Course

Watchman Device

Course Highlights

- In this Watchman Device course, we will learn about an indication for the Watchman device.

- You’ll also learn the procedure for inserting the Watchman device.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of the nurse’s role in educating and supporting the client with a Watchman device.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 1

Course By:

Elaine Enright, ADN, BSN, RN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

This course has been developed to assist nurses in learning and understanding the Watchman implantable device, which prevents blood clots from entering the vascular system. We will discuss atrial fibrillation as the leading cause of blood clots and what drugs or treatments have been used today and in the past. We will identify the types of clients who may qualify for the Watchman device and learn how and where it is implanted. We will also discover what clients are most likely to need the device and what the role of nursing is in preparing and educating the client pre-op and caring for them post-op. This course also includes the pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation and how the Watchman works in this arrhythmia.

Definition

The Watchman is a newer device implanted in an area of the heart called the Left atrial appendage (LAA) to protect clients from developing and releasing thrombi. It is implanted in clients by occluding the LAA for those with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (AF). We know AF is an arrythmia that can cause the formation of clots, and the LAA is where most of them form (2). We will review the anatomy and physiology of AF and this atrial appendage, which plays a fundamental part in clot formation.

This course will discuss current treatments and explore the Watchman device and others that might be available.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some issues with clients taking warfarin?

- Can you locate the L atrial appendage in the heart?

- What is the mechanism causing clots to form in the L atrium?

- Have you seen or worked with the Watchman?

Epidemiology of Atrial Fibrillation

There are more than 37 million cases of atrial fibrillation (AF) worldwide (2). In the U.S., there are approximately 2.7 million clients with AF. Scientists have found that clients with an immediate family history have a 40% chance of developing this arrythmia (10). Familial cases of AF were first identified before 2000. This caused scientists to begin genetic studies of the problem. In Scotland, a study revealed that AF incidence was higher in men than women (10). They also identified that AF increases with age. Per 1000 persons in a study, the percentage of clients with AF ages 45-54 was 0.5 %, 55-64 was 1.1%, 65-74 was 3.2 %, and in the oldest population, the incidence rate was 4.98%-9.33% respective to age (10).

In Hispanic and Asian clients living in the U.S., the ratio of those with AF was 6.1 Hispanics per 1000 people and 3.9/1000 for Asians. Ratio for White clients in the U.S. was 11.2/1000. As we know, ischemic stroke is a primary concern in those clients with AF and is less common in those of African descent compared to those of European descent. However, more studies have shown that ethnicity, race, and “genetic ancestry variants” are more susceptible to acquiring AF (10).

Females have a lower risk of developing AF, but their lifetime risk is similar to men’s because men have a shorter lifespan (10). AF is predicted to affect 6-12 million people by 2050. In Europe, that number is 17.9 million by 2060 (1).

AF causes an extremely high burden on economics, mortality, and morbidity (2). It has tripled in the last 50 years, primarily because of an aging population (3). AF also raises the risk for heart failure and stroke by 5-fold, dementia by 2-fold, and death by 1.5-1.9 (3).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you research the burden of the cost of AF in the U.S.?

- Where can you find literature proposing family history before 2000?

- How might AF cause dementia?

- Is there a reason Americans have a higher rate of AF?

- Why are men at higher risk of developing AF?

Etiology and Risk Factors for Atrial Fibrillation

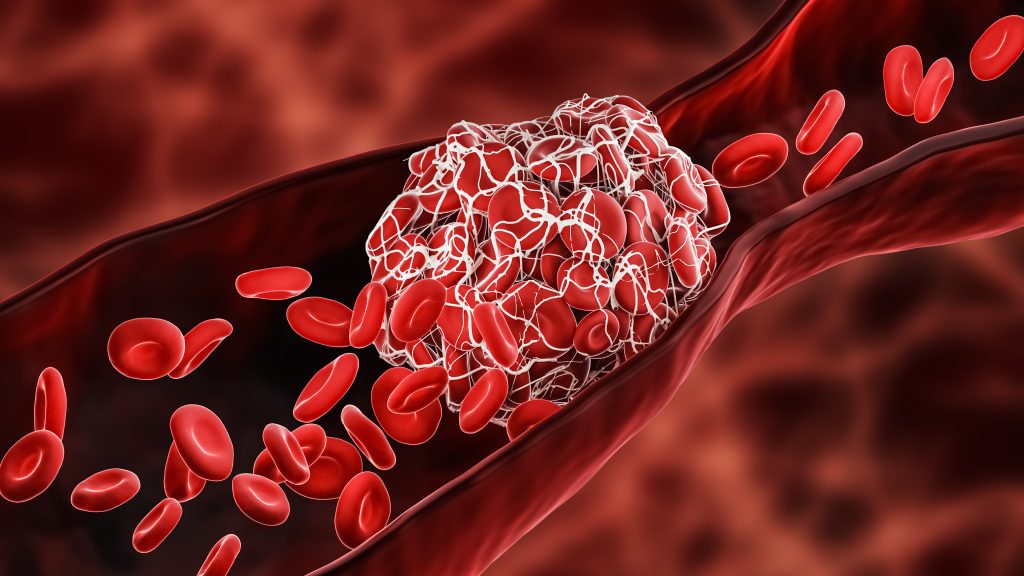

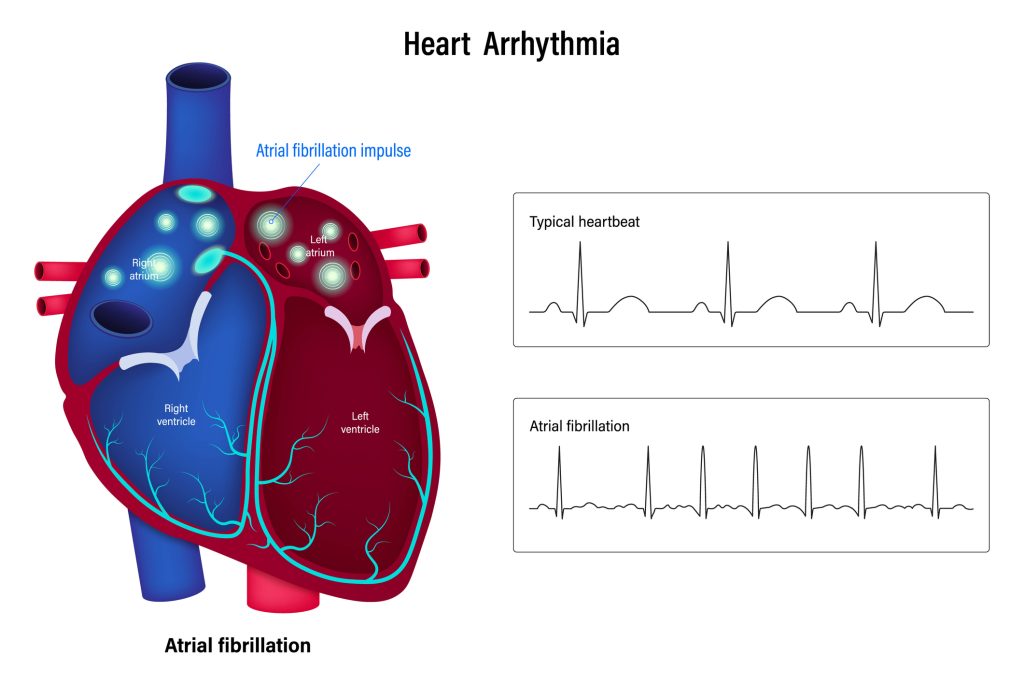

We know that AF is a cause of several issues, forming blood clots, ischemic stroke, and myocardial infarction being the most concerning. But do we know what causes AF? The prevailing belief is that “high-frequency excitation” or an abnormal electrical impulse in the left atrium causes fibrillation, hence a tachyarrhythmia (10). These issues change the atrial and ventricular structures. When looking at an ECG, you will find P waves replaced by F waves or fibrillation waves (13) [See Image 1].

[Figure 1. Atrial Fibrillation versus Normal Sinus Rhythm

This disruption of electrical activity also causes turbulence in the L atria, where blood pools in the LAA, where 90% of clots form (11). The clots may dislodge, become embolisms, and cause a stroke. Heart restructuring can also bring on AF. The causes for restructuring are not well understood; however, potential causes are (11):

- Atrial ischemia

- Inflammation

- Alcohol and illicit drugs

- Hemodynamic stress

- Neurological and endocrine disorders

- Advanced age and

- Genetic factors

Diagnosing and stratifying clients with AF helps determine the stroke risk and the best way to treat it. Some clients may be asymptomatic, while others have palpitations, weakness, chest pain, edema in the lower extremities, dizziness, and dyspnea on exertion. Risk factors that may elicit AF are long-standing hypertension, heart disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and valvular disease. Modifiable risk factors include alcohol intake, smoking, illicit drugs, obesity, and high cholesterol (11). Fibrillation decreases contractility, which stagnates blood in the LAA, allowing clot formation (6). Next, let us look closely at the risk factors for atrial fibrillation (AF).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you find an EKG that shows AF?

- Where in the body can other clots occur?

- How would you care for and educate a client with AF as a nurse?

- What components make older age a risk factor for AF?

Hypertension

According to the Framingham Study, there is a strong link between long-term hypertension and AF. L atrial pressure and stiffening from prolonged hypertension can cause remodeling of the left atria and ventricle tissues, which become hypertrophied, affecting diastolic function (12). This remodeling increases the chance of developing AF. The electric conduction in the atria also functions poorly since the atrium becomes stretched, allowing the blood to stagnate in the LAA, increasing the chance of developing AF (12). This also causes the L ventricle to enlarge and become hypertrophied.

Diabetes

Diabetics have a greater risk (34%) of developing AF as glucose fluctuations are arrhythmogenic. Oxidative stress and inflammation show high C-reactive protein and contribute to myocardial fibrosis or stiffening. Furthermore, more diabetics show an added expression of proteins at the cellular level and slower conduction due to changes in the sodium/calcium channels, also leading to myocardial fibrosis (12).

Heart Failure

Clients who have congestive heart failure are at a high risk of developing AF because of connective tissue that is compromised. This causes increased hypertrophy of the L atrium (13). It is worse in those with preserved ejection fraction (EF) than those with abnormal or low EF. Heart failure is the most common cause of mortality in clients who are anticoagulated and have low EF (13).

Age

Older clients are at higher risk for AF because of advancing age and comorbidities (10). The male gender is the primary non-modifiable risk factor, as is those who are Caucasian (12).

Obesity and Obstructive Sleep Apnea

The worsening obesity in the Western world has contributed to sleep apnea. The epicardium also has increased fat thickness, which can contribute to anomalies in the heart’s chambers (12). Studies have shown that clients with lower high-density lipids (HDL) and high triglycerides showed a higher incidence of AF. Alternatively, the same studies have not demonstrated decreased AF in clients with low-density lipids (LDL) (12).

Smoking

Smoking causes nicotine-induced oxidative stress and inflammation, which result in fibrosis of the atrium. Current smokers are at higher risk (32%) than those who are former smokers. Chemicals inhaled with smoking cause changes in the heart and blood vessels, which can also contribute to AF.

Alcohol is a risk for those who drink more than 35 drinks per week. It can cause hypertension, cardiomyopathy, irregular heartbeat, and stroke. At the same time, a moderate intake of alcohol can raise HDL (15). The recommendation is one drink per woman and two for males daily.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What does too much alcohol do to cause AF?

- Do you know someone with AF, and what are the underlying causes?

- Why would high lipids cause a client to develop AF?

- How can you assist clients with these risks to mitigate developing AF?

Types of Atrial Fibrillation

To treat the client with AF, the provider must diagnose its underlying cause. A study has defined a classification system to assist providers. The European Society of Cardiology has described the types of AF (12):

- AF: caused by secondary structural l heart disease, including long-term HTN with left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and other structural abnormalities

- Focal AF: Paradoxically, a client may have frequent short runs of AF, which affects the heart structures and puts them at risk of chronic AF.

- Polygenic AF: Early onset of AF due to shared genetic elements.

- Post-Operative AF: It usually occurs after significant surgery, mainly cardiac, in clients with no prior history of AF.

- Valvular AF: Clients with mitral stenosis or prosthetic heart valves

- AF in Athletes: This type of paroxysmal AF refers to the intensity and duration of training

- Monogenic AF: This is present in those who have inherited cardiomyopathy and channelopathies

Historical Implications of Atrial Fibrillation

Let us examine the history of AF. In 2000 BC, Xuanyuan Hyuangdi, the Yellow Emperor of China, wrote in his medical book, “When the pulse is irregular and tremulous, and the beats occur at intervals, then the impulse of life fades.” – The Yellow Emperor” (19). Do you think he was writing about AF but did not name it?

In 1628, an English physician saw firsthand how the L atrium fibrillates.

In 1775, another physician introduced foxglove (digoxin, digitalis) in a dose that allowed the heart to beat regularly again. However, digoxin has many side effects and needs to be tested for therapeutic levels.

The ECG was developed in the early 1800s, and two scientists determined that the oscillating waves on the ECG of the L atria were AF. In 1998, scientists demonstrated that AF could be ended by catheter-based isolation of some ectopic pulmonary vein triggers. (19)

We have certainly made great strides in figuring out the pathophysiology of AF and developing targeted therapies. We must also carefully find the correct medication/procedure for each client. Could differing treatments hold the answers to mitigating AF in each client?

Around 1900, two scientists conducted the first experiments to explain how AF works. Their thought was that AFib resulted from increased activity of an ectopic focus. At the same time, scientists were developing the electrocardiogram (ECG). (19)

Another English physician was conducting electrophysiological experiments on clients with AF. He was the first to determine that the fine diastolic oscillations on ECG “squiggly waveforms” represented the fibrillatory activity of the atrium. He also hypothesized that these reentrant waves, or circus movements as they were named, were the most plausible explanation for AF continuing. For the next 30 or so years, re-entry was believed to be the prevailing mechanism for AFib. (20)

Today’s question is how to offer each client different mechanisms to mitigate this problem and prevent morbidity and mortality. We will focus on that in the next section.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Why do you think surgery causes AF in clients with no history of AF?

- Can you find more information about AF discovered in the past?

- What causes an athlete to develop AF?

- Can you look at an ECG and determine if it shows AF?

- How fast does the heart beat in AF?

Treatments

The best way to reduce the incidence of AF is to change modifiable risks (16). All clients who are at risk for AF should quit smoking, lose weight, exercise, and drink less alcohol.

For all clients, there are three classes of drugs used to control AF: those that control the heart’s rhythm, rate control, and stroke prevention (16). The goal of these medications is to maintain sinus rhythm (16). Presently used drugs are IV or oral Flecainide (antiarrhythmic class C), IV or oral Propafenone (antiarrhythmic class IC), Oral Sotalol (antiarrhythmic and beta-blocker), IV or oral Amiodarone (antiarrhythmic Class C) IV, Ibutilide, (antiarrhythmic III), and oral Dronedarone (antiarrhythmic class III) (16).

Anticoagulants are also used, depending on the risk stratification of a client with AF (11). The risk-stratifying system used is called the CHADs-2-Vasc scoring system. This system measures “Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age 75 years or older, Diabetes, and Stroke” (11). If a client scores 0, no anticoagulants are needed. If the score is 1, anticoagulant or antiplatelet medication can be considered. If the score is 2 or above, it is essential to prescribe anticoagulants (11).

Cardiac labs, such as brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), should be done to ascertain if there is an underlying cardiac problem. Sometimes, the provider will request a cardiac catheterization if the client’s history warrants it (11). Other labs should also be drawn to assess renal and liver functions for some anticoagulants. It is also essential to do d-dimers or spiral CT scans to assess for pulmonary embolism.

Cardioversion is widely used as part of a rhythm control strategy in clients who have recent or new onset of AF (17). Although cardioversion complications are rare overall, assessing the client’s thromboembolism risk is paramount before the cardioversion (17). Nurses will educate and support the client regarding anticoagulation before the procedure and the necessity for compliance with older and novel oral anticoagulants (NOAC) treatment). After the procedure, it is essential to have regular check-ups to:

- Identify AF recurrences

- Ensure the rhythm control therapy is working well

- Check symptoms

- Improve treatment of underlying heart conditions

Cardioversion may be done by direct shock, electrical shock, and pharmaceuticals. These procedures are safe and readily available (17). Electrical cardioversion has a high rate of terminating AF. Pharmaceutical treatment is used in new or recent onset of AF and is effective in 50-70% of clients. (17)

In clients with symptomatic AF and in whom antiarrhythmic drugs have not worked, catheter ablation helps improve symptoms. In younger clients with no or few comorbidities who have symptomatic paroxysmal AF, catheter ablation is a good alternative that can improve symptoms and lessen progression to AF. Catheter ablation is also recommended in appropriate clients who have AF, heart failure, and reduced ejection fraction (5).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How did newer anticoagulants like apixaban and rivaroxaban develop?

- Can you find more information on the CHADs-2 vascular system?

- What are the side effects of the newer anticoagulants such as apixaban and rivaroxaban?

- What is the voltage used for cardioversion?

- When was the catheter ablation first trialed, and what were the outcomes?

Left Atrial Appendage

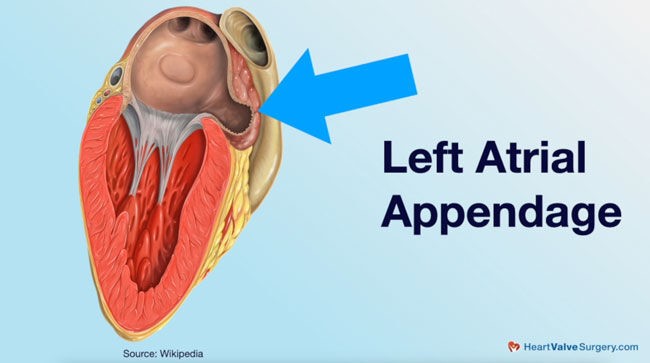

We have discussed AF and the left atrial appendage extensively, but what is the LAA, and where is it? See Figure 1.

The Left atrial appendage (LAA) is a finger-like protrusion or a pocket in the L atrium. It is left over from the embryonic stage in the third week of gestation and functions as a reservoir. Scientists hypothesize that it may also have a role in fluid balance (6,8). This appendage can have differing morphologies or shapes in each client. The shapes are named Windsock, Cactus, Chicken Wing, and Cauliflower, as they are shaped similarly to these items (3,8). Chicken wing is the most common shape, and Cauliflower is the most susceptible to AF (3).

Figure 2. Left Atrial Appendage (heartvalvesurgery.com)

We know that anticoagulants are the first line of therapy in AF, but some clients are unable to take them. The concern for anticoagulants is non-compliance, bleeding, and fall risk, especially in elderly clients (18). We know how well warfarin works; however, clients must have frequent blood work to ensure the INR is in range. It can be inconvenient, especially for those who are memory-impaired or need transportation to a lab. To protect these clients from stroke in AF, discoveries had to be made.

Other newer anticoagulants, such as apixaban and rivaroxaban, work as well as warfarin without the lab work. However, they are very costly, do not have antidotes, and clients may discontinue taking them because of cost (18).

For clients who cannot take anticoagulants for any reason, something else is needed to protect them from stroke. One of the procedures used is pulse field ablation, which targets tissues that cause arrhythmia (5). It has been used for decades, takes less time, and has a lower risk of tissue damage surrounding the area (5).

Scientists began looking for alternatives and discovered that LAA blockage is a possible solution. As discussed earlier, LAA is believed to have a role in fluid balance, as was witnessed in earlier cut-and-sew methods of closing the LAA (18). The thought was that if the LAA was where 90% of clots formed, it made sense to amputate, occlude, or ligate the LAA (2).

During coronary bypass surgery, the LAA is usually excised or closed off, preventing approximately 90%of clot formation and is especially significant for those clients with a history of AF (19).

Three different devices were designed to close the LAA: the percutaneous LAA transcatheter occlusion (PLATO), Amplatzer cardiac plug, and the Watchman (2). The Watchman has proven to be the most beneficial and safest device (3). The Watchman is the size of a quarter and resembles a parachute. It is made with light and compact materials. It fits snugly over the LAA to permanently close it. The Watchman is inserted over a sheath through catheterization of a peripheral vein. Once inserted, it impedes blood clots’ entry into the heart.

During trials of the Watchman, it worked as well as warfarin without the hassle of regular lab work. It is used in clients with non-valvular AF and late ischemic events such as strokes (7,9).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How do you educate clients about bleeding if they are on an anticoagulant?

- How would you assist a client needing lab work without transportation?

- What is the material used in the Wachman?

- Can you find statistics on Watchman use as opposed to other treatments?

Watchman’s Risks and Successes

There are always issues or concerns when using a new medical drug or device, and the Watchman is no different. Usually, an electrophysiologist is the provider who performs the implant. They must know the problems that could occur, the shape of the LAA, and ensure the correct shaped device is utilized (6). The most severe complication is pericardial effusion. It has happened between 0.29% to 4.8% of implants in the early years. However, the numbers have decreased because of the many implants done and the furthering of education for the providers (2). It is a very challenging procedure as the LAA is very thin-walled, is damaged easily, and can result in cardiac tamponade or pericardial bleeding (2). Sometimes, during implantation, a clot in the LAA or L atrium can get dislodged and cause a stroke. However, the risk for that is 1%.

A registry from the perspective of real-world trials called EWOLUTION on Watchman showed a lower rate of stroke, trans ischemic attack (TIA), and side effects. Device-related thrombosis is the most concerning side effect, and anticoagulants are needed after implantation to ensure that no thrombus is present. The Watchman is also used for clients with a-fib who cannot take or who failed warfarin, apixaban, and rivaroxaban; however, anticoagulants are used for 45 days with a follow-up TEE that shows no residual effects (3). Warfarin may be discontinued then, aspirin and clopidogrel will be taken for 6 months, followed by aspirin 81 mg indefinitely (3).

Currently, the Watchman has shown long-term superiority over chronic warfarin. Scientists are still unsure why, but by 28 days post-implant, new endothelial tissue covered the Watchman device entirely. More research must be done to understand if the Watchman is beneficial in the long-term.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you find more information on the EWOLUTION registry?

- What information does a provider need about the client’s history before implantation?

- Can you find information on other devices besides the Watchman?

- How long does the Watchman procedure take?

Research

There are several trials ongoing for the Watchman. The ASAP-TOO is a study that evaluates the efficacy and safety of the Watchman with or without aspirin prior to the procedure (3). The CHAMPION-AF trial evaluates the LAA with the Watchman versus the newer drugs to reduce stroke without bleeding risk (3). The AMULET IDE trial evaluated the safety and efficacy of another implant, the AMPLATZER, versus the Watchman. This study states that the AMPLATZER is not inferior to the Watchman, but has one advantage. It has a double seal mechanism providing immediate and complete occlusion of the LAA (3).

The most appropriate anticoagulant management following Watchman placement has not been completely determined; however, warfarin and aspirin are the most commonly used agents at this time (3).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you locate any of these studies and learn their outcomes?

- Why would a provider use one device over another?

- If the AMPLATZER has an advantage of two layers over the Watchman, why is the Watchman used most often?

- Are there any other studies out there on LAA closure that you can find?

Conclusion

We have reviewed the LAA and AF extensively, the anatomy of the LAA, and its location in the heart. We know it is an appendage left over from the embryonic stage of three weeks. We discussed the different shapes of the LAA and how providers must understand and work with those shapes. We have also examined the prevalence of AF and how it has traditionally been treated. Newer types of anticoagulants are being used instead of warfarin because no lab work needs to be done. Lastly, we reviewed the Watchman, what it is made of, and how it fits the LAA for closure and blood clot prevention.

Researchers continue to study the efficacy and safety of other devices and medications. Although the Watchman is the most utilized device in non-valvular AF, research continues to seek to improve or develop new devices that work as well as or better than the Watchman.

References + Disclaimer

- Etumuse, B., & Miles, B. (2023). Association between rates of ischemic stroke and all-cause mortality with the Watchman device compared to warfarin and direct oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent)37(1), -5. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2023.2269354.

- Khan, S., Naz, H., Khan, M. S. Q., Ullah, A., Satti, D. I., Malik, J., & Mehmoodi, A. (2023). The WATCHMAN Device Review: A New Era for Stroke Prophylaxis. Journal of Community Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives, 13(3), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.55729/2000-9666.1183

- Magdi M, Renjithal SLM, Mubasher M, Mostafa MR, Lathwal Y, Mukuntharaj P, Mohamed S, Alweis R, Tan BE, Baibhav B. The WATCHMAN device and post-implantation anticoagulation management. A review of key studies and the risk of device-related thrombosis. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2021 Dec 15;11(6):714-722. PMID: 35116184; PMCID: PMC8784674.

- Brandes, A., M Crijns, J. G., Rienstra, M., Kirchhof, P., Grove, E. L., Pedersen, K. B., & 60Van Gelder, I. C. (2020). Cardioversion of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter revisited: Current evidence and practical guidance for a common procedure. Europace, 22(8), 1149-1161. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euaa057

- Joglar, J. A., Chung, M. K., Armbruster, A. L., Benjamin, E. J., Chyou, J. Y., Cronin, E. M., Deswal, A., Eckhardt, L. L., Goldberger, Z. D., Gopinathannair, R., Gorenek, B., Hess, P. L., Hlatky, M., Hogan, G., Ibeh, C., Indik, J. H., Kido, K., Kusumoto, F., Link, M. S., Linta, K. T., … Peer Review Committee Members (2024). 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation, 149(1), e1–e156. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001193

- Kubo, S., Mizutani, Y., Meemook, K., Nakajima, Y., Hussaini, A., & Kar, S. (2017). Incidence, characteristics, and clinical course of device-related thrombus after watchman left atrial appendage occlusion device implantation in atrial fibrillation patients. JACC. Clinical electrophysiology, 3(12), 1380–1386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2017.05.006

- Holmes, D. R., Jr, Kar, S., Price, M. J., Whisenant, B., Sievert, H., Doshi, S. K., Huber, K., & Reddy, V. Y. (2014). Prospective randomized evaluation of the Watchman Left Atrial Appendage Closure device in patients with atrial fibrillation versus long-term warfarin therapy: The PREVAIL trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 64(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.029

- Khan, S., Naz, H., Khan, M. S. Q., Ullah, A., Satti, D. I., Malik, J., & Mehmoodi, A. (2023). The WATCHMAN Device Review: A New Era for Stroke Prophylaxis. Journal of community hospital internal medicine perspectives, 13(3), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.55729/2000-9666.1183.

- Osmancik, P., Herman, D., Neuzil, P., Hala, P., Taborsky, M., Kala, P., Poloczek, M., Stasek, J., Haman, L., Branny, M., Chovancik, J., Cervinka, P., Holy, J., Kovarnik, T., Zemanek, D., Havranek, S., Vancura, V., Peichl, P., Tousek, P., Lekesova, V., … PRAGUE-17 Trial Investigators (2022). 4-Year outcomes after left atrial appendage closure versus nonwarfarin oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 79(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.10.0239.

- Staerk, L., Sherer, J. A., Ko, D., Benjamin, E. J., & Helm, R. H. (2017). Atrial fibrillation: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical outcomes. Circulation research, 120(9), 1501–1517. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.309732

- Nesheiwat, Z., Goyal, A., & Jagtap, M. (2023, April 26). Atrial fibrillation. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526072/

- Nayak, S., Natarajan, B., & Pai, R. G. (2020). Etiology, Pathology, and Classification of Atrial Fibrillation. The International journal of angiology: Official publication of the International College of Angiology, Inc, 29(2), 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1705153

- Li, J., Zhang, M., Gao, M., Liu, D., Li, Z., Du, J., & Hou, Y. (2020). Treatment of atrial fibrillation: A comprehensive review and practice guide. Cardiovascular Journal of Africa, 31(3), 153-158. https://doi.org/10.5830/CVJA-2019-064

- Mattia, A., Newman, J., & Manetta, F. (2020). Treatment complications of atrial fibrillation and their management. Int J Angiol, 29(2), 98-107. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-3401794.

- Roerecke M. (2021). Alcohol’s impact on the cardiovascular system. Nutrients, 3(10), 3419. doi: 10.3390/nu13103419.

- Li J, Gao M, Zhang M, Liu D, Li Z, Du J, Hou Y. (2020). Treatment of atrial fibrillation: A comprehensive review and practice guide. Cardiovasc J Afr. (3):153-158. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2019-064.

- Brandes, A., M, Crijns, J. G., Rienstra, M., Kirchhof, P., Grove, E. L., Pedersen, K. B., & Van Gelder, I. C. (2020). Cardioversion of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter revisited: Current evidence and practical guidance for a common procedure. Europace, 22(8), 1149-1161. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euaa057

- Arora, Y., Jozsa, F., & Soos, M. P. (2023). Anatomy, thorax, heart left atrial appendage. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553218/

- Janse, M. J. (n.d.). European Cardiac Arrythmia Society. https://ecas-heartrhythm.org/arial-fibrillation/

- Yadava, M. (2015). Atrial fibrillation: A timeline of this veritable quandary. American College of CARDIOLOGY. https://www.acc.org/membership/sections-and-councils/fellows-in-training-section/section-updates/2015/12/15/16/58/atrial-fibrillation

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate