Course

Ventilator Weaning

Course Highlights

- In this Ventilator Weaning course, we will learn about the ventilator modes used in weaning mechanical ventilation.

- You’ll also learn the risk factors for failure to wean ventilation.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of the appropriate assessments during the weaning process.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 1

Course By:

Keith Wemple, BSN, RN, CCRN, CMC

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

Mechanical ventilation is an important part of the treatment of many clients in the intensive care unit. It is used to assume control of the life-sustaining process of breathing until a client’s critical condition can be reversed. But when a person does recover, how do we get them from full life support to breathing freely again? How do we know a person is even ready to begin the process of being liberated from the ventilator? And how do we help them reach that goal? This course will answer those questions and give you a deeper insight into everything that goes into weaning a person from the ventilator.

Ventilator Review

Let’s start with a basic ventilator review. A mechanical ventilator is a device that can perform the life-sustaining process of respiration – namely, bringing oxygen into the body and removing carbon dioxide (CO2). This requires the person to be intubated or have a tracheostomy. The ventilator allows the provider to control the respiratory rate, the size of each breath, oxygen concentration and positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP). These variables are adjusted to treat the client’s condition and maintain adequate delivery of oxygen and removal of CO2.

Ventilators generally have three basic modes: controlled mandatory ventilation (CMV), synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) and pressure control. Controlled mandatory ventilation (CMV) is what it sounds like: the breathing is entirely controlled by the provider and provides breaths of a mandatory size and rate to the client. This mode offers the most control over respiration, and is therefore generally the starting mode when attempting to treat a client. SIMV is a little more complex. This mode allows the client to trigger a breath, while still controlling the size of the breath and having some sort of set rate to ensure adequate ventilation. Pressure control is a mode that only provides pressure support to the client, with an emergency backup mode should they fail to breathe. This mode requires the most work from the client, and offers the least control by the provider.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What strategies do you typically see used to wean a client from the ventilator?

- What ventilator modes do you typically see where you work?

- How are modes adjusted when weaning from the ventilator?

- How is this affected by pressure-controlled versus volume-controlled ventilation?

Weaning Criteria

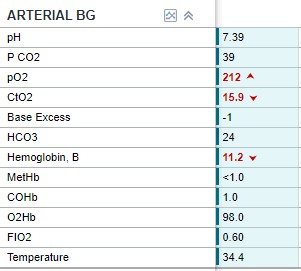

Before we go to in depth on the how-to of weaning the ventilator, let’s talk about how we decide someone is ready for weaning. Criteria are usually based on an improvement in the cause of respiratory failure that required the use of mechanical ventilation to begin with. This isn’t very easy to assess with one simple test, and usually requires a combination of assessments. Common assessments for an improvement in the condition are chest x-ray, arterial blood gasses (ABGs), vital signs and measuring P/F ratio. The P/F ratio is the PaO2 to FiO2 ratio. To calculate this ratio, you take the client’s PaO2 from their ABG and divide it by the client’s FiO2. A P/F ratio >150 is typically used as an acceptable level for weaning ventilation (1). ABGs are used to assess a client’s oxygenation, pH and CO2 levels. A pH >7.25 is another criterion that a client may be ready for weaning off the ventilator (1). Hemodynamic stability is another important criterion. A client may be stabilized from a respiratory standpoint, but if they are still very hemodynamically unstable it may be unwise to try and wean them off the ventilator.

Outside of these numerical criteria, a client must also be able to initiate breaths on their own. This may sound like a no-brainer, but a client with great labs who cannot trigger their own breaths cannot be extubated. To ensure the client is able to breathe on their own, neurologic assessments may be necessary. It is also important to ensure that any paralytic used for intubation or during mechanical ventilation has sufficiently worn off or has been reversed.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What criteria do providers at your facility use for starting the weaning process?

- How would you define “hemodynamic stability”?

- Calculate the P/F ratio for the following ABG and determine if this client is ready to start weaning off the ventilator.

Prolonged Weaning

Aside from the criteria for readiness to start the weaning process there are also certain risk factors we should look at. Research has found a number of risk factors that make clients more likely to require prolonged weaning or to outright fail ventilator weaning. Prolonged weaning is generally defined as requiring mechanical ventilation greater than 7 days or failure of 3 or more spontaneous breathing trials (3).

A higher age and more comorbidities unsurprisingly increased the risk for prolonged weaning from the ventilator (3). Specific comorbidities that increased the length of weaning are previous stroke, COPD, poor cardiac function and renal impairment (3). Certain labs were associated with prolonged weaning as well, including low platelets, elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN), elevated creatinine, low serum albumin, elevated blood glucose levels or hypernatremia (3). Several of these reflect poor renal function, which we already established is a risk factor. Low platelets and low albumin suggest liver dysfunction, which may play a role in the whole picture of the client’s readiness to wean off the ventilator.

Higher levels of FiO2 and PEEP as well as lower P/F ratios are also risk factors for prolonged weaning (3). To boil this down, if the client is requiring higher levels of ventilator support and has failure of an organ other than the lungs, they likely will require prolonged ventilation weaning.

Research has shown that clients who require prolonged weaning benefit from using a protocolized approach to ventilator weaning (10). There are a number of different ventilator liberation protocols, and none has emerged as superior to the others, so it is really up to provider preference (10). Early mobilization is a tool that can help clients wean from the ventilator successfully (10). Chest physiotherapy is another intervention that can help assist weaning in clients that have a prolonged weaning (8).

Weaning Failure

Weaning failure is defined as failure to wean within 28 days, reintubation within 72 hours of weaning off the ventilator, transfer to a specialized unit for prolonged mechanical ventilation or death before successful weaning (3). Risk factors for weaning failure include: higher age, female gender, extremes of BMI (high and low), previous home mechanical ventilation, and certain diseases (3). Pre-existing COPD, neuromuscular disease, restrictive lung disease and arterial hypertension all increased the likelihood of weaning failure (3). The cause for mechanical ventilation in the first place is also an important factor, although the research doesn’t point to any specific conditions. Essentially, the sicker they are when starting mechanical ventilation, the more likely they are to fail weaning off the ventilator. You may have noticed there is some overlap between risk factors for prolonged weaning and failure to wean – namely, COPD, higher age and poor functional status.

One interesting assessment for weaning failure is the use of ultrasound. Studies have found that using ultrasound to assess the client’s diaphragm thickness and amount of diaphragmatic excursion can predict their likelihood to be successfully weaned from the ventilator (9). Clients with thicker diaphragms and with more excursion (diaphragm movement) are more likely to successfully wean from the ventilator (9). If the client does fail to wean from the ventilator and prolonged ventilation is required, a tracheostomy may be necessary (5). Tracheostomy can be used as a tool to assist in prolonged weaning, or as a means to maintain mechanical ventilation indefinitely (5).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Have you noticed a pattern in the clients who require prolonged ventilation?

- If the client has failure of one of these other organ systems, how might treatment change?

- What causes for mechanical ventilation have you noticed are more likely to fail weaning?

- Are there any conditions or signs you think are missing from the list of risk factors?

Weaning Process

The first step of the weaning process is assessing the client’s readiness to begin weaning. We have already covered that, so let’s look at the next step. Step two of the weaning process is to begin withdrawing ventilator support to see if the client can perform some of the work of breathing on their own. This typically involves changing through the different ventilator modes. The usual progression is CMV to SIMV and finally pressure control (1). This follows a progression of less ventilator support and more respiratory effort by the client.

In SIMV and pressure control modes, there is a setting called the client trigger. The client trigger is the minimum amount of pressure change the client must create in order for the ventilator to deliver a breath (2). If the trigger is set low, it is easier for the client to initiate breaths. This generally means that the client will do more of the breathing on their own without having to work too hard. An important part of the weaning process is slowly increasing this trigger so that the client is generating more effort and requiring less support from the ventilator to take large enough breaths (2). This is a process called inspiratory muscle training. Research shows that training clients’ trigger up to 20% or more of their mean inspiratory pressure greatly improves ventilator weaning success (2).

Once a client is able to take 100% spontaneous breaths at a sufficient trigger the next step is to reduce the amount of pressure support the ventilator offers. Pressure support adds inspiratory pressure to the client’s breath to ensure they take a large enough breath (2). Generally, as the client’s trigger increases, they will produce more effort and less pressure support is needed (2). Depending who you ask, a pressure support of less than 5-8 cm H2O is acceptably low to move on to the next step (1). The rapid shallow breathing index (RSBI) is a more recent tool that has been used to assess client’s readiness for ventilator weaning and extubation. The rapid shallow breathing index is calculated by taking the client’s respiratory rate and dividing it by their tidal volume in liters (1). A value of less than 105 breaths/min/L indicates a high likelihood of success.

For neonates, the process may be slightly different if the client is on high-frequency ventilation. While it is possible to wean off ventilator support in high-frequency ventilation, it is more common and successful to first wean to SIMV (7). Neonates especially benefit from steroids as part of their treatment during ventilator weaning (7). Outside of the considerations for high-frequency ventilation, weaning ventilation for pediatrics is similar to adults (6). One difference is that research supports some form of non-invasive ventilation along with cough-assist strategies post-extubation (6).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- A client is mechanically ventilated and breathing spontaneously on SIMV. They are breathing at a rate of 18 and taking tidal volumes of about 300mL. What is their RSBI?

- The ventilator shows a mean airway pressure of 18 cm H2O. What pressure trigger should you target?

- In your practice how long are clients kept on each mode before advancing to the next in the weaning process?

Spontaneous Breathing Trial

Once the trigger is sufficiently high and the pressure support is sufficiently low, a spontaneous breathing trial can be performed. In order to give the client the best chance of succeeding during the spontaneous breathing trial, sedation should be minimized or turned off, narcotics should be held and any neuromuscular relaxers should be held or reversed (1). Sedatives commonly used to help clients tolerate intubation and mechanical ventilation also depress respiratory drive. If these medications are still in their system the client may fail the breathing trial despite having adequate underlying respiratory function.

Similarly, many of these clients require opioids which also depress respiratory function, especially when combined with sedatives (4). Neuromuscular blockers will prevent the diaphragm and other inspiratory muscle from moving, so they must be out of the client’s system prior to initiating a spontaneous breathing trial (1).

A spontaneous breathing trial can be performed by removing the client from the ventilator onto a T-piece which provides oxygen but no ventilatory support (1). Some providers will perform a spontaneous breathing trial by minimizing the ventilator support and placing the client on a spontaneous mode, such as pressure control. Adequately low levels of support are considered pressure support 5-8 cm H2O, PEEP ≤5 cm H2O, FiO2 ≤0.4-0.5 (1).

During the spontaneous breathing trial, the client is assessed closely for signs of weaning failure. Signs of weaning failure include a respiratory rate >35 breaths per minute, persistently low SpO2, hemodynamic instability, increased accessory muscle activity and significant change in mental status (1). If these signs develop the client will need to be put back on appropriate ventilator support. If the client tolerates the spontaneous breathing trial for >30 minutes they can be considered for extubation (1).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What sedatives do you typically use for clients on mechanical ventilation?

- How long does it take for these medications to be cleared from the client’s system?

Extubation

When a client meets all the criteria for extubation and passes their spontaneous breathing trial they can be extubated. During extubation be sure to have an oxygen source, a bag and mask for hand ventilation and suction nearby (4). It is also wise to have a plan for what to do if the client fails extubation, whether that is reintubation or initiating bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP). During and after extubation carefully assess the client’s respiratory rate, respiratory effort, SpO2 and mental status (4). Increased respiratory rate or effort could be a sign of failure of the weaning process. A significant decrease in mental status could also necessitate replacing the advanced airway. If changes do occur an ABG may be warranted (1).

This process is slightly different if the client has a tracheostomy. If the client with a tracheostomy meets criteria to be weaned off the ventilator, then the ventilator circuit is removed and replaced with an oxygen delivery source such as a trach collar (1). The monitoring after disconnecting the ventilator is the same as post-extubation.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- With a newly extubated client, what oxygen delivery device do you typically use?

- What is the process of urgently re-intubating a client?

- How comfortable are you providing bag-mask ventilation to an apneic client?

- What is something from this course you can take back to your clinical practice?

- Does your workplace have a standardized approach to weaning ventilation? If not, how could the process be standardized?

Conclusion

In conclusion, the process of weaning a client off mechanical ventilation must be done carefully and systematically. It requires thorough assessment of the client’s readiness for weaning and risk factors for failure. Utilizing different ventilator modes can help smooth the transition from ventilator to independent breathing. Careful monitoring must be done during and after the weaning process to ensure the client is tolerating the transition. Hopefully this course has provided you with some insight into the many factors that play into a client’s ability to be liberated from the ventilator. With this knowledge you can confidently care for clients undergoing mechanical ventilation and assist them in their recovery towards breathing the free air again.

References + Disclaimer

- Akella, P., Voigt, L. P., & Chawla, S. (2022). To wean or not to wean: A practical patient focused guide to ventilator weaning. J Intensive Care Med, 37(11), 1417-1425. doi: 10.1177/08850666221095436.

- Elkins, M., & Dentice, R. (2015). Inspiratory muscle training facilitates weaning from mechanical ventilation among patients in the intensive care unit: A systematic review. J Physiother., 61(3), 125-34. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2015.05.016.

- Trudzinski, F. C., Neetz, B., Bornitz, F., Müller, M., Weis, A., Kronsteiner, D., Herth, F. J. F., Sturm, N., Gassmann, V., Frerk, T., Neurohr, C., Ghiani, A., Joves, B., Schneider, A., Szecsenyi, J., von Schumann, S., & Meis, J. (2022). Risk factors for prolonged mechanical ventilation and weaning failure: A systematic review. Respiration, 101(10), 959-969. doi: 10.1159/000525604.

- Roshdy, A. (2023). Respiratory monitoring during mechanical ventilation: The present and the future. J Intensive Care Med., 38(5), 407-417. doi: 10.1177/08850666231153371.

- Rose, L., & Messer, B. (2024). Prolonged mechanical ventilation, weaning, and the role of tracheostomy. Crit Care Clin., 40(2), 409-427. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2024.01.008.

- Kneyber, M. C. J., de Luca, D., Calderini, E., Jarreau, P. H., Javouhey, E., Lopez-Herce, J., Hammer, J., Macrae, D., Markhorst, D. G., Medina, A., Pons-Odena, M., Racca, F., Wolf, G., Biban, P., Brierley, J., & Rimensberger, P. C. (2017). Respiratory failure of the european society for paediatric and neonatal intensive care: Recommendations for mechanical ventilation of critically ill children from the Paediatric Mechanical Ventilation Consensus Conference (PEMVECC). Intensive Care Med., 43(12),1764-1780. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4920-z.

- Sangsari, R., Saeedi, M., Maddah, M., Mirnia, K., & Goldsmith, J. P. (2022). Weaning and extubation from neonatal mechanical ventilation: An evidenced-based review. BMC Pulm Med., 22(1), 421. doi: 10.1186/s12890-022-02223-4.

- Schreiber, A. F., Ceriana, P., Ambrosino, N., Malovini, A., & Nava, S. (2019). Physiotherapy and weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation. Respir Care, 64(1), 17-25. doi: 10.4187/respcare.06280.

- Mahmoodpoor, A., Fouladi, S., Ramouz, A., Shadvar, K., Ostadi, Z., & Soleimanpour, H. (2022). Diaphragm ultrasound to predict weaning outcome: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther., 54(2), 164-174. doi: 10.5114/ait.2022.117273.

- Girard, T. D., Alhazzani, W., Kress, J. P., Ouellette, D. R., Schmidt, G. A., Truwit, J. D., Burns, S. M., Epstein, S. K., Esteban, A., Fan, E., Ferrer, M., Fraser, G. L., Gong, M. N., Hough, C. L., Mehta, S., Nanchal, R., Patel, S., Pawlik, A. J., Schweickert, W. D., Sessler, C. N., Strøm, T., Wilson, K. C., & Morris, P.E.; ATS/CHEST Ad Hoc Committee on Liberation from Mechanical Ventilation in Adults. (2017). An Official American Thoracic Society/American College of Chest Physicians clinical practice guideline: Liberation from mechanical ventilation in critically ill adults: Rehabilitation protocols, ventilator liberation protocols, and cuff leak tests. Am J Respir Crit Care Med., 195(1), 120-133. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201610-2075ST.

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate