Course

West Virginia APRN Bundle

Course Highlights

- In this West Virginia APRN Bundle course, we will learn about hypertension treatment clinical practice guidelines.

- You’ll also learn how to describe best practices for managing patients who display drug seeking behaviors and diversion.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of the six stages of pressure injuries based on National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel guidelines.

About

Pharmacology Contact Hours Awarded: 27

Course By:

Various Authors

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Hypertensive Agents

Introduction

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a common medical condition diagnosed and treated by healthcare professionals. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, around 34 million Americans are prescribed antihypertensive medications. Additionally, hypertension was a primary or contributing cause of more than 690,000 deaths in the United States in 2021 [6].

Healthcare providers must be knowledgeable of and follow current hypertension clinical practice guidelines. Understanding the different pharmacokinetics of antihypertensive medications is essential. This course outlines antihypertensive pharmacology and addresses pharmacokinetics, including mechanism of action, side effects, usage, and contraindications.

Definitions

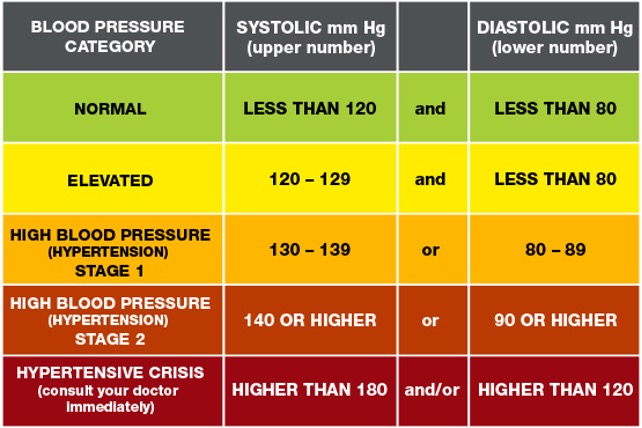

Hypertension – high blood pressure above normal. Normal is considered anything less than 120/80 mmHg [7].

Antihypertensives – medications used to control hypertension and lower blood pressure [7].

Hypertensive crisis – severely elevated blood pressure of either:

- Systolic greater than 180 mmHg

- Diastolic greater than 120 mmHg [19].

Hypertensive emergency – acutely elevated blood pressure with signs of target organ damage [2].

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is hypertension?

- What are antihypertensives?

- What is a hypertensive crisis?

- What is a hypertensive emergency?

Medications Overview

Antihypertensive medications are used for the treatment of hypertension and are used in both inpatient, outpatient, and emergency settings.

Some of the major antihypertensive medication classes include:

- Diuretics

- Beta-blockers

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

- Angiotensin II receptor blockers

- Calcium channel blockers

- Selective alpha-1 blockers

- Alpha-2 Receptor Agonists

- Vasodilators [3].

Different medical organizations have varying recommendations and hypertension treatment guidelines. Hypertension treatment clinical practice guidelines are available from organizations like the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the European Society of Cardiology to name a few [21]. Healthcare providers should be aware of their healthcare institution’s recommendations for clinical practice guidelines and organizations.

All organizational guidelines share the same recommended treatment of starting antihypertensives immediately when:

- Blood pressure is greater than 140/90 mmHg for patients with a history of ischemic heart disease, heart failure, or cerebrovascular disease.

- Blood pressure is greater than 160/100 mmHg regardless of underlying medical conditions [21].

Again, healthcare providers should follow current and evidence-based clinical guidelines for initiating or titrating antihypertensive medications.

While most antihypertensives are prescribed in an outpatient setting, certain antihypertensives are indicated during hypertensive or medical emergencies. For example, intravenous (IV) vasodilators, like nitroprusside and nitroglycerin, and calcium channel blockers, like nicardipine, are used during hypertensive emergencies and crises.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- In what settings are antihypertensives used?

- What are the clinical guidelines for initiating hypertensive medications?

- Which medications are commonly used to treat hypertensive emergencies?

Pharmacokinetics

Diuretics

Diuretics are a class of drugs that help control blood pressure by removing excess sodium and water from the body through the kidneys. There are several varying types of diuretics, some including thiazide, potassium-sparing, and loop, and all work to lower blood pressure differently [3].

Thiazide Diuretics

Thiazide diuretics remove excess sodium and water from the body by blocking the sodium-chloride (Na-Cl) channels in the kidneys’ distal convoluted tubule. As the Na-Cl channel becomes blocked, this inhibits the reabsorption of sodium and water into the kidneys. Concurrently, this causes a loss of potassium and calcium ions through the sodium-calcium channels and sodium-potassium pump [1].

Thiazide diuretics are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for controlling primary hypertension and are available via oral route. Some common thiazide diuretics are hydrochlorothiazide, chlorthalidone, and metolazone [3].

When initiating this medication, the healthcare provider should start with the lowest dose, which is usually 25mg daily, and then increase accordingly to aid with blood pressure control or if the patient has excess fluid retention, usually as evidenced by leg swelling or edema [1].

Common side effects of thiazide diuretics include:

- Increased urination

- Diarrhea

- Headache

- Stomach and muscle aches [16].

As thiazide diuretics interfere with Na-Cl, Na-Ca, and Na-K channels, there is an increased potential for adverse effects, including:

- Hypotension

- Hypokalemia

- Hyponatremia

- Hypercalcemia

- Hyperglycemia

- Hyperlipidemia

- Hyperuricemia

- Acute pancreatitis

When prescribing thiazide diuretics, healthcare providers should avoid prescribing thiazide diuretics to patients with a sulfonamide allergy, since thiazides are sulfa-containing medications. Also, they should avoid prescribing these to patients with a history of gout [1].

Additionally, patients can experience a thiazide overdose if they take more than the amount prescribed. Patients with a suspected overdose may experience confusion, dizziness, hypotension, and other symptoms. These patients must seek emergency care and poison control must be alerted [16].

Potassium-Sparing Diuretics

Potassium-sparing diuretics remove excess sodium and water from the body without causing loss of potassium. Depending on the type, they interrupt sodium reabsorption by either binding to epithelial sodium channels or inhibiting aldosterone receptors. When catatonic sodium is reabsorbed, this creates a negative gradient causing the reabsorption of potassium ions through the mineralocorticoid receptor [5].

Potassium-sparing diuretics are approved for controlling hypertension and are usually combined with other diuretics, like thiazide or loop diuretics since they have a weak antihypertensive effect.

Common names of potassium-sparing diuretics are amiloride, triamterene, and spironolactone. These medications are available by either intravenous or oral routes. Spironolactone is commonly used for treating primary aldosteronism and heart failure [5]. Patients should be started on the lowest dose when first prescribing this class of medications.

Common side effects can include:

- Increased urination

- Hyperkalemia

- Metabolic acidosis

- Nausea

[4]

Healthcare providers should avoid prescribing this class of medications to patients with hyperkalemia or chronic kidney disease. They should also be avoided during pregnancy or in patients who are taking digoxin. Since potassium-sparing medications can cause hyperkalemia, periodic monitoring for electrolyte imbalances and potassium levels is necessary [4].

Loop Diuretics

Loop diuretics inhibit sodium and chloride reabsorption by competing with chloride binding in the Na-K-2Cl (NKCC2) cotransporter. Potassium is not reabsorbed by the kidney, which causes additional calcium and magnesium ion loss.

Loop diuretics are FDA-approved for the treatment of hypertension but are not considered first-line treatment. They can also be used for treating fluid overload in conditions like heart failure or nephrotic syndrome [12].

Loop diuretics are available via oral or IV routes and furosemide, torsemide, and bumetanide are common forms [3].

Bioavailability and dosage differ for each type and route of loop diuretics. The bioavailability of furosemide is 50%, with a half-life of around 2 hours for patients with normal kidney function, and dosages start at 8mg for oral medication. Torsemide has a bioavailability of about 80%, a half-life of about 3 to 4 hours, and oral dosages start at 5mg [12].

Common side effects can include:

- Dizziness

- Increased urination

- Headache

- Stomach upset

- Hyponatremia

- Hypokalemia [13].

Loop diuretics can lead to several adverse effects, including toxicity, electrolyte imbalances, hyperglycemia, and ototoxicity. They have a black box warning stating that high dosages can cause severe diuresis. Therefore, electrolytes, BUN, and creatinine values should be monitored closely by a healthcare provider.

People with a sulfonamide allergy may also be allergic to loop diuretics, so this should be avoided if the patient is allergic. Loop diuretics also interfere with digoxin and therefore should be avoided. Other contraindications include anuria, hepatic impairments, and use during severe electrolyte disturbances [12].

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is the pharmacokinetics of thiazide diuretics?

- What is the pharmacokinetics of loop diuretics?

- What is the pharmacokinetics of potassium-sparing diuretics?

- What are common side effects and contraindications for each type of diuretic?

Beta-Blockers

Beta-blockers work by reducing the body’s heart rate and thus, lowering cardiac output resulting in lowered blood pressure [3]. The mechanism of action for beta-blockers varies, depending on the receptor type it blocks, and are classified as either non-selective or beta-1 (B1) selective.

Non-selective beta-blockers bind to the B1 and B2 receptors, blocking epinephrine and norepinephrine, causing a slowed heart rate. Propranolol, labetalol, and carvedilol are common non-selective beta-blockers.

Alternatively, beta-1 selective blockers only bind to the B1 receptors of the heart, so they are considered cardio-selective. Some examples include atenolol, metoprolol, and bisoprolol. Sotalol is a type of beta-blocker that also blocks potassium channels and is, therefore, a class III antiarrhythmic [8].

Beta-blockers are not primarily used for the initial treatment of hypertension but can be prescribed for conditions like tachycardia, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and cardiac arrhythmias. It’s also approved for use in conditions such as essential tremors, hyperthyroidism, glaucoma, and prevention of migraines.

Beta-blockers are available in many forms, including oral, IV, intramuscular injection, and ophthalmic drops. Starting dosage and route are determined by the health condition being treated [8].

Common side effects of beta-blockers include:

- Bradycardia

- Hypotension

- Dizziness

- Feeling tired

- Nausea

- Dry mouth

- Sexual Dysfunction

[17]

This class of medications can also lead to more severe adverse effects such as orthostatic hypotension, bronchospasm, shortness of breath, hyperglycemia, and increased risk of QT prolongation, torsades de pointes, and heart block [8]. Healthcare providers should avoid prescribing non-selective beta-blockers to patients with asthma. Instead, they can prescribe cardio-selective beta-blockers for patients with asthma.

Additionally, the use of beta-blockers is contraindicated in patients with a history of bradycardia, hypotension, Raynaud disease, QT prolongation, or torsades de pointes. Healthcare providers must encourage patients to monitor their heart rate and blood pressure and follow administration parameters before taking beta-blockers daily since it decreases their heart rate.

Overdose of beta-blockers is life-threatening and healthcare providers must discuss the symptoms of an overdose and the need for emergency care [8].

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is the pharmacokinetics of beta-blockers?

- What are the common side effects and contraindications of beta-blockers?

Angiotensin-converting Enzyme Inhibitors

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors prevent the body from producing angiotensin, a hormone that causes vasoconstriction. As angiotensin production is reduced, this allows the blood vessels to dilate and therefore lowers blood pressure [3].

Moreover, ACE inhibitors act specifically on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) by preventing the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II. It also works to decrease aldosterone, which in turn, decreases sodium and water reabsorption [9].

ACE inhibitors usually end in the suffix -pril and some common examples include lisinopril, benazepril, enalapril, and captopril, and they usually end in the suffix [3].

While ACE inhibitors are approved for treating hypertension, they are also FDA-approved for other uses or combination therapies for medical conditions such as:

- Systolic heart failure

- Chronic kidney disease

- ST-elevated myocardial infarction

One non-approved FDA use is treatment of diabetic nephropathy [9]. This class of medication is available in oral, and IV forms, and dosages are dependent on clinical guidelines, underlying medical conditions, and route.

ACE inhibitors have common side effects, with some including:

- Dry cough

- Dizziness

- Hypotension [9].

This medication can also lead to adverse effects, such as syncope, angioedema, and hyperkalemia [9]. As angioedema is an adverse effect, healthcare providers should understand this class of medications is contraindicated in patients with a history of hypersensitivity to ACE inhibitors.

Additionally, ACE inhibitors are contraindicated in patients with aortic valve stenosis, hypovolemia, and during pregnancy. Individuals with abnormal kidney function should have renal function and electrolyte values monitored. If a patient develops a chronic dry cough, then the healthcare provider should consider another antihypertensive medication class by following current guidelines [9].

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is the pharmacokinetics of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors?

- What are common side effects and contraindications of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors?

Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers

Similar to ACE inhibitors, Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers (ARBs) act on the RAAS by binding to angiotensin II receptors and thus block and reduce the action of angiotensin II. Again, this reduces blood pressure by causing blood vessel dilation and decreasing sodium and water reabsorption [11]. ARBs typically end in the suffix -artan and common names are losartan, valsartan, and Olmesartan [3]. Oral and IV routes of the medication are available and again, dosages are dependent on the medication specifically and form [11].

All ARBs are FDA-approved for the treatment of hypertension, but a select few are approved for treating other medical conditions, such as:

- Candesartan for heart failure

- Irbesartan for diabetic nephropathy

- Losartan for proteinuria and diabetic nephropathy

- Telmisartan for stroke and myocardial infarction prevention

- Valsartan for heart failure and reduction of mortality in patients with left ventricular dysfunction [11].

Although not as common as ACE inhibitors, two side effects of ARBs are dry cough and angioedema.

Other common side effects include:

- Dizziness

- Hypotension

- Hyperkalemia

[11]

Contraindications for use are if the patient is pregnant or has renal impairment or failure. If a patient is on an ARB, the healthcare provider should closely monitor lab values for electrolyte imbalances and kidney function.

Additionally, if a patient is taking lithium, ARBs can increase lithium concentration and therefore, lithium blood concentration should be frequently checked [11].

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is the pharmacokinetics of angiotensin II receptor blockers?

- What are common side effects and contraindications of angiotensin II receptor blockers?

Calcium Channel Blockers

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs), also known as calcium channel antagonists, act by preventing calcium from entering the smooth vascular and heart muscles. In turn, this reduces heart rate and causes vasodilation [3].

They are further divided into two major categories, non-dihydropyridines and dihydropyridines, where there are differences in the mechanism of action. Non-dihydropyridines inhibit calcium from entering the heart’s sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes and thus cause a cardiac conduction delay and reduce cardiac contractility.

Alternatively, dihydropyridines do not directly affect the heart but do act as a peripheral vasodilator leading to lowered blood pressure. Both categories are metabolized by the CYP3A4 pathway [15].

Names of non-dihydropyridine CCBs are verapamil and diltiazem. Dihydropyridine CCBs typically end in the suffix -pine and common names are amlodipine and nicardipine. Both categories are available via oral and IV routes for administration. Oral dosages of non-dihydropyridine CCBs start at 30mg daily and dihydropyridine CCBs start at 30mg daily for immediate release [15].

Calcium channel blockers can be used to treat other medical conditions in addition to hypertension and include:

- Coronary spasm

- Angina pectoris

- Supraventricular dysrhythmias

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Non-dihydropyridine CCBs can cause side effects like bradycardia, and constipation, while dihydropyridine CCBs can cause:

- Headaches

- Feeling lightheaded

- Leg swelling [15].

Both categories pose the risk of potential hypotension and bradycardia, so healthcare providers should closely monitor the patient’s blood pressure and heart rate when initiating or titrating the dosage.

Also, an overdose of this medication can lead to cardiac conduction delays, complete heart block, and cardiovascular collapse. Patients with possible symptoms of overdose should be sent to the emergency room immediately.

Additionally, healthcare providers should avoid prescribing CCBs to people with heart failure and sick sinus syndrome [15].

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is the pharmacokinetics of calcium channel blockers?

- What are the common side effects and contraindications of calcium channel blockers?

Selective Alpha-1 Blockers

Selective alpha-1 blockers act on the body’s sympathetic nervous system to lower blood pressure. They prevent norepinephrine from binding to the alpha-1 receptors of the sympathetic nervous system, causing smooth muscle relaxation and vasodilation which leads to lowered blood pressure [18].

Selective alpha-1 blockers are available via the oral route, end in the suffix -osin and examples are doxazosin, terazosin, and prazosin [3]. They are FDA-approved for the treatment of hypertension but are not considered first-line therapy. Additionally, this class of medications may be used to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia. Dosages can start as low as 1mg daily depending on the drug selected.

Common side effects include:

- Hypotension

- Tachycardia

- Dizziness

- Headache

- Weakness [18].

As selective alpha-1 blockers can lead to orthostatic hypotension, the healthcare provider should instruct the patient to take this medication at night. They should also avoid prescribing to the elderly population when able because of hypotension and increased fall risk [18].

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is the pharmacokinetics of alpha-1 blockers?

- What are the common side effects and contraindications of alpha-1 blockers?

Alpha-2 Receptor Agonists

Alpha-2 receptor agonists work by decreasing the activity of the sympathetic nervous system to lower blood pressure. It inhibits adenylyl cyclase and decreases the formation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). Alpha-2 agonists also cause vasodilation by reducing the amount of available cytoplasmic calcium [20].

This class of medications is typically administered via oral route but is also available in intravenous and transdermal forms. Two FDA-approved alpha-2 agonists for hypertension treatment are methyldopa and clonidine and dosages are dependent on the name and route.

Methyldopa is commonly prescribed to patients with hypertension and who are pregnant since it’s safe [20].

Common side effects of alpha-2 receptor agonists are:

- Dry mouth

- Drowsiness

- Fatigue

- Headache

- Sexual dysfunction [3].

Contraindications for use are orthostatic hypotension and autonomic disorders. Healthcare providers must avoid prescribing alpha-2 receptor agonists to individuals taking phosphodiesterase inhibitors [20].

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is the pharmacokinetics of alpha-2 receptor agonists?

- What are common side effects and contraindications of alpha-2 receptor agonists?

Vasodilators

Vasodilators lower blood pressure by dilating the body’s blood vessels. It binds to the receptors of the blood vessel’s endothelial cells, releasing calcium. Calcium stimulates nitric oxide synthase (NO synthase), eventually converting to L-arginine to nitric oxide. As nitric oxide is available, this allows for GTP to convert to cGMP, and causes dephosphorylation of the myosin and actin filaments. As this occurs, the blood vessels’ smooth muscles relax, leading to vasodilation and lowered blood pressure.

Common vasodilators that act via this pathway are nitrates and minoxidil. Hydralazine is another vasodilator, but the mechanism of action is unknown [10].

Available forms of vasodilators are sublingual, oral, and intravenous. Similar to other classes of antihypertensives, vasodilator dosages depend on the form and treatment setting [10].

Nitrovasodilators like nitroprusside and nitroglycerin are used during hypertensive emergencies. Hydralazine is used for severe hypertension for the prevention of eclampsia or intracranial hemorrhage and minoxidil for resistant hypertension [10] [3].

Side effects for each will vary, but nitrates commonly cause:

- Reflex tachycardia

- Headache

- Orthostatic hypotension

[10]

Common side effects of hydralazine are headaches, heart palpitations, and myalgias. Minoxidil causes excessive hair growth, weight gain, and fluid retention [3]. Additionally, nitroprusside can potentially cause cyanide toxicity.

Vasodilators have varying degrees of contraindications, such as nitrates are avoided in patients with an inferior myocardial infarction. Hydralazine should not be given to patients with coronary artery disease, angina, or rheumatic heart disease. Healthcare providers should be aware of contraindications and monitor patients’ blood pressure and potential side effects [10].

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is the pharmacokinetics of vasodilators?

- What are the common side effects and contraindications of vasodilators?

Combination Antihypertensives

Many antihypertensive medications come in combined forms, such as ACE inhibitors and thiazide diuretics, beta-blockers and diuretics, or calcium channel blockers and ACE inhibitors. The mechanism of action for combination antihypertensives depends on the blend of medications [3].

Considerations for Prescribers

This section reviews potential considerations when prescribing antihypertensives.

When prescribing antihypertensive medications, there are several factors that healthcare providers must consider. The route is typically determined by the healthcare setting and dosage by the underlying treatment goals. Again, healthcare providers should follow current guidelines when initiating or titrating antihypertensive medications.

Healthcare providers must complete a thorough health history, and review lab values, and contraindications as mentioned above. Monitoring kidney function and electrolyte values is imperative while any patient is taking antihypertensive medications.

While a single antihypertensive medication is recommended for initial treatment, there are some scenarios where combination therapy or combination antihypertensives are recommended [14].

Healthcare providers should also discuss the potential side effects of antihypertensives with patients and what to do if they are experiencing symptoms. For instance, if a patient reports syncope, they should be advised to go to the emergency room or be seen immediately for further evaluation. Also, healthcare providers must encourage patients to monitor their heart rate and blood pressure at home and abide by administration parameters.

For example, instruct patients who are taking beta-blockers to measure their blood pressure and heart rate before taking their medication. If their heart rate is below 60 beats per minute, then they should not take the medication [14].

If a patient is experiencing side effects from an antihypertensive medication, then another alternative should be selected.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What factors should healthcare providers consider when prescribing antihypertensives?

Upcoming Research

This section reviews upcoming research and medications for hypertension treatment.

Research on antihypertensive medications has slowed throughout the years. Some clinical trials were performed on the potential of endothelin receptor antagonists to reduce hypertension. However, some studies found several unwanted side effects, and thus clinical use was stopped for safety reasons.

An endothelin-A and endothelin-B receptor blocker, called aprocinentan, has shown promise for the treatment of resistant hypertension by lowering blood pressure and decreasing vascular resistance.

Research on sodium-glucose transport protein (SGLT2) inhibitors, which are typically used for the treatment of type II diabetes mellitus, is also ongoing. SGLT2 inhibitors may promote blood pressure reduction through diuresis and reduce sympathetic tone [21].

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What new research is there about antihypertensives?

Conclusion

If hypertension is left untreated, it can lead to serious health complications, including death. When selecting antihypertensive treatment, healthcare providers should understand the pharmacokinetics of each drug class along with potential side effects and contraindications. They should also follow current clinical guidelines for an evidence-based approach.

Final Reflection Questions

- Which antihypertensive medication is often prescribed during pregnancy?

- Which lab values are important when monitoring patients on each antihypertensive medication?

- Which antihypertensive medications cause hypokalemia?

- Which antihypertensive medications cause hyperkalemia?

Controlled Substances: A comprehensive review

Introduction

Pain is complex and subjective. The experience of pain can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life. According to the National Institute of Health (NIH) (40), pain is the most common complaint in a primary care office, with 20% of all patients reporting pain. Chronic pain is the leading cause of disability, and effective pain management is crucial to health and well-being, particularly when it improves functional ability. Effective pain treatment starts with a comprehensive, empathic assessment and a desire to listen and understand. Nurse Practitioners are well-positioned to fill a vital role in providing comprehensive and empathic patient care, including pain management (23).

While the incidence of chronic pain has remained a significant problem, how clinicians manage pain has significantly changed in the last decade, primarily due to the opioid epidemic. This education aims to discuss pain and the assessment of pain, federal guidelines for prescribing, the opioid epidemic, addiction and diversion, and recommendations for managing pain.

Definition of Pain

Understanding the definition of pain, differentiating between various types of pain, and recognizing the descriptors patients use to communicate their pain experiences are essential for Nurse practitioners involved in pain management. By understanding the medical definition of pain and how individuals may communicate it, nurse practitioners can differentiate varying types of pain to target assessment.

According to the International Association for the Study of Pain (27), pain is “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or terms of described such in damage.” The IASP, in July 2020, expanded its definition of pain to include context further.

Their expansion is summarized below:

- Pain is a personal experience influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors.

- Pain cannot be inferred solely from activity in sensory neurons.

- Individuals learn the concept of pain through their life experiences.

- A person’s report of an experience in pain should be respected.

- Pain usually serves an adaptive role but may adversely affect function and social and psychological well-being.

- The inability to communicate does not negate the possibility of the experience of pain.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Analyze how changes to the definition of pain may affect your practice.

- Discuss how you manage appointment times, knowing that 20% of your scheduled patients may seek pain treatment.

- How does the approach to pain management change in the presence of a person with a disability?

Types of Pain

Pain originates from different mechanisms, causes, and areas of the body. As a nurse practitioner, understanding the type of pain a patient is experiencing is essential for several reasons (23).

- Determining an accurate diagnosis. This kind of pain can provide valuable clues to the underlying cause or condition.

- Creating a treatment plan. Different types of pain respond better to specific treatments or interventions.

- Developing patient education. A nurse practitioner can provide targeted education to patients about their condition, why they may experience the pain as they do, its causes, and treatment options. Improving the patient's knowledge and control over their condition improves outcomes.

Acute Pain

Acute pain is typically short-lived and is a protective response to an injury or illness. Patients are usually able to identify the cause. This type of pain resolves as the underlying condition improves or heals (12).

Chronic Pain

Chronic pain is diagnosed when it continues beyond the expected healing time. Pain is defined as chronic when it persists for longer than three months. It may result from an underlying disease or injury or develop without a clear cause. Chronic pain often significantly impacts a person's physical and emotional well-being, requiring long-term management strategies. The prolonged experience of chronic pain usually indicates a central nervous system component of pain that may require additional treatment. Patients with centralized pain often experience allodynia or hyperalgesia (12).

Allodynia is pain evoked by a stimulus that usually does not cause pain, such as a light touch. Hyperalgesia is the effect of a heightened pain response to a stimulus that usually evokes pain (12).

Nociceptive Pain

Nociceptive pain arises from activating peripheral nociceptors, specialized nerve endings that respond to noxious stimuli. This type of pain is typically associated with tissue damage or inflammation and is further classified into somatic and visceral pain subtypes.

Somatic pain is most common and occurs in muscles, skin, or bones; patients may describe it as sharp, aching, stiffness, or throbbing.

Visceral pain occurs in the internal organs, such as indigestion or bowel spasms. It is more vague than somatic pain; patients may describe it as deep, gnawing, twisting, or dull (12).

Neuropathic pain

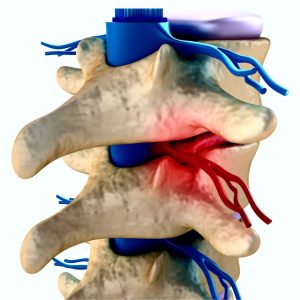

Neuropathic pain is a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system. Examples include trigeminal neuralgia, painful polyneuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, and central poststroke pain (10).

Neuropathic pain may be ongoing, intermittent, or spontaneous pain. Patients often describe neuropathic pain as burning, prickling, or squeezing quality. Neuropathic pain is a common chronic pain. Patients commonly describe allodynia and hyperalgesia as part of their chronic pain experience (10).

Affective pain

Affective descriptors reflect the emotional aspects of pain and include terms like distressing, unbearable, depressing, or frightening. These descriptors provide insights into the emotional impact of pain on an individual's well-being (12).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How can nurse practitioners effectively elicit patient descriptors to accurately assess the type of pain the patient is experiencing?

- Expand on how pain descriptors can guide interventions even if the cause is not yet determined.

- What strategies ensure patients feel comfortable describing their pain, particularly regarding subjective elements such as quality and location?

Case Study

Mary Adams is a licensed practical nurse who has just relocated to town. Mary will be the utilization review nurse at a local long-term care facility. Mary was diagnosed with Postherpetic Neuralgia last year, and she is happy that her new job will have her mostly doing desk work and not providing direct patient care as she had been before the relocation. Mary was having difficulty at work at her previous employer due to pain. She called into work several times, and before leaving, Mary's supervisor had counseled her because of her absences.

Mary wants to establish primary care immediately because she needs ongoing pain treatment. She is hopeful that, with her new job and pain under control, she will be able to continue a successful career in nursing. When Mary called the primary care office, she specifically requested a nurse practitioner as her primary care provider because she believes that nurse practitioners tend to spend more time with their patients.

Assessment

The assessment effectively determines the type of treatment needed, the options for treatment, and whether the patient may be at risk for opioid dependence. Since we know that chronic pain can lead to disability and pain has a high potential to negatively affect the patient's ability to work or otherwise, be productive, perform self-care, and potentially impact family or caregivers, it is imperative to approach the assessment with curiosity and empathy. This approach will ensure a thorough review of pain and research on pain management options. Compassion and support alone can improve patient outcomes related to pain management (23).

Record Review

Regardless of familiarity with the patient, reviewing the patient's treatment records is essential, as the ability to recall details is unreliable. Reviewing the records can help identify subtle changes in pain description and site, the patient's story around pain, failed modalities, side effects, and the need for education, all impacting further treatment (23).

Research beforehand the patient's current prescription and whether or not the patient has achieved the maximum dosage of the medication. Analysis of the patient's past prescription could reveal a documented failed therapy even though the patient did not receive the maximum dose (23).

A review of documented allergens may indicate an allergy to pain medication. Discuss with the patient the specific response to the drug to determine if it is a true allergy, such as hives or anaphylaxis, or if the response may have been a side effect, such as nausea and vomiting.

Research whether the patient tried any non-medication modalities for pain, such as physical therapy (PT), occupational therapy (OT), or Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). Note any non-medication modalities documented as failed therapies. The presence of any failed therapies should prompt further discussion with the patient, family, or caregiver about the experience. The incompletion of therapy should not be considered failed therapy. Explore further if the patient abandoned appointments.

Case Study

You review the schedule for the week, and there are three new patient appointments. One is Mary Adams. The interdisciplinary team requested and received Mary's treatment records from her previous primary care provider. You make 15 minutes available to review Mary's records and the questionnaire Mary filled out for her upcoming appointment. You see that Mary has been diagnosed with Postherpetic Neuralgia and note her current treatment regimen, which she stated was ineffective. You write down questions you will want to ask Mary. You do not see evidence of non-medication modalities or allergies to pain medication.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What potential risks or complications can arise from neglecting to conduct a thorough chart review before initiating a pain management assessment?

- In your experience, what evidence supports reviewing known patient records?

- What is an alternative to reviewing past treatment if records are not available?

Pain Assessment

To physically assess pain, several acronyms help explore all the aspects of the patient's experience. Acronyms commonly used to assess pain are SOCRATES, OLDCARTS, and COLDERAS. These pain assessment acronyms are also helpful in determining treatment since they include a character and duration of pain assessment (23).

| O-Onset | S-Site | C-Character |

| L-Location | O-Onset | O-Onset |

| D-Duration | C-Character | L-Location |

| C-Character | R-Radiate | D-Duration |

| A-Alleviating | A-Associated symptoms | E-Exacerbating symptoms |

| R-Radiating, relieving | T-Time/Duration | R-Relieving, radiating |

| T-Temporal patterns (frequency) | E-Exacerbating | A-Associated symptoms |

| S-Symptoms | S-Severity | S-Severity of illness |

Inquire where the patient is feeling pain. The patient may have multiple areas and types of pain. Each type and location must be explored and assessed. Unless the pain is from a localized injury, a body diagram map, as seen below, is helpful to document, inform, and communicate locations and types of pain. In cases of Fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, or other centralized or widespread pain, it is vital to inquire about radiating pain. The patient with chronic pain could be experiencing acute pain or a new pain site, such as osteoarthritis, that may need further evaluation and treatment (23).

Inquire with the patient how long their pain has been present and any associated or known causative factors. Pain experienced longer than three months defines chronic versus acute pain. Chronic pain means that the pain is centralized or a function of the Central Nervous system, which should guide treatment decisions.

To help guide treatment, ask the patient to describe their pain. The description helps identify what type of pain the patient is experiencing: Allodynia and hyperalgesia indicate centralized pain; sharp, shooting pain could indicate neuropathic pain. Have the patient rate their pain. There are various tools, as shown below, for pain rating depending on the patient's ability to communicate. Not using the pain rating number alone is imperative. Ask the patient to compare the severity of pain to a previous experience. For example, a 1/10 may be experienced as a bumped knee or bruise, whereas a 10/10 is experienced on the level of a kidney stone or childbirth (23).

Besides the 0-10 rating scale and depending on the patient's needs, several pain rating scales are appropriate. They are listed below.

The 0-5 and Faces scales may be used for all adult patients and are especially effective for patients experiencing confusion.

The Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale (DVPRS) is a five-item tool that assesses the impact of pain on sleep, mood, stress, and activity levels (20).

For patients unable to self-report pain, such as those intubated in the ICU or late-stage neurological diseases, the FLACC scale is practical. The FLACC scale was initially created to assess pain in infants. Note: The patient need not cry to be rated 10/10.

| Behavior | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Face | No particular expression or smile | Occasional grimace or frown, withdrawn, disinterested | Frequent or constant quivering chin, clenched jaw |

| Legs | Normal position or relaxed | Uneasy, restless, tense | Kicking or legs drawn |

| Activity | Lying quietly, in a normal position, or relaxed | Squirming, shifting back and forth, tense | Arched, rigid, or jerking |

| Cry | No cry wake or asleep | Moans or whimpers: occasional complaints | Crying steadily, screams, sobs, frequent complaints |

| Consolability | Content, relaxed | Distractable, reassured by touching, hugging, or being talked to | Difficult to console or comfort |

(21).

Assess contributors to pain such as insomnia, stress, exercise, diet, and any comorbid conditions. Limited access to care, socioeconomic status, and local culture also contribute to the patient's experience of pain (23). Most patients have limited opportunity to discuss these issues, and though challenging to bring up, it is compassionate and supportive care. A referral to social work or another agency may be helpful if you cannot explore it fully.

Assess for substance abuse disorders, especially among male, younger, less educated, or unemployed adults. Substance abuse disorders increase the likelihood of misuse disorder and include alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, cocaine, and heroin (29).

Inquire as to what changes in function the pain has caused. One question to ask is, "Were it not for pain, what would you be doing?" As seen below, a Pain, Enjoyment, and General Activity (PEG) three-question scale, which focuses on function and quality of life, may help determine the severity of pain and the effect of treatment over time.

| What number best describes your pain on average in the past week? 0-10 |

| What number best describes how, in the past week, pain has interfered with your enjoyment of life? 0-10 |

| What number determines how, in the past week, pain has interfered with your general activity? 0-10 |

(21).

Assess family history, mental health disorders, chronic pain, or substance abuse disorders. Each familial aspect puts patients at higher risk for developing chronic pain (23).

Evaluate for mental health disorders the patient may be experiencing, particularly anxiety and depression. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ4) is a four-question tool for assessing depression and anxiety.

In some cases, functional MRI or imaging studies effectively determine the cause of pain and the treatment. If further assessment is needed to diagnose and treat pain, consult Neurology, Orthopedics, Palliative care, and pain specialists (23).

Case Study

You used OLDCARTS to evaluate Mary's pain and completed a body diagram. Mary is experiencing allodynia in her back and shoulders, described as burning and tingling. It is exacerbated when she lifts, such as moving patients at the long-term care facility and, more recently, boxes from her move to the new house. Mary has also been experiencing anxiety due to fear of losing her job, the move, and her new role. She has moved closer to her family to help care for her children since she often experiences fatigue. Mary has experienced a tumultuous divorce in the last five years and feels she is still undergoing some trauma.

You saw in the chart that Mary had tried Gabapentin 300 mg BID for her pain and inquired what happened. Mary explained that her pain improved from 8/10 to 7/10 and had no side effects. Her previous care provider discontinued the medication and documented it as a failed therapy. You reviewed the minimum and maximum dosages of Gabapentin and know Mary can take up to 1800mg/day.

During the assessment, Mary also described stiffness and aching in her left knee. She gets a sharp pain when she walks more than 500 steps, and her knee is throbbing by the end of the day. Mary rated the pain a 10/10, but when she compared 10/10 to childbirth, Mary said her pain was closer to 6/10. Her moderate knee pain has reduced Mary's ability to exercise. She used to like to take walks. Mary stated she has had knee pain for six months and has been taking Ibuprofen 3 – 4 times daily.

Since Mary's pain is moderate, you evaluate your options of drugs for moderate to severe pain.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How do you assess and evaluate a patient's pain level?

- What are the different types of pain and their management strategies?

- How do you determine the appropriate dosage of pain medications for a patient?

- How do you assess the effectiveness of pain medications in your patients?

- How do you adjust medication dosages for elderly patients with pain or addiction?

- How do you address the unique challenges in pain management for pediatric patients?

- What is the role of non-pharmacological interventions in pain management?

- How do you incorporate non-pharmacological interventions into your treatment plans?

Opioid Classifications and Drug Schedules

A comprehensive understanding of drug schedules and opioid classifications is essential for nurse practitioners to ensure patient safety, prevent drug misuse, and adhere to legal and regulatory requirements. Nurse practitioners with a comprehensive understanding of drug schedules and opioid classifications can effectively communicate with colleagues, ensuring accurate medication reconciliation and facilitating interdisciplinary care. Nurse practitioners’ knowledge in facilitating discussions with pharmacists regarding opioid dosing, potential interactions, and patient education is essential (49).

Drug scheduling became mandated under the Controlled Substance Act. The Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) Schedule of Controlled Drugs and the criteria and common drugs are listed below.

|

Schedule |

Criteria | Examples |

|

I |

No medical use; high addiction potential |

Heroin, marijuana, PCP |

|

II |

Medical use; high addiction potential |

Morphine, oxycodone, Methadone, Fentanyl, amphetamines |

|

III |

Medical use; high addiction potential |

Hydrocodone, codeine, anabolic steroids |

|

IV |

Medical use, low abuse potential |

Benzodiazepines, meprobamate, butorphanol, pentazocine, propoxyphene |

| V | Medical use; low abuse potential |

Buprex, Phenergan with codeine |

(Pain Physician, 2008)

Listed below are drugs classified by their schedule and mechanism of action. "Agonist" indicates a drug that binds to the opioid receptor, causing pain relief and also euphoria. An agonist-antagonist indicates the drug binds to some opioid receptors but blocks others. Mixed antagonist-agonist drugs control pain but have a lower potential for abuse and dependence than agonists (7).

| Schedule I | Schedule II | Schedule III | Schedule IV | Schedule V | |

| Opioid agonists |

BenzomorphineDihydromor-phone, Ketobemidine, Levomoramide, Morphine-methylsulfate, Nicocodeine, Nicomorphine, Racemoramide |

Codeine, Fentanyl, Sublimaze, Hydrocodone, Hydromorphone, Dilaudid, Meperidine, Demerol, Methadone, Morphine, Oxycodone, Endocet, Oxycontin, Percocet, Oxymorphone, Numorphan |

Buprenorphine Buprenex, Subutex, Codeine compounds, Tylenol #3, Hydrocodone compounds, Lortab, Lorcet, Tussionex, Vicodin |

Propoxyphene, Darvon, Darvocet | Opium, Donnagel, Kapectolin |

| Mixed Agonist -Antagonist | BuprenorphineNaloxone, Suboxone |

Pentazocine, Naloxone, Talwin-Nx |

|||

| Stimulants | N-methylampheta-mine 3, 4-methylenedioxy amphetamine, MDMA, Ecstacy | Amphetamine, Adderal, Cocaine, Dextroamphetamine, Dexedrine, Methamphetamine, Desoxyn, Methylphenidate, Concerta, Metadate, Ritalin, Phenmetrazine, Fastin, Preludin | Benapheta-mine, Didrex, Pemolin, Cylert, Phendimetra-zine, Plegine | Diethylpropion, Tenuate, Fenfluramine, Phentermine Fastin | 1-dioxy-ephedrine-Vicks Inhaler |

| Hallucinogen-gens, other | Lysergic Acid Diamine LSD, marijuana, Mescaline, Peyote, Phencyclidine PCP, Psilocybin, Tetrahydro-cannabinol | Dronabinol, Marinol | |||

| Sedative Hypnotics |

Methylqualine, Quaalude, Gamma-hydroxy butyrate, GHB

|

Amobarbitol, Amytal, Glutethamide, Doriden, Pentobarbital, Nembutal, Secobarbital, Seconal |

Butibarbital. Butisol, Butilbital, Florecet, Florinal, Methylprylon, Noludar |

Alprazolam, Xanax, Chlordiazepoxide, Librium, Chloral betaine, Chloral hydrate, Noctec, Chlorazepam, Clonazepam, Klonopin, Clorazopate, Tranxene, Diazepam, Valium, Estazolam, Prosom, Ethchlorvynol, Placidyl, Ethinamate, Flurazepam, Dalmane, Halazepam, Paxipam, Lorazepam, Ativan, Mazindol, Sanorex, Mephobarbital, Mebaral, Meprobamate, Equanil, Methohexital, Brevital Sodium, Methyl-phenobarbital, Midazolam, Versed, Oxazepam, Serax, Paraldehyde, Paral, Phenobarbital, Luminal, Prazepam, Centrax, Temazepam, Restoril, Triazolam, Halcion, Sonata, Zolpidem, Ambien |

Diphenoxylate preparations, Lomotil |

(41).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are the potential risks and benefits of using opioids for pain management?

- How can nurse practitioners effectively monitor patients on long-term opioid therapy?

- What are the potential risks and benefits of using long-acting opioids for chronic pain?

- How do you monitor patients on long-acting opioids for safety and efficacy?

Commonly Prescribed Opioids, Indications for Use, and Typical Side Effects

Opioid medications are widely used for managing moderate to severe pain. Referencing NIDA (2023), this section aims to give healthcare professionals an overview of the indications and typical side effects of commonly prescribed Schedule II opioid medications, including hydrocodone, oxycodone, morphine, Fentanyl, and hydromorphone.

Opioids are derived and manufactured in several ways. Naturally occurring opioids come directly from the opium poppy plant. Synthetic opioids are manufactured by chemically synthesizing compounds that mimic the effects of a natural opioid. Semi-synthetic is a mix of naturally occurring and man-made (35).

Understanding the variations in how an opioid is derived and manufactured is crucial in deciding the type of opioid prescribed, as potency and analgesic effects differ. Synthetic opioids are often more potent than naturally occurring opioids. Synthetic opioids have a longer half-life and slower elimination, affecting the duration of action and timing for dose adjustments. They are also associated with a higher risk of abuse and addiction (38).

Hydrocodone

Mechanism of Action and Metabolism

Hydrocodone is a Schedule II medication. It is an opioid agonist and works as an analgesic by activating mu and kappa opioid receptors located in the central nervous system and the enteric plexus of the bowel. Agonist stimulation of the opioid receptors inhibits nociceptive neurotransmitters' release and reduces neuronal excitability (17).

- Produces analgesia.

- Suppresses the cough reflex at the medulla.

- Causes respiratory depression at higher doses.

Hydrocodone is indicated for treating severe pain after nonopioid therapy has failed. It is also indicated as an antitussive for nonproductive cough in adults over 18.

Available Forms

Hydrocodone immediate release (IR) reaches maximum serum concentrations in one hour with a half-life of 4 hours. Extended-release (ER) Hydrocodone reaches peak concentration at 14-16 hours and a half-life of 7 to 9 hours. Hydrocodone is metabolized to an inactive metabolite in the liver by cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP2D6 and CYP3A4. Hydrocodone is converted to hydromorphone and is excreted renally. Plasma concentrations of hydromorphone are correlated with analgesic effects rather than hydrocodone.

Hydrocodone is formulated for oral administration into tablets, capsules, and oral solutions. Capsules and tablets should never be crushed, chewed, or dissolved. These actions convert the extended-release dose into immediate release, resulting in uncontrolled and rapid release of opioids and possible overdose.

Dosing and Monitoring

Hydrocodone IR is combined with acetaminophen or ibuprofen. The dosage range is 2.5mg to 10mg every 4 to 6 hours. If formulated with acetaminophen, the dosage is limited to 4gm/day.

Hydrocodone ER is available as tablets and capsules. Depending on the product, the dose of hydrocodone ER formulations in opioid-naïve patients is 10 to 20 mg every 12 to 24 hours.

Nurse practitioners should ensure patients discontinue all other opioids when starting the extended-release formula.

Side Effects and Contraindications

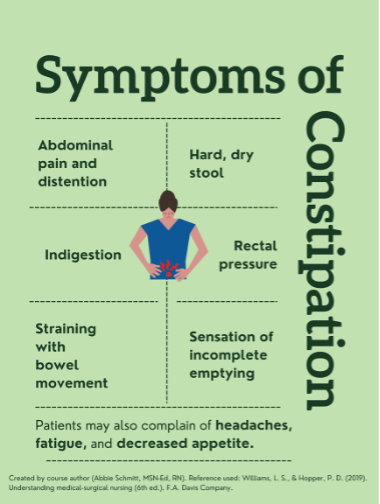

Because mu and kappa opioid receptors are in the central nervous system and enteric plexus of the bowel, the most common side effects of hydrocodone are constipation and nausea (>10%).

Other adverse effects of hydrocodone include:

- Respiratory: severe respiratory depression, shortness of breath

- Cardiovascular: hypotension, bradycardia, peripheral edema

- Neurologic: Headache, chills, anxiety, sedation, insomnia, dizziness, drowsiness, fatigue

- Dermatologic: Pruritus, diaphoresis, rash

- Gastrointestinal: Vomiting, dyspepsia, gastroenteritis, abdominal pain

- Genitourinary: Urinary tract infection, urinary retention

- Otic: Tinnitus, sensorineural hearing loss

- Endocrine: Secondary adrenal insufficiency (17)

Hydrocodone, being an agonist, must not be taken with other central nervous system depressants as sedation and respiratory depression can result. In formulations combined with acetaminophen, hydrocodone can increase the international normalized ratio (INR) and cause bleeding. Medications that induce or inhibit cytochrome enzymes can lead to wide variations in absorption.

The most common drug interactions are listed below:

- Alcohol

- Benzodiazepines

- Barbiturates

- other opioids

- rifampin

- phenytoin

- carbamazepine

- cimetidine,

- fluoxetine

- ritonavir

- erythromycin

- diltiazem

- ketoconazole

- verapamil

- Phenytoin

- John’s Wort

- Glucocorticoids

Considerations

Use with caution in the following:

- Patients with Hepatic Impairment: Initiate 50% of the usual dose

- Patients with Renal Impairment: Initiate 50% of the usual dose

- Pregnancy: While not contraindicated, the FDA issued a black-boxed warning since opioids cross the placenta, and prolonged use during pregnancy may cause neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS).

- Breastfeeding: Infants are susceptible to low dosages of opioids. Non-opioid analgesics are preferred.

Pharmacogenomic: Genetic variants in hydrocodone metabolism include ultra-rapid, extensive, and poor metabolizer phenotypes. After administration of hydrocodone, hydromorphone levels in rapid metabolizers are significantly higher than in poor metabolizers.

Oxycodone

Mechanism of Action and Metabolism

Oxycodone has been in use since 1917 and is derived from Thebaine. It is a semi-synthetic opioid analgesic that works by binding to mu-opioid receptors in the central nervous system. It primarily acts as an agonist, producing analgesic effects by inhibiting the transmission of pain signals (Altman, Clark, Huddart, & Klein, 2018).

Oxycodone is primarily metabolized in the liver by CYP3A4/5. It is metabolized in the liver to noroxycodone and oxymorphone. The metabolite oxymorphone also has an analgesic effect and does not inhibit CYP3A4/5. Because of this metabolite, oxycodone is more potent than morphine, with fewer side effects and less drug interactions. Approximately 72% of oxycodone is excreted in urine (Altman, Clark, Huddart, & Klein, 2018).

Available Forms

Oxycodone can be administered orally, rectally, intravenously, and as an epidural. For this sake, we will focus on immediate-release and extended-release oral formulations.

- Immediate-release (IR) tablets

- IR capsules

- IR oral solutions

- Extended-release (ER) tablets

Dosing and Monitoring

The dosing of oxycodone should be individualized based on the patient's pain severity, previous opioid exposure, and response. Initial dosages for opioid naïve patients range from 5-15 mg for immediate-release formulations, while extended-release formulations are usually initiated at 10-20 mg. Dosage adjustments may be necessary based on the patient's response, but caution should be exercised. IR and ER formulations reach a steady state at 24 hours and titrating before 24 hours may lead to overdose.

Regular monitoring is essential to assess the patient's response to treatment, including pain relief, side effects, and signs of opioid misuse or addiction. Monitoring should include periodic reassessment of pain intensity, functional status, and adverse effects (Altman, Clark, Huddart, & Klein, 2018).

Side Effects and Contraindications

Common side effects of oxycodone include:

- constipation

- nausea

- sedation

- dizziness

- respiratory depression

- respiratory arrest

- hypotension

- fatal overdose

Oxycodone is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to opioids, severe respiratory depression, paralytic ileus, or acute or severe bronchial asthma. It should be used cautiously in patients with a history of substance abuse, respiratory conditions, liver or kidney impairment, and those taking other medications that may interact with opioids, such as alcohol (4).

It is also contraindicated with the following medications and classes:

- Antifungal agents

- Antibiotics

- Rifampin

- Carbamazepine

- Fluoxetine

- Paroxetine

Considerations

- Nurse practitioners should consider the variations in the mechanism of action for the following:

- Metabolism differs between males and females: females have been shown to have less concentration of oxymorphone and more CYP3A4/5 metabolites.

- Infants have reduced clearance of oxycodone, increasing side effects.

- Pediatrics have 20-40% increased clearance over adults.

- Reduced clearance with age increases the half-life of oxycodone.

- Pregnant women have a greater clearance and reduced half-life.

- Impairment of the liver reduces clearance.

- Cancer patients with cachexia have increased exposure to oxycodone and its metabolite.

- Maternal and neonate concentrations are similar, indicating placenta crossing (4)

Morphine

Mechanism of Action and Metabolism

Morphine is a naturally occurring opioid alkaloid extracted from the opium poppy. It was isolated in 1805 and is the opioid against which all others are compared. Morphine binds to mu-opioid receptors in the brain and spinal cord, inhibiting the transmission of pain signals and producing analgesia. It is a first-line choice of opioid for moderate to severe acute, postoperative, and cancer-related pain (8).

Morphine undergoes first-pass metabolism in the liver and gut. It is well absorbed and distributed throughout the body. Its main metabolites are morphine-3-glucuronide and morphine-6-glucuronide. Its mean plasma elimination half-life after intravenous administration is about 2 hours. Approximately 90% of morphine is excreted in the urine within 24 hours (8).

Available Forms

Morphine is available in various forms, including.

- immediate-release tablets

- extended release tablets

- oral IR solutions

- injectable solutions

- transdermal patches

Dosing and Monitoring

Morphine is hydrophilic and, as such, has a slow onset time. The advantage of this is that it is unlikely to cause acute respiratory depression even when injected. However, because of the slow onset time, there is more likelihood of morphine overdose due to the ability to “stack” doses in patients experiencing severe pain (Bistas, Lopez-Ojeda, & Ramos-Matos, 2023).

The dosing of morphine depends on the patient's pain severity, previous opioid exposure, and other factors. It is usually initiated at a low dose and titrated upwards as needed. Monitoring pain relief, adverse effects, and signs of opioid toxicity is crucial. Reevaluate benefits and harms with patients within 1 to 4 weeks of starting opioid therapy or of dose escalation. General recommendations for initiating morphine (Bistas, Lopez-Ojeda, & Ramos-Matos, 2023).

Prescribe IR opioids instead of ER opioids.

Prescribe the lowest effective dosage, below 50 Morphine Milligram Equivalents (MME) /day.

Side Effects and Contraindications

Because morphine binds to opioid receptors in the brain and spinal cord, is metabolized in the liver and gut, and has a slow onset, the following side effects are common:

- Constipation

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Sedation

- Dizziness

- Respiratory depression

- Pruritis

- Sweating

- Dysphoria/Euphoria

- Dry mouth

- Anorexia

- Spasms of urinary and biliary tract

Contraindications of morphine are:

- Known hypersensitivity or allergy to morphine.

- Bronchial asthma or upper airway obstruction

- Respiratory depression in the absence of resuscitative equipment

- Paralytic ileus

- Risk of choking in patients with dysphagia, including infants, children, and the elderly (8)

Concurrent use with other sedating medications: Amitriptyline, diazepam, haloperidol, chlorpromazine

Morphine interacts with the following medications:

- Ciprofloxacin

- Metoclopramide

- Ritonavir

Considerations for Nurse Practitioners

Assess for medical conditions that may pose serious and life-threatening risks with opioid use, such as the following:

- Sleep-disordered breathing, such as sleep apnea.

- Pregnancy

- Renal or hepatic insufficiency

- Age >= 65

- Certain mental health conditions

- Substance use disorder

- Previous nonfatal overdose

Fentanyl

Mechanism of Action and Metabolism

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid more potent than morphine and was approved in 1968. Fentanyl is an agonist that works by binding to the mu-opioid receptors in the central nervous system. This binding inhibits the transmission of pain signals, resulting in analgesia. Fentanyl is often used for severe pain management, particularly in the perioperative and palliative care settings, or for severe pain in patients with Hepatic failure (8).

It is a mu-selective opioid agonist. However, it can activate other opioid receptors in the body, such as the delta and kappa receptors, producing analgesia. It also activates the Dopamine center of the brain, stimulating relaxation and exhilaration, which is responsible for its high potential for addiction (8).

Indications for fentanyl are as follows:

- Preoperative analgesia

- Anesthesia adjunct

- Regional anesthesia adjunct

- General anesthesia

- Postoperative pain control

- Moderate to severe acute pain (off-label)

Available Forms

- Fentanyl is available in various forms, including:

- transdermal patches

- injectable solutions

- lozenges

- nasal sprays

- oral tablets (8)

Dosing and Monitoring

Fentanyl is metabolized via the CYP3A4 enzyme in the liver. It has a half-life of 3 to 7 hours, and 75% of Fentanyl is excreted in the urine and 9% in feces.

The dosing of fentanyl depends on the route of administration and the patient's needs. For example, transdermal patches are typically applied every 72 hours, while injectable solutions are titrated to achieve the desired analgesic effect. Monitoring should include assessing pain levels, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and sedation scores (8).

Fentanyl is most dosed as follows:

- Post-operative pain control

- 50 to 100 mcg IV/IM every 1 to 2 hours as needed; alternately 0.5 to 1.5 mcg/kg/hour IV as needed. Consider lower dosing in patients 65 and older.

PCA (patient-controlled analgesia): 10 to 20 mcg IV every 6 to 20 minutes as needed; start at the lowest effective dose for the shortest effective duration - refer to institutional protocols (8).

Moderate to severe acute pain (off-label) 1 to 2 mcg/kg/dose intranasally each hour as needed; the maximum dose is 100 mcg. Use the lowest effective dose for the shortest effective duration (8).

Side Effects and Contraindications

Common side effects of fentanyl include:

- respiratory depression

- sedation

- constipation

- nausea

- vomiting

- euphoria

- confusion

- respiratory depression/arrest

- visual disturbances

- dyskinesia

- hallucinations

- delirium

- narcotic ileus

- muscle rigidity

- addiction

- loss of consciousness

- hypotension

- coma

- death (8).

The use of fentanyl is contraindicated in patients in the following situations:

- After operative interventions in the biliary tract, these may slow hepatic elimination of the drug.

- With respiratory depression or obstructive airway diseases (i.e., asthma, COPD, obstructive sleep apnea, obesity hyperventilation, also known as Pickwickian syndrome)

- With liver failure

- With known intolerance to fentanyl or other morphine-like drugs, including codeine or any components in the formulation.

- With known hypersensitivity (i.e., anaphylaxis) or any common drug delivery excipients (i.e., sodium chloride, sodium hydroxide) (8).

Considerations for Nurse Practitioners

Nurse practitioners prescribing fentanyl should thoroughly assess the patient's pain, medical history, and potential risk factors for opioid misuse. They should also educate patients about the proper use, storage, and disposal of fentanyl. It should be used cautiously in patients with respiratory disorders, liver or kidney impairment, or a history of substance abuse. Fentanyl is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to opioids and those without exposure to opioids.

Alcohol and other drugs, legal or illegal, can exacerbate fentanyl's side effects, creating multi-layered clinical scenarios that can be complex to manage. These substances, taken together, generate undesirable conditions that complicate the patient's prognosis (8).

Hydromorphone

Mechanism of Action and Metabolism

Hydromorphone is a semi-synthetic opioid derived from morphine. It binds to the mu-opioid receptors in the central nervous system. It primarily exerts its analgesic effects by inhibiting the release of neurotransmitters involved in pain transmission, thereby reducing pain perception. Hydromorphone also exerts its effects centrally at the medulla level, leading to respiratory depression and cough suppression (1).

Hydromorphone is indicated for:

- moderate to severe acute pain

- severe chronic pain

- refractory cough suppression (off-label) (1)

Available Forms

Hydromorphone is available in various forms, depending on the patient’s needs and severity of pain.

- immediate-release tablet

- extended release tablets

- oral liquid

- injectable solution

- rectal suppositories

Dosing and Monitoring

The immediate-release oral formulations of hydromorphone have an onset of action within 15 to 30 minutes. Peak levels are typically between 30 and 60 minutes with a half-life of 2 to 3 hours. Hydromorphone is primarily excreted through the urine.

The dosing of hydromorphone should be individualized based on the patient's pain intensity, initiated at the lowest effective dose, and adjusted gradually as needed. Close monitoring of pain relief, adverse effects, and signs of opioid toxicity is essential. Patients should be assessed regularly to ensure they receive adequate pain control without experiencing excessive sedation or respiratory depression.

The following are standard dosages that should only be administered when other opioid and non-opioid options fail.

- Immediate-release oral solutions dosage: 1 mg/1 mLoral tablets are available in 2 mg, 4 mg, and 8 mg.

- Extended-release oral tablets are available in dosages of 8 mg, 12 mg, 16 mg, and 32 mg.

- Injection solutions are available in concentrations of 1 mg/mL, 2 mg/mL, 4 mg/mL, and 10 mg/mL.

- Intravenous solutions are available in strengths of 2 mg/1 mL, 2500 mg/250 mL, ten mg/1 mL, and 500 mg/50 mL.

- Suppositories are formulated at a strength of 3 mg (1).

Side Effects and Contraindications

Hydromorphone has potential adverse effects on several organ systems, including the integumentary, gastrointestinal, neurologic, cardiovascular, endocrine, and respiratory.

Common side effects of hydromorphone include:

- Constipation

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Dizziness

- Sedation

- respiratory depression

- pruritus

- headache

- Somnolence

- Severe adverse effects of hydromorphone include:

- Hypotension

- Syncope

- adrenal insufficiency

- coma

- raised intracranial pressure.

- seizure

- suicidal thoughts

- apnea

- respiratory depression or arrest

- drug dependence or withdrawal

- neonatal drug withdrawal syndrome

- Hydromorphone is contraindicated in patients with:

- known allergies to the drug, sulfites, or other components of the formulation.

- known hypersensitivity to opioids.

- severe respiratory depression

- paralytic ileus

- acute or severe bronchial asthma (1).

Caution should be exercised in patients with:

- respiratory insufficiency

- head injuries

- increased intracranial pressure.

- liver or kidney impairment.

Considerations for Nurse Practitioners

As nurse practitioners, it is crucial to assess the patient's pain intensity and overall health status before initiating Hydromorphone. Start with the lowest effective dose and titrate carefully for optimal pain control. Regular monitoring for adverse effects, signs of opioid toxicity, and therapeutic response is essential. Educate patients about the potential side effects, proper dosing, and the importance of not exceeding prescribed doses. Additionally, nurse practitioners should be familiar with local regulations and guidelines regarding opioid prescribing and follow appropriate documentation and monitoring practices.

Additional Considerations

In terminal cancer patients, clinicians should not restrain opioid therapy even if signs of respiratory depression become apparent.

Hydromorphone requires careful administration in cases of concurrent psychiatric illness.

Specific Patient Considerations:

- Hepatic impairment and Renal Impairment: Initiate hydromorphone treatment at one-fourth to one-half of the standard starting dosage, depending on the degree of impairment.

- Pregnancy considerations: Hydromorphone can traverse the placental barrier and induce NOWS.

- Breastfeeding considerations: Nonopioid analgesic agents are preferable for breastfeeding women.

- Older patients: hydromorphone is categorized as a potentially inappropriate medication for older adults (1).

Tramadol

Mechanism of Action and Metabolism

Tramadol is a Schedule IV opioid medication with a higher potential for dependency and misuse than non-opioid medications. It binds to opioid receptors in the central nervous system, inhibiting the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin. It also has weak mu-opioid receptor agonist activity.

The liver metabolizes tramadol mediated by the cytochrome P450 pathways (particularly CYP2D6) and is mainly excreted through the kidneys.

Tramadol is used for moderate to severe pain.

Available Forms of Tramadol include:

- Immediate-release-typically used for acute pain management.

- Extended-release-used for chronic pain.

Dosing and Monitoring

Tramadol has an oral bioavailability of 68% after a single dose and 90–100% after multiple doses and reaches peak concentrations within 2 hours. Approximately 75% of an oral dose is absorbed, and the half-life of tramadol is 9 hours (18).

Tramadol dosing should be individualized based on the patient's pain severity and response.

The initial dose for adults is usually 50-100 mg orally every 4-6 hours for pain relief. The maximum daily dose is 400 mg for immediate-release formulations and 300 mg for extended-release formulations (18).

It is essential to monitor the patient's pain intensity, response to treatment, and any adverse effects. Regular reassessment and adjustment of the dosage may be necessary.

Side Effects and Contraindications

Tramadol is responsible for severe intoxications leading to consciousness disorder (30%), seizures (15%), agitation (10%), and respiratory depression (5%). The reactions to Tramadol suggest that the decision to prescribe should be carefully considered.

Common Side Effects of Tramadol Include:

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Dizziness

- Constipation

- Sedation

- Headache

- CNS depression

- Seizure

- Agitation

- Tachycardia

- Hypertension

- reduced appetite

- pruritus and rash

- gastric irritation

Serious side effects include:

- respiratory depression

- serotonin syndrome

- seizures

Contraindications

Tramadol is contraindicated in patients with:

- history of hypersensitivity to opioids

- acute intoxication with alcohol

- opioids, or other psychoactive substances

- Patients who have recently received monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

Additionally, the following can be observed in tramadol intoxication:

- miosis

- respiratory depression

- decreased level of consciousness

- hypertension

- tremor

- irritability

- increased deep tendon reflexes

Poisoning leads to:

- multiple organ failure

- coma

- cardiopulmonary arrest

- death

Considerations for Nurse Practitioners

Tramadol has been increasingly misused with intentional overdoses or intoxications. Suicide attempts were the most common cause of intoxication (52–80%), followed by abuse (18–31%), and unintentional intoxication (1–11%). Chronic tramadol or opioid abuse was reported in 20% of tramadol poisoning cases. Fatal tramadol intoxications are uncommon except when ingested concurrent with depressants, most commonly benzodiazepines and alcohol (18).

Tramadol poisoning can affect multiple organ systems:

- gastrointestinal

- central nervous system: seizure, CNS depression, low-grade coma, anxiety, and over time anoxic brain damage

- Cardiovascular system: palpitation, mild hypertension to life-threatening complications such as cardiopulmonary arrest

- respiratory system

- renal system: renal failure with higher doses of tramadol intoxication

- musculoskeletal system: rhabdomyolysis

- endocrine system: hypoglycemia, serotonin syndrome (18)

Cannabis

Mechanism of Action and Metabolism

Cannabis is classified as a Schedule I status. It contains various cannabinoids, with delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) being the most studied. THC primarily acts on cannabinoid receptors in the brain, producing psychoactive effects, while CBD has more diverse effects on the nervous system. These cannabinoids interact with the endocannabinoid system, modulating neurotransmitter release and influencing various physiological processes (32).

Similar to opioids, cannabinoids are synthesized and released in the body by synapses that act on the cannabinoid receptors present in presynaptic endings (32). They perform the following actions related to analgesia:

- Decrease the release of neurotransmitters.

- Activate descending inhibitory pain pathways.

- Reduce postsynaptic sensitivity and alleviate neural inflammation.

- Modulate CB1 receptors within central nociception processing areas and the spinal cord, resulting in analgesic effects.

- Attenuate inflammation by activating CB2 receptors (32).

- Emerging research shows cannabis is indicated for:

- Migraines

- chronic pain

- back pain

- arthritic pain

- pain associated with cancer and surgery.

- neuropathic pain

- diabetic neuropathic pain when administered early in the disease progression.

- sickle cell disease

- cancer

- inflammatory bowel disease (32)

Available Forms

Cannabis refers to products sourced from the Cannabis sativa plant. There are differences between cannabis, cannabinoids, and cannabidiol (CBD). Cannabinoids are extracted from the cannabis plants. Cannabinoid-based treatments, such as dronabinol and CBD, are typically approved medical interventions for specific indications. THC (9-tetrahydrocannabinol) is the psychoactive component of the cannabis plant. CBD is a non-psychoactive component (32).

Cannabis can be consumed in different forms, each with a different onset and duration. Patients may have individual preferences, including:

- smoking/vaporizing dried flowers.

- consuming edibles

- tinctures or oils

- applying topicals (32)

Dosing and Monitoring