Course

A Nurses Guide: How to Deal with Difficult Patients

Course Highlights

- In this A Nurse’s Guide: How to Deal with Difficult Patients course, we will learn about a greater understanding of anger in themselves and others.

- You’ll also learn what happens in the brain when a person becomes angry.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of the skills necessary in providing care to patients when they become angry.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 2

Course By:

Lauren Stephanoff

RN, BSN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

Being in the business of caring for people when they are at their worst means we often come face-to-face with patients amid emotional outbursts of anger. We can improve patient outcomes and our work-life satisfaction by making attempts to understand anger, learning and becoming aware of what goes on in others’ brains when they are upset, and adopting optimal techniques for handling these tough situations. Learning how to deal with difficult patients and being able to resolve conflict in a positive manner is one of the most valuable skills a nurse can possess.

What is Anger?

Depending on your personal life, you will likely have your own opinion about anger as an emotion. By definition, anger is “antagonism toward someone or something you feel has deliberately done you wrong” (9). Generally, it does not feel good to experience anger in ourselves, nor is it pleasant to be around others who are feeling this way. Becoming angry is a part of being human, and as a healthcare professional, we must learn more about it so we are aware of how to deal with difficult patients. Perhaps approaching this from a philosophical standpoint will further help us to see beyond our patient’s immediate anger and we can work to develop a plan to resolve the conflict.

Anger as a Motivator

First off, anger can be motivating. Oftentimes, when we perceive that there is a problem that is causing harm or injustice – whether it is affecting ourselves, a patient, or the barista at the corner coffee shop – it is often anger that pushes us to act. As a very basic (and optimistic) example, a patient might be angry about being “stuck in the hospital.” Optimally, the experience will bother them enough to want to follow all of the steps their physician provides so that they do not have to be readmitted.

Anger and Catharsis

For some, the act of being angry can be cathartic. Catharsis can be described as a “purging” or “cleansing” of the emotions. For example, when we feel angry and begin to shout or slam a door, it is actually a way of releasing built up and negative energy. Some people achieve catharsis and release their anger in productive ways, such as exercising, talking with a friend or therapist, journaling, or cleaning. Once you have completed the action and released the anger that you had, you can slowly begin to calm down (1).

If we don’t release this energy over long periods of time, it can unfortunately cause physical harm. Anger can increase heart rate, blood pressure (think heart attack or stroke), blood sugar, and intraocular pressure. Anger can lower our immune function, increase incidents of cancer, affect the digestive system, decrease bone density, and can be the cause of headaches and migraines. Being angry can also negatively impact our short-term memory as well as the ability to make rational decisions (2). Applying therapeutic techniques can be a beneficial method of dealing with difficult patients, as this can provide the opportunity to release pent-up emotion before it leads to physical harm.

Anger and Control

When learning how to deal with difficult patients, we must consider the relationship anger has with control. When a person is in our care, there is undoubtedly at least one major thing going on with them that they cannot control (i.e., health problems). Being in a hospital setting can remove the controlled variables that the patient has been accustomed to from their daily life (i.e. foods, who they come in contact with and at what time, etc.) and a common response to this change is anger in an attempt to regain control of the situation (1). Additionally, patients may be fearful about their disease process, or angry about a lack of financial coverage for their care (1).

Stress and Trauma

There is a strong correlation between people who carry a lot of anger inside and stressful life events, particularly childhood trauma such as neglect and physical abuse. There’s also an association between anger and psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder. Further, studies show and association between Many people with these and other psychiatric disorders and childhood trauma likely have experienced extreme stress and trauma in their youth (3).

What’s Happening in the Brain?

The amygdalae are a couple of bunches of neurons found deep in each temporal lobe that play an important role in our emotions, including triggering the fight or flight response (5). The hypothalamus is near the base of the brain right under the thalamus, and is attached to the pituitary gland (6). Among many other things, the hypothalamus is responsible for controlling the secretion of hormones from the pituitary gland, which is located behind the nose (7). Finally, our adrenal glands sit on top of our kidneys and release different hormones, particularly, stress hormones (2).

The Hormone Cascade

Imagine this scenario. You’ve just sat down to chart. The call light goes off for what seems like the hundredth time. You haven’t eaten or used the restroom all day. In this scenario, the amygdalae, like canaries in a coal mine, sound the alarm by signaling the hypothalamus to release a corticotropin-releasing hormone — causing the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone. This chain of hormone release tells the adrenal glands to drop big stress bombs: adrenaline, noradrenaline, and cortisol (2).

When there’s too much cortisol, increased calcium is allowed to enter neurons, which can end up causing them to die. The prefrontal cortex (PFC) and hippocampus suffer the most from this outcome. The function of the PFC becomes suppressed, which affects the ability to have good judgment, for example, saying something hurtful to someone you care about during an argument. As a result, neurons die in the hippocampus (where memories are stored). So if the PFC is not working well, our short-term memory and ability to store new ones are affected most (2).

The presence of too much cortisol will also result in a lack of serotonin – the happiness neurotransmitter. With less serotonin, there will more sensitity to pain and anger, an increase in aggression, and a potential for depression (2).

Consider every time you have ever tried to reason with a person who was already upset. How did it go? Did they immediately come to see the error of their ways? I can think of several occasions where a patient was so enraged about something that fixing whatever the issue was did nothing to quell the tirade. When trying to figure out how to deal with difficult patients, understanding what is going on in their brain during these episodes of rage can help us to make sense of it all and how to plan a deliberate, appropriate, and effective way to resolve the conflict.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Have you ever experienced being so angry that you experienced an “amygdala hijack”?

- If so, would you have called yourself “reasonable” when you were in that state?

- Consider the last time you dealt with someone who was angry in light of the above cascade of events. Does it make more sense now (if you weren’t already aware of what happens)?

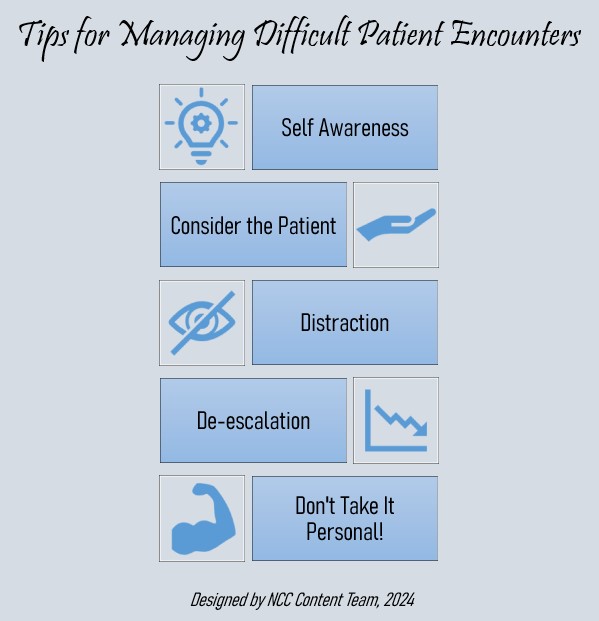

Tip 1: Self-Awareness

Self-awareness is extremely important when learning how to deal with difficult patients. Nurses who are aware of their own experiences, feelings, and triggers may be better prepared for how to respond to others in heated situations (1). For example, suppose a nurse grew up in a household where they frequently experienced violence. In this case, the nurse might respond in an unexpected, unhelpful, and unprofessional way when exposed to angry behavior from others, such as shouting back. On the flip side, perhaps the nurse grew up in a household where there was little to no conflict and they are unsure of how to properly respond when someone behaves angrily towards them. Maybe they have been judged harshly for their feelings and/or resulting actions, and consequently, judge others the same in turn.

Oftentimes we may not be aware of our own tendencies until we step back and intentionally evaluate them. Self-awareness involves considering personal experiences, thoughts, judgments, and triggers. This can lead to heightened awareness of the reasons for responding in various ways. Nurses who engage in self-awareness may be more prepared to respond in a deliberate way when they find themselves in a scenario with a disgruntled patient.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself to better understand your patient’s (and your own) reaction in difficult situations (1):

- How did the patient react to me during the encounter?

- Do other people in my life react to me in a similar way?

- Do I react the same way to other people in my life?

- What patterns do I notice are present in both my personal and professional life?

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Have you ever gotten so upset that you ended up making a bad decision?

- Has anger ever motivated you?

- What is your opinion of anger? How do you respond to others when they are angry?

- Think of at least three benefits of releasing anger.

Tip 2: Consider the Patient

“Calm down!” and, “It’s not okay to yell!” yelled the nurse. We’ve all heard the countless ways healthcare professionals respond when figuring out how to deal with difficult patients who are angry. Many nurses may find themselves yelling similar statements. Being yelled at can be very triggering. Rather than being hard on themselves, nurses should evaluate how to respond for the next time and prepare as best as possible because dealing with difficult patients is inevitable.

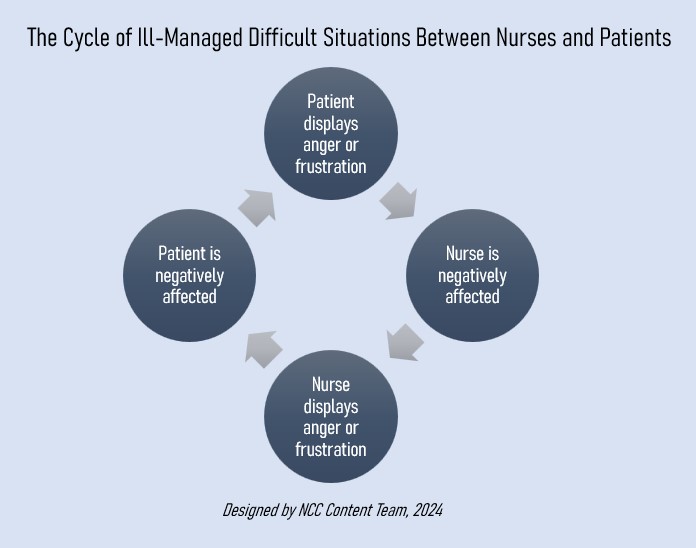

Often, clinicians may become triggered – in other words, they may get angry or irritated when confronted with an angry patient. If not mindful, they may subsequently give in to that trigger and inadvertently make what’s going on with the patient about themselves when the patient is the one who needs care. When learning how to deal with difficult patients, keep in mind that by responding with anger or with words that are seeking to control, the patient may miss an opportunity to release their pent-up, intense energy which can result in physical harm.

I am reminded of a time when my daughter was an infant. She always had a terrible time facing backward in her car seat. We were riding with a friend of mine and her six-year-old son when my daughter began to cry. The young boy covered his ears, saying, “Why does she have to be so loud?” My friend’s golden response was, “I know, honey, it’s no fun, but think how much worse it must be for her.”

Even though this scenario is quite different from a healthcare environment, it can be applied to caring for patients. Even though nurses may be frustrated by difficult patient encounters, thinking of how the patient may be feeling can help to keep the focus on the patient (and on providing the best possible care despite their behavior). Many patients have never faced health challenges that threaten their identity and/or morbidity, and therefore may struggle with ineffective coping (1).

Tip 3: Distraction

Another common approach to dealing with difficult patients during an angry episode is utilizing distraction techniques. Distraction and redirection to another activity may be helpful when managing situations with challenging patients (4). However, there are other instances where this technique may not be effective. Distraction may worsen agitation in some patients (4). Distraction can also come off as insulting to patients who are fully oriented which has the potential to exacerbate the issue.

An example of an appropriate time to utilize this technique is when dealing with a patient who has dementia and gets increasingly (and repeatedly) worked up over her belief that her loved one – who hasn’t seen the patient in recent history – is stealing from her. In this case, distraction might be the only way to keep her calm.

I work in a psychiatric setting, and when I was new to my position, I learned first-hand one technique that was not effective.

A 40-year-old, physically tall and sturdy male patient became so upset that he started punching our walls. Staff intervened and ending up having to assist him to the floor for everyone’s safety. Other than his increase in rate and depth of breathing, he was lying quietly, prone on the ground. I kept a safe distance and asked if he was alright: he didn’t respond. I wasn’t sure what to do or say. I was new, undoubtedly nervous, and hadn’t yet learned the value of what one of our psychiatrists refers to as “therapeutic silence.” I had learned in the past from my education and own personal experiences that breathing techniques were calming, so I tried saying, “it’s okay, just breathe.”

Subsequently, he began yelling at me. He was saying not to tell him what to do, that he hated me, and to go away. By suggesting something to him in that intense moment, he took offense. If I’m honest with myself, if I was upset and someone had said something similar to me, it might not have gone over much better.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Think of an interaction you’ve had with a patient who was angry.

- What was the outcome?

- Was it positive, or could it have gone better?

Tip 4: De-escalation

Beyond this lesson, you will find several publications that discuss in-depth how to manage de-escalation during potentially dangerous situations. De-escalation involves maintaining a calm demeanor and avoiding attempts to control the patient. As a result, the patient can feel respected, and the trust between the two of you builds. Every person and situation is different, so being able to assess a situation is critical to finding the best solution possible. De-escalation can sometimes be referred to as conflict management, crisis resolution, “talk down,” and defusing (8).

Safety First

Since we now know that during escalated, angry situations, our patient’s brains may not be functioning at full capacity, it may be helpful to “expect the unexpected.” Meaning, realize that one moment, a patient can seem calm, and the next they can be triggered.

With this in mind, the first thing we always have to consider is safety – for ourselves, the patient, and others nearby. Here are some recommendations for keeping everyone as safe as possible:

- Use clear and calm non-confrontational verbiage (8). Pay attention to your tone and attitude when speaking with patients who are difficult. Health professionals who are angry, defensive, fatigued, or distressed may inadvertently cause or exacerbate a challenging interaction (1).

- Be aware of what’s around you and your patient. Are there things that could be thrown or used as a weapon? Do you wear necklaces or long earrings that can be pulled?

- Use non-threatening body language when approaching patients (8). Always maintain a safe distance. If you don’t feel safe, get to safety. It’s okay to walk away from a situation if you feel that you are in danger, but never turn your back.

- Bring a co-worker if you need to go into the room of a patient who is angry – never go alone.

- Observe for signs of aggression. If your patient exhibits balled fists, getting too close to you, pacing, tense shoulders, glaring, tense jaw, facial flushing, shouting, or heavy breathing, be prepared. Use risk assessment tools for early detection of behavioral changes as needed (8).

- Try to keep the area clear of others who might be put in danger or exacerbate the situation. This might be a challenge when you’re focused on engaging with your patient. However, it is helpful if you and your coworkers are all on the same page. Consider working with management to train everyone to be on alert for potentially dangerous situations with patients and their loved ones.

What to Say or Not to Say

When I’m upset, the thing that helps me the most is feeling like I am being heard. For my patients, I have found that listening is one of the tactics that works best, but remember that in some instances, patients may have a hard time listening to others because they may become triggered. If that occurs, it can become difficult to maintain a calm demeanor that is necessary for de-escalating tense situations. Listening is a skill that not everyone excels in but it can make a huge difference when figuring out how to deal with difficult patients.

Tips to improve listening skills:

- Do not interrupt.

- Give your full attention rather than getting distracted by inner thoughts or environmental stimuli.

- Repeat back what you’ve heard to affirm you got it right.

- Ask related questions to show you’re concerned and want to deepen your understanding.

- Convey a sense of empathy by using your body language, and making brief statements like, “That’s understandable.”

Since there is not a specific prescription or solution for dealing with all patients who are angry, we need to stay tuned and be creative to reach a mutually beneficial goal. By staying calm and truly listening, we’re better able to understand what is going on so that we can attempt to remedy whatever the problem is when the time is right. After listening, affirming, and giving the patient time to calm down, we can begin to work toward a solution.

For example, a nurse might can say, “I hear that you’re upset about what happened, and that’s totally understandable. What can I do for you right now to help?” By approaching the situation this way, it affirms that the nurse heard the patient, respected their feelings, and genuinely wanted to help them. When learning how to deal with difficult patients, this is an extremely valuable tool to possess.

Additionally, body language is extremely important – it conveys so much! Simple adjustments like squaring ourselves to whomever we’re listening to and conveying accurate facial expressions depending on the situation ensures to the patient that we are giving them our full, undivided attention and that we truly care about what they are saying.

Boundaries

A word about maintaining boundaries; these are key! Just because a nurse aims to listen and convey kindness actively does not mean that the nurse is a pushover, and that patients under their care will get everything they want.

For example, as nurses, we all know that we often do not have the time (or energy) to have deep, confiding conversations with each and every patient. However, being kind can be done swiftly, and without caving to demands. A simple “no” can be said in a respectful manner. For example, we can briefly say in a kind tone, “I know it’s frustrating, and I get it, but unfortunately, I can’t talk with you right now because I’m in the middle of passing meds. Can we talk in half an hour or so?”.

There are also times when we have to set boundaries because we can see that we can’t handle what is happening at the moment. For example, a nurse is caring for a patient who is upset about their new ordered diet change and calls the nurse an offensive word. The nurse can set boundaries by saying “I want to listen to you, but I would prefer that you not refer to me in an offensive way.” If the patient continues to offend, the nurse can say “I understand that you’re upset and I would like to speak with you about your diet change, but I feel uncomfortable with your choice of words. Let’s talk later.”

We all have to figure out where our boundaries lie. If a nurse gets triggered by the angry behavior of others, they might do best excusing themselves early on to take a break and ask someone else to help with the situation. If triggered by difficult patients, it may be difficult for the nurse to respond properly.

Tip 5: Not Taking Things Personally

As nurses, I am sure we have all learned early on to not take anything personally, especially when dealing with difficult patients. In many cases, patient’s anger is not the nurse’s fault, and there are many factors outside of our control (1). We are not responsible for another’s feelings and reactions. As we mentioned previously, we are all probably guilty of saying something that we did not mean when we were upset and we wish we would have given it a second thought. However, there are other instances where the situation escalates to a point where the patient wants to speak with a manager, regardless of who is at fault. While it may helpful to recognize when a behavioral response is not in proportion with what actually happened, nurses should remember that challenging situations will happen, and we should simply do our best and refrain from beating ourselves up too much when our best seems to fall short.

We must take care of and be kind to ourselves. Our best is different every moment of every day, and that is all a part of being human. Some days, we might have a tough time and struggle with any number of things, just like our patients. Our temper might be shorter and our tone a little more on edge, but rather than judging ourselves too harshly, we should recognize our own humanity and just do our best.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you think of other ways of handling patients who are angry?

- What techniques have you employed?

- How effective have they been?

How to Handle When You Lose Your Cool

As we discussed earlier, when we become triggered, our prefrontal cortexes (PFCs) don’t work properly, and that is when our decision-making becomes poor. The good news is that, since we know what is going on in our brain, we can work on reactivating that precious (and potentially life-saving) PFC. At first, we might not be able to look at ourselves clearly until after an episode occurs, but we can learn to recognize the signs of becoming triggered by examining what happened. Once we can do that in real-time, we can intentionally work toward becoming calm again.

Be aware of the things we have reviewed here so you can effectively handle and devise a solution on how to deal with difficult patients who are angry. Bear in mind how challenging it can be not to have control, especially during situations where we are unable to make rational decisions.

Benefits of Effectively Dealing with Difficult Patients

As caregivers, we experience more job satisfaction when we can adequately learn to care for people who are angry. Imagine how rewarding it is to successfully manage situations and achieve positive outcomes for our patients that could’ve gone badly otherwise. Inappropriate reactions when caring for difficult patients can lead to disciplinary actions. Rapport increases when appropriately utilized techniques are applied in practice because it fosters trusting relationships with the patient (1).

For patients, these situations serve as great opportunities to release some of their anger. If we can be facilitators, assisting them to come to a more even-keeled place, they will likely experience better outcomes. Additionally, a situation involving an angry patient can become dangerous quickly, so it is critical that we learn these skills for our own safety, and that of our patients.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you think of other benefits?

- Can you think of a time when you experienced first-hand or observed a situation involving a patient who was angry become worse because of how it was handled?

- Has a patient who was angry ever apologized to you for their behavior?

Case Studies

Case Study #1

A 46-year-old female patient received an intramuscular (IM) injection in her right gluteal area this morning. It is afternoon shift change, and she is complaining that her right hip has been hurting since receiving this injection. She has repeatedly been approaching the nurse’s station about this issue. The off-going day shift nurse yells over his shoulder as he’s frantically attempting to finish documenting, “I’ve already assessed you, and I don’t see anything wrong. I talked to the doctor, and he ordered Ibuprofen which you received. I have let her know that you would like to speak with her. You’ll have to wait until she rounds next.”

The patient begins yelling, stating, “None of you care about me! My doctor doesn’t care about me! Otherwise, she wouldn’t make me get these injections that hurt me!” The evening shift nurse arrives, sees that the patient she knew from the evening before is upset and that the off-going nurse is busy. The evening nurse steps behind the station desk so that there’s a barrier between her and the patient (in case she becomes more agitated and aggressive) and turns to face the patient with a concerned expression in place. She tells the patient “I see that you’re upset. How can I help?” The nurse listens, not interrupting the patient as she relays her issue.

At a natural lull in the patient’s speech, the nurse responds, “It sounds like you’re frustrated about this situation. I get it. That’s totally understandable.” The patient goes on to express her feelings of not being cared for by the staff or the doctor, tearfully raising her voice. The nurse looks at the patient with concern and considers the possibility that this woman might have some history of not being cared for. She continues to listen as the patient goes on venting. Eventually, the patient shouts one last time, turns away, and stomps down the hall to her room. An hour later, she returns looking tired, a little embarrassed, but calm, and apologizes then thanks the nurse for listening.

Case Study #2

A 70-year-old male patient rings the call bell. The nurse answers and the patient shouts loud enough to be heard without the aid of the speaker, “Get over here! You people are useless! Because of you, I’m swimming in a puddle of my own urine.” The nurse responds, “Okay, but you don’t have to be so rude.” She slams the phone down, muttering expletives to herself. She takes her time, finishing up what she was working on, still ruminating over the patient, while he gets increasingly upset.

She walks into the patient’s room, and she sees that he’s standing next to his bed, naked, leaning precariously on his IV pole. She says, “What are you doing? You’re going to fall.” The patient responds, “Well, you’re not doing your job!”

“I shouldn’t have to deal with this,” the nurse mutters under her breath as she begins to gather the soiled sheets. The nurse, whose back is turned to the patient, doesn’t see that his face has turned red, his eyes are bulging, and his knuckles are white as he grips the IV pole. The patient attempts to use the pole as a weapon to hurt the nurse but ends up slipping on his urine-wet feet, striking his head against the wall, resulting in a concussion. He files an official complaint regarding the nurse and considers suing her for damages. The nurse gets disciplined.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Think of one example from your practice that you have experienced or observed that went well and another that did not.

- What were the key elements that you think made the difference?

Conclusion

People get angry – it’s just a fact of our existence. Some, unfortunately, misbehave when they feel anger whether it’s out of frustration, stress, feelings of loss of control, or unmanaged old triggers coming to the surface. As nurses, we often have to figure out how to deal with difficult patients while at the same time being able to remain calm and composed. By understanding more about people who experience excessive anger and learning to apply the techniques discussed in this course, you should be able to form flexible and creative solutions that can result in making the best out of very challenging situations.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What kind of work training have you received on safety?

- Think about three things that help calm you if/when you get upset.

- Think of when you are listening to a patient. What do you do to show that you are actively listening?

- What are some phrases you would feel comfortable saying that would show that you care and are actively engaged? (For example, “That sounds frustrating.”)

References + Disclaimer

- Breiten, K., Condie, E., Vaillancourt, S., et al. (2018). Successfully managing challenging patient encounters. My American Nurse: Official Journal of the American Nurses Association. https://www.myamericannurse.com/challenging-patient-encounters/

- National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Medication. (2020). How anger affects the brain and body [infographic]. https://www.nicabm.com/how-anger-affects-the-brain-and-body-infographic/

- Di Benedetto, M. G., Scassellati, C., Cattane, N. (2022). Neurotrophic factors, childhood trauma and psychiatric disorders: A systematic review of genetic, biochemical, cognitive and imaging studies to identify potential biomarkers [Abstract]. Journal of Affective Disorders, 308, 76-88. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0165032722003184

- Mulkey, M. A., & Munro, C. L. (2021). Calming the Agitated Patient: Providing Strategies to Support Clinicians. Medsurg nursing : official journal of the Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses, 30(1), 9–13.

- Moyer, N. (2019). Amygdala hijack: What it is, why it happens and how to make it stop. Retrieved February 18, 2021, from https://www.healthline.com/health/stress/amygdala-hijack#overview

- Seladi-Schulman, J. (2018). Hypothalamus: Anatomy, function, diagram, conditions, health tips. Retrieved February 18, 2021, from https://www.healthline.com/human-body-maps/hypothalamus

- Seladi-Schulman, J. (2018). Pituitary gland overview. Retrieved February 18, 2021, from https://www.healthline.com/health/human-body-maps/pituitary-gland

- Division of Health Care Improvement, The Joint Commission. (2019). Des-escalation in health care. Quick Safety, 47. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/workplace-violence/qs_deescalation_1_28_18_final.pdf?db=web&hash=DD556FD4E3E4FA13B64E9A4BF4B5458A

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Anger. https://www.apa.org/topics/anger/

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate