Course

Texas APRN Bundle

Course Highlights

- In this course, we will learn about Texas nursing jurisprudence and ethics.

- You’ll also learn the basics of sexual assault as a public health problem and its impact on the state of Texas.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of commonly prescribed opioids for pain management and understand their side effects and indications of use.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 20

Course By:

Various Authors

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

Texas Nursing Jurisprudence and Ethics

Texas Nursing Jurisprudence and Ethics

Introduction - Texas Nursing Jurisprudence and Ethics

The purpose of this course is to review nursing ethics and jurisprudence specifically as these relate to Texas state nursing practice and law (1). Each state nursing board works to promote the safety and welfare of clients in their state by ensuring nurses are competent to practice nursing safely.

As outlined by the Texas Board of Nursing continuing education requirements, Nursing Jurisprudence and Nursing Ethics Board Rule 216.3, all nurses, including APRNs, must complete the required two contact hours of CNE relating to nursing jurisprudence and ethics before the end of every third two-year licensing period. This requirement applies to licensing periods that began on or after January 1, 2014. All new nurses must also pass the Nursing Jurisprudence Exam (NJE) (2,3).

Requirements also outline that education includes information related to the Texas Nursing Practice Act, the Board's rules, including Standards of Nursing Practice, the Board's position statements, principles of nursing ethics, and professional boundaries. Nurses are named in negligence and malpractice lawsuits that may claim unethical behavior/conduct, practice outside the scope of licensure, or lack of nursing supervision. Nurses must understand their state nurse practice act, scope of practice of nurse licensure, standards of practice, ethics, and professional boundaries to avoid litigation (2).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What is the number of contact hours required by the Board of Nursing in Texas Nursing Jurisprudence and Ethics before the end of every third two-year licensing period?

- What are the categories of required course information that must be contained?

- What training have you had regarding Texas jurisprudence and ethics?

- How do you feel that ethics have changed throughout your years of practice?

- Where can you find Texas' nurse practice act?

The Texas Nursing Practice Act – Overview

Registered Nurse Scope of Practice

The Texas Nursing Practice Act (NPA) defines the legal scope of practice for professional registered nurses (RNs) (4). "Professional nursing" means performing an act that requires substantial specialized judgment and skill, the proper performance of which is based on knowledge and application of the principles of biological, physical, and social science as acquired by a completed course in an approved school of professional nursing. The term does not include acts of medical diagnosis or the prescription of therapeutic or corrective measures. Professional nursing involves: (4)

- the observation, assessment, intervention, evaluation, rehabilitation, care, and Counsel, or health teachings of a person who is ill, injured, infirm, or experiencing a change in normal health processes.

- The maintenance of health or prevention of illness.

- A physician, podiatrist, or dentist orders medication administration or treatment.

- The supervision or teaching of nursing.

- The administration, supervision, and evaluation of nursing practices, policies, and procedures.

- The requesting, receiving, signing for, and distributing prescription drug samples to patients at practices where an advanced practice registered nurse is authorized to sign prescription drug orders as provided by Subchapter B, Chapter 157.

- The performance of an act delegated by a physician under Section 157.0512, 157.054, 157.058, or 157.059.

- The development of the nursing care plan.

The RN accepts responsibility for practicing within the legal scope of practice, is prepared to work in all healthcare settings, and may engage in independent nursing practice without supervision by another healthcare provider. The RN, focusing on patient safety, must function within the legal scope of practice and by the federal, state, and local laws, rules and regulations, and policies, procedures, and guidelines of the employing health care institution or practice setting. The RN provides safe, compassionate, and comprehensive nursing care to patients and their families with complex healthcare needs (5).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What does the term "Professional nursing" mean?

- What is professional nursing performance based on in Texas nursing jurisprudence and ethics?

- Does professional nursing include medical diagnosis or the prescription of therapeutic or corrective measures?

- Does professional nursing involve the supervision or teaching of nursing or the development of the nursing care plan?

- Can an RN engage in independent nursing practice without the supervision by another health care provider?

Texas Nursing Jurisprudence and Ethics - Board Rules

Texas Board of Nursing, Chapter 217, Rule §217.11, Standards of Nursing Practice (6)

The Texas Board of Nursing regulates nursing practice within the State of Texas for Vocational Nurses, Registered Nurses, and Registered Nurses with advanced practice authorization. The standards of practice establish a minimum acceptable level of nursing practice in any setting for each level of nursing licensure or advanced practice authorization. Failure to meet these standards may result in action against the nurse's license even if no actual patient injury resulted (6).

- Standards Applicable to All Nurses. All vocational nurses, registered nurses, and registered nurses with advanced practice authorization shall:

- Know and conform to the Texas Nursing Practice Act, the Board's rules and regulations, and all federal, state, or local laws, rules, or regulations affecting the nurse's current area of nursing practice.

- Implement measures to promote a safe environment for clients and others.

- Know the rationale for and the effects of medications and treatments and shall correctly administer the same.

- Accurately and completely report and document:

- The client's status, including signs and symptoms, is as follows:

- Nursing care rendered.

- Physician, dentist, or podiatrist orders.

- Administration of medications and treatments.

- client response(s).

- contacts with other healthcare team members concerning significant events regarding the client's status.

- Respect the client's right to privacy by protecting confidential information unless required or allowed by law to disclose the information.

- Promote and participate in education and counseling to a client(s) and, where applicable, the family/significant other(s) based on health needs.

- Obtain instruction and supervision as necessary when implementing nursing procedures or practices.

- Make a reasonable effort to obtain orientation/training for competency when encountering new equipment and technology or unfamiliar care situations.

- Notify the appropriate supervisor when leaving a nursing assignment.

- Know, recognize, and maintain professional boundaries of the nurse-client relationship.

- Comply with mandatory reporting requirements of Texas Occupations Code Chapter 301 (Nursing Practice Act), Subchapter I, which includes reporting a nurse:

- Who violates the Nursing Practice Act or a board rule and contributed to the death or severe injury of a patient.

- Whose conduct causes a person to suspect that the nurse's practice is impaired by chemical dependency or drug or alcohol abuse?

- Whose actions constitute abuse, exploitation, fraud, or a violation of professional boundaries.

- Whose actions indicate that the nurse lacks knowledge, skill, judgment, or conscientiousness to such an extent that the nurse's continued practice of nursing could reasonably be expected to pose a risk of harm to a patient or another person, regardless of whether the conduct consists of a single incident or a pattern of behavior.

- Except for minor incidents (Texas Occupations Code §§301.401(2), 301.419, 22 TAC §217.16), peer review (Texas Occupations Code §§301.403, 303.007, 22 TAC §217.19), or peer assistance if no practice violation (Texas Occupations Code §301.410) as stated in the Nursing Practice Act and Board rules (22 TAC Chapter 217).

- Provide, without discrimination, nursing services regardless of the age, disability, economic status, gender, national origin, race, religion, health problems, or sexual orientation of the client served.

- Institute appropriate nursing interventions that might be required to stabilize a client's condition and prevent complications.

- Clarify any order or treatment regimen the nurse has reason to believe is inaccurate, non-efficacious, or contraindicated by consulting with the appropriate licensed practitioner and notifying the ordering practitioner when the nurse decides not to administer the medication or treatment.

- Implement measures to prevent exposure to infectious pathogens and communicable conditions.

- Collaborate with the client, members of the health care team, and, when appropriate, the client's significant other(s) in the interest of the client's health care.

- Consult with, utilize, and make referrals to appropriate community agencies and health care resources to provide continuity of care.

- Be responsible for one's continuing competence in nursing practice and individual professional growth.

- Make assignments to others that consider client safety and are commensurate with the educational preparation, experience, knowledge, and physical and emotional ability of the person to whom the assignments are made.

- Accept only those nursing assignments that consider client safety and are commensurate with the nurse's educational preparation, experience, knowledge, and physical and emotional ability.

- Supervise nursing care provided by others for whom the nurse is professionally responsible.

- Ensure the verification of current Texas licensure or other Compact State licensure privileges and credentials of personnel for whom the nurse is administratively responsible when acting in the role of nurse administrator.

- Standards Specific to Vocational Nurses. The licensed vocational nurse practice is a directed scope of nursing practice under the supervision of a registered nurse, advanced practice registered nurse, physician's assistant, physician, podiatrist, or dentist. Supervision is the process of directing, guiding, and influencing the outcome of an individual's performance of an activity. The licensed vocational nurse shall assist in the determination of predictable healthcare needs of clients within healthcare settings and:

- Shall utilize a systematic approach to provide individualized, goal-directed nursing care by:

- Collecting data and performing focused nursing assessments.

- Participating in the planning of nursing care needs for clients.

- Participating in developing and modifying the comprehensive nursing care plan for assigned clients.

- Implementing appropriate aspects of care within the LVN's scope of practice.

- Assisting in the evaluation of the client's responses to nursing interventions and the identification of client needs.

- Shall utilize a systematic approach to provide individualized, goal-directed nursing care by:

-

- Shall assign specific tasks, activities, and functions to unlicensed personnel commensurate with the educational preparation, experience, knowledge, and physical and emotional ability of the person to whom the assignments are made and shall maintain appropriate supervision of unlicensed personnel.

- May perform other acts that require education and training as prescribed by board rules and policies, commensurate with the licensed vocational nurse's experience, continuing education, and demonstrated licensed vocational nurse competencies.

- Standards Specific to Registered Nurses. The registered nurse shall assist in the determination of healthcare needs of clients and shall:

- Utilize a systematic approach to provide individualized, goal-directed nursing care by:

- Performing comprehensive nursing assessments regarding the health status of the client.

- Making nursing diagnoses serves as the basis for the care strategy.

- Developing a plan of care based on the assessment and nursing diagnosis.

- Implementing nursing care.

- Evaluating the client's responses to nursing interventions.

-

- Delegate tasks to unlicensed personnel in compliance with Chapter 224 of this title, relating to clients with acute conditions or in acute environments, and Chapter 225, relating to independent living environments for clients with stable and predictable situations.

- Standards Specific to Registered Nurses with Advanced Practice Authorization. Standards for a specific role and specialty of advanced practice nurses supersede standards for registered nurses where conflict between the standards, if any, exists. In addition to paragraphs (1) and (3) of this subsection, a registered nurse who holds authorization to practice as an advanced practice nurse (APN) shall:

- Practice in an advanced nursing practice role and specialty by the authorization granted under Board Rule Chapter 221 of this title (relating to practicing in an APN role; 22 TAC Chapter 221) and standards set out in that chapter.

- Prescribe medications in accordance with the prescriptive authority granted under Board Rule Chapter 222 of this title (relating to APNs prescribing; 22 TAC Chapter 222) and standards set out in that chapter and compliance with state and federal laws and regulations relating to the prescription of dangerous drugs and controlled substances. (4)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Why is it important for Texas Nursing Jurisprudence and Ethics that a nurse know the rationale for and the effects of medications and treatments before administering these to a client?

- Are there negative consequences if a nurse is not trained to perform a task or procedure? If so, what are 1-2 consequences of lack or training or errors?

- How do nurses utilize a systematic approach to providing individualized, goal-directed, nursing care?

- What challenges of appropriate delegation have you encountered and how have you over come them?

- What techniques have helped you to be successful in delegation?

The Board's Position Statements

15.28 The Registered Nurse Scope of Practice (See also the LVN Scope of Practice) (7)

The Board of Nursing recommends that all nurses utilize the Scope of Practice Decision-Making Model (DMM) when deciding if an employer's assignment is safe and legally within the nurse's scope of practice (8).

The Texas Board of Nursing (BON or Board) is authorized by the Texas Legislature to regulate the nursing profession to ensure that every licensee is competent to practice safely. The Texas Nursing Practice Act (NPA) defines the legal scope of practice for professional registered nurses (RN) (4, 9).

The RN takes responsibility and accepts accountability for practicing within the legal scope of practice, is prepared to work in all healthcare settings, and may engage in independent nursing practice without supervision by another healthcare provider. With a focus on patient safety, the RN must function within the legal scope of practice and in accordance with federal, state, and local laws, rules, and regulations. In addition, the RN must comply with policies, procedures, and guidelines of the employing health care institution or practice setting. The RN provides safe, compassionate, and comprehensive nursing care to patients and their families with complex healthcare needs (9).

This position statement aims to provide direction and recommendations for nurses and their employers regarding the safe and legal scope of practice for RNs and to promote an understanding of the differences in the RN programs of study and between the RN and LVN levels of licensure. The LVN scope of practice is interpreted in Position Statement (9).

Every nursing education program in Texas must ensure that their graduates exhibit competencies outlined in the Board's Differentiated Essential Competencies of Graduates of Texas Nursing Programs Evidenced by Knowledge, Clinical Judgements, and Behaviors. These competencies are included in the program of study so that every graduate has the knowledge, clinical judgment, and behaviors necessary for RN entry into safe, competent, and compassionate nursing care. The DECs serve as a guideline for employers to assist RNs in transitioning from the educational environment into nursing practice. As RNs enter the workplace, the DECs are the foundation for developing the RN scope of practice (9).

Completion of ongoing, informal continuing nursing education offerings and on-the-job training in an RN's area of practice serves to develop, maintain, and expand competency. Because the RN scope of practice is based upon the educational preparation in the RN program of study, there are limits to expanding the scope. The Board believes that successfully transitioning from one level of nursing practice to another requires the nurse to complete a formal education program. (10)

The RN Scope of Practice

The professional RN advocates for the patient and the patient's family and promotes safety by practicing within the NPA and the BON Rules and Regulations. The RN provides nursing services that require substantial specialized judgment and skill. The planning and delivery of professional nursing care are based on knowledge and application of biological, physical, and social science principles as acquired by a completed course of study in an approved school of professional nursing. Unless licensed as an advanced practice registered nurse, the RN's scope of practice does not include acts of medical diagnosis or the prescription of therapeutic or corrective measures. RNs utilize the nursing process to establish the plan of care in which nursing services are delivered to patients. The level and impact of the nursing process differ between the RN and LVN, as well as the levels of RN education (9).

Assessment

The comprehensive assessment is the first step and lays the foundation for the nursing process. The thorough evaluation is the initial and ongoing, extensive data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Nursing judgment is based on the assessment findings. The RN uses clinical reasoning and knowledge, evidence-based outcomes, and research as the basis for decision-making and comprehensive care (9).

Based upon the comprehensive assessment, the RN determines the physical and mental health status, needs, and preferences of culturally, ethnically, and socially diverse patients and their families using evidence-based health data and knowledge synthesis. Surveillance is an essential step in the comprehensive assessment process. The RN must anticipate and recognize changes in patient conditions and determine when reassessments are needed (9).

Patient Diagnosis/Problem Identification/Planning

The second step in the nursing process is nursing diagnosis and problem identification. The role of the RN is to synthesize comprehensive assessment data to identify problems, formulate goals/outcomes, and develop plans of care for patients, families, populations, and communities using information from evidence-based practice and published research in collaboration with these groups and the interdisciplinary health care team (9).

The third step in the nursing process is planning. The RN synthesizes the data collected during the comprehensive assessment to identify problems, make nursing diagnoses, and formulate goals, teaching plans, and outcomes. A nursing plan of care for patients is developed by the RN, who is responsible for coordinating nursing care for patients. Teaching plans address health promotion, maintenance, restoration, and risk factors prevention. The RN utilizes evidence-based practice, published research, and information from patients and the interdisciplinary healthcare team during the planning process (9).

Implementation

Implementing the plan of care is the fourth step in the nursing process. The RN may begin, deliver, assign, or delegate specific interventions within the care plan for patients within legal, ethical, and regulatory parameters and consider health restoration, disease prevention, wellness, and promotion of healthy lifestyles (9).

The RN's duty to patient safety when making assignments to other nurses or delegating tasks to unlicensed staff is to consider the education, training, skill, competence, and physical and emotional abilities of those to whom the assignments or delegation is made. The RN is responsible for reasonable and prudent decisions regarding assignments and delegation. The RN's scope of practice may include the supervision of LVNs or other RNs. Supervision of LVN staff is defined as the process of directing, guiding, and influencing the outcome of an individual's performance and activity. The RN may have to directly observe and evaluate the nursing care provided depending on the LVN's skills and competence, patient conditions, and level of urgency in emergent situations (9).

The RN may determine when to delegate tasks to unlicensed personnel and maintain accountability for how they perform the tasks. The RN is responsible for supervising the unlicensed personnel when tasks are delegated. The proximity of supervision depends upon patient conditions and the skill level of the unlicensed personnel. In addition, teaching and counseling are interwoven throughout the implementation phase of the nursing process. (10,11)

Evaluation and Reassessment

A critical and final step in the nursing process is evaluation. The RN evaluates and reports patient outcomes and responses to therapeutic interventions compared to benchmarks from evidence-based practice and research findings and plans any follow-up care and referrals to appropriate resources that may be needed. The evaluation phase is one of the times when the RN reassesses patient conditions and determines if interventions were effective and if any modifications to the care plan are necessary (9).

Essential Skills Used in the Nursing Process

Communication

Communication is an essential and fundamental component used during the nursing process. The RN must communicate verbally, in writing, or electronically with healthcare team members, patients, and their families in all aspects of the nursing care provided to patients. The patient record or nursing care plan must appropriately document these communications. Because RNs plan, coordinate, initiate, and implement a multidisciplinary team's approach to patient care, collaboration is crucial to communication. When patient conditions or situations exceed the RN's level of competency, the RN must be prepared to seek out other RNs with greater competency or other health care providers with differing knowledge and skillsets and actively cooperate to ensure patient safety (9).

Clinical Reasoning

Clinical reasoning is another integral component of the nursing process. RNs use critical thinking skills to problem-solve and make decisions in response to patients, their families, and the healthcare environment. RNs are accountable and responsible for the quality of nursing care provided and must exercise prudent and professional nursing judgment to ensure the standards of nursing practice are always met (9).

Employment Setting

When an employer hires an RN to perform a job, the RN must ensure that it is safe and legal. Caution must be exercised to stay within the legal parameters of nursing practice when an employer may not understand the limits of the RN's scope of practice and makes an assignment that is not safe. Before engaging in an activity or assignment, the RN must determine whether he or she has the education, training, skill, competency, and physical and emotional ability to carry out the activity or assignment safely. The RN must always provide patients with safe, compassionate, and comprehensive nursing care (9).

Summary of RN Scope of Practice

The RN, with a focus on patient safety, must function within the legal scope of practice and by the federal, state, and local laws, rules and regulations, and policies, procedures, and guidelines of the employing health care institution or practice setting. The RN functions under his or her license and assumes accountability and responsibility for the quality of care provided to patients and their families according to the standards of nursing practice. The RN demonstrates responsibility for continued competence in nursing practice and develops insight through reflection, self-analysis, self-care, and lifelong learning (9).

The table below offers a brief synopsis of how the scope of practice for nurses differs based on educational preparation and level of licensure. These are minimum competencies but also set limits on what the LVN or RN can do at his or her given level of licensure, regardless of experience (9).

Synopsis of Differences in Scope of Practice for Licensed Vocational, Associate, Diploma and Baccalaureate Degree Nurses (10)

Synopsis of Differences in Scope of Practice for Licensed Vocational, Associate, Diploma and Baccalaureate Degree Nurses (4)

| Nursing Practice |

LVN Scope of Practice Directed/Supervised Role |

ADN or Diploma RN Scope of Practice Independent Role |

BSN RN Scope of Practice Independent Role |

| Education |

|

|

|

| Setting |

|

|

|

| Assessment |

|

|

|

| Nursing Diagnosis/ Problem Identification/ Planning |

|

|

|

| Implementation |

|

|

|

|

Evaluation

|

|

|

|

Nursing board Position Statements are not laws, but they provide direction for nurses on issues of concern to the Board relevant to public protection. These Position Statements are reviewed annually for relevance and accuracy to current practice, the Nurse Practice Act, and Board of Nursing rules. Examples of Position Statements include the following: (9)

- Nurses Carrying out Orders from Physician Assistants

- Role of the Licensed Vocational Nurse in the Pronouncement of Death

- LVNs Engaging in IV Therapy, Venipuncture, or PICC Lines

- Educational Mobility

- Nurses with Responsibility for Initiating Physician Standing Orders

- Board Rules Associated with Alleged Patient "Abandonment"

- The Role of LVNs & RNs in the Management and Administration of Medications via Epidural or Intrathecal Catheter Routes

- The Role of the Nurse in Moderate Sedation

- Performance of Laser Therapy by RNs or LVNs

- Continuing Education: Limitations for Expanding Scope of Practice

- Delegated Medical Acts

- Use of American Psychiatric Association Diagnoses by LVN, RNs, or APRNs

- Role of LVNs & RNs As School Nurses

- Duty of a Nurse in any Practice Setting

- Board's Jurisdiction Over a Nurse's Practice in Any Role and Use of the Nursing Title

- Development of Nursing Education Programs

- Texas Board of Nursing/Board of Pharmacy Joint Position Statement on Medication Errors

- Nurses Carrying Out Orders from Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRN)

- Nurses Carrying Out Orders from Pharmacists for Drug Therapy Management

- Registered Nurses in the Management of an Unwitnessed Arrest in a Resident in a Long-Term Care Facility (9)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

-

What are advantages for nurses to consistently use the nursing process during care and documentation of care of clients?

-

How could communication breakdown among employee nurse team members impact a client's care?

-

Are nursing board Position Statements laws?

-

Name one example of a nursing board Position Statement.

-

What do RNs use to problem-solve and make decisions regarding care of clients, when it comes to Texas Nursing Jurisprudence and Ethics?

Principles of Texas Nursing Jurisprudence and Ethics

Professional Boundaries

15.29 Professional Boundaries including use of social media by nurses (11)

The purpose of this Position Statement is to guide nurses regarding expectations related to professional boundaries, including social media, and to provide nurses with guidance to prevent boundary violations (5).

In keeping with its mission to protect public health, safety, and welfare, the Texas Board of Nursing (BON or Board) holds nurses accountable for knowing, recognizing, and maintaining professional boundaries of the nurse-patient/client relationship. The term professional boundaries is defined as the appropriate limits that the nurse should establish in the nurse/client relationship due to the nurse's power and the patient's vulnerability. Professional boundaries refer to the provision of nursing services within the limits of the nurse/client relationship, which promote the client's dignity, independence, and best interests and refrain from inappropriate involvement in the client's relationships and the obtainment of the nurse's gain at the client's expense (5).

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) defines professional boundaries as the spaces between the nurse's power and the patient's vulnerability. The nurse's power comes from the nurse's professional position and access to sensitive personal information. The difference in personal information the nurse knows about the patient versus the personal information the patient knows about the nurse creates an imbalance in the nurse-patient relationship. Nurses should respect the power imbalance and ensure a patient-centered relationship (5).

Common to the definition of professional boundaries from the Texas Board of Nursing and the NCSBN is that a nurse abstains from personal gain at the client's expense and refrains from inappropriate involvement with the patient or the patient's family (5).

Duty of a Nurse in Maintenance of Professional Boundaries

There is a power differential between the nurse and the patient. The patient depends on the nurse's knowledge and relies on the nurse to advocate for the patient and ensure actions are taken in the patient's best interest. The nurse must protect the patient, establishing and maintaining professional boundaries in the nurse-patient/client relationship. Under or over-involvement can harm the patient and may interfere with the nurse-patient relationship. Visualizing the two ends of the spectrum may assist the nurse in knowing, recognizing, and maintaining the professional boundaries of nurse-patient relationships (5).

Patients each have their own unique needs and abilities. The boundary line for any one patient may change over time and may not be the same as the boundary line for another patient. It is up to the nurse to assess and recognize the patient's needs, adjusting the nursing care accordingly. Every nurse is responsible for knowing, identifying, and maintaining the professional boundaries of the nurse-client relationship (5).

Boundary Violations

A violation of professional boundaries is one element of the definition of "conduct subject to reporting [Tex. Occ.Ide Sec. 301.401(1)(C)]. A professional boundary violation is also considered unprofessional conduct [22 TAC §217.12 (6)(D)]. Some of the specific categories of professional boundary violations include but are not limited to, physical, sexual, emotional, or financial boundary violations (5).

Use of Social Media and the Protection of Health Information

Social media and other electronic communication are expanding exponentially as the number of social media outlets, platforms, and applications available continues to increase. Nurses play a significant role in identifying, interpreting, and transmitting knowledge and information within healthcare. As technological advances expand connectivity and communication, rapid knowledge exchange and dissemination can pose risks to patients and nurses. While the Board recognizes that using social media can be a valuable tool in healthcare, there are potentially severe consequences if misused. A nurse's use of social media may cause the nurse to unintentionally blur the lines between the nurse's professional and personal life (5).

Online postings may harm patients if protected health information is disclosed. In addition, social media postings may reflect negatively on individual nurses, the nursing profession, the public's trust in the nursing profession, or the employer and may jeopardize careers. In an NCSBN survey, many responding boards reported receiving complaints about nurses misusing social media sites. The survey results indicated that boards fired by employers have disciplined nurses and are criminally charged for the inappropriate or unprofessional use of social media (5).

To ensure the mission to protect and promote the welfare of the people of Texas, the Texas Board of Nursing supports the guidelines and principles of social media use by the NCSBN and the American Nurses Association. By the NCSBN guidelines and Board rules, it is the Board's position that (5):

Nurses have an ethical and legal obligation to maintain patient privacy and confidentiality. When using social media, nurses do not identify patients by name or post or publish information that may lead to patient identification. Limiting access to postings through privacy settings is not sufficient to ensure privacy. Nurses must promptly report any identified breach of confidentiality or privacy (5).

Nurses maintain professional boundaries in the use of electronic media. The nurse must establish, communicate, and enforce professional boundaries with patients online. Nurses do not refer to patients disparagingly, even if the patient is not identified, or transmit information that may be reasonably anticipated to violate patient rights to confidentiality or privacy or otherwise degrade or embarrass the patient (5).

Nurses must provide nursing services without discrimination and not make threatening, harassing, profane, obscene, sexually explicit, racially derogatory, homophobic, or other offensive comments (5).

Nurses must be aware of and comply with all laws and rules, including employer policies regarding using electronic devices, including employer-owned computers, cameras, and personal devices. In addition, nurses must ensure appropriate and therapeutic use of all patient-related electronic media, including patient-related images, photos, or videos, by applicable laws, rules, and institutional policies and procedures (5).

The use of social media can be of tremendous benefit to nurses and patients alike, for example, the dissemination of public safety announcements. However, nurses must know the potential consequences of disclosing patient-related information via social media. Nurses must always maintain professional standards, boundaries, and compliance with local, state, and federal laws. All nurses must protect their patients' privacy and confidentiality, which extends to all environments, including social media (5).

The following are ways to avoid problems when using social media:

- Never post any healthcare-related images, client information, or even general client information

- Only use your organization's name or a client or family member's name to post content about or speak for your employer if your organization authorizes you to follow their specific policy and procedures.

- Never post comments about a client, even if the client is not named.

- Never post photos or videos of your healthcare organization or clients

- Never post any comments about your employer or other team members

- Never use obscenity, profanity, racial slurs, sexually inappropriate comments, homophobic comments, threats, harassing/abusive language, or any other offensive comments. Never post any image that contains the above content.

Prevention of Boundary Violations

The ability of a client to rely on employees as concerned and caring individuals who remain objective in their guidance is one of the tents of a safe, therapeutic relationship. The relationship may no longer be objectively therapeutic when staff interacts with patients personally. Accepting gifts, financial transactions, and romantic entanglement could lead to various negative consequences for an organization, employee, or client. Many organizations enforce a non-fraternization policy between employees and current or former clients. While there are exceptions, the expectation is that employees are not to establish a personal relationship with a current or former client. Organizations do recognize that there are times when peers, friends, family, or neighbors of employees seek treatment. In these circumstances, the relationship must remain the nature it was before admission if in the client's best interest, and the treatment plan should address the relationship to best meet the client's therapeutic needs. Employees should also notify a supervisor when an individual with whom he or she has a relationship is admitted for treatment (5).

Texas Nurses are required to comply with mandatory reporting requirements of Texas Occupations Code Chapter 301 NPA Subchapter I, which include reporting a nurse (11):

- Who violates the NPA or a board rule and contributed to the death or severe injury of a patient.

- Whose conduct causes a person to suspect that the nurse's practice is impaired by chemical dependency or drug or alcohol abuse?

- Whose actions constitute abuse, exploitation, fraud, or a violation of professional boundaries.

- Whose actions indicate that the nurse lacks knowledge, skill, judgment, or conscientiousness to such an extent that the nurse's continued practice of nursing could reasonably be expected to pose a risk of harm to a patient or another person, regardless of whether the conduct consists of a single incident or a pattern of behavior.

The exception is for minor incidents, peer review, or peer assistance if there is no practice violation as stated in the Nursing Practice Act and Board rules (6, 11).

Organizations also take many precautions to ensure appropriate employee-client relationships, including (13):

- Criminal background checks of employees

- Employee, student, and volunteer education regarding therapeutic boundaries and issues and consequences of any violations

- Mandatory, supportive, and confidential reporting of any violation

Employee supervision also includes the identification of early signals that an employee may be crossing therapeutic boundaries and the institution of appropriate interventions. Employees educate clients regarding the importance of maintaining a therapeutic relationship and proper boundaries. Organizations work to ensure adequate supervision of staff and appropriate supervision of clients, such as increased observation or same-gender staff working with a client when appropriate (13).

There must be mandatory reporting by any employee who becomes aware of a boundary violation. The employee should report this immediately to their supervisor, who will evaluate the nature and severity of the claim and initiate an investigation of the situation. In conjunction with Human Resources and Risk Management, the immediate supervisor will determine whether an accused employee should be put on immediate leave pending investigation results and whether mandatory reporting of the allegations to outside agencies is required. Legal Counsel may also be consulted when necessary. An employer may not suspend or terminate employment or otherwise discipline, retaliate, or discriminate against a person who reports, in good faith, or advises a nurse of the nurse's rights and obligations (5, 9, 11, 12).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Why is it important to Texas Nursing Jurisprudence and Ethics for a nurse to maintain professional and appropriate boundaries with a client?

- Name two examples of how social media may cause a nurse to blur the lines between his/her personal and professional life?

- Is reporting of boundary violations mandatory? If so, name two examples of when a nurse should report.

- How do organizations take precautions to ensure appropriate employee-client relationships?

- List two examples of nurses whom a nurse in Texas would report for violations of the Nurse Practice Act.

Unprofessional Conduct - Rule §217.12

The following unprofessional conduct rules are intended to protect clients and the public from incompetent, unethical, or illegal conduct of licensees. The purpose of these rules is to identify behaviors in the practice of nursing that are likely to deceive, defraud, or injure clients or the public. Actual injury to a client need not be established. These behaviors include but are not limited to: (all from 5)

1.Unsafe practice – actions or conduct including, but not limited to:

- Carelessly failing, repeatedly failing, or exhibiting an inability to perform vocational, registered, or advanced practice nursing in conformity with the standards of a minimum acceptable level of nursing practice set out in §217.11 of this chapter.

- Failing to conform to generally accepted nursing standards in applicable practice settings.

- Improper management of client records.

- Delegating or assigning nursing functions or a prescribed health function when the delegation or assignment could reasonably be expected to result in unsafe or ineffective client care.

- Accepting the assignment of nursing functions or a prescribed health function when the acceptance of the assignment could be reasonably expected to result in unsafe or ineffective client care.

- Failing to supervise the performance of tasks by any individual working pursuant to the nurse's delegation or assignment.

- Failure of a clinical nursing instructor to adequately supervise or to assure adequate supervision of student experiences.

2. Failure of a chief administrative nurse to follow standards and guidelines required by federal or state law or regulation or by facility policy in providing oversight of the nursing organization and nursing services for which the nurse is administratively responsible.

3. Failure to practice within a modified scope of practice or with the required accommodations, as specified by the Board in granting an encumbered license or any stipulated agreement with the Board.

4. Conduct that may endanger a client's life, health, or safety.

5. Inability to Practice Safely – a demonstration of actual or potential inability to practice nursing with reasonable skill and safety to clients by reason of illness, use of alcohol, drugs, chemicals, or any other mood-altering substances, or as a result of any mental or physical condition.

6. Misconduct – actions or conduct that include, but are not limited to:

- Falsifying reports, client documentation, agency records, or other documents.

- Failing to cooperate with a lawful investigation conducted by the Board.

- Causing or permitting physical, emotional, or verbal abuse or injury or neglect to the client or the public, or failing to report same to the employer, appropriate legal authority and/or licensing Board.

- Violating professional boundaries of the nurse/client relationship including but not limited to physical, sexual, emotional, or financial exploitation of the client or the client's significant other(s).

- Engaging in sexual conduct with a client, touching a client in a sexual manner, requesting, or offering sexual favors, or language or behavior suggestive of the same.

- Threatening or violent behavior in the workplace.

- Misappropriating, in connection with the practice of nursing, anything of value or benefit, including but not limited to, any property, real or personal of the client, employer, or any other person or entity, or failing to take precautions to prevent such misappropriation.

- Providing information, which was false, deceptive, or misleading in connection with the practice of nursing.

- Failing to answer specific questions or providing false or misleading answers in a licensure or employment matter that could reasonably affect the decision to license, employ, certify, or otherwise utilize a nurse.

- Offering, giving, soliciting, or receiving, or agreeing to receive, directly or indirectly, any fee or other consideration to or from a third party for the referral of a client in connection with the performance of professional services.

7. Failure to pay child support payments as required by the Texas Family Code §232.001, et seq.

8. Drug diversion – diversion or attempts to divert drugs or controlled substances.

9. Dismissal from a board-approved peer assistance program for noncompliance and referral by that program to the Board.

10. Other drug-related actions or conduct that include, but are not limited to:

- Use of any controlled substance or any drug, prescribed or unprescribed, or device or alcoholic beverages while on duty or on call and to the extent that such use may impair the nurse's ability to safely conduct to the public the practice authorized by the nurse's license.

- Falsification of or making incorrect, inconsistent, or unintelligible entries in any agency, client, or other record pertaining to drugs or controlled substances.

- Failing to follow the policy and procedure in place for the wastage of medications at the facility where the nurse was employed or working at the time of the incident(s).

- A positive drug screen for which there is no lawful prescription.

- Obtaining or attempting to obtain or deliver medication(s) through means of misrepresentation, fraud, forgery, deception and/or subterfuge.

11. Unlawful practice – actions or conduct that include, but are not limited to:

- Knowingly aiding, assisting, advising, or allowing an unlicensed person to engage in the unlawful practice of vocational, registered, or advanced practice nursing.

- Violating an order of the Board, or carelessly or repetitively violating a state or federal law relating to the practice of vocational, registered, or advanced practice nursing, or violating a state or federal narcotics or controlled substance law.

- Aiding, assisting, advising, or allowing a nurse under Board Order to violate the conditions set forth in the Order.

- Failing to report violations of the Nursing Practice Act and/or the Board's rules and regulations.

12. Leaving a nursing assignment, including a supervisory assignment, without notifying the appropriate personnel.

There is a Texas State Board of Nursing Disciplinary Matrix that nurses can review to see the process followed when a review of a nurse's conduct is necessary. The Board will consider public safety, the seriousness of the violation, and any aggravating or mitigating factors. Other factors considered include the presence of multiple violations, prior violations, and costs which could result in a more severe disciplinary action. (13)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Name two examples of unsafe nursing practice that will result in a nursing board review.

- Is violating boundaries of the employee-client relationship considered misconduct?

- Is failing to report violations of the Nursing Practice Act misconduct?

- Is failing to report violations of the Nursing Board's rules and regulations misconduct?

- Name two examples of unsafe nursing practice that will result in a nursing board review.

- Is violating boundaries of the employee-client relationship considered misconduct?

- Is failing to report violations of the Texas Nursing Jurisprudence and Ethics misconduct?

- Is failing to report violations of the Nursing Board's rules and regulations misconduct?

- What qualifies as an unlawful practice?

- What policies does your facility have regarding drug screening and reporting?

Provisions of the Code of Ethics for Nurses

Provision 1

The nurse practices with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person. (1)

Provision 2

The nurse's primary commitment is to the patient, whether an individual, family, group, community, or population. (1)

Provision 3

The nurse promotes, advocates for, and protects the rights, health, and safety of the patient. (1)

Provision 4

The nurse has authority, accountability, and responsibility for nursing practice, makes decisions, and takes action consistent with the obligation to provide optimal patient care. (1)

Provision 5

The nurse owes the same duties to self as to others, including the responsibility to promote health and safety, preserve wholeness of character and integrity, maintain competence, and continue personal and professional growth. (1)

Provision 6

The nurse, through individual and collective effort, establishes, maintains, and improves the ethical environment of the work setting and conditions of employment that are conducive to safe, quality health care. (1)

Provision 7

The nurse, in all roles and settings, advances the profession through research and scholarly inquiry, professional standards development, and the generation of both nursing and health policy. (1)

Provision 8

The nurse collaborates with other health professionals and the public to protect human rights, promote health diplomacy, and reduce health disparities. (1)

Provision 9

The profession of nursing, collectively through its professional organizations, must articulate nursing values, maintain the integrity of the profession, and integrate principles of social justice into nursing and health policy. (1)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Who is a Texas nursing jurisprudence and ethics-oriented nurse primarily committed to?

- Name two examples of how a nurse advocates for a client.

- Name three ways a nurse committed to Texas nursing jurisprudence and ethics protects a client's rights.

- Which of the abovementioned provisions have you found to be the most challenging to meet?

- What resources are available in your area to help navigate difficult ethical situations?

Case Study

Rachel is a 13-year-old adolescent female client admitted to an inpatient behavioral health unit for bipolar disorder, alcohol and marijuana abuse, and borderline personality disorder. The client has a history of sexual promiscuity, lying, and has alleged abuse and rape by history. Rachel approaches the Charge RN at bedtime, saying that an employee and she "have been having sex" many times over the course of two weeks and that she realizes now that "she should have told someone". The alleged employee is currently on duty.

As Charge RN, using what you learned about Texas Nursing Jurisprudence and Ethics, how would you respond, and what are your next steps?

Conclusion - Texas Nursing Jurisprudence and Ethics

When a nurse is named in a negligence or malpractice lawsuit, it can create stress for the client, the employee, and the employer. A nurse maintaining professional, ethical, and jurisprudent conduct will help to ensure standards of practice are consistently followed. Maintaining appropriate boundaries with clients at all times helps maintain a therapeutic employee-client relationship.

It is important that nurses understand their state nurse practice act, the scope of practice of nurse licensure, standards of practice, ethics, and professional boundaries in order to maintain professionalism, meet performance standards, and avoid a breach of duty, injury, and litigation.

Resources

Educational Requirements:

Texas Board of Nursing (2010), Differentiated Essential Competencies (DECs) of graduates of Texas Nursing Programs. (12)

Texas Occupations Code, Chapter 301 (12)

Nursing Practice Act (NPA) Section 301.002, Definitions (12)

Rule 217.11 - Standards of Nursing Practice (12)

Scope of Practice Position Statements: (12)

- Position Statement 15.28 The Registered Nurse Scope of Practice Web version for viewing

- Position Statement 15.14 - Duty of a Nurse Web version for viewing

- Position Statement 15.14 - Duty of a Nurse - HHSC/DADS/BON poster

For the complete list of position statements, click here. (12)

Texas Nursing Forensics

Texas Nursing Forensics

Introduction

In the United States, sexual assault was historically considered a judicial problem; however, it is now considered a major public health concern because of the health and psychological effects on individuals. The problem most notably emerged in the public eye in the 1960s with the women's liberation movement. In recent times the #METOO movement has increased awareness of the problem, and many organizations have surfaced to assist the assaulted. This course will focus on the problem in rural areas in the state of Texas and how nurses working in these facilities can best assist patients who have been sexually assaulted.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Aside from the hospital, what other setting might you encounter victims of sexual assault?

- In your opinion, what factors contribute to limited care for victims of sexual assault in rural areas?

- What types of psychological problems do you suspect victims of sexual assault may struggle with?

- When was the last time you received training in nursing forensics?

- How has the assessment and management of victims of assault changed since you have been in practice?

- Have you seen an increased incidence of sexual assault occur since you have been in practice? How has your facility managed the change?

- How has technology impacted the reporting and documenting of assault?

- What policies and procedures does your facility have regarding victims of assault?

- What resources does your community offer to help victims of assault?

- What policies does your facility have regarding the management of forensics in victims of assault?

Statistical Evidence

National Statistics

According to the Rape Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN) (1), every 68 seconds someone is sexually assaulted in the United States, and every nine minutes, that victim is a child (1). Only 25 out of every 1,000 perpetrators will end up in prison (1).in less than every 80 seconds, a person is sexually assaulted. In 2015 the Texas Statewide Sexual Assault Prevalence Study found that 33.2% of adult Texans or 413,000 individuals reported having been sexually assaulted at some point during their lives (2).

Each year in the United States (1):

- 80,600 inmates are sexually assaulted or raped

- 60,000 children were victims of “substantiated or indicated” sexual abuse

- 433,648 people 12 and older were sexually assaulted or raped

- 18,900 military personnel experienced unwanted sexual contact

- 1 out of every 6 women have been the victim of attempted or completed rape in her lifetime (14.8% completed, 2.8% attempted)

- 1 in 3 men have experienced an attempted or completed rape in their lifetime

- More women and children are sexually assaulted than men, and that girls under 18 years of age are at the highest risk. According to RAINN (1), men and boys, especially college-aged, are also at risk with transgender students at the highest risk of this group.

Most common locations where sexual assault occurs in the U.S. (1):

- 55% at or near the victim’s home

- 15% in an open public space

- 12% at or near a relative’s home

- 10% in an enclosed but public area (i.e. parking garage or lot)

- 8% on school property

Activities the victims were doing when they were assaulted (1):

- 48% were sleeping or performing another activity at home

- 29% were traveling to and from work or school, or traveling to shop or run errands

- 12% were working

- 7% were attending school

- 5% were doing an unknown or other activity

Sexual Assault on Children (1):

- 1 in 9 girls and 1 in 20 boys under the age of 18 experience sexual abuse or assault

- 2 out of 3 victims of sexual assault or rape (under the age of 18) are age 12 – 17

- Victims of sexual assault or rape under the age of 18 are about 4 times more likely to develop symptoms of drug abuse and PTSD as adults, and about 3 times more likely to experience a major depressive episode as adults

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What statistic surprised you the most? Why?

- Do you feel that these statistics represent what you see in your area? Why do you think that is the case?

- What factors do you think contribute the highest number of sexual assault cases occurring in the home?

- What are some strategies to help victims feel safe reporting their sexual assault?

- What strategies can communities use to protect children from sexual assault?

- In your opinion, what factors impact the reduced reporting from men after being sexually assaulted?

- What education can you provide to victims regarding the incidence of sexual assault?

- What policies does your facility have regarding children who are suspected victims of assault?

- What role does a community and or public health nurse play in the education and prevention of sexual assault?

- How has the education and management of sexual assault prevention changed since you have been in practice?

Texas Statistics

The latest statistics on sexual assault in the state of Texas were from 2018 and is as follows (2):

- Total number of reported sexual assault incidents was 19,816, a 9.4% increase from the prior year

- Of victim-to-offender relationships, 11% were romantic, 14% parental/child, 19% other family, and 55% other.

- Victims were 88% were female and 12% male

- Victims who were aged 10 – 14 were the group with highest number of cases

- Of all victims, 82% were white, 17% black, and 1% American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, or Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander

Location of sexual assault incidents in Texas in 2018 (2):

- 16,015 in residents/homes

- 2,041 in unknown or other areas

- 657 in a hotel/motel

- 718 in school/college

- 710 in a highway/road/alley

- 506 in a parking lot/garage

- 268 in fields/woods

- 185 in commercial/office buildings

- 176 in drug stores, doctor’s offices, or hospitals

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Do you think the care should be different for a patient sexually assaulted by a family member versus a romantic partner?

- The age of sexual assault is younger in Texas (10 to 14) than the country (12 to 17). What strategies can Texas employ for prevention?

- What is the benefit of knowing statistical evidence about sexual assault?

- What might need to be considered when caring for a male patient who had been sexually assaulted versus a female patient?

- What are your thoughts on the incidence of sexual assault in Texas in comparison to that of the U.S.?

- Have you seen an increase in sexual assault in your area? What do you feel has contributed to that?

- Do you feel that the Texas statistics listed above are accurate? Or do you think that they are higher or lower? Why?

- Which population group have you encountered most frequently in practice?

- How does your education and communication change in different genders, ages, and ethic groups who are victims of sexual assault?

- What prevention techniques have you seen to help prevent the incidence of sexual assault?

The Basics: Sexual Assault

What is Sexual Assault?

Sexual assault, also termed sexual violence, is described as “any type of unwanted sexual contact, including words and actions of a sexual nature against a person’s will and without their consent; a person may use force, threats, manipulation, or coercion to commit sexual violence” (3). Sexual assault is often defined separate from rape. Rape consists of penetration, whether vaginally, anally, or orally. Sexual assault is any type of unwanted sexual content and is not limited to rape. Sexual abuse, as described by the American Psychological Association (APA) "is unwanted sexual activity, with perpetrators using force, making threats or taking advantage of victims not able to give consent" (3). Assault can be the product of domestic abuse, gang violence, date rape, and incest. Assault can be inflicted on any age or gender and often occurs by someone who is related to or knows the victim.

What is SANE?

In many parts of the United States, Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANE), nurses who are expertly trained in performing forensic examinations and collection of evidence, are utilized (5). SANEs are nurses who specialize in forensic nursing. In forensic nursing, the health and legal system intersect (10). SANE programs began as early as the 1970s. At that time, nurses noticed that victims of sexual assault were not provided high quality care like other patients were in the emergency department. Nurses also noticed that the victims were very concerned about STDs and pregnancy and needed special treatment. Over the next 20 years, the forensic specialty grew, and the First SANE programs were started in Tennesse, Minnesota, and Texas. Today, Texas registered nurses working in the emergency departments must learn the SANE process to perform the forensics exams and evidence collection by completing a 2-hour educational program.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Why do you think sexual assault has changed from a judicial problem to a health problem?

- How can nurses contribute to a decrease in the costs associated with sexual assault?

- What organizations in Texas can you connect with to learn more about sexual assault and how you can impact the problem?

- Where can you find more information on SANE programs?

- What additional training can you complete to help better prepare you to manage sexual assault victims?

- What is the definition of sexual assault?

- How many nurses are available in your facility who are SANE nurses?

- What resources does your facility and community offer to help pay for the cost of becoming a SANE nurse?

- What additional resources are you aware of to assist with the management of sexual assault victims?

- What barriers to identifying sexual assault have you encountered? How have you overcome them?

Nursing's Role

Sexual assault is an extremely traumatic experience. Those affected can have a wide range of issues, emotionally, spiritually, physically, and psychologically. Nurses working in the emergency department are often first responders. Compassion, empathy, and privacy are a hallmark of excellent practice when caring for patients who have been sexually assaulted.

Many patients will experience shock and disbelief. "Why me? Will I be okay?" or "It's no big deal, I'm fine" (6). There may be "fear of responses from friends, family, the public, and criminal justice providers" (7). Victims of rape may also have concerns about pregnancy, STIs, and HIV/AIDS. These patients may feel their world has turned upside down. They may be scorned, told it was deserved, and fear their names could be made public (7).

In order to provide excellent care, all gender identities must be taken into consideration, as well as age and sexual orientation. No bias or judgment should be displayed to the patient. Customs, beliefs, religious, and spiritual needs should also be considered during the visit

Team Collaboration

Working with all personnel in the emergency department is essential. From paramedics, law enforcement officers, family, or anyone accompanying the patient to physicians, social workers, and forensic medical examiners, each professional has a specific skill set and role in the patient's care. Teamwork among these groups of individuals will provide the best possible outcomes for the patient. Team members involved in a victim’s care may include (8):

- “Community-based advocates

- Law enforcement officers

- SANEs, physicians or nurses trained in sexual assault medical forensic evidence collection

- Law enforcement victim service advocates

- District Attorney’s Office personnel, legal victim advocates and attorneys”

Interview

The interviewing nurse should actively listen, believe what the patient discloses, validate the patient’s feelings, maintain confidentiality, and honor the patient’s decisions on what to do about the assault. When caring for patients who have sexually assaulted, treating the whole person rather than the "problem" alone is vital. Repeating information back to the patient can help to elicit more precise information. Repeating information can also help to validate what the patient is saying, creating an atmosphere of trust. Consider that patients may not want to talk about the assault, as reliving it could bring out unwanted emotions.

If the patient arrives alone, the nurse should inquire if the patient wants a companion or an advocate to be present. An advocate could be a family member, friend, member of the clergy, or social worker. The patient can choose if they want someone present. Care must be taken to ensure the patient feels comfortable, as the presence of someone emotionally involved (or even the assaulter themselves) may deter the patient from being open and honest. An interpreter should also be arranged if needed, with the patient's consent.

If the patient has not alerted the local police, the nurse should inquire if they wish to report the assault and if so, the police should then be called. If available, a sexual assault response team (SART) should be immediately contacted. It is of the utmost importance to remember that the patient always makes the primary decision of what to do surrounding the case. Also, the patient must give consent first before any decisions are made. Admitting the patient to a private room in a quiet area of the emergency department lessens interruptions from outside sources.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Does your facility have a Sexual Assault Response Team (SART)?

- Have you ever taken care of a patient who had been sexually assaulted?

- What are some strategies you can employ if your emergency department does not have a private room to interview a victim of sexual assault?

- What is the protocol at your facility if a parent brings their child into the emergency department with sexual assault injuries?

- What techniques during the interview process of a sexual assault victim have you found to be unsuccessful?

- What techniques during the interview process of a sexual assault victim have you found to be successful?

- What types of collaboration have you seen in the facilities where you have worked?

- What role does law enforcement play in managing victims of sexual assault?

- What education do you provide to patients regarding STIs after sexual assault?

- How do you ensure the privacy of victims after admitting them to the hospital?

Assessment

After obtaining consent to perform the assessment, the patient should be advised of every step before each part of the exam. The patient should be informed they have total control of what is happening. It is important for the nurse to help the patient understand they always have the right to refuse any and all steps in the examination.

When performing the initial assessment and gathering information, documentation must include a very detailed and complete history, including any physical trauma to the patient’s body. The history should include any bruises, lacerations, or other visual injuries and how and when they occurred. The nurse should perform the interview slowly, giving the patient time to process and answer each question. The patient may or may not want to identify the person who assaulted them and should not be coerced into doing so.

A complete medical, surgical, and gynecologic history, in the case of a female patient, and any new symptoms occurring after the assault should be asked. Drug allergies, medications, and any alcohol or illegal drugs used at the time of the event are also documented. A compassionate and empathic tone should always be used to allow the patient to feel safe. The patient should not feel any judgment from any emergency department personnel. Patients should be given the opportunity and encouraged to grieve and react during this time. They should feel comfortable enough to ask and answer questions throughout the interview.

According to Texas law, nurses must obtain written consent from the patient. During the complete physical exam, the nurse will be charged with ensuring physical evidence of the assault from clothing or body fluids is not disturbed. Also, during this time, suicidality and emotional support should be assessed. Providing expert treatment for patients who have been sexually assaulted is of utmost importance. When available, a SANE nurse will perform the forensic examination. This examination is vital to collect and preserve physical evidence from the patient while also assessing life and limb injuries. If a SANE nurse is unavailable, as may be the case in Texas's rural areas, a "medical forensic examiner" will perform the examination.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How would you handle a situation in which a patient who has recently been sexually assaulted does not want to participate in the physical assessment?

- Are you familiar with medical forensic examiners?

- How often does your facility audit documentation?

- How might a nurse address their own biases when caring for a victim of sexual assault?

- What barriers to assessment have you encountered? How have you overcome them?

- Do you have to receive written consent from a patient before a physical exam?

- What policies does your facility have regarding the psychosocial assessment of patients of sexual assault?

- How do you ensure that your patient stays informed of their care while respecting their emotions?

- How can a complete medical, surgical, and gynecological history improve patient care and outcomes?

- What is a medical forensic examiner?

Documentation

When documenting the case, the nurse should use open-ended questions to elicit the patient's best and clearest responses. Documentation must be complete and exact, including every stage of the assault with times, dates, and descriptions, with consideration for the patient's emotional state and ability to recall. Using motivational interviewing can be helpful as well. Documenting in the patient’s own words is best practice. Nurses should try their best to document all of the following about the case (8):

- “All those present during the patient’s history and examination

- Time, date, and location of assault(s)

- Contact and/or penetrative acts by suspect(s)

- Was the suspect injured in any way, if known?

- Use of lubricant, including saliva

- Patient’s actions between the sexual assault and arrival at the facility (brushing teeth, using mouthwash, smoking, vaping, changing clothes, vomiting, swimming, showering, or bathing)

- Was a condom used?

- Did ejaculation occur? Where?

- Any weapon use or physical force, or threat of weapon use or physical force?

- Description of condition of clothing (and was clothing torn or stained prior to assault?)”

In the case of a minor, a parent will give consent, and if no parent is available or is the assaulter, the child will be turned over to the appropriate child and family services in the state. If the assaulted patient has dementia or is an elder with cognitive issues and is therefore unable to consent, adult protective services should be contacted (8). There are also rules governing military sexual offenses. Remember when documenting these cases, whether using handwritten or electronic medical records, any and all information is subject to HIPAA.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What skills do you have that could best be used when caring for patients who have sexually assaulted?

- How would you, as the initial contact, approach an individual who has been sexually assaulted?

- What skills would you need to learn or improve when caring for a patient who has been sexually assaulted?

- Currently, do you feel capable of caring for a patient who has been sexually assaulted without judgment and with compassion?

- What documentation policies do you have at your facility regarding sexual assault victims?

Texas Forensic Law

The Texas government code 420.031 (9) describes the protocol that must be taken to develop and protect evidence collection in a sexual assault case. Since a major part of Texas is rural, the code was enacted to protect and care for patients and the collected evidence in areas where a SANE nurse is not available. In these cases, a medical forensic examiner may perform the exam and evidence collection.

A medical forensic examiner is described as any practitioner Medical Doctor, Registered Nurse, Nurse Practitioner, or Physician's Assistant who has undergone a minimum of 2 hours of training in forensic evidence collection. The law outlines requirements in the collection and preservation of evidence. In 2019, the code was amended to require written informed consent from the patient or guardian for release of the evidence and must be gained prior to the history and physical. Obtaining consent also carries important psychological implications after a sexual assault since the patient's right to consent was violated by the assaulter. Sexual assault examination teams should always be involved as early as possible.

Texas Forensic Law: Statute of Limitations

The statute of limitations for sexual assault cases can be defined as a deadline in which a person can report a sexual assault. The statute of limitations vary per state and the length of time for reporting can depend on whether the case is criminal or civil. Criminal cases are committed against the state and prosecuted by the state; civil cases occur between individuals/groups and are prosecuted by a civil court (i.e. family court or personal injury cases) (12). In Texas, the statute of limitations varies by age and whether the case is criminal or civil. The following are general statute of limitations regarding sexual assault in Texas (13)(14). The legal age of sexual consent in Texas is 17.

For adults, the statute of limitation is 10 years from the victim’s 18th birthday. As of 2019, victims of sexual assault can file a personal injury claim for injuries arising from childhood sexual abuse up to 30 years from the incident.

There is no statute of limitations if:

- During the investigation of the offense, biological matter (evidence) is collected, and the matter has not yet been subjected to forensic DNA testing

- Forensic DNA testing results show that the matter does not match the victim or any other person whose identity is readily ascertained

- Probable cause exists to believe that the defendant has committed the same or a similar sex offense against five more victims

- Continuous sexual abuse of young child or disabled individual occurs

- Indecency with a child occurs

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How would you handle a situation in which an adult patient wants to file a claim for a sexual assault that occurred 35 years ago?

- If your 16-year-old patient does not want to file a police report on her boyfriend who sexually assaulted her, how would you respond?

- In which situation would you involve social services?

- How often do you make reports to child or adult protective services?

- How do you become a medical forensic examiner?

- What is a statute of limitations in Texas?

- When is there no statute of limitations?

- What is the difference between criminal and civil cases?

Texas Forensic Law: Evidence

Sexual assault evidence can be found in several areas, including the crime scene, the patient's body, skin, hair, nails and clothing, and other items belonging to the patient (11). There is a specific kit used to collect this evidence. As described by RAINN, the kit is best known as a RAPE or Sexual Assault Evidence Kit (SAEK) and is inclusive of the items listed below (11):

- Bags and paper sheets to put on the floor and collect clothing or other evidence that may fall off the patient while undressing,

- A comb to collect evidence from hair

- Forms for documentation

- Envelopes and containers for the evidence

- Instructions on use of the kit

- Sampling materials and swabs

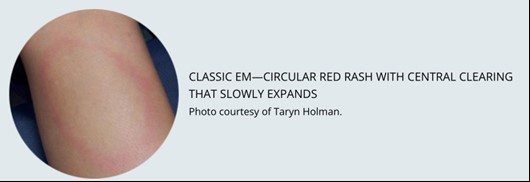

Types of evidence collected are usually skin samples, scrapings from fingernails, and oral, genital, and anal swabbing internal and external. Directions on how to collect this evidence are included in the kit. The forensic examiner can also use special types of photography to document internal injurie. (11). Personal cameras should never be used. Remember, it is the law that the patient consents to each part of the exam.