Course

Colorado Substance Use Prevention

Course Highlights

- In this Colorado Substance Use Prevention course, we will learn about Colorado State and Federal Laws governing correct prescription and monitoring of controlled substances.

- You’ll also learn evidence-based approaches to assess and manage acute and chronic pain across diverse patient populations.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of multimodal pain management strategies including pharmaceutical treatments.

About

Pharmacology Contact Hours Awarded: 4

Course By:

Sarah Schulze

MSN, APRN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

Pain can vary according to the source and intensity, as well as an individual’s age, gender, culture, and interpretation by the individual. Unfortunately, everyone will eventually experience pain. The nurse’s role is crucial in providing comprehensive patient care by evaluating and treating pain effectively.

Colorado allows a board certified and licensed advanced practice nurse to prescribe and monitor medications both in a provisional and full practice capacity, depending on the clinicians amount of experience. The state requires mandatory completion of a course on safe narcotic prescription and identification of potential substance use disorder, which is discussed in this course.

Colorado Laws Regarding Safe Controlled Substance Prescriptions

Colorado state and federal laws govern the prescribing and monitoring of controlled substances including all narcotics. The Controlled Substances Act (CSA), administered by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), regulates all aspects of controlled substance manufacturing, distribution, dispensing, prescribing and distribution. The DEA regulations offer healthcare providers specific guidelines regarding prescribing practices, record keeping practices, and monitoring (38).

At the federal level, any prescriber of narcotics or scheduled drugs must apply for and be approved to be a prescriber, which includes physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. Nurse practitioners in the state of Colorado are first granted provisional prescriptive authority, allowing them to prescribe and monitor necessary medications, including controlled substances, to clients within their scope of practice while engaged in a synchronous mentorship with either a physician or full practice APRN. The supervising role in the mentorship must be filled by a Colorado-licensed physician or APRN who is qualified to treat the same or similar patient population and the mentorship must be completed within a three-year time period.

Once the nurse practitioner has completed and has documented approval of 750 hours of successful mentorship during this provisional period, they may be granted full practice authority and continue prescribing necessary medications to the population within their scope without any mentorship or supervision (50).

Colorado also has a Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) to track the prescribing and dispensing of controlled substances to clients. Registration with the PDMP is required for clinicians with prescriptive authority and healthcare providers must check this database prior to dispensing controlled substances to clients (50).

Additionally, continuing education in the form of two contact hours of education related to the prescribing and monitoring of controlled substances is required every two years when APRNs renew their Colorado state licensure (50).

Healthcare providers in Colorado must remain up to date with both federal and state regulations to ensure safe prescribing practices, compliance, and ensure patient and colleague communication regarding controlled substances such as narcotics (50). Regular review is key.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- For patients with both chronic pain and substance use disorder, how can you collaborate with the interdisciplinary medical team to provide comprehensive care?

- How can you help a patient with SUD with re-occurring and chronic pain?

- How can the integration of complementary and alternative therapies enhance the effectiveness of pain management for patients with substance use disorders?

- How might the use of the Colorado Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) help in preventing opioid misuse?

- How can clinicians still ensure clients receive appropriate pain management while being monitored in the PDMP?

Incidence And Prevalence of Substance Use Disorders

By conducting a careful pain assessment, nurses can gain an understanding of a patient’s subjective pain perceptions as well as its severity, causes, and symptoms. Nurses may implement both non-pharmacologic and pharmaceutical interventions to manage pain appropriately.

The role of the nurse practitioner is to formally diagnose and order treatment, so a thorough understanding of pain management and identification of addiction risk factors is crucial. For DEA-registered practitioners, care should be given when choosing which pharmacological interventions to utilize, to minimize risks for substance abuse disorders and achieve maximum pain relief.

Uncontrolled pain or the development of substance use disorders can disrupt functional living and complicate comorbidities. Collaboration among members of the health care team and patients themselves is also key, including setting realistic goals for managing pain effectively and actively participating in their plan of care.

Pain, including abdominal, head, throat, and back pain, continues to be the top four most common patient complaints seen in primary care (1). Data from the CDC indicates that in 2021, nearly 20% of U.S. adults experienced some form of chronic pain. Quality of life can be significantly impacted by chronic pain, both through impaired function and also through loss of income by reduced or lost ability to work. It is estimated that the United States spends nearly $300 billion annually on evaluating and treating chronic pain (53).

Certain demographics are more at risk of experiencing chronic pain as well. Populations disproportionately affected by chronic pain include:

- Adults over 65

- Women

- American Indian or Alaskan Native race

- People living in poverty

- Under or un-insured individuals

- Those living in rural locations

Comorbid health conditions and disabilities also increase the risk of chronic pain conditions (53).

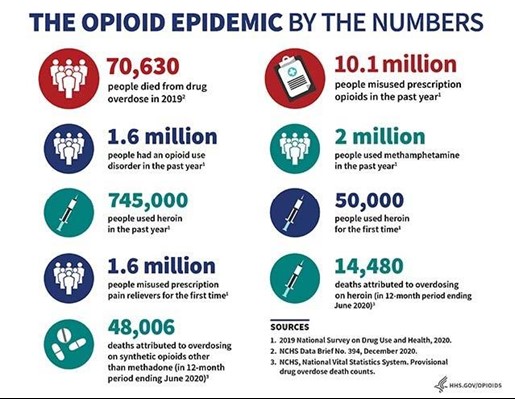

Unfortunately, a result of prescribed pain medications is the possibility of substance use disorders, which is a continued important issue in the United States. The opioid epidemic continues to be a serious public health concern. From 1999 to 2022, the number of opioid related deaths increased 10-fold. In 2022, 108,000 people died from drug overdoses, 76% of which were related to opioids.

Assessing, diagnosing, treating pain, and identifying risk factors for substance use disorder are important topics for every nurse practitioner and the appropriate management of pain disorders can help prevent these deaths.

When considering risk of opioid misuse, some, though not all, demographics are similar to those most likely to be affected by chronic pain. Anyone can be affected by opioid misuse, however risk factors for opioid misuse include (54):

- Males

- Younger age

- American Indian or Alaskan Native

- People with some college education

- Veterans

- Past or current abuse of other substances

The most common substance use disorders in the United States are (2):

- Alcohol use disorder (29.5 million)

- Cannabis use disorder (16.3 million)

- Methamphetamine use disorder (1.6 million)

- Opioid Use disorder (5.0 million)

- Tobacco use disorder (16 million)

It is estimated that the cost of emergency room and inpatient services for substance use related conditions exceeds $13 billion annually in the United States. This does not account for outpatient treatment, lost productivity for those affected, or legal costs (55).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What is your role in helping combat the opioid epidemic and growing prevalence of substance use disorder in the U.S.?

- What are causative factors for the most common pain conditions?

- What is your role in identifying and treating the most common substance use disorders in your practice?

- What steps can healthcare facilities take to ensure that high risk populations are being identified when receiving pain management care?

- How can nurses and nurse practitioners adjust their care strategies to address the needs of populations at risk for substance use disorders?

Types of Pain

Pain can be an ordinary response to illness or injury and doesn’t typically require medical intervention. Pain may be divided into various categories depending on its onset and duration, including acute, chronic, or breakthrough (3). An understanding of the broad categories of pain, as well as the conditions that cause them and their treatments, is necessary to guide clinicians when caring for these clients, keeping substance misuse disorders in mind.

Acute pain is experienced from within minutes of an injury up to several months afterwards. It is typically related to illness, damage to tissue, or even surgery. Common causes include cuts, burns, fractures, strep throat, UTIs, childbirth, toothaches or gum infections, surgery. Acute pain usually resolves when the underlying cause has resolved through treatment or natural healing. Management of acute pain can include NSAIDs, acetaminophen, short term use of opioids, and local anesthetics. Head, ice, rest, and physical therapy are non pharmacological methods that can also be used to manage acute pain. Careful prescribing of opioids for acute pain includes not providing more than is reasonably needed for the extent and duration of the pain.

Chronic pain is experienced beyond six months and usually due to a continuous medical issue or condition. Many times, chronic pain is linked to nerve damage, inflammation, or degeneration of bone or tissue. Chronic pain can cause significant impact on daily functioning and lead to mental health problems like depression and anxiety. Common conditions that lead to chronic pain include osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, strain of back muscles, degenerative disc disease, migraines, fibromyalgia, and tumors. Treatment for chronic pain can include NSAIDs and acetaminophen, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, opioids, and topical analgesics. Non pharmacologic methods include cognitive behavior therapy to help with coping, physical therapy, acupuncture, massage, deep breathing and meditation exercises. Opioids for chronic pain must be closely monitored and reevaluated frequently.

Neuropathic pain occurs as a result of damage or dysfunction of the nervous system. It can feel like stabbing, burning, or electric shock. Common conditions that cause neuropathic pain include diabetes, trauma to nerves, shingles, spinal cord injury, and multiple sclerosis. Neuropathic pain does not typically respond to NSAIDs or acetaminophen like other types of pain would, so treatment more commonly includes anticonvulsants, antidepressants, topicals (like capsaicin cream), and sometimes opioids. Physical therapy, psychotherapy for coping, and a transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulator are possible complementary techniques that may provide some relief.

Nociceptive pain occurs when tissues are damaged and is often described as sharp, aching, or burning. It commonly occurs with sprains, contusions, fractures, incisions, tendinitis, bursitis, or tumors. Nociceptive pain can be treated with NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and opioids. The use of head, cold, and physical therapy can also be useful.

Radicular pain occurs when a spinal root nerve is inflamed or being compressed and causes radiating pain to specific areas depending on where the injury is located. Herniated discs, spinal stenosis, sciatica, or spinal tumors can all cause radicular pain. Treatments for this type of pain include NSAIDs, muscle relaxants, or epidural steroid injections to try and reduce inflammation and associated muscle spasms. Physical therapy, spinal decompression, and even surgery to relieve nerve compression can also be utilized.

Another, though less common, type of pain is phantom pain which is a type of neuropathic pain. Phantom pain is the sensation of pain perceived in a limb that has been amputated. It is believed to be related to nerve memory and reorganization of the central nervous system after amputation. It can be difficult to treat but may include use of antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and opioids. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, cognitive behavior therapy, and mirror therapy can be used as non-pharmacological methods of pain management

Breakthrough pain occurs when pain that was controlled with medication begins to be felt beyond the pharmacological properties of the pain medication (35).

| Type of Pain | Definition |

| Acute | Short-term from minutes to less than 6 months |

| Chronic | Continues beyond 6 months |

| Neuropathic | Damage to nerves felt as sharp, stabbing, burning. |

| Nociceptive | Damage to body tissues felt as sharp, achy, or burning. |

| Radicular | Damage from a compressed or inflamed spinal nerve, felt as constant and steady pain. |

| Phantom Pain (a type of neuropathic pain) | Sensation of pain from a limb/digit that has been amputated. Nerve endings have memory. |

Table 1. Types of Pain

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What are resources you can offer your patient about options for pain management?

- What questions should you ask your patient to identify the type of pain they are experiencing?

- How can you identify the type and source of pain your patient is experiencing?

- How might the type of pain being experienced impact that treatment pharmacologic and non pharmacologic treatment modalities that are most effective?

- Which factors related to pain type should be considered to minimize the risk of dependency or misuse when prescribing opioids?

Pain Assessment

Pain is considered the fifth vital sign and provides significant information about a patient’s lived experience.

In 1995, it was proposed by a practicing physician James Campbell that pain should be considered the fifth vital sign, which was later supported by the American Pain Society as a standard practice guideline (6). In addition to blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, and pulse oximetry, a pain assessment provides information necessary for holistic care.

A regular pain assessment allows nurses to manage patient discomfort more effectively by creating personalized plans of action to effectively address pain management needs. Prior to ordering or administering pain medications, nurses must perform an in-depth pain evaluation that includes gathering data from various sources, including the patient’s medical history, chief complaint, and a physical exam. A follow-up is important to evaluate any therapeutic results of prescribed medication.

Components of a Pain Assessment

A systematic pain assessment is key to correctly identifying all the components of pain (7).

- Assess risks for pain. For example, advanced age, cancer, anxiety, recent surgery/invasive procedures increase the likelihood of experiencing pain and discomfort.

- Assess pain using an approved pain scale to create a baseline for the current pain level (which will be discussed later). Remember pain is subjective and influenced by age, gender, and cultural factors.

- Identifying the pain source such as nociceptive, neuropathic, referred, somatic, visceral, or phantom pain.

- Assess the type of pain (acute or chronic) and contributory factors.

- Evaluate their past response to pharmacological interventions and analgesics, including any adverse reactions they experience.

- The assessment should include physical, behavioral, and emotional signs of pain including confusion, diaphoresis, moaning, decreased activity levels, irritability, guarding, clenched teeth, muscle tension, depression, insomnia, confusion, diaphoresis, moaning, and grimacing.

Pain Assessment Mnemonics

Nurses often use three mnemonics to remember standardized questions for conducting a comprehensive pain assessment:

- COLDSPA

- OLDCARTES

- PQRSTU

Each letter presents important questions to ask the patient about their pain.

Nurses may ask any number of questions to obtain information for each category. Examples of each of these mnemonics can help the practitioner remember to ask important questions relevant to pain.

| COLDSPA | Questions to ask: |

|

C: Character |

What does the pain feel like? Does it feel like burning, stabbing, aching, dull, throbbing, etc.? |

|

O: Onset |

When did the pain start? What were you doing when the pain started? |

|

L: Location |

Where do you feel the pain? Does it move around or radiate elsewhere? Can you point to where it hurts? |

|

D: Duration |

How long has the pain lasted? Is the pain constant or does it come and go? If the pain is intermittent, when does it occur? |

|

S: Severity |

How would you rate your pain on a scale of 0 to 10, with “0” being no pain and “10” being the worst pain you’ve ever experienced? How much does it bother you? |

|

P: Pattern |

What makes your pain feel better? What makes your pain worse? Does the pain increase with movement, certain positions, activity, or eating? |

|

A: Associated Factors |

What do you think is causing the pain? What other symptoms occur with the pain? How does the pain affect you? |

The “OLDCARTES” mnemonic consists of the letter of each category of questions to ask.

- O: Onset

- L: Location

- D: Duration

- C: Characteristics

- A: Aggravating factors

- R: Radiating

- T: Treatment

- E: Effect

- S: Severity

The “PQRSTU” mnemonic also helps the clinician to ask about components of pain.

- P: Provocative/Palliative

- Q: Quality/Quantity

- R: Region/Radiation

- S: Severity

- T: Timing/Treatment

- U: Understanding

Regardless of the pain assessment framework utilized, it is critical that open-ended questions allow patients to describe the pain in their own words. Closed-ended questions result in either yes/no responses or fail to capture an accurate account of the patient’s pain.

It is also vitally important for the nurse to follow-up on initial responses by asking clarifying questions so they can create and implement an individualized pain treatment plan to address all aspects of pain. In completing a pain assessment with patients, the nurse practitioner gains better trust with the patient, which can result in better patient adherence to prescribed treatment.

Pain is Subjective

Given that everyone responds differently, each person’s experience of pain will vary widely, even for stimuli with similar properties. For instance, some may feel considerable discomfort after receiving injections while others experience none, which means consequently we must treat pain according to whatever the individual claims it to be.

Due to this completely subjective nature of describing pain, the evaluation of the response to pain medication is also subjective. Clinicians must recognize the biological, psychological, and social factors that affect the perception of pain as shown in the following table.

| Biological Factors | Psychological Factors | Social Factors |

|

|

|

Table 2. The biological, psychological, and social influences on pain. (47)

Pain Scales

At the core of any pain assessment is determining the intensity. As pain cannot be objectively tested to pinpoint an individual’s sensations, providers use pain scales as tools for objectively understanding each patient’s discomfort and setting realistic pain goals. Nurses have access to numerous standardized pain scales.

A popular one is numerical, in which patients rate their discomfort between zero and 10, with zero being no pain and 10 being the worst pain ever experienced. While simple and user-friendly, numerical pain scales cannot be used by children or other populations who cannot accurately quantify pain, therefore alternative pain scales such as FACES scale, FLACC scale comfort behavioral scale or PAINAD scale may be used.

The FACES scale is a visual assessment tool for children and other people who cannot use numeric scales. When using it with children or others who cannot describe numbers accurately, explain to the patient that each face represents either no pain, some discomfort, or intense distress. For instance: Face 0 doesn’t hurt at all while Faces 2-6 hurts just slightly more, while Face 8 hurts even further before reaching 10, which represents extreme suffering. Ask the individual which of those depictions best represents their discomfort.

Figure 1. Wong Baker FACES Scale used to help score pain level.

The FLACC scale is used to assess pain in children aged two months to seven years and those unable to verbalize. It comprises five criteria such as face, legs, activity, cry, and consolability. Care providers assign each criteria a score between zero and two upon observation of their patient and then combine all five scores together into an overall pain score between zero (no pain) and 10 (10 severe) (8).

The Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) Scale is used to assess pain in patients with advanced dementia (9). This scale has five criteria including breathing independent of vocalization, negative vocalization, facial expression, body language, and consolability.

Like the FLACC scale, each of the five criteria are assigned a score of 0, 1, or 2. The provider observes the patient, assigns a score for each criterion, and adds the scores. The total pain score will be between 0 and 10, with 0 being no pain and 10 being severe pain. Like FLACC, the PAINAD scale is simple, valid, and reliable, but it may not always result in the most accurate pain assessment, as it requires the nurse to calculate the score based upon observed patient behaviors rather than the patient’s subjective pain rating.

Online Resources:

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How does culture affect a patient’s expression of pain?

- What pain scales do you commonly use in assessing pain and are they appropriate for the age, gender, and verbal skills of the patient?

- What other questions should you ask about a patient’s tolerance of pain and how they have handled pain in the past?

- In what ways can the nurse ensure pain assessments are both subjective and objective indicators of pain in order to comprehensively understand the client’s discomfort?

- How can follow up evaluations after clients have received pain management impact the quality of care and affect rapport or trust in the healthcare system?

- What factors must be considered when selecting an appropriate pain scale for a client’s unique case?

Cultural Influence on Pain

Culture plays an intricate role in how individuals express physical and emotional discomfort. There are certain thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors surrounding pain that may vary by culture or have certain similarities within a particular culture. While each client is an individual, awareness of cultural influence on the acknowledgment and expression of pain can help clinicians when evaluating and addressing pain in a culturally sensitive way. Common cultural attitudes about pain include (10, 56):

- East Asian: Values stoicism and emotional control. Clients may underreport pain or not show distress due to cultural expectations of endurance and dignity. Will typically accept pain medication as well as traditional medicines.

- Middle Eastern: May openly express discomfort verbally. Have an expectation of active response from healthcare. Will accept pain medication.

- Hispanic: Pain is emotionally distressing. May express more through nonverbal cues. Rely on strong family involvement. May wish to combine pharmacological management with traditional remedies or non pharmacological methods.

- Western culture: Varies widely based on region or other cultural factors, but in general pain is expressed in varying forms and there is an expectation of healthcare to address it in whatever means available.

- African American: May downplay the severity of pain or avoid seeking healthcare. Expresses primarily through nonverbal cues. May avoid or refuse pain medication for fear of addiction.

Although culture may impact pain levels differently for each patient, nurses must understand its impact before creating an individual plan that best meets each person’s specific needs.

Special Populations

Additional considerations must be given to special populations, such as the very young, very old, clients with language barriers, or disabilities.

Children have limited vocabulary or their developmental level may limit their ability to indicate or qualify their pain. Effective assessment of pain in children requires age appropriate assessment tools such as the FLACC scale for younger or nonverbal children, or the Wong-Baker FACES scale for older children. Physiologic signs of pain can also be observed, including tachycardia, crying, guarded movements, etc. Parents or guardians should also be included in the assessment process.

It can also be challenging to assess pain in the elderly or older adults who may have cognitive impairment or reduced communication abilities. Observational tools such as the PAINAD scale can be useful, as well as behavioral indicators like facial grimacing, restlessness, or being withdrawn. Pain should not be discounted as a normal part of aging in this group and assessment of co-occuring conditions like arthritis is necessary.

Clients with limited English proficiency may also have difficulty accurately conveying their pain to healthcare professionals. Language barriers require interpreters or visual aids as well as assessment of nonverbal cues like posture, facial expression, and gestures. For clients of another culture, they may also have different expectations about pain and how it is addressed. Culturally sensitive care should be utilized to avoid making assumptions about a client’s pain based when they cannot verbally convey it.

Disabled clients may have difficulty expressing pain, particularly if their disability impacts their communication abilities. Deaf or mute clients will have limited ability to communicate verbally and may require the use of sign language or written communication tools. Visual assessment and nonverbal cues are also useful. Clients with physical disabilities should also not be assumed to also have cognitive abilities and their communication about pain should never be discounted (56, 57).

Biases in Pain Assessment

It is also important to acknowledge potential biases in healthcare that may impact assessment of pain. Individual clinicians need to examine their own personal biases, and there are many assumptions or beliefs that may be perpetuated by healthcare as a system and also need to be addressed. Common biases related to pain include (57):

- Gender: Women are often perceived as being dramatic or emotional and their pain may be minimized or attributed to psychological origins. Men may feel they need to be stoic and may under report pain.

- Age: As discussed previously, elderly clients may have their pain minimized or attributed to “normal aging.” Children may be dismissed as exaggerating.

- Race: Evidence shows that Black and Hispanic clients are less likely to have their pain taken seriously and receive adequate pain management.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What strategies can be used to overcome language barriers when assessing pain in certain populations?

- In what ways can healthcare professionals ensure cultural influences are considered when assessing pain, while avoiding stereotyping or making assumptions?

- In what ways can clinicians address implicit biases to improve the accuracy and effectiveness of pain assessments?

- What interventions or policies can healthcare institutions implement to address disparities in pain management among racial and ethnic groups?

Case Study

Scenario:

Jimena Cortez, a 72 year old Hispanic woman, presents to the primary care office with complaints of lower back pain. This pain started off and on around 8 months ago, but has been worsening and becoming more consistent in the last 3-4 months. She uses the Wong-Baker FACES scale to quantify her pain as a 7/10 most days. Standing or walking for long periods exacerbates the pain. The pain is limiting her ability to perform daily functions which is frustrating to her.

She also has a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and osteoarthritis. She speaks limited English and her daughter typically accompanies her for translation.

Assessment:

The nurse practitioner seeing Mrs. Cortez performs a comprehensive pain assessment using the COLDSPA mnemonic.

- C (Character): the pain is described as “aching and burning” in her lower back, sometimes radiating to her left leg

- O (Onset): the pain began around 8 months ago and has gradually worsened in frequency and intensity

- L (Location): Primarily lower back, occasional pain radiating to the left leg

- D (Duration): Used to be off and on, now is constant and worsens with activity

- S (Severity): Rated as a 7/10 at rest and a 9/10 after prolonged standing

- P (Pattern): Alleviated by sitting or lying down (rest) but worsened by walking, bending, standing

- A (Associated factors): Reduced mobility, functional limitations, frustration

Management Plan:

To start, Mrs. Cortez is diagnosed with chronic pain with some radicular pain. She is advised to use acetaminophen for pain relief, as well as given a prescription for gabapentin for the neuropathic radiation. She is also referred to physical therapy to strengthen core muscles and improve mobility.

After 3 weeks, she follows up and reports minimal to no relief with the physical therapy and gabapentin. In collaboration with the physician, Mrs. Cortez is started on a trial of low-dose opioids, adhering to Colorado’s Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) requirements. Referral to a pain specialist is also initiated. She is also referred to a counselor to help with coping with changes in mobility and function.

Challenges:

This case demonstrates the complexities of assessing and managing pain in special populations, including older adults, limited English proficiency, and clients with chronic conditions. The use of culturally sensitive care, appropriate pain assessment tools, and acknowledgement of potential biases is necessary for optimum outcomes. The following considerations were given to Mrs. Cortez’s case:

- Language barrier

- Utilizing the Wong-Baker FACES Scale to assess her pain is an appropriate method for someone with limited English proficiency and ensures that Mrs. Cortez can accurately quantify her pain experience.

- Her daughter can help with translation, but an interpreter provided by the facility would be preferred as this would eliminate inconsistencies or personal influences in translation and also ensure a translator is always present without Mrs. Cortez needing to arrange for it.

- Cultural sensitivity:

- Mrs. Cortez’s Hispanic background may impact her expression of pain and her expectations for treatment; she may find pain to be emotionally distressing and expresses it openly in an attempt to receive help.

- Family involvement is desirable in addressing this issue and clinicians should communicate openly with the client and present family members.

- Age

- Chronic pain in older adults may be underreported or misattributed to “normal aging,” particularly for clients with existing comorbid conditions.

- Using nonverbal indicators for pain to corroborate the client’s reports of pain is useful, as well as investigating further with assessment and diagnostics.

- Gender

- Women’s pain is often underreported or underestimated in healthcare settings

- Clinicians need to believe client reports of pain and not undermine them or assume they are exaggerating.

Outcomes Evaluation:

By utlizing evidence-based, culturally sensitive approaches, the nurse practitioner ensured equitable, client-centered care. A systematic, multimodal approach to pain assessment and management allowed the healthcare provider to deliver holistic, compassionate care tailored to Mrs. Cortez’s unique needs. This approach not only improved her quality of life but also strengthened her trust in the healthcare system

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What additional steps could the nurse take if Mrs. Cortez’s pain persists despite the current plan?

- In what ways does involvement of a multidisciplinary team improve the outcomes for this client?

- How did the healthcare team ensure the pain management strategies for Mrs. Cortez were culturally sensitive and adjusted for her unique needs?

- In what ways could things have been improved upon?

Reassessment After Intervention

Pain must always be assessed again following implementation of an intervention to determine its effectiveness in relieving symptoms. Oral medications should be assessed within 1 hour while intravenous treatments within 15-30 minutes, and per facility protocol (39).

For a primary care provider in an office clinic, reassessing pain should use the same pain scale used during initial assessment at the next visit. If their discomfort has not decreased to meet their established goal level, further interventions will be needed.

Interventions may involve medications and/or non-pharmacological modalities like heat, ice, music therapy and repositioning to achieve the patient’s ideal pain goal (40). Intervention and reassessments must continue until this goal has been attained. All reassessments and interventions must be documented in their medical record.

Pain Management Care Plan

In developing care plans for pain, nurse practitioners should provide a tailored approach to address each patient’s unique pain management needs. Beginning with an in-depth evaluation, the nurse practitioner gathers information regarding medical history, current pain symptoms, functional status, psychosocial factors, and desired goals for treatment.

Based on their evaluation, nurse practitioners collaborate with patients to set realistic expectations and goals for pain management care plans that integrate pharmaceutical interventions along with nonpharmacological interventions.

Pharmacological interventions include using analgesic medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids and any adjuvant medicines such as antidepressants or anticonvulsants as well as topical agents to relieve discomfort (41).

Nurse practitioners carefully consider all risks and benefits when prescribing medications to their patients, tailoring individualized plans to optimize pain relief while mitigating adverse side effects as well as risks related to opioid misuse or addiction.

Non-pharmacological interventions also play a vital part in pain management. These may include (58):

- Physical therapy: This involves exercises and manual techniques that improve strength, posture, and mobility. This modality is particularly useful for conditions like osteoarthritis or radicular pain.

- Occupational therapy: Focuses on improving daily functioning through ergonomic techniques, use of assistive devices, and energy conservation. These techniques can help clients maintain independence and improve quality of life.

- Acupuncture: This traditional Chinese therapy involves needles inserted to specific nerve pathway points on the body and may provide pain relief through release of endorphins.

- Massage therapy: This method involves manipulation of soft tissue to relieve muscle tension and improve circulation, which can reduce stress and promote pain relief. Massage can also address secondary effects of chronic pain such as poor sleep.

- Relaxation techniques: Techniques like deep breathing, guided imagery, and progressive muscle relaxation activate the parasympathetic nervous system and can provide a sense of calm and help with coping with pain.

- Meditation: Mindfulness practices, meditation, and yoga can reduce pain intensity and promote relaxation. These techniques can be useful for chronic conditions like fibromyalgia or low back pain.

- Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT): This is a type of that teaches coping and reframing strategies that can reduce the emotional burden of pain. This is particularly useful for clients who are also experiencing anxiety or depression in response to chronic pain or loss of functionality.

Nurse practitioners work collaboratively with other healthcare professionals such as physical therapists, psychologists, and pain specialists to coordinate and integrate interventions into a patient’s care plan. Education and self-management strategies also play a pivotal role in pain management plans. Nurse practitioners provide patients with education about their pain condition, its causes, and possible solutions.

Patients can become actively engaged in their care by learning self-management techniques such as pacing activities, maintaining proper posture, using heat or cold therapy, and practicing stress reduction methods.

Additionally, patients receive guidance regarding medication adherence, potential side effects and the significance of regular follow up appointments to monitor progress. Furthermore, their pain management care plan incorporates strategies designed to address any psychosocial factors which might impact pain for an improved experience and treatment outcome. Screening may include depression, anxiety, sleep disturbances, substance use disorders and any additional coexisting conditions.

Referrals may be made to mental health professionals, social workers, or support groups as a source of additional assistance and resources for the patient. Reassessment and monitoring should form integral parts of any pain management care plan. Nurse practitioners collaborate closely with patients to monitor pain levels, functional status, effectiveness of medication treatment plans, and any adverse side effects. Treatment plans may be altered accordingly as needed based on response to therapy, changes to condition, or evolving goals of care.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How do you educate your patient about pain management options?

- How do you educate your patient about safe prescription medications?

- What resources do you have to create a nursing care plan for pain?

- In what ways do you think the type of pain impacts the effectiveness of various non pharmacological pain control methods?

- How might you assess and address potential psychosocial implications (like anxiety and depression) when creating a unique pain assessment and treatment plan?

Pharmacological Pain Management

Pain medications are divided into two main groups, including analgesics and adjuvants. Analgesics are used to prevent or treat pain and can further be classified as opioids or nonopioids; the classification is based on whether their original source is from poppy plants, known as opioids (41).

Nonopioids include medications not classified as opioids while adjuvants contain medication with both independent analgesic properties as well as additive properties when taken together with opioids.

When taking analgesics, it is wise to start with those having minimal side effects in a smaller dose and using minimally invasive approaches.

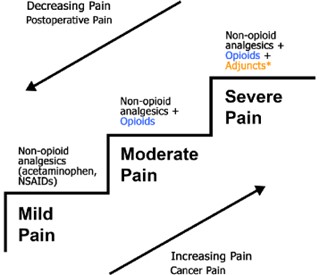

Developed by the World Health Organization, Figure 2 (below) demonstrates the stair-step ladder approach to guide the advancement of pain

Originally created to assist cancer patients, the pain ladder model can now be applied to all forms of discomfort. Nonopioids should generally be employed first in managing pain and if persistent or increasing discomfort continues then opioids or adjunct therapies should be added alongside nonopioids as appropriate (42).

For severe, short-term pain that’s expected to diminish gradually over time however, opioids, nonopioids and adjunct therapies might initially all be given before gradually withdrawing their presence so only nonopioids remain.

Figure 2. The WHO pain ladder is a guide for using pain medications responsibly (51)

Analgesic Medications

Analgesic medications (nonopioids and opioids) are used to alleviate or manage pain. Nonopioids tend to work best at managing mild-to-moderate discomfort in most cases and are well tolerated by most users. Examples of such analgesics include acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS).

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen is a non-narcotic analgesic and fever reducer. It is available by prescription or over the counter (OTC). Acetaminophen (the active ingredient found in Tylenol) can help relieve mild pain in all age groups and is generally safe. As it can be administered orally, sublingually, or intravenously, it could also provide an ideal choice for people unable to take oral medications.

The pharmacokinetics and mechanism of action of acetaminophen include the quick absorption from the gastrointestinal tract within 30-60 minutes. Delays of absorption to peak concentration in the circulatory system can be due to food in the stomach. It is then metabolized by the liver via the three main hepatic pathways including glucuronidation, sulfation, and CYP450 oxidation (44). The half-life is approximately 4 hours, however with hepatic injury or overdose the blood peak level can be accelerated to 2 hours.

In patients suffering from liver failure, it should be used with caution as one potential adverse side effect could be hepatotoxicity. Therefore, it is crucial that daily dosage be closely monitored (12). Millions of people use over the counter (OTC) pain relievers every day to treat minor aches and pains.

Usually, these medicines are safe and effective, but they can be dangerous and even deadly when they are not taken as directed (11). Acetaminophen, also called paracetamol in many other countries, is sold by many names including Tylenol, Panadol, Ofirmev, Acephn, and Mapap.

It is used effectively for fever, muscle pain, neck pain, plantar fasciitis, sciatica, and common body aches and pains. It is abbreviated as APAP for acetyl-para-aminophenol, which is the chemical name and is known by 28 band names in the United States (12).

It is very commonly used in combination drugs for pain as a nonnarcotic analgesic and known as Excedrin, Goody’s Body Pain, Saleto, Exaprin, Levacet, Painaid, Apadaz, Rhinocaps, Staflex, and included in over-the-counter medications for acute cold symptoms, respiratory conditions, and headaches (42)

In addition, it is a component of some narcotic prescriptions. Acetaminophen can be used as a sole medication or as an active ingredient in many OTC and prescription medicines. Acetaminophen is generally safe at recommended doses, but if taken in larger dosages or frequency, it can cause serious and even fatal liver damage. In fact, acetaminophen poisoning is a leading cause of liver failure in this country (13).

Safety guidelines include:

- Older adults: limit to no more than 3,200 mg in 24 hours.

- Healthy young adults: can take no more than 4,000 mg.

- Alcoholism: should limit themselves to no more than 2,000 mg daily.

Add all sources of acetaminophen into daily totals, including amounts found in combination medicines such as Percocet 5/325, which contains 5mg Oxycodone and 325 mg Acetaminophen. One Percocet 325 mg tablet should count toward the total daily acetaminophen dosage and should be included when prescribing individual dosages to avoid too close an administration of multiple medicines at once.

As an illustration, if 500 mg of acetaminophen is prescribed every four hours to combat fever while 5/325 Percocet is intended as pain reliever, both medications should not be given together within four hours as it would increase intake significantly and cause too much acetaminophen.

NSAIDs

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) are nonprescription medicines prescribed to relieve mild to moderate discomfort and may also be combined with opioids for treating severe pain. The pharmacokinetics of NSAIDS is based on the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination of the drug as all oral medications. NSAIDS inhibit both COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes and play a role in prostaglandin mediated pain from inflammation (44).

Although they offer more gastrointestinal protection than aspirin, they do have cardio-nephrotoxic adverse effects. Due to the inhibition of prostaglandins and thromboxane, the desired actions are anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, and analgesic.

Common examples of NSAIDs are Ibuprofen, Naproxen and Ketorolac. Ibuprofen should be taken every 6-8 hours for adults aged six months or over. Naproxen can be taken 2-3 times per day and provides longer-acting pain relief than Ibuprofen does. Ketorolac may be taken temporarily (up to five days) in cases of moderate-to-severe adult pain relief. Aspirin is often the last line of nonopioids before turning to opioids and may help treat breakthrough pain for patients already taking opioids.

Side effects from taking an NSAID drug could include dyspepsia, nausea, and vomiting. To minimize risk, NSAIDs should always be taken with food. Long term or high dose use also increases risks such as heart attack, stroke, and heart failure; and must be prescribed carefully for people over 60 or those with liver or renal problems. One notable exception is aspirin, which when taken in low doses may reduce the risk of another heart attack in people who have already had one. NSAIDs may cause gastrointestinal bleeding when combined with warfarin or corticosteroids.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How do you educate parents of children you are prescribing NSAIDs for regarding safety?

- How do you teach them to safeguard against accidental ingestion by other children in the home?

- How do you carefully prescribe NSAIDS for someone with renal problems?

- What education might you need to provide for clients taking acetaminophen-containing medications to reduce the risk of accidental overdose?

Narcotic Pain Relief Categories

Opioid Agonists

- Codeine

- Fentanyl

- Heroin

- Hydrocodone (Lortab, Vicodin, Percocet)

- Hydromorphone and Oxymorphone

- Meperidine

- Morphine

- Oxycodone (OxyContin, Percodan)

Partial Opioid Agonists

- Buprenorphine (Subutex)

- Tramadol

Pure Opioid Antagonists

- Narcan

- Naltrexone

- Nalmefene

Opioids

Opioids include codeine, fentanyl, hydrocodone, meperidine, hydromorphone, methadone, morphine, oxycodone, and heroin. Drugs from the class of opioids are powerful analgesics and used for pain management. From 2000 to 2021, more than one million people in the United States died from opioid drug overdoses and over 80,000 died from opioids in 2021 (14).

Opioids are categorized as schedule 1 or 2 drugs by the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). A schedule 2 drug, such as morphine, means that although it has been approved for medical treatment as an analgesic, it has high potential for strong psychological and physiological dependence.

It has been used for over 100 years as an analgesic. Heroin is made by taking morphine, from the opium plant, and adding a chemical reagent that makes it more potent and potentially dangerous. Heroin is a schedule 1 drug and is not approved for any medical use as it is highly addictive.

So how did we get to this point of millions of Americans using and abusing opioids? The documented use of opioids began as early as the 3400 BC in Mesopotamia, which they called the “joy plant.” Opium was used for every medical malady from diarrhea, cholera, rheumatism, fatigue and even diabetes by early Egyptians.

Opium was then regularly traded by Turkish and Arab traders in the 6th century. Opioid use became much more available in the early 1700s as the British refined the production from the Asian poppy plant grown in the British province of India and sold in China. What became helpful as analgesia quickly became popular for treating every malady and even used as entertainment in historical records of opium parties (15). British ships filled 1,000 chests of opium into China in the 1760s and ships gradually increased it to 4,000 chests in 1800 to eventually 40,000 chests in 1838. Opium was so popular in China and the desire for porcelain, silk and tea was equally in demand in the West, so the trading continued.

Because of its powerful addicting properties to the Chinese citizens, the Chinese emperor Yongzheng (1722-1735) eventually prohibited the sale and smoking of opium, which resulted in two infamous Opium Wars. Opium trading eventually became more regulated and slowed during the communist reign in China. Unfortunately, the opium trading continued with new players such as tropical growers and illegal importers from Central and South America to the United States.

In the late 1800’s Bayer created heroin and misuse was rampant causing regulations and taxes to thwart its use (15). Then after WWII and Vietnam another wave of use and abuse crossed America with the resultant reflex to regulate and tax its use. The war on drugs has continued.

Opioids are prescribed to manage moderate to severe pain by blocking the neurotransmitter that sends pain signals. Opioids can be administered via oral, intramuscular, intravenous, subcutaneous rectal or transdermal means. Oral opioids such as codeine, hydrocodone and oxycodone are typically prescribed to manage moderate pain.

Stronger opioids like fentanyl hydromorphone or morphine may be utilized if necessary for more intense discomfort. Morphine is often prescribed for cancer and end-of-life pain treatment because its impact does not reach a plateau point where increasing dosage won’t have any more of an impact.

Opioid Drugs include:

Natural Opioids:

- Morphine

- Codeine (Only Available in Generic Form)

- Thebaine

Semi-Synthetic

- Hydrocodone (Hysingla Er, Zohydro Er)

- Hydrocodone/Acetaminophen (Lorcet, Lortab, Norco, Vicodin)

- Hydromorphone (Dilaudid, Exalgo)

- Oxycodone (Oxycontin)

- Heroin

Fully Synthetic/Manmade

- Fentanyl (Actiq, Duragesic, Fentora)

- Meperidine (Demerol)

- Methadone (Dolophine, Methadose)

- Tramadol

- Levorphanol

- Pethidine

- Dextropropoxyphene

Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Opioids

Analgesics are a drug class that helps relieve the body from the sensation of pain by blocking chemicals in the neurons throughout the brain that sense pain. Neurons send messages of stimuli from the body to the brain and include different types of neurons that sense different things in the body from temperature, pressure, and even blood acidity and alkalinity.

The metabolism of opioids occurs through the Cytochrome (CYP-450 enzymes), which blocks the nerves from relaying messages to the brain (45).

Nociceptors, the nerve receptors for pain, send messages from noxious stimuli to the brain from the skin, walls of organs, and deep within the body such as muscles that something is hurting the tissues. Nociceptors send messages such as pressure, sharp objects, noxious smells, tastes and pain and the brain interprets those for immediate response to protect the body.

There are several neurotransmitters involved in pain signals, but the main ones are glutamine and substance P. When noxious stimuli trigger the primary neuron through the skin or muscle, the message is relayed by a secondary neuron to the spinal cord’s dorsal root ganglion towards the brain for interpretation.

These chemicals are relayed to the thalamus in the brain and then onto the limbic system for an emotional response. Ideally the message to the limbic area of the brain promotes learning to avoid the cause of the noxious substance in the future. Opioids inhibit pain signals at multiple areas in this pathway.

Opioids affect the brain, spinal cord, and even the peripheral nervous system. Opioids work on both directions of messages in the nervous system including the ascending pathways in the spinal cord, which are inhibited and the descending pathways, which block inflammatory responses to noxious stimuli. In the brain, opioids cause sedation and decrease the emotional response to pain.

Heroin, like morphine, passes through the liver and then is released back into the blood where it passes the blood-brain barriers. Heroin is then converted to morphine where it connects with mu receptors, but only faster and heroin is three times more potent than morphine (18).

Opioid receptors are found on both the primary and secondary neurons and when an opioid binds to these receptors no other pain signals are sent up to the brain, making opioids very effective against pain. Naturally these endogenous analgesic receptors include human endorphins, which comes from the name endogenous morphine.

Our bodies have three receptors called mu, kappa and delta which can be activated by opioid agonists like morphine, hydrocodone, or heroin. When mu receptors are activated, dopamine, a natural brain chemical, is also increased, which is the brain’s chemical for pleasure. Pleasurable feelings are inherently worth repeating, which drives the user to repeat the drug use (18).

Short term sensations of opioids include the following:

- Warmth sensation through skin and body

- A feeling of heaviness in arms and legs

- Pain relief

- Dry mouth

- Itchiness

- Possible dry mouth

- Drowsiness

- Slow heart functioning.

- Slow breathing.

- Relaxation

- Sense of well being

Opioid agonists come with additional noxious side effects. When a kappa receptor is stimulated it can also produce hallucinations, anxiety, and restlessness. The Delta and mu receptors can cause respiratory depression because as the midbrain is stimulated it suppresses the body’s ability to detect carbon dioxide levels in the body, which is the main stimulus for breathing. Other negative side effects include constipation, sedation, nausea, dizziness, urinary retention, and tolerance.

Tolerance is the requirement of the body to need increased amounts of the drug to reach its desired effects, which is why opioids can become addictive as the person requires more of the drug to achieve the desired pain relief (18). The key ingredient in opium is morphine, which began to be produced formally by the pharmaceutical company Merck. It was also discovered that when administered by IV, morphine is three times more potent than when administered by other methods such as smoking or snorting.

Long term use of opioids has been shown to cause the deterioration of the brain’s white matter and include long term effects of insomnia, chronic constipation, sexual dysfunction, irregular menstrual cycles in women, kidney disease and physical damage as a result of the administration technique such as snorting, smoking or IV drug use.

Although cocaine and morphine both have effects on the neurotransmitter dopamine, they work in different ways. Whereas the opioids increasing dopamine stimulation, cocaine blocks the reuptake of existing dopamine and makes it last longer producing a longer state of pleasure. Both opioids and cocaine drugs influence the brain’s interpretation of the pleasure drive reinforcing the drive for repeated behavior to get the drug.

In addition to the short-term withdrawal symptoms, long term opioid use causes:

- Decreased ability in decision making.

- Decreased ability for self-reflection and discipline.

- Decreased ability to effectively respond to stress.

Opioids can be effective pain relievers yet can become highly addictive if used improperly. Of the potential adverse reactions associated with opioid use, respiratory depression is the most serious. Those taking opioids must monitor for decreased respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and heart rate after receiving them. Those taking opioids for the first time or receiving increased doses, taking concurrent benzodiazepine use such as alcohol consumption or other sedatives may experience a more significant respiratory depression.

Treating opioid-induced respiratory depression requires treatment with Naloxone, which binds the mu receptors that opioids act on. Naloxone comes in a variety of preparations, including nasal spray, auto-injectors, and injectables.

Online video resource on how to administer Naxolone: https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/overdose-epidemic/how-administer-naloxone

Image 1. Preparations of Naloxone (48) (52)

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- In patients with substance use disorder, how can healthcare providers navigate balancing effective pain relief with risks of opioid medications?

- In patients prescribed opioids for pain management, what primary risk factors should the prescriber consider regarding the development of substance use disorder?

- What should be included in patient education play for those individuals prescribed opioids for pain management?

- How can clinicians monitor signs of opioid tolerance for clients utilizing long-term opioid therapy?

- What types of client education is necessary to reduce the risk of respiratory depression in clients taking opioids?

- Why is a detailed medication reconciliation necessary for client safety, particularly for clients taking opioids?

The Pain of Opioids

The Center of Disease Control has declared the overuse and abuse of opioids an epidemic (14). Ninety-one (91) Americans die every day from an opioid overdose (14). The US consumes 99% of all the world’s hydrocodone, 80% of the world’s oxycodone, and 65% of the world’s hydromorphone prescription opiate supply. Some 25% of all workers’ compensation costs relate to opioids and $56 billion/year is spent on opioid abuse costs. Trends of opioid overdose related deaths have increased 5.5% annually from 6 deaths per 100,000 people in the U.S. in 1999 to 16.3 in 2015.

In adults aged 45-54 the death rate from drug overdose was the highest of all age populations showing a constant trend upward of 10% annual increase in abuse and deaths (16). Clearly, America has an opioid epidemic that is claiming lives and lifestyles. Additional statistics, not as easily identified but very real, include lost productive work hours and loss of meaningful lives, families, and marriages due to opioid abuse (17).

Patients taking opioids must also be monitored for less severe side effects, such as constipation, nausea and vomiting, urinary retention, and itching. Opioids slow peristalsis and increase reabsorption of fluid into the large intestines, thereby slowing the passing of stool and removing the fluid from the stool so that it becomes concrete-like. It is important for the nurse to assess bowel function and encourage fluid/fiber intake and ambulation throughout the course of opioid treatments.

The provider can prescribe a bowel management program that includes a stool softener (such as docusate) and a stimulant laxative (such as sennoside, bisacodyl, or milk of magnesia). Should nausea and vomiting occur, antiemetics (such as prochlorperazine or ondansetron) may be prescribed. Antihistamines (such as diphenhydramine) may be prescribed for subsequent itching; however, they may cause drowsiness and exacerbate the potential for opioid-induced respiratory depression.

Fentanyl

The Centers of Disease Control has estimated that over 20,000 Americans died from fentanyl overdose in 2016 and that rate continues to climb in America. Fentanyl production in China has surged with the high demand in America and it has been called the new nuclear narcotic in the Opium War Against America (19).

Names of Fentanyl

Prescription Street Names

- Abstral: China Girl or China Town

- Actiq: Dance Fever

- Duragesic: Friend

- Fentora: Goodfellas

- Instanyl: Great Bear

- Lazandal: He-Man

- Sublimaze: Jackpot, King Ivory, Murder 8, Tango and Cash, Per-a-Pop (berry flavored Fentanyl lozenge)

One danger of fentanyl use is when fentanyl is mixed in with street drugs such as heroin and the user is unaware of what they are receiving. The quantity of fentanyl in street products also varies widely and can become quickly fatal as doses exceed what would have been carefully prescribed. Illegal street use without guidance, monitoring and education have created the dangerous opioid epidemic. The fully synthetic drugs such as fentanyl are much more potent and have the higher potential for abuse and death (19).

As an analgesic, fentanyl is 100 more potent than morphine and 50 times more potent than heroin (20). Ohio forensic testing in 2017 revealed 99% of their narcotic overdose deaths were fentanyl related and often due to combinations of synthetic fentanyl products including 25 fentanyl analogs such as acryl fentanyl, nor fentanyl, and furanyl fentanyl.

The state also determined that males accounted for 64% of overdose deaths and 92% were white (21). Over half of the deaths in Ohio were in persons aged 25-44 years (22). Trends continue to rise and causes point to the increased prescriptions of opioids for chronic pain and the availability of these drugs in non-prescription form.

Route and Administration of Fentanyl

Opioids can be administered by FDA approval through the subcutaneous, intramuscular, and intravenous and oral routes but due to variations in first-pass liver metabolism there are variations of response by users. Non-prescription drug users often speed the delivery by nasal and intravenous administration.

The potency of fentanyl and carfentanil have been demonstrated by the rapid deleterious effects on police officers who have come in contact with the powder through their skin during drug investigations and raids. One police officer overdosed just by brushing power off his uniform with his hand (23).

Subcutaneous fentanyl is commonly used to address chronic local pain, such as in a transdermal fentanyl patch that has a slow-release action. When fentanyl is delivered through more rapid routes such as IV or intranasal, the response is much quicker and therefore potentially fatal.

Fentanyl is usually administered by injection or topical patch in the hospital setting. It may be prescribed through the intradermal route for chronic pain and is classically used for chronic lower back pain.

Contraindications

It should not be used by someone who is allergic to the drug, has any type of breathing problem, a history of head or brain injury, liver or kidney disease, slow heart rhythms, concomitant use of sedatives like Valium or if a MAO inhibitor has been used in the recent 14 days or the client is already taking another narcotic.

There are no adequate studies to confirm safety or danger in pregnancy or breastfeeding so providers must be notified, and careful clinical decision making must be considered to weigh benefits from any possible damage to infants and mothers as it is a Category C claiming risk cannot be ruled out (24).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How can healthcare providers effectively communicate the concerns about SUD with someone seeking help for chronic pain?

- What is the role of family members in supporting patients with chronic pain?

- How does chronic pain affect the risk of developing substance use disorder?

- How might public health initiatives address the increasing prevalence of fentanyl related overdose in the United States?

- In what ways can clinicians improve safety when prescribing and monitoring fentanyl use for clients with chronic pain?

Patient Education and Support

Online and face-to-face support groups are available to help with effective and appropriate use of fentanyl. Often the only information provided is about the serious opioid epidemic and potential risk for addiction and abuse, however when used properly and within the clear instructions given by a medical provider who is monitoring for adverse reactions, it can be a helpful option for people in very real chronic pain.

Using any medications as directed is important because the route has been chosen for a specific reason. Unfortunately, a dangerous practice of chewing on a transdermal patch can speed up the delivery of the drug and create addiction and possibly respiratory depression or death. Mental and physical dependence can still occur even at prescribed doses so patients must be carefully monitored.

Supporting patients in their quest for relief from pain and judgment is extremely important. In the national conversation about opioid abuse, patients who have a real need for chronic pain continue to suffer as physicians are attempting to prescribe less, and pharmacies are blocking repetitive refilling of narcotics.

The dialog for effective pain management and effective systems to prevent opioid abuse must continue in creative, non-judgmental, and respectful ways. Encouraging support groups who can speak freely about issues and concerns can be helpful. Not all people who use fentanyl are drug addicts and should not be treated as such.

The pain blocking effects of intradermal fentanyl often takes from 12-48 hours and often up to 72 hours and may require a breakthrough alternative to pain relief until the full effect is in action. Titrating carefully for pain relief is required based on individualized patient needs. Variations in the need for higher dosages depends on the location of a transdermal patch, the quantity of fat on the body area and dryness of the skin where it is applied.

All patients should be taught to avoid alcohol consumption if using fentanyl. Patients also need to be aware that the narcotic may remain in the blood stream for up to three days and can be in hair and urine. Drug testing for abuse or employer requirements is most commonly done on hair and urine.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How would you explain to a patient the difference between fentanyl and heroin?

- How would you educate teens about the common street names for fentanyl?

- What alternatives to fentanyl are there that you could use in your practice?

- What information should be included in client education to ensure proper and safe use of fentanyl?

Patient-Controlled Analgesia

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) allows a patient to self-administer opioid medications such as morphine, hydromorphone, and fentanyl without requiring a nurse to give each injection, by using an automatic pump programmed with their dosage amount and rate/volume settings (37). A locked computerized pump connects directly to their IV line where medication syringes can be safely locked inside ready for an infusion at scheduled rates/volume settings; its programming ensures medication infusion occurs at its intended rate/volume setting without exceeding prescribed amounts.

Doses of medication can be self-administered on an as-needed basis by pressing a button. Patients may give themselves doses according to an adjustable schedule that includes preset interval times and dose limits per hour, up to four in total per hour limit. If these criteria are fulfilled, the PCA button illuminates to alert patients that doses can be administered when needed. Even when not illuminated, pressing it still delivers medication.

PCAs may only be used for patients who are alert, oriented, and can independently press the button. Because small doses of opioids are administered frequently, it is important to monitor patients for oversedation and respiratory depression. To reduce the risk of these adverse events, the patient and all caregivers should understand that no one should press the PCA button except the patient. Nurses should also ensure that the PCA button is easily within the patient’s reach, as patients on PCAs are at a high risk for falling.

Given the potential risk associated with PCA medication errors, both incoming and outgoing nurses should independently double check to verify correct drug, concentration, and dose (loading dose, PCA demand dose, continuous dose), lockout interval and 4-hour limit settings of their pump settings (36). When providing bonuses or changing any settings or replacing medication syringes two nurses will always be needed to verify results accurately.

As part of their PCA treatment, it is vital that patients carefully monitor their vital signs to detect possible indicators of respiratory depression such as decreased respiratory rate, oxygen saturation levels or heart rate. Nurses must follow organizational protocols when administering PCA medications – usually including taking baseline vital signs prior to commencing administration, for an extended period post administration and then every two hours for its duration.

Co-Analgesic Medications

Co-analgesics, commonly referred to as adjuvants, are medications with analgesic properties; however, their primary purpose is not pain relief. For instance, antidepressants are usually taken for treating depression but may also help manage chronic pain symptoms, like sleep issues and muscle spasms. Anxiolytics may help relieve anxiety symptoms but could potentially also treat chronic pain-related anxiety as well as relax muscles. Anticonvulsants used for seizures also block pain receptors and help with providing relief from certain forms of neuropathic pain while corticosteroids reduce inflammation while simultaneously managing this kind of discomfort from injured nerves.

Patient Education

Prescribers have an obligation to educate patients appropriately on pharmacological pain interventions in a culturally and linguistically sensitive manner. Drug education should help the patient comprehend the treatment plan, improve adherence to the treatment plan, alleviate fears while setting realistic expectations and discussing concerns openly, all to ultimately contribute to improved health, well-being, and patient outcomes.

Education should start when treatment commences and continue throughout the duration of therapy. A personalized approach tailored specifically for each individual should include considering the primary language spoken by the patient as well as culture, age, cognitive function, and health literacy level.

Simple language with clearly defined technical terms used along with open-ended questions as well as visual materials like demonstration videos/pictures or handouts may prove highly useful during education sessions. It is crucial not to wait until severe discomfort before seeking medication as once pain becomes extreme it becomes much harder to control and may require stronger medications.

Nurses should help patients understand the typical progression of pain medication prescribed through the pain ladder model. Patients need to comprehend why nonopioids need to come first before adding opioids or adjuvants into the regimen. Acute surgical pain patients, in particular, must know that although opioids might initially provide relief, their ultimate aim should be reducing dependency through intravenous, oral, and then nonopioids prescription.

Patients must also be educated on the need to use only as much pain relief medication as necessary to reach the intended pain goal. If their provider prescribes two tablets every four to six hours, for instance, it’s wiser for them to start with just one and gradually add on additional pain relievers as required. They should be advised against exceeding prescribed amounts as soon as they start feeling any relief. Before initiating any medication treatment plan, patients must receive proper instruction about its name, dose, route, and frequency of administration.

It’s also essential that any special instructions regarding when it should be taken such as with or without food, be written for the patient as well as storage tips to protect medications safely away from children by either keeping out of reach or locking up safely.

Every time they receive medication, patients should be educated on its potential adverse side effects as well as when to report them. When opioids are prescribed, patients should understand the potential risk for constipation, respiratory depression and addiction, and also be advised that taking opioid medication could make them feel sleepy. Additionally, they must not consume alcohol, drive heavy machinery, take any unapproved drugs while on such medicines or take other drugs not approved by their prescriber at that time.

Patients often hold incorrect assumptions about pain management that require being addressed. Therefore, it’s crucial that an assessment be completed of each individual and any misconceptions discovered. For instance, they might fear taking opioids due to concerns they will become dependent. Although long-term opioid usage could potentially lead to dependence issues, short-term use should still be weighed against its benefits regarding being tapered as quickly as possible.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- In patients undergoing pain management treatment, what do the potential consequences of untreated substance use disorder?

- How can you as a healthcare provider minimize the risk of opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain?

- What are the potential advantages and disadvantages of long-term narcotic therapy for chronic pain management?

Non-Pharmacological Pain Alternatives

Nonpharmacological interventions may be combined with or without pharmaceutical medicines as they often provide tremendous benefits. As with all treatments, nonpharmacological interventions must be documented within a plan of care to determine their ability to fulfill pain relief goals effectively. Non-pharmacological pain management techniques may fall under either complementary or alternative medicine categories. Though sometimes interchanged, there is a distinct distinction: complementary therapies work alongside pharmaceutical pain treatments while alternative therapies are practiced as an alternative from standard pharmaceuticals.

Substance Use Disorder

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), one out of every seven Americans reports having experienced some form of substance use disorder in the last month (25).

Defining Substance Use Disorder (SUD)

Substance Use Disorder, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), is defined as any pattern of substance abuse which leads to clinically significant impairment or distress, from substances including alcohol, cannabis, hallucinogens, inhalants, opioids, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, stimulants, and tobacco (25). A substance use disorder (SUD) may range in severity between mild, moderate, or severe cases.

Addiction, which is one of the more serious forms of substance use disorder (SUD), refers to continued drug consumption despite negative consequences, and should be seen as a medical disease rather than character description. Therefore, people living with SUDs should not be labeled abusers, addicts, alcoholics, or “medication seekers,” since such language can be stigmatizing and isolating. To reduce the stigma surrounding substance use disorders we focus instead on medical diagnoses of each specific case and offer effective solutions.

Though Substance Use Disorder (SUD) is considered treatable, recovering can still be challenging for many. Individuals suffering from an SUD often cannot stop taking the substance in question without experiencing excruciating withdrawal symptoms. Sometimes another drug may help wean patients off problematic opioids, such as methadone, buprenorphine or naltrexone which are all widely prescribed to treat opioid addictions. Patients may benefit from participating in programs like 12-Step Facilitation Therapy, outpatient counseling to better understand addiction and triggers, or inpatient rehabilitation at full-time facilities that offer supportive environments without distractions or temptations for recovery.

Definitions of Use and Abuse

Understanding the differences between dependence and addiction is paramount for understanding opioid misuse and abuse. Dependence refers to physical tolerance that requires increased doses to produce desired responses. Addiction occurs when that threshold has been passed and greater amounts must be administered for desired responses to be realized. Withdrawal from drugs will often bring on physical symptoms like shaking, tremors, nausea, and vomiting.

Addiction refers to an emotional need for drugs with desirable effects that leads to strong drug seeking behavior. Individuals who are opioid dependent may oscillate between feeling sick without taking their prescribed dose and experiencing the desired “high” after taking it. Being addicted is the driving force for individuals trying to obtain and take more opioids in order to avoid withdrawal symptoms.

Withdrawal symptoms include the following (16):

- Intense drug cravings

- Depression, withdrawal fears, anxiety

- Sweating, watery eyes, runny nose

- Restlessness, yawning

- Diarrhea

- Fever and chills

- Muscle spasms

- Tremors and joint pain

- Stomach cramps

- Nausea and vomiting

- Elevated heart rate and blood pressure

Populations at Risk

People at risk for opioid dependence and addiction are seen in every age, gender, ethnicity, and culture. Physical dependence varies as a genetic component has been identified, which influences how quickly a person may slide from occasional use to physical need and addiction to the drug (26). Susceptible populations have typically included the homeless, alcoholics and those with personality or mental health disorders who look for opiates to block the emotional pain of life stressors.