Course

GI Bleed: An Introduction

Course Highlights

- In this GI Bleed: an Introduction course, we will learn about the pathophysiology of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract and list examples of underlying conditions that cause gastrointestinal bleeding.

- You’ll also learn the signs and symptoms of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of the nursing interventions and care plans related to gastrointestinal bleeding.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 1

Course By:

Abbie Schmitt

MSN, RN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

Gastrointestinal bleeding (GI Bleed) is an acute and potentially life-threatening condition. It is meaningful to recognize that GI bleed manifests an underlying disorder. Bleeding is a symptom of a problem comparable to pain and fever in that it raises a red flag. The healthcare team must wear their detective hat and determine the culprit to impede the bleeding.

Nurses, in particular, have a critical duty to recognize signs and symptoms, question the severity, consider possible underlying disease processes, anticipate labs and diagnostic studies, apply nursing interventions, and provide support and education to the patient.

Epidemiology

The incidence of Gastrointestinal Bleeding (GIB) is broad and comprises cases of Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) and lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB). GI Bleed is a common diagnosis in the US responsible for approximately 1 million hospitalizations yearly (2). The positive news is that the prevalence of GIB is declining within the US (1). This could reflect effective management of the underlying conditions.

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is more common than lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) (2). Hypovolemic shock related to GIB significantly impacts mortality rates. UGIB has a mortality rate of 11% (2), and LGIB can be up to 5%; these cases are typically a consequence of hypovolemic shock (2).

Certain risk factors and predispositions impact the prevalence. Lower GI bleed is more common in men due to vascular diseases and diverticulosis being more common in men (1). Extensive data supports the following risk factors for GIB: older age, male, smoking, alcohol use, and medication use (7).

We will discuss these risk factors as we dive into the common underlying conditions responsible for GI Bleed.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever cared for a patient with GIB?

- Can you think of reasons GIB is declining in the US?

- Do you have experience with patients with hypovolemic shock?

Etiology/ Pathophysiology

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding includes any bleeding within the gastrointestinal tract, from the mouth to the rectum. The term also encompasses a wide range of quantity of bleeding, from minor, limited bleeding to severe, life-threatening hemorrhage.

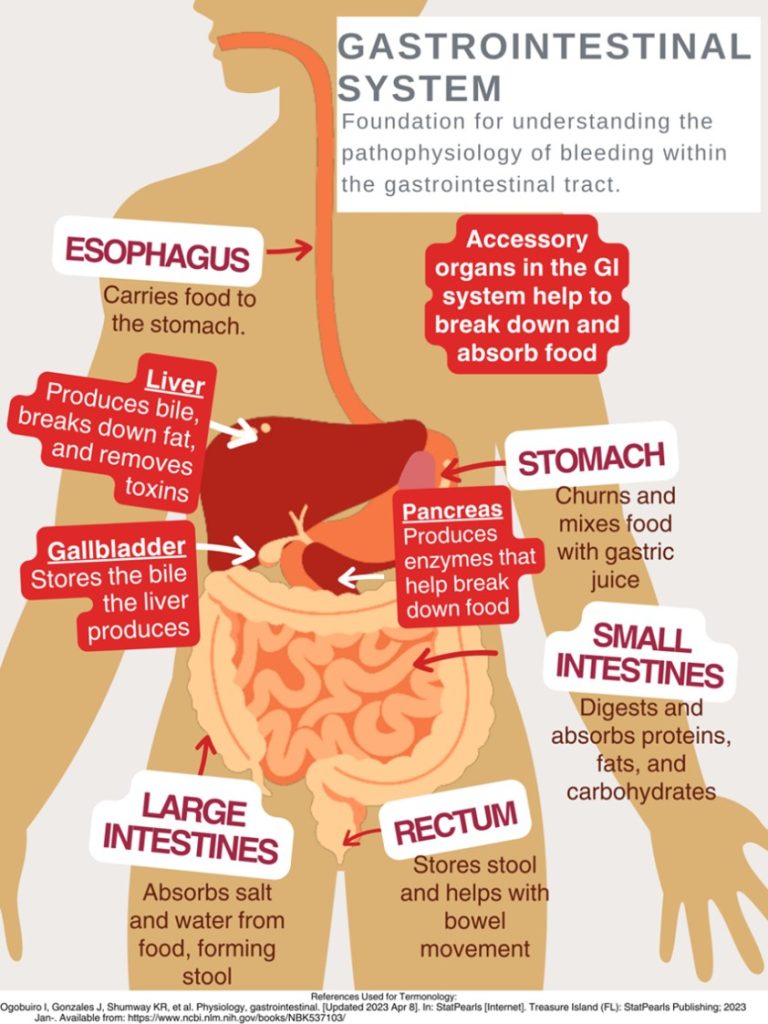

We will review the basic anatomy of the gastrointestinal system and closely examine the underlying conditions responsible for upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

Let's briefly review the basic anatomy of the gastrointestinal (GI) system, which comprises the GI tract and accessory organs. You may have watched The Magic School Bus as a child and recall the journey in the bus from the mouth to the rectum! Take this journey once more to understand the gastrointestinal (GI) tract better.

The GI tract consists of the following: oral cavity, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and anal canal (5). The accessory organs include our teeth, tongue, and organs such as salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas (5). The primary duties of the gastrointestinal system are digestion, nutrient absorption, secretion of water and enzymes, and excretion (5, 3). Consider these essential functions and their impact on each other.

This design was created on Canva.com on August 31, 2023. It is copyrighted by Abbie Schmitt, RN, MSN and may not be reproduced without permission from Nursing CE Central.

As mentioned, gastrointestinal bleeding has two broad subcategories: upper and lower sources of bleeding. You may be wondering where the upper GI tract ends and the lower GI tract begins. The answer is the ligament of Treitz. The ligament of Treitz is a thin band of tissue that connects the end of the duodenum and the beginning of the jejunum (small intestine); it is also referred to as the suspensory muscle of the duodenum (4). This membrane separates the upper and lower GI tract. Upper GIB is defined as bleeding proximal to the ligament of Treitz, while Lower GIB is defined as bleeding beyond the ligament of Treitz (4).

Upper GI Bleeding (UGIB) Etiology

Underlying conditions that may be responsible for the UGIB include:

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Esophagitis

- Foreign body ingestion

- Post-surgical bleeding

- Upper GI tumors

- Gastritis and Duodenitis

- Varices

- Portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG)

- Angiodysplasia

- Dieulafoy lesion

- Gastric antral valvular ectasia

- Mallory-Weiss tears

- Cameron lesions (bleeding ulcers occurring at the site of a hiatal hernia

- Aortoenteric fistulas

- Hemobilia (bleeding from the biliary tract)

- Hemosuccus pancreaticus (bleeding from the pancreatic duct)

(1, 4, 5, 8. 9)

Pathophysiology of Variceal Bleeding. Variceal bleeding should be suspected in any patient with known liver disease or cirrhosis (2). Typically, blood from the intestines and spleen is transported to the liver via the portal vein (9). The blood flow may be impaired in severe liver scarring (cirrhosis). Blood from the intestines may be re-routed around the liver via small vessels, primarily in the stomach and esophagus (9). Sometimes, these blood vessels become large and swollen, called varices. Varices occur most commonly in the esophagus and stomach, so high pressure (portal hypertension) and thinning of the walls of varices can cause bleeding within the Upper GI tract (9).

Liver Disease + Varices + Portal Hypertension = Recipe for UGIB Disaster

Lower GI Bleeding (LGIB) Etiology

- Diverticulosis

- Post-surgical bleeding

- Angiodysplasia

- Infectious colitis

- Ischemic colitis

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Colon cancer

- Hemorrhoids

- Anal fissures

- Rectal varices

- Dieulafoy lesion

- Radiation-induced damage

(1, 4, 5, 9)

Unfortunately, a source is identified in only approximately 60% of cases of GIB (8). Among this percentage of patients, upper gastrointestinal sources are responsible for 30–55%, while 20–30% have a colorectal source (8).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How is the GI Tract subdivided?

- Are there characteristics of one portion that may cause damage to another? (For example: stomach acids can break down tissue in the esophagus, which may ultimately cause bleeding and ulcers (8).

- Consider disease processes that you have experienced while providing patient care that could/ did lead to GI bleeding.

Laboratory and Diagnostic Testing

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy identify the source of bleeding in 80–90% of patients (4). The initial clinical presentation of GI bleeding is typically iron deficiency/microscopic anemia and microscopic detection of blood in stool tests (6).

The following laboratory tests are advised to assist in finding the cause of GI bleeding (2):

- Complete blood count

- Hemoglobin/hematocrit

- International normalized ratio (INR), prothrombin time (PT), and activated partial thromboplastin time (PTT)

- Liver function tests

Low hemoglobin and hematocrit levels result from blood loss, and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) may be elevated due to the GI system's breakdown of proteins within the blood (9).

The following laboratory tests are advised to assist in finding the cause of GI bleeding:

- EGD (esophagogastroduodenoscopy)- Upper GI endoscopy

- Clinicians can visualize the upper GI tract using a camera probe that enters the oral cavity and travels to the duodenum (9)

- Colonoscopy- Lower GI endoscopy/ (9)

- Clinicians can visualize the lower GI tract.

- CT angiography

- Used to identify an actively bleeding vessel

Signs and Symptoms

Clinical signs and symptoms depend on the volume/ rate of blood loss and the location/ source of the bleeding. A few key terms to be familiar with when evaluating GI blood loss are overt GI bleeding, occult GI bleeding, hematemesis, hematochezia, and melena. Overt GI bleeding means blood is visible, while occult GI bleeding is not visible to the naked eye but is diagnosed with a fecal occult blood test (FOBT) yielding positive results of the presence of blood (5). Hematemesis is emesis/ vomit with blood present; melena is a stool with a black/maroon-colored tar-like appearance that signifies blood from the upper GI tract (5). Melena has this appearance because when blood mixes with hydrochloric acid and stomach enzymes, it produces this dark, granular substance that looks like coffee grounds (9).

Mild vs. Severe Bleeding

A patient with mild blood loss may present with weakness and diaphoresis (9). Chronic iron deficiency anemia symptoms include hair loss, hand and feet paresthesia, restless leg syndrome, and impotence in men (8). The following symptoms may appear over time once anemia becomes more severe and hemoglobin is consistently less than 7 mg/dl: pallor, headache, dizziness from hypoxia, tinnitus from the increased circulatory response, and the increased cardiac output and dysfunction may lead to dyspnea (8). Findings of a positive occult GI bleed may be the initial red flag.

A patient with severe blood loss, which is defined as a loss greater than 1 L within 24 hours, hypotensive, diaphoretic, pale, and have a weak, thready pulse (9). Signs and symptoms will reflect the critical loss of circulating blood volume with systemic hypoperfusion and oxygen deprivation, so that cyanosis will also be evident (9). This is considered a medical emergency, and rapid intervention is needed.

Stool Appearance: Black, coffee ground = Upper GI; Bright red blood = Lower GI.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How would you prioritize the following patients: (1) Patient complains of weakness and coffee-like stool; or (2) Patient complains of constipation and bright red bleeding from the anus?

- Have you ever witnessed a patient in hypovolemic shock? If yes, what symptoms were most pronounced? If not, consider the signs.

- What are ways that the nurse can describe abnormal stool?

History and Physical Assessment

History

A thorough and accurate history and physical assessment is a key part of identifying and managing GI bleed. Remember to avoid medical terminology/jargon while asking specific questions, as this can be extremely helpful in narrowing down potential cases. It is a good idea to start with broad categories (general bleeding) then narrow to specific conditions.

Assess for the following:

- Previous episodes of GI Bleed

- Medical history with contributing factors for potential bleeding sources (e.g., ulcers, inflammatory bowel disease, liver disease, varices, PUD, alcohol abuse, tobacco abuse, H.pylori, diverticulitis) (3)

- Contributory medications (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, bismuth, iron) (3)

- Comorbid diseases that could affect management of GI Bleed (8)

Physical Assessment

- Head to toe and focused Gastrointestinal, Hepatobiliary, Cardiac and Pancreatic

- Assessments

Assess stool for presence of blood (visible) and anticipate orders/ collect specimen for occult blood testing. - Vital Signs

Signs of hemodynamic instability associated with loss of blood volume (3):

- Resting tachycardia

- Orthostatic hypotension

- Supine hypotension

- Abdominal pain (may indicate perforation or ischemia)

- A rectal exam is important for the evaluation of hemorrhoids, anal fissures, or anorectal mass (3)

Certain conditions place patients at higher risk for GI bleed. For example, patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) have a five times higher risk of GIB and mortality than those without kidney disease (2).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Are there specific questions to ask if GIB is suspected?

- What are phrases from the patient that would raise a red flag for GIB (For example: “I had a stomach bleed years ago”)

- Have you ever noted overuse of certain medications in patients?

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever shadowed or worked in an endoscopy unit?

- Name some ways to explain the procedures to the patient?

Treatment and Interventions

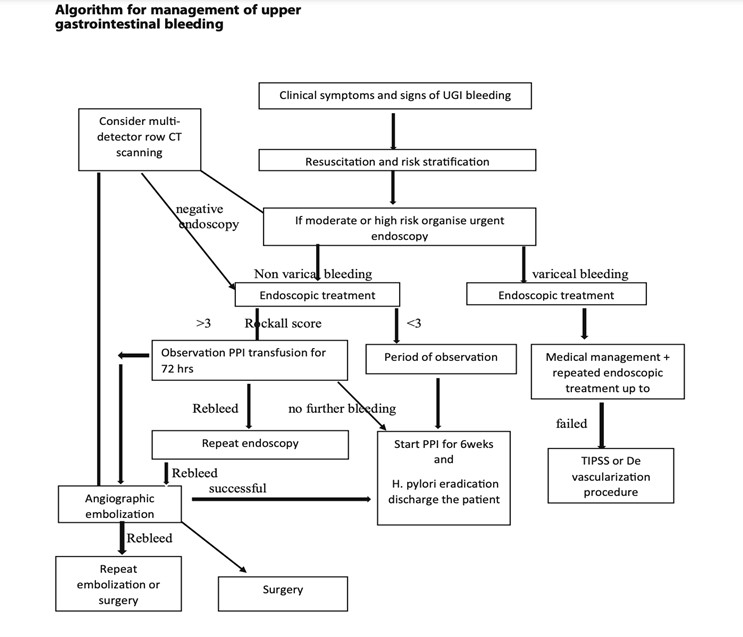

Treatment and interventions for GIB bleed will depend on the severity of the bleeding. Apply the ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation) prioritization tool appropriately with each unique case. Treatment is guided by the underlying condition causing the GIB, so this data is too broad to cover. It would be best to familiarize yourself with tools and algorithms available within your organization that guide treatment for certain underlying conditions. Image 2 is an example of an algorithm used to treat UGIB (8). The Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score (GBS) tool is another example of a valuable tool to guide interventions. Once UGIB is identified, the Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score (GBS) can be applied to assess if the patient will need medical intervention such as blood transfusion, endoscopic intervention, or hospitalization (4).

Unfortunately, there is currently a lack of tools available for risk stratification of emergency department patients with lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) (6). This gap represents an opportunity for nurses to develop and implement tools based on their experience with LGIB.

(8)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Are you familiar with GIB assessment tools?

- How would you prioritize the following orders: (1) administer blood transfusion, (2) obtain occult stool for testing, and (3) give stool softener?

The first step of nursing care is the assessment. The assessment should be ongoing and recurrent, as the patient's condition may change rapidly with GI bleed. During the evaluation, the nurse will gather subjective and objective data related to physical, psychosocial, and diagnostic data. Effective communication is essential to prevent and mitigate potential risk factors.

Subjective Data (Client verbalizes)

- Abdominal pain

- Nausea

- Loss of appetite

- Dizziness

- Weakness

Objective Data (Clinician notes during assessment)

- Hematemesis (vomiting blood)

- Melena (black, tarry stools)

- Hypotension

- Tachycardia

- Pallor

- Cool, clammy skin

Nursing Interventions

Ineffective Tissue Perfusion:

- Monitor vital signs frequently to assess blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation changes.

- Obtain IV access.

- Administer oxygen as ordered.

- Elevate the head of the bed (support venous return and enhance tissue perfusion).

- Administer blood products (packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma) as ordered to replace lost blood volume.

Acute Pain:

- Assess the patient's pain (quantifiable pain scale)

- Administer pain medications as ordered.

- Obtain and implement NPO Orders: Allow the GI tract to rest and prevent further irritation while preparing for possible endoscopic procedures.

- Apply heat/cold therapy for comfort.

Risk for Decreased Cardiac Output

- Assess the patient's heart rate and rhythm. (Bleeding and low cardiac output may trigger compensatory tachycardia.) (9)

- Assess and monitor the patient's complete blood count.

- Assess the patient's BUN level.

- Monitor the patient's urine output.

- Perform hemodynamic monitoring.

- Administer supplemental oxygenation as needed.

- Administer intravenous fluids as ordered.

- Prepare and initiate blood transfusions as ordered.

- Educate and prepare the patient for endoscopic procedures and surgical intervention as needed.

Risk for Deficient Fluid Volume:

- Monitor intake and output.

- Maintain hydration.

- Administer intravenous fluids as ordered.

- Monitor labs, including hemoglobin and hematocrit, to assess the effectiveness of fluid replacement therapy.

- Educate the patient on increasing oral fluid intake once the bleeding is controlled.

- Vital signs

- Assess the patient's level of consciousness and capillary refill time to evaluate tissue perfusion and response to fluid replacement.

- Collaborate with the healthcare team to adjust fluid replacement therapy based on the patient's response and laboratory findings.

Nursing Goals / Outcomes for GI Bleed:

- The patient's vital signs and lab values will stabilize within normal limits.

- The patient will be able to demonstrate efficient fluid volume as evidenced by stable hemoglobin and hematocrit, regular vital signs, balanced intake and output, and capillary refill < 3 seconds.

- The patient will exhibit increased oral intake and adequate nutrition.

- The patient will verbalize relief or control of pain.

- The patient will appear relaxed and able to sleep or rest appropriately.

- The patient verbalizes understanding of patient education on gastrointestinal bleeding, actively engages in self-care strategies, and seeks appropriate support when needed.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How can the nurse advocate for a patient with GIB?

- Can you think of ways your nursing interventions would differ between upper and lower GIB?

- Have you ever administered blood products?

- What are possible referrals following discharge that would be needed? (Example: gastroenterology, home health care)

Case Study

Mr. Blackstool presents to the emergency department with the following:

CHIEF COMPLAINT: "My stool looked like a ball of black tar this morning."

He also reports feeling "extra tired" and "lightheaded" for 3-5 days.

HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS: The patient is a 65-year-old tractor salesman who presents to the emergency room complaining of the passage of black stools, fatigue, and lightheadedness. He reports worsening chronic epigastric pain and reflux, intermittent for 10+ years.

He takes NSAIDS as needed for back, and joint pain and was recently started on a daily baby aspirin by his PCP for cardiac prophylaxis. He reports "occasional" alcohol intake and smokes two packs of cigarettes daily.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION: Examination reveals an alert and oriented 65-YO male. He appears anxious and irritated. Vital sips are as follows. Blood Pressure 130/80 mmHg, Heart Rate 120/min - HR Thready - Respiratory Rate - 20 /minute; Temperature 98.0 ENT/SKIN: Facial pallor and cool, moist skin are noted. No telangiectasia of the lips or oral cavity is noted. The parotid glands appear full.

CHEST: Lungs are clear to auscultation and percussion. The cardiac exam reveals a regular rhythm with an S4. No murmur is appreciated. Peripheral pulses are present but are rapid and weak.

ABDOMEN/RECTUM: The waist shows a rounded belly. Bowel sounds are hyperactive. Percussion of the liver is 13 cm (mal); the edge feels firm. Rectal examination revealed a black, tarry stool. No Dupuytren's contractions were noted.

LABORATORY TESTS: Hemoglobin 9gm/dL, Hematocrit 27%, WBC 13,000/mm. PT/PTT - normal. BUN 46mg/dL.

Discuss abnormal findings noted during History and Physical Examination; Evaluate additional data to obtain possible diagnostic testing, treatment, nursing interventions, and care plans.

Conclusion

After this course, I hope you feel more knowledgeable and empowered in caring for patients with Gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB). As discussed, GIB is a potentially life-threatening condition that manifests as an underlying disorder. Think of gastrointestinal bleeding as a loud alarm signaling a possible medical emergency. Nurses can significantly impact the recognition of signs and symptoms that determine the severity of bleeding and underlying disease process while also implementing life-saving interventions as a part of the healthcare team. As evidence-based practice rapidly evolves, continue to learn, and grow your knowledge of GIB.

References + Disclaimer

- DiGregorio AM, Alvey H. Gastrointestinal bleeding. [Updated 2023 Jun 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537291/

- Graham, & Carlberg, D. J. (Eds.). (2019). Gastrointestinal emergencies: evidence-based answers to key clinical questions. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98343-1

- Kaur, A., Baqir, S. M., Jana, K., & Janga, K. C. (2023). Risk of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with end-stage renal disease: The Link between Gut, Heart, and Kidneys. Gastroenterology Research & Practice, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/9986157

- Kumar, Verma, A., & Kumar T, A. (2021). Management of Upper GI bleeding. Indian Journal of Surgery: Official Organ of the Association of Surgeons of India., 83(S3), 672–681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-019-02055-3

- Ogobuiro I, Gonzales J, Shumway KR, et al. Physiology, gastrointestinal. [Updated 2023 Apr 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537103/

- Ramaekers, R., Perry, J., Leafloor, C., & Thiruganasambandamoorthy, V. (2020). Prediction model for 30-day outcomes among emergency department patients with lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health, 21(2), 343–347. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2020.1.45420

- Saydam ŞS, Molnar M, Vora P. The global epidemiology of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding in general population: A systematic review. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023 Apr 27;15(4):723-739. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i4.723. PMID: 37206079; PMCID: PMC10190726.

- Tadros, & Wu, G. Y. (Eds.). (2021). Management of occult GI bleeding: a clinical guide. Humana Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71468-0

- Williams, L. S., & Hopper, P. D. (2019). Understanding medical-surgical nursing. F.A. Davis Company.

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate