Course

Kentucky Renewal Bundle

Course Highlights

- In this Kentucky Renewal Bundle course, we will learn about diagnosis of pediatric abusive head trauma, and why it is important for nurses to recognize the signs.

- You’ll also learn the implications and long-term outcomes of unaddressed subconscious biases in healthcare and why it is important for providers to recognize and remove any biases that could impact their ability to offer equitable care.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of the mechanism of action of invasive and noninvasive ventilation.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 14

Course By:

Various Authors

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

Kentucky Alzheimer’s and Dementia Review

Introduction

Dementia is a broad term that describes a significant decline in cognitive abilities that interferes with a person’s daily life [1]. Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most prevalent form of dementia, accounting for at least two-thirds of dementia cases in individuals aged 65 and older [1]. AD is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by an insidious onset and progressive impairment of cognitive and behavioral functions, including memory, comprehension, language, attention, reasoning, and judgment [1][2]. Although Alzheimer's disease (AD) itself is not fatal through direct mechanisms, it increases susceptibility to complications that can lead to premature death including aspiration pneumonia which occurs when the disease causes difficulty in swallowing, leading to the inadvertent inhalation of food particles, liquids, or gastric fluids into the lungs [1].

In 2022, Alzheimer's disease was the seventh leading cause of death in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [3]. This is a decrease from its previous position as the sixth leading cause of death before the COVID-19 pandemic, which ranked fourth in 2022 [3]. Alzheimer's disease often appears after the age of 65, known as late-onset AD (LOAD) [3][4]. However, early-onset AD (EOAD), which occurs before age 65, is less common and affects about 5% of patients with AD [4]. EOAD often presents with atypical symptoms and with aggressive progress, leading to delayed diagnosis and a more severe disease course [5].

Over the past decade, there have been significant advancements in identifying biomarkers for the early and specific diagnosis of AD. These include neuroimaging markers from amyloid and tau PET scans, as well as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and plasma markers such as amyloid, tau, and phospho-tau levels [6].

While there is no cure for Alzheimer's disease, treatments are available to manage and alleviate some symptoms. Recent advancements in medication and the discovery of new biomarkers have shown promise in moderating the disease's progression.

Warning Signs and Symptoms of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias

Alzheimer's disease features gradual and progressive neurodegeneration due to neuronal cell death [1][7]. The neurodegenerative process often initiates in the entorhinal cortex, a region within the hippocampus [1][8]. Genetic factors contribute to both early and late-onset AD. Trisomy 21, for example, presents a risk factor for early-onset dementia [9]. Alzheimer's disease (AD) symptoms vary depending on the disease stage, which classifies into distinct levels of cognitive impairment and disability. These stages include the preclinical or presymptomatic stage, mild cognitive impairment, and the dementia stage, further divided into mild, moderate, and severe stages [1][10].

This staging system differs from the diagnostic criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) [1]. The initial and most common symptom of typical AD includes episodic short-term memory loss [11]. Individuals often struggle to retain added information while their long-term memories remain intact. As the disease progresses, impairments in problem-solving, judgment, executive functioning, and organizational skills become evident [11]. Early in the disease, instrumental activities of daily living, such as driving, managing finances, cooking, and planning, suffer [1].

As cognitive decline advances, individuals may experience language disorders and impaired visuospatial skills. In the moderate to late stages, neuropsychiatric symptoms like apathy, social withdrawal, disinhibition, agitation, psychosis, and wandering become more prevalent [1][12]. Late-stage symptoms can include difficulty with learned motor tasks (dyspraxia), olfactory dysfunction, sleep disturbances, and extrapyramidal motor signs such as dystonia, akathisia, and Parkinsonian symptoms [1][12]. In the final stages, primitive reflexes, incontinence, and complete dependence on caregivers are common [1][12].

AD involves multiple factors and includes many known risk factors. Age serves as the most significant factor, with advancing age as the primary contributor. The prevalence of AD doubles with every 5-year increase in age starting from age 65 [13]. Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) increase the risk of developing AD and contribute to dementia caused by strokes or vascular dementia [14]. Recognizing CVD as a modifiable risk factor for AD has become more common.

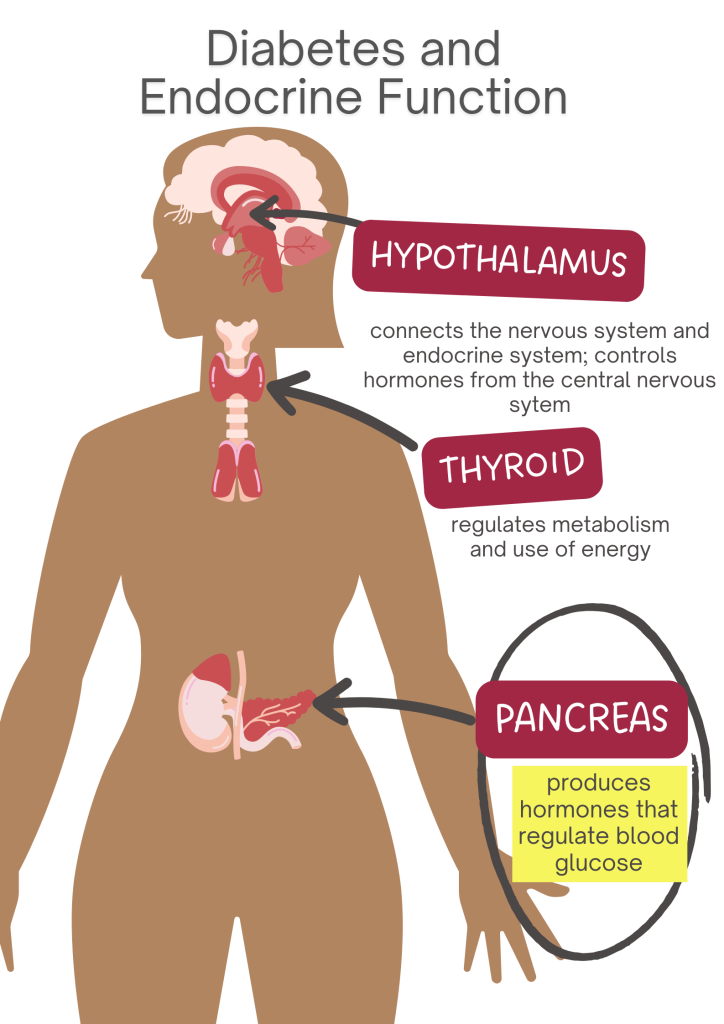

Obesity and diabetes are also important modifiable risk factors for AD [15]. Obesity can impair glucose tolerance and increase the risk of developing type II diabetes [1]. Chronic hyperglycemia can lead to cognitive impairment by promoting the accumulation of beta-amyloid (A-beta) and neuroinflammation [1][16]. Obesity further amplifies the risk by triggering the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and promoting insulin resistance [16].

Other potential risk factors for AD include traumatic head injury, depression, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, higher parental age at birth, smoking, family history of dementia, increased homocysteine levels, and the presence of the APOE e4 allele [1][17]. Having a first-degree relative with AD increases the risk of developing the disease by 10% to 30% [18]. Individuals with two or more siblings with late-onset AD face a threefold higher risk than the general population [1][19].

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How does understanding the different onset ages and progression patterns of Alzheimer's Disease (AD), along with the recent advancements in biomarkers and treatments, influence the approach to diagnosing and managing AD in patients?

- What might be the implications of the progressive nature of Alzheimer's Disease on an individual's daily life in the initial stages compared to the later stages?

- Considering the various risk factors for Alzheimer's Disease, how can lifestyle modifications influence the progression or onset of the disease?

Importance of Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Communication for Memory Concerns

Early detection and diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease (AD) are critical for effective management and care planning [20]. A thorough history-taking and comprehensive physical examination are fundamental in diagnosing AD. Gathering information from family and caregivers is also vital, as patients may lack insight into their condition. Evaluating a client's functional abilities, encompassing both basic activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), offers import information about their cognitive and functional status. IADLs require advanced planning and cognitive skills, including tasks like shopping, managing finances, filing taxes, preparing meals, and housekeeping.

In addition to medical history, inquire about the patient's social history, including alcohol use and any history of street drug use. These factors can influence cognitive function and require consideration in the diagnostic process.

Conduct a physical exam, including a neurological exam and mental status assessment, to evaluate the AD stage and rule out other conditions. The neurological exam in AD may appear normal except for anosmia. Anosmia also occurs in patients with Parkinson's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and traumatic brain injury (TBI) with or without dementia, but not in individuals with vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) or depression [1][21].

Perform and document cognitive assessments such as the Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE) or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Exam (MOCA). The MOCA evaluates patients with mild cognitive impairment more effectively than the MMSE [22][23]. Another cognitive screening test, the Mini-Cog exam, involves a clock drawing test and a three-item recall [24]. The results of the Mini-Cog remain consistent regardless of the individual's level of education.

In the advanced stages of AD, patients may exhibit more focal neurological signs, including apraxia, aphasia, frontal release signs, and primitive reflexes [1] [25]. As the disease progresses, patients may become mute and unresponsive to verbal requests, leading to increased dependence on caregivers and becoming confined to bed and entering a persistent vegetative state.

During a mental status examination, evaluating multiple cognitive domains is important to determine the extent of cognitive decline in Alzheimer's Disease (AD) [1]. These domains encompass concentration, attention, recent and remote memory, language abilities, visuospatial skills, praxis, and executive functions [1][26]. Regular follow-up appointments for individuals with AD should incorporate a comprehensive mental status examination to monitor disease progression and the emergence of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Effective communication techniques are essential when discussing memory concerns with the patient and their caregiver. Clear, empathetic communication helps in building trust and ensuring that the patient and caregiver understand the diagnosis, treatment options, and care plans. This approach fosters a supportive environment, enabling better management of the disease and improving the quality of life for both the patient and the caregiver.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Why is early detection and diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease considered critical for effective management and care planning?

- How can effective communication techniques improve the management and quality of life for individuals with Alzheimer's Disease and their caregivers?

Tools for Assessing a Patient’s Cognition

Cognitive assessment uses various tools to evaluate various aspects of cognitive function, which diagnose and manage conditions such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) and other dementias. These tools build a clinical understanding of care needs through ongoing interactions with the patient and caregiver. Customize the choice of assessment tools to fit clinician preferences, practice composition, workflows, and clinical goals. Here are some commonly used tools

- Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE): used for a quick assessment of cognitive function.

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA): More sensitive than the MMSE for detecting mild cognitive impairment.

- Mini-Cog: Involves a clock drawing test and three-item recall, useful in primary care settings.

- Functional Assessment Staging Test (FAST): For staging dementia.

- Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): For staging and evaluating dementia severity.

Use these tools alongside other diagnostic procedures such as blood tests, imaging (CT, MRI), and neuropsychological testing to evaluate

Documentation Requirements

Documentation of cognitive-relevant history should include factors contributing to cognitive impairment, such as psychoactive medications, chronic pain syndromes, infection, depression, and other brain diseases [28]. Medical decision-making documentation should cover the current and progression of the patient’s disease and the need for referrals to rehabilitative, social, legal, financial, or community services.

Patients without a firm diagnosis need documentation confirming cognitive impairment and a narrative history supporting the suspicion of potential cognitive impairment [28]. Use standardized tools for cognitive assessments and keep the full instrument raw scoring and results available for Medicare Administrative Contractor review if requested.

Required Tools and Assessments

Document the following standardized tools within the medical record:

- Cognitive assessment tools: Mini-Cog©, GPCOG, Short Montreal Cognitive Assessment (s-MoCA) [31].

- Functional assessment tools: Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living, Lawton-Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale (IADL) [32].

- Dementia staging tools: Functional Assessment Staging Test (FAST), Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR® Dementia Staging Instrument), Dementia Severity Rating Scale (DSRS), Global Deterioration Score (GDS) [33].

- Neuropsychiatric assessment tools: Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q), BEHAV5+©, Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) [34].

Additional Documentation

Additional documentation of cognitive-relevant history should include:

- Medication reconciliation

- Evaluation of home and vehicle safety

- Identification of social supports and caregivers

- Advance care planning and palliative care needs

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Why is comprehensive documentation essential in the management of cognitive impairment, and how does it influence the quality of care and support for patients?

- How do the use and documentation of standardized assessment tools impact management and care planning for patients with cognitive impairment?

- How does the selection and use of various cognitive assessment tools influence the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias?

Background and Introduction to CPT® Code 99483

The Alzheimer’s Association advocates for Medicare reimbursement for services to improve detection, diagnosis, and care planning for patients with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (ADRD). This advocacy led to the approval of Medicare procedure code G0505 in January 2017, later replaced by CPT code 99483 in January 2018 [35]. CPT code 99483 reimburses physicians and eligible billing practitioners for a clinical visit that produces a written care plan [35].

Who Is Eligible for Comprehensive Care Planning Services?

Provide cognitive assessment and care plan services under CPT code 99483 when a comprehensive evaluation of a new or existing patient with signs or symptoms of cognitive impairment is necessary [35]. This evaluation aims to establish or confirm a diagnosis, etiology, and severity of the condition. If any required elements are missing or unnecessary, use the appropriate evaluation and management (E/M) code instead.

Requirements for CPT Code 99483

To bill under CPT code 99483, perform the following service elements [28]:

- Cognition-focused evaluation, including a pertinent history and examination

- Medical decision-making of moderate or high complexity

- Functional assessment (e.g., this includes basic and instrumental activities of daily living as well as decision-making capacity).

- Use of standardized instruments to stage dementia (e.g., Functional Assessment Staging Test [FAST], Clinical Dementia Rating [CDR]) [30].

- Medication reconciliation and review for high-risk medications

- Evaluation for neuropsychiatric and behavioral symptoms, including depression, using standardized instruments

- Assessment of safety, both within the home environment and in other settings, including considerations for motor vehicle operation if relevant.

- Identification of caregivers, their knowledge, needs, social supports, and willingness to take on caregiving tasks

- Development and periodic updating of an Advance Care Plan

- Develop a comprehensive written care plan that addresses neuropsychiatric and neurocognitive symptoms, outlines functional limitations, and includes referrals to community resources. Document and share this plan with the client and/or caregiver.

This service involves 50 minutes of face-to-face time with the patient and/or family or caregiver. Do not report cognitive assessment and care plan services if any essential elements are either absent or deemed unnecessary. Instead, use the appropriate evaluation and management (E/M) code [28].

Assessment Settings and Documentation

Evaluate the first nine assessment elements of CPT code 99483 during the care planning visit or across multiple visits using billing codes (often E/M codes) [36]. Include results of assessments conducted before the care plan visit if they remain valid or update them at the time of care planning. Complete assessments that require a care partner or caregiver before the clinical visit and provide them to the clinician for the care plan.

Cognitive Assessment and Care Planning Billing Codes

Use Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 99483 for a clinical visit that assesses cognitive impairment and establishes a care plan for patients with dementia or other cognitive impairments, including Alzheimer's disease [27][28]. This code applies to patients at any stage of impairment and once every 180 days billed to the insurance company.

Additional CPT codes related to cognitive assessment and care planning [27][28]:

- 99324–99337: Home visits for new patients

- 99341–99350: Home visits for established patients

- 99366–99368: Medical team conferences

- 99497: Advanced care planning for the first 30 minutes

- 97129, 97130: Cognitive functioning intervention services

Screening and Billing for Cognitive Assessment

Medicare Annual Wellness Visits (AWV) require screening for cognitive impairment [29]. Identify cognitive impairment during routine visits through direct observation or information from the patient, family, friends, caregivers, and others. Develop a cognitive assessment and care plan during a separate visit.

Bill CPT code 99483 apart from the annual wellness visit due to the time and medical decision-making [28]. If providing both services at the same visit, use a -25 modifier [28].

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How does the use of specific CPT codes, such as 99483, facilitate the assessment and care planning for patients with cognitive impairments, including Alzheimer's Disease?

- How do the various service elements required for billing under CPT code 99483 contribute to a comprehensive approach to managing patients with cognitive impairment?

- What challenges do healthcare providers face in fulfilling the requirements for CPT code 99483, and how can they address these challenges to ensure comprehensive care for patients with cognitive impairment?

Eligible Providers and Settings

Any healthcare professional qualified to report Evaluation and Management (E/M) services can offer this service, including physicians (MD and DO), nurse practitioners (NP), clinical nurse specialists (CNS), certified nurse midwives (CNM), and physician assistants (PA) [28]. Practitioners must provide documentation substantiating a moderate-to-elevated level of complexity in their medical decision-making, following E/M guidelines [28]. Conduct care planning visits in the office, other outpatient settings, home, domiciliary, rest home settings, or via telehealth. Even when using telehealth, include all required service elements for CPT 99483 [36].

Utilizing a Care Plan Template

The required elements for this service may benefit from a standardized care plan template. This template can simplify communication and track patient care and outcomes but must allow for narrative unique to the patient. Discuss and give the written care plan to the patient and/or family or caregiver and document this face-to-face conversation in the clinical note. Share the care plan with other providers involved in the patient's care to ensure continuity and coordination.

Frequency of Service and Auditing

A single physician or other qualified health care professional reports CPT code 99483 no more than once every 180 days [28]. Revise the care plan at intervals and whenever the patient’s clinical or caregiving status changes. Ensure that revisions to reports exclude any service elements of CPT 99483 when billed through alternative E/M codes, such as those for chronic care management or non-face-to-face consultation [28][36].

The Alzheimer's Association's Cognitive Impairment Care Planning Toolkit is a valuable resource for practitioners, providing comprehensive guidance on creating effective care plans for patients with cognitive impairment.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What impact does the approval of CPT code 99483 have on the detection, diagnosis, and care planning for patients with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias?

- How does meeting the specific requirements of CPT code 99483 enhance the quality of care and outcomes for patients with cognitive impairment?

- How does the assessment setting and thorough documentation of the first nine assessment elements required by CPT code 99483 influence the effectiveness of care planning for patients with cognitive impairment?

- How does the flexibility in eligible providers and settings for CPT code 99483 enhance access to comprehensive care planning for patients with cognitive impairment?

- How does the use of a standardized care plan template enhance the effectiveness and coordination of care for patients with cognitive impairment?

Current Treatments Available to the Patient

The primary approach to treatment manages symptoms of Alzheimer's disease (AD). Two categories of drugs treat AD: cholinesterase inhibitors and partial N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonists [1].

Cholinesterase Inhibitors

Cholinesterase inhibitors work by increasing the levels of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter involved in learning, memory, and cognitive functions [1][37]. Three drugs in this category have received FDA approval for treating AD [1][37][38]:

- Donepezil:

- Preferred medication

- Used in AD with mild dementia

- Rapid and reversible inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase

- Administered once daily in the evening

- Rivastigmine:

- Used in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and mild dementia stages

- Slow, reversible inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase

- Available in oral and transdermal formulations

- Galantamine:

- Approved for MCI and mild dementia stages

- Rapid, reversible inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase

- Available as a twice-daily tablet or once-daily extended-release capsule

- Not suitable for individuals with end-stage renal disease or severe liver dysfunction

Common side effects of cholinesterase inhibitors include gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea [37]. They may also cause bradycardia, cardiac conduction defects, and syncope due to increased vagal tone [37]. These medications are contraindicated in patients with severe cardiac conduction abnormalities [37].

Partial N-Methyl D-Aspartate (NMDA) Antagonist: Memantine

Memantine acts as a partial NMDA antagonist that blocks NMDA receptors and slows intracellular calcium accumulation [39]. The FDA has approved it for the treatment of moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease. Side effects may include dizziness, body aches, headaches, and constipation [39]. Combine memantine with cholinesterase inhibitors like donepezil, rivastigmine, or galantamine in individuals with moderate to severe AD [39].

Disease-Modifying Therapies for Alzheimer’s Disease

AD treatment managed symptoms. However, understanding AD's pathophysiology and improving diagnostic testing led to new disease-modifying therapies. These therapies target the disease's mechanisms, even in preclinical and presymptomatic stages.

Recent Therapy Approvals

- Aducanumab [40]:

- FDA accelerated approval in June 2020

- Shown to reduce amyloid-beta plaque in the brain

- Did not meet the primary phase III trial endpoint of clinical improvement

- Lecanemab [41]:

- FDA accelerated approval in January 2023

- Reduced amyloid-beta burden in the brain

- Phase III trial showed a 27% slowing of disease progression

- Donanemab [42]:

- Expected FDA approval in 2023

- Reduced amyloid-beta burden in the brain

- Slowed cognitive decline by 35%

Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities (ARIA)

ARIA results from an immune response to amyloid-targeting therapies, causing capillary leakage and hemorrhages in cerebral vascular walls [43]. Two types exist: ARIA edema (ARIA-E) and ARIA hemorrhage (ARIA-H). Key risk factors for developing ARIA include the apolipoprotein E4 allele and cerebral amyloid angiopathy findings in brain MRI [43].

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How do cholinesterase inhibitors function in the management of Alzheimer's disease, and what factors should clinicians consider when prescribing these medications?

- How do partial NMDA antagonists like memantine and recent disease-modifying therapies impact the treatment and progression of Alzheimer's disease?

Other Management Strategies in Alzheimer’s Disease

Manage symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and psychosis in the mid to late stages of the disease. Avoid tricyclic antidepressants due to their anticholinergic effects, which worsen cognitive impairment [44]. Use antipsychotic medications with caution for acute agitation when other interventions have failed, and the patient's or caregiver's safety is at risk. Try SSRIs like citalopram and anticholinesterases like donepezil before considering antipsychotics.

Prefer second-generation antipsychotics over first-generation antipsychotics due to their safer profile and fewer extrapyramidal side effects [45]. Brexpiprazole, approved by the FDA in May 2023 for treating agitation associated with dementia due to AD, serves as an example. Use the lowest effective dose when prescribing antipsychotics [46]. Avoid benzodiazepines as they worsen delirium and agitation [47].

Non-Pharmacological Interventions

- Behavioral Strategies: Establishing a familiar and secure environment is essential. This includes addressing personal comfort needs, offering security objects, redirecting attention when necessary, removing hazardous items, and avoiding confrontational situations.

- Sleep Disturbances: Addressing mild sleep disturbances through non-pharmacological strategies such as exposure to sunlight, daytime exercise, and establishing a bedtime routine.

- Exercise: Regular aerobic exercise slows the progression of AD.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are the implications of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease, and how should healthcare providers manage symptoms like anxiety, depression, and psychosis in patients with AD?

- How do non-pharmacological interventions contribute to the management and quality of life of patients with Alzheimer's disease?

Conclusion

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the prevalent form of dementia, impacting cognitive and behavioral functions, and is a leading cause of death among the elderly [1]. AD presents with symptoms that progress from mild memory loss to severe cognitive and functional decline [1]. Early detection and diagnosis are critical for effective management, involving a thorough assessment of cognitive and functional abilities [48]. While there is no cure for AD, symptomatic treatments such as cholinesterase inhibitors and NMDA antagonists can help manage symptoms, and recent advancements in disease-modifying therapies offer new hope for slowing disease progression [49].

Comprehensive care planning, including regular cognitive assessments and tailored interventions, is essential for optimizing patient outcomes and supporting caregivers. Regular follow-ups and a multidisciplinary approach to treatment, incorporating both pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies, can improve the quality of life for individuals with AD and their families.

Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma

Introduction and Objectives

Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma (AHT), also known as Shaken Baby Syndrome, includes an array of symptoms and complications resulting from injury to a child or infant’s head and brain after violent or intentional shaking or impact. There are approximately 1,300 reported cases of AHT each year and it is the leading cause of child abuse deaths nationally. For those children who survive, most suffer lifelong complications and disabilities (7).

This serious and tragic injury may be a challenge to diagnose because obvious signs of injury may not be easily detectable right away, and those responsible for the injuries may avoid taking the child for treatment (4). Therefore, it is incredibly important for healthcare professionals who work in pediatrics or emergency medicine to be able to identify at-risk individuals and recognize signs and symptoms of potential victims of AHT. It is also 100% preventable, and proper training on how to mitigate the risks and situations that lead to AHT can help healthcare professionals reduce the incidence of this horrific injury. Upon completion of this course, the learner will be able to:

- Identify risk factors and common mechanisms of injury for pediatric abusive head trauma.

- Describe signs and symptoms and diagnostic tools used to identify pediatric abusive head trauma.

- List potential outcomes of pediatric abusive head trauma and their prevalence.

- Understand the legal considerations of mandated reporters, process of reporting, and penalties for pediatric abusive head trauma perpetrators in the state of Kentucky

- Identify ways that societal and healthcare interventions can help reduce the prevalence of pediatric abusive head trauma

Epidemiology/Risk Factors

Though pediatric abusive head trauma most often occurs in children under age 5, the majority of these injuries are in children under the age of 1 year. There is a slight difference in incidence between genders, with 57.9% of victims being male and 41.9% being female. There is a peak occurrence of AHT between 3 and 8 months (4). Babies of this age are particularly vulnerable for a multitude of reasons, including large head size, weak neck muscles, fragile and developing brains, and the discrepancy in strength between infant and abuser. Sleep deprivation paired with longer and louder crying spells of very young infants sets the stage for high levels of caregiver frustration, which often precedes AHT injuries. The perpetrator is almost always a parent or caregiver (7).

Besides infant age, there are many social factors that increase the risk of AHT, including a lack of childcare experience, young or poorly supported parents, single-parent homes, low socioeconomic status, low education level, and a history of violence. These factors paired with a lack of prenatal care or parenting classes often leads to poorly prepared parents who have not been taught to anticipate crying spells or how to deal with the frustration in a safe manner (7).

Unfortunately, Kentucky has one of the highest rates of child abuse in the country. In 2019, there were more than 130,000 reports of suspected abuse or neglect, and 15,000 of those had substantial evidence to support abuse had occurred. Of those, nearly 76 were nearly fatal or fatal, and 32 of those were due to pediatric abusive head trauma(1).

Case Study

A Nursery nurse on a Labor, Delivery, and Postpartum unit is providing discharge information to the parents of a 2 day old baby girl, Violet, who is going home today. This is the first child for both parents. They are 19 years old, living in an apartment together while the mother works part time as a waitress and the father works full time for a lawn mowing company. The child’s maternal grandmother lives nearby and will be helping the mother care for the baby the first few weeks and then watching the baby a few days per week when the mother returns to work.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Which factors put this child at an increased risk of being abused?

- Which factors are protective against abuse?

- What resources might the nurse connect these parents with in order to maximize their support network once they are discharged?

Pathophysiology of Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma

While anyone can sustain a head injury, the relatively large size of young children’s heads paired with their weak and underdeveloped neck muscles is what makes them particularly susceptible to AHT. When a child’s head moves around forcefully, the brain moves around within the skull, which can tear blood vessels and nerves, causing permanent damage. Bruising and bleeding may occur when the brain collides with the inside of the skull or fractured pieces of skull. Finally, swelling of the brain may occur, which builds up pressure inside the skull and makes it difficult for the body to properly circulate oxygen to the brain (6).

It should be noted that bouncing or tossing a child in play, sudden stops or bumps in the car, and falls from furniture (or less than 4 feet) do not involve the force required to mimic the injuries of AHT (7).

Also important to understand is that AHT is a broad term used to describe the injury, but there are a collection of various mechanisms of injury within AHT. Among these different causes are Shaken Baby Syndrome (SBS), blunt impact, suffocation, intentional dropping or throwing, and strangulation. It is recommended to classify all of these injuries as AHT so as to avoid any confusion or challenges in court if multiple mechanisms of injury were involved (4).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Consider why it is important to know that falls from less than 4 feet do not typically cause much injury to babies and young children. What would you think if an infant presents with a serious brain injury and the parents state he fell off the couch?

- What sort of problems could occur in the litigation process if a child is diagnosed with Shaken Baby Syndrome but it is then revealed the child was thrown to the ground?

- Young children fall all the time while running, riding bikes, and climbing on playground equipment. What makes this less dangerous than an infant being shaken or thrown?

Diagnosis of Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma

Parents or caregivers who have inflicted injury onto a child may delay seeking treatment for fear of consequences. It is important to gather a thorough history and be on the lookout for inconsistent stories, changing details, or mechanism of injury that does not match the severity of symptoms (7).

Symptoms that typically lead caregivers to seek treatment for their child include:

- Decrease in responsiveness or change in level of consciousness

- Poor feeding

- Vomiting

- Seizures

- Apnea

- Irritability

Upon exam, these children may exhibit:

- Bradycardia

- Bulging fontanel

- Irritability or lethargy

- Apnea

- Bruising

A lack of any external injuries or obvious illnesses when presenting with these symptoms should alert the healthcare professional to the possibility of AHT, particularly in young children or infants. Additionally, unexplained fractures, particularly of the skull or long bones, bruising around the head or neck, or any bruising in a child less than 4 months are red flags (4).

An ophthalmology consult to assess for retinal hemorrhage should be obtained. The force used with AHT can cause a shearing effect with the retina and is visible with a simple fundal exam of the eye. This type of injury does not typically occur with accidental or blunt head trauma and is typically considered highly indicative of abuse. That same shearing force often causes bleeding within the brain, and subdural hematomas are often revealed on CT or MRI (4).

Any of the above criteria, or other suspicious story or injuries, should be reported for further investigation. Mild injuries are harder to detect but only occur around 15% of the time. Severe injury from AHT accounts for 70% of cases (4).

Case Study Cont.

Baby Violet is now 5 weeks old and is brought to the ED by her parents. Her mother reports that she has been eating poorly and acting strange since this morning. Her father reports he thinks she has been sleeping excessively for 2 days now. On exam, the baby is found to have a bulging fontanel, slow heart rate, and a bruise on the side of her head. Her mother states she sustained that bruise when she rolled off of her changing table yesterday.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What additional exam information would be necessary/helpful at this time? Specialty consult? Imaging?

- What assessment finding or diagnostic data might alleviate some suspicion that this is an abuse case? What would contribute to the suspicion?

Outcomes and Sequelae

For children diagnosed with even mild to moderate AHT, the prognosis is fairly grim. Up to 25% of children with AHT end up dying from their injuries, and for those who survive, 80% will have lifelong disabilities of varying severity (7).

The most common complications and disabilities include: blindness, hearing loss, developmental delays, seizures, muscle weakness or spasticity, hydrocephalus, learning disabilities, and speech problems. Lifelong skilled care and therapies are often needed for these children, accruing over $70 million in healthcare costs in the United States annually (4).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What characteristics of AHT would lead to long term disabilities like blindness, muscle spasticity, and speech problems?

- How do you think the cost of social programs and parental support programs within a community might compare to the costs of abuse investigation and healthcare costs for abused children?

Legal Considerations in the State of Kentucky

In the state of Kentucky, anyone with a reasonable suspicion that abuse or neglect is occurring is mandated by law to report the incident, and there are legal consequences (from misdemeanor all the way to felony) for willfully failing to make a report. For healthcare professionals, this is particularly important to note, as you will come in contact with many different types of families, injuries, and stories, and must remain vigilant in assessing for abuse (5).

A report of suspected abuse should be made at the first available opportunity and can be made by contacting the child abuse hotline (1-877-KYSAFE1), local law enforcement, Kentucky State Police, or the Cabinet for Health and Family Services. The child’s name, approximate age and address, as well as the nature and description of injuries, and the name and relationship of the alleged abuser should all be included in the report (9).

Once a report has been made, the Department for Community Based Services will determine if an investigation is warranted. If the home is deemed to be unsafe or there is a threat of immediate danger to a child, the child will be removed from the home, but in all other cases, every effort will be made to maintain the family (5).

Case Study

It is later determined that Baby Violet was violently shaken by her mother during a crying spell one evening. During legal proceedings for the incident, it is revealed that the grandmother witnessed this abuse.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Did the grandmother break any laws in this scenario?

- Is it likely that the child would stay in the home in this scenario, or do you think her safety is at a continued risk and removal would be necessary?

Prevention

While accurate detection of AHT is incredibly important, another key consideration for this injury and its poor outcomes, is that these incidents are 100% preventable. Much of the time, AHT is preceded by extreme frustration by a parent or caregiver when an infant is crying for long periods or is inconsolable. Proper education and preparedness about when and why this occurs, and what to do when it does, can help prevent AHT from occurring. For healthcare professionals who regularly care for infants, children, and expecting or new parents, there is a huge potential for positive impact (2).

Identifying those most at risk is a great starting place and new parenting courses, educational discussion and pamphlets, as well as regular check-ins are extremely beneficial for at-risk families. Young or inexperienced families, families without a lot of external support, or those with low socioeconomic status or poor education should be looked at first.

Once the most at risk families have been identified, provide them with information and services that may help reduce risks. These interventions are useful for anyone with an infant or small child, but special attention and close follow up should be given to those with more risk factors (8).

- Educate about infant crying: The PURPLE Crying program is particularly useful for this and includes facts and common symptoms of excessive or colicky infant crying. PURPLE stands for:

- Peak of Crying, with crying increasing weekly after birth and peaking around 8 weeks

- Unexpected, where crying may come and go with no apparent cause

- Resists soothing, where your baby won’t settle no matter what you try

- Pain like face, where your baby looks like they are in pain even if nothing is wrong

- Long-lasting, with crying lasting as long as 5 hours

- Evening, with excessive crying being more common in the evening or at night (8)

2. Enhance parenting skills: Let parents know it is okay to feel frustrated. Take a deep breath, count to 10, place your infant in a safe place and walk away for a few minutes to collect yourself. Many parents don’t know that this is okay to do (3).

3. Strengthen socioeconomic support: Make sure families are aware of and utilizing access to supportive services like WIC to help ease financial strain.

4. Emphasize social support and positive parenting: Ask about nearby help in the form of relatives or friends. Encourage them to reach out for emotional support, or even a break from caring for the infant. Connect families with community resources like motherhood support groups or playdates. Schedule for early childhood home visits (2).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Think about the populations you work with. How can you check in to make sure families have adequate support and decrease their risk of child abuse?

- What areas are the easiest to address at your current job? The most difficult?

Conclusion

Though the goal is for there to be no scenarios where children suffer head trauma at the hands of an abuser, there is a long way to go before that objective can be reached. In the meantime, healthcare professionals must be vigilant in maintaining a high level of suspicion for pediatric abusive head trauma whenever they are caring for children. Understanding contributing risk factors, as well as signs and symptoms, and how to properly assess for and diagnose pediatric abusive head trauma will lead to more accurate detection, appropriate treatment, and hopefully better outcomes. On the other end of things, those in a position to influence parenting education and community health standards should consider the ways in which caregiver frustration might be better handled to prevent the abuse from even occurring. There is much work to be done when it comes to AHT, but well informed medical professionals is an essential step in the right direction.

Health Equity is a rising area of focus in the healthcare field as renewed attention is being given to ongoing data regarding discrepancies and gaps in the accessibility, expanse, and quality of healthcare delivered across racial, gender, cultural, and other groups. Yes, there are some differences in healthcare outcomes purely based on biological differences between people of different genders or races, but more and more evidence points to the vast majority of healthcare gaps stemming from individual and systemic biases.

Policy change and restructuring is happening at an institutional level across the country, but this will only get us so far. In order for real change to occur and the gaps in healthcare to be closed, there must also be awareness and change on an individual level. Implicit, or subconscious, bias has the potential to change the way healthcare professionals deliver care in subtle but meaningful ways and must be addressed to modernize healthcare and reach true equity.

This Kentucky Implicit Bias training meets the “Implicit Bias” requirement needed for Kentucky nursing license renewal.

What is Implicit Bias?

So what is implicit bias and how is it affecting the way healthcare is delivered? Simply put, implicit bias is a subconscious attitude or opinion about a person or group of people that has the potential to influence the actions and decisions taken when providing care. This differs from explicit bias which is a conscious and controllable attitude (using racial slurs, making sexist comments, etc). Implicit bias is something that everyone has and may be largely unaware of how it is influencing their understanding of and actions towards others. The way we are raised, our unique life experiences, and an individual’s efforts to understand their own biases all affect the opinions and attitudes we have towards other people or groups (7). This Kentucky Implicit Bias training course will increase your awareness of implicit bias in your nursing practice.

This can be both a positive or a negative thing. For example if a patient’s loved ones tells you they are a nurse, you may immediately feel more connected to them and go above and beyond the expected care as a “professional courtesy.” This doesn’t mean you dislike your other patients and their loved ones, just that you feel more at ease with a fellow healthcare professional which shapes your thoughts and behaviors in a positive manner.

More often though, implicit biases have a negative connotation and can lead to care that is not as empathetic, holistic, or high quality as it should be. Common examples of implicit bias in healthcare include:

- Thinking elderly patients have lower cognitive or physical abilities

- Thinking women exaggerate their pain or have too many complaints

- Assuming patients who state they are sexually active are heterosexual

- Thinking Black patients delay seeking preventative or acute care because they are passive about their health

- Assuming a chatty college student is asking for ADHD evaluation because she is lazy and wants medication to make things easier

On a larger, more institutional and societal level, the effects of bias create barriers such as:

- Underrepresentation of minority races as providers: in 2018 56.2% of physicians were white, while only 5% were Black and 5.8% Hispanic (2)

- Crowded living conditions and food deserts for minority patients due to outdated zoning laws created during times of segregation (17).

- Difficulty obtaining health insurance for minority or even LGBTQ clients, decreasing access to healthcare (3).

- Lack of support and acceptance for LGBTQ people in the home, workplace, or school as well as lack of community resources leads to negative social and mental health outcomes.

- Due to variations in the way disabilities are assessed, the reported prevalence of disabilities ranges from 12% to 30% of the population (15).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

Before introducing the implications and long-term outcomes of unaddressed implicit biases in healthcare, reflect on your practice and the clients you work with. This will help as we progress through this Kentucky implicit bias training course.

- Think about the facility where you work and the different types of clients you come into contact with each day. Are there certain types of people you assume things about just based on the way they look, their gender, or their skin color?

- In what ways do you think these assumptions might affect the way you care for your clients, even if you keep these opinions internal?

- How do you think you could try and re-frame some of these assumptions?

- Do you think being more aware of your internal opinions will change your actions the next time you work?

- Before the Kentucky Implicit Bias Training course requirement, how often did you consider implict bias?

- Reflecting on your personal nursing practice, why do you think Kentucky has added a requirement on Kentucky Implict Bias training?

Implications

Once you have an understanding of what implicit bias is, you may be wondering what it looks like on a larger scale and what it means in terms of healthcare discrepancies. More and more data stacks up each year with examples that span all types of diversity, from race to gender, age, disabilities, religion, sexual identification and orientation, and even Veteran status. Examples of what subconscious biases in healthcare may look like include:

- Medical training and textbooks are mostly commonly centered around white patients, even though many rashes and conditions may look very different in patients with darker skin or different hair textures. This can lead to missed or delayed diagnoses and treatment for patients of color (9).

- A 2018 survey of LGBTQ youth revealed 80% reporting their provider assumed they were straight or did not ask (12). And in 2014, over half of gay men (56%) surveyed who had been to a doctor said they had never been recommended for HIV screening, despite increased risk for the disease (10).

- A 2010 study found that women were more verbose in their encounters with physicians and may not be able to fit all of their complaints into the designated appointment time, leading to a less accurate understanding of their symptoms by their doctor (4). For centuries, any symptoms or behaviors that women displayed (largely related to mental health) that male doctors could not diagnose fell under the umbrella of “hysteria”, a condition that was not removed from the DSM until 1980 (20).

- When treating elderly patients, providers may dismiss a treatable condition as part of aging, skip preventative screenings due to old age, or overtreat natural parts of aging as though they are a disease. Providers may be less patient, responsive, and empathetic to a patient’s concerns or even talk down to them or not explain things because they believe them to be cognitively impaired (18).

- Minority, particularly Black or Hispanic patients, are often thought to be less concerned or more neglectful of their health, but minority patients are also most often those living in poverty, which goes hand in hand with crowded living conditions and food deserts due to outdated zoning laws created during times of segregation. This means less access to nutritious foods, fresh air, or clean water which has overall negative effects on health (mude). Minority patients are also still disproportionately uninsured, which leads to delayed or no care when necessary (3).

Although these are only a few examples, there are obvious and substantial consequences of these biases; which is why it is vital that we address them in this Kentucky Implicit Bias training course.

This has obvious negative connotations or repercussions at the time of care and can lead to client dissatisfaction or suboptimal treatment and missed preventative care, but over time the effects of implicit bias can add up and lead to even larger consequences. Examples include:

- A 2020 study found that Black individuals over age 56 experience decline in memory, executive function, and global cognition at a rate much faster than their white peers, often as much as 4 years ahead in terms of cognitive decline. Data in this study attribute the difference to the cumulative effects of chronically high blood pressure more likely to be experienced and undertreated for Black Americans (16).

- Lack of health insurance keeps many minority patients from seeking care at all. 25% of Hispanic people are uninsured and 14% of Black people, compared to just 8.5% of white people. This leads to lack of preventative care and screenings, lack of management of chronic conditions, delayed or no treatment for acute conditions, and later diagnosis and poorer outcomes of life threatening conditions (3).

- A 2010 study showed men and women over age 65 were about equally likely to have visits with a primary care provider, but women were less likely to receive preventative care such as flu vaccines (75.4%) and cholesterol screening (87.3%) compared to men (77.3% and 88.8% respectively) (4).

- About 12.9% of school aged boys are diagnosed and treated for ADHD, compared to 5.6% of girls, though the actual rate of girls with the disorder is believed to be much higher (5).

- Teenagers and young adults who are part of the LGBTQ community are 4.5 times more likely to attempt suicide than straight, cis-gender peers (11).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

For the purpose of this Kentucky Implicit Bias training, put yourself in a patient’s perspective and reflect on the following:

- Have you ever been a patient and had a healthcare professional assume something about you without asking or getting the whole story? How did that make you feel?

- How do you think it might affect you over time if every healthcare encounter you had went the same way?

Impact of Historic Racism

In addition to discrepancies in insurance status, representation in medical textbooks, and representation among medical professionals, there is a long history of systemic racism that has created generational trauma for minority families, leading to mistrust in the healthcare system and poorer outcomes for those marginalized communities.

Possibly one of the most infamous examples is the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. This 1932 experiment included 600 Black men, about two thirds of which had syphilis, and involved collecting blood and monitoring the progression of symptoms for research purposes in exchange for free medical exams and meals. Informed consent was not collected and participants were given no information about the study other than that they were being “treated for bad blood”, even though no treatment was actually administered. By 1943, syphilis was routinely and effectively treated with penicillin, however the men involved in the study were not offered treatment and their progressively worsening symptoms continued to be monitored and studied until 1972 when it was deemed unethical. Once the study was stopped, participants were given reparations in the form of free medical benefits for the participants and their families. The last participant of the study lived until 2004 (6).

The “father of modern gynecology,” Dr. J. Marion Sims, is another example steeped in a complicated and racially unethical past. Though he did groundbreaking work on curing many gynecological complications of childbirth, most notably vesicovaginal fistulas, he did so by practicing on unconsenting, unanesthetized, Black enslaved women. The majority of his work was done between 1845 and 1849 when slavery was legal and these women were likely unable to refuse treatment, sometimes undergoing 20-30 surgeries while positioned on all fours and not given anything for pain. Historically his work has been criticized because he achieved so much recognition and fame through an uneven power dynamic with women who have largely remained unknown and unrecognized for their contributions to medical advancement (23).

Another example is the story of Henrietta Lacks, a young Black mother who died of cervical cancer in 1951. During the course of her treatment, a sample of cells was collected from her cervix by Dr. Gey, a prominent cancer researcher at the time. Up until this point, cells being utilized in Dr. Gey’s lab died after just a few weeks and new cells needed to be collected from other patients. Henrietta Lacks’ cells were unique and groundbreaking in that they were thriving and multiplying in the lab, growing new cells (nearly double) every 24 hours. These highly prolific cells were nicknamed HeLa Cells and have been used for decades in the development of many medical breakthroughs, including studies involving viruses, toxins, hormones, and other treatments on cancer cells and even playing a prominent role in vaccine development. All of this may sound wonderful, but it is important to understand that Henrietta Lacks never gave permission for these cells to be collected or studied and her family did not even know they existed or were the foundation for so much medical research until 20 years after her death. There have since been lawsuits to give family members control over what the cells are used for, as well as requiring recognition of Henrietta in published studies and financial payments from companies who profited off of the use of her cells (15).

When considering all of the above scenarios, the common theme is a lack of informed consent for Black patients and the lack of recognition for their invaluable role in society’s advancement to modern medicine. It only makes sense that these stories, and the many others that exist, have left many Black patients mistrustful of modern medicine, medical professionals, or treatments offered to them, particularly if the provider caring for them doesn’t look like them or seems dismissive or unknowledgeable about their unique concerns. Awareness that these types of events occurred and left a lasting impact on many generations of Black families is incredibly important in order for medical professionals to provide empathetic and racially sensitive care.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

Consider the above-mentioned historic events and reflect on the following:

- Have you ever had a negative experience at a healthcare facility? How has that experience impacted your view of that facility or your opinion when others talk about that facility?

- How would you feel if you learned that a sample of your cells or a bodily fluid was taken without your consent and had been used for medical experimentation? What about if companies had made huge profits from something taken from your body?

- Even without monetary compensation, why do you think recognition for a person’s role in healthcare advancement through the use of their own body is important?

Exploring Areas of Bias

Culture

Cultural competence is a common buzzword used in healthcare training programs and information about various religions, ethnicities, beliefs, or practices is often integrated into medical training. Students and staff members are often reminded that the highest quality of care anticipates the unique cultural needs a client may have and aims to provide care that is holistic and respectful of cultural differences. An awareness of the potential variances in care, such as dietary needs, desire for prayer or clergy members, rituals around birth or death, beliefs surrounding and even refusal for certain types of treatments, are all certainly very important for the culturally sensitive healthcare professional to have (and the distinctions far too many for the scope of this course); however, there is also a fine line between being aware of cultural similarities and stereotyping. Since this course is a required California Implicit Bias training, it is essential that this topic is covered.

Clinicians should make sure to understand that people hold different identities, beliefs, and practices across racial, ethnic, and religious groups. Remember that just because someone looks a certain way or identifies with a certain group does not mean all people within that group are the same. Holding assumptions about clients of a particular race or religion, without getting to know the individual needs of your client, is a form of implicit bias and may cause your client to become uncomfortable or offended.

Simply asking clients if they have any cultural, dietary, or spiritual needs throughout the course of their care is often the best way to learn their needs without making assumptions or stereotyping. Overall, it should be thought of as extending care beyond cultural competence and working on partnership and advocacy for your client’s unique needs.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever cared for a client that you made an assumption about based on appearances and it turned out not to be true?

- Did your behavior or attitude towards that client change at all once you gained new information about them?

- Think about ways you could incorporate cultural questions into your plan of care and how it could improve your understanding of client needs.

Maternal Health

One of the most strikingly obvious places that implicit bias has tainted the healthcare industry is in maternal health. Repeatedly, statistics show that Black women experience twice the infant mortality rate and nearly four times the maternal mortality rate of non-Hispanic white women during childbirth.

Let those numbers sink in and realize that this is a crisis. Pregnancy and childbirth are natural processes, but do come with inherent risks for mother and baby; but in a modern society, women should feel comfortable and confident in their care, not scared they won’t be treated properly or even survive. Home births among Black women are on the rise as they seek to avoid the biases of the hospital setting and maintain control over their own experiences (21).

The reasons for this disparity and Black women fearing for their lives when birthing in hospitals are many. This disparity exists regardless of socioeconomic class or education, indicating that a more insidious culprit, implicit bias, is hugely responsible (21). In order for true change to come, this topic must be addressed in this California Implicit Bias training. A few notes that indicate the prevalence of implicit bias in healthcare throughout history are listed below:

- False beliefs about biological differences between white and black women date back to slavery, including the belief that Black women have fewer nerve endings, thicker skin, and thicker bones and therefore do not feel pain as intensely.

- These beliefs are obviously untrue, but subconscious bias towards those beliefs still exists as Black and Hispanic women statistically have their perceived pain rated lower by health care professionals and are offered appropriate pain management interventions less often than white peers.

- Complaints from minority patients that may indicate red flags for conditions such as preeclampsia or hypertension are often downplayed or ignored by healthcare professionals.

- Studies show healthcare professionals may believe minority patients are less capable of adhering to or understanding treatment plans and may explain their care in a condescending tone of voice not used with other patients.

- One in five Black and Hispanic women report poor treatment during pregnancy and childbirth by healthcare staff.

- These patients are less likely to feel respected or like a partner in their care and may be non-compliant with treatment recommendations due to feeling this way, however this just perpetuates the attitudes held by the healthcare providers (21).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Think about how a provider’s perception of a maternity client’s pain could snowball throughout the labor and delivery process. How do you think it might affect the rate of c-sections or other birth interventions if clients have not had their pain properly managed throughout labor?

- Pregnancy is a very vulnerable time. Think about how you would feel if you were experiencing a pregnancy and had fears or concerns and your provider did not seem to validate or respect you. Would you feel comfortable going into birth? How might added fears or stress impact the experience?

Reproductive Rights

Branching off of maternal health is reproductive justice. Biases surrounding the reproductive decisions of women may negatively impact the care they receive when seeking care for contraception or during pregnancy. While some of these inequities may be more profound for women of color, women of all races can be and are affected by biases surrounding reproduction, which is why it is being covered in this California Implicit Bias training course. Examples of ways implicit bias may affect care include:

- Some healthcare professionals may believe there is a “right” time or way to become pregnant and feel pregnancy outside of those qualifiers is undesirable; this can stem from personal or religious beliefs. While healthcare staff are certainly entitled to hold these beliefs in their personal lives, if the resulting implicit biases are left unchecked, they can lead to attitudes and actions that are less compassionate when caring for their clients. Clients may feel shamed or judged during their experiences instead of having their needs addressed (8). Variables that may be perceived as unacceptable or less desirable include:

- Age during pregnancy. Clinicians may feel differently about pregnant clients who are very young (teenagers) or even those who are in their 40s or 50s (8).

- Marital status during pregnancy. Healthcare professionals may have beliefs that clients should be married when having children and may have a bias against unmarried or single clients (8).

- Number or spacing of pregnancies. Professionals may hold beliefs about how many pregnancies are acceptable or how far apart they should be and may hold judgment against clients with a large number of children or pregnancies occurring soon after childbirth.

- Low-income and minority women are more likely to report being counseled to limit the number of children they have, as opposed to their white peers (15).

- Method of conception. Some healthcare professionals may have personal beliefs about how children should be conceived and may have negative opinions about pregnancies resulting from fertility treatments such as IVF or surrogacy (8).

- Personal or religious beliefs about contraception may also cause healthcare professionals to provide less than optimal care to clients seeking methods of birth control.

- Providers may believe young or unmarried clients should not be given access to contraception because they do not believe they should be engaging in sexual activity (8).

- Providers, or even some institutions such as Catholic hospitals, may withhold contraception from clients as they believe it to be immoral to prevent pregnancy.

- Providers may push certain types or usage of contraception onto clients that they feel should limit the number of children they have, even if this does not align with the desires of the client. This includes the use of permanent contraception such as tubal ligation (15).

- Providers may provide biased information about the types of contraception available, minimizing side effects or pushing for easier, more effective types of contraception (such as IUDs), despite a client’s questions, concerns, or contraindications (15).

- One study showed Black and Hispanic women felt pressured to accept a certain type of contraception based on effectiveness alone, with little concern for their individual needs or reproductive goals (15).

- Personal or religious beliefs about pregnancy termination may impact the care provided and counsel given to pregnant clients who may wish to consider termination. Providers who disagree with abortion on a personal level may find it difficult to provide clear and unbiased information about all options available to pregnant clients or may have a judgmental or uncompassionate attitude when caring for clients who desire or have had an abortion (8).

Case Study

Alexandria is a 22-year-old Hispanic woman who has always wanted a big family with 3-5 children. She met her current boyfriend in college when she was 19 and became pregnant shortly afterward. It was an uneventful pregnancy, and Alexandria had a vaginal delivery to a healthy baby girl at 39 weeks. When that child turned 2, Alexandria and her partner decided they would like to have another baby.

At 38 weeks gestation, Alexandria was at a prenatal appointment when her provider brought up her plans for contraception after the birth. The provider suggested an IUD and stated it could be placed immediately after birth, could be left in for 5 years, and would be 99% effective at preventing pregnancy. Alexandria stated she had an IUD when she was 17 and did not like some of the side effects, mostly abdominal cramping, and that she also might like to have another baby before the 5-year mark.

Her doctor stated “All birth control has side effects, and this one is the most effective. You are so young, do you really want 3 children by age 25 anyway?”

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What implicit biases does this healthcare professional hold about reproductive rights?

- How do you think those opinions are likely to affect Alexandria? Do you think she will change her mind or her future plans? Or do you think she will be more likely to disregard this provider’s advice and opinions moving forward?

- What are some potential negative consequences for Alexandria’s pregnancy prevention plans after this exchange with her doctor?

- Prior taking this Kentucky Implicit Bias course, were you aware of any implict biases regarding reproductive health?

How to Measure and Reduce Implicit Biases in Healthcare

Assessing for Bias

In order for change to occur, there is a broad spectrum of transitions in individual thought and policy that must occur. Evaluating for the presence, and the extent, of implicit bias is one of the first steps. This Kentucky Implicit Bias training will cover both individual and institutional level focuses.

On the individual level, possible action include:

- Identifying and exploring one’s own implicit biases. Everyone has them and we all need to reflect upon them. This goes beyond basic cultural competence and includes a deeper understanding of how your own experiences or environment may differ from someone else and may have caused you to feel or believe a certain way.

- Attending training or workshops provided by your job and completing exercises in self reflection will help you better understand where your biases are and the extent to which they may be impacting your behavior or actions at work and in your personal life.

- Reflecting on how one’s biases affect actions. Once you have recognized the internal opinions you hold, you can examine ways that those opinions may have been affecting your actions, behaviors, or attitudes towards others. Reflect on your care of patients at the end of each shift. Consider if you made assumptions about certain clients early on in their care. Think about ways those assumptions may have affected your interactions with the client. Think about if you cared for your clients in a way that you would want your own loved ones cared for.

- If you have the time, volunteer at events or in places that will expose you to people who are different from you. Use the opportunity to learn more about others, their lived experiences, and identify how often your implicit biases may be affecting your view of others before you even get to know them.

On an institutional level, the measurement of biases can be more streamlined and may utilize tools like surveys.

- Monitoring patient data and assessing for any broad gaps in diagnoses, preventative care and treatment rates, as well as health outcomes across racial, ethnic, gender, and other spectrums. Recognizing gaps or problem areas and assigning task forces to evaluate further and address the underlying issues.

- Regularly poll clients and employees of healthcare facilities to determine who might be experiencing effects of bias and when.

- Require employee participation in implicit bias presentations or courses, allowing employees to self identify areas where they may be biased.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- In what ways will your approach be different the next time you care for a client unlike yourself?

- Can you think of a policy or practice that your facility could change in order to provide more equitable care to the clients you serve?

- Do you have a better understanding of implicit bias in healthcare after taking this Kentucky Implicit Bias course?

Acting to Reduce Bias

Once the presence and extent of bias has been identified, individuals can make small, consistent changes to recognize and address those biases in order to become more self aware and intentional in their actions. Some possible ways to address and reduce implicit bias on an individual level include:

- Educating oneself and reframing biases. In order to change patterns of thinking and subsequent behaviors that may negatively impact others, you can work on broadening your views on various topics. This can be done through reading about the experiences of others, watching informational videos or documentaries, attending speaking engagements, and just listening to the experiences of others and gaining an understanding of how their lives might be different than yours.

- Understanding and celebrating differences. Once you can learn to see others for their differences and consider how you can adapt your care to help them achieve the best outcomes for their wellbeing, you are able to provide truly equitable care to your clients. This includes understanding differences in experiences, perceptions, cultures, languages, and realities for people different from yourself, recognizing when disparities are occurring, and advocating for change and equity.

When enough people have recognized and addressed their own implicit biases, advocacy can extend beyond individual care of clients and reach the institutional level where change is more easily seen (though no more important than the small individual changes). One of the most effective ways to make institutional level changes is through representation of minority groups in positions of power and decision making. Simply keeping structures as they are and dictating change without any evolution from leadership is not likely to be effective in the long term. Including minority professionals in positions of leadership or on decision making panels has the most potential to make true and meaningful change for hospitals and healthcare facilities.

Examples of institutional level changes include:

- Medical schools will need to take a broader, more inclusive approach when admitting future doctors, incentivise minority students to choose careers in healthcare, and invest in their retention and success (9).

- Properly training and integrating professionals like midwives and doulas into routine antenatal care and investing in practices like group visits and home births will give power back to minority women while still giving them safe choices during pregnancy (1).

- Universal health insurance, basic housing regulations, access to grocery stores, and many other socio-political changes can also work towards closing the gaps in accessibility to quality healthcare and may vary by geographic location (3).

- Community programs should be available to create safe spaces for connection and acceptance for LGBTQ people. Laws and school policy need to focus on how to prevent and react to bullying and violence against LGBTQ individuals (12).

- Cultural competence training in medical professions needs to include LGBTQ issues and data collection regarding this population needs to increase and be recognized as a medical necessity (12).

- Medical professionals must be trained in the history of inequality among women, particularly in regards to mental health, and proper, modern diagnostics must be used. The differences in communication styles of men and women should be taught as well (20).

- Medical facilities should emphasize respect of a client’s views on controversial topics such as pregnancy/birth, death, and acceptance or declining of treatments even if it conflicts with a staff members’ own beliefs (14).

- Healthcare facilities can adopt practices that are standardized regardless of age and include anti-ageism and geriatric focused training, including training about elder abuse (18).

Obviously each geographic area will have differing demographics depending on the populations they serve. What works at one facility may not work at another. Hearing from the community is beneficial for keeping things individualized and allows facilities to gain perspective from the local groups they serve.

- Town Hall style meetings, keeping hospital board members and employees local rather than outsourcing from travel companies (when possible), and encouraging community involvement from staff members are all great ways to keep a community centered facility and keep the lines of communication open for clients who may be having a different experience than their neighbor.

There are many things that will need to be done in order for equitable, bias-free healthcare to become a norm nationwide. However, taking the time to learn from this Kentucky Implicit Bias training, apply it to current practices, and continue to learn about others and their respective beliefs and cultures is just the beginning.

Suicide risks among nurses is a public health concern. The first and most profound way to address the troubling rates of suicide among nurses is to employ suicide prevention. For that matter, mandatory training, resources, and the establishment of policies and procedures are crucial within the operation of organizations. All healthcare providers are responsible for identifying and addressing situations which warrant intervention.

This Kentucky Suicide Prevention course meets the “Suicide Prevention” requirement needed for Kentucky nursing license renewal.

Introduction