Course

Rhode Island APRN Bundle

Course Highlights

- In this Rhode Island APRN Bundle we will learn about the most common types of substance abuse, and why it is important for nurses to recognize each type and treat accordingly.

- You’ll also learn to understand the difference between Alzheimer’s and dementia.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of FDA-approved and off-label indications for non-opioid medications and other various therapies for chronic pain management.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 10

Including 7 Pharmacology Hours

Course By:

Various Authors

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Rhode Island Substance Abuse

Introduction

Substance abuse is described as “a pattern of using a substance (drug) that causes significant problems or distress” (1). As of 2020, 37.309 million Americans were currently using illegal drugs (2). Medical professionals are on the front lines of recognizing, treating and providing support to individuals who suffer from substance abuse. This Rhode Island Substance Abuse course will walk you through the different types of substances abused, the prevalence of that abuse, the symptoms one experiences while using that substance, overdose symptoms, and how to counteract an overdose. You will also learn about substance abuse in adolescents, and prevention methods currently being used to combat substance abuse in adolescents.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What do you think are the most abused substances?

- What knowledge do you hope to gain by completing this Rhode Island Substance Abuse course?

Alcohol

Alcohol abuse is the second most common type of substance abuse, with the first being tobacco use (3). While many individuals in the United States can drink alcohol and it is not considered abuse, there are some individuals whose drinking causes harm or distress. In the case of alcohol use disorder, harm or distress is described as alcohol leading to health problems, or trouble while at home, work, school or with law enforcement (3).

There are several signs and symptoms of alcohol use disorder that help one to determine if their loved one needs help. As health care providers, it is important to understand the signs and symptoms to properly help and treat those who are experiencing alcohol use disorder. Symptoms can range from mild to severe, depending on the number of symptoms experienced (5) and include:

- Unable to limit the amount of alcohol consumed

- Wanting to decrease the amount consumed, but being unsuccessful

- Spending a large amount of time obtaining alcohol, drinking alcohol, or recovering from alcohol use

- Having a strong craving or urge to drink alcohol

- Not completing major obligations at work, school or home due to alcohol use

- Continuing to drink alcohol even though you know it is causing problems physically, at work, home, or in relationships

- No participating in social activities or work-related functions to consume alcohol

- Developing a tolerance to alcohol so more is needed to elicit the same effect

- Experiencing symptoms of withdrawal, such as, nauseas, sweating and shaking when you are not drinking

While the above signs and symptoms are typically ones that do not have a medical component attached, alcohol use disorder impacts nearly every organ and system in the body. This widespread impact can have a detrimental effect on an individual suffering from alcohol use disorder (4) such as:

- Neurologic

– Ischemic stroke

– Hemorrhagic stroke - Cardiac

– Cardiomyopathy

– Arrhythmias

– Ischemic heart disease

– Hypertension - Lung

– Acute respiratory distress syndrome

– Pneumonia - Liver

– Steatosis

– Steatohepatitis

– Fibrosis

– Cirrhosis

– Alcohol associated hepatitis

– Liver cancer - Pancreas

– Acute and chronic pancreatitis - Gastrointestinal

– Gut leakiness

– Microbial dysbiosis

– Colorectal cancer

Clear patterns have emerged between alcohol use disorder and increased risk for certain types of cancers (4):

- Head and neck cancer

– Oral cavity

– Pharynx

– Larynx - Esophageal Cancer

- Liver Cancer

- Breast

- Colorectal Cancer

Knowing the effects of chronic alcohol use on the body is important in understanding the treatment methods that will be needed. Treatment options range from spiritual to medical, with many individuals utilizing more than one option (6).

- Detox and withdrawal

– This treatment option is typically done in an inpatient setting. Treatment begins with detoxification, which leads to withdrawal symptoms. These symptoms can be medically managed, and occasionally require sedating medications. Detox and withdrawal generally take 2 to 7 days. - Psychological counseling

– This treatment option will help the individual better understand their problem with alcohol and provide support on the psychological aspects of alcohol use disorder. This type of treatment can be done individually or in a group setting. - Oral medications

– Disulfiram is a medication that helps to curb one’s want for alcohol. While the drug doesn’t remove the urge to drink, it will produce a physical reaction to consuming alcohol in the form of flushing, nausea, vomiting and headaches.

– Naltrexone is used to block the good feelings alcohol causes, which can aid in recovery.

– Acamprosate is used to help curb cravings of alcohol and is generally used in combination with Naltrexone. - Injected medication

– Vivitrol is the injected version of Naltrexone and is injected once a month. Injected medications may be easier, or more consistently used than oral medications. - Medical treatment

– As we’ve learned, alcohol use disorder comes with a large amount of health concerns. These concerns typically require medical treatment in the form of medication, surgery, outpatient care, etc. - Spiritual practice

– It has been shown that individuals involved in some type of spiritual practice find it easier to maintain recovery.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are the five most common types of cancers associated with alcohol use disorder?

- Have you personally taken care of someone with alcohol use disorder? Did they exhibit any symptoms or illnesses listed above?

Marijuana

Marijuana, also known as cannabis, weed or pot, refers to the dried flowers, leaves, stems and seeds of the cannabis plant. In one cannabis plant there are over 100 compounds ranging from tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) to cannabidiol (CBD) (7). While THC and CBD have the same molecular structure, the difference in how the atoms are arranged accounts for the different effects on the body. THC is the main psychoactive compound in cannabis, which produces the high sensation, while CBD, although psychoactive, does not produce the high sensation (8).

Marijuana is the most used federally illegal drug in the United Stated. In 2019, the CDC reported that 48.2 million, or ~18% of Americans have used marijuana at least once. There are several ways to use marijuana, including: smoking in joints, blunts, or bongs, vaping via electronic vaporizing devices, mixing or infusing into foods or drinks, or inhaling oil concentrates (7).

There are many health risks associated with using marijuana, in any form. It is estimated that 3 in 10 people who use marijuana have marijuana use disorder (7).

The risks include:

Brain Health

Since marijuana is a psychoactive drug, the main effect is on brain function. Marijuana specifically affects the parts of the brain responsible for memory, learning, attention, decision making, coordination, emotions and reaction time.

Heart Health

Marijuana is known to make the heart beat faster, which can make blood pressure higher immediately after use. This can lead to an increased risk of stroke, heart disease or vascular disease.

Lung Health

Inhaled marijuana can cause damage to lung tissues and small blood vessels, as well as scarring to the lung. More research is being done to understand the effects of secondhand marijuana smoke.

Mental Health

While the relationship is not fully understood, marijuana has been linked to social anxiety, depression and schizophrenia.

Unintentional Poisoning

There is a greater risk for unintentional poisoning with edibles (marijuana baked or put into food or drinks) than with inhaled marijuana. This risk is because children can easily mistake food with marijuana in it. In some instances, emergency medical care has been required.

As marijuana becomes legal, and readily available across many states, teenagers are gaining better access to it. The CDC reports that 37% of high school students in the United States have reported using marijuana. This use can come with impacts to their developing brains, resulting in (7):

- Difficulty thinking and problem-solving

- Problems with memory and learning

- Reduced coordination

- Difficulty maintaining attention

- Problems with school and social life

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is the difference between THC and CBD?

- What were the 5 health risks listed?

- Were you aware of the health risks associated with marijuana used? Do the health risks surprise you?

Prescription Medicines

Prescription drug abuse is classified as the abuse of a prescription medication that is taken in a way not intended by the prescriber. This abuse can be by the person who the drug was initially prescribed for, or from someone taking another person’s prescription medication. The National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics show that 6% of Americans over the age of 12 abuse prescriptions in a year, and 12% of prescription drug abusers are addicted. This is perpetuated by 4 out of 5 pharmacy filled prescriptions being opioids (10).

Prescription medication is sectioned off into three categories: opioids, anti-anxiety medications/sedatives/hypnotics, and stimulants. Signs and symptoms of prescription drug abuse vary depending on the type of drug used (9). Opioids are a type of medication that is used to treat pain. These medications usually contain oxycodone or hydrocodone. Opioids are the leading cause of drug overdose death, with 74.8% of drug overdose death being from Opioids (11).

The signs of symptoms of opioid drug abuse include (9):

- Constipation

- Nausea

- Feeling high

- Slowed breathing rate

- Drowsiness

- Confusion

- Poor coordination

- Increased dose needed for pain relief

- Worsening or increased sensitivity to pain with higher doses

Anti-anxiety medication, sedatives and hypnotics are used to treat anxiety and sleep disorders. Some medications used for these disorders are alprazolam (Xanax), diazepam (Valium), and zolpidem (Ambien).

The signs and symptoms of drug abuse by these types of medications are (9):

- Drowsiness

- Confusion

- Unsteady walking

- Slurred speech

- Poor concentration

- Dizziness

- Problems with memory

- Slowed breathing

Stimulants are a type of medication used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and certain sleep disorders. Some medications used to treat these disorders include methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta, and others), dextroamphetamine-amphetamine (Adderall XR, Mydayis) and dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine).

Signs and symptoms of drug abuse by these types of medications are (9):

- Increased alertness

- Feeling high

- Irregular heartbeat

- High blood pressure

- High body temperature

- Reduced appetite

- Insomnia

- Agitation

- Anxiety

- Paranoia

Medical complications differ depending on the type of medication abused. Opioids can decrease respiratory rate with the potential for breathing to stop altogether. They can also cause a coma, and lead to death. Anti-anxiety/sedatives/hypnotics can cause memory problems, low blood pressure and slowed breathing. Like opioids, they can also lead to coma or death. Abrupt withdrawal of these medications can lead to an overactive nervous system and seizures. Stimulants can increase the bodies temperature, produce heart problems, high blood pressure, seizures or tremors, hallucinations, aggressiveness, and paranoia (9).

Opioids can be reversed with a medication called Naloxone. This medication works by binding to the opioid receptors, then reversing and blocking the effects of other opioids. It is used to restore an individual’s breathing and can be given through injection or nasal spray. If Naloxone is given outside of a medical facility, emergency personnel should be contacted immediately (18).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Were you surprised to learn that most prescriptions filled in pharmacies are opioids?

- Think about the number of children who are on ADHD medication. Do you think they or their guardians should receive in-depth training and education on the potential dangers of that medication?

- What symptoms were similar? What symptoms were different?

Methamphetamine

Methamphetamine is a highly addictive, man-made, central nervous system stimulant. This drug increases heart rate, body temperature, respiration, and blood pressure. It also enhances one’s energy, attention, focus, pleasure, and excitement (12). It has commonly been referred to as meth, ice, speed, and crystal. Research has shown that 2.5 million Americans aged 12 or older reported using methamphetamine within the past year. 53% of those individuals met diagnostic criteria for methamphetamine use disorder, but less than 1 in 3 received substance use treatment within the past year (13).

There are four ways methamphetamine can be used: smoking, swallowing (pill), snorting, or injecting the powder that has been dissolved in water or alcohol. While methamphetamine produces a high quickly, it also fades quickly. This produces what is called and “binge and crash” pattern of use. This type of use is where an individual will take the drug every few hours for several days at a time, resulting in lack of food and sleep (14).

There is a substantial amount of long-term health effects from methamphetamine use. Those who inject methamphetamine are at a higher risk for contracting infectious diseases like HIV and hepatitis C.

Other long-term problems include (14):

- Extreme weight loss

- Severe dental problems

- Intense itching which can lead to skin sores and infection from scratching

- Anxiety

- Changes in brain structure and function

– Changes have been noted to the brain’s dopamine system which has resulted in problems with coordination and verbal learning.

– Severe changes have also been noted to the areas of the brain that deal with emotion and memory - Confusion and memory loss

- Sleeping problems

- Violent behavior

- Paranoia

- Hallucinations

Due to the effect methamphetamine has on the body, an overdose often leads to a stroke, heart attack, or organ problems. Because of this, it is imperative health care providers restore blood flow to the affected part of the brain for a stroke, restore blood flow to the heart in the event of a heart attack, or treat the organ issues that present (14). Treatment for methamphetamine use disorder focuses on cognitive-behavioral therapy and motivational incentives, such as vouchers or small cash rewards that encourage individuals to remain drug-free. There is currently no FDA approved medication to treat a methamphetamine addiction (14).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

-

What are the 10 long-term effects methamphetamine can have on the body as noted in this Rhode Island Substance Abuse course?

-

Have you seen any of these long-term effects in your nursing practice?

-

Does it surprise you that there is no medication to treat a methamphetamine overdose?

Cocaine

Cocaine is a highly addictive stimulant drug that is derived from the leaves of the coco plant that is native to South America. Dealers of cocaine may add in other drugs to the cocaine, such as amphetamine or synthetic opioids, like fentanyl. Adding in synthetic opioids can be especially dangerous and lead to overdose and even death (15). Over 5 million Americans reported current cocaine use in 2020, with nearly 1 in 5 overdose deaths reported (13).

There are several ways in which cocaine can be used: in powder form it can be snorted or rubbed into an individual’s gums, the powder can be dissolved and injected into the bloodstream, or if the cocaine is in crystal form, it can be heated and smoked. Injecting cocaine produces a faster and more intense high but is short-lasting. Cocaine affects the brain by increasing the amount of dopamine produced. This increase of dopamine floods the brain’s reward circuit, which reinforces drug-taking behavior. Repeated cocaine use can lead to the brain’s reward circuit becoming less sensitive, which leads to individuals taking stronger and more frequent doses to achieve the same high as before (15).

The effects of cocaine are felt almost immediately and can disappear within a few minutes to an hour. There are several health effects from using cocaine (15):

- Extreme happiness and energy

- Mental alertness

- Hypersensitivity to sight, sound, and touch

- Irritability

- Paranoia

- Constricted blood vessels

- Dilated pupils

- Nausea

- Increase in body temperature and blood pressure

- Increased or irregular heartbeat

- Tremors/muscle twitches

- Restlessness

There are several long-term effects of cocaine use. These effects can range from common, to being dependent on the method of use (15)

- Malnourished due to a decreased appetite

- Movement disorders

- Irritability

- Restlessness

- Auditory hallucinations

- Snorting cocaine

– Loss of smell

– Nosebleeds

– Frequent runny nose

– Problems with swallowing - Smoking cocaine

– Cough

– Asthma

– Respiratory distress

– Higher risk for infections like pneumonia - Consuming cocaine by mouth

– Severe bowel decay due to reduced blood flow - Injecting cocaine

– Increased risk of contracting HIV, hepatitis B and C, and other blood-borne diseases

– Skin or soft tissue infections

– Scarring or collapsed veins

A cocaine overdose is similar to that of a methamphetamine overdose, with the inclusion of seizures. Like methamphetamine, it is critical that health care providers restore blood flow to the heart and brain in the event of a heart attack or stroke. If an individual presents with a seizure due to a cocaine overdose, the first action to be taken is to stop the seizure. Cocaine mirrors that of methamphetamine use in terms of increased dopamine in the brain. This leads to an addictive nature, as well as needing more drug overtime to produce the same high (15).

Unfortunately, there is no FDA medication approved to treat cocaine use disorder.

There are several behavioral therapy options available (15):

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy

- Contingency management or motivational incentives

- Therapeutic communities

– These are residences in which people can recover from substance use disorders with other individuals who understand their addiction, all while being drug-free - Community based recovery groups

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How many Americans stated they had used cocaine in 2020? Did that number surprise you? Did you think it would be higher or lower?

- While a cocaine overdose may be similar to that of a methamphetamine overdose, what additional overdose symptom can happen with cocaine use?

- There are four methods in which cocaine can be used, what long-term side effects stem from those four methods?

Heroin

Heroin is a type of drug made from morphine, which is derived from the seed pod of opium poppy plants (16). According to the CDC, over 19% of all opioid overdose deaths in 2020 involved the use of heroin (17). Heroin can be found as a white or brown powder, or a black tar like substance. Like cocaine and methamphetamine, heroin can be injected into the bloodstream, snorted, or heated and smoked. Additionally, some individuals mix heroin with cocaine, or alcohol. This created an even higher risk for an overdose, and potentially death (16).

The effects of heroin on the body are like those of prescribed opioids. When heroin reaches the brain, it is turned into morphine, which binds to opioid receptors. This causes the user to feel what is described as a rush, or a pleasurable sensation. How intense the rush is, is determined by how much drug has been taken and how quickly it attaches itself to the opioid receptor (16).

Along with the rush, there are several short-term effects that people may experience when using heroin (16):

- Dry mouth

- Warm, flushing of the skin

- Heaving feeling in their arms and legs

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Severe itching

- Clouded mental functioning

- Being in a back-and-forth state of consciousness and semi-consciousness

Individuals with heroin use disorder may experience some of the following long term health effects (16):

- Insomnia

- Collapsed or damaged veins from injecting the drug

- Damaged tissues on the inside of the nose due to snorting the drug

- Infection in the lining of the heart and the valves

- Abscesses

- Constipation and stomach cramping

- Liver and kidney disease

- Lung complications, like pneumonia

- Mental disorders like depression and antisocial personality disorder

- Sexual dysfunction in men

- Irregular menstrual cycle in women

- Increased risk for blood borne diseases such as HIV and hepatitis C

Heroin overdoses, along with opioid overdoses, have been increasing in the United States. A heroin overdose depresses one’s heart rate as well as breathing, leading to hypoxia. However, Naloxone is a medication that can reverse opioid overdoses, if given the correct way. Naloxone can be injected or snorted and has recently been approved for over the counter dispense in several states (18).

Those who suffer from heroin use disorder have a wider variety of treatments at their disposal. Behavioral therapies include cognitive-behavioral therapy as well asl contingency management. It has been shown that these behavioral therapies work best when used in-conjunction with medications.

There are three different types of medications available to those with heroin use disorder (16):

Methadone

This is an opioid receptor full agonist, which means it attaches itself to and actives an opioid receptor to help ease withdrawal symptoms of heroin cravings

Buprenorphine

This is an opioid receptor partial agonist, which means it attaches itself to and partially activates opioid receptors to help ease withdrawal symptoms and heroin cravings

Naltrexone

This is an opioid receptor antagonist, which means it prevents heroin from binding to opioid receptors, blocking the effects

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What plant is heroin derived from? Were you aware of this before this course Rhode Island Substance Abuse course?

- Have you been educated on the proper way to administer Narcan to an individual suffering from a heroin or opioid overdose? Do you feel like this is something all health care professionals should be educated on?

- What are the three medications approved for treatment of heroin use disorder?

Hallucinogens

Hallucinogenic drugs are described as a group of drugs that alter a person’s awareness of their surroundings, thoughts, and feelings (19). In 2019 it was estimated that 5.5 million people in the United States used hallucinogens within that past year (20). Hallucinogenic drugs are split into two categories: classic hallucinogens and dissociative drugs. Like the name suggests, both types of hallucinogens can cause the user to experience hallucinations, but dissociative drugs can also cause the user to feel out of control or disconnected from their body (19).

Common classic hallucinogens include (19):

D-lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD)

Considered one of the most powerful mind-altering chemicals. This drug is a clear or white odorless material, made from lysergic acid. Lysergic acid is found on fungus that will grow on rye and other grains.

4-phosphoryloxy-N, N-dimethyltryptamine (Psilocybin)

This hallucinogenic is also referred to “magic mushrooms” or “shrooms” since it is found on certain types of mushrooms in South America, Mexico, and the United States.

Mescaline (Peyote)

Peyote comes from a small, spineless cactus, but may also be synthetic. While it is illegal in the United States, it can be used in religious ceremonies in the Native American Church.

N, N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT)

A chemical found in some Amazonian plants. It can be made into a tea called Ayahuasca or smoked if synthetically made.

251-NBOMe

This is a synthetic hallucinogen that is like LSD and MDMA but is more potent. It was originally developed for use in brain research. It has also been referred to as “N Bomb” or “251”.

Common dissociative drugs include (19):

Phencyclidine (PCP)

This drug was initially developed for surgery in the 1950’s, but due to its serious side effects it is no longer used. It can be found in several forms, such as: tablets, liquid, and white crystal powder.

Ketamine

This drug is used as an anesthetic for both humans and animals and is typically stolen or sold illegally from veterinary offices. Ketamine comes in powder, pills, or liquid form.

DXM (Dextromethorphan)

This drug is used as a cough suppressant and muscus-clearing ingredient in over-the-counter cold and cough medicines. It can be found in syrup, tablet or gel capsule form.

Saliva divinorum (Salvia)

This is a plant that is common to southern Mexico and Central and South America. It’s leaves or typically chewed, or the juice that is extracted from them is drank. Saliva can also be inhaled.

The short- and long-term side effects of hallucinogens are different depending on the type and category of hallucinogenic used. Short-term side effects for classic hallucinogens are (19):

- Hallucinations

- Increased heart rate

- Nausea

- Intensified feelings and sensory experiences

- Changes in sense of time

- Increased blood pressure, breathing and body temperature

- Loss of appetite

- Dry mouth

- Sleep problems

- Uncoordinated movements

- Excessive sweating

- Panic

- Paranoia

- Psychosis

There are two specific long-term side effects of classic hallucinogens. These side effects are typically seen in individuals with a history of mental illness but can happen to anyone (19).

Persistent Psychosis

- This refers to a series of continuing mental problems that include:

- Visual disturbances

- Disorganized thinking

- Paranoia

- Mood changes

Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD)

This is a recurrence of certain drug experiencs like hallucinations or visual disturbances. These typically happen without warning and can occur any time after drug use.

Antidepressants and antipsychotic medicals have been used to improve an individual’s mood, as well as treat psychosis. Behavioral therapies have been used to help individuals cope with fear or confusion associated with visual disturbances.

Short-term side effects for dissociative drugs have been known to appear within a few minutes of taking the drug and can last hours or days. If the dosage is low, dissociative drugs can cause the following effects (19):

- Numbness

- Disorientation and loss of coordination

- Hallucinations

- Increase in the user’s blood pressure, heart rate and body temperature

If higher doses of dissociative drugs are taken the following side effects may occur (19):

- Memory loss

- Panic and anxiety attacks

- Seizures

- Psychotic symptoms

- Amnesia

- Inability to move

- Mood swings

- Trouble breathing

The long-term side effects of dissociative drugs are still being researched. However, repeated and prolonged use of PCP has been known to result in addiction. The following long-term effects may continue for a year or more after the drug use stops (19):

- Speech problems

- Memory Loss

- Weight Loss

- Anxiety

- Depression and suicidal thoughts

Most classic hallucinogen use will not result in an overdose but tend to have extremely unpleasant experiences when taken in higher doses. There have been some serious medical emergencies and fatalities that have been reported by 251-NBOMe. Overdose becomes more likely with dissociative drugs. High doses of PCP have been known to cause seizures, coma, and death (19).

Due to the nature of hallucinogens, there is a high risk of bodily harm due to the alteration of the user’s perception and mood (19):

- Users could attempt things they wouldn’t normally do when not under the influence, such as jumping out of a window or off a building.

- Users could experience a profound sadness or feeling of hopelessness leading to suicidal feelings and/or suicidal actions.

- Psilocybin users could accidently consume a poisonous mushroom that look like psilocybin, which can result in severe illness or death.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

-

What are the two categories of hallucinogens?

-

How many hallucinogens are derived from plants? What plants are they?

Substance Abuse in Adolescents

Substance abuse and opioid overdose deaths are beginning to affect school systems. In 2017, 2.2 million adolescents between the ages of 12-17 stated they were currently using illicit substances (21).

Brain growth and development, particularly during one’s adolescent years, has been highly studied and reviewed. One area of the brain that is still developing during adolescents is the prefrontal cortex. This area of the brain is responsible for allowing one to assess situations, make decisions, and keep emotions and desires under control (21). Because this area of the brain is still developing, it places adolescents at an increased risk of trying drugs and continuing them (21).

Substance use during one’s adolescent years has the potential to create several long-term negative effects. It is estimated that 90% of individuals with addictions began using substances during their adolescent years (22). There are several factors that can lead to substance use. These risk factors include family history of addiction, mental health concerns, behavioral or impulse control problems, exposure to trauma, and environmental factors (22).

Multiple studies have shown that the science of prevention may affect the probability of later problems (23). The main goal in adolescent substance abuse prevention is to reduce risk factors and overall enhance/reinforce protective factors (23). Depending on the addiction, medication may be used in combination with a form of behavioral therapy or counseling.

There are several types of behavioral therapies:

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Helps individuals recognize, avoid and cope with situations in which they may use drugs.

Contingency Management

Uses positive reinforcement for attending counseling sessions, remaining drug-free, or taking prescribed medications.

Motivational Enhancement Therapy

Focuses on strategies that make the most of an individual’s readiness to change their current behavior and enter treatment.

Family Therapy

Focuses on utilizing the family to address influences on drug patterns and improve overall family function.

Twelve-Step Facilitation

Delivered in 12-week sessions. There are no medical treatments, but allow the individual to social and complementary support.

Follows 12 steps of acceptance, surrender, and active involvement in recovery

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How many adolescents stated they had tried illicit substances in 2017?

- What is the estimated percentage of individuals with addictions who began using substances in their adolescent years?

- There are five different forms of behavior therapy listed in this Rhode Island Substance Abuse course, what are they?

Conclusion

Substance abuse in the United States is on the rise, with many hospitals and health care centers seeing an increase in patients. Understanding the different types of substances used, their short- and long-term symptoms, overdose symptoms, and medication options will help prepare you to care for these individuals. It is equally important to understand the behavioral therapy options for those with substance use disorders, and advocate for them while they are in your care.

Alzheimers Nursing Care

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease is a destructive, progressive, and irreversible brain disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking. Alzheimer’s is the most common cause of dementia in older adults (1). For most people who have Alzheimer’s disease, symptoms first appear in their mid 60’s (1).

Studies suggest more than 5.5 million Americans, most 65 or older, may have dementia caused by Alzheimer’s (1). It is currently listed as the sixth leading cause of death in the United States. It is essential to understand the signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s dementia and how to manage the care of a patient, family member, or friend suffering from the disease.

Dementia is the loss of cognitive functioning, such as thinking, remembering, reasoning, and behavioral abilities, such as a decreased ability to perform activities of daily living (1). The severity of dementia ranges from mild to severe. Dmentia’s mildest stage often begins with forgetfulness, while its most severe stage consists of complete dependence on others for general activities of daily living (1).

History of Alzheimer’s

Alzheimer’s disease is named after Dr. Alois Alzheimer. In the early 1900s, Dr. Alzheimer noticed changes in the brain tissue of a patient who had died of an unknown mental illness. The patient’s symptoms included memory loss, language problems, and unpredictable behavior.

After her death, her brain was examined and was noted to have abnormal clumps known as amyloid plaques and tangled bundled fibers, known as neurofibrillary or tau tangles (1). These plaques and tangles within the brain are considered some of the main features of Alzheimer’s disease. Another feature includes connections of neurons in the brain. Neurons are a type of nerve cell responsible for sending messages between different parts of the brain and from the brain to other parts of the body (1).

Scientists are continuing to study the complex brain changes involved with the disease of Alzheimer’s. The changes in the brain could begin ten years or more before cognitive problems start to surface.

During this stage of the disease, people affected seem to be symptom-free; however, toxin changes occur within the brain (1). Initial damage in the brain occurs within the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, which are the parts of the brain that are necessary for memory formation. As the disease progresses, additional aspects of the brain become affected, and overall brain tissue shrinks significantly (1).

Signs and Symptoms & Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease

Memory problems are typically among the first signs of cognitive impairment related to Alzheimer’s disease. Some people with memory problems have Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) (2). In this condition, people have more memory problems than usual for their age; however, their symptoms do not interfere with their daily lives.

Older people with MCI are at increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. The first symptoms of Alzheimer’s may vary from person to person. Many people display a decline in non-memory-related aspects of cognition, such as word-finding, visual issues, impaired judgment, or reasoning (2).

Healthcare providers use several methods and tools to determine the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Dementia. Diagnosis and evaluation involve memory, problem-solving, attention, counting, and language tests. Healthcare providers may perform brain scans, including CVT. MRI or PET is used to rule out other causes of symptoms.

Various tests may be repeated to give doctors information about how memory and cognitive functions change over time. They can help diagnose different causes of memory problems, such as stroke, tumors, Parkinson’s disease, and vascular dementia. Alzheimer’s disease can be diagnosed only after death by linking clinical measures with an examination of brain tissue in an autopsy (3).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Have you experienced a patient in your practice with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease? What did their symptoms look like?

- What standard diagnostic tools do healthcare providers use to diagnose this disease?

- What is the definitive diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease?

Stages of Disease

Mild Alzheimer’s

People experience significant memory loss and other cognitive problems as the disease progresses. Most people are diagnosed in this stage (1).

- Wandering/getting lost

- Trouble handling money or paying bills

- Repeating questions

- Taking longer to complete basic daily tasks

- Personality/behavioral changes (1)

Moderate Alzheimer’s

In this stage, damage occurs in the area of the brain that controls language, reasoning, sensory processing, and conscious thought (1).

- Memory and confusion worsen.

- Problems recognizing family and friends

- Unable to learn new things

- Trouble with multi-step tasks such as getting dressed

- Trouble coping with situations

- Hallucinations/delusions/paranoia (1)

Severe Alzheimer’s

- Plaques and tangles spread throughout the brain, and brain tissue shrinks significantly.

- Cannot communicate

- Entirely dependent on others for care

- Bedridden – most often as the body shuts down

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some of the signs and symptoms that differentiate each stage of Alzheimer’s disease?

- A person is in what stage of Alzheimer’s disease when they struggle to recognize family members and friends?

Prevention

Many aging patients worry about developing Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Especially if they have had a family member who suffered from the disease, patients may worry about genetic risk. Although there have been many ongoing studies on the prevention of the disease, nothing has been proven to prevent or delay dementia caused by Alzheimer’s disease (2).

More research suggests that women are more likely to develop dementia and Alzheimer’s compared to men. Further research is needed to determine the role between genetics, sex, and Alzheimer’s risk (4).

A review led by experts from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine found encouraging yet inconclusive evidence for three types of interventions related to ways to prevent or delay Alzheimer’s Dementia or age-related cognitive decline (2):

- Increased physical activity

- Blood pressure control

- Cognitive training

Treatment of the Disease

Alzheimer’s disease is complex and is continuously being studied. Current treatment approaches focus on helping people maintain their mental function, manage behavioral symptoms, and lower the severity of symptoms. The FDA has approved several prescription drugs to treat those diagnosed with Alzheimer’s (3).

Treating symptoms of Alzheimer’s can provide patients with comfort, dignity, and independence for a more significant amount of time while simultaneously assisting their caregivers. The approved medications are most beneficial in the early or middle stages of the disease (3).

Cholinesterase inhibitors are prescribed for mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease; they may help to reduce symptoms. Medications include Rzadyne®, Exelon®, and Aricept® (3). Scientists do not fully understand how cholinesterase inhibitors work to treat the disease; however, research indicates that they prevent acetylcholine breakdown. Acetylcholine is a brain chemical believed to help memory and thinking (3).

For those suffering from moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease, a medication known as Namenda®, which is an N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist, can be prescribed. This drug helps to decrease symptoms, allowing some people to maintain certain essential daily functions slightly longer than they would without medication (3).

For example, this medication could help a person in the later stage of the disease maintain their ability to use the bathroom independently for several more months, benefiting the patient and the caregiver (3). This drug works by regulating glutamate, an essential chemical in the brain. When it is produced in large amounts, glutamate may lead to brain cell death. Because NMDA antagonists work differently from cholinesterase inhibitors, these rugs can be prescribed in combination (3).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Is there a cure for this disease?

- What are some of the treatment forms that have been used for the management of Alzheimer’s disease?

- Can medications be used in conjunction with one another to treat the disease?

Medications to be Used with Caution in those Diagnosed with Alzheimer’s

Some medications, such as sleep aids, anxiety medications, anticonvulsants, and antipsychotics, should only be taken by a patient diagnosed with Alzheimer’s after the prescriber has explained the risks and side effects of the medications (3).

Sleep aids: They help people get to sleep and stay asleep. People with Alzheimer’s should not take these drugs regularly because they could make the person more confused and at a higher risk for falls.

Anti-anxiety: These treat agitation and can cause sleepiness, dizziness, falls, and confusion (3).

Anticonvulsants: These are used to treat severe aggression and have possible side effects of mood changes, confusion, drowsiness, and loss of balance.

Antipsychotics: they are used to treat paranoia, hallucinations, agitation, and aggression. Side effects can include the risk of death in older people with dementia. They would only be given when the provider agrees the symptoms are severe enough to justify the risk (3).

Caregiving

Coping with Agitation and Aggression

People with Alzheimer’s disease may become agitated or aggressive as the disease progresses. Agitation causes restlessness and causes someone to be unable to settle down. It may also cause pacing, sleeplessness, or aggression (5). As a caregiver, it is essential to remember that agitation and aggression are usually happening for reasons such as pain, depression, stress, lack of sleep, constipation, soiled underwear, a sudden change in routine, loneliness, and the interaction of medications (5). Look for the signs of aggression and agitation. It is helpful to prevent problems before they happen.

Ways to cope with agitation and aggression (5):

- Reassure the person. Speak calmly. Listen to concerns and frustrations.

- Allow the person to keep as much control as possible.

- Build in quiet times along with activities.

- Keep a routine.

- Try gently touching, soothing music, reading, or walks.

- Reduce noise and clutter.

- Distract with snacks, objects, or activities.

Common Medical Problems

In addition to the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, a person with Alzheimer’s may have other medical conditions over time. These additional health conditions can cause confusion and behavior changes. The person may be unable to communicate with you about their circumstances. As a caregiver, it is essential to watch for various signs of illness and know when to seek medical attention for the person being cared for (6).

Fever

Fever could indicate potential infection, dehydration, heatstroke, or constipation (6).

Flu and Pneumonia

These are easily transmissible. Patients 65 years or older should get the flu and Pneumonia shot each year. Flu and Pneumonia may cause fever, chills, aches, vomiting, coughing, or trouble breathing (6).

Falls

As the disease progresses, the person may have trouble with balance and ambulation. They may also have changes in depth perception. To reduce the chance of falls, clean up clutter, remove throw rugs, use armchairs, and use good lighting inside (6).

Dehydration

It is important to remember to ensure the person gets enough fluid. Signs of dehydration include dry mouth, dizziness, hallucinations, and rapid heart rate (6).

Wandering

Many people with Alzheimer’s disease wander away from their homes or caregivers. As the caregiver, it is essential to know how to limit wandering and prevent the person from becoming lost (7).

Steps to follow before a person wanders (7)

- Ensure the person carries an ID or wears a medical bracelet.

- Consider enrolling the person in the Medic Alert® + Alzheimer’s Association Safe Return Program®.

- Alert neighbors and local police that the person tends to wander and ask them to alert you immediately if they are seen alone.

- Place labels on garments to aid in identification.

Tips to Prevent Wandering (7)

- Keep doors locked. Consider a key or deadbolt.

- Use loosely fitting doorknob covers or safety devices.

- Place STOP, DO NOT ENTER< or CLOSED signs on doors.

- Divert the attention of the person away from using the door.

- Install a door chime that will alert when the door is opened.

- Keep shoes, keys, suitcases, coats, and hats out of sight.

- Make sure not to leave a person who has a history of wandering unattended.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are the basic implementations you can make as a caregiver to make handling confusion and aggression easier in a patient with Alzheimer’s?

- What are some of the types of medical problems that people with Alzheimer’s may face, and how can they be monitored for prevention?

Conclusion

Alzheimer’s is a sad, debilitating, progressive disease that robs patients of their lives and dignity. As research continues on the causes, treatment, and prevention of the disease, healthcare workers and caregivers need to know the signs and symptoms of a patient with Alzheimer’s disease and potential coping mechanisms and management strategies of the disease. More information on the disease is available through several various resources, including:

Family Caregiver Alliance

800-445-8106

NIA Alzheimer’s and Related Dementias Education and Referral Center

800-438-4380

Controlled Substances

Introduction

Pain is complex and subjective. The experience of pain can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life. According to the National Institute of Health (NIH) (40), pain is the most common complaint in a primary care office, with 20% of all patients reporting pain. Chronic pain is the leading cause of disability, and effective pain management is crucial to health and well-being, particularly when it improves functional ability. Effective pain treatment starts with a comprehensive, empathic assessment and a desire to listen and understand. Nurse Practitioners are well-positioned to fill a vital role in providing comprehensive and empathic patient care, including pain management (23).

While the incidence of chronic pain has remained a significant problem, how clinicians manage pain has significantly changed in the last decade, primarily due to the opioid epidemic. This education aims to discuss pain and the assessment of pain, federal guidelines for prescribing, the opioid epidemic, addiction and diversion, and recommendations for managing pain.

Definition of Pain

Understanding the definition of pain, differentiating between various types of pain, and recognizing the descriptors patients use to communicate their pain experiences are essential for Nurse practitioners involved in pain management. By understanding the medical definition of pain and how individuals may communicate it, nurse practitioners can differentiate varying types of pain to target assessment.

According to the International Association for the Study of Pain (27), pain is “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or terms of described such in damage.” The IASP, in July 2020, expanded its definition of pain to include context further.

Their expansion is summarized below:

- Pain is a personal experience influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors.

- Pain cannot be inferred solely from activity in sensory neurons.

- Individuals learn the concept of pain through their life experiences.

- A person’s report of an experience in pain should be respected.

- Pain usually serves an adaptive role but may adversely affect function and social and psychological well-being.

- The inability to communicate does not negate the possibility of the experience of pain.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Analyze how changes to the definition of pain may affect your practice.

- Discuss how you manage appointment times, knowing that 20% of your scheduled patients may seek pain treatment.

- How does the approach to pain management change in the presence of a person with a disability?

Types of Pain

Pain originates from different mechanisms, causes, and areas of the body. As a nurse practitioner, understanding the type of pain a patient is experiencing is essential for several reasons (23).

- Determining an accurate diagnosis. This kind of pain can provide valuable clues to the underlying cause or condition.

- Creating a treatment plan. Different types of pain respond better to specific treatments or interventions.

- Developing patient education. A nurse practitioner can provide targeted education to patients about their condition, why they may experience the pain as they do, its causes, and treatment options. Improving the patient's knowledge and control over their condition improves outcomes.

Acute Pain

Acute pain is typically short-lived and is a protective response to an injury or illness. Patients are usually able to identify the cause. This type of pain resolves as the underlying condition improves or heals (12).

Chronic Pain

Chronic pain is diagnosed when it continues beyond the expected healing time. Pain is defined as chronic when it persists for longer than three months. It may result from an underlying disease or injury or develop without a clear cause. Chronic pain often significantly impacts a person's physical and emotional well-being, requiring long-term management strategies. The prolonged experience of chronic pain usually indicates a central nervous system component of pain that may require additional treatment. Patients with centralized pain often experience allodynia or hyperalgesia (12).

Allodynia is pain evoked by a stimulus that usually does not cause pain, such as a light touch. Hyperalgesia is the effect of a heightened pain response to a stimulus that usually evokes pain (12).

Nociceptive Pain

Nociceptive pain arises from activating peripheral nociceptors, specialized nerve endings that respond to noxious stimuli. This type of pain is typically associated with tissue damage or inflammation and is further classified into somatic and visceral pain subtypes.

Somatic pain is most common and occurs in muscles, skin, or bones; patients may describe it as sharp, aching, stiffness, or throbbing.

Visceral pain occurs in the internal organs, such as indigestion or bowel spasms. It is more vague than somatic pain; patients may describe it as deep, gnawing, twisting, or dull (12).

Neuropathic pain

Neuropathic pain is a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system. Examples include trigeminal neuralgia, painful polyneuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, and central poststroke pain (10).

Neuropathic pain may be ongoing, intermittent, or spontaneous pain. Patients often describe neuropathic pain as burning, prickling, or squeezing quality. Neuropathic pain is a common chronic pain. Patients commonly describe allodynia and hyperalgesia as part of their chronic pain experience (10).

Affective pain

Affective descriptors reflect the emotional aspects of pain and include terms like distressing, unbearable, depressing, or frightening. These descriptors provide insights into the emotional impact of pain on an individual's well-being (12).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How can nurse practitioners effectively elicit patient descriptors to accurately assess the type of pain the patient is experiencing?

- Expand on how pain descriptors can guide interventions even if the cause is not yet determined.

- What strategies ensure patients feel comfortable describing their pain, particularly regarding subjective elements such as quality and location?

Case Study

Mary Adams is a licensed practical nurse who has just relocated to town. Mary will be the utilization review nurse at a local long-term care facility. Mary was diagnosed with Postherpetic Neuralgia last year, and she is happy that her new job will have her mostly doing desk work and not providing direct patient care as she had been before the relocation. Mary was having difficulty at work at her previous employer due to pain. She called into work several times, and before leaving, Mary's supervisor had counseled her because of her absences.

Mary wants to establish primary care immediately because she needs ongoing pain treatment. She is hopeful that, with her new job and pain under control, she will be able to continue a successful career in nursing. When Mary called the primary care office, she specifically requested a nurse practitioner as her primary care provider because she believes that nurse practitioners tend to spend more time with their patients.

Assessment

The assessment effectively determines the type of treatment needed, the options for treatment, and whether the patient may be at risk for opioid dependence. Since we know that chronic pain can lead to disability and pain has a high potential to negatively affect the patient's ability to work or otherwise, be productive, perform self-care, and potentially impact family or caregivers, it is imperative to approach the assessment with curiosity and empathy. This approach will ensure a thorough review of pain and research on pain management options. Compassion and support alone can improve patient outcomes related to pain management (23).

Record Review

Regardless of familiarity with the patient, reviewing the patient's treatment records is essential, as the ability to recall details is unreliable. Reviewing the records can help identify subtle changes in pain description and site, the patient's story around pain, failed modalities, side effects, and the need for education, all impacting further treatment (23).

Research beforehand the patient's current prescription and whether or not the patient has achieved the maximum dosage of the medication. Analysis of the patient's past prescription could reveal a documented failed therapy even though the patient did not receive the maximum dose (23).

A review of documented allergens may indicate an allergy to pain medication. Discuss with the patient the specific response to the drug to determine if it is a true allergy, such as hives or anaphylaxis, or if the response may have been a side effect, such as nausea and vomiting.

Research whether the patient tried any non-medication modalities for pain, such as physical therapy (PT), occupational therapy (OT), or Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). Note any non-medication modalities documented as failed therapies. The presence of any failed therapies should prompt further discussion with the patient, family, or caregiver about the experience. The incompletion of therapy should not be considered failed therapy. Explore further if the patient abandoned appointments.

Case Study

You review the schedule for the week, and there are three new patient appointments. One is Mary Adams. The interdisciplinary team requested and received Mary's treatment records from her previous primary care provider. You make 15 minutes available to review Mary's records and the questionnaire Mary filled out for her upcoming appointment. You see that Mary has been diagnosed with Postherpetic Neuralgia and note her current treatment regimen, which she stated was ineffective. You write down questions you will want to ask Mary. You do not see evidence of non-medication modalities or allergies to pain medication.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What potential risks or complications can arise from neglecting to conduct a thorough chart review before initiating a pain management assessment?

- In your experience, what evidence supports reviewing known patient records?

- What is an alternative to reviewing past treatment if records are not available?

Pain Assessment

To physically assess pain, several acronyms help explore all the aspects of the patient's experience. Acronyms commonly used to assess pain are SOCRATES, OLDCARTS, and COLDERAS. These pain assessment acronyms are also helpful in determining treatment since they include a character and duration of pain assessment (23).

| O-Onset | S-Site | C-Character |

| L-Location | O-Onset | O-Onset |

| D-Duration | C-Character | L-Location |

| C-Character | R-Radiate | D-Duration |

| A-Alleviating | A-Associated symptoms | E-Exacerbating symptoms |

| R-Radiating, relieving | T-Time/Duration | R-Relieving, radiating |

| T-Temporal patterns (frequency) | E-Exacerbating | A-Associated symptoms |

| S-Symptoms | S-Severity | S-Severity of illness |

Inquire where the patient is feeling pain. The patient may have multiple areas and types of pain. Each type and location must be explored and assessed. Unless the pain is from a localized injury, a body diagram map, as seen below, is helpful to document, inform, and communicate locations and types of pain. In cases of Fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, or other centralized or widespread pain, it is vital to inquire about radiating pain. The patient with chronic pain could be experiencing acute pain or a new pain site, such as osteoarthritis, that may need further evaluation and treatment (23).

Inquire with the patient how long their pain has been present and any associated or known causative factors. Pain experienced longer than three months defines chronic versus acute pain. Chronic pain means that the pain is centralized or a function of the Central Nervous system, which should guide treatment decisions.

To help guide treatment, ask the patient to describe their pain. The description helps identify what type of pain the patient is experiencing: Allodynia and hyperalgesia indicate centralized pain; sharp, shooting pain could indicate neuropathic pain. Have the patient rate their pain. There are various tools, as shown below, for pain rating depending on the patient's ability to communicate. Not using the pain rating number alone is imperative. Ask the patient to compare the severity of pain to a previous experience. For example, a 1/10 may be experienced as a bumped knee or bruise, whereas a 10/10 is experienced on the level of a kidney stone or childbirth (23).

Besides the 0-10 rating scale and depending on the patient's needs, several pain rating scales are appropriate. They are listed below.

The 0-5 and Faces scales may be used for all adult patients and are especially effective for patients experiencing confusion.

The Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale (DVPRS) is a five-item tool that assesses the impact of pain on sleep, mood, stress, and activity levels (20).

For patients unable to self-report pain, such as those intubated in the ICU or late-stage neurological diseases, the FLACC scale is practical. The FLACC scale was initially created to assess pain in infants. Note: The patient need not cry to be rated 10/10.

| Behavior | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Face | No particular expression or smile | Occasional grimace or frown, withdrawn, disinterested | Frequent or constant quivering chin, clenched jaw |

| Legs | Normal position or relaxed | Uneasy, restless, tense | Kicking or legs drawn |

| Activity | Lying quietly, in a normal position, or relaxed | Squirming, shifting back and forth, tense | Arched, rigid, or jerking |

| Cry | No cry wake or asleep | Moans or whimpers: occasional complaints | Crying steadily, screams, sobs, frequent complaints |

| Consolability | Content, relaxed | Distractable, reassured by touching, hugging, or being talked to | Difficult to console or comfort |

(21).

Assess contributors to pain such as insomnia, stress, exercise, diet, and any comorbid conditions. Limited access to care, socioeconomic status, and local culture also contribute to the patient's experience of pain (23). Most patients have limited opportunity to discuss these issues, and though challenging to bring up, it is compassionate and supportive care. A referral to social work or another agency may be helpful if you cannot explore it fully.

Assess for substance abuse disorders, especially among male, younger, less educated, or unemployed adults. Substance abuse disorders increase the likelihood of misuse disorder and include alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, cocaine, and heroin (29).

Inquire as to what changes in function the pain has caused. One question to ask is, "Were it not for pain, what would you be doing?" As seen below, a Pain, Enjoyment, and General Activity (PEG) three-question scale, which focuses on function and quality of life, may help determine the severity of pain and the effect of treatment over time.

| What number best describes your pain on average in the past week? 0-10 |

| What number best describes how, in the past week, pain has interfered with your enjoyment of life? 0-10 |

| What number determines how, in the past week, pain has interfered with your general activity? 0-10 |

(21).

Assess family history, mental health disorders, chronic pain, or substance abuse disorders. Each familial aspect puts patients at higher risk for developing chronic pain (23).

Evaluate for mental health disorders the patient may be experiencing, particularly anxiety and depression. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ4) is a four-question tool for assessing depression and anxiety.

In some cases, functional MRI or imaging studies effectively determine the cause of pain and the treatment. If further assessment is needed to diagnose and treat pain, consult Neurology, Orthopedics, Palliative care, and pain specialists (23).

Case Study

You used OLDCARTS to evaluate Mary's pain and completed a body diagram. Mary is experiencing allodynia in her back and shoulders, described as burning and tingling. It is exacerbated when she lifts, such as moving patients at the long-term care facility and, more recently, boxes from her move to the new house. Mary has also been experiencing anxiety due to fear of losing her job, the move, and her new role. She has moved closer to her family to help care for her children since she often experiences fatigue. Mary has experienced a tumultuous divorce in the last five years and feels she is still undergoing some trauma.

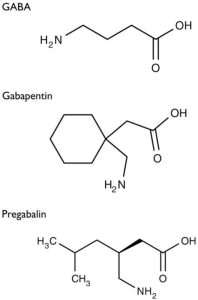

You saw in the chart that Mary had tried Gabapentin 300 mg BID for her pain and inquired what happened. Mary explained that her pain improved from 8/10 to 7/10 and had no side effects. Her previous care provider discontinued the medication and documented it as a failed therapy. You reviewed the minimum and maximum dosages of Gabapentin and know Mary can take up to 1800mg/day.

During the assessment, Mary also described stiffness and aching in her left knee. She gets a sharp pain when she walks more than 500 steps, and her knee is throbbing by the end of the day. Mary rated the pain a 10/10, but when she compared 10/10 to childbirth, Mary said her pain was closer to 6/10. Her moderate knee pain has reduced Mary's ability to exercise. She used to like to take walks. Mary stated she has had knee pain for six months and has been taking Ibuprofen 3 – 4 times daily.

Since Mary's pain is moderate, you evaluate your options of drugs for moderate to severe pain.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How do you assess and evaluate a patient's pain level?

- What are the different types of pain and their management strategies?

- How do you determine the appropriate dosage of pain medications for a patient?

- How do you assess the effectiveness of pain medications in your patients?

- How do you adjust medication dosages for elderly patients with pain or addiction?

- How do you address the unique challenges in pain management for pediatric patients?

- What is the role of non-pharmacological interventions in pain management?

- How do you incorporate non-pharmacological interventions into your treatment plans?

Opioid Classifications and Drug Schedules

A comprehensive understanding of drug schedules and opioid classifications is essential for nurse practitioners to ensure patient safety, prevent drug misuse, and adhere to legal and regulatory requirements. Nurse practitioners with a comprehensive understanding of drug schedules and opioid classifications can effectively communicate with colleagues, ensuring accurate medication reconciliation and facilitating interdisciplinary care. Nurse practitioners’ knowledge in facilitating discussions with pharmacists regarding opioid dosing, potential interactions, and patient education is essential (49).

Drug scheduling became mandated under the Controlled Substance Act. The Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) Schedule of Controlled Drugs and the criteria and common drugs are listed below.

|

Schedule |

Criteria | Examples |

|

I |

No medical use; high addiction potential |

Heroin, marijuana, PCP |

|

II |

Medical use; high addiction potential |

Morphine, oxycodone, Methadone, Fentanyl, amphetamines |

|

III |

Medical use; high addiction potential |

Hydrocodone, codeine, anabolic steroids |

|

IV |

Medical use, low abuse potential |

Benzodiazepines, meprobamate, butorphanol, pentazocine, propoxyphene |

| V | Medical use; low abuse potential |

Buprex, Phenergan with codeine |

(Pain Physician, 2008)

Listed below are drugs classified by their schedule and mechanism of action. "Agonist" indicates a drug that binds to the opioid receptor, causing pain relief and also euphoria. An agonist-antagonist indicates the drug binds to some opioid receptors but blocks others. Mixed antagonist-agonist drugs control pain but have a lower potential for abuse and dependence than agonists (7).

| Schedule I | Schedule II | Schedule III | Schedule IV | Schedule V | |

| Opioid agonists |

BenzomorphineDihydromor-phone, Ketobemidine, Levomoramide, Morphine-methylsulfate, Nicocodeine, Nicomorphine, Racemoramide |

Codeine, Fentanyl, Sublimaze, Hydrocodone, Hydromorphone, Dilaudid, Meperidine, Demerol, Methadone, Morphine, Oxycodone, Endocet, Oxycontin, Percocet, Oxymorphone, Numorphan |

Buprenorphine Buprenex, Subutex, Codeine compounds, Tylenol #3, Hydrocodone compounds, Lortab, Lorcet, Tussionex, Vicodin |

Propoxyphene, Darvon, Darvocet | Opium, Donnagel, Kapectolin |

| Mixed Agonist -Antagonist | BuprenorphineNaloxone, Suboxone |

Pentazocine, Naloxone, Talwin-Nx |

|||

| Stimulants | N-methylampheta-mine 3, 4-methylenedioxy amphetamine, MDMA, Ecstacy | Amphetamine, Adderal, Cocaine, Dextroamphetamine, Dexedrine, Methamphetamine, Desoxyn, Methylphenidate, Concerta, Metadate, Ritalin, Phenmetrazine, Fastin, Preludin | Benapheta-mine, Didrex, Pemolin, Cylert, Phendimetra-zine, Plegine | Diethylpropion, Tenuate, Fenfluramine, Phentermine Fastin | 1-dioxy-ephedrine-Vicks Inhaler |

| Hallucinogen-gens, other | Lysergic Acid Diamine LSD, marijuana, Mescaline, Peyote, Phencyclidine PCP, Psilocybin, Tetrahydro-cannabinol | Dronabinol, Marinol | |||

| Sedative Hypnotics |

Methylqualine, Quaalude, Gamma-hydroxy butyrate, GHB

|

Amobarbitol, Amytal, Glutethamide, Doriden, Pentobarbital, Nembutal, Secobarbital, Seconal |

Butibarbital. Butisol, Butilbital, Florecet, Florinal, Methylprylon, Noludar |

Alprazolam, Xanax, Chlordiazepoxide, Librium, Chloral betaine, Chloral hydrate, Noctec, Chlorazepam, Clonazepam, Klonopin, Clorazopate, Tranxene, Diazepam, Valium, Estazolam, Prosom, Ethchlorvynol, Placidyl, Ethinamate, Flurazepam, Dalmane, Halazepam, Paxipam, Lorazepam, Ativan, Mazindol, Sanorex, Mephobarbital, Mebaral, Meprobamate, Equanil, Methohexital, Brevital Sodium, Methyl-phenobarbital, Midazolam, Versed, Oxazepam, Serax, Paraldehyde, Paral, Phenobarbital, Luminal, Prazepam, Centrax, Temazepam, Restoril, Triazolam, Halcion, Sonata, Zolpidem, Ambien |

Diphenoxylate preparations, Lomotil |

(41).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are the potential risks and benefits of using opioids for pain management?

- How can nurse practitioners effectively monitor patients on long-term opioid therapy?

- What are the potential risks and benefits of using long-acting opioids for chronic pain?

- How do you monitor patients on long-acting opioids for safety and efficacy?

Commonly Prescribed Opioids, Indications for Use, and Typical Side Effects

Opioid medications are widely used for managing moderate to severe pain. Referencing NIDA (2023), this section aims to give healthcare professionals an overview of the indications and typical side effects of commonly prescribed Schedule II opioid medications, including hydrocodone, oxycodone, morphine, Fentanyl, and hydromorphone.

Opioids are derived and manufactured in several ways. Naturally occurring opioids come directly from the opium poppy plant. Synthetic opioids are manufactured by chemically synthesizing compounds that mimic the effects of a natural opioid. Semi-synthetic is a mix of naturally occurring and man-made (35).

Understanding the variations in how an opioid is derived and manufactured is crucial in deciding the type of opioid prescribed, as potency and analgesic effects differ. Synthetic opioids are often more potent than naturally occurring opioids. Synthetic opioids have a longer half-life and slower elimination, affecting the duration of action and timing for dose adjustments. They are also associated with a higher risk of abuse and addiction (38).

Hydrocodone

Mechanism of Action and Metabolism

Hydrocodone is a Schedule II medication. It is an opioid agonist and works as an analgesic by activating mu and kappa opioid receptors located in the central nervous system and the enteric plexus of the bowel. Agonist stimulation of the opioid receptors inhibits nociceptive neurotransmitters' release and reduces neuronal excitability (17).

- Produces analgesia.

- Suppresses the cough reflex at the medulla.

- Causes respiratory depression at higher doses.

Hydrocodone is indicated for treating severe pain after nonopioid therapy has failed. It is also indicated as an antitussive for nonproductive cough in adults over 18.

Available Forms

Hydrocodone immediate release (IR) reaches maximum serum concentrations in one hour with a half-life of 4 hours. Extended-release (ER) Hydrocodone reaches peak concentration at 14-16 hours and a half-life of 7 to 9 hours. Hydrocodone is metabolized to an inactive metabolite in the liver by cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP2D6 and CYP3A4. Hydrocodone is converted to hydromorphone and is excreted renally. Plasma concentrations of hydromorphone are correlated with analgesic effects rather than hydrocodone.

Hydrocodone is formulated for oral administration into tablets, capsules, and oral solutions. Capsules and tablets should never be crushed, chewed, or dissolved. These actions convert the extended-release dose into immediate release, resulting in uncontrolled and rapid release of opioids and possible overdose.

Dosing and Monitoring

Hydrocodone IR is combined with acetaminophen or ibuprofen. The dosage range is 2.5mg to 10mg every 4 to 6 hours. If formulated with acetaminophen, the dosage is limited to 4gm/day.

Hydrocodone ER is available as tablets and capsules. Depending on the product, the dose of hydrocodone ER formulations in opioid-naïve patients is 10 to 20 mg every 12 to 24 hours.

Nurse practitioners should ensure patients discontinue all other opioids when starting the extended-release formula.

Side Effects and Contraindications

Because mu and kappa opioid receptors are in the central nervous system and enteric plexus of the bowel, the most common side effects of hydrocodone are constipation and nausea (>10%).

Other adverse effects of hydrocodone include:

- Respiratory: severe respiratory depression, shortness of breath

- Cardiovascular: hypotension, bradycardia, peripheral edema

- Neurologic: Headache, chills, anxiety, sedation, insomnia, dizziness, drowsiness, fatigue

- Dermatologic: Pruritus, diaphoresis, rash

- Gastrointestinal: Vomiting, dyspepsia, gastroenteritis, abdominal pain

- Genitourinary: Urinary tract infection, urinary retention

- Otic: Tinnitus, sensorineural hearing loss

- Endocrine: Secondary adrenal insufficiency (17)

Hydrocodone, being an agonist, must not be taken with other central nervous system depressants as sedation and respiratory depression can result. In formulations combined with acetaminophen, hydrocodone can increase the international normalized ratio (INR) and cause bleeding. Medications that induce or inhibit cytochrome enzymes can lead to wide variations in absorption.

The most common drug interactions are listed below:

- Alcohol

- Benzodiazepines

- Barbiturates

- other opioids

- rifampin

- phenytoin

- carbamazepine

- cimetidine,

- fluoxetine

- ritonavir

- erythromycin

- diltiazem

- ketoconazole

- verapamil

- Phenytoin

- John’s Wort

- Glucocorticoids

Considerations

Use with caution in the following:

- Patients with Hepatic Impairment: Initiate 50% of the usual dose

- Patients with Renal Impairment: Initiate 50% of the usual dose

- Pregnancy: While not contraindicated, the FDA issued a black-boxed warning since opioids cross the placenta, and prolonged use during pregnancy may cause neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS).

- Breastfeeding: Infants are susceptible to low dosages of opioids. Non-opioid analgesics are preferred.

Pharmacogenomic: Genetic variants in hydrocodone metabolism include ultra-rapid, extensive, and poor metabolizer phenotypes. After administration of hydrocodone, hydromorphone levels in rapid metabolizers are significantly higher than in poor metabolizers.

Oxycodone

Mechanism of Action and Metabolism

Oxycodone has been in use since 1917 and is derived from Thebaine. It is a semi-synthetic opioid analgesic that works by binding to mu-opioid receptors in the central nervous system. It primarily acts as an agonist, producing analgesic effects by inhibiting the transmission of pain signals (Altman, Clark, Huddart, & Klein, 2018).

Oxycodone is primarily metabolized in the liver by CYP3A4/5. It is metabolized in the liver to noroxycodone and oxymorphone. The metabolite oxymorphone also has an analgesic effect and does not inhibit CYP3A4/5. Because of this metabolite, oxycodone is more potent than morphine, with fewer side effects and less drug interactions. Approximately 72% of oxycodone is excreted in urine (Altman, Clark, Huddart, & Klein, 2018).

Available Forms

Oxycodone can be administered orally, rectally, intravenously, and as an epidural. For this sake, we will focus on immediate-release and extended-release oral formulations.

- Immediate-release (IR) tablets

- IR capsules

- IR oral solutions

- Extended-release (ER) tablets

Dosing and Monitoring

The dosing of oxycodone should be individualized based on the patient's pain severity, previous opioid exposure, and response. Initial dosages for opioid naïve patients range from 5-15 mg for immediate-release formulations, while extended-release formulations are usually initiated at 10-20 mg. Dosage adjustments may be necessary based on the patient's response, but caution should be exercised. IR and ER formulations reach a steady state at 24 hours and titrating before 24 hours may lead to overdose.

Regular monitoring is essential to assess the patient's response to treatment, including pain relief, side effects, and signs of opioid misuse or addiction. Monitoring should include periodic reassessment of pain intensity, functional status, and adverse effects (Altman, Clark, Huddart, & Klein, 2018).

Side Effects and Contraindications

Common side effects of oxycodone include:

- constipation

- nausea

- sedation

- dizziness

- respiratory depression

- respiratory arrest

- hypotension

- fatal overdose

Oxycodone is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to opioids, severe respiratory depression, paralytic ileus, or acute or severe bronchial asthma. It should be used cautiously in patients with a history of substance abuse, respiratory conditions, liver or kidney impairment, and those taking other medications that may interact with opioids, such as alcohol (4).

It is also contraindicated with the following medications and classes:

- Antifungal agents

- Antibiotics

- Rifampin

- Carbamazepine

- Fluoxetine

- Paroxetine

Considerations

- Nurse practitioners should consider the variations in the mechanism of action for the following: