Course

Updates in Migraine Treatment

Course Highlights

- In this Updates in Migraine Treatment course, we will learn about the pathophysiology and epidemiology of migraines.

- You’ll also learn migraine symptoms and diagnosis criteria.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of treatment and management strategies for migraines.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 1

Course By:

R.E. Hengsterman, MSN, RN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

Migraines manifest in diverse forms, each distinguished by unique symptomology and presentation. The complex and often debilitating neurological disorder impacts over a billion people worldwide, leading to significant functional disabilities [1]. The word migraine comes from the term “hemikrania” (half-head) used by Galen of Pergamon. The Ebers Papyrus has an early description of migraine that dates to around 1500 BC in ancient Egypt [3]. The Hippocratic School of Medicine recorded observations of a visual aura preceding the headache and noted that vomiting could sometimes provide partial relief around 200 BC [1].

The economic burden of migraines is substantial. In a major financial services company of over 80,000 employees, estimated corporate expenses of employee absenteeism and related diminished productivity related to migraines amounted to almost 25 million per year [2]. The 2019 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study found that headache disorders ranked as the second most significant contributor to years lived with disability (YLD) [20].

Close to 91% of men and 96% of women experience headaches (one-year prevalence), with about 6% of men and 18% of women suffering from migraines per year [3]. Migraines are most common in individuals in their 20s and 30s and among those in lower socioeconomic groups. There is also an association between migraines and increased occurrences of anxiety symptoms and distress [3].

Definition

Migraine headaches (MH) are a complex episodic neurovascular event (neurological disorder) characterized by moderate-to-severe headache with associated features, most often unilateral with nausea and increased sensitivity to light and sound [6]. A migraine episode can last from hours to days characterized by recurrent and severe headache episodes accompanied by sensory disturbances, such as visual disturbances (auras), sensitivity to light and sound, and nausea [6].

Migraines are distinct from other types of headaches due to their associated symptoms, which can include:

- Aura: Some patients experience sensory disturbances (neurologic, gastrointestinal, and autonomic) known as aura before or during the migraine. These can include visual disturbances (flashes of light, blind spots), or tingling in the hands or face [7].

- Sensitivity to Light and Sound: During a migraine, there is often increased sensitivity to light (photophobia) and sound (phonophobia).

- Allodynia: Sensitivity to light touch due to a stimulus that under normal circumstances does not provoke pain [8].

- Nausea and Vomiting: Many individuals experience nausea and sometimes vomiting during a migraine.

- Duration: Migraine headaches can last for hours to days, impacting daily activities.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How might a more initiative-taking approach in migraine management and employee wellness programs reduce the costs of migraines while improving employee well-being?

- What strategies at a community or healthcare system level would better identify and support at-risk populations (young adults and lower socioeconomic groups)?

- Given that migraines present with unique symptoms, how might these features influence both the diagnosis and the approach to treatment for individuals experiencing migraine episodes?

Epidemiology

Prevalence

Migraines affect more than 10% of the global population, are most prevalent in individuals between the ages of 20 and 50, and are three times more prevalent in women than men [9]. According to a comprehensive survey conducted in the United States, 17.1% of women and 5.6% of men reported experiencing migraine symptoms [9]. Migraine headaches (MH) are the fourth highest cause of disability among women [10].

Onset

Migraines often first appear in childhood, adolescence, or early adulthood with many individuals experiencing their first migraine attack before the age of 30. The prevalence of migraines peaks in the late teenage years and early twenties [11]. In women in particular, the incidence of migraines begins to rise at the onset of menstruation and reaches its highest prevalence in the late 30s, then declines following menopause [10].

Genetics

There is a significant genetic component to migraines. Research indicates a heightened familial risk for common migraines, suggesting a polygenic (influenced by multiple genes) inheritance pattern. The heritability estimates for this condition range between 34% and 64% [12].

Socioeconomics

Migraines can have a significant socioeconomic impact and are a leading cause of disability worldwide resulting in missed workdays, reduced productivity, and increased healthcare costs. According to research, workplace effectiveness among individuals suffering from migraines is reduced by half during an attack. The decrease in productivity may be driven by intensity of the pain, numerous migraine-related symptoms, unpredictability of attacks, associated comorbidities, emotional burden, and societal stigma surrounding migraines [13].

Comorbidities

Migraine sufferers often have comorbid conditions including stroke, sub-clinical vascular brain lesions, coronary heart disease, hypertension, patent foramen ovale (PFO), psychiatric disorders (anxiety, depression), Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS), obesity, epilepsy, and asthma, which can complicate the management of migraines [14].

Demographics

Migraine prevalence can vary by geographic region and ethnicity. Some studies have suggested that migraines in African and Asian populations are lower when compared to those reported in European and North American populations [15]. In the United States, the frequency of migraine is highest among whites, with Blacks and Asian Americans following in prevalence [15]. Black patients experiencing headache disorders tend to report a greater number of headache days each month, more intense pain, and a lower quality of life compared to whites [17].

Migraine prevalence is higher among individuals with the lowest incomes or those living below the poverty level, as well as among the uninsured (17.1%) and those on Medicaid (26%), in comparison to those with private insurance (15.1%) [18]. Reports indicate that certain occupational groups, including healthcare workers, experience a higher incidence of migraines compared to the general population. Heavy workloads, emotional stress, and sleep disruptions for those arising from rotating night shifts can contribute to the increase [19].

Triggers

The triggers for migraines include hormonal changes, certain foods, alcohol, stress, travel, lack of sleep, weather, and environmental factors [16]. Identifying and managing these triggers is an important aspect of migraine care. No single migraine trigger affects all individuals. Research conducted by the National Migraine Centre revealed that while 79% of patients recognized certain factors they believed could trigger their migraines, the majority reported that it often takes a combination of several triggers to precipitate an attack [16].

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What role might hormonal fluctuations among women play in the onset and severity of migraine episodes, and how should this influence treatment strategies?

- How might understanding an individual’s family history of migraines alter the approach to prevention and management of their condition?

- What implications does geographic location and demographics have for public health strategies aimed at addressing the needs of diverse and underprivileged populations suffering from migraines?

- How can healthcare providers develop more personalized and holistic treatment plans that address multifaceted triggers for individual patients?

Pathophysiology / Etiology

Migraine headaches are a common neurological condition affecting a sizable portion of the population and the most prevalent neurological disorder across the globe [9]. Migraine headaches involve several key mechanisms including Neurovascular Theory, Trigeminovascular System Activation, Cortical Spreading Depression (CSD), neurotransmitter imbalance, hormonal influences, genetic factors, and environmental triggers [36].

Neurovascular Theory

Neurovascular Theory suggests the mediation of migraines occurs through the activation of neuronal pathway and changes within the Trigeminovascular system, shifting away from theory that vasodilation is the cause of migraines [21].

Trigeminovasclar System Activation

The Trigeminovascular System Activation involves the trigeminal nerve, a major cranial nerve responsible for sensation in the face and head. During a migraine, the trigeminal nerve becomes activated, releasing inflammatory substances and neuropeptides that lead to pain and inflammation in the surrounding blood vessels [22].

Cortical Spreading Depression

Cortical Spreading Depression (CSD) is a temporary wave of depolarization in the brain’s cortex, followed by suppression of neuronal activity. This process may trigger migraine auras, which are sensory disturbances that some individuals experience before or during a migraine [23]. A decrease in the neurotransmitter serotonin and low serotonin levels can lead to abnormal blood vessel dilation, increased head pain, and sensitivity [24].

Neurotransmitter Imbalance

The disruption of the balance of serotonin, glutamate, and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and decreased serotonin levels, triggers a cascade of events leading to pain and inflammation [24]. Glutamate, an excitatory neurotransmitter, becomes overactive, amplifying pain signals. CGRP, a potent vasodilator, further intensifies vascular changes [26].

Genetic Factors

Mutations in the genes CACNA1A, ATP1A2, SCN1A, and PRRT2 are known to be responsible for familial hemiplegic (motor weakness aura) migraine. The CACNA1A, ATP1A2, and SCN1A genes code for proteins essential for the movement of ions across cell membranes [25]. This ion transport is crucial for the proper communication between neurons in the brain and throughout the nervous system, playing a significant role in normal neurological function [25].

Hormonal Influences

Hormonal fluctuations in women can influence migraine onset which often begin following menarche and tend to improve during pregnancy and after menopause [27]. Estrogen levels influence changes in migraine patterns, which affect cellular excitability and the cerebral blood vessels [27]. The use of external hormones can exacerbate migraines and may heighten the risk of vascular diseases in women prone to migraines.

A migraine with aura is a recognized risk factor for conditions such as stroke, heart disease, and vascular mortality [27]. Research indicates that when women who experience migraines take combined oral contraceptives, their risk for ischemic stroke may increase. Therefore, it is advisable for healthcare professionals to exercise caution when prescribing combined oral contraceptives to women who suffer from migraines with aura [27].

Environmental Triggers

Individuals with migraines report environmental factors as a trigger including changes in barometric pressure, exposure to bright sunlight or flickering lights, air quality, numerous odors, indoor spaces, and workplaces are also known to play a role in triggering migraines. [28].

Physical, emotional, and psychological stress are significant migraine triggers, disturbing the brain’s intricate equilibrium [37]. The neuronal and hormonal alterations linked to stress, along with the response to perceived psychological stress have various connections to migraine. Stress can not only trigger the initial onset of migraines (incidence) but also serves as a risk factor for the occurrence of migraine attacks [29] [37].

Certain foods and drinks, including chocolate, caffeine, milk, cheese, and alcoholic beverages can be triggers for migraine attacks [30]. In their 2013 review, Hoffmann and Recober observed that dietary factors are among the most cited triggers for migraines. These often encompass items like chocolate, cheese, nuts, citrus fruits, processed meats, monosodium glutamate, aspartame, fatty foods, coffee, and alcohol [30].

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How might emerging research in pathophysiology influence the development of new therapeutic strategies for migraine treatment?

- Considering the genetic factors involved in migraines, how could providers personalize medicine approaches to tailor treatments for individuals with a family history of migraines?

- Considering environmental and dietary triggers, what strategies could be employed in public health education to help individuals identify and manage their migraine?

- How might knowledge of hormonal fluctuations in women influence the approach to migraine management in various stages of a woman’s life, including decisions regarding the use of hormonal contraceptives?

The Stages of Migraine Headaches

Migraines often progress through four distinct phases, each phase with a unique set of symptoms. The three phases are premonitory, headache, and postdrome.

Premonitory Phase

Premonitory phase can occur days or hours before the headache, manifesting as subtle signs such as fatigue, irritability, neck stiffness, food cravings, mood changes, excessive yawning, fluid retention, or increased urination [31]. In the aura phase, some individuals experience visual disturbances like shimmering zigzags or blind spots, tingling sensations, speech difficulties, or temporary weakness, which signal the approaching migraine [31].

Headache Phase

The headache phase occurs with intense, pulsating pain accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and sensitivity to light, sound, and smells.

Postdrome Phase

In the postdrome phase, lingering symptoms include fatigue, yawning, cravings for certain foods, frequent urination, confusion, and emotional fluctuations which can persist for hours or days [31].

Primary Migraine Types

Migraines come in various forms, each distinguished by unique symptoms and features. The following are examples of migraine types.

Classic Migraines

Classic migraines are known for their aura phase, often involving visual disturbances, which precedes the headache [32]. Visual disturbances and other neurological symptoms that manifest 10 to 60 minutes before the headache begins and subside within an hour define migraine with aura, known as classic migraine [32]. During this aura phase, individuals may experience temporary vision loss or even have an aura without accompanying headache pain, which can occur at any time. Classic aural symptoms include difficulties in speaking, abnormal sensations, numbness, muscle weakness on one side of the body, a tingling feeling in the hands or face, and confusion [33]. Prior to the onset of headache there may also be nausea, a loss of appetite, and heightened sensitivity to light, sound, or noise [6] [7].

Symptoms of classic migraines include moderate to severe throbbing pain on one side of the head accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and sensitivity to light and sound.

Common Migraines

In contrast, common migraines occur without aura, and are more prevalent [38]. Common migraines strike without preceding warning signs. The pain often concentrates on one side of the head. Accompanying symptoms can include nausea, confusion, blurred vision, mood changes, fatigue, and an increased sensitivity to light, sound, or noise [38].

Hemiplegic Migraines

Hemiplegic migraines are notable for causing temporary weakness or paralysis on one side of the body [25].

Vestibular Migraines

Vestibular migraines present with symptoms of dizziness and vertigo, and balance issues, often without substantial head pain [38] [39]. Frequency defines a chronic migraine with headaches occurring on 15 or more days per month for at least three months [40].

Abdominal Migraines

Abdominal migraines often affect young children, presenting as moderate to severe abdominal pain centered around the midsection, which can last from one to 72 hours, often with minimal or no headache [33]. Accompanying symptoms include nausea, vomiting, and a loss of appetite.

Basilar-type Migraines

Basilar-type migraines, also occurring in children and adolescents, are more common in teenage girls and may correlate with their menstrual cycle [41]. Symptoms encompass partial or total vision loss or double vision, dizziness, balance issues, poor muscle coordination, slurred speech, ringing in the ears, and fainting, with throbbing pain that emerges on both sides of the back of the head [41].

Retinal Migraines

Retinal migraines involve episodes of visual loss or disturbances in one eye, often accompanying migraine headaches [34].

Status Migrainosus

Status migrainosus is a rare and severe form of acute migraine, characterized by debilitating pain and nausea lasting over 72 hours. The severity of this condition is such that hospitalization may be necessary for those affected [33].

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How do manifestations of different migraine types influence the approach to diagnosis?

- What preventive measures and lifestyle modifications could be particularly effective for individuals experiencing migraines with auras?

- How might understanding symptoms of less common migraine types guide the development of specialized management and treatment plans?

- Given the severe nature and potential complications of rare migraine types, what emergency protocols should be in place to adequately address these cases?

Diagnosis

The International Headache Society (IHS) has established diagnostic criteria for migraines [44]. To meet the criteria for a migraine diagnosis, a patient must have experienced at least five attacks that meet specific criteria [42] [44]. These attacks should last between 4 to 72 hours when untreated or treated without success.

The characteristics of the headache should include at least two of the following four traits [42] [44]:

- Unilateral location

- A pulsating quality

- Moderate or severe pain intensity

- Aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activities like walking or climbing stairs

During the headache, the patient must experience one or more of the following non-headache symptoms [42] [44]:

- Nausea and/or vomiting

- Sensitivity to light (photophobia) and sound (phonophobia)

An alternative diagnosis should not explain the symptoms according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd Edition (ICHD-3) [44].

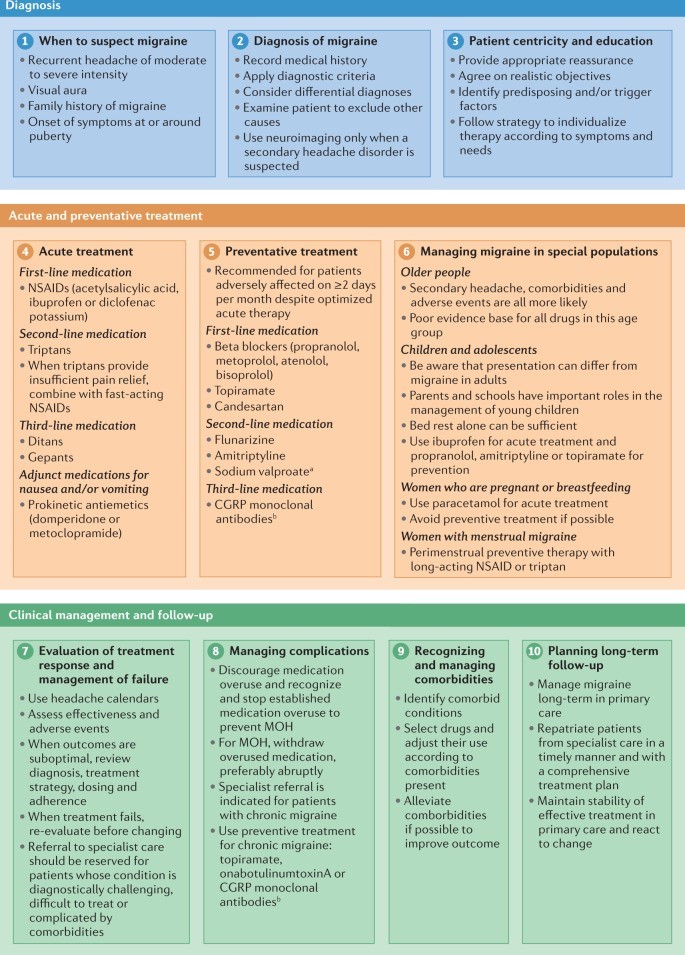

Figure 1. Ten-step approach to the diagnosis and management of migraine [42]

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Based on the International Headache Society for Migraines diagnostic criteria, how might the requirement of experiencing at least five attacks impact the early detection and treatment of migraines in individuals who may have fewer but severe episodes?

- Considering diagnostic criteria set by the International Headache Society for Migraines, including the nature and duration of attacks and associated symptoms, how might these criteria influence the development of personalized treatment plans, for patients whose migraine patterns do not align with these standards?

Treatment

The relief and management of acute migraine attacks involve a combination of treatments and strategies. The following are treatment options in the management of migraines.

Pain Relievers

Over the counter (OTC) pain relievers like ibuprofen, aspirin, or naproxen sodium can be effective for mild to moderate migraines [45] [46]. For more severe cases, prescription medications such as triptans (sumatriptan, rizatriptan) narrow blood vessels and reduce brain inflammation. Ondansetron and combination medications that include a triptan and an anti-nausea agent, provide more comprehensive relief [45] [46].

Preventive Measures

Preventive measures include beta-blockers, anticonvulsants, and tricyclic antidepressants to reduce the frequency and severity of attacks [45]. Newer treatments like CGRP monoclonal antibodies (erenumab, fremanezumab) and Botox injections are adjunct therapies in the prevention of migraines in chronic cases [46] [47].

Lifestyle Modifications

Lifestyle modifications play a crucial role, involving identifying and avoiding personal triggers, maintaining regular sleep patterns, dietary changes, staying hydrated, and managing stress through relaxation techniques, mindfulness, or meditation [48].

Non-Pharmacological Approaches

Non-pharmacological approaches including biofeedback, cognitive-behavioral therapy, acupuncture, and the use of medical devices (transcranial magnetic stimulators) can contribute to managing migraines [49].

Migraine Medications

- Dihydroergotamine, available under the brand names Migranal and Trudhesa, is a nasal spray or injectable medication. It is most beneficial when used early in the onset of migraine symptoms, especially for migraines lasting over 24 hours [51]. However, it can exacerbate migraine-associated nausea and vomiting for individuals with coronary artery disease, high blood pressure, or kidney or liver disease [51].

- Lasmiditan, sold as Reyvow, is a newer oral medication for treating migraines with or without aura [52]. In clinical trials, Lasmiditan has shown effectiveness in reducing headache pain though it may induce drowsiness and dizziness; thus, patients should not drive or operate machinery for at least eight hours after consumption [52].

- Oral Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) Antagonists, also known as gepants, including Ubrogepant (Ubrelvy) and Rimegepant (Nurtec ODT), have approval for adult migraine treatment [53]. Clinical studies have demonstrated their superiority over placebo in pain relief within two hours of intake and effectiveness in addressing other migraine symptoms like nausea and sensitivity to light and sound [53]. Common side effects are dry mouth, nausea, and excessive sleepiness. Ubrogepant and rimegepant are contraindicated in combination with strong CYP3A4 inhibitors, which include certain cancer medications [54].

- Zavegepant (Zayzpret), a groundbreaking nasal spray and the first of its kind as a calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonist, was designed for the acute treatment of migraines in adults [55]. This medication was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in March of 2023.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What factors should guide a healthcare provider in choosing between an OTC and prescription pain reliever for migraines?

- How can healthcare providers determine the most suitable preventive strategy for individual patients?

- What criteria can healthcare providers use to evaluate the effectiveness of non-pharmacological approaches migraine management, such as biofeedback, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and acupuncture?

- What are the potential benefits and limitations of new treatments like zavegepant nasal spray therapy compared to existing treatments?

Case Study

Patient Presentation

- Presentation: Jordan Smith, a 32-year-old female software developer, arrives at your clinic complaining of recurrent severe throbbing, pulsating headache on the right side of her head, accompanied by nausea, sensitivity to light and sound, fatigue, and occasional vomiting. She reports sensitivity to light and sound, seeking a dark, quiet room during incidents and occasionally has visual disturbances (aura) preceding the headache, described as flashing lights or zigzag lines.

- Medical History: No significant past medical history, non-smoker, occasional alcohol consumption. Family history of migraines in mother.

- Lifestyle Factors:

- High-stress job with long hours in front of a computer.

- Irregular meal patterns, often skipping breakfast.

- Moderate coffee consumption, about 2-3 cups a day.

- Inconsistent sleep schedule due to work demands.

Clinical Examination and Investigations

- Physical Examination: Normal, no neurological deficits.

- Blood Tests: Complete blood count, (CBC), electrolytes, thyroid function tests, all within normal limits.

- Neuroimaging: Not performed as clinical presentation is consistent with migraines without alarming features.

Diagnosis

Based on the history and clinical presentation, Ms. Smith receives a diagnosis of Migraine with Aura.

Management Plan

- Education on migraine triggers and stress management techniques

- Encouraging regular meals and adequate hydration

- Advising regular sleep patterns and reduction of caffeine intake

- Recommending regular exercise

Medication Management

- Acute Treatment: Ibuprofen 400 mg or a combination analgesic containing acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine. Triptans as needed at onset of headache [4].

- Preventive Treatment: Consider a beta-blocker or amitriptyline if the frequency of migraines increases [5].

Follow-up and Monitoring

- Scheduled follow-up in four weeks to evaluate response to lifestyle changes and medication.

- Keeping a headache diary to identify potential triggers and patterns.

Prognosis

Although migraines are a long-term health issue, Ms. Smith can anticipate a considerable decrease in both the frequency and intensity of her migraine episodes by adopting appropriate lifestyle changes, managing stress, and utilizing the correct medication regimen. It is essential to maintain regular check-ins with her provider to track her progress and make any necessary adjustments to her treatment plan.

- How might Ms. Smith’s lifestyle factors, high-stress job, and irregular meal patterns contribute to the frequency and severity of her migraine episodes?

- What specific changes could she implement to potentially alleviate these triggers?

- Considering the effectiveness of both medication and lifestyle adjustments in managing migraines, what criteria could evaluate the success of Ms. Smith’s treatment plan at her follow-up appointment?

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How might the comprehensive approach to managing Ms. Smith’s migraine serve as a model for personalized migraine treatment plans?

- What are the factors to consider when tailoring this approach to individual patients with varying migraine presentations and lifestyles?

- How might the understanding of the headache stages assist in developing more effective strategies for early intervention and post-attack migraine care?

Conclusion

The case study of Jordan Smith, a 32-year-old female software developer, highlights typical migraine presentation, involving severe throbbing headaches with aura, light and sound sensitivity, and nausea, leading to a diagnosis of Migraine with Aura. Management involves education, lifestyle adjustments, and medication like ibuprofen or triptans for acute treatment, and the use of beta-blockers or amitriptyline for prevention.

The International Headache Society provides specific diagnostic criteria, while treatment encompasses both pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches, emphasizing the importance of lifestyle modifications and regular monitoring. The recent addition of novel treatments like zavegepant (Zavzpret), the first CGRP receptor antagonist nasal spray approved by the FDA, offers a promising new option for acute management [55].

The use of oral CGRP antagonists, such as Ubrogepant (Ubrelvy) and Rimegepant (Nurtec ODT), has shown effectiveness in providing pain relief and addressing other migraine symptoms like nausea and sensitivity to light and sound [53]. For cases requiring more specific interventions, dihydroergotamine, available as a nasal spray or injectable medication, can be beneficial, especially for migraines lasting over 24 hours [51]. Lasmiditan, an oral medication for migraines with or without aura, has also been effective in clinical trials, though it requires caution due to its sedative effects [52].

Preventive measures, including beta-blockers, anticonvulsants, and tricyclic antidepressants, are essential in reducing the frequency of migraines [45]. Moreover, lifestyle modifications, such as managing stress, maintaining regular sleep patterns, and identifying personal triggers, are crucial components of the treatment strategy [48].

References + Disclaimer

- Gupta, J., & Gaurkar, S. (2022). Migraine: an underestimated neurological condition affecting billions. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.28347

- Burton, W. N., Conti, D., Chen, C., Schultz, A. B., & Edington, D. W. (2002). The economic burden of lost productivity due to migraine headache: a specific worksite analysis. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 44(6), 523–529. https://doi.org/10.1097/00043764-200206000-00013

- Silberstein, S. D., & Lipton, R. B. (1993). Epidemiology of migraine. Neuroepidemiology, 12(3), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1159/000110317

- Gilmore, B., & Michael, M. (2011, February 1). Treatment of acute migraine headache

- AAFP. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2011/0201/p271.htm

- Kumar, A. (2023, August 28). Migraine prophylaxis. Stat Pearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507873/

- Migraine headache. (2023, January 1). PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32809622/

- Kikkeri, N. S. (2022, December 6). Migraine with aura. Stat Pearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554611/

- He, Y. (2023, September 4). Allodynia. Stat Pearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537129/

- Walter, K. (2022). What is migraine? JAMA, 327(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.21857

- Pavlović, J. (2020). The impact of midlife on migraine in women: summary of current views. Women’s Midlife Health, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-020-00059-8

- Colon, É., Ludwick, A., Wilcox, S. L., Youssef, A. M., Danehy, A., Fair, D. A., Lebel, A., Burstein, R., Becerra, L., & Borsook, D. (2019). Migraine in the Young Brain: Adolescents vs. Young Adults. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2019.00087

- Bron, C., Sutherland, H. G., & Griffiths, L. R. (2021). Exploring the hereditary nature of migraine. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, Volume 17, 1183–1194. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.s282562

- De Dhaem, O. B., & Sakai, F. (2022). Migraine in the workplace. eNeurologicalSci, 27, 100408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensci.2022.100408

- Wang, S. J., Chen, P. K., & Fuh, J. L. (2010). Comorbidities of migraine. Frontiers in Neurology, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2010.00016

- Stewart, W. F., Lipton, R. B., & sLiberman, J. N. (1996). Variation in migraine prevalence by race. Neurology, 47(1), 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.47.1.52

- Migraine triggers – National Migraine Centre. (2023, July 31). National Migraine Centre. https://www.nationalmigrainecentre.org.uk/understanding-migraine/factsheets-and-resources/migraine-triggers/

- Kiarashi, J., VanderPluym, J., Szperka, C. L., Turner, S. B., Minen, M., Broner, S. W., Ross, A. C., Wagstaff, A. E., Anto, M., Marzouk, M., Monteith, T., Rosen, N., Manrriquez, S. L., Seng, E. K., Finkel, A. G., & Charleston, L. (2021). Factors associated with, and mitigation strategies for, health care disparities faced by patients with headache disorders. Neurology, 97(6), 280–289. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000012261

- Dodick DW, Loder EW, Manack Adams A, et al. Assessing barriers to chronic migraine consultation, diagnosis, and treatment: results from the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) study. Headache. 2016;56(5):821-834.

- Kuo W.Y., Huang C.C., Weng S.F., Lin H.J., Su S.B., Wang J.J., Guo H.R., Hsu C.C. Higher migraine risk in healthcare professionals than in general population: A nationwide population-based cohort study in Taiwan. J. Headache Pain. 2015; 16:102. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0585-6

- Hisham, S., Manzour, A. F., Fouad, M., Amin, R. M., Hatata, H. A., & Marzouk, D. (2023). Effectiveness of integrated education and relaxation program on migraine-related disability: a randomized controlled trial. The Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery, 59(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-023-00745-0

- Jacobs, B. A., & Dussor, G. (2016). Neurovascular contributions to migraine: Moving beyond vasodilation. Neuroscience, 338, 130–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.06.012

- Ashina, M., Hansen, J. M., Phu, T., Melo-Carrillo, A., Burstein, R., & Moskowitz, M. A. (2019). Migraine and the trigeminovascular system—40 years and counting. Lancet Neurology, 18(8), 795–804. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(19)30185-1

- Charles, A., & Baca, S. M. (2013). Cortical spreading depression and migraine. Nature Reviews Neurology, 9(11), 637–644. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2013.192

- Aggarwal, M., Puri, V., & Puri, S. (2012). Serotonin and CGRP in migraine. Annals of Neurosciences, 19(2). https://doi.org/10.5214/ans.0972.7531.12190210

- Kumar, A. (2023, July 4). Hemiplegic migraine. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513302/

- Iyengar, S., Ossipov, M. H., & Johnson, K. W. (2017). The role of calcitonin gene–related peptide in peripheral and central pain mechanisms including migraine. PAIN, 158(4), 543–559. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000831

- Sacco, S., Ricci, S., Degan, D., & Carolei, A. (2012). Migraine in women: the role of hormones and their impact on vascular diseases. Journal of Headache and Pain, 13(3), 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-012-0424-y

- Friedman, D. I., & Dye, T. D. (2009). Migraine and the environment. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 49(6), 941–952. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01443.x

- Stubberud, A., Buse, D. C., Kristoffersen, E. S., Linde, M., & Tronvik, E. (2021). Is there a causal relationship between stress and migraine? Current evidence and implications for management. Journal of Headache and Pain, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-021-01369-6

- Hindiyeh, N., Zhang, N., Farrar, M., Banerjee, P., Lombard, L., & Aurora, S. K. (2020). The Role of Diet and Nutrition in Migraine Triggers and Treatment: A Systematic Literature review. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 60(7), 1300–1316. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13836

- American Migraine Foundation. (2022, December 6). The Timeline of a migraine attack | American Migraine Foundation. https://americanmigrainefoundation.org/resource-library/timeline-migraine-attack/

- Goadsby, P., Holland, P. R., Martins-Oliveira, M., Hoffmann, J., Schankin, C., & Akerman, S. (2017). Pathophysiology of Migraine: a disorder of sensory processing. Physiological Reviews, 97(2), 553–622. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00034.2015

- Migraine. (2023). National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/migraine

- Khalili, Y. A. (2023, June 26). Retinal migraine headache. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507725/

- Migraine diagnosis. (2023). Science of Migraine. https://www.scienceofmigraine.com/management/migraine-diagnosis-criteria

- Pleș, H., Florian, I., Timiș, T. L., Covache-Busuioc, R., Glavan, L., Dumitrascu, D., Popa, A. M., Bordeianu, A., & Ciurea, A. V. (2023). Migraine: Advances in the pathogenesis and treatment. Neurology International, 15(3), 1052–1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint15030067

- Borsook, D., Maleki, N., Becerra, L., & McEwen, B. S. (2012). Understanding Migraine through the Lens of Maladaptive Stress Responses: A Model Disease of Allostatic Load. Neuron, 73(2), 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.01.001

- Amiri, P., Kazeminasab, S., Nejadghaderi, S. A., Mohammadinasab, R., Pourfathi, H., Araj‐Khodaei, M., Sullman, M. J. M., Kolahi, A., & Safiri, S. (2022). Migraine: A review on its history, global epidemiology, risk factors, and comorbidities. Frontiers in Neurology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.800605

- Smyth, D., Britton, Z., Murdin, L., Arshad, Q., & Kaski, D. (2022). Vestibular migraine treatment: a comprehensive practical review. Brain, 145(11), 3741–3754. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awac264

- Murphy, C. (2023, July 31). Chronic headaches. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559083/

- Kadian, R. (2023, June 26). Basilar migraine. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507878/

- Eigenbrodt, A. K., Ashina, H., Khan, S., Diener, H., Mitsikostas, D. D., Sinclair, A. J., Pozo‐Rosich, P., Martelletti, P., Ducros, A., Lantéri-Minet, M., Braschinsky, M., Del Río, M. S., Daniel, O., Özge, A., Mammadbayli, A. K., Arons, M., Skorobogatykh, K., Романенко, В. Н., Terwindt, G. M., . . . Ashina, M. (2021). Diagnosis and management of migraine in ten steps. Nature Reviews Neurology, 17(8), 501–514. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-021-00509-5

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018; 38:1–211.

- Guidelines /ICHD – International Headache Society. (2023, October 27). International Headache Society. https://ihs-headache.org/en/resources/guidelines/

- Mayans, L., & Walling, A. (2018, February 15). Acute migraine headache: Treatment Strategies. AAFP. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2018/0215/p243.html

- Ong, J. J. Y., & De Felice, M. (2017). Migraine treatment: Current acute medications and their potential mechanisms of action. Neurotherapeutics, 15(2), 274–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-017-0592-1

- Quintana, S., Russo, M., Manzoni, G. C., & Torelli, P. (2022). Comparison study between erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab in the preventive treatment of high frequency episodic migraine and chronic migraine. Neurological Sciences, 43(9), 5757–5758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06254-x

- Agbétou, M., Adoukonou, T., & Adoukonou, T. (2022). Lifestyle modifications for migraine management. Frontiers in Neurology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.719467

- Puledda, F., & Shields, K. (2018). Non-Pharmacological approaches for migraine. Neurotherapeutics, 15(2), 336–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-018-0623-6

- Meara, K. (2023, August 7). Pfizer’s new migraine treatment now available in US pharmacies: What you need to know. Drug Topics. https://www.drugtopics.com/view/pfizer-s-new-migraine-treatment-now-available-in-us-pharmacies-what-you-need-to-know

- American Headache Society. (2022, December 9). Dihydroergotamine mesylate nasal Spray FDA approved for migraine Treatment | AHS. https://americanheadachesociety.org/news/dihydroergotamine-mesylate-nasal-spray-receives-fda-approval-for-the-acute-treatment-of-migraine-in-adults/

- Berger, A. A. (2020, October 10). Lasmiditan for the treatment of migraines with or without aura in adults. PubMed Central (PMC). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7901123/

- Rissardo, J. P., & Caprara, A. L. F. (2022). GePants for Acute and Preventive Migraine Treatment: A Narrative review. Brain Sciences, 12(12), 1612. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12121612

- Migraine – Diagnosis and treatment – Mayo Clinic. (2023, July 7). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/migraine-headache/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20360207

- Dhillon, S. (2023). Zavegepant: First approval. Drugs, 83(9), 825–831. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-023-01885-6

Resources:

American Migraine Foundation: https://americanmigrainefoundation.org/

National Headache Foundation: https://headaches.org/

World Headache Organization: https://ihs-headache.org/en/

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate