Course

Chest Tubes Nursing Care

Course Highlights

- In this course you will learn about the relative anatomy of chest tube placement in chest tubes nursing care.

- You’ll also learn the basics of procedure and chest tube types.

- You’ll leave this chest tubes nursing care course with a broader understanding of how to troubleshoot problems.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 4

Course By:

Charmaine Robinson

MSN-Ed, RN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Chest tube nursing care and placement is common procedure in many hospitals, yet nurses consistently rank them as one of the most overwhelming drains to care for.

A malfunction in a chest tube can be deadly for a client in a matter of seconds. Many hospitals have recognized them as a common source of error and client harm. For these reasons it is imperative that nurses understand how chest tubes function and how to care for them. In this course we will discuss the anatomy, indications, and care of chest tubes.

Introduction

The ancient Greeks were the first to record techniques used to drain the pleural space [13]. Though the process and equipment have evolved over the centuries, the basic principles have not changed [13]. Today, thoracostomy tube (more commonly known as a chest tube) placement continues to be a very common procedure.

Chest tubes are utilized for a variety of reasons, ranging from emergent placement to routine use after an elective surgery [13]. They can be placed just about anywhere – the bedside, the operating room (OR), and interventional radiology.

Most nurses will encounter chest tubes at some point during their career – perhaps frequently, depending on where you work. Thus, it is essential for nursing staff to feel comfortable with chest tube management. Unfortunately, like anything else in healthcare, chest tubes are at risk for complication. Quick identification of potential complications could be the difference between life and death. This course aims to expand your knowledge and increase confidence in chest tube management.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What do you think are nurses’ biggest challenges/fears with chest tubes?

- Can you think of any alternatives to removing fluid from the pleural space?

- What complications have you witnessed result from chest tubes?

- What do you anticipate is the most common client concern about chest tubes?

- In what areas of the hospital might you anticipate encountering a client on a chest tube?

What Is a Chest Tube?

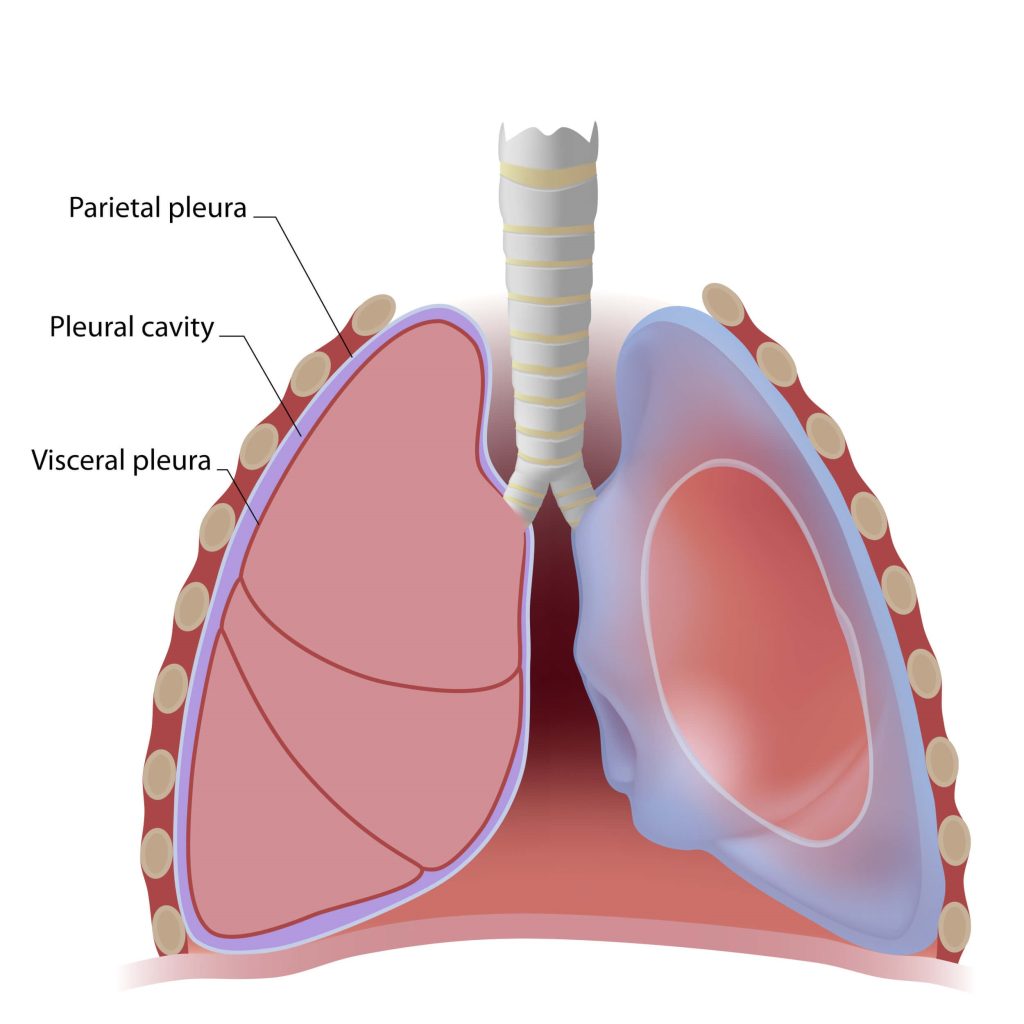

Let’s start with a quick refresher on the structure of our lungs. First comes skin (obviously). Beneath that is a layer of subcutaneous tissue, followed by muscle. Then we come to the ribs, which form the basic protective cage that holds our lungs, heart, and some very important blood vessels. Between each rib from top to bottom is a vein, artery, nerve, and more muscle [8]. Behind the ribs lies the first layer of the pleural space, called the parietal pleura [8].

This membrane lines the entire chest cavity. Then comes the pleural space, which measures about 15-20 microns wide in its normal state [8]. On the other side of the pleural space lies the visceral pleura, which is a membrane that covers the lungs, and then finally the lungs themselves [8].

What this means is that in a normal person, a small potential space exists between the lungs and the chest cavity, called the pleural space. When the pleural space becomes compromised and fills with extra fluid or air, the precarious negative pressure balance that keeps the lungs inflated is disrupted, forcing lung tissue to collapse.

Figure 1. Anatomy of the Lungs

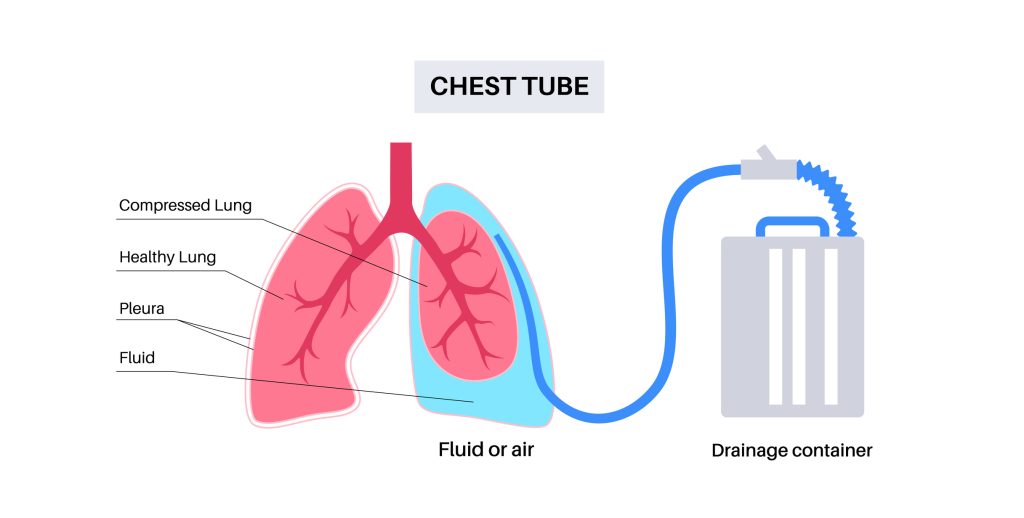

A chest tube comes to the rescue. Known officially as a thoracostomy tube, the chest tube is a hollow plastic tube that is carefully placed by a licensed provider. The tube is driven through the outer skin and muscle, between two ribs and past the parietal pleura to rest inside the pleural space [20].

Its purpose is to drain the excess fluid or air out of the pleural space so the affected lung can reinflate [20]. The tube is attached to a drainage system to facilitate the movement of the abnormal fluid/air out of the pleural space. The tube remains in place until the fluid/air is removed, the lung is reinflated, or becomes nonfunctional [5].

Chest tubes are generally divided into three categories based on size and method of insertion: large bore, small bore, and tunneled.

Large Bore (Blunt Dissection Technique)

Generally greater than 20Fr in size, large bore chest tubes are placed using the blunt dissection technique [5]. A quick aside here: the size ‘Fr’ refers to ‘French’ or the actual French word ‘Charrière’, which is the name of the Frenchman who invented the sizing [5]. The sizing is based on the diameter of a tube, with 1Fr = ⅓ mm (for example, a 12Fr tube is 4mm, 12÷3=4).

The blunt dissection technique requires a skin incision large enough to fit a finger [5]. A clamp or forceps is used to bluntly dissect intercostal tissues. The tube is inserted and held in place with heavy suturing [5]. This technique is more invasive. It also comes with some risks, including damage to surrounding structures, tube misplacement, bleeding, and increased pain [20].

Small Bore (Seldinger Technique)

Small bore chest tubes are generally less than 14Fr in size. They are placed using the Seldinger technique, which involves using an introducer needle to get access into the pleural space [5]. A guidewire is threaded through the needle and the needle is removed. Then the chest tube is threaded over the wire and the wire is pulled out, leaving only the chest tube. The tube is held in place with a suture and/or adhesive dressing. Advantages include a smaller incision, less pain, and it’s less invasive [5]. Conversely, they are more prone to blockage because they are smaller [5].

The decision to use a small or large bore chest tube is made by the provider. For the treatment of most pneumothoraxes, research shows that small bore chest tubes are as effective as larger tubes and may be less painful [7][10][12]. Large bore tubes are recommended to treat traumatic pneumothorax due to the need for removal of blood and air [12]. In the past, providers used large bore chest tubes to drain thick fluid like blood and pus, but more recent research suggests that small bore chest tubes are also effective if they remain patent and are properly inserted (catheter placed in the most dependent position for drainage) and maintained (frequently flushed with saline) [7].

Figure 2. Chest Tube Insertion Procedure

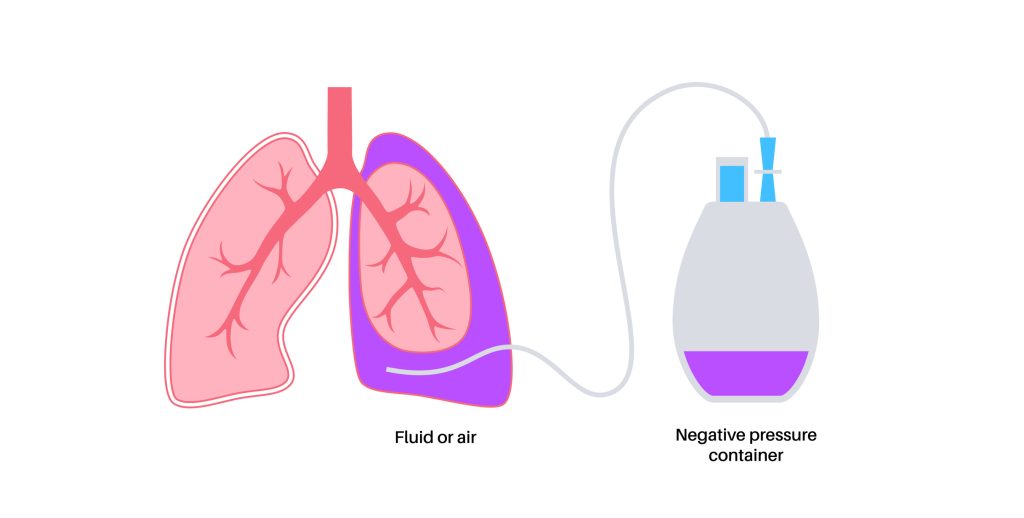

Tunneled (Indwelling)

Indwelling chest tubes (pleural catheters) are indicated for long term chest drainage, primarily as a treatment for malignant pleural effusion [5]. These tubes consist of a special catheter equipped with a cuff that remains under the skin and acts as an infection barrier [5]. The Seldinger technique is used to get access into the pleural space, along with a “peel-away” dilator that allows the tube to be tunneled under the skin. Two small incisions are required for placement. A special vacuum bottle is attached periodically to collect the drainage [5].

Figure 3. Pleural catheter

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Think about the anatomy of the lung, including the pleural space. Where exactly in this space are chest tubes placed?

- Is the potential space between the visceral and parietal pleura large enough for chest tube placement in the absence of pathologic conditions (pleural effusions, pneumothorax, etc.)?

- What is the disadvantage of using a small-bore chest tube versus a larger one?

- In what situation is a large bore chest tube prioritized over a small-bore chest tube?

- What you think is the primary difference in managing a chest tube versus an indwelling pleural catheter?

Current Practice

Bedside chest tube placement has become increasingly routine. Thus, bedside nursing staff may be directly involved with the initial chest tube placement [15].

The nurse may be asked to gather the necessary supplies for placement, ensure client consent is obtained, and assist with client education regarding the procedure [15]. The nurse may assist the provider during the procedure by participating in a pre-procedure ‘time-out’ and monitoring the client’s airway, vital signs, comfort, and response to the procedure [15]. Afterward, the provider will order a chest x-ray to verify placement and to confirm the absence of complications from the chest tube insertion. As always, the nursing staff is responsible for ensuring any post-procedure orders are carried out.

Once the chest tube is in place, verified by x-ray, and attached to a drainage device, nurses are tasked with monitoring the client and the drainage device. This would include monitoring vital signs as directed, observing for pain and signs of infection, and assessing the tube and drain system [15]. An important part of monitoring includes recording the amount and color of chest drainage. How often this is performed depends on nursing judgement, facility policy, and the provider’s written orders.

Perhaps the most intimidating aspect of chest tube management is ensuring proper function. It is the nurse’s job to look for signs that there may be a problem. Rest assured, these signs and symptoms will be discussed in detail later in the course.

There will also be orders for the nurse to change any dressings and provide necessary wound care. This includes routine observation of the chest tube insertion site. Depending on how long the chest tube is in place, nurses may also have to change out the drainage system if it becomes full of fluid.

Clients with chest tubes may ambulate, if appropriate, and travel to other departments within the hospital for other procedures. Chest tubes nursing care staff (most nurses) are responsible for ensuring the chest tube is properly packed up and stowed away for every adventure. This includes removing the chest tube from suction if suction is ordered and leaving the drainage system lower than the client’s chest. Remember, it’s okay, the water seal will keep anything from entering the client during transport and/or the procedure.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Why is it pivotal that imaging be obtained after every chest tube placement?

- What is one nursing role during the chest tube insertion procedure?

- How often do you monitor and document chest tube drainage/output in your facility?

- What concerns might you anticipate when transporting a client with a chest tube?

- Aside from monitoring the insertion site, what other parts of the chest tube system need close monitoring?

Indications for Chest Tube Placement

A chest tube may be indicated for the following reasons: pneumothorax/hemothorax, pleural effusion, empyema, chylothorax, and post-operatively after cardiac/thoracic surgery [13].

Pneumothorax/Hemothorax

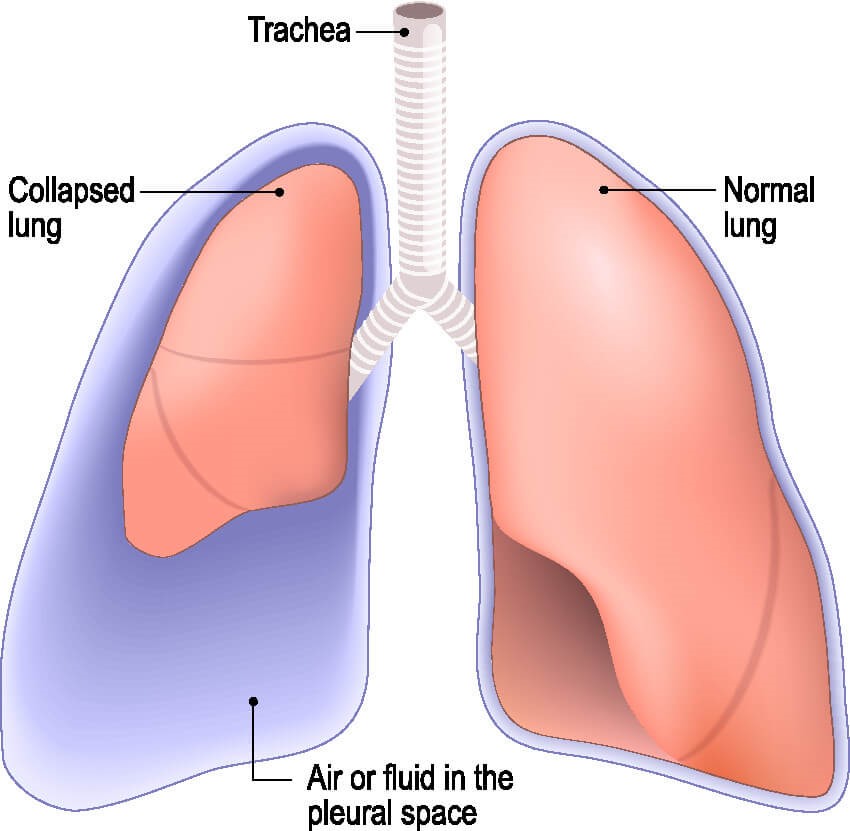

A pneumothorax, also known as a “lung collapse”, occurs when the normal negative pressure gradient within the lungs is compromised [3]. Air is introduced into the pleural space where it is not welcome. A pathway to the pleural space may form on the inside of the body when lung tissue is damaged. The connection typically forms at the airway or alveoli (the little air sacs in the lungs that encourage gas exchange) [3].

For example, a client with COPD or chronic bronchitis may develop enlarged, weakened alveoli called blebs that are prone to rupture. When this happens, air flows into the pleural space because of the difference in pressure, forcing the lung tissue to shrink or collapse in response to the expanding pleural space [3]. A pneumothorax can also be secondary to other medical conditions, such as asthma, cystic fibrosis, pneumonia, tuberculosis, cancer, and foreign body aspiration [4].

A pneumothorax may also occur from an outside source if an abnormal connection forms between the pleural space and the chest wall [3]. For example, during a lung biopsy, a needle is introduced into the lungs from the outside. Sometimes a pathway forms, allowing air from the environment to flow into the chest. In an attempt to equalize the pressure, air rushes into the pleural space.

A pneumothorax may also be spontaneous in a condition known as primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP) [3]. PSP usually occurs in tall, thin young men between the ages of 10-30 [3]. The risk is significantly increased with current or past smoking [3].

Finally, a hemothorax is diagnosed when blood becomes trapped within the pleural space. It often occurs with pneumothorax. Hemothorax may result from trauma, abnormal coagulation, spontaneously, or after certain medical treatments (such as a biopsy) [18][25].

Symptoms of pneumothorax and hemothorax include acute chest pain and shortness of breath (dyspnea). The pain may be worse during inhalation and localized to the affected side [3]. The degree of dyspnea is often proportional to the size of pneumothorax (bigger pneumothorax = more pain), but not always – a small percentage of people are asymptomatic [3].

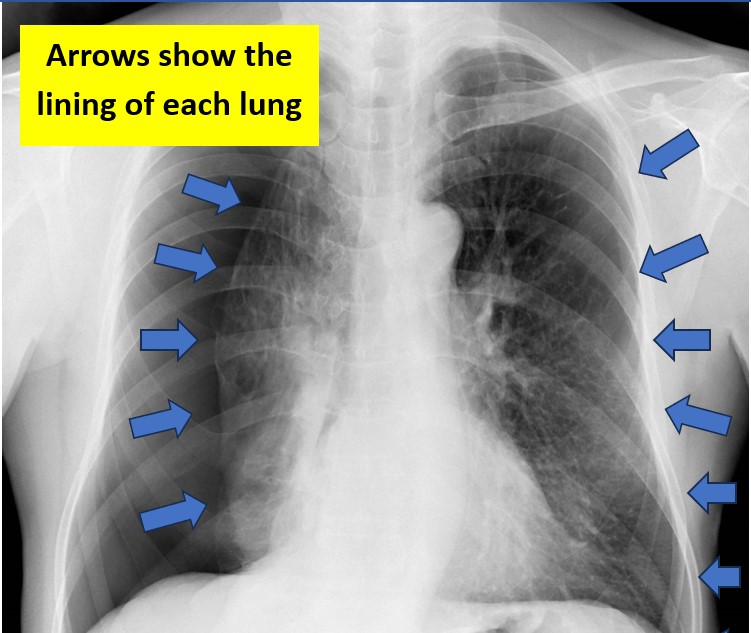

Figure 4. Air or fluid in the pleural space

Pleural Effusion

In a healthy person, the pleural space contains a small amount of serous fluid (about 0.1 to 0.3 mL/kg) that is secreted by the parietal pleura and reabsorbed by the lymphatic system [10]. When this carefully balanced system is disrupted, extra fluid can accumulate, known as a pleural effusion.

Pleural effusion is the result of leaky pulmonary capillaries. The capillaries leak for two reasons: changes in pressure or damage to the vessels themselves [10]. Congestive heart failure and renal failure are two causes of pressure changes. Capillary damage is caused by pneumonia and other infections, inflammation, cancer, and GI disease [10].

Pleural effusion in the pediatric population usually stems from infection, congestive heart failure, and cancer [1].

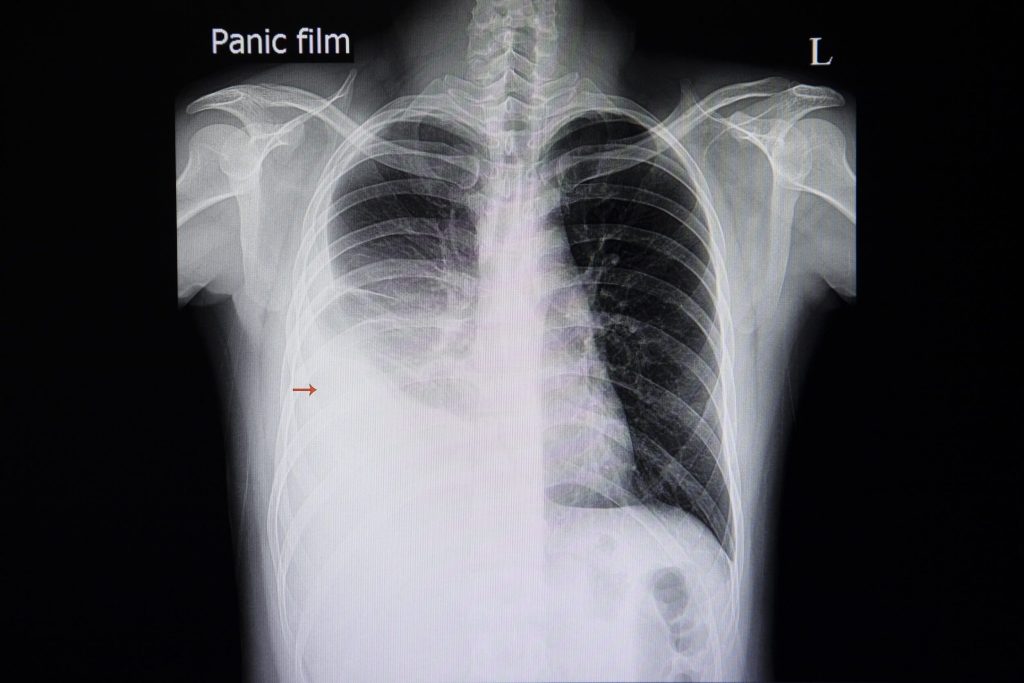

Image 1. Large right-sided pleural effusion

Empyema

Empyema is the development of infected, purulent fluid inside the pleural space [6]. Pneumonia is the usual suspect, but empyema can also form from a lung abscess, bronchopleural fistula (an abnormal tract/pathway between the bronchus and the pleural space), esophageal perforation, or complications of trauma and surgery [6].

The development of empyema begins with an inflammatory process in which fluid builds up in the pleural cavity (exudate stage), then pathogens colonize the fluid and causes [6]. When an infectious agent is introduced, inflammation brings white blood cells and even more fluid. Eventually, the infected material can grow into the pleural walls and cause tissue thickening, prohibiting lung expansion [6].

Purulent drainage associated with empyema can be thick and therefore difficult to drain. Fibrinolytics (medicines that dissolve blood clots) can be directly administered through the chest tube into the pocket of infection to help break it down and improve drainage [8]. tPA is the medication of choice. A small amount of tPA is diluted in saline and infused through the chest tube, which is clamped for a while (1-2 hours) before drainage is resumed [8]. The dose may be repeated if necessary.

Symptoms for pleural effusion and empyema include dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, cough, fever & chills if infection is present, and weight loss. Because a large volume of fluid can collect in the pleural space, cardiac failure is a differential diagnosis [6].

Post-Operative

Chest tubes are often placed after heart or lung surgery because of the risk for developing pleural effusion or pneumothorax during recovery. They are inserted while the client is still sedated prior to leaving the operating room.

Chest tubes are routinely placed following open-heart surgery, including cardiac bypass and valve replacements. They are also indicated in major thoracic surgeries, such as pneumonectomy, lobectomy, lung transplants, segmentectomy, and wedge resection.

Clients with chest trauma may require a chest tube in the presence of pneumothorax or hemothorax.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Think about the different conditions that can necessitate chest tube placement. What is the difference between a pneumothorax, hemothorax, pleural effusion, and empyema?

- What are the causes for each?

- Why are chest tubes often placed after heart or lung surgery?

- What is the role of fibrinolytics in chest tube management?

- Your client with a pneumothorax suddenly develops worsening dyspnea, what could be happening?

Client Considerations

When considering chest tube placement, it is important to evaluate the client. Because the indications for chest tubes range from routine post-op care to life threatening emergency, the presentation of these clients varies significantly. In all cases, client or family consent is paramount and should be obtained prior to the procedure.

The only exception to this is a true emergency, the process for which is outlined in your facility’s policies (all the more reason to be familiar with policy!).

Contraindications in chest tube placement should be considered as part of a risk/benefit analysis. For example, there are no contraindications for using chest tubes in the treatment of tension pneumothorax [13].

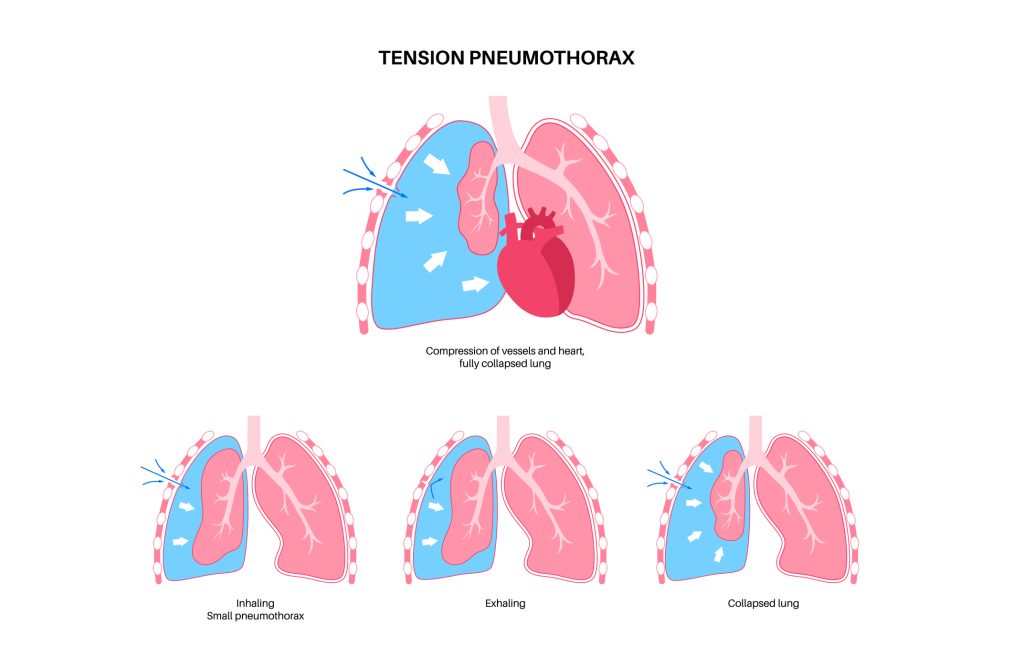

Tension pneumothorax is a medical emergency. It occurs when a pneumothorax or hemothorax becomes so severe that air can no longer escape from the pleural space. The pressure increases within the chest and forces the mediastinum (heart, great vessels, etc.) to shift out of the way, compressing the remaining unaffected lung [22].

Figure 5. Tension Pneumothorax

These clients are at high risk of going into shock or cardiac arrest. Signs and symptoms of tension pneumothorax include decreased breath sounds, hypotension, tachycardia, hypoxia, and tracheal deviation to the contralateral side of tension pneumothorax [14]. A tension pneumothorax can be diagnosed from a bedside ultrasound or chest x-ray.

Relative contraindications to chest tube placement include abnormal coagulation or infection at the insertion site [8]. Abnormal coagulation puts the client at higher risk of bleeding. The parameters for placement will vary between facilities, but generally speaking, prospective clients should have an INR < 1.5 and platelets > 50,000 [8].

Infection at or near the insertion site increases the risk of infection in the chest cavity [5]. In many cases, an alternate insertion site is available and should be utilized. For clients seeking elective or semi-elective chest tube placement, these relative contraindications should be resolved prior to placement, if possible.

A chest tube is considered elective if the client is stable. The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guidelines state that a client is clinically stable with a respiratory rate less than 24 breaths/min, pulse rate 60-120 beats/min, normal blood pressure, and oxygen saturation greater than 90% on room air [3].

The ACCP recommends that all clients with a large pneumothorax (greater than 3 cm apical length) get a chest tube [3]. Ultimately, the ordering provider will decide if a client requires a chest tube as an elective procedure or an emergency.

Potential Complications

When preparing a client for chest tube placement, it is important to be aware of potential complications. Chest tubes can be lifesavers but they are not without risk. When placed at the bedside or during an emergency, it is essentially a blind procedure.

Injury to Surrounding Structures

Gastrointestinal tract

Although rare, it is possible to for chest tubes to be placed beneath the diaphragm into the abdominal cavity. Insertion into the abdominal cavity poses risk for injury of the stomach, bowel, liver, spleen and other abdominal structures [13].

Though the overall risk is <1%, a third of all chest tubes that find their way into the abdomen result in injury to the client [13]. Signs of abdominal placement include the presence of stomach contents within the tube or peritonitis [13]. An x-ray would confirm that the chest tube is located below the diaphragm. Inserting the chest tube no lower than the 5th intercostal space helps prevent this problem [13].

Diaphragm

Many chest tubes are placed at the bedside without imaging guidance. Improper placement poses a risk for injury to the diaphragm [13]. Laceration, perforation, and muscle injury are the most common injuries [13]. Certain conditions increase the risk of diaphragmatic injury, including diaphragm paralysis, late pregnancy, obesity, ascites, and abdominal tumors [13].

Lungs

The lungs are at highest risk of injury during chest tube placement, especially if a client suffers from decreased lung compliance or pleural adhesions [13]. Lung injury is commonly missed because it cannot be visualized on imaging and clients may be asymptomatic [13].

A rare complication of chest tube placement is infarction of the lung. Excessive suction causes aspiration of lung tissue into the chest tube, leading to infarction and tissue death [13]. Providers must also beware of lung perforation and accidentally puncturing the pulmonary artery (as evidenced by rapid blood loss, massive hemoptysis, shortness of breath, tachycardia and hypotension) [13].

Cardiac structures

If the chest tube is advanced too far, the tip may rest too close to the mediastinum, resulting in compression of nearby structures [13]. Although rare, it can lead to hemodynamic instability [13]. There have also been cases of penetration of cardiac structures

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Have you ever encountered a situation in which a chest tube was placed emergently? What was going on with the client?

- When reviewing a client’s medication list, what information may potentially halt immediate placement of the chest tube?

- Why might a chest tube be removed and placed in a new area?

- Your client has a 2 cm pneumothorax. Is a chest tube indicated?

- What the mechanism behind why a chest tube may cause hemodynamic instability?

Pain

Some pain is associated with chest tube placement. At the very least, providers will provide local anesthetic to numb the area while the tube is inserted. Sometimes, clients are also given IV pain medicine or sedation during placement. Clients may also experience pain while the chest tube is in place, so providers will often prescribe PRN analgesia to improve comfort. Some studies have suggested that large bore chest tubes are generally more painful than smaller ones [7][12]. Remember to encourage mobility. A client’s pain will need to be assessed, managed, and controlled.

Fistula

Bronchopleural fistula is both an indication for and potential complication of chest tube placement [13]. A fistula is an abnormal pathway or tract that forms between two structures, in this case between the pleural space and the bronchial tree. A chest tube may benefit a client if a bronchopleural fistula already exists [13]. However, if a fistula forms as a result of the chest tube itself, it is associated with high morbidity and mortality [13]. Client symptoms of fistula include dyspnea, hypotension, cough, and persistent air leak [13]. Timely chest tube removal can help prevent the formation of a fistula because it limits tube erosion [13].

Bleeding

Providers must be careful when placing chest tubes because the space between each rib contains a vein, artery, and nerve [13]. Although rare, cases of hemorrhage and death have been reported as a result of chest tube placement. Luckily, abnormal bleeding is usually apparent right away. However, early diagnosis can be missed if the tube compresses the artery in such a way that it prevents any bleeding while in place [5].

Recurrent Pneumothorax

One of the worst complications is recurrent pneumothorax, simply because it means the chest tube has failed. A new pneumothorax is more likely to occur when the tube is pulled too early and the lung has not properly re-expanded [13]. It can also be caused by an air leak or if air enters the pleural space during tube removal [13]. If the recurrent pneumothorax is small and the client is asymptomatic, it can typically be managed with follow up imaging and close observation. Otherwise, the chest tube will have to be reinserted.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Like all procedures, chest tubes are not without risk. Think about the complications above. What signs and symptoms might you see if these are encountered?

- A client just had a large bore chest tube placed. What type of medication might you anticipate on the client’s prescribed medication list?

- Considering the anatomy of the rib cage and surrounding structures, why are clients at risk of hemorrhaging after chest tube placement?

- Why might a client have a recurrent pneumothorax after the chest tube was just removed?

- What other chest tube complications have you encountered in your practice?

Where Are Chest Tubes Placed?

As previously mentioned, there are several different techniques used to place chest tubes: the blunt dissection technique for large bore tubes, Seldinger technique for small bore tubes, and the Seldinger technique with a peel-away dilator for tunneled chest tubes. Interestingly, these chest tube techniques can be performed just about anywhere: the operating room (OR), interventional radiology (IR), and the client’s bedside.

Operating Room

Chest tubes are usually placed in the OR after cardiothoracic surgery. The tube should be positioned no lower than the 5th intercostal space along the midaxillary line to avoid injury to the diaphragm [13]. The second intercostal space at the midclavicular line is an alternate site. However, it is never the first choice because the tube must be driven through the pectoralis muscle (ouch) and it is more likely to produce an ugly scar [5].

Mediastinal chest tubes are commonly placed after cardiac surgery to facilitate drainage of blood and other fluid from the pericardial and pleural spaces [13]. The goal is to prevent cardiac tamponade (compression of the heart due to fluid accumulation) and pleural effusion. These tubes are easy to identify because they emerge from the mediastinum.

Interventional Radiology (IR)

Interventionalists have the advantage of using imaging to assist with chest tube placement. Ultrasound, CT and fluoroscopy (live x-ray) may be used. Imaging allows the provider to observe the chest tube as it enters the body, which helps ensure proper placement.

When placing a chest tube for the treatment of pneumothorax, the provider often uses fluoroscopy for guidance. The pneumothorax is visualized on the monitor while the tube is positioned. Using the Seldinger technique, the final catheter is threaded over the wire to rest in the pleural space.

Interventional radiologists are commonly enlisted to place drainage tubes for the management of empyema or lung infection [9]. CT is the modality of choice because it allows better visualization of surrounding structures than fluoroscopy. The provider will take frequent CT scans while a wire is guided into place, then thread the catheter over the wire into the infection . Small bore tubes have been shown to be effective in the drainage of thicker fluids, like pus [7].

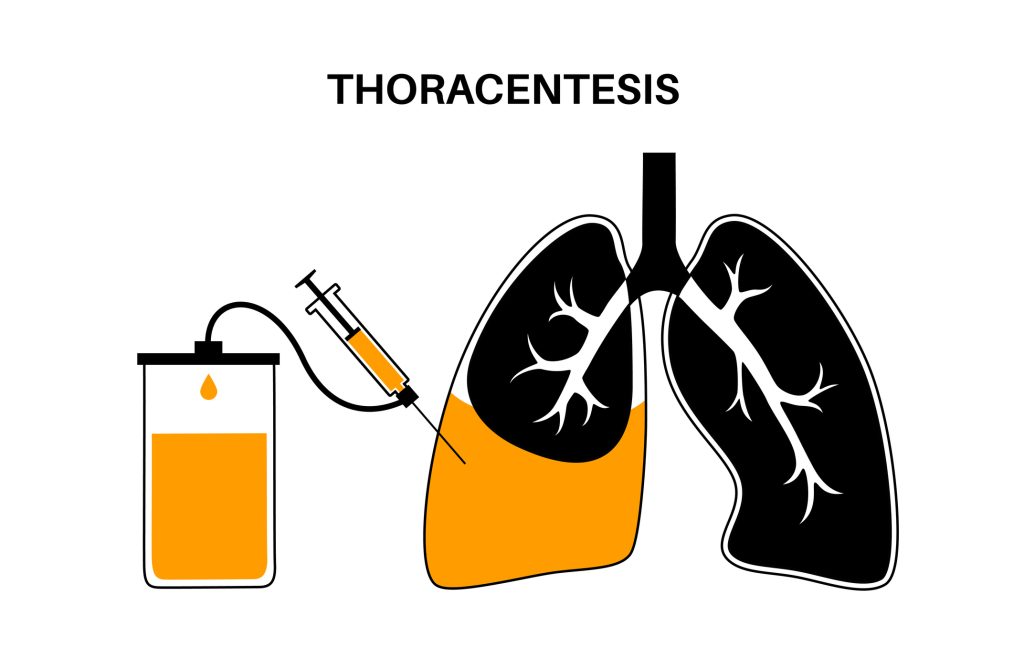

Finally, approximately 50 – 55 % of clients with cancer (with pleural involvement) develop malignant pleural effusion [23]. Breast, lung, and hematological malignancies are the main cancers associated with malignant pleural effusion [23]. At first, these recurrent effusions may be treated with thoracentesis, a procedure in which the interventional radiologist positions a small catheter into the pleural space, where it remains temporarily to allow pleural fluid to drain. After drainage has ceased, the catheter is removed and a dressing is applied.

Figure 6. Thoracentesis Procedure

Over time, malignant effusions require drainage more frequently, which can be hard on the client [23]. Thoracentesis provides only short-term relief of symptoms. Tunneled chest tubes are a more long-term alternative for malignant pleural effusion. The catheter contains a special cuff and is tunneled under the skin to minimize the risk of infection. Prior to placement, the interventional radiologist will use ultrasound to locate the effusion.

Bedside

Providers often insert chest tubes at the bedside. After discussing the risks and benefits of the procedure with the client, providers should obtain informed consent. Nursing staff would be required to assemble the appropriate supplies and be available to assist as needed. Full aseptic technique is required, so medical staff should wear gowns, gloves, masks and use sterile drapes [5].

Chest tube insertion is made much simpler if the client is positioned appropriately. The head of the bed should be raised to 45-60 degrees with the client resting in the supine position and slightly rotated. The ipsilateral arm (‘same side’ arm) is placed behind the neck or head so it is out of the way, providing easy access to the chest.

Image 2. Chest Tube Insertion Procedure

For posterior fluid collections, the client should sit on the side of the bed with the provider standing behind [5]. The position can be made more comfortable by allowing the client to rest their arms upon a side table. Bedside ultrasound will allow the provider to visualize any fluid collections.

Note: In all cases, post-procedure x-ray is required as soon as possible to confirm chest tube placement and to verify the presence or absence of complications from the insertion.

Image 3. Large right-sided pneuthorax (notice the right lung is smaller/compressed and there is large amount of space in the area around it) Remember that chest radiographs are flipped, thus this is the client’s right side. This lack of lung marking is due to a pneumothorax – thus the lung is compressed by air in the pleural space)

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- In what area of the hospital are chest tubes primarily placed?

- In clients with recurrent pleural effusion, chest tube placement is often second choice to which procedure?

- Clients with which condition often have recurrent pleural effusions, requiring frequent drainage of the pleural space?

- A provider asks you provide supplies so they can place a chest tube at the bedside. Is placement of a chest tube at the bedside appropriate?

- Have you ever witnessed a chest tube placement? If so, which way was the client positioned?

Chest Tube Drainage Systems

After a chest tube is in place, it must be attached to a drainage system to facilitate the removal of excess fluid and promote lung reinflation. There are four basic types of drainage systems: Heimlich valves, three-compartment systems, digital systems, and vacuum bottles.

Heimlich Valve

A Heimlich valve is a one-way valve shaped a bit like a thin cylinder that attaches to the distal end of the chest tube. It is called a one-way valve because air is permitted to flow only one direction: out.

The valve itself is composed of a rubber flutter that occludes with inspiration to prevent air from entering the chest. The flutter opens during exhalation to allow the trapped air to escape the pleural space. The pneumothorax shrinks slowly over time with each breath. Heimlich valves are more commonly used for ambulatory clients when suction is not required [5][17].

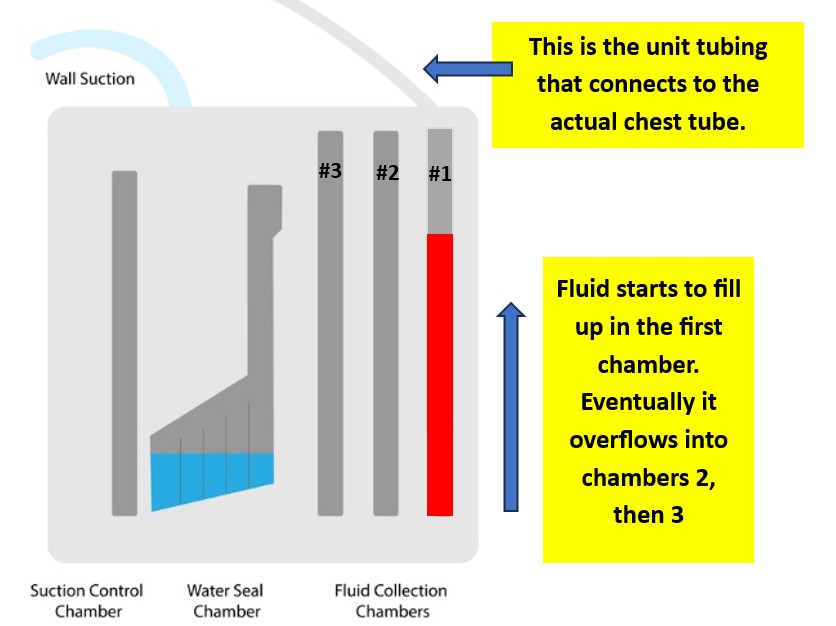

Three-Compartment System

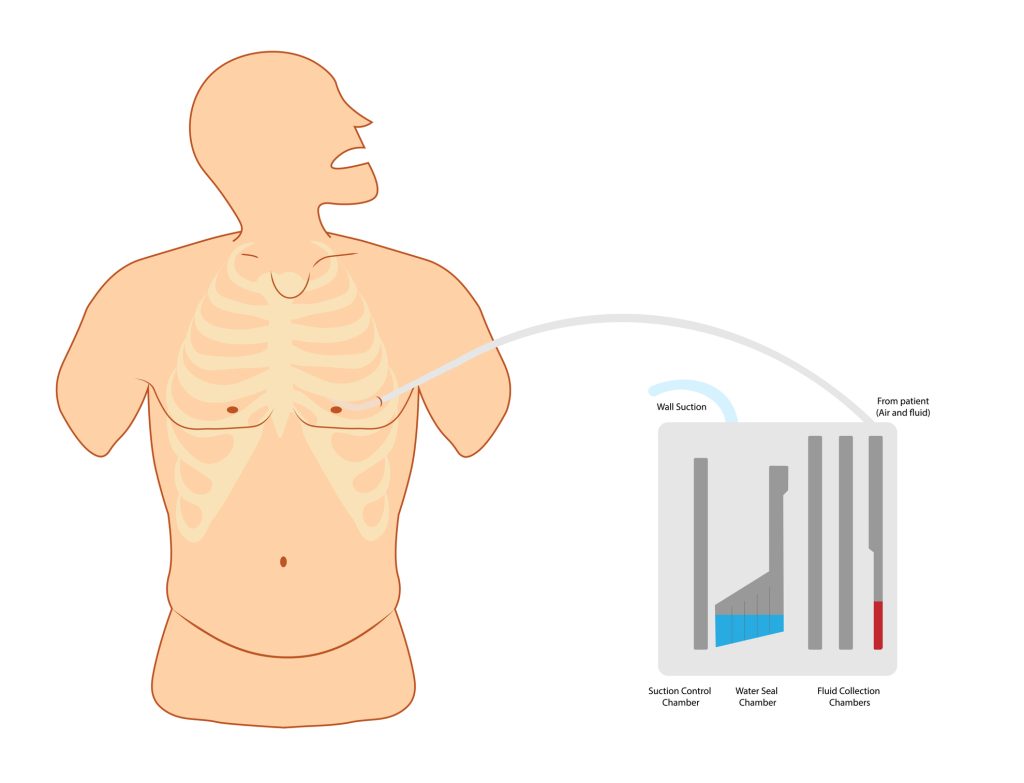

Like the name suggests, three-compartment systems contain three interconnected chambers: the collection chamber, water seal chamber, and a suction chamber. The collection chamber fills with air or fluid that drains from the chest tube. The water seal uses a column of water to prevent air from flowing into the pleural space with inhalation [5][17]. Finally, the suction chamber allows the provider to adjust the level of suction against the chest tube.

If needed, the drainage system is attached to a wall regulator to apply active suction [5]. Alternatively, these drainage systems can also be set to drain by gravity if the device is positioned below the chest [5][17]. These drain systems require careful observation for air leaks.

Figure 6. Chest Tube Drainage System

Digital Drain System

A more modern approach to chest tube management, digital systems use a computer to monitor drainage, air leaks, and pleural pressure [5]. All measurements are calculated internally and displayed on a screen. They do not require wall suction, so clients may ambulate with ease [5]. Because they are more compact and basically manage themselves, some clients are discharged with their chest tube in place, resulting in shorter hospital stays overall [5]. Digital systems are typically used for clients who develop a pneumothorax after thoracic surgery.

Vacuum Bottle

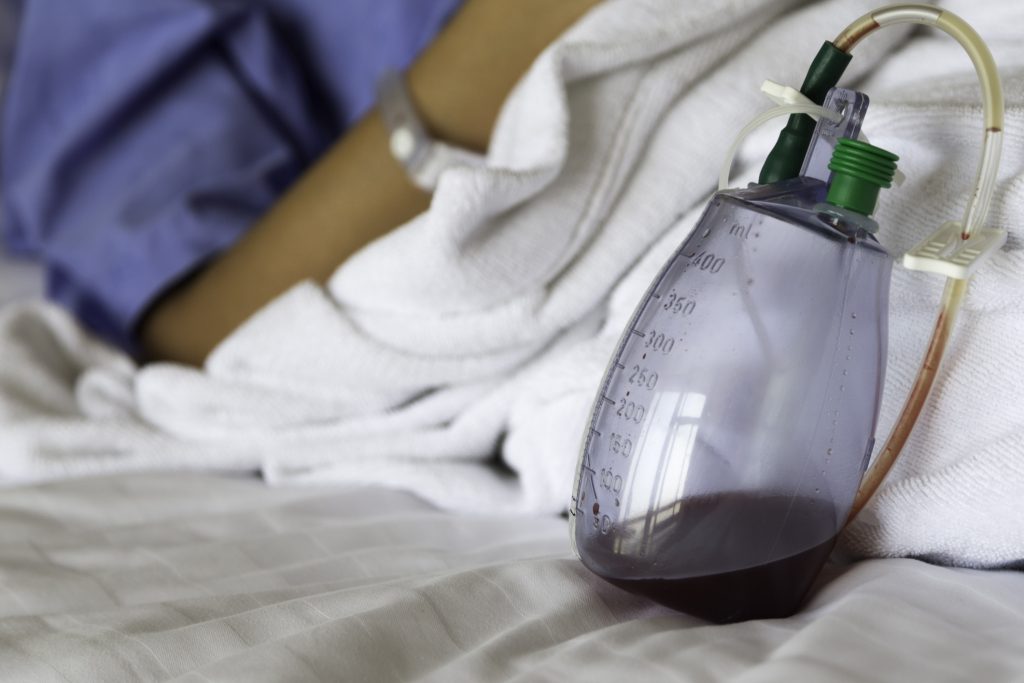

Remember, tunneled pleural catheters are commonly used to drain recurrent pleural effusions associated with malignancy [24]. Instead of constant suction and drainage, pleural fluid is allowed to accumulate and then drained periodically as needed. Frequency of drainage ranges from occasionally to multiple times a week. The tunneled catheters are equipped with a special one-way valve that opens and drains when a vacuum bottle is attached [5].

Image 3. Pleural catheter drainage bottle

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Think about the different types of drainage systems. What are the pros and cons of each system?

- How does the troubleshooting differ for each system?

- If a chest tube is not connected to suction, how can you facilitate the flow of fluid through the system?

- A client requires continuous suction of the chest tube. Is a Heimlich valve indicated in this situation?

- When are pleural catheters indicated?

Nurse Roles and Responsibilities: How to Manage Chest Tubes

It is the responsibility of the nursing staff to monitor chest tubes and report any potential malfunction. Because clients with chest tubes may reside in virtually any hospital department (or even as an outpatient), it is essential that nurses feel comfortable around them. Chest tube management includes observing and maintaining the insertion site, recording output, and managing the drainage system.

Observe the Client

Perhaps most importantly, the nurse should observe the client. Check vital signs as ordered by the provider or facility policy. Assess for pain. Some discomfort is expected after chest tube placement. Provide pain medicine as needed. Auscultate breath sounds frequently and encourage deep breathing, especially during the post-procedure period. Diminished breath sounds, changes in vital signs and increased work of breathing could indicate the re-accumulation of air or fluid in the pleural space.

Maintain the Insertion Site

Chest tubes are commonly sutured to the skin to hold the tube in place. The insertion site is covered with a dressing to protect the area. Dressing changes occur as ordered by the provider or are dictated by facility policy. Most chest tubes require an occlusive dressing, meaning the dressing should adequately cover the site and be well-secured, which reduces the risk of developing an air leak [13]. Expect to change the dressing if it becomes soiled. Nurses should observe the insertion site frequently for signs of infection, including fever, redness at or around the site, swelling, warmth, and purulent drainage.

Image 4. Chest Tube Site with Dressing

Although they are sutured in place, there is a risk for dislodging the chest tube if it is pulled too hard. Securing the tube to the client’s side with a piece of tape is one way to reduce the risk of dislodgement. Advise the client to ask for help when getting out of bed.

Record Output

The nursing staff is also in charge of observing and recording chest tube output. The frequency of recording the output is dictated by nursing judgment and written orders from the provider or facility policy. Drainage fluid is often bloody, serosanguinous (pink), or purulent, depending on the reason it was inserted. Whatever the color, it should lighten in color and lessen its drainage amount over time. All drainage is contained within this system, meaning the container cannot be emptied. Instructions vary between facilities, but it is common practice (for three-compartment systems) to document the amount of drainage directly onto the canister by marking the level of output with a pen or marker each shift. When full, the drain unit is removed and a new, clean one is attached. For indwelling pleural catheters, the glass drainage bottle is never emptied, but simply exchanged for a new one. The pleural output amount is determined by simply looking at the measurements on the bottle prior to disposal. Check your facility policy on when to call the provider for excessive drainage. Always call the provider for excess drainage when there is a change in the client’s vital signs or signs of a worsening condition.

Manage Drain Systems

Heimlich Valve

Nurses should assess that the Heimlich valve is securely attached to the distal end of the chest tube. The one-way flutter valve allows air to leave the chest but prevents air from seeping back inside. It does not require suction, so the client may move around freely. Heimlich valves do not possess a collection chamber, rather, any drainage will freely leak from the distal end of the valve. Thus, the Heimlich valve is not the system of choice for clients with significant drainage.

Three-Compartment System

Again, these are the most commonly used systems. They should be positioned below the client’s chest at all times. The nurse is responsible for monitoring the three compartments: collection chamber, water seal, and suction. As discussed above, the nurse will simply document any drainage that collects in the collection chamber.

Figure 7. Three-Compartment Chest Tube System (designed by NCC content team, 2025)

The water seal serves two functions: to prevent outside air from flowing into the chest and the detection of air leaks. An air leak within a chest tube may indicate a serious problem. The water seal should be easy to find. When the water seal is functioning correctly, the water level will tidal, or ‘rise and fall’ (soft bubbling), with breathing. If the nurse observes intermittent or constant bubbling within the water seal, an air leak is present [13]. The most severe type of leak is a continuous air leak which is observed throughout the entire respiratory cycle. All air leaks need to be reported to the provider immediately and the client needs to be reassessed for further signs of respiratory distress. Digital draining systems are able to quantify the leak, display 24-hour monitoring data, and automatically unclog the tube without the need for clinician intervention [16]. A persistent air leak can be caused by either an alveolar-pleural fistula or bronchopleural fistula [21].

Chest tubes often require suction to help gently pull excess fluid and air from the body. Three-compartment systems are equipped with a dial that allows staff to set the level of suction, usually between 0 and -40 cm H2O. The provider’s orders or facility policy will dictate the level at which suction should be set. Part of the nurse’s assessment is verifying that the suction dial is set correctly. Additionally, nursing staff should check that the suction tubing is connected securely to the wall suction regulator.

Digital Drain System

Thanks to technology, digital drain systems are pretty easy to manage. The device collects and displays all of its data to the nurse, including the amount of drainage, intrapleural pressure, and the presence of any air leak. It simply needs to be recorded.

Tunneled Catheters

Tunneled pleural catheters should be clamped unless they are being drained. These catheters contain a one-way valve that will not open unless a vacuum bottle is attached. Tunneled catheters are usually managed at home by the client, a willing family member, or trained a home health provider, thus the client and family may require extensive education prior to discharge.

Clamping the Tube

With the exception of tunneled catheters, as a general rule, chest tubes should not be clamped unless troubleshooting air leaks (clamped briefly), replacing the drain system, removing the chest tube, or ordered by the provider [17]. If an air leak is present, a clamped tube can lead to tension pneumothorax [13]. There is no need to clamp a chest tube during client transportation or ambulation. If the drainage system is positioned below the chest as indicated, it will continue to drain with gravity after suction is turned off [17].

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- You receive an order to “start chest tube suction.” At what setting should you set the suction?

- You are caring for a client with a chest tube. The drainage output darkens in color and increases in amount over time. What is your next action?

- How would you drain a pleural catheter?

- How much experience do you have with digital drain systems? If so, what difficulties or complications have you encountered, if any?

- When are the only times you can clamp a chest tube?

Chest Tube Troubleshooting: When to Call the Provider

Like anything else, chest tubes are prone to complications. It is essential for nurses to be able to identify a malfunctioning tube quickly and know when to alert the provider. A worsening pneumothorax can lead to a longer hospital stay for the client, or at worst tension pneumothorax and death.

Tube/Drain Malfunction

Chest tubes should be assessed regularly by nursing staff. The chest tube must be well-connected to the drainage system and wall suction (if necessary). If the chest tube becomes disconnected from the drainage system, the two ends should be cleaned well with an antiseptic, like alcohol pads, prior to being reconnected [13]. You can also stick the open end of the chest tube into a bottle of sterile water or saline to quickly create a water seal [17]. Do not clamp the tube in case there is an air leak, as the client could develop a tension pneumothorax [13]. If the tube is completely pulled out from the clients’ chest, immediately apply pressure and apply a sterile petroleum impregnated gauze over the site and call the provider immediately [15].

Infection

Infection is always a risk when a foreign body is present. Because chest tubes allow direct access into the chest cavity, it is essential to watch closely for any signs of infection. Infection may develop at the insertion site or inside the chest cavity (empyema/abscess).

Signs of infection at the insertion site include fever, redness, swelling, warmth, or purulent drainage. The site needs to be kept clean and soiled dressings should be replaced quickly and efficiently.

Clients with chest tubes who also have pleural effusions are at higher risk of developing empyema [13]. Chest tubes are considered a “clean contaminated” procedure, meaning the chest cavity is accessed cleanly, but a risk for contamination remains as long as the tube is in place [13]. The risk of empyema after chest tube insertion is as high as 25% in some populations. A nurse might suspect the development of empyema/abscess if the client exhibits symptoms of infection: fever, tachycardia, respiratory distress and purulent drainage from the chest tube. A prompt call to the provider is warranted.

Kinks & Clots

The smaller the chest tube, the more likely it is to become clogged or kinked. Sometimes it is easy to spot a problem with a simple inspection of the entire apparatus. Pay particular attention to areas of the tubing covered with tape, such as the insertion site or taped connections. Some facilities may require you to tape the connections in such a way that you can still see inside of the tubing (follow your facility’s protocol on taping instructions). Straighten out the tubing when clients are lying in bed or sitting in the chair.

Pay close attention to the drainage system. A digital system or three-compartment syndrome will alert you if there is a problem. A digital system will literally sound the alarm in the event of a kink or clot because it monitors pressures. Three-compartment systems are not fitted with alarms, so they require closer observation to detect an issue. Earlier, it was mentioned that it is normal for the water seal in three-compartment systems to tidal with breathing or coughing. If the water seal is not tidaling with breaths, you may have a kink or clot. The water seal is not tidaling because the tube cannot drain past the blockage.

Kinks are easy to fix: simply straighten out the tube or resolve kinked connections. Clots can be a little more difficult to handle. Luckily, ⅔ of clots resolve themselves [13]. Historically, providers have used techniques such as milking or stripping the tube to help remove clots. Milking or stripping refers to moving clots through the tube into the collection canister by using your non-dominant hand to hold the tube at the skin insertion site and your dominant hand to gently squeeze the tube between your thumb and index finger moving along the tube towards the unit [19]. While milking may still be in practice for some other types of drains, it’s considered a questionable procedure for chest tubes. Prophylactic milking/stripping has not shown any tendency to prevent clots from forming [13]. Also, these techniques have actually been shown to cause harm by increasing intraluminal pressures (can cause a life-threatening pneumothorax) as well as increasing pressure within the pleural cavity, resulting in increased bleeding, tissue entrapment, and dysfunction of the left ventricle [17][13].

What do you do if you see a clot then? If the clot is located in the drain system tubing, simply replace the system. Attach a new system and remove the affected tubing. If that doesn’t resolve the problem, notify the provider. Chest tubes can also become kinked inside of the client, so the provider may order a chest x-ray to confirm proper tube placement [8].

Loss of Suction

Ensure that the drain tubing is securely attached to the wall suction regulator and that the tubing is unclamped. The regulator should be turned on. Check that the suction dial on the drain system is set to the appropriate suction setting and that the suction is continuous, not intermittent. If all connections are appropriate, the wall regulator or drain system is malfunctioning and should be replaced. Maintaining appropriate suction is critical, as too little suction will prevent lung re-expansion, while too much suction can damage lung tissue.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- You enter a client’s room who has a chest tube and notice the wall suction is set to ‘intermittent’. What is your next action?

- What may be happening if the water seal on the chest tube unit is not tidaling?

- The provider asks you to ‘milk’ the chest tube drain. What is your next action?

- You notice a clot in the tubing of the drain system. What is your next action?

- What might happen if the chest tube suction is set too high?

Drain System Malfunction

The best course of action is to replace the drain system and re-assess the problem. If it was truly an issue with the drain system it should resolve by replacing it.

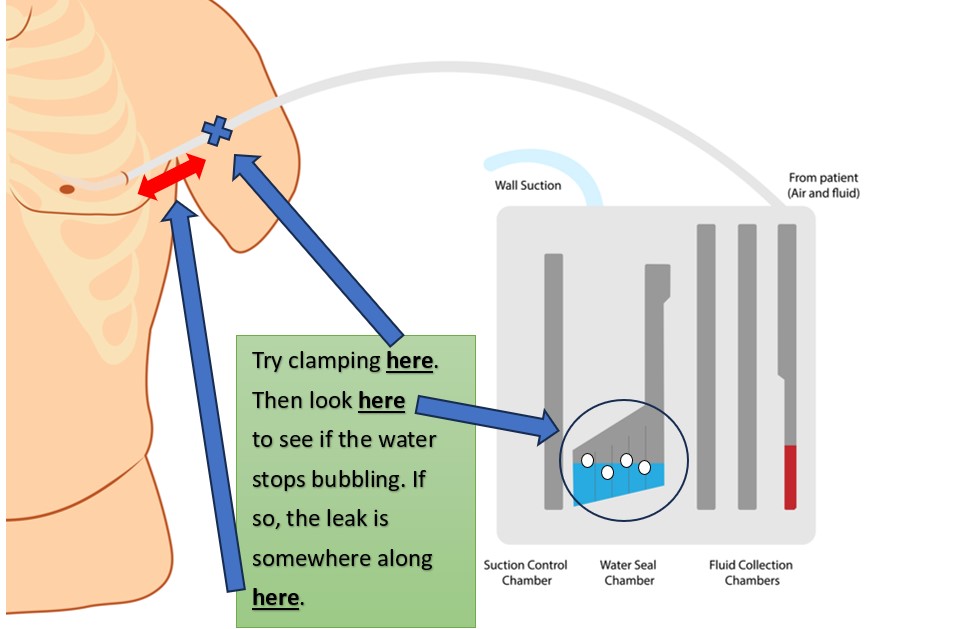

Air Leak

The easiest way to assess for an air leak is to observe the drainage system. Again, a digital system will alarm if it detects a problem. With a three-compartment system, an air leak will cause intermittent or constant bubbling within the air-leak detection compartment of the water seal. Air leaks are a concern because they allow air to flow back into the pleural space [13]. The whole point of the chest tube is to get the air out of the chest. Air leaks can occur in a couple places: at the insertion site or within the tubing/drain system [13].

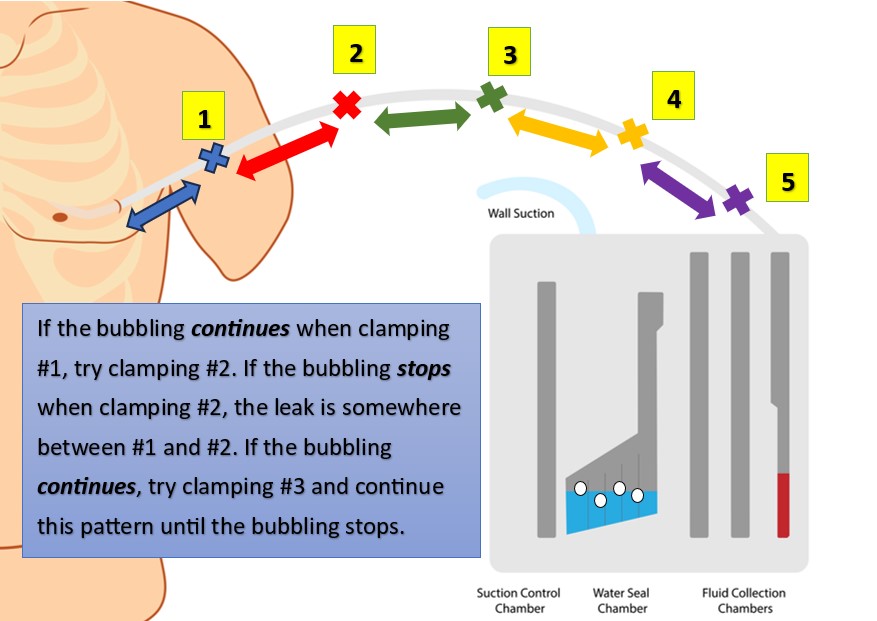

If an air leak is observed in the water seal chamber, the next step is to find out where it is coming from. This is one case in which clamping the tube (temporarily, of course) can help diagnose a problem. First, clamp the tube close to the client [17]. If bubbling within the water seal chamber continues, this means there is a leak in the tubing or drain system.

Figure 8. Testing for Air Leaks in a Chest Tube System (Part 1) (designed by NCC content team, 2025)

Figure 9. Testing for Air Leaks in a Chest Tube System (Part 2) (designed by NCC content team, 2025)

Although made of strong material, these drain systems are not infallible. Tubing can be cut or damaged accidentally, and it may not be easy to spot. Assess the tubing for cuts or holes. Ensure all connections are secure, as loose connections are an easy way for air to sneak inside. Replace the drain system if the tubing or container is damaged.

On the other hand, if you clamp the tube and the air leak disappears from the water seal, this means air is leaking near the client [17]. In this case, the leak stems from the insertion site or somewhere inside the chest [17]. An air leak at the insertion site occurs because the dressing is insufficient or the hole is too big. This is why an occlusive dressing is a must. Apply new petroleum gauze and cover with a sterile, occlusive dressing at the site where the tube enters the skin [17]. Remember, if the chest tube was just placed, the surgeon must change the first post-op dressing, so simply reinforce the dressing or notify the provider. Reinforcing the dressing prevents air from leaking into the chest at the skin.

Unfortunately, sometimes the skin site is too large relative to the tube itself, meaning the tube is too small for the skin incision that was created [13]. The tube should fit snugly into the skin incision, without gaps. If you suspect the skin incision is too large, notify the provider. Often, a simple stitch can tighten any loose skin at the insertion site [13].

Finally, if you have accounted for all of the potential problems listed above and an air leak remains, contact the provider. As mentioned earlier, potential causes of persistent air leak include alveolar-pleural fistulas or bronchopleural fistulas as well as residual pneumothorax [2][21]. Notify the provider right away if all attempts to resolve an air leak have failed.

Tube Dislodgement

Sometimes, the tube comes out despite every precaution. It may be pulled out partially or completely. After a partial removal of the tube, quickly and calmly secure the tube to the client with a new dressing and tape. Obtain a set of vital signs and assess for pain and any new symptoms, such as shortness of breath or dyspnea. Notify the provider immediately. Follow up imaging (usually an x-ray) may be ordered to determine chest tube location and assess for any residual pneumothorax.

If the tube is pulled completely out, follow your facility’s protocol on immediate actions. However, it may be recommended to put on a clean pair of gloves and quickly cover the insertion site with your hand to prevent air from flowing into the chest. Stay with the client and call for help. When help arrives, ask a colleague to get the necessary supplies for a new occlusive dressing: petroleum gauze, dry sterile gauze, and tape. Apply the dressing and notify the provider immediately (be sure to tape only 3 sides of the gauze so air can escape when the client breathes; not doing so can lead to a tension pneumothorax) [17]. If the client is in distress, call for help. Remember, chest tubes can be placed at the bedside pretty quickly in an emergency. And try to stay calm!

Under normal circumstances, chest tubes are removed once drainage has ceased or become serosanguinous, no signs of bleeding are present, output is less than 150 cc to 400 cc over 24 hours (may be different per facility protocol), breath sounds return to normal, chest rises and falls symmetrically, and/or imaging shows a resolution of the pneumothorax [17][20]

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Think about the different types of complications that can occur. How would you react and manage each complication?

- When would you call the provider for further assistance?

- What are some life-threatening complications that can occur as a result of chest tube malfunction?

- If you notice that an air leak is occurring at the chest tube insertion site, what simple solution (performed by the provider) may correct this type of leak?

- What criteria must be met before a chest tube is removed?

Review on Chest Tube Emergencies/Urgencies for Nurses

Just like nursing school, it’s one thing to learn the material, but what happens when you encounter issues in the real world of nursing? We’ve reviewed chest tubes thoroughly, but what happens when you walk into your client’s room and a chest tube emergency happens? Let’s do a quick recap on what to do when you encounter certain chest tube complications [17].

Respiratory Distress

While typical signs/symptoms of respiratory distress are obvious (such as hypoxia, shortness of breath, and decreased breath sounds), other clinical manifestations may include asymmetric chest rise when breathing, tracheal deviation, chest pain, hypotension, tachycardia or bradycardia, and subcutaneous emphysema around insertion site or neck (this will be discussed shortly). Here’s what to do if your client with a chest tube has respiratory distress [17]:

- Administer oxygen

- Ask for emergency assistance if needed (call a respiratory therapist or emergency team)

- Check the chest tube system for leaks, occlusions, or kinks

- Notify the provider (they may order an urgent chest x-ray)

Air Leak

As discussed, an air leak can compromise the chest tube system, ultimately inhibiting its function, potentially worsening the client’s condition. Here’s what to do if you notice bubbling in the water seal chamber (or hear a hissing sound at your client’s chest) [17]:

- Don’t panic! The leak is either at the insertion site, in the tubing, or at the actual chest tube unit. Simply do a little troubleshooting.

- Clamp the chest tube (briefly) starting near the client’s chest. If the bubbling/hissing stops, congratulations, you’ve found the leak! Simply reinforce the insertion site dressing and notify the provider.

- If the bubbling/hissing does not stop, move down the tube, clamping briefly at different spots along the way until the bubbling/hissing stops. If the leak is in the tube, check the tube for holes or cracks, then seal these areas (can use tape, per your facility’s protocol) or just change the tube entirely.

- If the bubbling/hissing still doesn’t stop, your problem is with the actual unit/canister which is the easiest fix! Simply change the unit (don’t forget to document the drainage output that’s in the old unit before disposal).

- If you still have trouble, notify the provider

Accidental Dislodgement

Tube dislodgement occurs when the actual chest tube comes out of the client’s chest. When it comes to tube dislodgements, you should follow your facility’s protocol, but there are some standard actions all nurses should take. Here’s what to do if your client’s chest tube accidently comes out [17]:

- Don’t leave the client! Call for help and ask a colleague to notify the provider and gather supplies for you (sterile occlusive/petroleum dressing, sterile 4×4 gauze pads, and tape). Ideally, these supplies should always remain at the bedside in case of emergencies.

- Call an emergency team if your client is in distress.

- Cover the site right away (even if you must use a gloved hand in the meantime until your supplies arrive – check for the appropriateness of this action with your facility’s protocol). Once your supplies arrive, cover the site with the occlusive dressing first, then the 4×4 gauze, and cover with tape on 3 sides only (air must be able to escape the puncture site when the client breathes to prevent it building up in the pleural space, causing a tension pneumothorax).

Accidental Disconnection of Tubing

Tube disconnection occurs when tube connections aren’t secured well or are accidently pulled apart (but the actual chest tube remains in the client’s chest). Here’s what to do if this happens [17]:

- Don’t panic! But you have to move quickly when this happens.

- Call for help because you’ll need to change the whole drainage system.

- While you wait for supplies, clamp the tube (briefly) near the client’s chest OR place the distal end of the chest tube in a container/bottle of sterile saline (to keep the water seal). Sterile saline is another great item to keep at the bedside for emergencies.

- Change the whole drainage system

- Notify the provider

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Your client with a chest tube suddenly is short of breath, which action should you take?

- After troubleshooting an air leak, you note the leak is due to a small hole in the tubing. How can you correct this leak?

- A nurse is providing care to a client with a chest tube when the tube accidently comes out of the client’s chest. The nurse quickly runs to the supply room for an occlusive dressing. Was the nurse’s action appropriate?

- When the nurse (in the question above) is applying the occlusive dressing to the puncture site, how should they tape the dressing?

- What are some reasons why the drainage tubing may become disconnected from the chest tube?

Subcutaneous Emphysema

Subcutaneous emphysema (often described as a crackling sensation felt under the skin upon palpation) occurs when air builds up in the tissues because there’s an air leak in the chest cavity. You might ask, “Why would I even think to palpate my client’s chest?” How will I know they have subcutaneous emphysema just by looking at them?” You may notice the chest enlarging/swelling in a certain area or at the base of the neck. That’s when you can palpate the area. This condition, if left untreated, can spread and cause respiratory and cardiovascular collapse [11]. Here’s what to do if you feel the crackling sensation [17]:

- Notify the provider right away. The provider may simply ask you to monitor the area. They may also order a chest x-ray to assess the leak

- Mark the border of the area on the skin where you see the enlargement or where the crackling is felt (according to your facility’s protocol). By marking the border, you can monitor if the area is spreading. Typically, subcutaneous emphysema will gradually resolve on its own once the cause is addressed.

Drainage Stops

First and foremost, not every chest tube drains fluid. Some are placed to remove air from the pleural space. Be clear on why your client’s chest tube was placed before expecting to see fluid output. For chest tubes placed to drain fluid, the tube can become clogged with thick drainage or a blood clot. If you notice drainage suddenly stops, this is cause for concern as the drainage system’s function is now compromised, which can worsen the client’s condition. If the tube was just placed (within 24 hours), the culprit may be a blood clot. Here’s what to do if drainage suddenly stops [17]:

- Check the tubing for kinks and dependent loops. Straighten the tubing for optimal flow.

- If there’s still no flow, ensure the tube system is below the level of the chest to promote gravity flow.

- If you’re still having trouble with the flow, reposition the client in an upright position, if appropriate, to encourage gravity flow. It’s possible the tip of the chest tube within the client’s chest is simply not in a drainage pocket. Repositioning the client should help.

- If repositioning doesn’t help, it’s time to notify the provider

Suction Control Chamber Not Bubbling or Bubbling Too Much

Bubbling in and of itself is not a bad thing when it comes to chest tubes. Problems arise when the bubbling occurs in certain areas of the chest tube unit or when the bubbling intensity is too high/vigorous. For example, vigorous bubbling in the suction control chamber may require you to frequently add more saline because it’s evaporating faster. The suction control chamber (NOT the water chamber) should be tidaling (soft bubbling) with breaths. If you notice no tidaling at all or you notice vigorous bubbling, here’s what to do [17]:

- Make sure the suction tubing is connected to the suction source

- Make sure the suction is actually turned on and set to the ordered suction amount

- If you still have trouble, you may need to change out the unit (but follow your facility’s protocol).

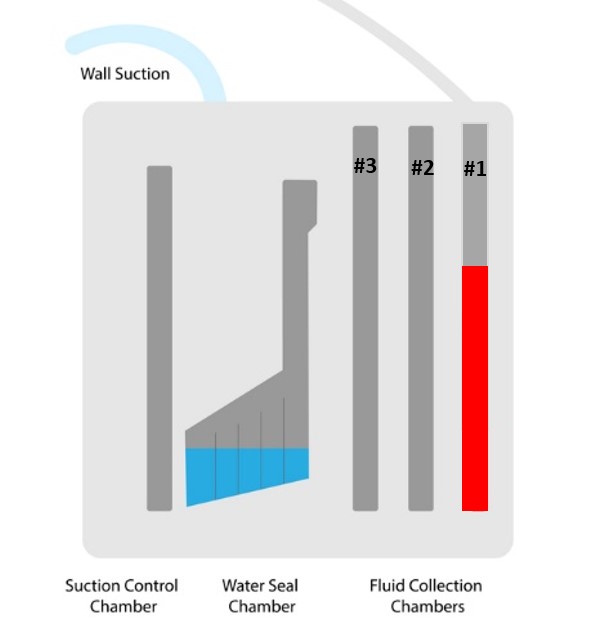

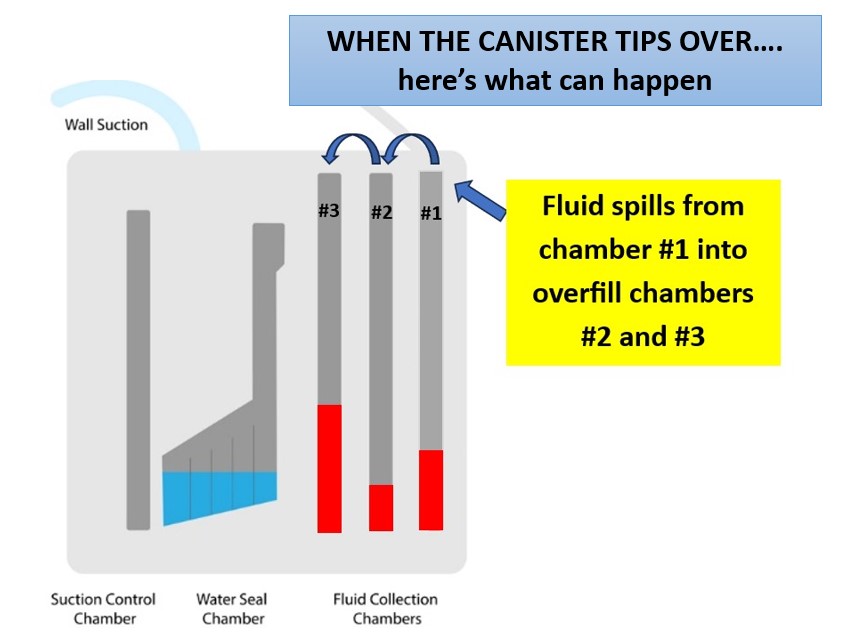

Drainage Container Tips Over

Accidents happen. Your client’s chest tube may accidently tip over during activity. While this isn’t necessarily an emergency, it’s something that should be addressed right away. Here’s what to do when this happens [17]:

- Don’t panic! This is a quick fix and doesn’t necessarily compromise the client’s condition.

- Check to see if the tubing is still connected to the canister. If so, simply position the unit upright again! As long as everything is still connected, the system is still sterile. If connections have come loose, you may need to change the unit.

- Check the fluid level in the water seal for the correct volume. If its different, replace the fluid as ordered.

- Look at the collection chambers in the unit. If fluid/output has spilled into the overfill chambers, it may be better to simply change the unit because now it will be difficult to monitor the drainage output amount (check with your facility’s protocol if this is appropriate) (see figure below)

- For next time, consider using the attached floor stand that typically comes with the unit if it wasn’t used the first time OR consider attaching the unit to an IV pole if the client is ambulatory (according to your facility’s protocol).

Figure 10. Chest Tube Drainage Container BEFORE tipping over (designed by NCC content team, 2025)

Figure 11. Chest Tube Drainage Container AFTER tipping over (designed by NCC content team, 2025)

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some actions you can take if the chest tube drainage suddenly stops?

- What is the cause of subcutaneous emphysema?

- How might you know that a client has subcutaneous emphysema by observing them?

- You notice gentle bubbling in the suction control chamber of your client’s chest tube when they breathe. Should you call the provider? Why or why not?

- If the drainage canister of the chest tube tips over and the fluid in the first chamber remains unchanged, is it necessary to change the canister?

Chest Tubes – Frequently Asked Questions

Why raise the arm for chest tube insertion?

Regardless of the client’s position, sitting up, or lying in a supine position (preferred), the client’s arm on the side of the chest tube insertion should be abducted and flexed with the hand above the head to expose the proper area of insertion. The main reason to place the client in this position is to ensure easy access to the chest for clean and proper insertion.

How do I change a chest tube dressing?

Most chest tubes require an occlusive dressing meaning the dressing should adequately cover the site and be well-secured, therefore reducing the risk of developing an air leak.

- Gather necessary materials, including:

- Sterile gloves

- Drain sponges (split gauze)

- 4×4 gauze

- Petroleum gauze

- Antiseptic

- Tape

- Wash your hands with soap and water and put on sterile gloves.

- Open the packaging of materials so you can gather the materials as you need them while maintaining sterility.

- Remove the client’s old dressing. Inspect the chest tube site for redness, skin breakdown, suture condition, drainage amount and color, and if air leaks are present.

- Remove old gloves, and don new gloves.

- Clean the site with the appropriate antiseptic. Begin at the insertion site and move outward. Repeat the process additionally and allow the site to thoroughly dry.

- Place the petroleum gauze to create an air-tight seal at the insertion site.

- Place the drain sponge around the client’s chest tube. Apply two 4×4 sponges over the previous layer of dressing that covers the chest tube.

- Apply tape over the dressing. Some like to place foam tape. Make a note of the time, date, and initial of the nurse changing the dressing.

- Remove your gloves and wash your hands thoroughly.

***This is an example of a dressing change. Some facilities have protocols related to chest tube dressings. Please use this as a guide and not as fact. Please follow your facility’s protocol.

How is it determined which chest tube to use?

The decision to use a small or large-bore chest tube is made by the provider. Research shows that small-bore chest tubes are as effective as larger chest tubes for the treatment of most pneumothoraces and may be less painful. Large bore chest tubes are recommended to treat traumatic pneumothorax due to the need for the removal of blood and air

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- When a client is experiencing shortness of air, and you notice the chest tube is clamped, what do you do?

- Which is the best position of the client’s right arm for chest tube insertion of a right pleural effusion.

- Are chest tube dressing changes sterile procedures?

- Have you ever changed a chest tube dressing? If so, have you encountered an infection at the site when removing an old dressing? How did the site appear?

- The provider is preparing to remove a chest tube and asks you to gather supplies for the dressing that will be placed to the site afterwards. Which supplies do you gather?

Conclusion

Chest tubes are a life-saving intervention for the client with pneumothorax, hemothorax, chylothorax (lymphatic fluid), pleural effusion, empyema/infection, and also those recovering from major cardiothoracic surgery. The technique for chest tube placement depends on the size: large tubes are placed using the blunt dissection technique and small tubes are inserted with the Seldinger technique. Radiologists use the Seldinger technique and a peel-away dilator to insert tunneled chest tubes.

Both small bore and large bore chest tubes are effective in treating pneumothorax, hemothorax, empyema/infection, and preventing complications after surgery. The size of the tube really depends on provider preference. There are advantages and disadvantages to either size. Large bore tubes are less likely to form kinks or clots, but may be more painful. Small bore chest tubes are less invasive, but form clots much more easily. Tunneled chest tubes are a great way to provide palliative care to clients suffering from recurrent malignant pleural effusions.

While there are no true contraindications for chest tube placement, a few relative contraindications exist. Sometimes, chest tube placement is a true emergency, such as the need to treat a tension pneumothorax. In these cases, the benefits outweigh the risks. For more stable clients, providers should ensure that consent is obtained and the client’s blood is not too thin prior to chest tube insertion.

When possible, clients and their families should be aware of potential risks with chest tube placement. Bleeding, damage to surrounding structures, bronchopleural fistula, recurrent pneumothorax, and pain are some potential complications of initial chest tube placement.

Chest tubes may be placed in the OR, IR, or even at the bedside. Once inserted, the tube should be connected to a drainage system to pull air or fluid out of the chest and prevent it from returning to the pleural space. Types of drainage systems include Heimlich valves, three-compartment systems, digital systems, and vacuum bottles for tunneled pleural catheters.

Nurses are responsible for chest tube management after insertion. Roles and responsibilities include monitoring and recording drain output while continually assessing for signs of infection, air leaks, suction loss, or drainage system dysfunction. The ability to quickly identify a malfunctioning tube is essential for protecting our clients. Often, a problem is solved with a quick fix, like replacing the drainage system if the tubing becomes damaged. However, persistent questions and concerns require a prompt call to the provider.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are some teaching points you can give clients and their families about chest tubes?

- What is one reason you should contact the provider when managing chest tubes?

- Based on your specialty, what do you anticipate is the most common indication for chest tube placement you may encounter?

- After reading this course, how confident are you in caring for clients with chest tubes?

- What is the one thing that was most personally relatable to you in this course?

- How might this course improve your care of clients with chest tubes?

- What was the most interesting fact from this course? Why?

- What type of support do you anticipate clients with chest tubes may need during treatment?

- After reading this course, how might you ease a colleague’s fear about chest tube management?

- How has this course changed your perspective on chest tube management?

References + Disclaimer

- Adeyinka, A., & Kondamudi, N. P. (2023, August 12). Pediatric malignant pleural effusion. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507720/

- Adeyinka, A., & Pierre, L. (2023, July 4). Air leak. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513222/

- Avery, S. (2000). Insertion and management of chest drains. Nursing Times, 96(37), 3. Retrieved from https://www.nursingtimes.net

- Costumbrado, J., & Ghassemzadeh, S. (2023, July 4). Spontaneous pneumothorax. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459302/

- Friese, J. L. (2011). Tube thoracostomy: A review for the interventional radiologist. Seminars in Interventional Radiology, 28(1), 39-47. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1273939

- Garvia, V., & Paul, M. (2023, August 7). Empyema. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459237/

- Hamad, A. M., & Alfeky, S. E. (2021). Small-bore catheter is more than an alternative to the ordinary chest tube for pleural drainage. Lung India: Official Organ of Indian Chest Society, 38(1), 31–35. https://doi.org/10.4103/lungindia.lungindia_44_20

- Hogg, J. R., Caccavale, M., Gillen, B., McKenzie, G., Vlaminck, J., Fleming, C. J., Stockland, A., & Friese, J. L. (2011). Tube thoracostomy: A review for the interventional radiologist. Seminars in interventional radiology, 28(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1273939

- Iguina, M. M., Sharma, S., & Danckers, M. (2024, December 24). Thoracic empyema. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544279/

- Krishna, R., Antoine, M. H., Alahmadi, M. H., Rudrappa, M. (2024, August 31). Pleural effusion. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448189/

- Kukuruza, K., & Aboeed, A. (2023). Subcutaneous Emphysema. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31194349/

- Kulvatunyou, N., Bauman, Z. Zein, E., Savo, B., de Moya, M. Krause, C., Mukherjee, K., Gries, L., Tang, A., Joseph, B., & Rhee, P. (2021). The small (14 Fr) percutaneous catheter (P-CAT) versus large (28–32 Fr) open chest tube for traumatic hemothorax: A multicenter randomized clinical trial. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 91(5):p 809-813. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000003180

- Kwiatt, M., Tarbox, A., Seamon, M., Swaroop, M., Cipolla, J., Allen, C., … Stawicki, S. P. (2014). Thoracostomy tubes: A comprehensive review of complications and related topics. International Journal of Critical Illness & Injury Science, 4(2), 143-155. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.134182

- McKnight, C. L., & Burns, B. (2023, February, 15). Pneumothorax. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441885/

- Merkle, A., & Cindass, R. (2023, January 22). Care of a chest tube. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK556088/

- Nakada, T., & Ohtsuka, T. (2023). Thoracic drain management using a digital system. Journal of thoracic disease, 15(2), 219–222. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-22-1692

- Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN). (2023). Chapter 6 manage chest tube drainage systems. In: Ernstmeyer K, Christman E, eds., Nursing advanced skills [Internet]. Eau Claire (WI): Chippewa Valley Technical College. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK594490/table/ch6chesttube.T.potential_problems_compli/

- Pumarejo Gomez, L., & Tran, V. H. (2023, August 8). Hemothorax. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538219/

- Ramesh, B. A., Evans, J. T., & BK, J. Suction drains. (2023 July 4). In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557687/

- Ravi, C., & McKnight, C. L. (2022, October 3). Chest tube. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459199/

- Ruenwilai, P. (2024). Bronchoscopic management in persistent air leak: A narrative review. Journal of thoracic disease, 16(6), 4030–4042. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-24-46

- Sajadi-Ernazarova, K. R., Martin, J., & Gupta, N. (2023, August 8). Acute pneumothorax evaluation and treatment. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538316/

- Sharma, S., & Boster, J. (2024, August 12). Malignant pleural effusion. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK574541/

- Siddiqui, F., Ihle, R. E., & Siddiqui, A. H. (2023, February 8). Intrapleural catheter. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493229/

- Taweesedt, P. T., Anjum, H., Dadhwal, R., & Surani, S. (2021). Hemothorax after a renal biopsy with ablation, a rare complication: A case report and review of the literature. Cureus, 13(1), e12439. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.12439

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate