appropriately so as not to influence treatment options negatively.

- The existence of any language barrier (including, but not limited to, foreign languages and sign language)

- Previous/preexisting neurological deficits (include previous stroke, as well as known traumatic brain injuries)

- The client is currently on a ventilator/ intubated/sedated per protocol

Ask yourself...

- If your clients experiencing a stroke speak a foreign language, what contingency plans (options) are in place at your facility to assist you in your nursing assessment?

- Based on the emergency treatment timeline involved in acute stroke care, are these options easily accessible in a timely fashion?

- Would you consider using family members for translation purposes in this emergency setting (if no other translator methods are available)? If so, how would you document this unique situation and best communicate it to other healthcare team members?

The NIHSS relativity is highly regarded in the treatment and stabilization of acute neurological injuries due to the following reasons:

- The assessment form is objective and standardized, which allows all healthcare providers to streamline treatments and monitor client progress.

- The assessment total scores have been proven to predict the accuracy of the projected stroke outcomes and can thus be used to navigate post-stroke management guidelines.

- The NIHSS has high inter-rater reliability, meaning that various healthcare professionals (in multiple clinical practices) are using the forms and obtaining similar scores, which adds another layer of consistency to the stroke management care continuum.

- The NIHSS offers versatility; it has been successfully used in research studies, clinical trials, and even virtual/ telehealth settings to accurately assess a client who had a stroke and align them with the most appropriate treatments.

See the attached NIHSS sample.

The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) is a 15-item neurological examination that evaluates several areas that may be affected by an acute stroke.

- Level of consciousness (is the client alert, oriented, and able to follow a simple command?)

- Best gaze (can the client follow an object with their eyes?)

- Visual field (is the client able to see things there are not in their direct field of vision/ placed directly in front of them?)

- Facial palsy (is the client able to move their facial muscles appropriately?)

- Motor arm (can the client hold their arm up without drifting for 10 seconds; does the arm drift downwards toward the bed?)

- Motor leg (can the client hold their leg up at a 30-degree angle for at least five seconds; does the leg fall toward the bed?)

- Limb ataxia (can the client touch their finger to their nose; can they run their heel down their shin on each side?)

- Sensory (does the client react/ can they feel a pinprick to their face, arms, trunk of their body, and their legs?)

- Best language (how does the client express themselves; can they express their ideas without difficulty?)

- Dysarthria (does the client have any slurring of their speech?)

- Extinction and inattention (is the client aware/ attentive to their current environment?)

Ask yourself...

- Regarding the areas of evaluation in the NIHSS, what other conditions could affect a person’s level of alertness or ability to follow a simple command?

- If the client’s family is present during your client assessment, what questions would you ask them about the client’s normal levels of alertness and abilities?

- If your client has a history of paraplegia, what areas of the NIHSS would be affected? How would you adequately reflect this alteration (change) in scoring?

- If your client has a history of a previous stroke, what areas of the NIHSS might be affected? How would you adequately convey this pertinent history to the care team members?

- If your client has preexisting vision/ visual field defects, how would you document this finding on your nursing assessment? Does your facility have special accommodations for visually impaired/ visually challenged clients?

Language Assessment Tools in Stroke Scale

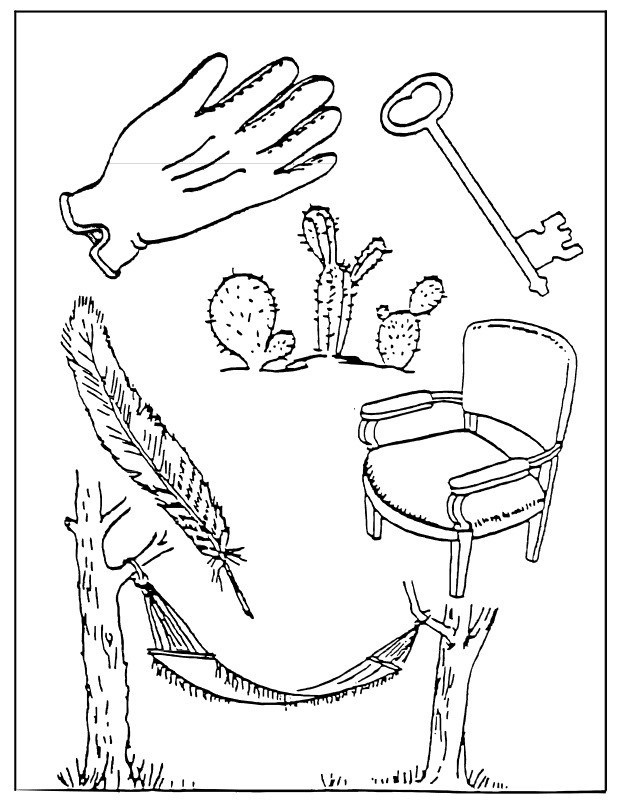

In addition to the physical assessment part of the NIHSS, four pages of images and words further determine the location and extent of a stroke.

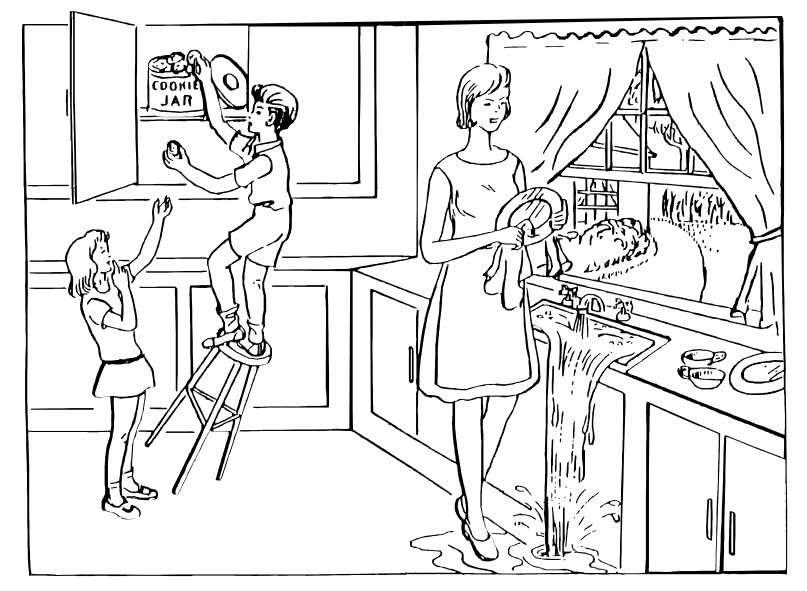

At first glance, these images and words may not “make sense” when viewed objectively. They do, however, provide critical insights into the location and severity of the suspected stroke. The following is a brief overview of each section.

In the first two images, there are a series of objects. The client is asked to describe (name) each object. In doing so, the client is evaluated in several areas: cognition, communication, and language deficits.

The drawback of this section is that there are concerns that variables such as client age, demographics, and geographical location may affect outcomes in this area. For example, depending on where the client has lived, they may have never even seen cacti. The feather in the image is described as a bird feather and a feather writing quill. The glove has been described as a glove and a mitten.

In the “kitchen” image, several objects and situations occur. The client is asked to describe what they see. The simple identification of objects, as well as the scenarios occurring (“the sink is overfull and flooding; the boy is about to fall off the stool”), allows for further assessment of a client’s speech, object identification, and ability to comprehend (and articulate) the various occurrences in the image.

Image 1. NIHSS Language Assessment “Series of objects” image

Image 1. NIHSS Language Assessment “Series of objects” image

Image 2. NIHSS Language Assessment “Kitchen scene” image

Image 2. NIHSS Language Assessment “Kitchen scene” image

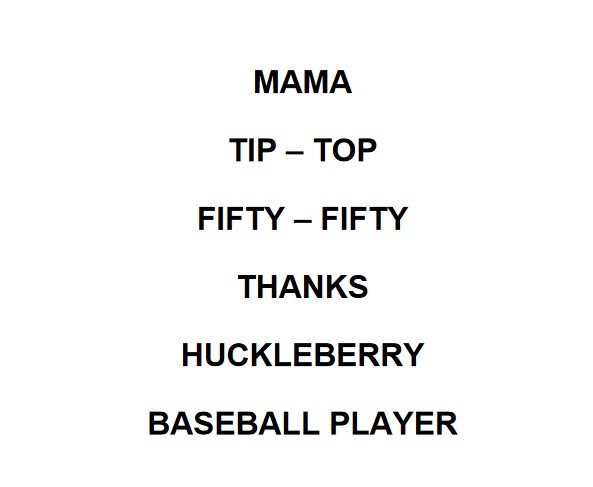

The following two photos are the most recent updates to the NIHSS. These updates/ new additions in objects were found to be more contemporary and less biased in content than previous samples when tested among healthy research participants (regardless of their age, sex, ethnicity, or demographics). (10,11)

Image 3. NIHSS Language Assessment updated images (10,11)

Image 3. NIHSS Language Assessment updated images (10,11)

Ask yourself...

- As mentioned, the two black-and-white images above show the recent changes in the NIHSS. Look at the images closely. Do you see any areas that might be confusing to your client?

- Do you feel that the contents of these two images are more recognizable to most people?

- What objects in these images may have more than one meaning?

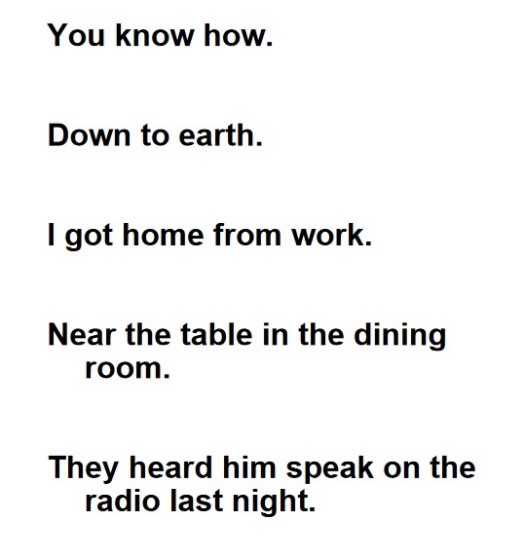

Ability to Communicate

In the following two sections, the client is asked to read the words and sentences out loud (see images 4 and 5). Several assessments are occurring as the client reads the words. The purpose of the words and fragmented sentences is to assess for potential injury to the brain’s speech center. These words and sentences are unrelated and are not meant to represent a story. They challenge speech comprehension and the ability to form words (thus evaluating muscle function related to speaking). The assessments occurring are an evaluation of comprehension and language ability (and may also further evaluate a suspected injury to the visual field (vision loss/partial or full vision field loss). (12)

The abnormal findings

- Loss of language ability (can the client actually form the words/ read them out loud and read them in order?)

- Loss of comprehension (can the client perform the requested task?)

- Aphasia/ dysphagia assessment (comprehension of words being read; ability to read words; guessing and questioning of words)

- Anarthria/ dysarthria assessment (difficulty in actually forming words/ speaking due to injury of the muscles used to communicate; slurring of words)

Image 4. NIHSS Speech comprehension and communication challenge: Random words

Image 4. NIHSS Speech comprehension and communication challenge: Random words

Image 5. NIHSS Speech comprehension and communication challenge: Fragmented sentences

Neurological Assessment

Components of a Neurological Assessment

A neurological examination assesses a client’s motor and sensory skills, reflexes, and nerve function. In addition, this examination can also test for balance and coordination as well as overall mental status.

The extent of a neurological examination can be affected by many factors, including (but not limited to) preexisting comorbid conditions, acute illness or injury, and the client’s chronological age. In written form, these factors must be acknowledged within the assessment findings to not negatively impact outcomes based on “total scores” (such as the NIHSS stroke scale). (13)

A neurological examination may be done for any of the following reasons:

- During routine physical examinations, annual wellness and preventive screenings

- To evaluate the progression of a known neurodegenerative condition

- To assess the extent of injury after acute trauma (concussion, stroke)

- To evaluate any new onset of changes in balance, behavior, coordination, mood, or cognition

The following areas will be evaluated during a neurological examination, dependent on presenting symptoms and medical complaints:

- Mental status examination, to include level of alertness, orientation to surroundings, ability to communicate, speech patterns

- Motor function, balance, coordination, symmetry in strength

- Sensory perception to touch, temperature

- Reflex evaluation

A neurovascular assessment, in comparison, is done when there is a concern regarding a compromised blood flow to an area. Such compromise, left untreated, could lead to permanent injury or death.

Neurovascular assessments are often used to assess injuries of the musculoskeletal system (limb extremities fractures, including crush trauma injuries). Still, they can also be utilized in various cases, including spinal surgery, complicated plastic surgery, and even the (nonsurgical) placement of a plaster cast. (14)

The “6 Ps” of a neurovascular assessment are as follows:

- Pain-pain extent and location

- Paresthesia-numbness or tingling of extremity

- Pulselessness-absence of the pulse (by palpation with secondary assessment by Doppler if necessary)

- Pallor-paleness or discoloration of skin

- Paralysis-inability to move the extremity

- Poikilothermia- skin temperature (inability to maintain core body temperature)

Cranial Nerve Assessment

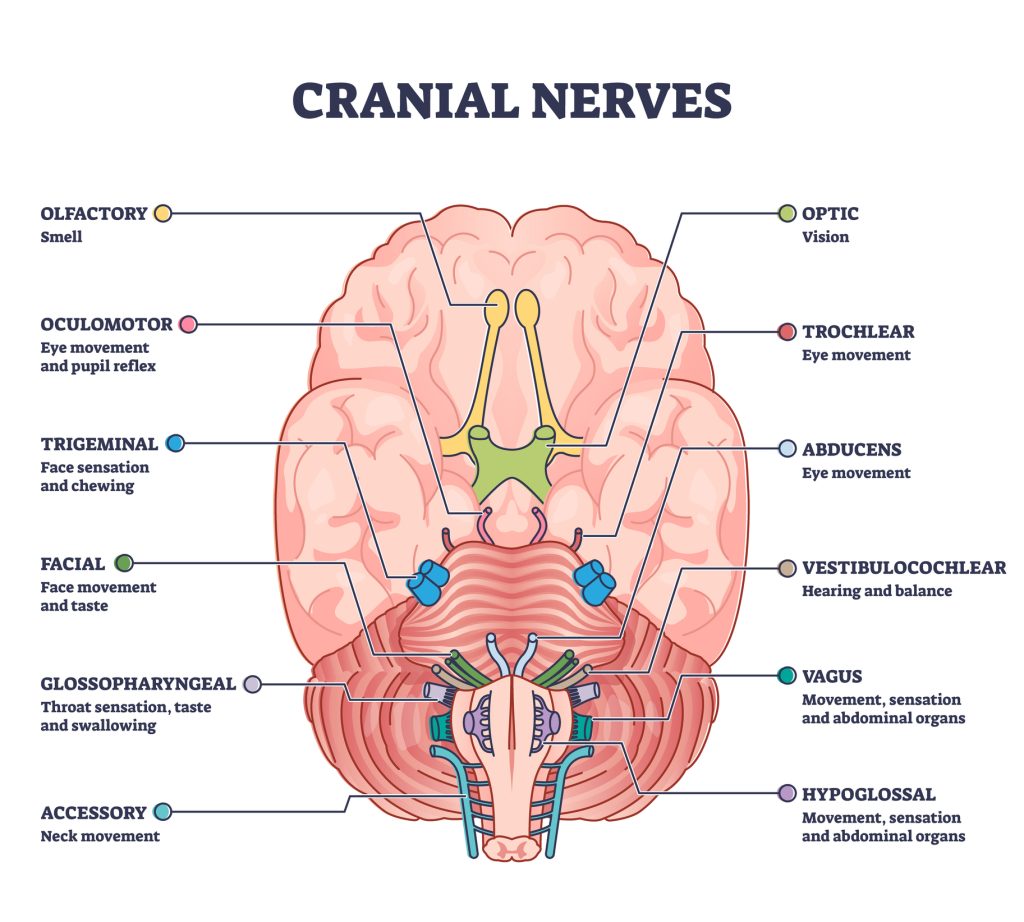

There are twelve sets of cranial nerves. They send electrical impulses (signals) from your brain to other body parts, including your face, head, neck and torso. These impulses are responsible for both sensory and motor functions. (15,16)

Two sets of cranial nerves (the olfactory and the optic nerve) are located in the cerebrum, the largest part of the brain, and are positioned above the brain stem. The remaining ten sets of cranial nerves are located in the brain stem and connect with the spinal cord. (15,16)

The twelve cranial nerves are as follows:

| Cranial Nerve | Name | Function |

| 1 | Olfactory Nerve | Involved in the sense of smell |

| 2 | Optic Nerve | Involved in vision |

| 3 | Oculomotor Nerve | Involved in the spontaneous opening and moving of eyes and appropriate adjustments of pupil width (dilation/ constriction). |

| 4 | Trochlear Nerve | Involved in eye movement, such as looking down and moving your eyes toward your nose or away. |

| 5 | Trigeminal Nerve | Involved in sensations in the eyes, most of the face, and inside the mouth, including normal chewing of food. |

| 6 | Abducens Nerve | Eye movement from left to right |

| 7 | Facial Nerve | Facial muscles, facial expressions, and sense of taste on the part of the tongue |

| 8 | Vestibulocochlear Nerve | Involved in hearing and balance. |

| 9 | Glossopharyngeal Nerve | Involved in taste sensation, muscles for swallowing, and saliva production |

| 10 | Vagus Nerve | Involved in regulating many automatic bodily functions, including normal digestion, blood pressure and heart rate stability, respiratory patterns, saliva production, and mood. |

| 11 | Accessory Nerve (also known as Spinal Accessory Nerve | Involved in shoulder and neck movement. |

| 12 | Hypoglossal Nerve | This nerve controls tongue movement and is involved in many activities, including speaking and swallowing food and fluids. |

Ask yourself...

- The involvement of cranial nerve pathology greatly increases the risk of client injury during a hospital stay. Your client has CN 8 involvement. His sense of balance and hearing ability are being affected. What additional safety measures should be in place to lower the risk of injuries while being evaluated in the emergency department?

- The client is experiencing severe vertigo at this time, as well as significant tinnitus. What additional nursing interventions could be done to ensure client safety, as well as comfort?

- When this client is ready to be transferred to the stroke unit, what additional information should be conveyed in the nurse-to-nurse report? Are there any additional nursing recommendations regarding the room assignment/ client placement?

Two well-known mnemonics for remembering the names of the cranial nerves in order: (17)

On old Olympus/s towering top, a Finn and German viewed some hops.

Ooh, ooh, ohh to touch and feel very good velvet. Such heaven. (or alternate ->Ah, Heaven) (S= Spinal accessory; A= Accessory)

Cranial Nerve Testing, Clinical Signs/Symptoms, and Pathology of Abnormal Findings

- CN1. Olfactory Nerve: This nerve is tested to assess a client’s sense of smell. Cover one nostril while assessing the ability to smell/detect a smell with the unobstructed nostril, then repeat the process on the other nostril. The loss of smell, known as anosmia, may occur as the result of certain (non-neurological) infections or allergies, as well as due to the presence of nasal polyps. A reduced sense of smell, known as hyposmia, however, is considered a common symptom in early Parkinson’s disease, as well as some lesions located at the base of the skull (such as a meningioma, which is a slow-growing tumor). (18,19,20)

- CN 2. Optic Nerve: Testing of this nerve will involve assessing both visual acuity and visual fields, with each eye being tested separately. The pupillary light reflex (how the pupil reacts to having light shined into it) will evaluate the ability to constrict, and a fundoscopic examination will evaluate the actual optic disk. (18,19,20)

Papillary edema and retinal hemorrhages can indicate increasing intracranial pressure and brain hemorrhage while the failure of pupils to react appropriately to light may indicate lesions of the optic nerve pathway. Monocular blindness and cuts in the visual field may indicate pseudobulbar neuritis or pressure resulting from a pituitary tumor. (18,19,20)

- CN 3, 4, and 6 Oculomotor, Trochlear, and Abducens Nerves: These three cranial nerves are all involved in eye muscle movement. The client is asked to follow the hand movements of the evaluator with only their eyes as they draw an invisible letter “H” in front of them. Abnormal findings would range from a disconjugate gaze (eyes moving in different directions), involuntary eye movements (side to side or up and down), and double vision. The inability to perform this task may indicate a wide variety of conditions, ranging from increasing intracranial pressure, brain infarct, and even optic neuritis, suggestive of early Multiple Sclerosis. (18,19,20)

- CN 5 Trigeminal Nerve: Assessment of this nerve involves asking the client to clench their jaw. As this nerve is involved in the ability to bite and chew (mastication), a noted weakness of this muscle would indicate possible nerve inflammation/ impairment. This nerve also supplies the sensation to the face, so sensory deficits in touch may indicate further assessment of the possibility of nerve inflammation. (18,19,20)

- CN 7 Facial Nerve: Assessment of this nerve involves asking the client to perform several movements, such as raising their eyebrows, closing their eyes very tightly, smiling, and blowing up (puffing out) their cheeks. Deficits/ nerve impairment or inflammation are suspected when there is weakness on one side of the face or the lower half of the face. Symmetry should be noted on both sides of the face. (18,19,20)

- CN 8 Vestibulocochlear Nerve: This nerve is assessed by whispering words behind the client and rubbing fingers or hair together close to the client’s ears. The client should be asked if they can hear the sounds/ whispered words. If a hearing deficit is suspected, further testing can be used to differentiate between sensorineural hearing loss and conductive hearing loss. (18,19,20)

- CN 9 and 10 Glossopharyngeal and Vagus Nerve: this nerve is assessed by actively listening to the client’s speech and checking for hoarseness of voice or nasal speech. A swallow test can also be done, and the client is observed for any coughing or gurgling speech after swallowing sips of water. The client should also be asked to open their mouth wide and say “ah.” At the same time, the provider observes for any asymmetry of the palatal arch (and deviation of the uvula to one side versus its usual centered position). (18,19,20)

A swallow test is a standard assessment of a client with a suspected stroke. It involves having the client take sips of water and observing for difficulty in swallowing. Many facilities keep the client “NPO” until a swallow test is performed. (18,19,20)

- CN 11 Spinal Accessory Nerve: Assessment of this nerve is done by asking the client to turn their head to each side, against the provider’s hand’s resistance, and shrug their shoulders. The accessory nerve provides movement to muscles in the neck and shoulder, as well as to structures in the throat, including the larynx. (18,19,20)

- CN 12 Hypoglossal Nerve: Assessment of this nerve involves inspection of the tongue inside the mouth, as well as asking the client to stick out their tongue. This cranial nerve is involved in the motor component of the tongue, which involves speech, swallowing, and chewing of food. (18,19,20)

Ask yourself...

- What stroke protocols (treatments) need to be changed/held/adjusted if the client fails the initial swallow test?

- How is adequate nutrition provided if the client is unable to swallow safely?

- What additional consultations may be ordered if the client continues to have difficulty swallowing?

Cranial Nerve Palsies

The term palsy indicates a paralysis of a cranial nerve, which results in some element of muscle weakness and movement irregularities.

The following examples offer a brief overview of some cranial nerve palsies.

- Oculomotor palsy, or third nerve palsy, is a condition in which one eye stays positioned/ fixed, giving the appearance that the client is looking down or out to the side.

- Trochlear nerve palsy, or fourth nerve palsy, is a condition that causes vertical double vision and difficulty for the client in attempting to look downward.

- Trigeminal neuralgia is a condition that affects the fifth cranial nerve and can cause severe facial pain, similar to electrical shocks.

- Abducens nerve palsy, also known as sixth nerve palsy, is a condition that causes strabismus (or misalignment of the eyes) and double vision.

- Facial nerve palsy, or Bell’s palsy, is a condition affecting the facial nerve and usually results in temporary drooping of one side of the face.

Cranial nerves pair with anatomical sensory functions in the outline diagram. Labeled educational collection with neurology brain system and how nerve relay information to human body vector illustration.[/caption]

Cranial nerves pair with anatomical sensory functions in the outline diagram. Labeled educational collection with neurology brain system and how nerve relay information to human body vector illustration.[/caption]

Ask yourself...

- Your client presents to the Emergency Department with one-sided facial weakness/drooping. What nursing observations/ findings did you assess that led you to believe this client has Bell’s Palsy versus a stroke?

- How is the initial treatment for Bell’s palsy different from stroke? (or is it?)

- Your client presents to the Emergency Department with complaints of “double vision”.

- What nursing functions do you perform in your initial assessment?

- What client complaints regarding their double vision would heighten the suspicion that a stroke has occurred?

- Conversely, what client complaints would lower the suspicion that a stroke has occurred?

Babinski Reflex

The Babinski Reflex was discovered by neurologist Joseph Babinski in 1896.

The Babinski reflex (also known as the plantar reflex) is a normal reflex present in infants and children roughly up to the age of two years old (although it may disappear within the first year of life). The reflex is absent in adults. (21,22)

In evaluating for a Babinski reflex, the examiner will firmly stroke the sole of the foot, which should cause the big toe to move upward or toward the top surface of the foot while the other toes fan out. The occurrence of this reflex in an adult indicates some level of dysfunction (damage) of the brain or spinal cord. (21,22)

A normal / negative Babinski sign (in an adult) would be the toes curling downward during the testing or the foot remaining still.

A positive Babinski sign (in an adult) would be the big toe lifting and the other toes spreading out.

If an adult tests positive for a Babinski sign, it indicates there is damage to some aspect of the central nervous system that controls movement. The following conditions may “test positive” for the Babinski sign: (21,22)

- Brain tumors

- Meningitis

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Alzheimer’s dementia

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS or Lou Gehrig disease)

- Strokes

- Spinal Cord Injury

Acute Stroke Management

Emergency Treatment for Acute Stroke

Emergency stroke treatment interventions, based on initial and ongoing NIHSS, type of stroke and client stability, and preexisting medical conditions, may include the following (23,24,25):

- Activase tissue plasminogen activator thrombolytic (tPA) IV (intravenous) within the first 3 hours of stroke onset or

- Activase tissue plasminogen activator thrombolytic (tPA) IA (intraarterial) within 3-6 hours of stroke onset for anterior circulation stroke infarct

- Craniotomy to remove blood clots, halt hemorrhagic bleeding, and reduce intracranial pressure increases through coiling, endovascular embolization, and surgical clipping of aneurysm.

- Blood pressure stabilization measures (client-specific)

- Secondary prevention measures (client-specific)

For more information on Activase (tPA) administration, click on the following (healthcare professional) website: https://www.activase.com/ais/dosing-and-administration/dosing.html

Self-Management Strategies

In a very generic sense, unrelated to any specific neurological condition, the following self-management behaviors are recommended for any/all clients who have experienced (or are living with) the conditions mentioned above. As many neurology-based health conditions are chronic and manageable but not curable, the self-management guidelines pivot from traditional care plans aimed at restoring a client back to “former self” (pre-illness status) to maximizing current abilities/ stabilization (“the new normal”). (26,27)

Self-management behaviors:

- Medication adherence/ compliance to manage symptoms

- Monitoring symptoms and reporting changes in health to client care provider team to reduce risk factors

- Lifestyle assessment and modifications as indicated (proper nutrition, routine physical activity, sleep hygiene practices, stress management)

- Physical activity/therapy to maintain current mobility and strength

- Mental health support groups and counseling services as indicated for client/ family members

- Interdisciplinary healthcare team to monitor disease progress, reduce risk factors, preventive wellness examination, and routine medical care

- Meaningful and purposeful goals that add quality to daily life (these will be client-specific, such as maximal independence stabilization of disease process)

- Ongoing education regarding the normal progression of a disease process, including end-of-life services when applicable

Secondary Stroke Prevention / Risk Reduction

The following are secondary prevention guidelines to treat the underlying causes of strokes (to lower the risk of recurrent stroke) (28). In stroke-specific cases, a dedicated focus on reducing the risk of recurrent stroke should also be made.

Guidelines that should be taken into consideration:

- Antihypertensive therapies (preexisting history of hypertension)

- Hyperlipidemia therapies (statin therapies in high-risk individuals)

- Hyperglycemia therapies (preexisting diabetes medical condition)

- Physical inactivity therapies (preexisting lifestyle behaviors versus post-stroke limited mobility)

- Proper nutritional therapies (to address any preexisting metabolic conditions {prediabetes, diabetes, metabolic syndrome} as well as to maintain optimal nutrition post-stroke)

- Lifestyle behavioral assessment and intervention. If the client has a history of alcohol and nicotine usage prior to stroke, client should be assessed for possible substance withdrawal in the acute phase of rehabilitation (and treated accordingly)

- Antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies if applicable (*may be contraindicated in cases of hemorrhagic stroke conditions)

Ask yourself...

- Your client is ready for discharge to home, accompanied by his family members. He has suffered an ischemic stroke that has left him with right-sided weakness in his arm and leg. He is right-handed dominant. What home health follow-up services should be considered in his rehabilitation?

- What additional services should be considered if the client lived alone?

- What questions could you ask this client to ascertain his specific recovery goals?

- Are there any questions you could ask the family members that might help you determine whether outside referrals are necessary?

- What community resources are available in your area to assist in post-stroke rehabilitation?

Research

According to the American Heart Association, which released an overview of both heart disease and strokes in 2024, “strokes account for approximately 1 in every 21 deaths in the United States, with a person dying from a stroke every 3 minutes 14 seconds”.

Despite advances in medicine occurring worldwide, this potentially catastrophic “event” continues to increase in strength. Thus, so does the ongoing research to find ways of improving detection, lowering risks, and positively influencing health outcomes. (29,30)

The NIH Stroke Net, created by NINDS, is a data management center linked to over 500 stroke hospitals in the United States alone. It conducts research studies and clinical trials in all facets of stroke management, from the acute phase to rehabilitation therapies.

Landmark trials included the DEFUSE 3 Trial, which improved outcomes in stroke management by showing the benefits to clients who received thrombectomies up to 16 hours after the onset of a stroke. Another funded trial was the MISTIE all trial, which pioneered using TPA with minimally invasive surgery to remove stroke-causing clot formation. (29,30)

For more information on the above-mentioned clinical trials:

Conclusion

The treatment of neurological clients is indeed complex. The need for objective data collection, free of bias and evaluator self-interpretation, is detrimental in determining treatment throughout the stroke care continuum (from emergency care to rehabilitation and beyond).

The development of neurological assessment tools, such as the NIHSS, affords all levels of healthcare professionals the skillset to collect necessary assessments in a streamlined fashion and communicate these findings in universally acceptable terms (“NIHSS score is…..”) to all members of the client’s medical team.

The NIHSS certification is offered through the professional education hub at the American Heart Association. For more information, check the following link:

https://education.heart.org/productdetails/nih-stroke-scale-test-group-a

References + Disclaimer

- Hasan, T. F., Hasan, H., & Kelley, R. E. (2021). Overview of acute ischemic stroke evaluation and management. Biomedicines, 9(10), 1486. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9101486

- Stroke Facts. (2024, May 15). Stroke. https://www.cdc.gov/stroke/data-research/facts-stats/index.html

- NIH Stroke scale. (n.d.). National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/stroke/assess-and-treat/nih-stroke-scale

- NIH Stroke Scale/Score (NIHSS). (n.d.). MDCalc. https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/715/nih-stroke-scale-score-nihss#next-steps

- Zhuo, Y., Qu, Y., Wu, J., Huang, X., Yuan, W., Lee, J., Yang, Z., & Zee, B. (2021). Estimation of stroke severity with National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale grading and retinal features. Medicine, 100(31), e26846. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000026846

- Kogan, E., Twyman, K., Heap, J., Milentijevic, D., Lin, J. H., & Alberts, M. (2020). Assessing stroke severity using electronic health record data: a machine learning approach. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-019-1010-x

- Hasan, T. F., Hasan, H., & Kelley, R. E. (2021b). Overview of acute ischemic stroke evaluation and management. Biomedicines, 9(10), 1486. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9101486

- Ames, H. (2023, March 28). Stroke scale: What is it and what is its purpose? https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/stroke-scale#:~:text=A%20doctor%20typically%20performs%20the,help%20them%20decide%20on%20treatment.

- Vega, J., MD PhD. (2023, September 7). The NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS). Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/nih-stroke-scale-evaluation-3146092

- NIH Stroke Scale Updated with New Visual Stimuli. (2024, March 1). National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/news-events/news/highlights-announcements/nih-stroke-scale-updated-new-visual-stimuli

- Stockbridge, M. D., Kelly, L., Newman-Norlund, S., White, B., Bourgeois, M., Rothermel, E., Fridriksson, J., Lyden, P. D., & Hillis, A. E. (2024). New picture stimuli for the NIH stroke scale: a validation study. Stroke, 55(2), 443–451. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.123.044384

- Admin. (2024, August 9). NIH Stroke Scale | STROKE MANUAL. STROKE-MANUAL. https://www.stroke-manual.com/nihss-stroke-scale/#1664270571988-a01c69b5-b617

- Neurological exam. (2019, November 19). Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/neurological-exam

- Guo, L. (2022, January 18). Neurovascular assessment: what is it, why it’s performed, and more. Osmosis by Elsivier. Retrieved October 23, 2024, from https://www.osmosis.org/answers/neurovascular-assessment#:~:text=What%20are%20the%206%20Ps,paralysis%2C%20pulselessness%2C%20and%2

- Shahrokhi, M., & Asuncion, R. M. D. (2023, January 16). Neurologic exam. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557589/

- Professional, C. C. M. (2024, August 19). Cranial nerves. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/21998-cranial-nerves

- Thomas, A. (2024, July 1). How to remember the 12 cranial nerves: tips & mnemonic tricks. Simple Nursing. https://simplenursing.com/how-to-remember-cranial-nerves-easily-with-mnemonics/

- Shahrokhi, M., & Asuncion, R. M. D. (2023b, January 16). Neurologic exam. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557589/

- Dellwo, A. (2023, July 17). The anatomy of the accessory nerve. Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/accessory-nerve-anatomy-4783765#:~:text=The%20accessory%20nerve%20provides%20motor,referred%20to%20as%20CN%20XI.

- Kim, S. Y., & Naqvi, I. A. (2022, November 7). Neuroanatomy, cranial nerve 12 (Hypoglossal). StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532869/

- Babinski reflex: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. (n.d.). https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003294.htm#:~:text=The%20Babinski%20reflex%20occurs%20after,up%20to%202%20years%20old.

- Professional, C. C. M. (2024b, August 20). Babinski Reflex (Plantar Reflex). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/babinski-reflex-plantar-reflex

- Admin. (2024a, January 3). Intra-arterial thrombolysis | STROKE MANUAL. STROKE-MANUAL. https://www.stroke-manual.com/intra-arterial-thrombolysis-iat/#:~:text=intra%2Darterial%20thrombolysis%20(IAT),to%20treat%20distal%20embolization%20(incl.

- Faan, J. L. S. M. F. (n.d.). Thrombolytic therapy in stroke: ischemic stroke and neurologic deficits, clinical trials, thrombolysis guidelines. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1160840-overview#:~:text=As%20a%20result%2C%20intra%2Darterial,onset%20in%20the%20posterior%20circulation.

- Stroke – Diagnosis and treatment – Mayo Clinic. (n.d.). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/stroke/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20350119#:~:text=Emergency%20IV%20medicine.,TPA%20is%20appropriate%20for%20you.

- Kılınç, S., Erdem, H., Healey, R., & Cole, J. (2020). Finding meaning and purpose: a framework for the self-management of neurological conditions. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(2), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1764115

- FRCPath, G. G. M. P. F. F. (2024, August 5). MS Self-Management: What does it mean? Neurology Live. https://www.neurologylive.com/view/ms-self-management-what-does-it-mean

- American Heart Association, Inc. (2021). 2021 Guideline for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients with Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack [Press-release]. https://www.stroke.org/-/media/Stroke-Images/Infographics/PreventingAnotherStroke2021-Guidelines.pdf

- Research. (n.d.). National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/stroke/research

- Martin, S. S., Aday, A. W., Almarzooq, Z. I., Anderson, C. A., Arora, P., Avery, C. L., Baker-Smith, C. M., Gibbs, B. B., Beaton, A. Z., Boehme, A. K., Commodore-Mensah, Y., Currie, M. E., Elkind, M. S., Evenson, K. R., Generoso, G., Heard, D. G., Hiremath, S., Johansen, M. C., Kalani, R., . . . Palaniappan, L. P. (2024). 2024 Heart Disease and stroke statistics: A report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 149(8). https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000001209

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback!