Nursing Interventions for Acute Pain Management

Contact Hours: 3

Author(s):

Nicole Galan MSN, RN

Course Highlights

- In this course, we will learn about the different nursing interventions for acute pain and why nurses must understand each one.

- You’ll also learn the basics of opioid medications and why they should be used with caution.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of how to manage patients’ pain effectively.

Introduction

Pain is one of the most common reasons people seek care in a hospital and one of the most distressing symptoms of hospitalized patients. It is also directly linked to a patient’s satisfaction with their care: people are more likely to report being unhappy with their care if they had unrelieved pain during their stay (24).

Most importantly, it is our job as nurses and healthcare providers to help relieve the pain and suffering of the people in our care. There are legitimate concerns about the overuse and addictive nature of opioid pain relievers, and thankfully, there are many alternative options. These non-opioid nursing interventions for acute pain management include non-opioid pain relievers, complementary techniques, and non-medication strategies (17).

Nurses must regularly assess pain and collaborate with both the patient and provider to ensure that timely access to adequate pain relief is a priority of their care.

Prevalence of Acute Pain

Acute pain is a significant problem for hospitalized patients and has been identified as a priority in providing quality and effective care. In addition, pain management has been recognized by the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) project for nurses as a core competency under Patient-Centered Care (28). This is important because if not properly treated, pain can cause anxiety, depression, reduced healing, fatigue, non-compliance with treatment, and more extended hospital stays 912). Pain is also costly in other ways, such as causing decreased productivity, income, and quality of life (11).

Despite knowing the potential consequences of poor pain relief and having multiple modalities available as nursing interventions for acute pain, many patients are still inadequately managed for pain during hospitalization.

A 2019 study reviewing pain management in patients with chronic pain in an outpatient setting found that 77% of patients reported a negative pain management index (16). Another study found that patients over-report pain to increase provider responsiveness to their pain relief (4).

This is because many barriers still exist that prevent patients from being treated appropriately for their pain. These potential barriers include (1,22):

- Lack of knowledge or skills about nursing interventions for acute pain management

- Heavy nursing workload or lack of time

- Provider concerns about causing tolerance or addiction

- Patient fears of side effects or addiction

- Insufficient provider orders or time to pre-medicate patients before painful procedures

- Providers focus on treating pathophysiology, rather than managing pain or other symptoms

- While all healthcare providers should aim to reduce a patient’s pain, nurses are in the unique position to make a difference with individual patients and system-wide pain management protocols.

Ask yourself...

- Think about the last time you were in pain. In addition to the physiological pain sensation, what other feelings did it invoke?

- What potential barriers to adequate pain relief that you’ve observed in your practice?

- How many nursing interventions for acute pain are you aware of?

- How many nursing interventions for acute pain have you used in your practice?

- How has the prevalence of pain changed since you started practicing?

Pathophysiology of Pain

There is no set definition of pain, but it is commonly defined as an unpleasant experience, usually related to underlying tissue damage or injury. Pain is a subjective experience and one that very much depends on the person experiencing it. What one person experiences as pain, another person may experience as a minor discomfort, and another may experience it as (19).

It is a complex sensation, the experience of which involves the interaction of three different systems (6,19,25).

Sensory/Discriminative System

The actual sensation of and reaction to pain are sent through sensory and afferent nerves, the spinal cord, and the brain stem. This system causes the body to try to remove itself from the source of the pain.

Motivational/Affective System

A person’s learned approach/avoidance behavior concerning pain occurs through the interaction of the brain stem, the reticular formation, and the limbic system.

Cognitive/Evaluative System

A person’s learned behavior towards the pain experience, including appropriate (and inappropriate) pain behaviors. This learned behavior can block or increase a person’s perception of their pain.

Anatomy and Physiology of Pain

The nervous system is the primary body system responsible for the experience and interpretation of pain. The four main steps involved in this process are transduction, transmission, perception, and modulation (5,8,15).

Step 1: Transduction

The process of transduction begins with the afferent pathway, which is responsible for the actual detection of pain. Nociceptors are pain receptors found at the end of small afferent neurons that detect noxious stimuli, which include changes in temperature, pressure, and other mechanical or chemical stimuli. These nociceptors are found deep in the skin, muscles, tendons, and subcutaneous tissue and produce a large variety of different – and not all unpleasant – sensations. These can range from a cool breeze to a pleasant massage to cutting, crushing, and burning sensations.

When these receptors are activated, they release chemical mediators, such as prostaglandins, substance P, serotonin, histamine, bradykinin, and potassium. Among other functions, these mediators generate an action potential by exchanging sodium and potassium at the cell membrane and activating and sensitizing the nociceptors to further stimulation by the stimuli.

Step 2: Transmission

The sensation travels along A- and C-nerve fibers to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. A-nerve fibers are lightly myelinated (insulated in a protein and fatty acid substance known as myelin, which allows nerve impulses to travel faster), while C-nerve fibers are unmyelinated. The thicker the nerve fiber (and myelin coating), the quicker the nerve impulses will travel. The table below shows the different types of these fibers and the sensations they detect. Nerve impulses travel the fastest among the A-alpha and A-beta fibers and slowest along the A-delta and C-nerve fibers (32).

| Characteristics of Afferent Nerve Pathways | ||

| Afferent Nerve Fibers | Sensation | Conduction Velocity (m/s) |

| A-alpha | Proprioception (the body’s position in its environment) and motor strength | 13-22 |

| A-beta | Light touch | 16-100 |

| A-delta | Pickling pain and temperature (cold) | 5-30 |

| C | Pain, temperature (warmth), itch, and autonomic function | 0.2-2 |

Once these nerve signals reach the spinal cord, excitatory neurotransmitters cross the synaptic cleft to the nociceptive dorsal horn neurons (NDHN). The neurotransmitters involved in this process include (33):

- Substance P

- Nitric oxide

- Bradykinin

- Glutamate

- Adenosine triphosphate

From here, the nerve impulse travels up the spinal cord to the thalamus, where they are sent to different areas in the brain for processing.

Step 3: Perception

Pain perception translates all this nerve activity into a conscious and actual experience for the patient. Several different areas of the brain and the central nervous system facilitate this.

Reticular Formation Tracts

Reticular formation tracts are responsible for the recognition of and response to pain. For example, if you step on a tack, the reticular formation track recognizes the painful stimulation and causes you to move your foot quickly. This area is also responsible for the alert and attentive feeling of pain.

Limbic System

The limbic system also plays a key role in the unpleasant emotional and behavioral response to pain and actions taken to reduce it.

Thalamus

The thalamus acts as a switchboard, helping to direct the pain signal to the different locations in the brain. Some parts of the thalamus also direct the motor, behavioral, and emotional responses when painful stimuli occur.

Somatosensory Cortex

The somatosensory cortex comprises two distinct regions in the brain’s parietal lobe that are responsible for receiving and processing sensory information from all over the body. This region gets information about painful stimuli and identifies the location, intensity, and type of pain. It also connects the current pain sensation with previous experiences with pain.

Step 4: Modulation

Modulation is the final step in the pain pathway. This process changes the pain impulse transmission in the spinal cord due to the descending modulatory pain pathways (DMPP). Endogenous hormones and substances are found within this pathway and help to either block pain signal transmission or increase it. Inhibitory neurotransmitters help to block the transmission of pain nerve impulses to relieve pain and include (31):

- Acetylcholine

- Oxytocin

- Serotonin

- Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)

- Norepinephrine (noradrenaline)

- Neurotensin

- Endogenous opioids, such as enkephalins and endorphins

Excitatory neurotransmitters increase the transmission of pain to the brain and are usually responsible for the increased mental alertness and cognition associated with a painful event.

The Gate Control Theory is one of the most familiar theories of pain modulation. Under this theory, gates are found throughout the spinal cord. When these gates are open, pain messages can get through to the central nervous system, making the pain feel worse. Factors like stress, tension, anxiety, boredom, and lack of physical activity can all help open those gates and worsen pain sensations (27).

On the other hand, when those gates are closed, fewer pain messages get through to the central nervous system, reducing the pain experience. Factors that help to close the gates include feeling relaxed, regular exercise, distraction, certain medications, and other types of stimulation (such as massage, heat, ice, or acupuncture). This theory often explains why non-medication nursing interventions for acute pain can be so effective (27).

Ask yourself...

- Why might distraction be an effective form of pain management for some people?

- How can anxiety and fear worsen a person’s experience of pain?

- Does understanding the pathophysiology of pain help you to understand the rationale behind different nursing interventions for acute pain?

- How does the Gate Control Theory explain why non-medication nursing interventions for acute pain are effective?

- How does pain impact the sensory system?

- What are the 4 main steps of the pain process?

- What is the afferent nerve system?

Classification of Pain

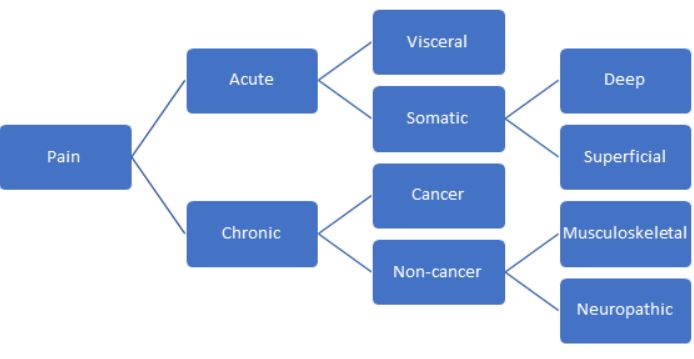

Pain can be classified based on duration, location, quality, and intensity. Understanding these different types of pain can help the medical and nursing team plan appropriate nursing interventions for acute pain management. The figure below shows the organization and classification of these different types of pain.

Duration of Pain

One of the most common and important distinctions about pain is its duration. Based on duration, there are two classifications of pain: acute and chronic.

Acute

Acute pain is short-term pain that lasts less than three months. It is usually associated with a specific insult or injury, such as a broken leg, a ruptured appendix, or even childbirth. In most cases, once the cause is addressed and treated, the pain subsides. Acute pain is often described as sharp, stabbing, or burning. There are many effective nursing interventions for acute pain [19].

Chronic

Chronic pain, however, is far more complex. Chronic pain is pain that has lasted longer than three months or past the expected healing time from an injury or illness. Headaches, fibromyalgia, and arthritis are all examples of this type of pain. Chronic pain can be described as sharp or intense, but it can also be described as dull, aching, or burning.

In addition, chronic pain often has a psychological or emotional component, causing anxiety, insomnia, depression, and a decrease in a person’s ability to perform everyday tasks. This type of pain is much more challenging to treat and can severely interfere with a patient’s quality of life [19].

Location

Pain can also be classified based on its location. Any of these categories can classify both acute and chronic pain.

Visceral Pain

Visceral pain arises from the internal organs in the abdomen and pelvis, such as the intestines, female reproductive organs, kidneys, and liver. This type of pain is often described as diffuse, and it is usually difficult to isolate where it is coming from. One reason for this is referred pain, where the pain is experienced in a location different from the actual injury. Think about having left arm and shoulder pain during a heart attack.

While the internal organs are mostly immune to injuries like lacerations or burning (short of a catastrophic injury), they are more likely to cause pain by inflammation, ischemia (death of tissue), and stretch (like overdistended intestines). Visceral pain is often described as pressure, dull, throbbing, or aching [3]

Somatic Pain

On the other hand, somatic pain is experienced in the skin, muscles, bones, and joints. While visceral pain is diffuse, somatic pain is usually well-localized, and it is easy to determine where it comes from. It is generally described as sharp, stabbing, aching, or burning. Somatic pain can result from an injury, such as a paper cut, or an illness like arthritis or bone cancer.

Somatic pain can be further categorized as deep or superficial, depending on where the injury occurs [3]

Deep Pain

Deep somatic pain comes from structures deep within the body, such as bones, muscles, tendons, and joints.

Superficial Pain

Superficial somatic pain comes from structures closer to the body’s surface, like the skin and mucus membranes.

Location

Pain can also be classified based on its location. Any of these categories can classify both acute and chronic pain.

Visceral Pain

Visceral pain arises from the internal organs in the abdomen and pelvis, such as the intestines, female reproductive organs, kidneys, and liver. This type of pain is often described as diffuse, and it is usually difficult to isolate where it is coming from. One reason for this is referred pain, where the pain is experienced in a location different from the actual injury. Think about having left arm and shoulder pain during a heart attack.

While the internal organs are mostly immune to injuries like lacerations or burning (short of a catastrophic injury), they are more likely to cause pain by inflammation, ischemia (death of tissue), and stretch (like overdistended intestines). Visceral pain is often described as pressure, dull, throbbing, or aching.

Somatic Pain

On the other hand, somatic pain is experienced in the skin, muscles, bones, and joints. While visceral pain is diffuse, somatic pain is usually well-localized and easy to determine where it is coming from. It is generally described as sharp, stabbing, aching, or burning. Somatic pain can result from an injury, such as a papercut, or an illness like arthritis or bone cancer.

Depending on where the injury occurs, somatic pain can be further categorized as deep or superficial.

Deep Pain

Deep somatic pain comes from structures deep within the body, such as bones, muscles, tendons, and joints.

Superficial Pain

Superficial somatic pain comes from structures closer to the body’s surface, like the skin and mucus membranes.

Ask yourself...

- What is visceral pain?

- What is the difference between superficial and somatic pain?

- What is deep pain?

- What type of pain do you feel or see most often in practice?

- What is the difference between visceral pain and deep pain?

Pathophysiology

The last main way to classify pain is based on its cause or pathophysiology. There are three types of pain in this category: nociceptive, neuropathic, and psychogenic (19).

Nociceptive Pain

Nociceptive pain comes from an injury to the body tissues and is the type of pain that most people are familiar with. It can be acute, chronic, visceral, or deep pain. It covers many kinds of injuries or illnesses, from simple paper cuts or stubbing a toe to arthritis or cancer pain (19).

Nociceptive pain is usually responsive to changes in the environment: shifting position, applying ice or a heat pack, or elevating the injured site.

Neuropathic Pain

Neuropathic pain arises from damage to the neurons in the peripheral or central nervous system. Are you familiar with the tingling associated with hitting your funny bone? That’s neuropathy: you’ve hit and temporarily injured the large nerve that runs through the elbow. Other common causes of neuropathies include multiple sclerosis, diabetic neuropathy, and even phantom limb pain (19).

Unfortunately, neuropathic pain doesn’t respond well to changes in the environment and is more likely to develop into chronic pain. Damaged neurons or nervous tissue don’t heal quickly or easily.

Nociplastic Pain

Nociplastic pain is a pain for which no readily identifiable underlying cause can be found and is attributed to psychological factors. Common conditions contributing to nociplastic pain include fibromyalgia, tension headaches, and irritable bowel syndrome (19).

This definition of pain has drastically changed over the past several years. Despite this changing definition, we do know that depression, anxiety, and other psychological problems can interact with pain, particularly chronic pain. Depression, anxiety, and other factors can worsen pain, and ongoing pain can significantly worsen associated psychological symptoms. As nurses, we should be mindful of and sensitive to these types of issues

Ask yourself...

- How could an untreated neuropathy develop into a chronic pain condition?

- How does understanding pain classification lead to more effective and patient-centered nursing interventions for acute pain?

- How could the nurse support a patient with a psychogenic pain disorder?

- What is the difference between nociceptive pain and neuropathic pain?

- What is nociplastic pain?

Performing a Pain Assessment

One of the most important nursing interventions for acute pain management is regular assessment of the patient’s pain and the effectiveness of their pain management plan.

There are two main components of a pain assessment: a health history/interview and a physical exam.

Health History and Interview

Assuming that you are working with an established patient, you don’t need to complete a full history or patient interview, but you should touch upon the relevant clinical factors about their pain. If this is a new admission or a new patient, you will need to perform a comprehensive initial history and assessment first.

The PQRSTU mnemonic can help you remember all the different points you should hit during the interview to assess the characteristics of their pain. The table below shows the important questions that you should ask about a patient’s pain (9,21).

| PQRSTU Pain Assessment Questions | |

| Factor | Questions to Ask |

| Provoking/palliating factors |

|

| Quality/quantity |

|

| Radiating |

|

| Severity |

|

| Timing/treatment |

|

| Understanding/you |

|

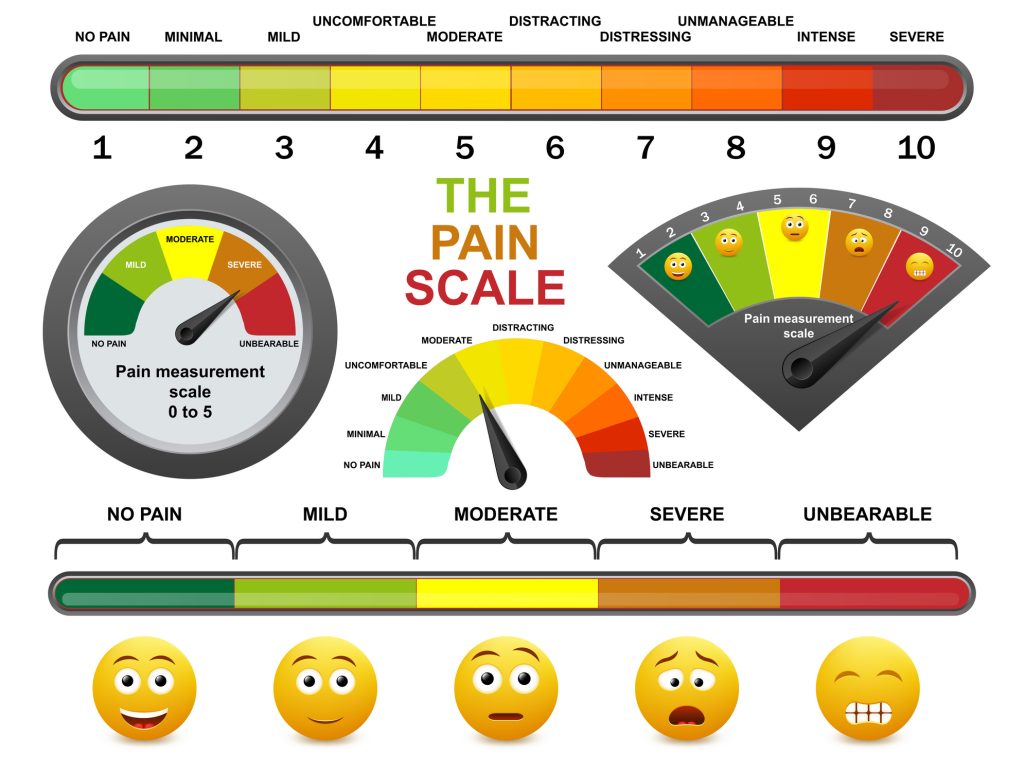

Pain Scales

Pain scales are valuable for nurses to assess and rate patients’ pain. Several scales can be used in different clinical situations, and it is up to the nurse’s judgment to determine which one to use [30].

Number Rating Scale

This is the most common pain scale that most people are familiar with. It is appropriate for adults (or older children) who are alert, oriented, and responsive. Ask the patient to rate their pain on a scale from one to ten, with one being no pain and ten being the worst pain they’ve ever had.

Wong-Baker FACES

This pain scale is very commonly used for children aged three and older. It uses six pictures of faces, ranging from a face without pain to a face with a lot of pain. To use it, the child is asked to pick which face represents their feelings.

FLACC

The FLACC scale is used for young children between the ages of 0 and 2. It stands for Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, and Consolability. The nurse assesses each of these characteristics and assigns a score from zero to two. These scores are added together for a total score between zero and ten. The higher the number, the higher the patient’s pain is assumed to be.

CRIES

The CRIES scale is also used for young infants over or equal to 38 weeks of gestational age. This scale is similar to the FLACC scale in that the nurse evaluates the infant based on five characteristics, assigning a score of zero to ten. The scores are totaled, where a score greater than 6 indicates the need for analgesia. The characteristics used by this scale are the presence of a high-pitched cry, the requirement of oxygen to maintain oxygen saturation above 95%, increased blood pressure and pulse, facial expression, and sleeplessness.

CPOT

The CPOT (Critical Care Pain Observation Tool) was developed for critically ill patients who may not be able to verbalize their pain. It is similar to the CRIES and FLACC scales: four different criteria are assessed from zero to two, with a maximum score (indicating the most pain) of eight. The domains used in this scale include facial expression, body movements, muscle tension, and compliance with mechanical ventilation (in intubated patients) or vocalization (in non-intubated patients).

Please note that this is not a comprehensive list of all available pain scales. When appropriate, you should defer to your institutional policies.

The patient should be assessed frequently, especially if they are having pain or receiving pain medication. The nurse should also ask about associated signs and symptoms: insomnia, nausea, vomiting, shortness of breath, itching, etc. Make sure to evaluate the effectiveness of the nursing interventions for acute pain by reassessing the pain level after administering analgesia or other non-pharmacological interventions.

The nurse must never forget that pain is what the patient says, regardless of their body language. If the patient states that their pain is a level 7, but is laughing and hanging out with family members, the nurse must document and act as if the pain level is a 7.

Ask yourself...

- Which tools does your institution use for pain assessment? What are the policies surrounding pain assessment?

- What would you do if the pain scale recommended by your institution does not apply to your current patient?

- Which questions would the nurse ask a patient to get more information about the quality of their pain?

- Why is it important to reassess pain after administering any nursing interventions for acute pain?

- Which pain scale do you find most effective?

- Which pain scale have you found most difficult?

- What barriers to the assessment of a patient’s pain have you encountered? How have you overcome those barriers?

- How does personal bias impact your ability to manage a patient’s pain?

Physical Exam

If appropriate, the physical exam should also be abbreviated and limited to what is relevant to the patient’s pain. Make sure to get a set of vital signs and then examine the area causing pain.

- Look for redness/swelling/warmth of the skin.

- If the pain is related to a recent surgical procedure, check out the surgical wound and surrounding tissue.

- If safe and appropriate, palpate gently to determine where the pain might be coming from.

- If the pain is in a joint or muscle, perform gentle range-of-motion exercises to determine what movements trigger it.

- If the pain is new, notify the provider if it signals a change in status.

Ask yourself...

- What questions would you ask, and which exam techniques would you use if a 12-year-old child presents to the emergency department after falling off a bicycle?

- How should you document a patient’s pain level if their stated pain score differs from their behavior or appearance?

- Which physical symptom have you found most telling when assessing a patient for pain?

Non-Pharmacological Nursing Interventions for Acute Pain

For patients with mild pain, non-pharmacological nursing interventions for acute pain can sometimes be very effective. They can also work well in conjunction with pain medications and other nursing interventions for acute pain [18, 19].

Acupressure

Acupressure is a traditional Chinese modality that has been used for generations. By applying pressure to certain points on the body, it is believed that you can help restore the flow of energy and balance throughout the body. Though acupressure is mostly considered safe, some points should not be stimulated in pregnant women as they might stimulate labor. Press firmly and use an up-and-down or circular movement for several minutes. Make sure to stop or ease up pressure if the motion causes worsening pain or discomfort (18,19).

Acupuncture

Acupuncture is also a traditional Chinese modality that has recently gained popularity in the United States and other Western countries. It is believed that the insertion of small needles into the skin at specific points helps to stimulate endorphin release and trigger other pain-relieving changes in the brain. The needles are left in place for 10 to 30 minutes at a time so the patient can rest. The needles are then removed, and the treatment is repeated several times. Acupuncture is quite safe but should only be performed by a licensed practitioner. Research about effectiveness is mixed, but it may be worth a try for patients with complicated or chronic pain (18,19).

Aromatherapy

Essential oil use is an ancient therapeutic modality that dates back hundreds of years and has gained popularity in recent years. It involves the absorption of essential oils through the skin or olfactory system to reduce pain, nausea, muscle tension, anxiety, and depression (18, 19).

Distraction

Distraction is an effective and simple nursing intervention for acute pain. Remember the gate theory of pain? Distraction is one of those factors that can help close the pain gates, reducing the experience of pain. The presence of strong sensory input can help a person be unaware of their pain (18,19).

Music

Music therapy works similarly to distraction. It gives the person something else to focus on apart from their discomfort. When using this nursing intervention for acute pain, the nurse must remember to let the patient select the type of music they prefer (18,19).

Heat

Applying a heating pad or hot water bottle may stimulate the closure of the pain gates, reducing pain and discomfort. It may also stimulate the release of endorphins, which also relieve pain. The patient should be reminded not to lie directly on the heat source due to the risk of burns. If the nurse applies the heating pad, the site should be reassessed frequently to reduce the possibility of injury (18,19).

Cold

Applying a cold or ice pack works similarly. Cold can relieve inflammation and pain and promote healing. It works best over inflamed joints. Like applying heat, the nurse must carefully and frequently assess the patient’s skin to ensure that injury does not occur and remove the ice if the patient feels numbness, aching, or burning. Ice can be particularly effective before a needle puncture or injection (18,19).

Guided Imagery

This nursing intervention for acute pain involves the nurse sitting close to the patient and helping them create a calming and relaxing image in their mind. The nurse speaks quietly, assisting the patient in concentrating on the image and relaxing (18, 19).

Massage

Massage is a great technique for soothing tense muscles and promoting relaxation and sleep. Touch stimulation may trigger the release of endorphins or help close the pain gates responsible for pain transmission (18, 19).

Biofeedback

Biofeedback is a type of behavioral therapy taught to the patient over several weeks. It allows the patient to visualize physiological responses and eventually learn to control them. This technique is particularly beneficial for people with headaches or muscle tension (18, 19).

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS)

This technique uses a special device that produces a mild electrical current through the skin via external electrodes. The machine makes a buzzing or tingling sensation, the intensity of which can be controlled by the patient in response to the pain they are feeling. This treatment requires a physician’s order, and the nurse should help the patient with hair removal before applying the electrodes (18,19).

Ask yourself...

- How should the nurse respond to a patient who refuses pharmacological pain medication in favor of alternative nursing interventions for acute pain?

- What is the best response by the nurse if a patient’s family is encouraging him or her to only use non-pharmacological nursing interventions for acute pain?

- What method should the nurse suggest for a patient with frequent tension headaches?

- How does guided imagery help to relieve pain and promote comfort and relaxation?

- How many of these nursing interventions for acute pain have you used on patients or yourself in the past?

Analgesics as Nursing Interventions for Acute Pain

For patients with pain that does not respond to non-pharmacological measures, analgesics may be more effective. There are three types of pain medication:

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and non-opioids

- Opioids or narcotics

- Adjuvants

Non-Opioid Analgesics

Non-opioid analgesics can be used to treat mild to moderate pain and are often combined with opioid pain relievers to enhance their effectiveness. The two common types of drugs in this category are cyclooxygenase inhibitors and acetaminophen.

Cyclooxygenase Inhibitors

Cyclooxygenase inhibitors are mainly subdivided into nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and aspirin. Cyclooxygenase, or COX, is an enzyme in the pathway to synthesize prostaglandin, a key inflammatory hormone-like substance, from arachidonic acid. When produced, prostaglandins have several effects on their target organs and contribute to nociceptive pain.

There are two types of COX enzymes: COX-1 and COX-2. COX-1 is found primarily in the gastric mucosa, kidneys, and blood vessels. Inhibition of this enzyme is believed to contribute to renal toxicity and gastrointestinal effects. COX-2 enzymes are activated by the processes causing pain, fever, and inflammation (29).

Selective COX-2 inhibitors were introduced as an alternative to non-selective COX-1/COX-2 inhibitors to reduce the gastric side effects of COX-1 inhibition.

However, the drugs were quickly linked with some potentially serious cardiovascular safety concerns, including myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident, and other thromboembolic diseases. Most of these medications were removed from the market, and the FDA recommended limiting the use of celecoxib (Celebrex), the remaining selective COX-2 inhibitor (29).

Salicylates, like aspirin, are non-selective COX inhibitors. They also inhibit platelet aggregation, block pain impulses, and may act on the hypothalamus to reduce fever and pain. The table below shows selected medications from the COX inhibitor class of drugs (29).

| Properties of Selected Cyclooxygenase Inhibitor Drugs | ||||

| Drug | Class | Adult Dosage | Indications | Adverse Effects |

| Acetylsalicylic Acid (Aspirin) |

Salicylates | 650mg q4-6h |

|

|

| Ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil) |

Propionic Acid Inhibitor and Non-selective inhibitor of COX-1 and COX-2 | 400-800mg q6-8h |

|

|

| Celecoxib (Celebrex) |

Selective COX-2 inhibitor | 100-200mg once or twice daily |

|

|

| Diclofenac (Voltaren, Cataflam) |

Acetic acid derivative | 50mg 3-4 times a day |

|

|

| Ketorolac (Toradol) |

Acetic acid derivative | 15-30mg IV/IM q6h

10mg PO q4-6h |

|

|

| Naproxen (Naprosyn, Aleve) |

Propionic Acid Inhibitor and Non-selective inhibitor of COX-1 and COX-2 | 250-500mg PO twice daily |

|

|

(29)

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen is thought to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis in the central nervous system. It also reduces fever and inflammation less effectively than the COX inhibitors. It is used to treat mild to moderate pain and can also be used as a fever reducer. Dosing in children depends on their age and weight, but in adults, the dose is typically 650mg every 4 hours or 1,000mg every 6 hours, with the maximum daily dose not exceeding 4g per day. Patients with a history of liver failure should not exceed 2g per day (13).

Acetaminophen is metabolized in the liver, but larger doses can accumulate a hepatotoxic metabolite that can build up and cause liver damage. Hepatotoxicity is the primary adverse effect of acetaminophen, and the nurse should carefully counsel patients to be aware of hidden sources of the drug in cold medicine and other combination products (13).

Acetaminophen overdose is a medical emergency and is often fatal secondary to hepatotoxicity. There are four phases of acetaminophen overdose:

- Phase 1 – Occurs within the first 2 to 24 hours after ingestion.

- The patient experiences symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, sweating, abdominal pain, and diarrhea.

- Phase 2 – Occurs 24 to 72 hours after ingestion.

- The patient may feel better, though right upper abdominal pain often persists. Serum liver enzymes, bilirubin, and prothrombin time begin to rise.

- Phase 3 – Occurs 72 to 96 hours after ingestion.

- Symptoms begin to reappear, including nausea/vomiting, jaundice, confusion, and coma. Even more dramatic rises in liver enzymes and other markers will be present.

- Phase 4 – Occurs 6 to 7 days after ingestion.

- Liver enzymes begin to trend back towards normal, and hepatic damage may start to resolve. However, depending on the amount of acetaminophen ingested, the treatment, and the extent of liver damage that occurs, complete hepatic failure and death are possible.

The treatment for acetaminophen overdose includes gastric lavage, administration of activated charcoal, and acetylcysteine every 4 hours (started within the first 8 hours after ingestion) for 18 doses. Acetylcysteine interferes with the formation of hepatotoxic metabolites. In addition to administering medication and providing supportive care, the nurse must follow plasma acetaminophen levels (13).

Ask yourself...

- Why is there an increased risk of gastric ulcer in people taking COX inhibitors?

- What side effects are associated with the use of acetylsalicylic acid?

- What NSAID would be most appropriate for a patient with rheumatoid arthritis pain?

- What medication would the nurse recommend for a patient with menstrual cramps?

- What provider orders would the nurse anticipate for a patient with a suspected acetaminophen overdose?

Opioid Pain Management

Opioid pain relievers are a nursing intervention for acute pain that is usually reserved for cases of severe pain, such as cancer or post-surgical pain, or moderate pain that is not well-controlled with other types of drugs. This class of medication acts directly on receptors in the central nervous system in a few different ways. For example, they block transmission of nociception from the peripheral nerves to the spinal cord, change the activity of the limbic system in the brain, and modulate the descending inhibitory pathways in the spinal column to prevent transmission of pain signals.

There are three types of opioid receptors: mu, kappa, and delta, and drugs are classified based on their response to these receptors.

- Pure Agonists bind directly to mu receptors to relieve pain

- Partial Agonists work similarly to pure agonists but don’t produce the same complete response as pure agonists. The analgesic effect will not increase as the dosage increases, but the potential for side effects does.

- Mixed Agonists—Antagonists act as agonists to produce analgesia at the kappa receptors but as antagonists at the mu receptors.

- Antagonists bind to receptors and competitively block other opioids from binding there.

Morphine sulfate is the prototype opioid prescribed for pain and the drug against which the other opioids are compared. It is the drug of choice for cancer patients and is often used for other types of moderate to severe pain. In addition to producing analgesia, morphine has several other clinically beneficial effects, including reduction of the emotional response to pain, suppression of the cough reflex, reduction of cardiac workload, and reduction of anxiety. Because of this, morphine is an effective nursing intervention for acute pain management (7,14).

In addition to morphine, there are many other options for opioid pain relievers. The table below shows some common drugs in this class of medication.

| Properties of Selected Opioid Pain Relievers | |||

| Pure Opioid Agonists | |||

| Drug | Indication | Administration | Nursing Considerations |

| Morphine (Roxanol, MS Contin, Astromorph, Kadian, Avinza) |

|

|

|

| Codeine (Tylenol #2, #3, or #4) |

|

|

|

| Hydrocordone (Lortab, Vicodin)

|

Treats moderate to severe pain |

|

|

| Oxycodone (OxyContin)

|

|

|

|

| Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) |

|

|

|

| Fentanyl (Sublimaze, Duragesic) |

|

|

|

| Meperidine (Demerol) |

|

|

|

| Levorphanol (Levo-Dromoran) |

|

|

|

| Methadone (Dolophine, Methadose) |

|

|

|

| Partial Agonists | |||

| Drug | Indication | Administration | Nursing Considerations |

| Buprenorphine (Buprenex) |

|

|

|

| Buprenorphine + Naloxone (Suboxone) |

|

|

|

| Mixed Agonists-Antagonists | |||

| Drug | Indication | Administration | Nursing Considerations |

| Butorphanol (Stadol) |

|

|

|

| Antagonists | |||

| Drug | Indication | Administration | Nursing Considerations |

| Naloxone (Narcan) |

|

|

|

(7,14).

Opioid medications do carry the risk of some serious side effects, which the nurse must monitor for. Potential side effects include [7]:

- Constipation

- Itching

- Respiratory depression

- Vertigo/lightheadedness

- Confusion

- Nausea/vomiting

- Hypotension

Due to their similar nature, many of the opioids produce identical effects to varying degrees. However, opioid antagonists are the exception and cause very different side effects, which can include (26).

- Nausea/vomiting

- Hypertension

- Dizziness

- Abdominal pain

- Insomnia

- Weakness

- Headache

- Muscle pain

There is also a risk of allergy, which can occur with any of the major opioid drugs, including morphine. The nurse must be especially careful of this risk and other adverse effects when administering opioids to an opioid-naïve patient.

Ask yourself...

- Which action would the nurse take if respiratory depression secondary to morphine is suspected?

- What signs and symptoms might suggest a morphine allergy?

- Why would Buprenex not be a good option for a patient with an opioid addiction?

- Meperidine should not be given to patients taking which medication due to the risk of hypertension?

- When considering opioids as one of the nursing interventions for acute pain, what factors should you consider?

Adjunct Analgesics

Adjunct or adjuvant drugs are the final type of medications used for analgesia. They are often combined with analgesics to enhance pain relief, but they are sometimes used on their own to manage specific types of pain. There are many different types of adjuvants, depending on the patient’s needs and clinical situation (2).

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are primarily used to manage acute and chronic cancer pain, pain due to spinal compression, and pain affecting the musculoskeletal system. Though the exact mechanism is unknown, corticosteroids are known to reduce swelling, inflammation, and edema. However, corticosteroids do cause some serious side effects, including hyperglycemia, increased susceptibility to infection, reduced immune system function, and suppression of adrenal function. Dexamethasone, prednisone, and methylprednisolone are the three most prescribed corticosteroids. Corticosteroid injections are one of the most common nursing interventions for acute pain management of arthritis and joint pain.

Antidepressants

A class of antidepressants, known as tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) can be used with opioid or non-opioid pain relievers to help relieve pain. They are most effective for neuropathic pain and may work by increasing the levels of serotonin and norepinephrine in the synaptic cleft, preventing the transmission of pain signals. Doses for TCAs tend to be lower when used to treat pain than the dose used to manage depression. The most common side effects are weight gain, loss of sexual desire, dry mouth, orthostatic hypotension, and urinary retention.

Antiepileptic Drugs

Antiepileptic or antiseizure drugs affect the central nervous system in several different ways and can reduce neuropathic pain. They modulate amino acids and neurotransmitters to reduce the transmission of pain signals between the periphery and the central nervous system. These drugs tend to be used for chronic pain disorders, such as diabetic neuropathy and fibromyalgia.

Antihistamines

Some antihistamines, particularly hydroxyzine, have been found to have analgesic, anxiolytic, and sedative properties that can be useful in patients with acute or chronic pain.

Local Anesthetics

Local anesthetics are an excellent option for well-localized pain, usually in the skin or superficial structures. Topical EMLA creams minimize pain due to venipuncture, intravenous line insertion, or other simple procedures. Lidocaine or prilocaine can be injected into the tissue to help with pain associated with invasive procedures, while patches can be used to manage post-herpetic lesions and neuropathies.

Alpha-2 Adrenergic Agonists

Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists may decrease the release of peripheral norepinephrine and work on the central alpha-2 adrenergic receptors, which may help reduce chronic headache and neuropathic pain. The drugs from this class that are most commonly prescribed for pain are clonidine and zanidine. Side effects are mild but may include dry mouth, orthostatic hypotension, and sedation.

GABA Receptor Agonists

More commonly known as muscle relaxants, GABA receptor agonists work best on neuropathic pain and muscle spasms. These drugs block the transmission of pain impulses and can decrease spasticity.

Finding a regimen that works may take time and trial and error. The nurse’s role in assessing and evaluating different nursing interventions for acute pain plays a crucial role in helping patients be as comfortable as possible. Most importantly, the nurse must advocate for patients struggling with pain management in the acute care setting.

Ask yourself...

- Which adjuvant would the nurse anticipate for a patient with chronic headaches?

- How do corticosteroids help to reduce pain?

- How would a nurse counsel a patient in pain about a new prescription for an antidepressant?

- Were you aware that antidepressants are used as one of the nursing interventions for acute pain?

Nursing Care of Patients Receiving Analgesia

The nursing care plan is an invaluable tool when caring for a patient with acute pain.

Assessment

The nurse should start with an assessment, as described earlier in this module. For a new complaint of pain, the nurse should perform a more comprehensive assessment: determine if there are other symptoms, ask about the characteristics of their pain (PQRSTU questions), and perform a physical examination as needed (9,21).

When caring for someone with known or expected pain, such as a post-surgical patient or after a broken ankle, the assessment could be more focused on the patient’s current pain level. Even in these situations, you should continue to perform a complete assessment at least once per shift or according to your institutional policies.

Report any new or unexpected complaints of pain or abnormal assessment findings to the provider and document them in the patient’s chart.

Identifying Goals and Planning

Based on the data identified during the assessment, the nurse will formulate goals and objectives to meet the patient’s needs. The primary goal for someone with acute pain is relief from that pain, but there may be other goals that are also appropriate. They may include (9,21):

- Improved physical mobility

- Improved self-care

- Decreased anxiety

- Improved rest and sleep

- Relief from analgesic side effects

Creating a concept map can be a useful tool for identifying potential problem statements and their relationships, as pain is often interrelated with other health problems.

Once goals are set, it is important to establish criteria against which the goals are measured. For example, you may identify that your patient will have a tolerable amount of pain upon discharge from the hospital. Your expected outcome may be that their pain level is consistently reported to be at a 4 or below.

A comprehensive pain management plan must consider the entire interdisciplinary care team. Did the medical provider enter orders for pain management medications? Are they appropriate? (For example, a simple acetaminophen order after a surgical procedure may not be sufficient to deal with post-surgical pain). Is the physical therapist planning to start mobility exercises to get the patient back on their feet? Does the patient want to speak with a clergy member to help focus on spiritual health? Is a pain management specialist needed? Having the appropriate team members in place makes it more likely that the patient will achieve the planned outcomes.

Implementation

Depending on the extent of the patient’s pain, you’ll use your nursing judgment to select and implement nursing interventions for acute pain to address it. For mild pain, non-pharmacological measures may suffice; for severe pain, regular administration of opioid pain relievers (as ordered) may be the best course of action. For these patients, it is important to stick with the scheduled doses as closely as possible because the pain becomes much harder to treat once it becomes severe.

Once the patient’s pain is under control, it is important to begin teaching and involving the patient in their care. The nurse should teach the patient non-pharmacological comfort measures, wellness strategies, and what to expect during the healing period. This information helps the patient become more capable of caring for themselves and promotes both physical and emotional healing.

Evaluation

Remember those expected outcome statements you created earlier in the planning stage? Well, now is when you’ll put them to use by comparing those expected outcomes to the actual outcomes experienced by the patient. The best way to evaluate patient outcomes is to ask the patient themself. Key questions could include:

- Are you still having pain?

- What is your current pain level?

- Have you experienced any side effects from your treatment?

- How is your pain limiting your ability to function or perform your activities of daily living?

- How is the treatment affecting your ability to perform daily activities?

- Are you able to rest?

- Are you able to eat comfortably?

And any other questions that could apply to the patient’s specific problem statement.

If the patient is unable to communicate, the family could also be a useful source of information. It is important for the nurse to explicitly ask these questions: some patients may not readily volunteer this information or be afraid to mention that they are still in pain or having side effects.

In addition to speaking with the patient (or family) directly, objective data can also provide useful information, particularly about potential side effects, such as oversedation or respiratory depression. The nurse should collect data, such as (9,21):

- Vital signs

- Level of consciousness

- Sedation

- Oxygen saturation

If the data suggests that the patient’s pain is under control and there are no bothersome side effects, then great! In this situation, you’ll continue to care for the patient according to the care plan and periodically evaluate the patient to ensure continued success.

If, however, the patient is still experiencing unacceptable amounts of pain or having side effects (whether they are dangerous or just uncomfortable), then the nurse will need to immediately make changes to the plan. This may include administering a second dose of medication, speaking to the provider about adding additional pain medication, adding alternative methods of pain management, discontinuing a medication that is causing side effects, and obtaining an order for a different option.

The nurse must continue to check in with the patient and provide reassurance and education about pain management. For example, if the patient complains that intravenous pain medication is not working 5 minutes after administration, the nurse should reassure the patient that the medication will have peak effectiveness at about 15 to 30 minutes, and they’ll check back then.

Ask yourself...

- How would the nurse document the pain assessment and evaluation for a patient receiving pain medication?

- What would the nurse do first when a patient complains that the IV morphine administered for post-operative pain control is not effective 45 minutes after administration?

- What action would the nurse take first if a patient is found to have a respiratory rate of 6 bpm at 1 hour after IVPB morphine administration?

- What information would the nurse include when teaching patients about their pain medication?

Nursing Interventions for Acute Pain in Special Populations

Pain management strategies may need to be adjusted when caring for certain populations. Three populations that will always need special consideration are infants and children, older adults, and people with a history of addiction.

Infants and Children

While the process is the same as with adult patients, assessment tools and treatments must be modified to work for the developmental ages of the young kids they are caring for. Pain scales like the FACES, FLACC, and other scales specifically designed for use in pediatric patients should be used when assessing for pain, and the nurse can also rely on input from the parents (9,21,30). As discussed earlier, these scales rely on the nurse’s observations of the child to determine pain level, rather than asking the child to describe their pain, which they may not be able to do.

Older children and adolescents are more likely to be able to verbalize their pain, making it more appropriate for the nurse to ask these kids directly.

When administering pain medication to children, especially infants or very young children, the nurse must be extremely careful when drawing up and administering intravenous medications. Some institutions may even require that a second nurse be present to review the order, medication label, prepared medication, and patient ID band before a narcotic is administered. Frequent assessments should be performed to reduce the risk of serious adverse reactions.

Older Adults

Age-related changes can influence not only a patient’s experience of pain but also how they metabolize pain medication. Older adults are more likely to have multiple health conditions, which can make the assessment process a bit more confusing. This would require the nurse to perform a more in-depth or comprehensive assessment to determine the source and type of pain that a patient is experiencing. In addition, the nurse must take a careful medication history, as they are at higher risk for side effects and drug interactions. Other factors that could increase a person’s risk for adverse effects include [10.:

- Slowing of gastrointestinal function, which slows the absorption rate of medications

- Decreased renal or hepatic function

- Decreased muscle, fat, and bone mass, which can lead to a higher risk of overdose

- Poor nutrition causes decreased albumin levels, which may be an issue with protein-bound drugs.

- Thinner skin, which can impact the absorption of topical medications

The nurse must be careful to take these factors into account when administering narcotics or other pain medications to an older adult and monitor them closely for side effects, adverse reactions, or drug interactions.

In addition, older adults may be more likely to have cognitive impairments, like Alzheimer’s disease or dementia, which could impact their ability to communicate or report their pain accurately. Again, the nurse must know these limitations and use the appropriate tools when working with this patient population [10].

Safety is also a major concern for this population, particularly when administering medications that can increase drowsiness, dizziness, or the risk of falling. The nurse must be careful to check on the patient frequently, assist with ambulation, and place the call bell or other needed items within easy reach of the patient.

People with a History of Addiction or Substance/Opioid Use Disorder

People with a history of addiction pose a unique challenge to the implementation of pain management strategies. Patients in recovery are often concerned about the risk of relapse, whether they are addicted to opioids, alcohol, or other substances. And patients who are actively using it may be concerned about withdrawal while being in the hospital, or even whether their pain will be taken seriously, given their history.

Healthcare providers may also struggle with providing opioids for patients with a history of substance abuse: they may be worried about the diversion or overtreatment of pain or be distrustful of a patient’s report of pain (23).

When treating opioid-dependent patients with narcotics for pain, they will likely need higher doses to achieve pain relief. The nurse must carefully monitor patients in this situation due to the risk of toxicity. The addition of adjuvants may also be beneficial in this population.

Patients who refuse opioid treatment due to the risk of relapse should be respected; this may mean finding other viable alternatives, such as non-opioid adjuvants, local or regional medications (like an epidural or spinal block), and non-pharmacological methods of pain relief.

Ask yourself...

- Which pain assessment tool would the nurse use for a newborn infant?

- What measures would the nurse implement for an older adult who is at high risk of falling due to the use of opioid narcotics?

- What tool(s) would the nurse use to assess pain in an elderly adult with dementia?

- Which opioid(s) are contraindicated in patients with a history of substance abuse?

- Can you think of any other patient population who might need special considerations when determining appropriate nursing interventions for acute pain?

Conclusion

Nurses should be knowledgeable about pain management techniques. Left untreated, pain can lead to depression, anxiety, reduced healing, non-compliance with medical treatment, longer hospital stays, poor quality of life, and even reduced patient satisfaction with the healthcare facility. However, treating pain is not simple. It is a complex phenomenon that is experienced differently by everyone and influenced by many different factors.

The nurse plays a vital role in identifying patients with unrelieved pain and advocating for better pain management strategies.

References + Disclaimer

- Akbar, N., Teo, S. P., Artini Hj-Abdul-Rahman, H. N., Hj-Husaini, H. A., & Venkatasalu, M. R. (2019). Barriers and Solutions for Improving Pain Management Practices in Acute Hospital Settings: Perspectives of Healthcare Practitioners for a Pain-Free Hospital Initiative. Annals of geriatric medicine and research, 23(4), 190–196. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.19.0037

- Alorfi N. M. (2023). Pharmacological Methods of Pain Management: Narrative Review of Medication Used. International journal of general medicine, 16, 3247–3256. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S419239

- Boezaart, A. P., Smith, C. R., Chembrovich, S., Zasimovich, Y., Server, A., Morgan, G., Theron, A., Booysen, K., & Reina, M. A. (2021). Visceral versus somatic pain: an educational review of anatomy and clinical implications. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine, 46(7), 629–636. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2020-102084

- Boring, B. L., Walsh, K. T., Nanavaty, N., Ng, B. W., & Mathur, V. A. (2021). How and Why Patient Concerns Influence Pain Reporting: A Qualitative Analysis of Personal Accounts and Perceptions of Others’ Use of Numerical Pain Scales. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 663890. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.663890

- Chen, J.S., Kandle, P.F., Murray, I.V., Fitzgerald, L.A., & Sehdev, J.S. (2023, July 24). Physiology, Pain. In StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539789/

- Chen, Z. S., & Wang, J. (2022). Pain, from perception to action: A computational perspective. iScience, 26(1), 105707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.105707

- Cohen, B., Ruth, L.J., & Preuss, C.V. (Updated 2023, April 29). Opioid Analgesics. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459161/

- Di Maio, G., Villano, I., Ilardi, C. R., Messina, A., Monda, V., Iodice, A. C., Porro, C., Panaro, M. A., Chieffi, S., Messina, G., Monda, M., & La Marra, M. (2023). Mechanisms of Transmission and Processing of Pain: A Narrative Review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 20(4), 3064. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043064

- Dydyk, A.M., & Grandhe, S. (Updated 2023, January 29). Pain Assessment. In StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556098/

- Dufort, A., & Samaan, Z. (2021). Problematic Opioid Use Among Older Adults: Epidemiology, Adverse Outcomes and Treatment Considerations. Drugs & aging, 38(12), 1043–1053. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-021-00893-z

- Dowell, D., Ragan, K., Jones, C.M., Baldwin, G.T., & Chou, R. (2022, November 4). CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opiods for Pain – United States, 2022. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Recommendations and Reports 71(3); 1-95. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/rr/rr7103a1.htm

- Germossa, G. N., Helleso, R., & Sjetne, I. S. (2019). Hospitalized patients’ pain experience before and after the introduction of a nurse-based pain management programme: a separate sample pre and post study. BMC nursing, 18, 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-019-0362-y

- Gerriets, V., Anderson, J., Patel, P., & Nappe, T.M. (Updated 2024, January 11). Acetaminophen. In StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482369/

- Grewal, N., & Huecker, M.R. (Updated 2023, July 21). Opioid Prescribing. In StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551720/

- Khan, A., Khan, S., & Kim, Y. S. (2019). Insight into Pain Modulation: Nociceptors Sensitization and Therapeutic Targets. Current drug targets, 20(7), 775–788. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389450120666190131114244

- Majedi, H., Dehghani, S. S., Soleyman-Jahi, S., Tafakhori, A., Emami, S. A., Mireskandari, M., & Hosseini, S. M. (2019). Assessment of Factors Predicting Inadequate Pain

- Management in Chronic Pain Patients. Anesthesiology and pain medicine, 9(6), e97229. https://doi.org/10.5812/aapm.97229

- MedlinePlus. (2021). Alternative Medicine – Pain Relief. MedlinePlus. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002064.htm

- MedlinePlus. (2023). Non-Drug Pain Management. MedlinePlus. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/nondrugpainmanagement.html

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2023). Pain. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Retrieved from https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/pain

- Nordness, M. F., Hayhurst, C. J., & Pandharipande, P. (2021). Current Perspectives on the Assessment and Management of Pain in the Intensive Care Unit. Journal of pain research, 14, 1733–1744. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S256406

- Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN); Ernstmeyer K, Christman E, editors. Nursing Fundamentals [Internet]. Eau Claire (WI): Chippewa Valley Technical College; 2021. Table 11.3a. [Sample PQRSTU Focused Questions for Pain]. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK591809/table/ch11comfort.T.sample_pqrstu_focused_ques/

- Rababa, M., Al-Sabbah, S., & Hayajneh, A. A. (2021). Nurses’ Perceived Barriers to and Facilitators of Pain Assessment and Management in Critical Care Patients: A Systematic Review. Journal of pain research, 14, 3475–3491. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S332423

- St Marie, B., & Broglio, K. (2020). Managing Pain in the Setting of Opioid Use Disorder. Pain management nursing: official journal of the American Society of Pain Management Nurses, 21(1), 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2019.08.003

- Suen, L. W., McMahan, V. M., Rowe, C., Bhardwaj, S., Knight, K., Kushel, M. B., Santos, G. M., & Coffin, P. (2021). Factors Associated with Pain Treatment Satisfaction Among Patients with Chronic Non-Cancer Pain and Substance Use. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine: JABFM, 34(6), 1082–1095. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2021.06.210214

- Talbot, K., Madden, V. J., Jones, S. L., & Moseley, G. L. (2019). The sensory and affective components of pain: are they differentially modifiable dimensions or inseparable aspects of a unitary experience? A systematic review. British journal of anaesthesia, 123(2), e263–e272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2019.03.033

- Theriot, J., Sabir, S., & Azadfard, M. (Updated 2023, July 21). In StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537079/

- Trachsel, L.A., Munakomi, S., & Cascella, M. (Updated 2023, April 17). Pain Theory. In StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545194/

- Quality and Safety Education for Nurses. (2023. QSEN Institute Competencies. Retrieved from https://www.qsen.org/competencies

- Qureshi, O., & Dua, A. (Updated 2023, March 2). COX Inhibitors. In StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549795/

University of Florida Health. (2024). Pain Assessment Scales/Tools. University of Florida Health. Retrieved from https://pami.emergency.med.jax.ufl.edu/resources/provider-resources/pain-assessment-scales/ - Vaskovic, J. (2023). Neurotransmitters. KenHub. Retrieved from https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/neurotransmitters

- Whitehead, C., & Grider, M.H. (Updated 2023, July 24). Neuroanatomy, Touchg Receptor. In StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547731/

- Yang, S., & Chang, M. C. (2019). Chronic Pain: Structural and Functional Changes in Brain Structures and Associated Negative Affective States. International journal of molecular sciences, 20(13), 3130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20133130

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback!