Course

VTE Prophylaxis

Course Highlights

- In this VTE Prophylaxis course, we will learn about pathophysiology of venous thromboembolism, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism.

- You’ll also learn high risk populations for venous thromboembolism.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of current best practices and medications for prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 2

Course By:

Jillian Hay-Roe

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

VTE is a common cause of morbidity and mortality. Hospital clients, in particular, often don’t receive appropriate prophylaxis. The goal of this course is to provide an overview of the causes, diagnosis and treatment for VTE. More importantly, methods to prevent VTE will be discussed, and nursing roles in facilitating this critical element of client care.

Glossary

Refreshing your nursing school days, here are definitions that will come up frequently throughout the following course [1][2][3]:

- Thrombus: (noun) The blood clot. A blood clot is made of several blood components including fibrin mesh, platelets and red blood cells. Multiple blood clots are referred to as thrombi.

- Thrombocyte: (noun) A platelet. These small blood cell particles have no nucleus. They function to clump together on the inside of a damaged blood vessel wall. Platelets and White blood cells together only make up approximately 1% of total blood volume.

- Thrombosis: (verb) the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel and blocks blood flow. [This slightly differs from coagulation, which is the process of clot formation to stop bleeding outside of the blood vessel. The process where bleeding outside the vessel is stopped is hemostasis (i.e. coagulation results in hemostasis)].

- Embolus: Any extraneous item (a clot, air bubble, fatty deposit, etc.) that is being carried through the bloodstream.

- Embolism: This describes when the inappropriate item (embolus) enters into the narrowed portion of the vessel causing a blockage of blood flow.

- Thromboembolism: This is specifically when the embolus is a blood clot and has caused a blockage in a blood vessel. There are both venous and arterial thromboembolisms. Venous thromboembolisms usually cause blockages in the lung vascular system. In the worst-case scenarios, arterial thromboembolisms result in myocardial infarctions (heart attacks) and cerebrovascular accidents (strokes). This course will focus on clots that affect the venous system.

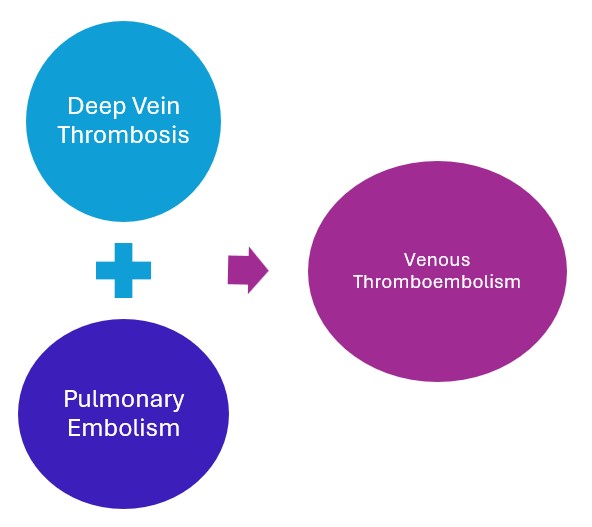

- Venous Thromboembolism: Simply put, this is any blood clot that forms in the venous system. Venous Thromboembolism is an umbrella term that includes both deep vein thromboembolisms and pulmonary embolisms.

- Deep Vein Thrombosis: (DVT) is a blood clot that forms within the deep veins, usually of the leg, but can occur in the arms and the mesenteric and cerebral veins.

- Pulmonary Embolism: (PE) occurs when a particle, most often a thrombus, has traveled through the blood stream and caused a blockage in the pulmonary artery or its branches. The embolism can consist of air, fat or tumor cells; however, this is rare. The vast majority of PEs are caused by a thrombus that has formed in a deep vein and has migrated into the pulmonary vessels.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you think of any pneumonic devices or techniques to help remember these different definitions?

- Why would it be beneficial to separate venous and arterial embolisms into different categories?

Pathophysiology

Physiology: Coagulation Cascade

It is amazing to think about all the roles that the vascular system serves. It is responsible for facilitating the delivery of oxygen, nutrients, hormones, thermoregulation, waste removal and protection against pathogens. At any point in time, nearly three-fourths of the circulating blood volume is contained in the venous system. Maintaining this system is so important, the vascular system also contains its own repair and self-protecting mechanisms. One of the protective mechanisms is designed to patch any leaks from vessel walls. [4][5][6]

Blood vessels are made of three layers, the innermost layer is referred to as the endothelium. In normal circumstances, it has anticoagulant and anti-platelet surfaces which allow the blood to flow freely through the vessel pathways. Blood contains both clotting and anti-clotting cell mediators simultaneously. They circulate and become activated in response to current needs present in the body.

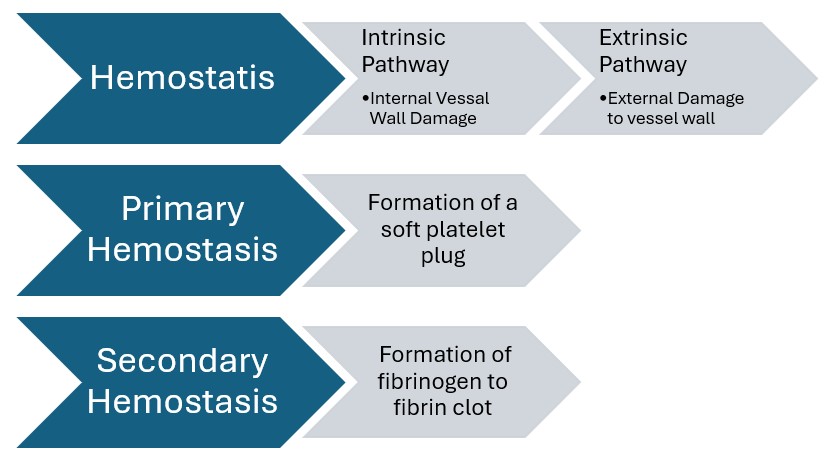

When there is injury to vessel wall endothelium, cells release a series of proteins and enzymes to reestablish hemostasis. The activation of the cells, proteins and enzymes in a stepwise fashion is called the coagulation cascade (AKA clotting cascade). When a person has an injury causing blood to leak out of the vascular system, hemostasis and the clotting cascade begin to work both inside and outside the vessel wall (AKA intrinsic and extrinsic pathways).

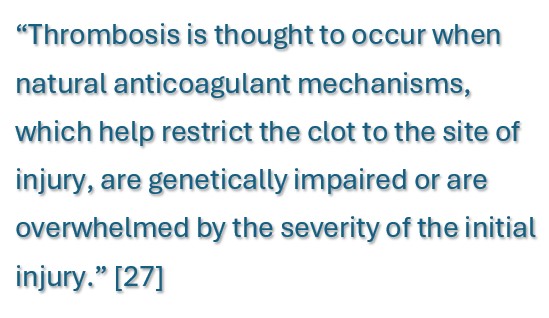

When injury is perceived inside the vessel wall only, the coagulation cascade will still activate to heal the site of injury in the vessel wall, resulting in formation of a thrombus. When the clotting extends past the area of endothelium injury, and begins to impede blood flow, it is considered a thrombus. A thrombus that impedes blood flow is problematic because it will decrease oxygen delivery to tissue and impede venous return to the heart and lungs.

Virchow’s Triad

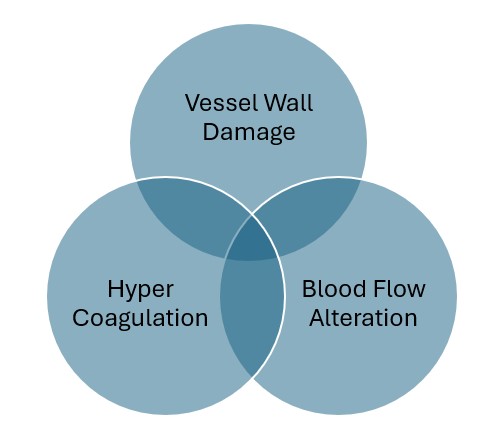

When delving into the pathophysiology of thrombosis, it always begins with Virchow’s Triad. Dr. Rudolf Virchow is credited with being the first to develop three factors that contributed to the formation of thrombi, in 1856. This was just one of his many contributions to medicine, and he is regarded as the “father of modern pathology.” [4][6] The following will explain the three factors that can lead to thrombosis: damage to the endothelial lining of a vessel wall, alteration in blood flow, and hypercoagulation.

Part 1: Damage to Vessel Walls

Endothelial vessel wall damage is caused by different factors. Direct causes include disruption of the vessel via catheter placement, trauma, or surgery. Indirect causes include, but are not limited to: inflammatory factors, life style (e.g. smoking), genetic, or a combination of lifestyle and genetic factors (e.g. hypertension and high cholesterol). [4]

When an insult to the wall occurs, flow disruption or “turbulence” occurs. Turbulent flow within a vessel occurs when the blood flow rate becomes too rapid, or blood flow passes over an affected surface. This causes friction within a vessel.” [4]

Part 2: Blood Flow Alteration

When there has been damage to the vessel wall, and friction occurs, there becomes disruption in blood flow. When flow is disrupted, numerous red blood cells, leucocytes, and platelets get strategically concentrated near the vessel wall for adhesion and activation. [7][8]

Venous stasis, decrease in blood flow throughout the vascular system is another factor in thrombosis. Muscle contraction is necessary to aid the flow of blood from certain parts of the body. Decreased movement, for example immobility after surgery, or long plane rides, contribute to venous stasis. This is the factor that contributes the most to formation of VTE. [7][8]

Part 3: Hypercoagulation

Hypercoagulation can result from enhanced or increased levels of clot forming components and activators present in the bloodstream. This hypercoagulability is due to a variety of factors that disrupt normal balance of anticoagulant and hemostatic components present in the blood. [4] The following are instances which can lead to an increase in the number of prothrombotic factors [4].

| Factors Associated with a Rise in Prothrombotic Factors | |

| Factor | Example Conditions |

| Acute inflammatory conditions |

|

| Increased thickness of blood and blood components |

|

| Genetic |

|

| Medications |

|

| Health Conditions |

|

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Why is it important for the body to be able to form clots inside vessel walls?

- A client exhibits ecchymosis, what damage has likely occurred to vessel walls?

- Why do you think that venous stasis is the biggest contributor to the development of VTE?

- How could you explain Virchow’s triad to a client in layman’s terms?

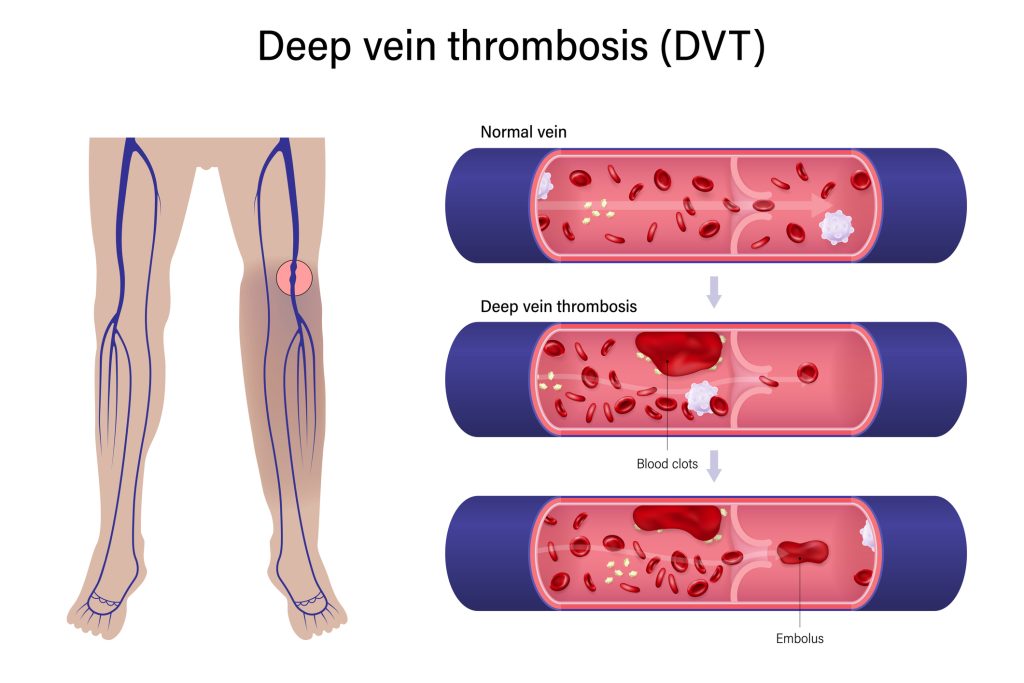

Deep Vein Thrombosis

The deep veins in the leg include the femoral, iliac and popliteal veins. Although less common, thrombosis can occur in the upper extremities, including the subclavian, axillary and brachial veins. They can even occur in more central veins, including superior vena cava, jugular vein, cerebral venous sinus and retinal veins. [2][6]

The life-threatening status of a thrombus that has the potential to break off and migrate is always the primary concern. However, a thrombus that remains attached to a vessel wall and impedes blood flow can also cause damage. [2][6]

Pulmonary Embolism

A pulmonary embolism (PE) occurs when a thrombus, or portion of the thrombus has broken off, and has become logged in the pulmonary artery or its branches. They are more likely to affect the lower lobes of the lung. Large emboli tend to obstruct the main pulmonary artery which causes cardiovascular problems. Smaller emboli block the peripheral arteries and can lead to infarction (tissue death). Infarction occurs about 10% of the time. [3]

When blood vessels are blocked by an embolus, there is a decrease in blood flow to the alveoli in the lungs. This prevents gas exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide from occurring. This reduction in adequate oxygen delivery (hypoxemia) to the body. This problem is exacerbated when serotonin mediators are released which causes vasospasm, which further decreases air flow in the unaffected lung areas. [3]

The blockage also causes an increase in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) and pulmonary artery pressure (PAP). This obstruction causes a backup of the cardiac circulatory flow and output, as well as interrupting cardiac rhythm. This results in systemic hypotension. PE can also lead to sudden cardiac arrest. Thirty percent of clients who do not receive treatment for PE will die.

Epidemiology

The precise number of people affected by either a DVT or PE is unknown, although as many as 900,000 people could be affected each year in the United States. An estimated 60,000-100,000 Americans die of VTE each year. This results in an average of one person in the US dying every 6 minutes. Acute venous and arterial thromboses are the most common cause of death in developed countries. VTE is the third leading cardiovascular diagnosis after a heart attack and stroke. [2][6][9][10][11]

VTE statistics are considered to be an underestimation. This is because clients with VTE do not always experience symptoms. Symptoms are often non-specific, which leads to a delayed diagnosis. Sudden death is the first symptom in about 25% of people who have a PE. Even in clients who do not develop PE, recurrent thrombosis and post-thrombotic syndrome are major causes of morbidity. [2][6][9][10][11]

Unfortunately, hospital treatment for one condition in the hospital setting can also lead to a VTE. “With 60% of VTE cases being hospital-acquired, VTE is the leading preventable cause of death in hospitalized clients.” [10] This also creates an economic impact. Medical costs in the United States are estimated at approximately $17,000 or more for clients who have a VTE event during or after a recent hospitalization. [2][6][9][10][11]

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some conditions that might cause a DVT to develop in the upper extremities or upper body?

- Why do you think that a DVT is most likely to lodge in the pulmonary system?

- Why would hypotension be a result of PE?

- Do you have personal experience with VTE or a risk of VTE that has occurred to you, an acquaintance or client?

- What is the impact of VTE in your clinical specialty(ies)?

Risk Factors

As usual, the chances of VTE development increase exponentially with age.

| Developmental Stage | Incidence |

| Childhood | 1 per 100,000 |

| Reproductive age | 1 per 10,000 |

| Late middle age | 1 per 1,000 |

| Geriatric | 1 per 100 |

| Overall Population | 1.6 per 1000 |

Transient Risk Factors Include:

- Surgery over 30 minutes with general anesthesia, especially hip or knee replacement

- Hospitalization for over 72 hours

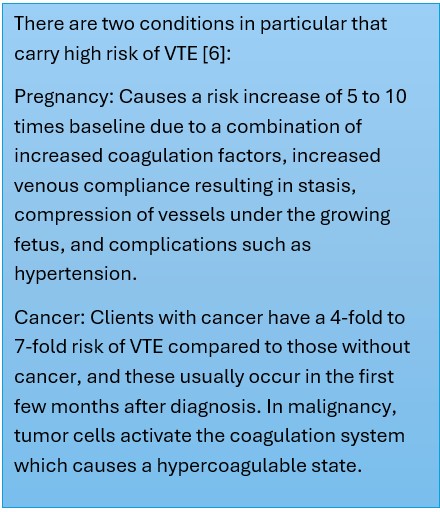

- Hormone replacement therapy and Oral contraceptives

- Pregnancy, C-sections and post-partum period

- Infection

- Lower extremity injury and limited mobility, especially fractures

- Central intravenous infusion lines

Persistent Risk Factors include:

- Inflammatory conditions such as lupus or inflammatory bowel disease

- Cancer and chemotherapy. Hematological malignancies, metastatic, pancreatic, lung, gastric, and brain cancer carry the highest risk for VTE.

- Chronic conditions (e.g. heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, hematological disorders)

- Previous blood clot or family history of clots

Modifiable Risk Factors

- Morbid obesity

- Smoking

A thrombus can still develop even if the client does not have any of these risk factors, which is called unprovoked VTE. Almost a third of PEs in clients are unprovoked. [3]

Case Study 1

A 35-year-old woman presents with 5 days of swelling and pain in her right lower extremity. She denies injury or trauma to the area. She states that the pain limits her ability to walk. Her past medical history is significant for obesity, birth control, sleep apnea, and hypertension. Vital signs are normal. Physical examination reveals right calf edema. The left leg examination is normal. What is most likely contributing to this client’s condition?

Answer: Birth control is most likely contributing to the client’s condition, but obesity and hypertension are also factors.

Signs and Symptoms

Obtaining the diagnosis of VTE only based on clinical signs and symptoms is notoriously inaccurate. The signs and symptoms of both DVT and PE are generally non-specific. They may be associated with other conditions or may be misdiagnosed. Up to 50% of clients with acute DVT may lack specific signs or symptoms. Providers need to obtain a client’s recent and familial medical history, medications to see if the client has any of the significant risk factors. They must also eliminate other possible diagnoses. [2][12]

If clients do develop signs, here are the most common for each VTE type:

| DVT | PE |

|

|

Case Study 2

A 75-year-old male is day five post-op following a left total knee replacement and is seen at the clinic for a normal follow up appointment. Vital signs are normal, and the client does not report any unusual symptoms, other than post-operative pain, which is controlled with ice and medication. The left knee leg is swollen but there is no redness, warmth or signs of infection. The nurse is unsure if the leg swelling is due to a DVT or is normal post-operative swelling. How should the nurse proceed?

Answer: Assess the client for other risk factors, consult with the surgeon to determine if further testing for DVT is warranted.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Consider the client population you routinely work with. What are common risk factors you identify in that population?

- What are some risk factors that you were already familiar with? Are there any risk factors that you were previously unaware of?

- What conditions could DVT or PE be otherwise mistaken for?

- If a client is exhibiting signs for both a DVT and PE, how would you proceed?

Diagnosis

DVT Diagnosis

There are some tools providers can use to help diagnose a DVT. [13] There are many scales available, each with pros and cons. Below is an example of one system, the Well’s criteria:

|

Well’s Criteria DVT Diagnosis: Clinical Findings |

|

|

1 point |

Paralysis, paresis or recent orthopedic casting of lower extremity |

|

1 point |

Recently bedridden (more than 3 days) or major surgery within past 4 weeks |

|

1 point |

Localized tenderness in deep vein system |

|

1 point |

Swelling of entire leg |

|

1 point |

Calf swelling 3 cm greater than the other leg (measured 10 cm below the tibial tuberosity) |

|

1 point |

Pitting edema greater in the symptomatic leg |

|

1 point |

Collateral non varicose superficial veins |

|

1 point |

Active cancer or cancer treated within 6 months |

|

-2 points |

Alternative diagnosis is more likely than DVT (Baker’s cyst, cellulitis, muscle damage, superficial venous thrombosis, post phlebitic syndrome, inguinal lymphadenopathy, external venous compression) |

|

DVT Risk Score Interpretation |

|

|

-2 to 0 points |

Low probability |

|

1-2 points |

Moderate Probability |

|

3-8 points |

High Probability |

For scores 2 or above, the following are the test diagnostic guidelines:

- D-dimer lab test (a normal level would rule out possibility of DVT)

- Coagulation profile (e.g. PT, PTT, aPTT, possibly INR, fibrinogen, platelets)

- Vein ultrasound (point-of-care or duplex ultrasound)

- CT Venograms

PE Diagnosis

PE is difficult to diagnose since the symptoms can be caused by several cardiothoracic causes. Essentially diagnostic tests must be completed and findings for other causes are then systematically ruled out. Like DVT diagnosis, there are tools available to help determine a diagnosis. [3][14] The following is just one example:

|

Well’s Criteria PE Diagnosis – Clinical Findings |

|

|

3 points |

Symptoms of DVT |

|

3 points |

No alternative diagnosis better explains the illness |

|

1.5 points |

Tachycardia with pulse > 100 |

|

1.5 points |

Immobilization (> = 3 days) or surgery in the previous 4 weeks |

|

1.5 points |

Prior history of DVT or PE |

|

1 point |

Presence of hemoptysis (bloody cough) |

|

1 point |

Presence of malignancy |

|

DVT Risk Score Interpretation |

|

|

<1 points |

Low probability |

|

2-6 points |

Moderate Probability |

|

>7 points |

High Probability |

When testing for a PE tests include the following:

|

Test |

Typical Results for PE |

|

Chest Xray |

Normal or non-specific abnormalities |

|

Arterial blood gas |

Hypoxemia with normal chest Xray |

|

D-Dimer |

Elevated (> 0.5mg/L) |

|

Troponin |

Elevated (>0.04 mg/mL) |

|

Brain Natriuretic Peptide (BNP); |

Elevated (>100 pg/mL) |

|

Electrocardiogram (ECG) |

Tachycardia (HR >100 bpm) or other nonspecific abnormalities |

|

Computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA) |

Visualization of a clot |

|

Ventilation/Perfusion Scan (V/Q Scan) |

Blockage of blood flow through the lungs (Used when CTPA is contraindicated) |

Case Study 3

A 66-year-old African American male presents complaining of chest pain and shortness of breath that started 3 hours ago. He recently traveled to Africa and just returned the day prior. He has a history of hypertension and takes amlodipine 5 mg daily. Vital signs are blood pressure 140/80 mm Hg, heart rate 110 bpm, and respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute. Laboratory results are unremarkable. Which of the following imaging studies is the most appropriate next step that can lead to the diagnosis?

Answer: Computed tomography pulmonary angiogram

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- If a clinician suspects a DVT, what factors might make diagnosis and treatment more or less urgent?

- What are some barriers to prompt diagnosis of PE?

- The Well’s criteria considers ‘no other diagnosis better explains the illness’ in determining the likelihood a client has a PE. What are other diagnoses that would be consistent with PE symptoms?

Treatment

In each client, the risks of anticoagulation need to be weighed against the benefits. Thereby treatment of VTE is complex and must be individualized to each client. Treatment may vary depending on whether it is a first episode or recurrent episode, the extent of the thrombosis clinical presentation, whether provoking risk factors are transient or persistent, and whether symptoms resolve. The treatment of VTE entails three stages: the initial, chronic, and extended stages. [6]

Initial Acute VTE Treatment

VTE treatment starts with the anticoagulant medications, primarily Heparin. Heparin works by activating antithrombin proteins circulating in the blood stream. Not all heparin is created equal. There are different types and different routes of administration which will have varying effects. [6][15][16][17][18]

- Unfractionated heparin is stronger and fast-acting. It is long and can wrap around both antithrombin and thrombin, holding them together, which neutralizes both proteins to prevent clotting. Lab tests need to be monitored frequently, and dosage adjusted accordingly. This can be administered IV or subcutaneous.

- Low-molecular-weight heparin has shorter molecules so that it only attaches to antithrombin. This results in longer-lasting effects and results in more stable changes in hemostasis. This can only be administered subcutaneously. Common drug names include: enoxaparin; dalteparin; tinzaparin

- Fondaparinux is a synthetic heparin which activates antithrombin over a longer period of time. It is weaker still than the other two kinds of heparin and is used more for prophylaxis rather than treatment. It is administered subcutaneously.

Management of acute DVT and PE in hospitalized clients typically includes anticoagulation with IV unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) with an eventual transition to oral anticoagulation medication. Heparin will not stop the growth of clots that have already formed, but it cannot decrease the size of clots that have already formed.

Preparing the correct dose using the correct concentration is critical. Heparin dosage is determined by severity and client weight. Most hospitals have adopted protocols to standardize dose adjustments. Clients with renal impairment also need special consideration. While clients are receiving heparin, they will need to have lab work collected frequently to monitor clotting speeds. There are also specific protocols for when labs should be obtained to titrate doses of IV heparin.

Heparin is considered by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) to be a high alert medication. High alert medications need special safeguards in place to reduce risk of errors that result in significant client harm. Safety measures include special labeling, storage, and independent double checks with two providers. Clients also require careful monitoring for signs of hemorrhage.

Some signs of hemorrhage that require attention include:

- Nosebleed or any unusual bleeding

- Easy bruising

- Blood in urine and/or stool (both frank and dark)

- Hematemesis (bloody vomit)

For clients who have severe bleeding as a result of heparin, there is an antidote medication available. Protamine can be administered in life-threatening situations. It must be administered slowly via IV over at least 10 minutes.

Another nursing consideration is the use of heparin (hep locks) to maintain patency of central IV lines. This is especially important in pediatrics or petite clients for whom these small doses can add up.

Thrombolysis

For clients with acute PE who are hemodynamically unstable, providers do not have time to wait for the effects of heparin to work. The clot causing backup of blood in the right ventricle can quickly cause death. Breaking up the clot quickly is the best way to restore cardiac and circulatory function. This can be achieved by catheter-directed thrombolysis, percutaneous aspiration thrombectomy, venous balloon dilatation, and pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis. [3][6]

|

Treatment Name |

Treatment details |

|

Alteplase (rt-PA) |

A thrombolytic medication that can be given via infusion, however it carries a high risk of bleeding complications. |

|

Catheter-directed treatment |

Insertion of a catheter into the pulmonary arteries, which is then used for ultrasound-assisted thrombolysis. Methods include suctioning, rotating, aspirating or fragmenting the embolus. In some situations, mechanical breakdown is combined with pharmacologic agents. |

|

Surgical embolectomy |

Indicated in a client with hemodynamically unstable PE in whom thrombolysis (systemic or catheter-directed) is contraindicated or in clients with failed thrombolysis. |

|

Vena cava filters |

These block the path of travel of emboli and prevent them from entering the pulmonary circulation. Filters are indicated in clients with an absolute contraindication to anticoagulants and in clients with recurrent persistent VTE despite anticoagulation. |

While anticoagulation efforts are underway, the PE client may need respiratory support via supplemental oxygen, and even mechanical ventilation. They may also need intravenous vasopressors or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in emergent situations.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What assessment techniques should the nurse use to evaluate signs of hemorrhage?

- What should be covered in client education regarding heparin?

- What are advantages and risks of thrombolysis treatments?

- What are clinical indicators that a client needs emergent thrombolysis?

Continued Treatment

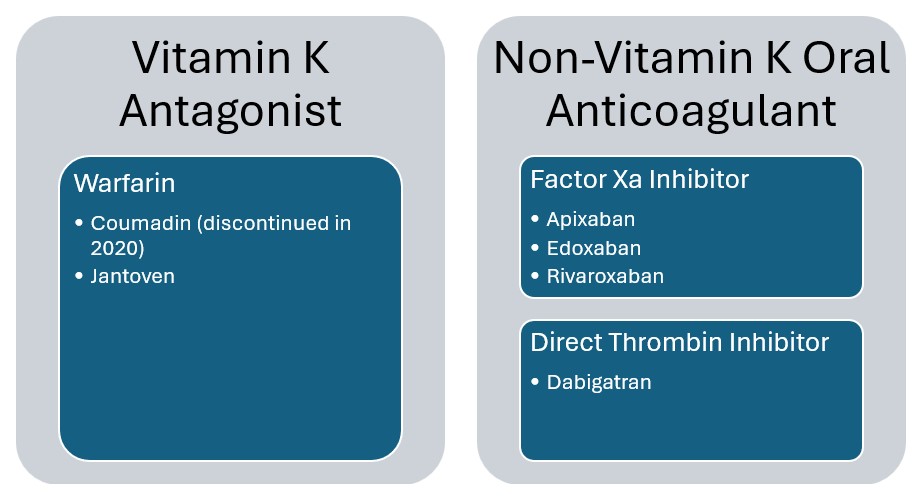

The treatment of both arterial and venous thrombosis differs. VTE management encompasses the use of various anticoagulant agents that target procoagulant factors, while arterial thrombosis (i.e. myocardial infarction and stroke clients) management is predominantly with antiplatelet agents (e.g. aspirin, clopidogrel). [6][19] The first oral anticoagulants were vitamin K antagonists (VKA). Several new medications have been developed roughly a decade ago and are referred to as non-vitamin-K-oral anticoagulants (NOACs) or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACS). Both drug types can be used for clients with DVT and PE who are clinically stable, and for extended prophylaxis. [6][19] Below are the two most common forms of each oral anticoagulant:

- VKA: Warfarin has been a standard of treatment for thromboembolism prophylaxis since the 1950s. This medication does come with some drawbacks. Warfarin works by inhibiting the synthesis of Vitamin K factors. Therefore, clients needed to be mindful to avoid eating or drinking foods that are high in Vitamin K. These include leafy green vegetables and some meats. Any anticoagulant medication carries the risk of bleeding, which can be exacerbated with alcohol and grapefruit juice. Clients require lab draws to test clotting with PT and INR ratios. Prescribers also have to watch for drug interactions. Warfarin takes 3 to 5 days for the best effect.

- NOAC: First marketed in 2012 for prophylactic stroke prevention in clients with atrial fibrillation, NOAC drugs gained additional FDA approval in 2014 for treatment of VTE. American Society of Hematology generally suggest the use of NOAC’s over VKA’s for most VTE conditions. They are continuing to demonstrate that they are more effective, easier to monitor, and have less bleeding. However, they are contraindicated in clients who have heart rhythm disorders and mechanical heart valves.

The following is a comparison of warfarin and NOAC [20]:

|

Comparing Factors |

Warfarin |

NOAC |

|

Onset of Action |

Slow |

Rapid |

|

Duration of Action |

Long |

Short |

|

Dosing |

Variable |

Fixed |

|

Food Interactions |

Yes |

No |

|

Drug Interactions |

Many |

Few |

|

Routine Lab Monitoring |

Yes |

No |

|

Reversal Agent available |

Yes |

No |

|

Cost |

Low |

High |

The following is a review of coagulation labs, and which are important to evaluate for specific medication treatments:

|

Medication |

Lab Test |

Normal Time |

Therapeutic Level |

|

Oral anticoagulants: Warfarin and NOACs |

Prothrombin Time (PT): The time it takes for blood to clot |

9-13 seconds |

1.5-2 times baseline (approximately 18-26 seconds) |

|

Heparin |

Partial Thromboplastin Time (PTT): Evaluates factor activation in the coagulation cascade and fibrin clot to form |

25-43 seconds |

60-100 seconds |

|

Unfractionated Heparin |

Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (aPTT): Same as PTT, but with an artificial activation factor added to the sample |

25-35 seconds |

1.5-2.5 times the control level, approximately (35- 70 seconds) |

|

Warfarin |

International Normalized Ratio (INR): a standardized measure of PT |

0.8-1.2 |

Target range of 2.0-3.0 seconds. |

|

Low Molecular weight heparin, (e.g. Enoxaparin) |

AntiFactor Xa Levels: Measured to assess therapeutic anticoagulant levels |

N/A |

Prophylaxis: 0.1-0.4 Therapeutic 0.5-2 units

|

Case Study 4

A 65-year-old woman presents with pain and swelling in the right leg for 1 week. A history of present illness reveals that she underwent a total hysterectomy, one month ago. She reported significant pain after the surgery and has not resumed daily walks. Her medical history includes obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia. On physical examination, her right leg is swollen and tender. There is a reddish-purple discoloration of the skin over the swelling. Doppler ultrasound shows a noncompressible venous segment with increased venous shadow. laboratory testing reveals her D-dimer is elevated. The provider has initiated unfractionated heparin therapy. What lab orders should the nurse anticipate?

Answer: Clotting studies including aPTT. Labs will most likely be collected at regular intervals based on a facility protocol.

Case Study 5

A 52-year-old male with a past medical history of pancreatic cancer, status-post Whipple procedure, presents to the clinic for follow up. He was diagnosed with right leg acute DVT two weeks ago. The clot was successfully treated, and the client is now taking maintenance warfarin daily. He reports no complaints and no signs of bleeding. His recent laboratory results show INR of 8.0. What is the next step in the management of this client?

Answer: Warfarin dose should be held. Since the client has no signs of bleeding, temporary cessation of warfarin is sufficient. There is no need for additional treatment. The client should have INR levels continually monitored before restarting a decreased dose of warfarin.

Extended Treatment

Ongoing treatment for clients who have had a VTE can also be convoluted and dependent upon several variables. For individuals who have had a VTE, they will need ongoing treatment for 3-6 months. Some high-risk clients may require prophylactic treatment indefinitely to prevent recurrence. For clients with Pharmacological VTE prophylaxis should also be continued until the client no longer has significantly reduced mobility (generally 5–7 days). For clients undergoing hip and knee replacement surgeries, the prophylaxis period is longer. [6][21]

Clients who are prescribed anticoagulants prophylactically for a temporary condition may only need the medication for a few days or weeks. The length of treatment of course will vary depending on initial causes and client risk factors. Factors providers must consider include the following: [6][12]

- Severity of VTE: Size of the clot and location where it was detected (e.g. small distal DVT or pulmonary artery)

- Event provoked or unprovoked: Did the VTE likely occur as a result of client circumstances, or was it random?

- VTE recurrence: Is this the first VTE the client experienced, or is this a recurrent episode?

- VTE risk factors: Does the client have a high-risk level for developing a VTE?

- Bleeding risk: Is the client at a high risk for bleeding?

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you think of some instances that would help determine the appropriate oral anticoagulant to prescribe a client?

- Why would anticoagulation medications be better for prevention of VTE than anti-platelet medications?

- What are some conditions that would require shorter term VTE treatment?

- What conditions would require long-term VTE treatment?

Long Term Effects

After the initial treatment and resolution of an acute VTE, clients may have ongoing sequelae. Even if the clients receive appropriate long-term VTE treatment and prophylaxis, other residual symptoms require other management. In addition to the physical symptoms, many clients report signs of psychological distress, including anxiety and sleep problems, which all together, reduce the client’s quality of life. [22][23]

Deep Vein Thrombosis Effects

Post-thrombotic syndrome is the most common long-term complication following a DVT. After DVT, post-thrombotic syndrome will develop in 20%-50% of clients. Severe cases occur in 5-10% of clients and can result in venous ulcers. Manifestations of post-thrombotic syndrome are similar to primary venous insufficiency, and include: swelling and sensations of pain, heaviness, pulling, or fatigue. The effected extremity may also present with redness, dusky cyanosis, varicose veins, or stasis hyperpigmentation. [22]

Pulmonary Embolism Effects

Post pulmonary syndrome may be experienced in up to half of clients who have survived a pulmonary embolism. Symptoms such as dyspnea, dizziness, chest pain, fatigue and discomfort during physical activity may continue and even become a chronic condition, although no residual thrombus is visible. Clients who are able to return to physical activity tend to have the best recovery. [23]

VTE Prophylaxis

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. VTE prophylaxis has been a part of client care plans for decades, particularly when clients are in higher risk situations. However, there is significant room for improvement. Some facts presented by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) include: [9][12][15]

- VTE is a leading cause of preventable hospital death in the U.S.

- As many as 70% of cases of healthcare associated VTE could be prevented, but fewer than half of hospitalized clients receive appropriate prevention measures.

- More than a third of blood clots diagnosed each year are related to a recent hospitalization and most of these do not occur until after discharge.

In response, The CDC has endorsed a “Stop the Clot, Spread the Word” public health education campaign developed with association of the National Blood Clot Alliance campaign in response. As it stands, about 33% of all hospital clients receive some form of anticoagulant medication. In the U.S., more than 5 million Medicare recipients received a prescription for an anticoagulant medication.

The prevention first begins with assessing risk for each client. Unfortunately, there is no consensus regarding the preferred VTE risk assessment tool. However, each facility can select their own. The Caprini VTE risk assessment was the first standard model first published in 1991. It was most recently adapted in 2013, and it can even be completed by the client.

There are now at least 15 different tools available, and different tools used in different settings (e.g. inpatient settings, ambulatory surgery centers, long-term care facilities). These tools help care providers to determine appropriate VTE prophylactic medications and mechanical, based on their risk level. They need to be updated regularly as client condition changes.

Inpatient will often have a standard order list that will be applied for each client. The following is an example of standard order sets: [12]

- No Prophylaxis, Ambulate

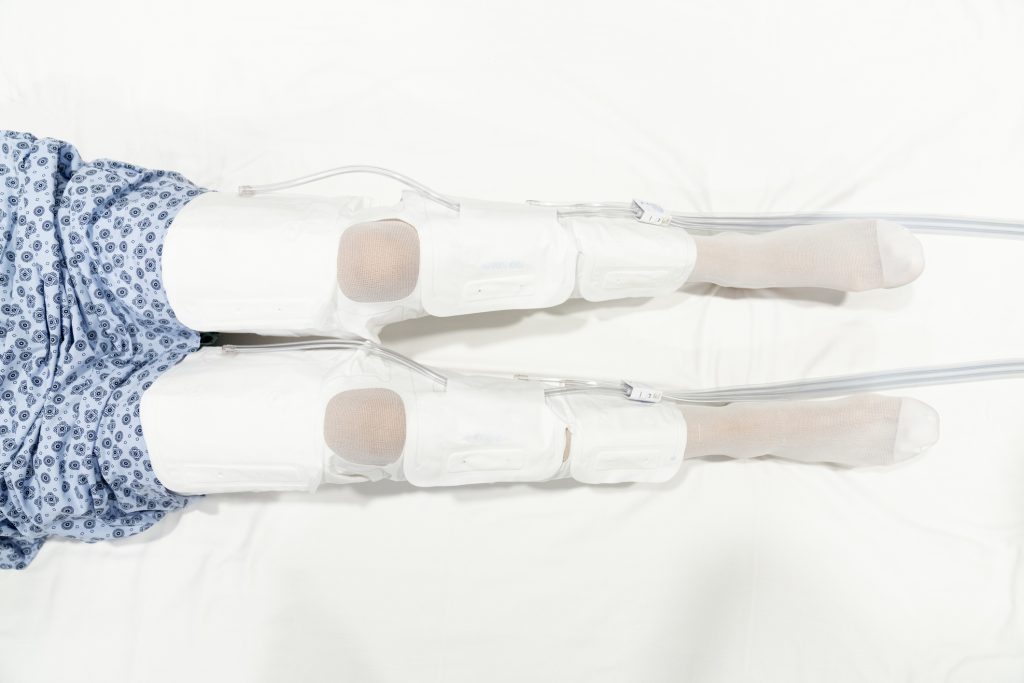

- Graduated Compression Stockings

- Sequential Compression Devices

- UFH 5,000 units SubQ q 12 hours

- UFH 5,000 units SubQ q 8 hours

- LMWH (Enoxaparin) 40 mg SubQ q day

- LMWH (Enoxaparin) 30 mg SubQ q 12 hours

- Other

Key: UFH = unfractionated heparin; SubQ = subcutaneous; LMWH = low-molecular-weight heparin.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What factors do you think contribute to the development of post-thrombotic and post-pulmonary syndrome?

- What could affect the severity of post-thrombotic or post-pulmonary syndrome?

- A client has difficulty regaining physical activity after a pulmonary embolism due to ongoing dyspnea upon exertion and overall fatigue. The nurse is aware that physical activity despite this will overall improve client outcomes. How can the nurse assist the client to achieve this goal?

- What are barriers to appropriate VTE prophylaxis?

- What would help improve rates of VTE prophylaxis interventions for clients under hospital inpatient care?

Mechanical Prophylaxis of VTE

Mechanical methods of VTE prophylaxis are very familiar to nurses. In addition to administering anticoagulant medications, the responsibility of delivering these interventions falls under the nursing role. There are three interventions: mobilization, sequential compression devices, and graduated compression stockings. [21][24][25]

These interventions on the surface appear to be simple. In busy inpatient care, they can be seen as lower priority and missed. However, they do serve an important purpose. Understanding the physiology and importance of these interventions can help motivate clinicians to maintain these a priority. The interventions may be the only ones available to clients for whom anticoagulant medication is contraindicated. These interventions do all require a physician’s order to initiate, because there are some conditions in which these devices are contraindicated.

Mobilization: Historically, clients with acute DVT were restricted to bedrest to prevent dislodging a clot and causing a PE. Immobility is now considered to be a risk factor for VTE as it results in venous stasis. New evidence demonstrates that early ambulation does not result in a higher incidence of PE or DVT progression. Ambulation for clients who are at higher risk due to surgery or hospitalization helps to prevent VTE. Ambulation also provides many other benefits to the client (e.g. prevention of skin breakdown, muscle wasting, joint stiffness, pulmonary infection, gastrointestinal delays). [24]

A hindrance to this intervention is clients who are immobilized or who require bedrest for other diagnoses (e.g. women with high-risk pregnancies). In this instance, clients can still benefit from performing range of motion exercises, such as leg lifts, flexing/extending feet and toes, ankle rolls. For clients who are unable to move independently, other care providers, such as physical therapists, can assist with passive range of motion.

In between exercise sessions, the following measures can also be used:

Sequential Compression Devices (SCDs): These are also referred to as Intermittent Pneumatic Compression Devices (IPC). These are available in knee-length and thigh-high. Nurses must make sure to apply the correct size sleeve. Many sleeves come with measuring guides already on them. Nurses should conduct a baseline skin assessment and neurovascular assessment. Assessment should include skin abnormalities, presence of pain, paresthesia, paralysis, edema, distal pulses. The devices should be removed for reassessment every 8 hours. This may coincide with other client care measures such as ambulation or bathing. [25]

Some clients may be prescribed SCDs as medical equipment to use at home. Some are adapted with a battery so they do not need to be attached to tubing and a pump, which will help client compliance. Some clients may enjoy the massage like feeling, while others complain of being hot or itching and be non-compliant with wearing them. [25]

Graduated Compression Stockings: Also referred to as antiembolism stockings or T.E.D hose (a name brand). These exert graded pressure and a decreasing gradient from ankle to high. They are also available at different levels of compression pressure. This results in an increase in blood flow velocity, which promotes venous return. The use of compression stockings is contraindicated in clients with peripheral arterial disease, neuropathy, impaired skin integrity, congestive heart failure. [21]

They are available in both knee-length and thigh-high. There is currently no evidence to support one length over the other. They also come in different sizes which require measuring leg circumference and length to ensure the correct size. Stockings should be kept on at all times but should be removed for bathing and to assess the skin and extremity. [21]

Stockings can be difficult to apply and cause discomfort for some clients, which may decrease client compliance. Knee-length stockings tend to be more tolerable and are more likely to be worn correctly. Stockings that are the incorrect size can roll down can cause an unsafe tourniquet effect. Stockings that are too large are ineffective. Wrinkled stockings can cause skin breakdown. They can also lose elasticity and compression effect over time, and they may need to be replaced periodically, as indicated on the packaging. [21]

Cautions to Prophylaxis

Treatment and prophylaxis of VTE undisputably saves lives. However, all medications come with side effects. Excessive bleeding is the ever-present danger when treating clients. Clients who require surgery may need to have a temporary pause in anticoagulation medication to prevent excessive bleeding. The balance between anticoagulation and hemorrhage is very delicate, and providers must be vigilant to make sure they maintain a safe benefit to risk ratio. Major bleeding can be fatal or cause bleeding into a critical area such as the intracranial or pericardial area. It is quantified as a fall in hemoglobin level by 2 g/dl or more; or requiring a transfusion of 2 or more units of blood. [26]

There are also multiple assessment tools to help determine a client’s risk for bleeding. This may also help guide the provider with appropriate dosing to maintain the safety ratio:

| VTE-BLEED Risk Score | |

| 2 points | Active Cancer |

| 1 point | Male client with uncontrolled arterial hypertension |

| 1.5 point | Anemia |

| 1.5 point | Renal dysfunction |

| 1.5 point | History of bleeding |

| 1.5 point | Age > 60 years |

| DVT Risk Score Interpretation | |

| 0-1.5 points | Low Risk |

| >2 | Elevated Risk |

Client Education

As always, client education is important, and the responsibility largely falls on nurses. This is a critical especially for clients being discharged from the hospital, since a large percentage of VTEs develop during that time. With clients being discharged as soon as medically possible, many clients will continue to have lots of sedentary time as they convalesce. As healthcare has evolved, so has the education load for clients. With this in mind, nurses need to also consider what are the most important components for the client to remember so they don’t overload them with information. These are aspects nurses need to consider when providing client education:

- What is the client’s risk level: You can utilize elements from your institution’s VTE risk assessment scoring tool to determine if your client is high, low, or medium risk. Clients should be aware of where they stand.

- Clients who have experienced a VTE will require education about the likelihood of recurrent thrombosis. One-third of people with a VTE will have a recurrence within 10 years.

- Signs and symptoms of DVT and PE

- What to do if they have symptoms: When they should call their doctor vs when they need to call an ambulance.

- Long term complications or effects.

- Anticoagulant medications:

- When they should be administered and duration of therapy (i.e. days or months)

- How (injection or oral)

- For SubQ injections, the client should be taught how to administer the injection in the abdomen, rotating sites, and avoid rubbing the site. Bruising of the injection site is not uncommon.

- Any follow up lab testing requirements.

- Any dietary restrictions.

- Side Effects and precautions (i.e. bleeding signs and symptoms)

- Non-pharmacologic prophylaxis:

- Ambulation, exercises at rest, or passive range of motion exercises to be completed by a home care provider.

- Compression stockings, or SCD’s if prescribed. Include teaching how to properly apply and maintain.

- Lifestyle modifications to reduce risk factors like smoking cessation and healthy weight maintenance.

Case Study 6

A 20-year-old is recently diagnosed with Hodgkins’s lymphoma. The nurse at the outpatient chemotherapy infusion clinic begins teaching the client and their parent about VTE prophylaxis. The parent asks the nurse “I thought only older people traveling on airplanes got blood clots, why are you telling us about this?” How can the nurse respond?

Answer: The nurse can provide education to the family that while it is true, older individuals and those who have limited mobility during long travel periods have increased risk of VTE, individuals who have a diagnosis and are receiving treatment for cancer are at high risk for development of VTE.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some specific barriers that prevent clinician and client compliance with VTE prophylaxis therapies?

- What other healthcare team members facilitate the implementation of VTE prophylaxis interventions?

- In order of importance, how should the nurse cover each topic of VTE education?

- How can the nurse help verify the client has understood VTE education?

- Can you think of any other topics or elements that the nurse should incorporate into client education?

- Evaluate your VTE prophylaxis measures in your clinical area. Do you think there is room for improvement?

- What changes do you think you could implement?

Conclusion

Statistics show that VTE is undeniably common in the U.S., and that we are not doing as much as we can to prevent this problem. Hopefully, this course has brought awareness of the pervasiveness of this condition, and more importantly, what needs to be done to reduce it. By understanding the pathophysiology of how clots form, it allows clinicians to understand the factors that increase clients’ risk. The goal is that this knowledge will place a higher priority on the prophylaxis of VTE, not only by instituting prophylaxis interventions, but by enlisting client involvement with education.

References + Disclaimer

- A. LaPelusa and H. D. Dave, “Physiology, Hemostasis,” StatPearls [Internet], 1 May 2023.

- S. M. Waheed, P. Kudaravalli and D. T. Hotwagner, “Deep Vein Thrombosis,” StatPearls [Internet], 19 January 2023.

- V. Vyas, A. Sankari and A. Goya, “Acute Pulmonary Embolism,” StatPearls [Internet], 28 February 2024.

- A. Kushner, W. P. West, M. Z. Khan Suheb and L. S. Pillarisetty, “Virchow Triad,” StatPerals [Internet], 7 June 2024.

- W. Barmore, T. Bajwa and B. Burns, “Biochemistry, Clotting Factors,” StatPearls [Internet], 24 February 2023.

- D. Ashorobi, M. A. Ameer and R. Fernandez, “Thrombosis,” StatPearls [Internet], 12 February 2024.

- W. D. Tucker, Y. Arora and K. Mahajan, “Anatomy, Blood Vessels,” StatPearls [Internet], 8 August 2023.

- M. Badireddy and V. R. Mudipalli, “Deep Venous Thrombosis Prophylaxis,” StatPearls [Internet], 7 May 2023.

- Center for Disease Control, “Data and Statistics on Venous Thromboembolism,” [Online]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/blood-clots/data-research/facts-stats/index.html.

- S. Vaqar and M. Graber, “Thromboembolic Event,” StatPearls [Internet], 22 May 2023.

- A. J. Darzi, A. B. Repp, F. A. Spencer, R. Z. Morsi, R. Charide, I. Etxeandia-Ikobalzeta, K. A. Bauer, A. E. Burnett, M. Cushman, F. Dentali, S. R. Kahn, S. M. Rezende, N. A. Zakai, A. Agarwal, S. G. Karam, T. Lotfi, W. Wiercioch, R. Waziry, A. Iorio, E. A. Akl and H. J. Schunemann, “Risk-assessment models for VTE and bleeding in hospitalized medical patients: an overview of systematic reviews,” Blood Advances, vol. 4, no. 19, pp. 4929-4944, 13 October 2020.

- G. Maynard MD, Preventing hospital-associated venous thromboembolism: a guide for effective quality improvement, 2nd ed., Rovkville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2015.

- Merck & Co., Inc, “Professional / Clinical Calculators / DVT Probability: Wells Score System,” merk Cmannual Professional Version, [Online]. Available: https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/multimedia/clinical-calculator/dvt-probability-wells-score-system.

- Merck & Co., Inc., “PE Probability: Wells Score System,” Merck Mannuals, [Online]. Available: https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pages-with-widgets/clinical-calculators?mode=list.

- Cleveland Clinic, “Anticoagulants,” 10 January 2022. [Online]. Available: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/22288-anticoagulants#when-to-call-the-doctor.

- AHFS Patient Medication Information, “Heparin Injection,” American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 15 September 2017. [Online]. Available: https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a682826.html.

- L. B. Warnock and D. Huang, “Heparin,” StatPearls [Internet], 10 July 2023.

- Institute of Safe Medication Practices, “ISMP List of High-Alert Medications in Acue Care Settings,” ISMP, [Online]. Available: https://www.ismp.org/system/files/resources/2024-01/ISMP_HighAlert_AcuteCare_List_010924_MS5760.pdf.

- R. H. Zaidi and P. Rout, “Interpretation of Blood Clotting Studies and Values (PT, PTT, aPTT, INR, Anti-Factor Xa, D-Dimer),” StatPearls [Internet], 8 June 2024.

- R. K. Wadhera MD, C. E. Russell MD and G. Piazza MD, “Warfarin Versus Novel Oral Anticoagulants: How to Choose?,” Circulation, vol. 130, no. 22, 25 November 2014.

- R. Wade, E. sideris, F. Paton, S. Rice, S. Palmer, D. Fox, N. Woolacott and E. Spackman, “Graduated compression stockings for the prevention of deep-vein thrombosis in postoperative surgical patients: a systematic review and economic model with a value of information analysis,” Health Technology Assessment, vol. 19, no. 98, November 2015.

- S. R. Kahn, “The post-thrombotic syndrome,” Hematology. American Society of Hematology, Education Program, vol. 2016, no. 1, pp. 413-418, 2 December 2016.

- A. A. Hojen, P. B. Nielsen, T. F. Overvad, I. E. Albertsen, F. A. Klok, N. Rolving, M. Sogaard and A. G. Ording, “Long-Term Management of Pulmonary Embolism: A Review of Consequences, Treatment, and Rehabilitation,” Journal Clinical Medicine, vol. 11, no. 19, p. 5970, 10 October 2022.

- V. Chatsis and S. Visintini, “Early Mobilization for Patients with Venous Thromboembolism: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness and Guidelines,” Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, 17 January 2018.

- C. Moore and J. Nichols-Willey, “Enhancing patient outcomes with sequential compression device therapy,” 11 August 2013. [Online]. Available: https://www.myamericannurse.com/enhancing-patient-outcomes-with-sequential-compression-device-therapy/.

- M. C. Badescu, M. Ciocoiu, O. V. Badulescu, M.-C. Vladeanu, I. B. Bojan, C. E. Vlad and C. Rezus, “Prediction of bleeding events using the VTE-BLEED risk score in patients with venous thromboembolism receiving anticoagulant therapy (Review),” Experimental and therapeutic medicine, vol. 22, no. 5, p. 1344, 22 September 2021.

- R. W. Colman, “Are hemostasis and thrombosis two sides of the same coin?,” Journal of Experimental Medicine, vol. 203, no. 3, pp. 493-495, 20 March 2006.

- Cleveland Clinic, “Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia,” 12 August 2022. [Online]. Available: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/24014-heparin-induced-thrombocytopenia.

- H. J. Schunemann, M. Cushman, A. E. Burnett, S. R. Kahn, J. Beyer-Westendorf, F. A. Spencer, S. M. Rezende, N. A. Zakai, K. A. Bauer, F. Dentali, J. Lansing, S. Balduzzi, A. Darzi, G. P. Morgano, I. Neumann, R. Nieuwlaat, J. J. Yepes-Nuneq, Y. Zhang and W. Wiercioch, “American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients,” Blood Advances, vol. 2, no. 22, pp. 3198-3225, 27 November 2018.

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

To receive your certificate