Chest Tubes Nursing Care Troubleshooting: When to Call the Doctor

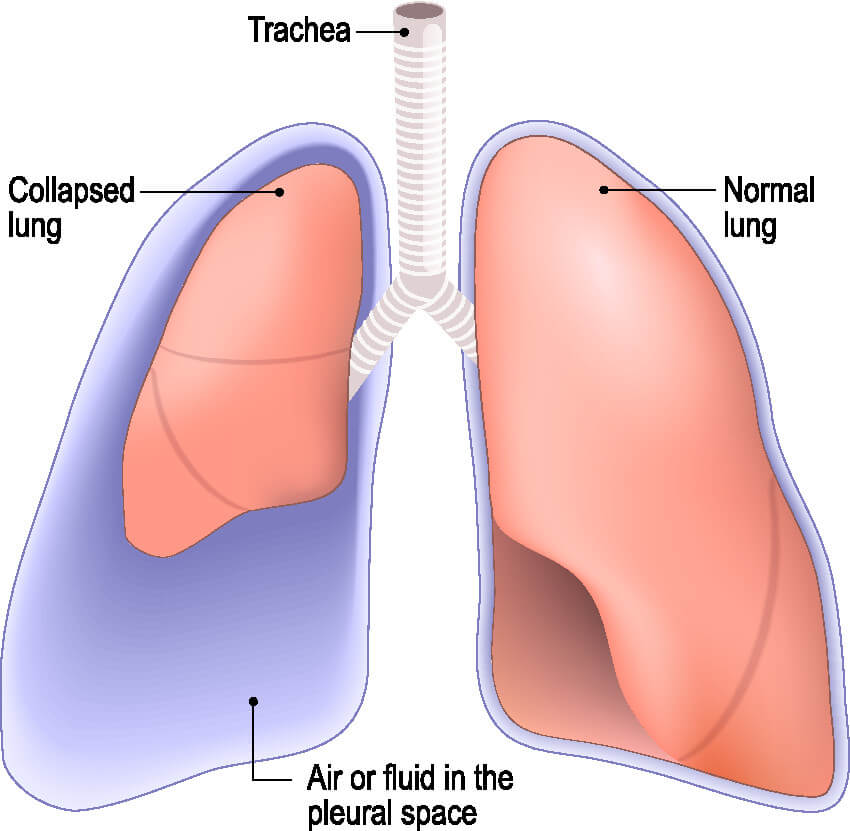

Like anything else, chest tubes are prone to complications. It is essential for nurses to be able to identify a malfunctioning tube quickly and know when to alert the provider. A worsening pneumothorax can lead to a longer hospital stay for the patient, or at worst tension pneumothorax and death.

Tube/Drain Malfunction

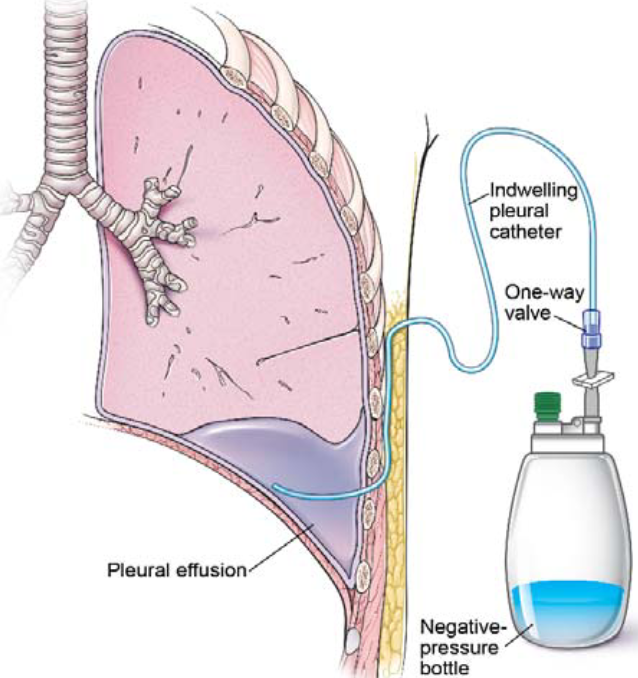

Chest tubes should be assessed regularly by nursing staff. The chest tube must be well-connected to the drainage system and wall suction (if necessary). If the chest tube becomes disconnected from the drainage system, the two ends should be cleaned well with an antiseptic, like alcohol pads, prior to being reconnected (1). You can also stick the open end of the chest tube into a bottle of sterile water or saline to quickly create a water seal (13). Do not clamp the tube in case there is an air leak, as the patient could develop a tension pneumothorax (1). If the tube is completely pulled out from the patients’ chest, immediately apply pressure and apply a sterile petroleum impregnated gauze over the site and call the physician immediately (13).

Infection

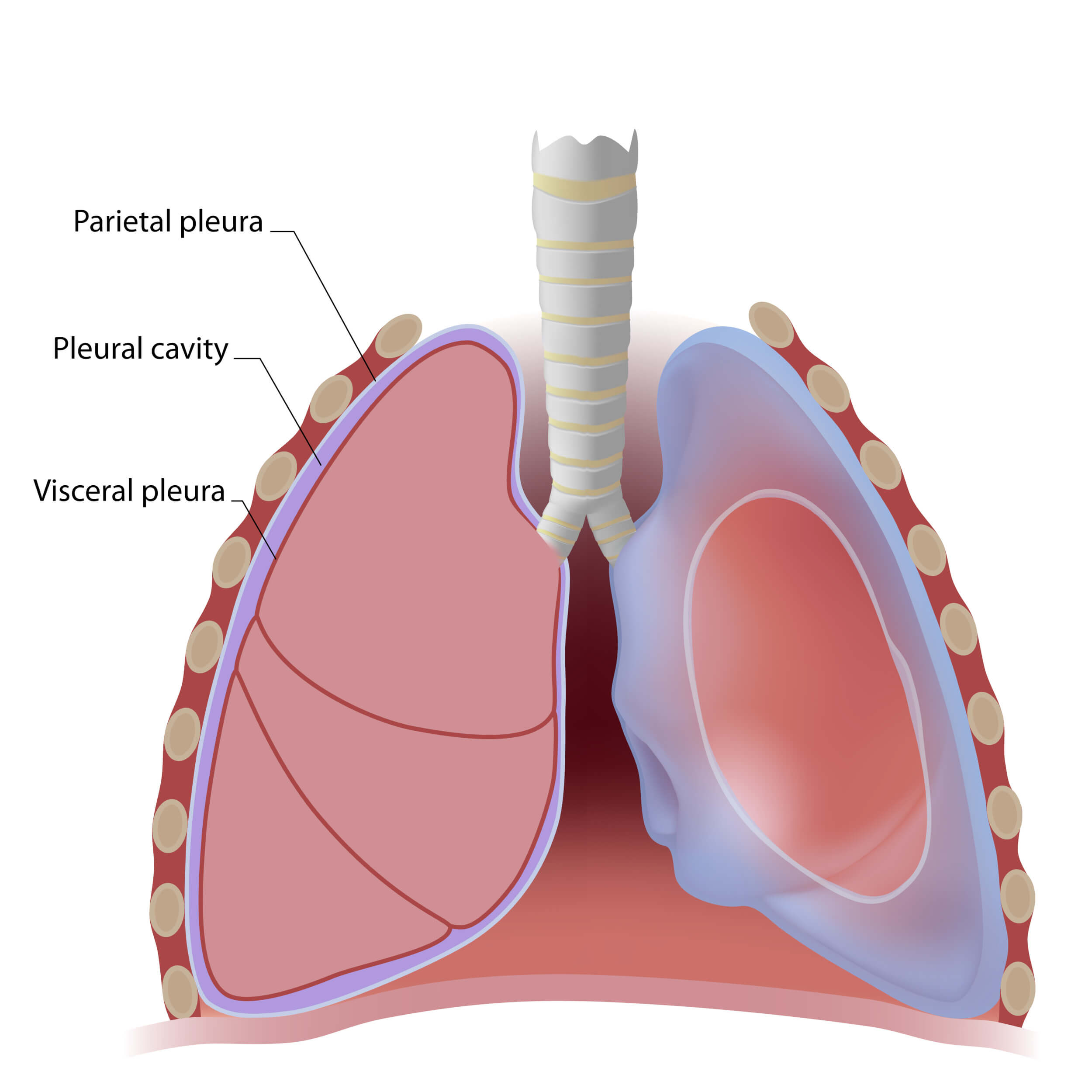

Infection is always a risk when a foreign body is present. Because chest tubes allow direct access into the chest cavity, it is essential to watch closely for any signs of infection. Infection may develop at the insertion site or inside the chest cavity (empyema/abscess).

Signs of infection at the insertion site include fever, redness, swelling, warmth, or purulent drainage. The site needs to be kept clean and soiled dressings should be replaced quickly and efficiently.

Chest tube patients that also have pleural effusions are at higher risk of developing empyema (1). Chest tubes are considered a “clean contaminated” procedure, meaning the chest cavity is accessed cleanly, but a risk for contamination remains as long as the tube is in place (1). The risk of empyema after chest tube insertion is as high as 25% in some populations. A nurse might suspect the development of empyema/abscess if the patient exhibits symptoms of infection: fever, tachycardia, respiratory distress and purulent drainage from the chest tube. A prompt call to the provider is warranted.

Kinks & Clots

The smaller the chest tube, the more likely it is to become clogged or kinked. Sometimes it is easy to spot a problem with a simple inspection of the entire apparatus. Pay particular attention to areas of the tubing covered with tape, such as the insertion site or taped connections. Straighten out the the tubing when patients are lying in bed or sitting in the chair.

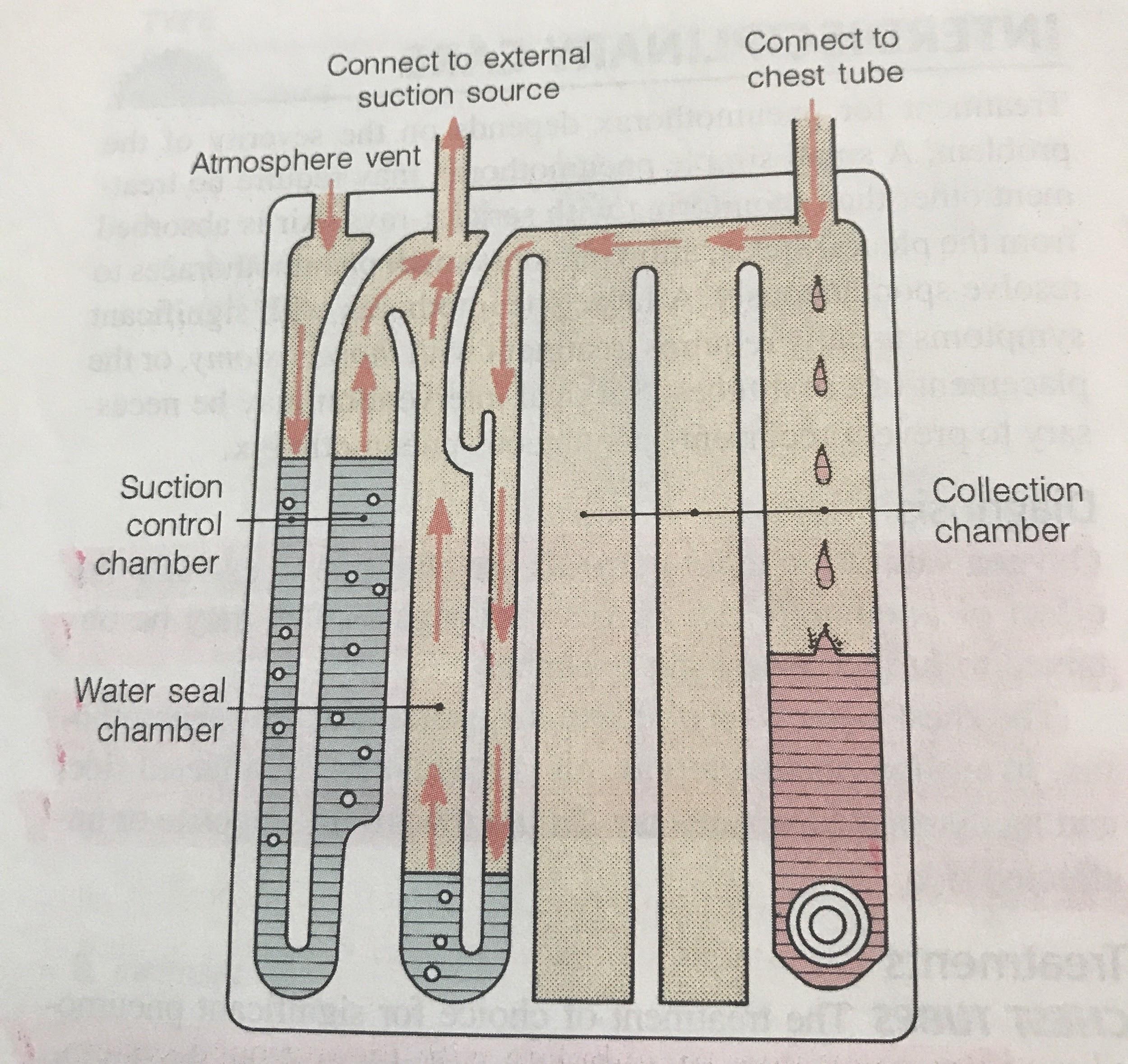

Pay close attention to the drainage system. A digital system or three-compartment syndrome will alert you if there is a problem. A digital system will literally sound the alarm in the event of a kink or clot because it monitors pressures. Three-compartment systems are not fitted with alarms, so they require closer observation to detect an issue. Earlier, it was mentioned that it is normal for the water seal in three-compartment systems to fluctuate with breathing or coughing. If the water seal is not fluctuating with breath, you may have a kink or clot. The water seal is not fluctuating because the tube cannot drain past the blockage.

Kinks are easy to fix: simply straighten out the tube or resolve kinked connections. Clots can be a little more difficult to handle. Luckily, ⅔ of clots resolve themselves (1). Historically, providers have used techniques such as milking or stripping the tube to help remove clots. The use of these procedures is questionable. Prophylactic milking/stripping has not shown any tendency to prevent clots from forming (1). Also, these techniques have actually been shown to cause harm by increasing pressure within the pleural cavity, resulting in increased bleeding, tissue entrapment, and dysfunction of the left ventricle (1). Thus, tube milking and stripping should probably be avoided altogether.

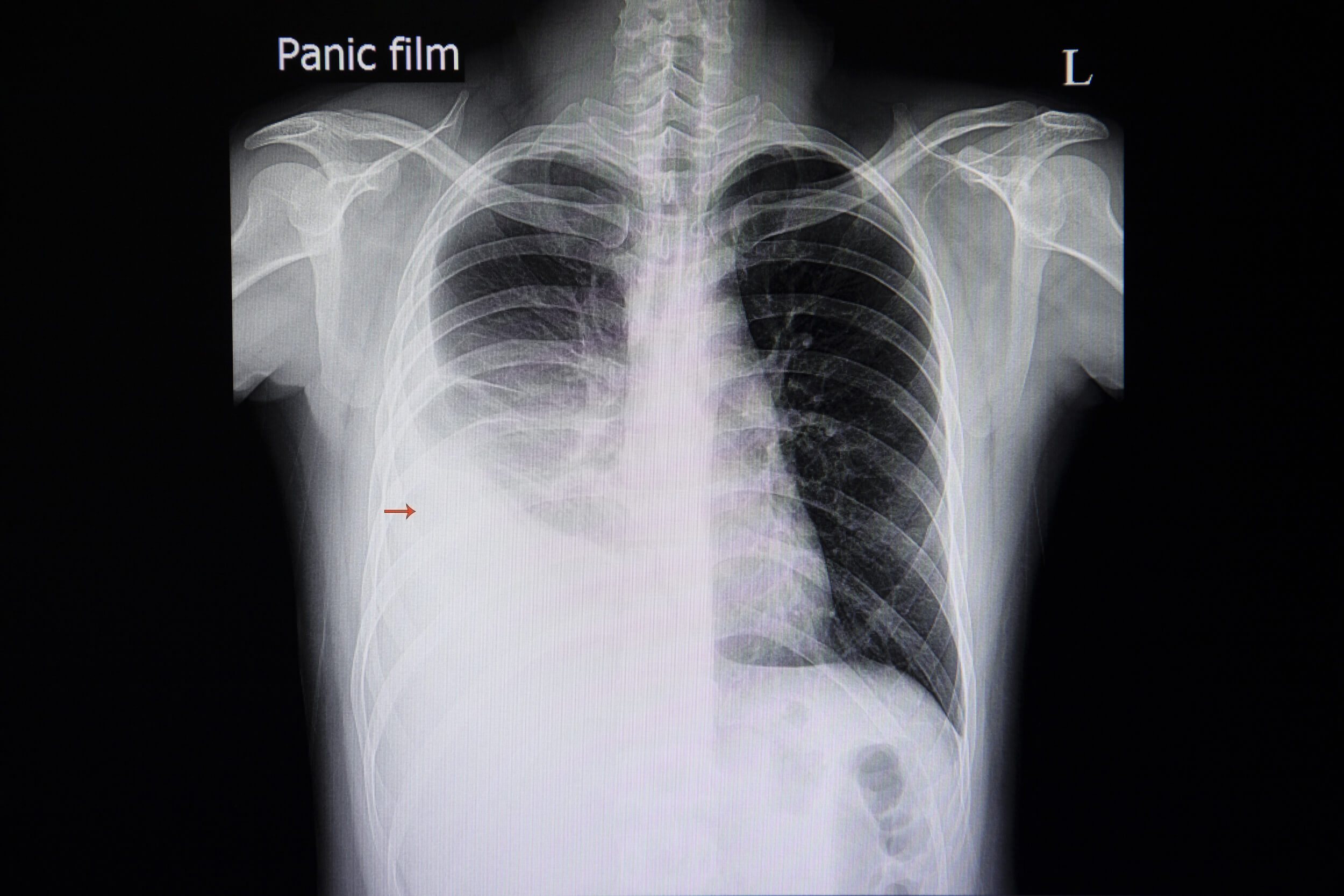

What do you do if you see a clot then? If the clot is located in the drain system tubing, simply replace the system. Attach a new Pleur-evac® or Atrium® system and remove the affected tubing. If that doesn’t resolve the problem, notify the provider. Chest tubes can also become kinked inside of the patient, so the provider may order a chest x-ray to confirm proper tube placement (2).

Loss of Suction

Loss of Suction. Ensure that the drain tubing is securely attached to the wall suction regulator and that the tubing is unclamped. The regulator should be turned on. Check that the suction dial on the drain system is set to the appropriate suction setting and that the suction is continuous, not intermittent. If all connections are appropriate, the wall regulator or drain system is malfunctioning and should be replaced. Maintaining appropriate suction is critical, as too little suction will prevent lung re-expansion, while too much suction can damage lung tissue (9).

Drain System Malfunction

The best course of action is to replace the drain system and re-assess the problem. If it was truly an issue with the drain system it should resolve by replacing it.

Air Leak

The easiest way to assess for an air leak is to observe the drainage system. Again, a digital system will alarm if it detects a problem. With a three-compartment system, an air leak will cause intermittent or constant bubbling within air-leak detection compartment of the water seal. Air leaks are a concern because they allow air to flow back into the pleural space (1). The whole point of the chest tube is to get the air out of the chest. Air leaks can occur in a couple places: at the insertion site or within the tubing/drain system (1).

If an air leak is observed in the water seal chamber, the next step is to find out where it is coming from. This is one case where clamping the tube (temporarily, of course) can help diagnose a problem. First, clamp the tube close to the patient (10). If bubbling within the water seal continues, this means there is a leak in the tubing or drain system. Although made of strong material, these drain systems are not infallible. Tubing can be cut or damaged accidentally, and it may not be easy to spot. Assess the tubing for cuts or holes. Ensure all connections are secure, as loose connections are an easy way for air to sneak inside. Replace the drain system if the tubing or container is damaged.

On the other hand, if you clamp the tube and the air leak disappears from the water seal, this means air is leaking near the patient (10). In this case, the leak stems from the insertion site or somewhere inside the chest (10). An air leak at the insertion site occurs because the dressing is insufficient or the hole is too big. This is why an occlusive dressing is a must. Apply new petroleum gauze and cover with a sterile, occlusive dressing at the site where the tube enters the skin (10). This prevents air from leaking into the chest at the skin.

Unfortunately, sometimes the skin site is too large relative to the tube itself, meaning the tube is too small for the skin incision that was created (1). The tube should fit snugly into the skin incision, without gaps. If you suspect the skin incision is too large, notify the physician. Often, a simple stitch can tighten any loose skin at the insertion site (1).

Finally, if you have accounted for all of the potential problems listed above and an air leak remains, the problem is likely inside the chest (10). Potential causes of persistent air leak include residual pneumothorax, pleural injury, a malpositioned chest tube, or fistula (10). Notify the provider right away if all attempts to resolve an air leak have failed.

Tube Dislodgement

Sometimes, the tube comes out despite every precaution. It may be pulled out partially or completely. After a partial removal of the tube, quickly and calmly secure the tube to the patient with a new dressing and tape. Obtain a set of vital signs and assess for pain and any new symptoms, such as shortness of breath or dyspnea. Notify the provider immediately. Follow up imaging (usually an x-ray) may be ordered to determine chest tube location and assess for any residual pneumothorax.

If the tube is pulled completely out, put on gloves and quickly cover the insertion site with your hand to prevent air from flowing into the chest (10). Stay with the patient and call for help. When help arrives, ask a coworker to get the necessary supplies for a new occlusive dressing: petroleum gauze, dry sterile gauze, and tape. Apply the dressing and notify the provider immediately. If the patient is in distress, call for help. Remember, chest tubes can be placed at the bedside pretty quickly in an emergency. And try to stay calm!

Under normal circumstances, chest tubes are removed once drainage has ceased, breath sounds return to normal, and/or imaging shows a resolution of the pneumothorax (9).

Licensed and retrieved from Adobe Stock

Licensed and retrieved from Adobe Stock