Course

Scabies: Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Course Highlights

- Upon completion of this course, learners will have a clear understanding of what scabies are.

- Learners will review clinical aspects of scabies infections as a part of this course.

- At the end of this course, learners will improve their knowledge regarding treatment and prevention of scabies infections.

- Learners will read about current research and topics for future research that could improve the diagnosis and treatment of scabies and prevent the spread of this disease.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 3

Course By:

Mary Harris

MSN, RN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Parasitic scabies infections are a common global occurrence, affecting over four million individuals worldwide each year. Even in developed, industrial nations, scabies outbreaks can occur in hospitals, nursing homes, dorms, and communities. Scabies can be quickly spread before an individual experiences symptoms. Therefore, nurses must understand precisely what scabies are, possess knowledge of the clinical elements of a scabies infection, be familiar with treatment methods, and learn about current and future research regarding this global issue.

Introduction

Scabies are one of the most common skin diseases, affecting over 200 million people in the world at any given time and more than 400 million people each year. This parasitic infection causes intense itching, leading to bacterial infections and other complications. The speed of transmission and recurrence of scabies make treatment challenging in many areas. In the United States, scabies infestations are sporadic. However, they can still spread quickly (1), and nurses should be familiar with the disease to help reduce the spread and impact of the skin disease in the community.

Definition

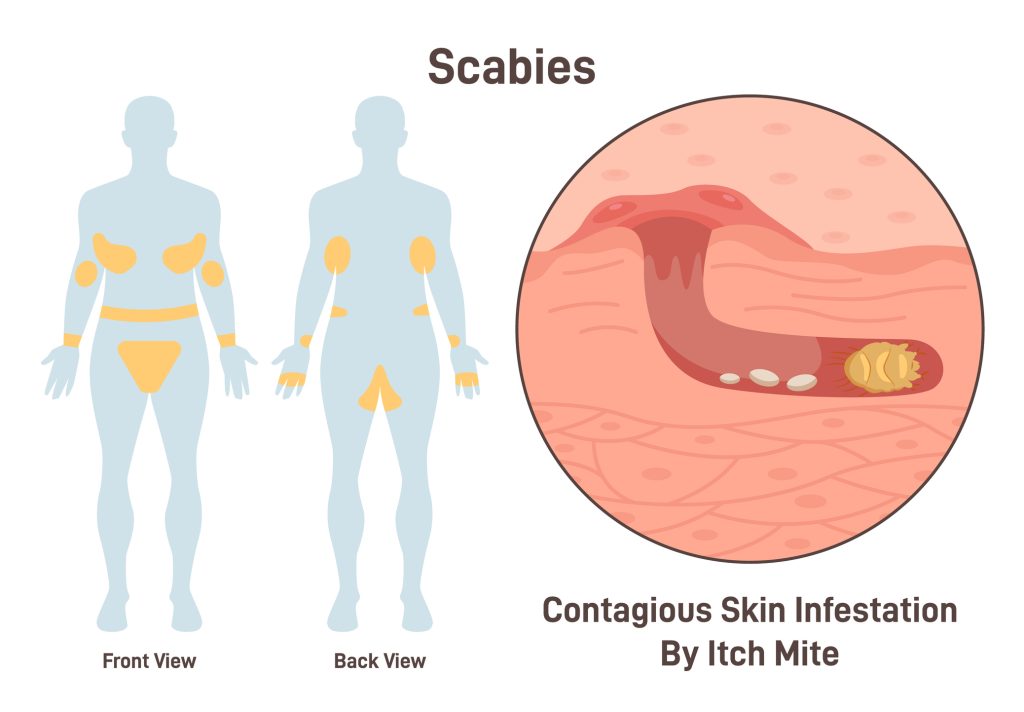

Scabies is a common parasitic infection directly caused by the human itch mite sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis (2) that produces intense itching on the skin, particularly at night. This arthropod is 0.25-0.45mm long as a fully grown adult and burrows into the upper layer of the skin, as deep as the stratum corneum. When the mites burrow, they create small tunnels under the skin that appear as tiny grey or flesh-colored lines on the skin.

These burrow tracts can be a centimeter or longer. As the female mite burrows, it lays eggs and can reproduce for 1-2 months until the end of its lifecycle. When the eggs hatch, the larvae move to the skin’s surface, creating small, temporary burrows to mature within. This activity creates a pimple-like rash (3). The presence of mite proteins and feces in the burrows contributes to the characteristic intense itchiness of the disease. Scabies are incredibly contagious and spread quickly between family members. They can also spread through fomites, like towels or bedding (1)

There are various scabies, with the classic form being the most common. In addition to this, there is also the crusted form, formally known as Norwegian scabies, as well as nodular scabies (4), nail scabies (5), and bullous scabies (6). Crusted scabies are a severe form of scabies that are highly contagious. Hyperkeratotic plaques, which are thick, rough patches of skin caused by a buildup of keratin, can develop on the skin. These plaques may be fissured and have erythema.

Patients with crusted scabies may not have the characteristic pimple-like rash, or the itchiness associated with the disease may be mild or absent (7). While individuals with classic presentations of scabies are typically infected by 10-15 adult mites, those with crusted scabies may have up to two million mites and eggs present on their skin (7). Nodular scabies are a less common condition that typically affects the genital area but can also affect the axillae, trunk (in infants), and groin (5).

Firm, pruritic nodules characterize nodular scabies and are more common in men who have sex with men (8). Bullous scabies are rare and usually affect older patients. It is characterized by large, blister-like lesions that are highly pruritic. There may or may not be signs of classic scabies in cases of bullous scabies. Nail scabies are also rare and are typically found in immunocompromised adults with crusted scabies. Very rarely, only the patient’s nails may be affected. This type of scabies can result from scratching at scabies on the skin, potentially leading to discoloration and thickening of the nails (5).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Why do you think scabies is so prevalent globally?

- How are scabies spread through fomites?

- What are the different forms of scabies?

- Why are crusted scabies enormously more contagious than classic scabies?

Assessment

Scabies are frequently misdiagnosed, with one study discovering that 45% of scabies diagnoses were initially missed. This is because, until recently, no consistent method was used for diagnosing scabies. In 2018, an international consensus for the diagnostic criteria of scabies was established.

Participating researchers decided that a case of confirmed scabies can be diagnosed if mites, eggs, or feces are observed using light microscopy of skin samples, visualization on the skin using a high-powered imaging device, or visualization through dermoscopy. Clinical scabies may be diagnosed if there are scabies burrows, typical lesions on male genitalia, or if there are typical lesions present elsewhere on the body with at least two history features.

History features include itchiness or close contact with a person who has experienced itchiness or has typical scabies lesions in the usual distribution pattern. Suspected scabies may be diagnosed if the patient has typical lesions and one history feature or atypical lesions in an atypical distribution with two history features (9).

Scabies are typically diagnosed through visualization and patient history assessment (10). During the physical evaluation, the provider may observe white snake-like lines on the skin resulting from burrowing by the mites. These signs of burrowing are typically located in the groin, axillae, umbilicus, between fingers, around the wrists, and in any other areas of skin folds. Red bumps may appear on the skin due to the body’s reaction to mites, their eggs, and their feces. These bumps are typically highly pruritic. The provider may also observe impetigo, a common complication of scabies. Some patients may not have prominent exam findings, which makes a detailed history important. Scabies should always be considered as a diagnosis when multiple family members report intense skin itching (10).

While visualization of the classic rash is the most typical method for diagnosing scabies, other techniques may be used. The provider may visualize mites while examining skin scrapings; however, the likelihood of a false negative is high since there are typically only 10 to 15 mites on an infected individual. Noninvasive videodermatoscopy uses a video camera that utilizes optic fibers to create 1000x magnification. This method can help to identify mites, burrows, eggs, and larvae, but it is not commonly used in the United States (10).

This method may be helpful, though, when the provider has difficulty differentiating between burrows and excoriation of the skin (9). Dermoscopy is more commonly used and utilizes a handheld device capable of 10x magnification. Burrows can usually be observed using this method, though it may be more difficult on darker skin tones or areas of dense hair (10). Sometimes, providers will describe a “delta wing jet” design, which includes a dark brown triangular spot followed by a white squiggly line.

The dark brown spot is the body of the scabies mite, and the white squiggly line is the burrow. Eggs within burrows can also be identified. In crusted scabies, multiple burrows will be observed through dermoscopy, and some areas will have a hyperkeratotic appearance (5). The benefit of dermoscopy is that it is a noninvasive method but is as sensitive as skin scraping when assessing for scabies (9). A skin biopsy may be used to confirm a diagnosis of scabies (10).

Other methods have been used to diagnose scabies, though follow-up with dermoscopy is recommended. A Wood’s lamp, which emits a kind of blacklight, can illuminate the tunnels created by scabies mites with a bright white contrasting light. This method may guide dermoscopy or evaluate scabies treatment effectiveness (11). A burrow ink test has been used to assess tunnels made by scabies mites, which could help guide diagnostic procedures but does not rule out the presence of scabies. In this test, one of the pruritic papules is covered with a purple skin marker.

The ink is then wiped away, revealing a dark purple meandering line representing the tunnel, while the skin surrounding it remains a lighter shade of purple (12). The presence of the dark, curvy line indicates a positive test. However, a complete diagnosis cannot be made using this method because the test method will also identify old, non-active lesions (5). The adhesive tape test involves placing the adhesive tape on top of skin lesions. The tape is then pulled from the skin and immediately put on a slide, which can be observed with a microscope. This examination may reveal the presence of mites on the skin (5).

Reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) uses a reflected laser beam to survey the layers of skin to evaluate for mites, eggs, larvae, and their feces. This method can be used to observe active burrowing. The burrows created appear in a linear pattern, while the surrounding skin cells display a honeycomb pattern. This method is not commonly used because it is time-consuming and costly (5), but it is accurate in diagnosing classical and crusted scabies. It may have some benefits for use in research settings (9).

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is another noninvasive technique for diagnosing scabies (5). It is similar to ultrasound but produces higher-resolution cross-section images (9). Reflected near-infrared beams observe the skin and reveal mites, eggs, feces, and burrows. OCT can observe the skin vertically and horizontally, making it a time-efficient technique. It can also be used to study treatment progress (5). Like RCM, this method depends on specialized technology, so it may not be commonly used in clinical settings (9).

Serology tests have been studied to evaluate their usefulness in diagnosing scabies, but none have been implemented due to a lack of consistent and persuasive evidence. Antibodies of scabies can be detected using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). High IgE levels have also been documented for patients with scabies. An enzyme found in the mouths of scabies, tyrosine kinase, has also been studied as an early diagnostic tool. DNA testing of skin swabs and biopsies can be used to diagnose scabies (5).

Skin scraping is an invasive technique used to diagnose scabies. Mineral oil is applied to the skin at the suspected lesion sites. The skin is then gently scraped using a sterile blade. A microscope is used to observe the skin scraping for signs of scabies activity. This method is time-consuming and not well-tolerated by young children. Due to the scraping activity on the skin, it can also lead to infections (5).

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay is an accurate test for diagnosing scabies. Still, it is not commonly used because it hasn’t been studied in various populations or for different scabies. It also requires specialized equipment. This test is considered more valuable as a screening tool during scabies outbreaks (5).

The most accurate diagnostic test for scabies is skin biopsy (5). However, it is not commonly used because it is not often needed for a precise diagnosis. It may be used for patients with an atypical presentation of scabies. The biopsy doesn’t usually result in the visualization of a mite but may reveal the burrow and other evidence of the presence of a mite. Neutrophils and eosinophils will likely be observed if mites exist (10).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Why do you think scabies are often initially misdiagnosed?

- How can standardized criteria for diagnosing scabies improve outcomes?

- Why are history features often necessary for a scabies diagnosis?

- Why is rash visualization typically used to suggest a diagnosis?

- What are some diagnostic tools when assessing for scabies?

- If some diagnostic methods are more accurate than dermoscopy, why don’t providers typically use them?

- Why are noninvasive diagnostic methods preferred over invasive methods?

Epidemiology

Scabies are easily spread from person to person through close contact and, though rarely, through objects that have been in close contact with an individual infected with scabies. Classical scabies are not typically spread through casual contact, like a handshake or quick hug (13). People with more mites on their skin will spread scabies more easily. Since crusted scabies involve significantly more mites than classical scabies, it is more easily transmitted. Symptoms may be delayed after infection, so an individual could spread scabies before knowing they are infected (1). Infants, young children, geriatric adults, and immunocompromised individuals are at increased risk for a scabies infestation (14).

Scabies are more easily spread in crowded environments; therefore, risk factors are often based on the setting. Scabies outbreaks are found in nursing homes, extended care facilities, jails, prisons, and childcare facilities (2) In these settings, scabies outbreaks can be costly and challenging to control (1). Scabies infections are estimated to affect more than 400 million people worldwide each year (1). However, this number is believed to be an underestimation due to a lack of utilization of standardized diagnostic criteria and little point-of-care testing (14).

It is found in every country but more commonly occurs in resource-poor tropical areas (1), including Africa, Southeast Asia, Australia, and South America (10) Recurrence is also high in these areas (1). Within geographical regions, there is variation in prevalence. For example, scabies are more commonly seen in rural areas of tropical northern Australia. The prevalence rate among Indigenous Australian Communities is 50%, while the national rate for Australia is only 0.2-4% (14). Even in countries where scabies are pretty prevalent, like Ghana, with a rate of more than 70%, or in Indonesian schools, which have a prevalence rate of more than 75%, it is not always treated as a health priority (14).

In these settings, scabies are more commonly seen in pediatric and young adult populations, with a prevalence rate of 5-50%. This correlates with prevalence rates of poverty, poor nutritional status, homelessness, and inadequate hygiene. The prevalence of scabies in these regions is associated with high morbidity due to complications and secondary infections (10). Immunosuppressed individuals are more likely to be infected with scabies (9).

Scabies outbreaks do occur in more industrialized regions (10). Even in more affluent countries, the prevalence among different populations varies. Socioeconomic disparities and lack of access to healthcare impact this. When diagnosis and treatment of scabies is delayed, it is more rapidly spread within a community. Outbreaks can occur in overcrowded communities in countries with lower infection rates, such as those with large populations of refugees (14).

Widespread outbreaks can occur quickly in institutionalized settings, like hospitals, nursing homes, prisons, dormitories, and shelters. In some of these settings, patients are more likely to be immunosuppressed. Delayed diagnoses may contribute to these outbreaks if the medical staff are unfamiliar with scabies or if there are atypical presentations due to inappropriate treatment, like the use of topical corticosteroids. Diagnosis may also be delayed for patients unable or unwilling to communicate their symptoms. In these settings, there are public health guidelines to contain outbreaks when they occur (9).

Scabies are more prevalent in areas of high population concentration, and their prevalence is not dependent on racial, socioeconomic, or age factors, though these factors may correlate with scabies diagnoses. Scabies are more commonly seen in young children and older adults, not because they are inherently at higher risk but because they are more likely to spend a significant amount of time in an overcrowded environment, like a school or nursing home. Socioeconomic factors impact scabies prevalence, but this is due to a lack of resources, which can lead to overcrowding and less-than-ideal hygiene conditions. Malnutrition also contributes to a higher risk of contracting scabies (14).

Scabies outbreaks can also occur in the presence of natural disasters, such as drought, earthquakes, and floods (9). Displaced populations living in overcrowded, poor conditions are more likely to experience a scabies outbreak (14). Some scientists suggest that changes in the global climate may contribute to the prevalence and distribution of scabies mites (14).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Why are classical scabies not typically spread through casual contact, like a handshake or quick hug?

- How do scabies spread in crowded environments?

- How does the delay in the onset of symptoms during a primary scabies infection contribute to the spread of scabies?

- Why is the reported number of cases of scabies likely underestimated?

- What type of climate are scabies outbreaks more common?

- Where do scabies outbreaks typically occur in more developed areas?

- What social factors could delay a diagnosis of scabies?

- Why is scabies more common in young children and older adults?

- How do socioeconomic factors increase the risk for scabies infections?

Pathophysiology

Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis (S. scabiei) is a microscopic parasitic mite that lives its entire lifecycle in the human epidermis (9). It has a tortoise-shaped body with a head-like structure and an abdominal structure with four pairs of legs (6). It can burrow into the skin using mouthparts and secretions (14). When the mite begins to burrow, its saliva proteins help break through the skin’s uppermost layers. Its front set of legs creates a tortoise-like motion to advance, creating a tunnel. The mite ingests the intracellular fluid of the host’s skin cells in the stratum corneum, providing it with enough water to survive (6). There are multiple variations of Sarcoptes scabiei, so the same scabies that can cause mange in dogs do not typically infect humans (6).

Adult males mate with the female mite by penetrating the molting pouch, a shallow burrow under the skin’s surface. Mating occurs once, and the female is fertile for the rest of her lifespan. Once pregnant, the female leaves the molting pouch and seeks a location to create a burrow (3). Adult female mites burrow into the skin, though not deeper than the stratum corneum, where they can lay 2-3 eggs daily. After 2-4 days, the eggs hatch into larvae, which travel back through the burrow made by the adult female to the surface of the skin. These larvae become nymphs within 3-4 days and, 3-7 days later, are sexually mature adults. These mites are capable of living 4-6 weeks (9). Transmission typically occurs when an impregnated female mite is transferred through skin-to-skin contact and burrows into the new host’s skin (3). Papules usually found at the burrow site may appear 2-5 weeks after infestation. Mites tend to burrow through more thin layers of skin. Therefore, the papules are typically found in areas like the spaces between the fingers, wrists, areolae, naval region, and the shaft of the penis (1).

When the impregnated adult female mite burrows into the skin, opportunistic microorganisms, like bacteria, can proliferate. Bacteria are present in mites’ intestinal systems and are spread to humans through mite feces within burrows (14) Opportunistic bacterial infections secondary to the scabies infection typically include Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus pyogenes. These bacteria commonly infect scabies lesions, leading to impetigo, a contagious skin infection that can lead to abscesses in deeper tissues, cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis, bacteremia, and sepsis. Bacterial infections due to scabies can also contribute to glomerulonephritis, chronic kidney disease, or rheumatic heart disease. However, the number of incidences directly due to scabies is unknown due to multiple contributing factors (14).

The human host develops an immune system reaction to the proteins in the mite feces and the opportunistic bacteria. The host immune response includes IgM, IgA, IgG, eosinophils, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and pro-inflammatory cytokines (14). The immune response is activated first by keratinocytes, dendritic cells, and Langerhans cells (6). The immune response may take a few weeks to become active during the primary infestation. However, in subsequent infections, the immune response is much quicker. The exact mechanism that causes the intense itchiness associated with scabies is unknown, but it may be due to the feces and mite proteins in the burrows (14).

When the mite’s feces and proteins reach the dermis, they stimulate fibroblasts, endothelial cells of the microvasculature, and immunological effector cells. Immunological effector cells include Langerhans, macrophages, mast cells, and lymphocytes. Once these cells pick up and process the antigens, they are transported to the lymphatic tissue, which activates B- and T-lymphocytes. This triggers an adaptive immune response with specific antibodies, though these antibodies do not seem to protect the host from future infections.

The immune response varies between cases of classical scabies and crusted scabies. In crusted scabies, mast cells and basophils are found in the dermis. In classical scabies, there is a more protective local immune response. Crusted scabies typically trigger some non-protective reactions at the site of inflammation, which stimulates the endothelial cells, keratinocytes, and fibroblasts. These cells produce inflammatory cytokines, which are small proteins that affect the growth and activity of other cells. Crusted scabies trigger a stronger antibody-mediated immune response than classical scabies (6).

The intense itching associated with scabies results from the mites’ actions and the human host’s immune response. The intense itching elicits scratching, which can alter the skin integrity and create more opportunities for possible secondary bacterial infections (14). This itchiness is a result of the human immune response. The antigens released by live and dead mites can enter the dermis, triggering the immune and inflammatory response. The presence of T lymphocytes causes the lesion development. The cellular response patterns in crusted scabies are similar to those in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis (6). Itching associated with scabies can continue after treatment because the dead mites trigger an antibody response for a few weeks, even after treatment (6).

The host’s immune system is ineffective at combating the scabies mite infestation in crusted scabies. Therefore, those who are immunocompromised are at higher risk for crusted scabies. This reaction produces thickening of the epidermis through hyperkeratosis caused by rapid stratum corneum growth (14). Thickening is often found on the soles, palms, ears, and extensor surfaces of the elbows but can be found on any skin surface (5).

Evidence suggests the hyperkeratosis reaction may be due to a dysregulated cellular immune response (14). In the presence of crusted scabies, sebaceous glands, and hair follicles are typically hyperplastic, blocked, and inflamed. In animal studies, crusted scabies, immune systems, and inflammatory-related changes were found in the hepatic, renal, cardiac, and splenic tissues. However, other studies did not see changes in these tissues. This may depend on the severity of the infestation. Studies have also found lymphoid hyperplasia, congestion, and amyloid deposits in those with crusted scabies (6).

Diagnoses of crusted scabies are divided into three grades based on distribution, severity of crusting, past episodes, and the overall skin condition. Four categories are scored on a scale of 1-3 based on symptoms to grade crusted scabies. The total score determines the grade and guides treatment.

Crusted Scabies Scoring

- Distribution and extent of crusting

- Wrists, web spaces, feet only, less than 10% of total body surface area (TBSA)

- Areas listed in #1, plus forearms, lower legs, buttocks, trunk, or 10-30% of TBSA

- Areas listed in #1 and #2, plus scalp or greater than 30% of TBSA

- Crusted/shedding

- Mild crusting (less than 5mm depth of crust) with minimal skin shedding

- Moderate crusting (5-10mm depth of crust), moderate skin shedding

- Severe crusting (more significant than 10mm depth of crust), profuse skin shedding

- Past episodes

- Not previously infected

- Has had 1-3 prior hospitalizations for crusted scabies, or the patient has depigmentation of elbows or knees.

- Has had four or more previous hospitalizations for crusted scabies or depigmentation included in #2, plus legs and back or residual skin thickening and ichthyosis

- Skin condition

- No cracking or pyoderma

- Multiple pustules and/or weeping sore and/or superficial skin cracking

- Deep skin cracking with bleeding, widespread purulent exudates

One level is selected for each category, and the corresponding number is circled. Then, each category’s numbers are added to form the total score. A score of 4-6 is categorized as grade 1, 7-9 is categorized as grade 2, and 10-12 is categorized as grade 3 (14).

Nail scabies are thought to originate from scratching infestation sites. Evidence suggests that while scratching, mites are transmitted to under the fingernails. Hyperkeratosis under the nail lifts the nail and further compromises the protective barrier of the fingernail. This process can cause the nail to separate from the nail bed or for the nails to become brittle and split (5).

Nodular scabies is generally thought to result from hypersensitivity. Severe skin reactions, similar to eczema, and incredibly itchy nodules, especially on the male genitalia and breasts, can continue for months after treatment. In cases of nodular scabies, dense areas of inflammation and the associated immune cells create lesions. Nodular scabies may occur during an active infestation or after treatment (6).

The mechanisms associated with bullous scabies are still under investigation. It is suggested that bullous scabies may result from secondary infections of lesions with Staphylococcus aureus. Bullous scabies present similarly to impetigo, but through microscopy, mites, eggs, and mite feces are seen (6).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How do scabies mites burrow through the skin?

- How are scabies spread from one host to another?

- How are opportunistic bacteria related to a scabies infection?

- What causes the intense itching typically associated with a scabies infection?

- Why does itching continue for weeks after scabies treatment?

- Why do you think crusted scabies have a multi-systemic effect on the human body versus the more localized reaction present with classic scabies?

- How does having a grading system for crusted scabies help to determine appropriate treatment?

- What do researchers think causes nail scabies?

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms of scabies typically begin 4-6 weeks after infestation due to the time needed to elicit an immune response. The symptoms may appear in subsequent infections within a few days (1). The hallmark symptom of scabies is extreme itchiness. Over 90% of individuals experiencing a scabies infection report intense itching. Patients report that this itching worsens at night and may interrupt their sleep (14). Other symptoms may include erythematous papules where the burrow sites are located. Burrows and papules are often found on the fingers, wrists, arms, legs, and waist (1).

Burrows may not be able to be visualized in cases of classic scabies (9). They can also be found in the armpits, in the inner elbows, on the chest, around the nipples, around the genitals, in the groin, and on the buttocks (15). The rash present with scabies may spread slowly over several months. There may be areas of the skin that appear infected (4). Scratching can lead to encrustation and possible impetigo due to secondary infections. Since scabies spread quickly, family members in the same household may also report itchiness (10).

Atypical symptoms that differ from those found in classical scabies generally characterize other scabies infestations (9). Crusted scabies present with specific symptoms, including dry, eczema-like skin areas, but they often do not itch (1). Crusted scabies symptoms are generally widespread and may be found on the head and neck, whereas this is typically not found in cases of classical scabies. People experiencing crusted scabies may also present with lymphadenopathy (9).

Typical burrows and papules may not be seen on those with nodular scabies; instead, they will present with pruritic nodules, often found in the axillae, groin, or male genitalia. Individuals experiencing bullous scabies will have lesions in the same areas as classical scabies. Still, instead of the typical presentation, they have fluid-filled blisters, which may be flaccid or tense and more extensive than 5mm. They may or may not itch (9).

Symptoms of scabies infestation may vary for individuals in different populations. Small children infected with scabies may have a more extensive, widespread rash, including their palms, soles, ankles, and scalp (1). They may be more irritable and feed poorly (9). Itchiness at night may keep children from sleeping well, which may cause them to be tired or fussy (4).

Older adults may not have a strong inflammatory response, though itching is still typically present. These vague symptoms may also be present in immunocompromised individuals with scabies (9). Mild itchiness may be mistaken for another skin condition and delay the necessary treatment, which could cause complications (14). Individuals with limited mobility may present with lesions on their back (9).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Why do you think symptoms of a primary infection of scabies are delayed compared to reinfestation symptoms?

- What is the hallmark symptom of scabies infection?

- Why are scabies rashes more commonly found in some regions of the body?

- Why may the rash associated with scabies spread slowly?

- What are some atypical symptoms of scabies?

- What are the specific symptoms of crusted scabies?

- What are some reasons the symptoms of a scabies infection could vary among different populations?

- Why do you think infants with scabies often experience sleep and feeding difficulties?

- How does reduced itchiness for some patients with scabies infections contribute to misdiagnosis?

Etiology

The symptoms of a scabies infestation are directly associated with the burrowing of scabies mites in the skin of humans (2). Evidence of scabies infestations, though not named then, has been found in Biblical texts and in Aristotle’s treatise De Historia Animalium, where he describes the parasite as “lice in the flesh.” It is thought that the condition was first called “scabies” in 25 AD by Roman author Aulus Cornelius Celsus.

In medieval times, Dante, in his Divine Comedy, describes the symptoms of scabies. In the 16th century, Dr. Thomas Moffett established the pathogenic connection between the scabies mites and differentiated them from lice. Drawings of scabies mites are found from the 17th century. Various other scientists over the centuries have studied scabies, and novel discoveries continue to be made. Until recently, a diagnosis of scabies was made by examination of skin scrapings, but dermoscopy, developed in the first decade of this century, now provides a noninvasive, though accurate, diagnostic tool. The etiology of scabies infections may be well-established, but research regarding accurate diagnostic methods and effective treatments continues (16).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Why do you think ancient writers may have called scabies “lice of the flesh?”

- What progress has been made in scabies diagnoses?

- Why do you think scientists continue to make discoveries about scabies and treatments even though it has been a known disease for thousands of years?

Treatment

All types of scabies can be treated with topical creams. In severe cases, like crusted scabies, oral medication may also be used (1). The medicines used to treat scabies are called “scabicides” and are only available with a prescription (17). Evidence suggests that when treatment medications are used as directed, treatment efficacy is comparable among the medicines used. Adverse reactions to the treatments for scabies are not common (10). When a topical cream is used, it is applied to the whole body to ensure complete eradication of scabies (1). The application time of these creams may vary for children based on their weight (18).

Topical Permethrin 5% cream is considered the frontline treatment option for scabies and was approved by the FDA in 1989 (9). This medication is a synthetic extract from the chrysanthemum flower (17). This cream is applied once a week for two consecutive weeks for two total treatments. This is to ensure any newly hatched mites are also killed. Occasionally, this treatment results in scabies resistance. There may also be issues with patient compliance and rare allergic reactions (10) Permethrin 5% cream can be used for adults, pregnant women, and children 2 months and older (15). Permethrin 5% cream works by inhibiting sodium channels and causes neurotoxicity, paralysis, and death in the mites it comes in contact with. This cream is left on overnight and then rinsed off. The process is typically repeated in 7-14 days. Side effects may include burning, itchy skin, and erythema (9).

The FDA does not approve topical sulfur 2-10% ointment or cream, but it is sometimes used to treat scabies when other treatments are unavailable. Sulfur is keratolytic, meaning it can break down the body of the mites directly (9). The sulfur creams prescribed are typically applied and left on the skin overnight, then rinsed off in the morning. The patient follows this regimen for five nights (15). Side effects include a foul odor and burning (9). Sulfur 2-10% cream treatments are safe for pregnant women and children under two months old, unlike some of the other treatment options (15).

Topical Benzyl benzoate 10-25% may be used to treat scabies when permethrin 5% is unavailable, though it is unavailable in the United States or Canada. This cream works by inhibiting the respiratory system of the mite, causing them to asphyxiate. It is applied for 24 hours, rinsed off, and the process may be repeated in 7-14 days. Side effects may include burning and eczematous eruptions. This medication is safe for infants but is typically diluted for children to minimize irritation (9). Topical medicines like crotamiton 10% and malathion 0.5% may be used. Still, they are less effective than other treatment options, and their use is not as supported in the literature. Malathion is considered to be carcinogenic to humans. As a result, there is little data to support its use for children, and it is contraindicated to use for infants (9). Spinosad topical suspension 0.9% is FDA-approved to treat scabies, but data to support its use is limited to two randomized control trials (17).

Topical Lindane 1% lotion was approved for treating scabies in 1981. It is a central nervous system stimulant and causes paralysis, seizures, and death of the mite. It is applied for eight hours and then rinsed off. Side effects may include seizures, aplastic anemia, and eczematous eruptions. It is contraindicated for use in infants, pregnancy, breastfeeding, patients with a history of seizures, crusted scabies, and any skin condition that increases absorption. Treatment resistance has been reported with this medication, and it is banned in several countries due to its risk of neurotoxicity and classification as a carcinogen to humans (9).

Oral treatment may include ivermectin (Stromectol) (1). This treatment for scabies is not approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration but is commonly used for this purpose. A 200 mg/kg/kg/should be taken with food to increase bioavailability (17). This treatment is used for patients ten years and older; only one dose is necessary. After two weeks, if symptoms of scabies continue, another dose may be given. Oral ivermectin is considered safe and has few side effects. Patients also tend to comply more with oral ivermectin treatment than topical cream treatments (10). Evidence suggests that oral ivermectin has similar efficacy in treating scabies as topical permethrin (17).

It is important to note that treatments for scabies do not kill the eggs that have already been laid in the skin. Treatment should be repeated so that newly hatched mites are also killed. Since symptoms of an infestation may not be apparent for a few weeks, all household members should be treated, regardless of their symptom status (1). When an outbreak occurs within a very crowded community, the community may be treated as a cluster to eradicate the epidemic (18).

Cases of crusted scabies require more intensive treatment using both topical and oral medications (1). There is no specific clinical guideline for prescribing oral ivermectin for crusted scabies, as it is not FDA-approved for this purpose. However, some methods used include a series of three treatments given on days 1, 2, and 8, a series of five treatments given on days 1, 2, 8, 9, and 15, or a seven-dose series given on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, 22, and 29. The treatment method used may depend on the severity of the case (17).

In cases where the patient has had more than one episode of crusted scabies within the last 12 months, a treatment protocol known as boosted grade 3 may be used, which involves ten doses of oral ivermectin, with doses given on specific days over four weeks (14). In addition to the ivermectin doses, a daily application of Permethrin 5% cream every three days for 1-2 weeks may be recommended for cases of crusted scabies (17). A topical keratolytic cream, such as urea/lactic acid or salicylic acid (14). may also be prescribed to reduce the skin’s crusting and aid the permethrin in its ability to penetrate the crusted areas of the skin. Typically, this cream is applied on the days the permethrin cream is not being used (17).

Antibiotics will be used to treat the infection if there has been a secondary infection due to a scabies infestation (1). Topical antibiotic creams, like mupirocin or fusidic acid, are not recommended, as the treatment needs to target group A streptococcus and S. aureus, which may include methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Oral trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole (Cotrimoxazole) or intramuscular benzathine penicillin G are used in tropical regions where scabies are commonly found. Pristinamycin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, or cephalexin are used in other areas. Antihistamines may be used for severe secondary bacterial infections, but this is due to the sedative properties of these medications that can reduce scratching rather than their anti-pruritic mechanisms (18).

Drug tolerance is an increasing problem as healthcare providers seek to treat scabies. Scabies tolerance of treatment with permethrin 5% is increasing in some European countries, including Germany, Austria, and Italy, with failure rates as high as 70%. The United Kingdom also reports an increase in treatment failures. Identifying direct causes of treatment failure is difficult, as multiple contributing factors exist.

There may be inadequate application of the treatment cream, non-compliance with treatment, reinfection due to untreated contacts, or failure to treat the environment using hygiene practices, like washing bedding in hot water. Some of the documented treatment resistance may be categorized as pseudo-resistance, as the resistance is not due to the failure of the prescribed treatment plan. There is evidence of genetic mutations within the mites contributing to drug resistance, but the statistical prevalence of treatment failure cannot be accurately determined without further research. Oral ivermectin treatment resistance has been documented in cases of crusted scabies but is very rare (14).

In addition to medication treatment, further steps must be taken to prevent the spread of scabies and lower the risk of reinfestation. Anyone who has had close contact with the patient within the previous two months shared a bed or used the same clothing or towels should be treated. Bedding, clothing, and towels should be washed with hot water and dried at a high temperature.

The temperature necessary to kill the mites and eggs is 50°C or 122°F for at least ten minutes. If an item is dry-clean and cannot be washed using usual methods, it can be sealed in a plastic bag for 48-72 hours. Skin-to-skin contact should be avoided until treatment is completed (2). The home of the infected individual should be thoroughly cleaned, including vacuuming furniture, carpets, and floors. This is especially necessary for patients treated for crusted scabies (15). Scabies mites are typically unable to survive more than 2-3 days when away from a human host (2).

Patients should expect the itchiness to worsen for 1-2 weeks after treatment starts but then resolve (1). Treatment failure and the recurrence of infection are common, especially if the necessary close contacts are not effectively treated. Treatment can also fail if bedding and clothes are not adequately cleaned during the treatment period. When treatment of crusted scabies fails, it is often due to ivermectin-resistant mites. In this case, moxidectin is recommended for treatment (10).

Mass drug administration (MDA) is used as a treatment strategy in areas where the prevalence of scabies is greater than 10%. It is recommended that 3-5 rounds of MDA be administered. The guidelines state that MDA is unnecessary when the prevalence is lower than 2%. Current alternatives to MDA include screening and treatment, which is resource-intensive and less effective than traditional MDA.

The treatment regimen commonly recommended for MDA for scabies is two doses of oral ivermectin given 7-14 days apart. When possible, treatment should be directly observed. Topical treatment is recommended for those not eligible to take oral ivermectin. Local factors need to be considered when designing a plan for MDA. Public health workers should consider the availability and affordability of treatment. Treatment needs to be accessible to the community (19).

There are quality-of-life implications related to scabies infestations. The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) is a questionnaire used to determine the effect of dermatological conditions on the quality of an individual’s life. While not a perfect tool for scabies diagnoses, some studies report that the DLQI does identify a mild to moderate effect on quality of life. Other studies report a substantial effect of scabies on quality of life. A primary issue that impacts quality of life includes sleep disturbances due to increased itching at night, which affects work efficiency and school absenteeism.

Patients may also feel embarrassed, with 45.5-83.3% of individuals with scabies reporting embarrassment (14). Since scabies are associated by many as being a mark of poverty, overcrowding, and poor hygiene, community misperceptions may contribute to how a patient feels about their diagnosis (6). People may feel stigmatized and isolated due to the rapid transmission of scabies. The diagnosis of scabies has also been associated with increased rates of depression and anxiety. Personal relationships and participation in sports, activities, and school events are reported as being the least affected. Secondary bacterial infections can impact the quality of life (14). The costs of treatment, school absenteeism, and missed workdays may create a significant financial burden for low-income households (6).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Why do you think a topical cream is the first-line treatment for classic scabies?

- How does compliance with all instructions for topical cream application affect scabies infestation treatment outcomes?

- How is oral ivermectin used to treat scabies?

- Why is an oral and topical treatment method typically used for cases of crusted scabies?

- What is one benefit of multiple treatment options for scabies infestation?

- Why do current topical scabies treatments need to be repeated?

- How are secondary bacterial infections treated?

- How does drug tolerance affect scabies infestations?

- What are the steps to prevent reinfestation?

- Why is it essential to treat close contacts, even if they are asymptomatic?

- Why is mass drug administration a critical element of scabies treatment in some regions?

- How does a scabies infestation affect a patient’s quality of life?

Self-management

Self-management guidelines for treating scabies center around preventing reinfection or further spread of the condition. This includes the hygienic treatment guidelines used to treat scabies conditions, such as washing all bedding and ensuring the treatment of all close contacts. Medication compliance is imperative (4). In some settings, like hospitals or nursing homes, isolation may be necessary to prevent the spread of scabies (10). Nurses can be influential in treating and limiting the spread of scabies through patient education and expressing the importance of treatment compliance.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is the focus of self-management for scabies infections?

- Why do you think isolation may be necessary to prevent the spread of scabies in some settings?

- What can nurses teach patients about reinfestation prevention?

Research

2017 The World Health Organization (WHO) categorized scabies and other similar ectoparasites as Neglected Tropical Diseases. Based on this, they have established global goals to be reached by 2030. The goals are for countries to incorporate scabies management in their universal health coverage package and for countries to conduct mass drug administration interventions in endemic areas, which are areas with a disease prevalence of greater than 10%. The WHO continues to work with its member states to develop strategies for treating and controlling scabies. Current research from the WHO also focuses on the effectiveness of single-dose MDA (1).

There is ongoing research to develop new and improved methods for preventing and treating scabies. New medications capable of killing scabies eggs are being trialed in porcine subjects. Two preclinical trials have found a single dose of moxidectin to be more effective in treating scabies than ivermectin, and research on this new medication continues. Fluralaner, which is used to treat scabies infections in animals, is also being explored as an option for treating scabies infections in humans (20). Tea tree oil, already known as an antimicrobial, is currently being studied for its ability to act as a scabicide. Due to the increasing incidence of drug resistance, other substances that could enhance the action of permethrin are being researched (9).

Research regarding methods to prevent and treat scabies is limited. There must be access to patients, and those who present with scabies typically only have 10-15 mites present. As a result of these difficulties, there have been animal studies conducted.

While scabies that infect animals do not infect humans, the porcine variation resembles the mites that infect humans and lead to classical and crusted scabies. Due to the genetic, physiological, and immunological similarities between pigs and humans, porcine mites are used to research potential treatment modalities for humans. This has led to the ability to research environmental decontamination and appropriate subjects for preclinical drug trials (14).

There are multiple areas related to scabies that need further research. There has been no accurate research regarding the global burden of scabies, including secondary bacterial infections. In the short term, a diagnostic tool for surveillance of scabies and associated bacterial infections should be developed. In the long term, this diagnostic tool could be used for global surveillance of scabies and monitoring prevalence, treatment failures, and development of drug resistance.

As a result of a lack of understanding of the worldwide disease burden, there is a lack of knowledge of the global cost of scabies. Control programs should be evaluated for their impact on the economic consequences of scabies and other similar diseases. Indicators to measure direct and indirect healthcare costs will need to be developed based on research and explore options for sustainable funds that can be used to implement programs (14). Future research should focus on mapping the disease burden, control interventions, and monitoring and evaluation. Research regarding mass drug administration, screening, and prevalence is needed, as well as alternatives to mass drug administration (19).

There are currently limitations related to diagnosing scabies. Further research could help scientists better understand the pathobiology of scabies and identify specific biomarkers that could be used in a point-of-care rapid antigen test. If these tests could be developed cheaply and easily accessible by communities, they could be used to establish a standardized diagnosis (14).

Current medications used to treat scabies could be improved. The medications available do not relieve pruritus or provide anti-bacterial treatment. They also are unable to kill the mite eggs. Research regarding new medications that could include some of these elements and kill mites in all stages of their lifecycle would improve outcomes. Preclinical and clinical trials would be needed globally to assess the efficacy of any new medications. There is also not a vaccine available to treat scabies. Basic research is required to determine if a vaccine is possible. Further research will be needed to identify candidates for clinical trials and establish monitoring for vaccine programs (14).

There is no comprehensive awareness of the long-term health consequences of those who have experienced an infestation of scabies. Research is needed to provide molecular pathophysiological evidence of the link between scabies and opportunistic bacterial infections. In addition, more research is needed on how untreated scabies affect the cardiac and renal systems, as well as psychological consequences. Increased awareness would provide necessary information for healthcare workers and the general public and enable scabies to be recognized as a public health problem (14).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How could the WHO 2030 goals impact global scabies infections if they are accomplished?

- How can improving diagnostic methods improve outcomes?

- Why do new treatment methods continue to be researched?

- How does drug resistance impact scabies treatment research?

- How could current medications used for the treatment of scabies infestations be improved?

- How could a medication that kills scabies mites’ eggs impact disease prevalence?

- What are the benefits of increased public awareness related to scabies infestations?

- Why is it important to understand the long-term health outcomes of scabies infestations?

Conclusion

Scabies is a public health concern that affects many different areas of healthcare. This often-misdiagnosed parasitic infection can occur in any setting but is particularly common in areas of overcrowding, often where nurses are employed. Nurses who recognize assessment findings that suggest a scabies infection and understand how this disease is spread can improve outcomes for the populations they care for.

Scabies treatment often fails, but nurses knowledgeable in the treatment methods for scabies can provide effective patient education to reduce the spread and prevent reinfection. Nurses may have the opportunity to be involved in current and future research on scabies prevention and treatment, which would have a global impact. Nurses can improve global outcomes through thorough patient assessments and effective patient education.

References + Disclaimer

- World Health Organization. Scabies. 2023 5-31-23 2-11-25]; Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/scabies#:~:text=Scabies%20is%20a%20parasitic%20infestation%20caused%20by%20tiny%20mites%20that,heart%20disease%20and%20kidney%20problems.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Scabies. 2024 9-9-24 2-11-25]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/scabies/about/index.html.

- National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID), D.o.P.D.a.M. Scabies. 2024 6-6-24 2-11-25]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/scabies/index.html.

- Cleveland Clinic. Scabies. 2024 3-15-24 2-11-25]; Available from: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4567-scabies.

- Al-Dabbagh, J., R. Younis, and N. Ismail, The currently available diagnostic tools and treatments of scabies and variants: An updated narrative review. Medicine, 2023. 102(21): p. e33805. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10219715/

- Sharaf, M.S., Scabies: Immunopathogenesis and pathological changes. Parasitol Res, 2024. 123(3): p. 149 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/378700317_Scabies_Immunopathogenesis_and_pathological_changes

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Overview of Crusted Scabies. Parasites 2023 12-18-23 2-11-25]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/scabies/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html.

- Tai, D.B.G., O. Abu Saleh, and R. Miest, Genital nodular scabies. IDCases, 2020. 22: p. e00947 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7490806/

- Thomas, C., et al., Ectoparasites: scabies. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 2020. 82(3): p. 533-548 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0190962219323850

- Murray, R.L. and J.S. Crane. Scabies. 2023 7-31-23 2-15-25]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544306/.

- Yürekli, A., İ. Can, and M. Oğuz, Using ultraviolet light in diagnosing scabies: Scabies’ Sign via Wood’s Lamp. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 2023. 89(5): p. e195-e196 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37451622/

- Rauwerdink, D. and D. Balak, Burrow Ink Test for Scabies. New England Journal of Medicine, 2023. 389(7): p. e12 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37578077/ .

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How Scabies Spreads. 2024 2-23-24 2-21-25]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/scabies/causes/index.html.

- Fernando, D.D., et al., Scabies. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2024. 10(1): p. 74 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39362885/

- Mayo Clinic. Scabies. 2022 7-28-22 2-24-25]; Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/scabies/symptoms-causes/syc-20377378.

- Lam, J.M. and W. Rehmus, Scabies: a historical perspective. International Journal of Dermatology, 2024. 63(12): p. 1637 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ijd.17536

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Care of Scabies. 2023 12-18-23 2-26-25]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/scabies/hcp/clinical-care/index.html.

- Bernigaud, C., K. Fischer, and O. Chosidow, The Management of Scabies in the 21st Century: Past, Advances and Potentials. Acta Derm Venereol, 2020. 100(9): p. adv00112.

- Engelman, D., et al., A framework for scabies control. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2021. 15(9): p. e0009661 https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0009661

- Welch, E., L. Romani, and M.J. Whitfeld, Recent advances in understanding and treating scabies. Fac Rev, 2021. 10: p. 28 https://www.researc

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate