Course

Right and Left Sided Strokes

Course Highlights

- In this Right and Left Sided Strokes course, we will learn about the differences between ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes

- You’ll also learn between the effects of right and left-sided strokes in terms of motor function, sensory, and cognition deficits.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of nursing interventions for ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 3

Course By:

Abbie Schmitt, MSN-Ed, RN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

We are going to explore the fascinating world of brain function, where each hemisphere holds its own unique control over functions in the body. This course on right and left-sided strokes invites you to explore the intricate landscapes of the brain, revealing how strokes on either side create distinct challenges for clients and nurses alike. Learners will be able to spot the subtle clues that tell you which side of the brain has been affected—whether it’s a client struggling with speech or one unaware of their left side.

We will examine an unfolding case study, complete a mind-mapping activity, and virtually walk through an obstacle course designed to simulate deficits experienced with right and left-sided strokes. Whether it’s assisting a client with spatial awareness or helping someone find their voice again, learners will be prepared to meet the challenges that come with treating both right and left-sided strokes.

Definitions

It is important to review definitions as we create a foundation for understanding aphasia following a stroke. For this course, we will use the term “stroke”, which refers to a cerebrovascular accident (CVA). CVA is a recognized term in the medical community.

- Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) is the term for a stroke. This is essentially defined as the sudden death of brain cells due to lack of oxygen, caused by blockage of blood flow or rupture of an artery to the brain.

- Dysarthria: Slurred speech

- Hemorrhagic stroke: Occurs when a weakened vessel ruptures and bleeds into the brain.

- Ischemic stroke: Occurs when a blood vessel supplying blood to the brain is obstructed.

- Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA): a temporary blockage of blood supply within the brain (mini-stroke).

- Tissue Plasminogen Activator (tPA): An enzyme that helps dissolve clots.

Epidemiology

A sobering statistic is that about one individual in the United States has a stroke every 40 seconds (6). Since the beginning of this course, many people across our nation have likely begun experiencing a stroke.

According to the 2024 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics Update from the American Heart Association, approximately 795,000 Americans experience a stroke each year, with about 610,000 being first-time strokes and the rest being recurrent events (8).

Strokes are responsible for 1 of every 6 deaths resulting from cardiovascular disease (8).

Strokes are the second leading cause of death across the world (6) and the fifth leading cause of death in the U.S. (8).

Many who survive become temporarily or permanently disabled after the event.

Etiology

Many etiologies can cause a stroke. One of the most common causes is plaque formation secondary to low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) buildup within the arteries.

The most common risk factors include:

- Hypertension

- Diabetes mellitus

- Smoking

- Heart disease

Ischemia can be subdivided into three mechanisms: thrombosis, embolism, and decreased systemic perfusion. The most common causes of ischemic strokes are atherosclerosis, embolism, and small vessel disease, often linked to risk factors like hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease (2).

Thrombi can also develop in the areas where the internal carotid, middle cerebral arteries, and basilar arteries divide.

Emboli are thrombi formed at another distant site and travel to an artery of the brain. Embolic strokes are commonly caused by emboli that originate from the heart. Those with heart arrhythmias (atrial fibrillation), valvular disease, structural defects (atrial and ventricular septal defects), and rheumatic fever are at greater risk. Emboli typically wedge in areas of preexisting stenosis. (7)

Strokes that occur in small vessels are most commonly caused by chronic, uncontrolled hypertension and arteriosclerosis. These strokes occur in the basal ganglia, internal capsule, thalamus, and pons. (7)

A plumbing analogy can help learners to understand the differences among the mechanisms of ischemia. A pipe can be partially or completely occluded due to a local occlusion process, similar to a blood vessel obstructed due to a thrombus. A pipe may also be blocked by an object from elsewhere in the system, such as the water tank, which is an example of an embolism. The third mechanism of intermittently low-pressure results in the low flow of water to the sinks, similar to poor systemic perfusion.

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy is a disease in which amyloid plaques deposit in small and medium vessels, causing the vessels to become rigid and more vulnerable to tears. This condition is also a causative factor of hemorrhagic strokes (7). The plaques are most commonly deposited on the surfaces of the frontal and parietal lobes.

Hemorrhagic strokes are also caused by aneurysms, arteriovenous malformations, cavernous malformations, capillary telangiectasias, venous angiomas, and vasculitis (7).

Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA)

A Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA), often referred to as a “mini-stroke,” occurs when there is a temporary reduction or blockage of blood flow to the brain, similar to a stroke. However, unlike a full stroke, the blockage in a TIA is brief, typically lasting only a few minutes to an hour, and does not cause permanent damage to brain tissue. Symptoms of a TIA are similar to those of a stroke, such as sudden weakness or numbness (often on one side of the body), difficulty speaking, loss of coordination, dizziness, and vision problems. However, they resolve within 24 hours, usually within minutes. TIAs are considered serious warning signs of a possible upcoming stroke. Approximately 1 in 3 people who experience a TIA have a full stroke later on, with about 50% of those occurring within a year after the TIA (13).

Clients presenting to an emergency department 1 to 2 hours after the onset of ischemic symptoms are very likely to have a stroke because most TIAs begin to resolve within minutes to a few hours (13).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you name risk factors that contribute to strokes?

- Why is it important to control hypertension?

- What is the difference between a TIA and a stroke?

- Where are common locations where emboli that travel to the brain originate from?

Review of Stroke Pathophysiology

A stroke is the result of an interruption in blood supply to brain tissue, leading to brain cell death.

There are two primary types of strokes: ischemic and hemorrhagic.

Ischemic stroke is caused by a blockage in a blood vessel, leading to reduced blood flow and oxygen delivery to brain tissue. This is the most common type of stroke.

Ischemic strokes are more common and account for 87% of all strokes (14). Ischemic strokes are classified as (1) large vessel, atherothrombotic strokes; (2) small vessel or lacunar thrombotic strokes; (3) cardioembolic strokes; (4) strokes caused by a variety of clinically definite but less common mechanisms; and (5) cryptogenic strokes, or those for which a precise mechanism or cause is not discovered (13).

Hemorrhagic strokes are when a blood vessel ruptures, leading to bleeding in or around the brain, which then damages brain tissue. Hemorrhagic strokes are categorized into two main types based on where the bleeding occurs within or around the brain: (1) Intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) and (2) Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH) (14).

- Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ICH)

- Bleeding occurs within the brain tissue itself, often resulting from the rupture of small arteries or arterioles.

- Common causes include chronic hypertension, trauma, blood vessel abnormalities, or blood-thinning medications.

- Symptoms typically include a sudden onset of a headache, weakness on one side of the body, difficulty speaking, loss of coordination, and altered consciousness.

- Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH)

- This bleeding occurs in the subarachnoid space, which is the area between the brain and the meninges (thin tissues that cover the brain).

- The most common cause is the rupture of an aneurysm. Additional causes include trauma, blood vessel malformations, or bleeding disorders.

- Symptoms include a sudden, severe headache often described as the “worst headache of my life,” nausea and vomiting, neck stiffness, sensitivity to light, seizures, and loss of consciousness.

Extradural hemorrhage usually occurs after head trauma in younger clients; the most common occurrence is a skull fracture that tears a dural artery (13). Sometimes a period of normal cognition occurs between the head injury and the development of symptoms as the blood accumulates.

Subdural hemorrhage (SDH) also occurs most often after trauma. Symptoms of a subacute or chronic SDH may develop gradually (14). Chronic SDH is more common in elderly clients in whom brain atrophy leaves a space between the brain and the skull. Drowsiness and subtle neurologic changes are the hallmarks of SDH.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is usually caused by a rupture of a cerebral aneurysm. Headache and stiff neck are the most common symptoms of SAH, although a variety of other syndromes can occur.

Both intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhages are medical emergencies that require rapid diagnosis and treatment to minimize brain damage and improve client outcomes.

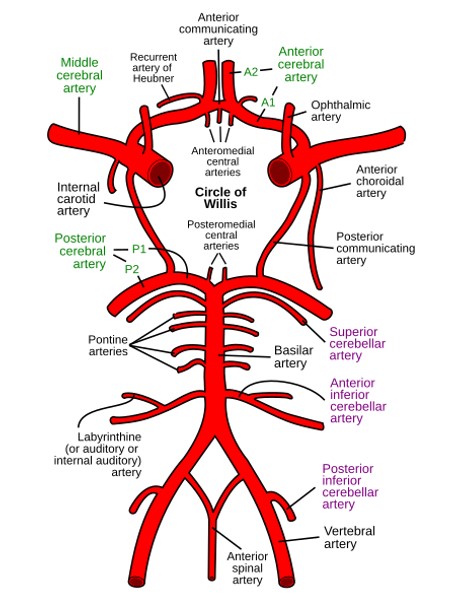

Cerebral Vascular Supply

It is vital to understand cerebral vascular blood flow when evaluating strokes. Knowing what vessels provide blood flow to each area of the brain is critical.

The brain receives its blood supply from the internal carotid arteries (ICAs) and the vertebral arteries (VA). The ICAs handle anterior circulation, and the VAs handle posterior circulation.

The circle of Willis is an anastomotic system of arteries located at the base of the brain connecting anteroposterior and bilateral flows. The right innominate artery, the left common carotid artery (CCA), and the subclavian artery originate from the aortic arch.

This system is divided in the following ways:

- The right innominate artery is then divided into the right CCA and right subclavian artery.

- The right VA originates from the right subclavian artery and the left VA from the left subclavian artery.

- The CCA bifurcates to the ICA and the external carotid artery (ECA) at the level of the C4 vertebral body.

Image 1. Cerebral Vascular Anatomy and the Circle of Willis (12)

Image 1. Cerebral Vascular Anatomy and the Circle of Willis (12)

The specific symptoms of a stroke depend on the area of the brain affected by the disruption of blood flow. For example, damage to the left hemisphere often results in speech and language deficits, while right hemisphere strokes may cause spatial and perceptual difficulties.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you describe the pathway of blood in vessels in the brain?

- How would you explain the difference between a hemorrhagic and an ischemic stroke?

- What are the two subtypes of hemorrhagic stroke?

- How can TIAs be differentiated from CVAs?

General Clinical Presentation: Signs and Symptoms

The presentations of stroke vary from person to person. They reflect the type, severity, and location of the tissue impact. When an area of the brain is damaged from a stroke, the part of the body it controls may lose normal function.

The effects of a stroke depend on the location where it occurs.

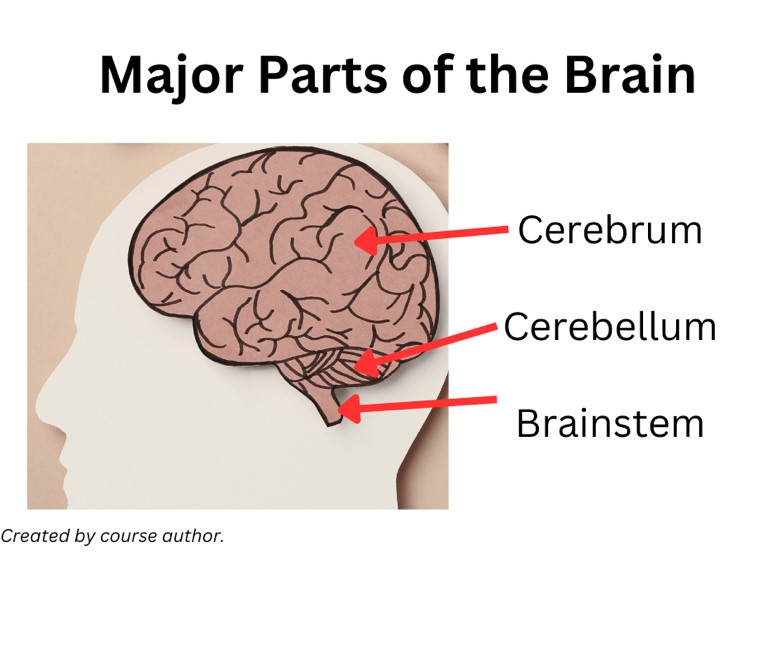

The brain has 3 main areas:

- Cerebrum – the largest portion of the brain

- Cerebellum – the area at the back of the brain

- Brainstem – the area at the base of the brain

The cerebrum is divided into two hemispheres, the right and left, and each controls the opposite side of the body. It is responsible for higher brain functioning, such as thought, reasoning, memory, sensation, voluntary movement, and emotional responses (2).

The cerebellum is beneath and behind the cerebrum at the back portion of the brain. It receives sensory information from the body from the spinal cord and supports muscle action and control. It also controls fine movement, coordination, and balance. Strokes are less common in the cerebellum region; however, the effects can be severe.

Common effects of strokes in the cerebellum include (2):

- Unable to walk

- Ataxia (difficulty with coordination and balance)

- Dizziness

- Headache

- Nausea and vomiting

The brainstem is at the base of the brain, right above the spinal cord. The brainstem impacts vital “life-support” functions. These include pulse rate, blood pressure, and breathing (13). It also supports the nerves involved in eye movement, hearing, speech, chewing, and swallowing.

Common effects of a stroke in the brainstem include (2):

- Respiratory and cardiac abnormalities

- Abnormal body temperature control

- Balance and coordination problems

- Weakness

- Coma

- Death

The key to differentiating types is early gait ataxia. Clients who are dizzy from vestibular function can typically walk as they normally do, but clients with cerebellar hemorrhage typically cannot. Bleeding into the basal ganglia usually causes hemiparesis (3).

The effects of a stroke can be broken down into physical, cognitive, emotional, and sensory impacts. This distinction can help in assessing the full scope of stroke-related impairments and guide rehabilitation and treatment.

Stroke symptoms reflect dysfunction of focal areas of the brain that are affected. In hemorrhage, the location of the bleeding helps determine the stroke syndrome.

When a stroke occurs at the brain stem, it can affect both sides of the body.

Some generalizations can be made about the deficits incurred with left-sided and right-sided strokes.

| Vessels Involved in Stroke and their Correlating Signs and Symptoms | |

| Internal carotid artery (ICA) syndrome |

|

| Middle cerebral artery (MCA) syndrome |

|

| Anterior cerebral artery (ACA) syndrome |

|

| Vertebral artery syndrome |

|

| Anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) syndrome |

|

| Posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) syndrome |

|

Table 1. Vessels Involved in Stroke and their Correlating Signs and Symptoms (14)

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are the major portions of the brain?

- How is damage to the cerebrum commonly manifested?

- How is damage to the cerebellum commonly manifested?

- What is particularly unique about the signs and symptoms of damage to the brain stem?

Case Study: Mrs. T

Mrs. T is a 62-year-old who awoke early this morning with a severe bout of vertigo. She made a trip to the restroom but suddenly needed to grab onto the wall and furniture to get back to bed, yelling for her husband to help her. Mrs. T’s husband felt like something was wrong, he thought her left hand was significantly weaker as she grabbed his hand for support. The vertigo continued and was soon accompanied by nausea and vomiting. They decided to go to the nearby ED. Mrs. T’s medical history includes hypertension, hyperlipidemia, depression, and hypothyroidism. She was diagnosed with a TIA six months ago, with symptoms resolving after the event.

Upon arrival at the ED, Mrs. T seemed to be more concerned about her dizziness, she and her husband forgot to mention the left-sided weakness, so the ED staff initially focused on her dizziness and nausea with supportive care. However, the nurse completed a neurological exam and found worrisome moderate left upper extremity weakness and dysmetria, which she notified the ED provider immediately. Mrs. T continued to deteriorate neurologically over the next hour with disorientation and a loss of consciousness.

- Have you ever cared for a client who thought certain symptoms were more concerning, but you recognized and prioritized other signs and symptoms?

- What do you consider Mrs. T’s most concerning sign?

- Are you familiar with neurological assessment tools?

- What assessment questions would be helpful in this case?

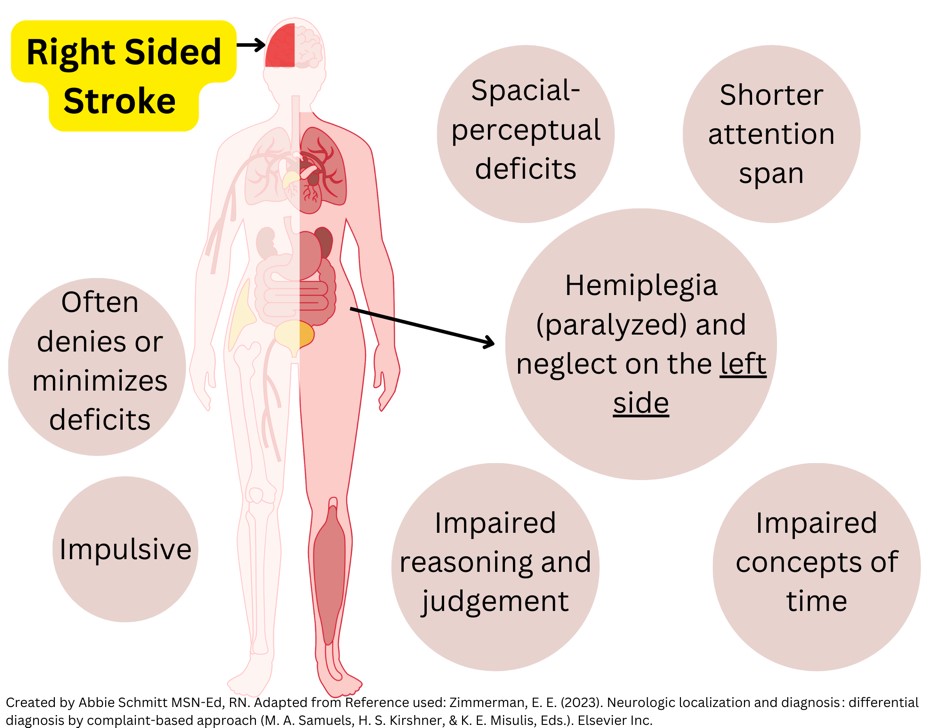

Right-Sided Strokes

A right-sided stroke happens when there is an interruption in blood flow to the right hemisphere of the brain, which controls the left side of the body. In both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes, reduced cerebral blood flow deprives brain cells of oxygen and glucose, initiating cell death. This damage disrupts neuronal circuits, which leads to the classic symptoms of motor, sensory, and cognitive impairments on the opposite side of the stroke site.

Strokes on the right side are typically caused by an occlusion in the right middle cerebral artery (MCA), the right anterior cerebral artery (ACA), or the right posterior cerebral artery (PCA). These arteries supply different brain regions that manage motor control, sensory input, and cognitive functions. This area of the brain is also responsible for spatial awareness, creativity, and non-verbal communication (14).

Motor and Sensory Deficits

Some motor and sensory deficits include (13, 14):

- Left-sided Hemiparesis

- Hemiparesis refers to weakness or partial paralysis. This condition affects motor control and movement, but unlike complete paralysis, some voluntary muscle movement still occurs, although it is often reduced or limited in strength.

- Hemiparesis is typically caused by damage to the brain’s motor pathways.

- Symptoms may include:

- Difficulty lifting objects, walking, or maintaining balance on the affected side.

- Diminished strength in the arm, leg, or both on the left side, causing an uneven gait or difficulty performing daily activities.

- Left-sided Hemiplegia

- Hemiplegia is complete paralysis in which the individual cannot move the affected limbs (either the arm, leg, or both) on that side.

- Symptoms include:

- Total loss of movement, loss of sensation, and difficulties with balance and posture.

- The affected side may be flaccid (limp) or spastic (stiff and difficult to move).

- Left-sided Neglect

- Unaware of objects or even the body’s left side, due to damage in the right parietal lobe.

- Impaired

- Impaired Proprioception

- Difficulty in recognizing the position of the left side of the body.

Cognitive Effects

Neuropsychiatric deficits and cognitive impairment are among the most common and severe consequences of stroke (4). A survey found that cognition-related disturbances were the highest priority concern among stroke survivors, caregivers, and medical professionals (4).

Clients may struggle with depth and special perception. This may manifest as confusion within their physical environment, not being able to decipher distances. This makes tasks like dressing, reaching for items, or navigating spaces difficult.

Anosognosia is a common feature of right-sided strokes, where the client is unaware of their deficits, particularly left-sided weakness. It is common for these individuals to minimize or deny deficits (13). Due to lacking acknowledgment that they are unable to continue normal activities, these clients are at higher risk for injury due to being less cautious and often more impulsive.

Poststroke dementia is a cognitive decline that develops after a stroke. Poststroke dementia affects various cognitive functions, including memory, attention, executive function, and language skills. Clients may struggle with tasks that were previously easy, like managing finances, following a conversation, or navigating familiar places.

Emotional Effects

Clients may exhibit impulsive or erratic behavior, often due to damage in areas that regulate judgment and emotional responses (14).

Physical / Hemodynamic Effects

Right-sided strokes can also affect the right occipital lobe, causing left homonymous hemianopia, where the client loses the left field of vision in both eyes.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Is a client with a right-sided stroke more likely to exhibit cautious or impulsive behavior?

- Why does tissue damage to the right side of the brain cause effects on the left side of the body?

- Can you describe the cognitive effects of right-sided strokes?

- Can you describe the difference between hemiparesis and hemiplegia?

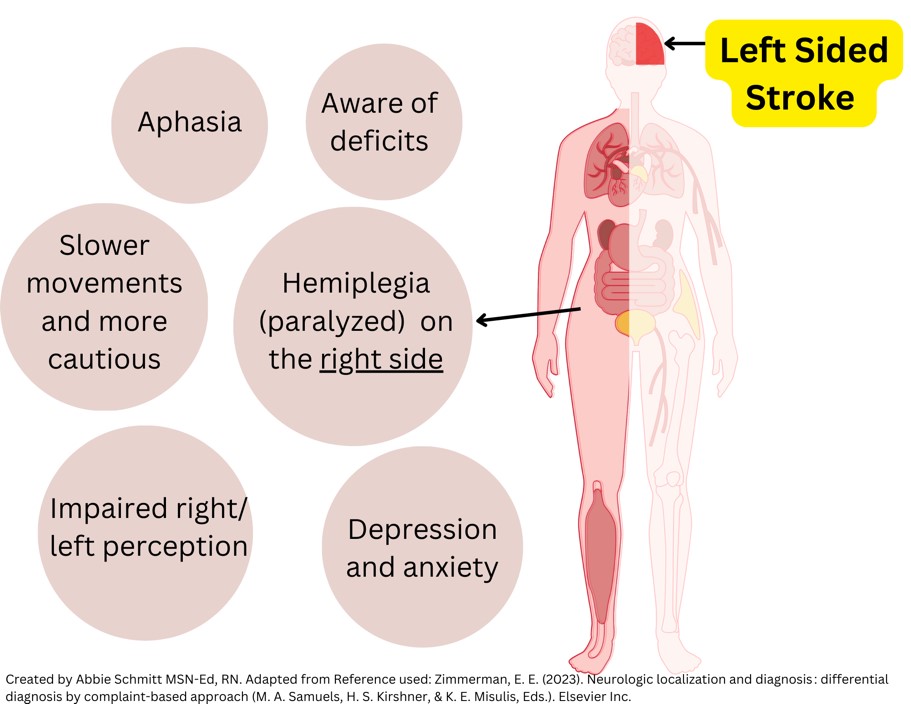

Left-Sided Strokes

A left-sided stroke happens when there is an interruption in blood flow to the left hemisphere of the brain, which controls the right side of the body. This damage also disrupts neuronal circuits, which leads to the classic symptoms of motor, sensory, and cognitive impairments on the opposite side of the stroke site (14).

Motor and Sensory Deficits

Motor and sensory deficits for left-sided strokes include (13):

- Right-sided Hemiparesis

- Right-sided Hemiplegia

- Right-sided Neglect

- Vision changes, including the loss of the right field of vision in both eyes

Cognitive Effects

- Inability to organize, reason, analyze, or do mathematical problems

- Behavior changes, such as being cautious and hesitant

- Impaired ability to read, write, and learn new information

- Memory problems

- Aphasia

Aphasia is characterized by difficulty in speaking, understanding speech, reading, or writing. Aphasia is much more common with left-sided strokes than right-sided strokes. This is because the left hemisphere of the brain is typically responsible for language and speech among most individuals. Broca’s area (speech production) and Wernicke’s area (language comprehension) are locations for these processing functions. Types of aphasia include (14):

- Broca’s Aphasia – Difficulty with speech production and the ability to understand language relatively intact.

- Wernicke’s Aphasia – Difficulty understanding spoken or written language, often with fluent but nonsensical speech.

- Global Aphasia – Impaired speech production and comprehension. This is typically a result of extensive damage to the left hemisphere.

Emotional Effects

Clients may struggle with a new onset of depression, mood changes, and anxiety. Behavioral changes may be noted in more cautious or prudent behavior.

Physical / Hemodynamic Effects

Left-sided strokes can also affect the right occipital lobe, causing left homonymous hemianopia, where the client loses the left field of vision in both eyes.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Is a client with a left-sided stroke more likely to exhibit cautious or impulsive behavior?

- Can you describe the different types of aphasia?

- What are the common emotional effects of left-sided strokes?

- How can depression and anxiety impact overall well-being and recovery?

Assessment

Several assessment tools are used to evaluate stroke clients to help diagnose the type, severity, and location of the stroke. These tools guide clinical decision-making and help evaluate client progress.

NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS)

The NIH Stroke Scale is a widely used tool that quantifies the severity of a stroke by evaluating neurological impairments. It assesses the following 11 domains: consciousness, visual fields, facial palsy, motor function, sensory abilities, coordination, language, and inattention (neglect). Scores range from 0 (normal function) to 42 (severe stroke). A higher score indicates greater stroke severity (9).

This scale, found here, is used in acute stroke settings, especially to determine eligibility for thrombolytic therapy (tPA) and to monitor neurological changes over time. (9)

Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)

The GCS assesses the level of consciousness in clients, which is particularly useful for clients who may be unconscious or unable to communicate during or following a stroke. It evaluates eye-opening, verbal response, and motor responses. The GCS is often used in conjunction with other stroke assessments to evaluate neurological status, especially in hemorrhagic stroke clients.

Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale (CPSS)

The CPSS is used by first responders and healthcare providers to quickly identify potential strokes in the prehospital setting.

It assesses three main symptoms of stroke:

- Facial droop (ask the client to smile)

- Arm drift (ask the client to raise both arms)

- Speech impairment (ask the client to repeat a short sentence)

Several studies have determined the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale (CPSS) to be an effective tool to rapidly assess for potential stroke cases (1). However, further evaluation and neurological assessments by the nurse and provider are essential.

FAST (Face, Arms, Speech, Time)

FAST is a simple, widely recognized method used to identify stroke symptoms quickly. This is a terrific teaching tool for clients and families.

Components:

- Face: Ask the person to smile—check for facial droop.

- Arms: Ask the person to raise both arms—look for arm drift.

- Speech: Ask the person to repeat a sentence—listen for slurred or strange speech.

- Time: Collect the time symptoms started and seek emergency medical attention immediately.

The Barthel Index (BI) and Modified Rankin Scale (mRS)

The Barthel Index (BI) and Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) are tools in stroke rehabilitation to measure a client’s functional independence and recovery after a stroke.

The Barthel Index is used to measure a client’s ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs). It evaluates physical functioning and independence in everyday tasks.

- Feeding

- Bathing

- Dressing

- Toileting

- Mobility (walking or wheelchair use)

- Climbing stairs

- Continence (bladder and bowel control)

The Barthel Index assigns a score ranging from 0 (complete dependence) to 100 (complete independence). Higher scores indicate greater independence.

The Modified Rankin Scale measures a client’s level of disability or dependence in performing daily activities, specifically after a stroke. This tool focuses on overall physical, cognitive, and social factors.

These tools also predict long-term outcomes and goals for rehabilitation.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Have you performed an NIH Stroke Scale Assessment before?

- How would you describe an “abnormal” finding regarding speech changes, when compared to baseline?

- What is an appropriate question to ask when assessing facial symmetry?

- Why are effective tools to evaluate functional abilities important following a stroke?

Diagnostic Tools

The first step of stroke diagnosis, after clinical assessment, is a brain imaging study. Imaging includes (3, 4):

- Computed Tomography

- The CT scan has traditionally served as the primary diagnostic test.

- CT can detect hemorrhage early and delineate the location and extent of an ischemic lesion

- It may take 2 to 3 days before a cerebral infarction becomes visible on CT and is less sensitive for the detection of early infarct changes than MRI.

- CT Angiogram

- Imaging the cerebral and neck vessels with contrast infusion, CT perfusion studies, and mapping areas of cerebral blood flow after contrast infusion such that areas of extremely low blood flow are assumed to be associated with irreversible infarction.

- CT Venogram

- CT venogram also includes injection of iodinated dye followed by a CT scan, but the timing of acquisition differs from CTA so that the veins are revealed.

- This is most commonly used if intracranial venous sinus thrombosis is suspected.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

- The use of acute MRI scanning can delineate areas of ischemia very early in ischemic stroke via the diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) modality.

- Other brain imaging techniques include single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET) scanning. Doppler ultrasound technology allows real-time ultrasound imaging of the carotid bifurcations and Doppler signal analysis of blood flow. This technique is still somewhat experimental.

- Transcranial Doppler (TCD) can visualize flow in the major intracranial arteries.

- Catheter Angiography – the traditional catheter arteriogram is the gold standard of vascular diagnosis; iodinated contrast can be injected directly into cerebral vessels, usually via femoral artery catheterization, and the arteries of the neck and brain can be imaged by standard radiographic technology.

- Cardiac Imaging – A thorough evaluation of the source of a stroke also involves examining the heart, looking for a source of embolism to the brain.

- Electrocardiography (ECG) and heart rhythm monitoring are useful in stroke clients because arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation can occur intermittently. Echocardiography images look for a thrombus within the left atrium or ventricle.

- Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), in which the ultrasound probe is placed in the esophagus directly behind the heart allows more accurate diagnosis of cardiac conditions.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Why is it important to closely examine the heart and possible sources of an emboli?

- Which diagnostic study is typically considered the primary tool in stroke evaluation and diagnosis?

- What are some nursing interventions to prepare clients for these imaging procedures?

- What is the diagnostic tool for vascular diagnosis?

Laboratory Studies

An important portion of clinical evaluation in stroke clients involves blood tests.

A complete blood count (CBC) is always indicated in stroke clients. Elevated platelet counts (thrombocytosis) can lead to clotting in cerebral vessels, whereas low levels of platelets (thrombocytopenia) can lead to bleeding.

Tests to measure clotting, including the prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT), can detect clotting defects that lead to cerebral hemorrhage. Additional clotting tests are available. The lupus anticoagulant is associated with arterial clotting and stroke syndromes. Other tests to evaluate hypercoagulability are related to venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism; these include proteins C and S, antithrombin III, factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene mutation, and others.

Elevated homocysteine levels correlate with a higher risk of stroke.

Blood tests for endocrine, metabolic, and organ function are meaningful in stroke evaluation.

Plasma lipids help evaluate the risk of both myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke. Fasting total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and triglycerides should be tested in all stroke clients.

Case Study: Mrs. T

Mrs. T’s STAT CT scan of the head with angiography and perfusion revealed an embolus in the posterior portion of the brain and a large left cerebellar infarct. She gained consciousness but denies the obvious weakness and loss of strength in her right upper and lower extremities; the nurse noted continued altered mental status and speech changes.

- Can you discuss the results and meaning of the CT scan results?

- Would this stroke be considered ischemic or hemorrhagic?

- What do you anticipate the treatment options for this type to be?

- What supportive and safety interventions are most important at this time?

Management Strategies

Recovery depends on the location and severity of the stroke, early detection, and intervention. Treatments such as thrombolytics (for ischemic strokes), rehabilitation therapy, and long-term care play a huge role in recovery and minimizing long-term deficits.

Before any treatment can be administered, the client must be assessed for a stable airway, breathing, and circulation.

Ischemic Stroke

The first-line treatment for clients with an ischemic stroke is intravenous thrombolytic therapy, which is administered as an IV bolus of alteplase given over 1 minute, followed by an infusion over 60 minutes (11). It is important to be aware of the exclusion criteria for this treatment, which is based on guidelines from the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association.

This therapy aims to dissolve the clot and restore blood flow to the affected regions.

Important points regarding IV thrombolytics:

- Time management is of the utmost importance in clients because the fibrinolytic/thrombolytic therapy must be administered within 3 to 4.5 hours after symptom onset to be effective.

- Within 24 to 48 hours of symptoms onset, clients should be placed on oral anti-platelet therapy, typically 325 mg of aspirin.

- Blood pressure should be maintained at slightly higher levels for counter vasoconstriction. Blood pressure should also be lowered gradually over the few days following to treat underlying hypertension.

- Significant advancements have been made in recent years with the emergence of mechanical thrombectomy to remove the occluding clot and reestablish blood flow to the brain.

Alteplase (tPA) is a powerful thrombolytic agent used in the lysis of acute thromboembolism. FDA-approved indications for alteplase include pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation (STEMI), ischemic stroke when given within 3 hours of the start of symptoms, and re-establishment of patency in occluded intravenous (IV) catheters. (5)

- Adverse Effects of tPA (5):

- The most frequent serious adverse events associated with the administration of tPA are related to bleeding

- Internal bleeding includes intracranial, retroperitoneal, gastrointestinal (GI), genitourinary, and respiratory bleeding.

- Superficial bleeding mainly includes ecchymosis, gingival bleeding, and epistaxis.

- Cardiac dysrhythmias can occur

- Allergic reactions, including anaphylactic-type reactions, are possible following exposure to tPA.

- Contraindications of tPA: The American Heart Association (AHA) provides guidance on tPA inclusion and exclusion criteria for the management of ischemic stroke. Exclusion Criteria (5):

- Severe head trauma in the previous 3 months

- Prior stroke in the previous 3 months

- Suspected subarachnoid hemorrhage

- An arterial puncture at a noncompressible site in the previous 7 days

- A history of intracranial hemorrhage, intracranial neoplasm, AVM, or an aneurysm

- Recent intracranial or intraspinal surgery

- Elevated blood pressure (systolic greater than 185 mmHg or diastolic greater than 110 mmHg)

- Active internal bleeding

- Platelet count less than 100 000/mm^3

- Heparin was received within 48 hours, resulting in abnormally elevated aPTT above the upper limit of normal

- Current use of anticoagulant with INR greater than 1.7 or PT greater than 15 seconds

- Current use of direct thrombin inhibitors or direct factor Xa inhibitors with elevated sensitive laboratory tests (e.g., aPTT, INR, platelet count, ECT, TT, or appropriate factor Xa activity assays)

- Blood glucose less than 50 mg/dL (2.7 mmol/L)

- CT demonstrates multilobar infarction (hypodensity greater than a one-third cerebral hemisphere)

- Consider and weigh the risk to the benefit of intravenous rtPA administration carefully for these relative contraindications (5):

- Only minor or quickly improving stroke symptoms

- Pregnancy

- Seizure at the onset with postictal residual neurological impairments

- Major surgery or serious trauma (within 14 days)

- Recent GI or urinary tract hemorrhage (within 21 days)

- Recent acute myocardial infarction (within 3 months)

Hemorrhagic Stroke

Most clients with this type of stroke are managed with interventions that focus on relieving intracranial pressure. This is often done by ventricular drain placement and/or a craniotomy (11). Catheter-directed intracranial intervention for a spontaneous hemorrhagic stroke may be performed.

Clients who were previously on anticoagulation agents will need to reverse this coagulopathy using reversal agents and plasma product transfusions (11). Coagulation studies must be followed closely, and medication adjustments made accordingly.

Blood pressure control is a critical aspect of management. Some clients may also be placed on seizure medications prophylactically.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How do treatments for ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes differ?

- Why is BP control so important for both types of stroke management interventions?

- Are you familiar with your facility’s policy on tPA therapy?

- What are specialists and disciplines that would be consulted during and following a stroke?

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for stroke clients focus on providing immediate care, preventing complications, and promoting rehabilitation to restore function. These interventions are critical in both the acute phase of stroke and long-term recovery.

Below are key nursing interventions for stroke clients:

- Assess mental status and level of consciousness

- Perform frequent neurological assessments

- Assess respiratory and cardiac function

- Monitor vital signs

- Assess higher functions like speech, memory, and cognition

- Provide a quiet environment with the head of the bed elevated

- Implement fall precautions such as non-slip socks and leaving the call bell within reach

- Prevent constipation and straining with stool softeners as needed

- Provide deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis

Nursing Goals and Interventions

- Acute Care and Safety Monitoring

- Airway Management

- Ensure that the client has a clear airway to prevent aspiration.

- Suctioning, if necessary, and positioning to maintain a patent airway.

- Neurological Monitoring

- Regular assessments using tools like the NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) to monitor the client’s neurological status, including changes in consciousness, motor function, and sensory deficits.

- Blood glucose control

- Hyperglycemia can negatively impact stroke outcomes, so blood sugar should be managed within appropriate limits.

- Prevention of Complications

- Positioning

- Proper positioning can help prevent pressure ulcers, aspiration pneumonia, and contractures.

- Elevate the head of the bed (30 degrees or higher) to prevent aspiration and reduce intracranial pressure.

- Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) Prevention

- Use compression devices or administer ordered anticoagulants, if appropriate, to prevent DVT relating to reduced activity.

- Nutrition and Hydration

- Swallowing Assessment

- The swallowing assessment is designed to prevent aspiration. A speech-language pathologist can be contacted for further evaluation. Nurses can also become skilled in swallowing tests.

- Enteral Feeding

- If the client is unable to swallow safely, provide enteral feeding through a nasogastric or gastrostomy tube to ensure nutritional needs are met

- Maintain hydration through intravenous fluids or enteral feeding while monitoring for signs of dehydration or fluid overload.

- Fall Prevention: Implement safety measures such as bed alarms, assistive devices (e.g., walkers), and frequent monitoring to reduce fall risk.

- Mobility and Comfort Measures

- Early Mobilization: Initiate passive and active range-of-motion exercises as early as possible to prevent muscle atrophy and joint stiffness.

- Positioning for Hemiplegia/Hemiparesis: Support the affected side using pillows to prevent contractures and encourage the use of the unaffected side.

- Communication and Cognitive Support

- Facilitating Communication

- For those with aphasia or communication challenges, speech therapists are a valuable resource for providing alternative methods of communication.

- Tools can include communication boards or writing tools.

- Cognitive Stimulation

- Memory games or simple problem-solving tasks can help to improve cognitive function during recovery.

- Emotional and Psychosocial Support

- Emotional Support: Stroke can lead to frustration, depression, and anxiety. Provide emotional support, encourage participation in support groups, and consider referrals to mental health professionals.

- Family Involvement

- Encourage family participation in care planning and education about the client’s needs, including recognizing signs of stroke recurrence and the importance of rehabilitation.

- Provide education to the client and family members about stroke symptoms, treatment, and rehabilitation plans. Include instructions on preventing future strokes, managing risk factors (e.g., hypertension, diabetes), and medication adherence.

- Discharge Planning

- Rehabilitation

- Collaborate with the interdisciplinary team to develop a discharge plan that may include referrals to physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy.

- Home safety evaluation

- Evaluation of the home environment regarding client safety upon discharge is paramount, including installing grab bars, removing falling hazards, and setting up home care services if necessary.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are airway management interventions?

- Why is it important to manage glucose levels following a stroke?

- Can you name interventions and strategies to prevent trips and falls?

- Which discipline(s) can conduct the swallowing test for stroke clients?

Case Study: Mrs. T

Given that Mrs. T arrived within the 4.5-hour window for ischemic stroke treatment, the medical team followed the acute stroke protocol:

A tissue Plasminogen Activator (tPA) was administered to dissolve the clot and restore blood flow to the affected brain tissue. tPA was delivered intravenously as Mrs. T met the eligibility criteria, and no contraindications were identified.

Mrs. T’s blood pressure was elevated upon arrival (165/100 mmHg). While managing her stroke, your medical team carefully monitored her blood pressure to ensure that it was not too low to compromise cerebral perfusion but controlled to reduce the risk of further damage. Her blood sugar was elevated, so an insulin drip was initiated to keep her glucose levels within a safe range.

Post-Acute Care (12:30 PM): After the administration of tPA, Mrs. T was closely monitored in the intensive care unit (ICU) for signs of improvement or complications, such as hemorrhage. Over the next 24 hours, her neurological status improved, with a partial return of movement and sensation in her left extremities.

- Can you discuss the contraindications for tPA therapy?

- What are the side/adverse effects of tPA therapy that the nurse should monitor Mrs. T for?

Rehabilitation

After a stroke, a major aspect of healing is the integration of physical therapy (PT), occupational therapy (OT), and speech therapy (ST) to aid in recovery. These therapies focus on helping clients regain functions and improve their quality of life.

Physical Therapy

Physical Therapy (PT) focuses on improving mobility, strength, and balance. PT helps clients regain movement in the affected limbs. (10)

Activities include:

- Strength exercises for weakened muscles to improve mobility and reduce spasticity.

- Balance training to prevent falls by improving coordination and posture.

- Gait training to support learning to walk again and using assistive devices like walkers or canes.

Occupational Therapy

Occupational Therapy (OT) focuses on helping stroke survivors relearn daily living skills to become more independent. These activities include self-care tasks like dressing, bathing, cooking, and toileting. (10)

Activities include:

- Fine motor skills exercises: For tasks like buttoning clothes or handling small objects.

- Cognitive retraining: For clients who have difficulty with memory, problem-solving, or attention due to the stroke.

- Adaptations for independence: Introducing assistive devices or modifying the home environment (e.g., grab bars, raised toilet seats) to support independence.

Speech Therapy

Speech Therapy (ST) helps stroke survivors with communication difficulties, especially those who have aphasia, dysarthria, or swallowing problems. (10)

Activities include:

- Speech exercises support language skills, including word-finding, sentence construction, and clarity of speech.

- Swallowing therapy for dysphagia applies exercises to strengthen the muscles used in swallowing to prevent aspiration.

- Cognitive communication therapy uses strategies to improve memory, attention, or problem-solving related to communication.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are the goals and activities of PT?

- What are the goals and activities of OT?

- What are the goals and activities of ST?

- How can nurses support these disciplines?

Case Study: Mrs. T

Once Mrs. T was stabilized, the focus shifted to rehabilitation to address the physical, cognitive, and emotional deficits caused by the stroke.

- Physical Therapy (PT):

- Addressing the left-sided hemiparesis with exercises to strengthen her muscles and improve mobility and coordination on the left side of her body.

- Gait training was incorporated to help her regain independent walking.

- Occupational Therapy (OT):

- Considering that Mrs. T exhibited left-sided neglect, OT focused on improving her ability to perform daily living activities (e.g., dressing, bathing, toileting, eating) while compensating for her lack of spatial awareness.

- Tools and exercises were given on the use of adaptive equipment to help with personal hygiene and feeding herself.

- Speech Therapy (ST):

- Although her speech was slurred, Mrs. T did not have significant aphasia, as his stroke was right-sided. However, she received therapy and found this improved the clarity of her speech and mild cognitive-communication deficits.

- Nutrition Consult

Long-Term Care and Stroke Prevention

- Antihypertensive medication to maintain his blood pressure within normal range.

- Statin therapy for cholesterol management.

- Antiplatelet therapy to prevent clot formation.

- Diabetes management through insulin and lifestyle changes, including diet and exercise.

- Lifestyle modifications, such as smoking cessation, a heart-healthy diet, and regular physical activity, were emphasized during follow-up consultations.

Activity: Stroke Obstacle Course (A Simple Day)

This activity encourages reflection and empathy for those impacted by strokes. This is a simple daily routine at home. This does not account for days that involve transportation to medical appointments and therapy, social activities, or other community involvement.

|

“A Day in the Life of a Client Recovering from Stroke” and Possible Obstacles **Obstacles are italicized |

||

| Time | Activities | Obstacles Accompanying Stroke |

| 9:00 AM |

Wake-Up and Morning Routine

|

Depression or mood changes can make waking up difficult or exhausting. There may also be stiffness and pain to the unaffected arm due to lifting the affected arm and doing all needed movements solely. Difficulty standing, walking, grasping objects, lifting extremities, and balancing. Buttons and zippers can take an absorbent amount of time to work. |

| 10:00 AM |

|

Difficulty with grasping medication tablets, difficulty or impaired swallowing, memory deficits. |

|

10:30 AM – 12:30 PM |

|

Impaired memory, problem-solving skills, and attention makes it difficult to follow instructions, complete tasks, or focus on multiple steps. Even routine activities like making a meal or managing medications can become overwhelming. Difficulty grasping objects, lifting extremities, and decreased strength/ use of an extremity makes these task time-consuming and frustrating. Impaired executive functioning impacts activities such as planning decision-making, organization, cooking, or managing finances. Numbness and loss of sensation make it hard to manipulate objects or perform fine motor tasks. |

|

1:00 PM

|

|

Fatigue and muscle deterioration are common following strokes. |

| 3:00 PM |

|

Aphasia hinders the ability to speak, understand language, read, or write. This can make communication, social interaction, and tasks like reading or writing extremely difficult. |

| 5:00 PM |

|

It is time to eat once again, even though breakfast and lunch each took around an hour to eat. |

| 8:00 PM |

|

Sleep disturbances is common after a stroke, including difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or waking up too early. Urgency and incontinence is a major reason for disturbed sleep patterns. |

Conclusion

Throughout this course, we have explored the complexities of right and left-sided strokes, focusing on the unique symptoms and the specialized care required for each. Right-sided strokes, often associated with spatial and perceptual issues like neglect, impact the left side of the body, while left-sided strokes are closely linked to language and communication difficulties, such as aphasia, and affect the right side of the body. Knowledge of the opposite impact of motor functioning is also a critical aspect of stroke evaluation.

Recognizing the distinct signs and symptoms of each type of stroke is critical for providing timely interventions, reducing long-term complications, and developing tailored rehabilitation plans. By understanding these differences, healthcare providers can improve outcomes for stroke survivors, ensuring they receive the most effective, targeted treatment for their specific needs.

References + Disclaimer

- Baser, Y., Zarei, H., Gharin, P., Baradaran, H. R., Sarveazad, A., Roshdi Dizaji, S., & Yousefifard, M. (2024). Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale (CPSS) as a Screening Tool for Early Identification of Cerebral Large Vessel Occlusions; a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Archives of academic emergency medicine, 12(1), e38. https://doi.org/10.22037/aaem.v12i1.2242

- Dlugosch, L., Story, L., & Story, L. (2021). Applied pathophysiology for the advanced practice nurse. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Grotta, J. C., Albers, G. W., Broderick, J. P., Kasner, S. E., Lo, E. H., Sacco, R. L., Wong, L. K., & Day, A. L. (2022). Stroke: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management (Seventh edition). Elsevier.

- Hankey, G. J. (Ed.). (2019). Warlow’s stroke: practical management. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Hughes RE, Tadi P, Bollu PC. TPA therapy. (2023) In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482376/

- Kuriakose, D., & Xiao, Z. (2020). Pathophysiology and Treatment of Stroke: Present Status and Future Perspectives. International journal of molecular sciences, 21(20), 7609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21207609

- Lee, S.H. (2020). Pathophysiology of stroke: from bench to bedside. Springer.

- Martin, S. S., Aday, A. W., Almarzooq, Z. I., Anderson, C. A., Arora, P., Avery, C. L., Baker-Smith, C. M., Barone Gibbs, B., Beaton, A. Z., Boehme, A. K., Commodore-Mensah, Y., Currie, M. E., Elkind, M. S., Evenson, K. R., Generoso, G., & Heard, D. G. (2024). 2024 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: A Report of US and Global Data From the American Heart Association. Circulation: Journal of the American Heart Association., 149(8). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001209

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NIH). (2024). NIH stroke scale. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/NIH-Stroke-Scale_updatedFeb2024_508.pdf

- Platz, T. (Ed.). (2021). Clinical pathways in stroke rehabilitation : evidence-based clinical practice recommendations. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58505-1

- Tadi P, Lui F, Budd LA. Acute Stroke (Nursing) [Updated 2023 Aug 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK568693/

- Wiki Common. (n.d.). Circle of Willis [image]. Public domain release. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Circle_of_Willis_en.svg

- Zimmerman, E. E. (2023). Neurologic localization and diagnosis : differential diagnosis by complaint-based approach (M. A. Samuels, H. S. Kirshner, & K. E. Misulis, Eds.). Elsevier Inc.

- Hickey, J. V., & Strayer, A. (Eds.). (2020). The clinical practice of neurological and neurosurgical nursing (Eighth edition.). Wolters Kluwer.

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate