Course

New Jersey APRN Bundle

Course Highlights

In this New Jersey APRN Bundle, we will learn about various topics applicable to APRNs in the state of New Jersey.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 30 , including 12 pharmacology contact hours.

Course By:

Various Authors

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

New Jersey Opioid Prescribing

Introduction

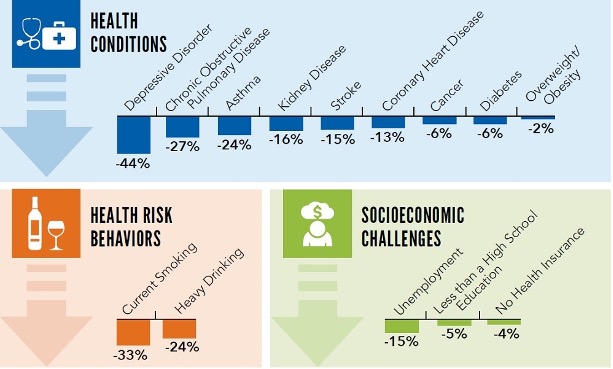

For centuries, humans have been using, developing, and synthesizing opioid compounds for pain relief. Opioids are essential for treating patients who are experiencing severe and sometimes even moderate pain. Chronic pain can negatively affect our lives. In 2011, the cost of chronic pain ranged from $560 to $635 billion in direct medical expenses, lost productivity, and disability. An estimated one in five U.S. adults has chronic pain (1).

Pharmacology of Opioids: Drug Class, Indications for Use, Most Prescribed Opioids, and their Effects.

Opioids usually bind to mu-opioid receptor sites, where they have agonist effects, providing pain relief, sedation, and sometimes feelings of euphoria. Opiates refer only to natural opioids derived from the poppy plant. The term "opioids" includes all-natural, semi-synthetic, and synthetic opioids.

Opioids are classified into several categories based on their origin and chemical structure:

- Natural Opioids (Opiates): These come from the opium poppy plant. Examples include morphine and codeine.

- Semi-Synthetic Opioids: These are natural opioids that are chemically modified. Examples include drugs like oxycodone, hydrocodone, oxymorphone, and hydromorphone.

- Synthetic Opioids: These opioids are entirely synthesized in a laboratory and do not have a natural source. Examples include fentanyl, tramadol, and methadone (1, 2).

Providers must always caution patients about the benefits and risks. The main advantage of opioid medication is that it will reduce pain and improve physical function.

A provider may use a 3-item Pain, Enjoyment of Life, and General Activity (PEG) Assessment Scale:

- What number best describes your pain on average in the past week?

- What number best describes how, during the past week, pain has interfered with your enjoyment of life?

- What number best describes how, during the past week, pain has interfered with your general activity?

(3)

The desired goal is improvement overall with opioid treatment (3). Providers should also go over potential side effects and cautions. Side effects include sedation, dizziness, confusion, nausea, vomiting, constipation, itching, pupillary constriction (miosis), and respiratory depression.

Providers must also discuss the importance of consistently taking medication as prescribed. Taking opioids in larger than prescribed dosage, or in addition to alcohol, other illicit substances, or other prescription drugs, can lead to severe respiratory depression and death. Missing dosages can lead to decreased pain control and possible opioid withdrawal symptoms. Individuals should not drive when taking opioids due to the sedating effects and decreased reaction times (4).

There are now thousands of different Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved opioids available for providers to prescribe. They can be administered via other routes and come in various potencies. The strength of morphine is the "gold standard" used when comparing opioids. A morphine milligram equivalent (MME) is the degree of µ-receptor agonist activity.

The following is a sample of some of the most prescribed opioids and their MME (5):

|

Opioid |

Conversion factor |

|

Opioid |

Conversion factor |

|

Codeine |

0.15 |

|

Morphine |

1.0 |

|

Fentanyl transdermal (in mcg/hr.) |

2.4 |

|

Oxycodone |

1.5 |

|

Hydrocodone |

1.0 |

|

Oxymorphone |

3.0 |

|

Hydromorphone |

5.0 |

|

Tapentadol† |

0.4 |

|

Methadone |

4.7 |

|

Tramadol§ |

0.2 |

To utilize this information, multiply the dose for each opioid by the conversion factor to determine the quantity in MMEs. For example, tablets containing hydrocodone 5 mg and acetaminophen 325 mg taken four times a day would include a total of 20 mg of hydrocodone daily, equivalent to 20 MME (5).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How often do you prescribe opioids to your patients? If so, which ones and what dosages?

- If you do not prescribe opioids, do you treat patients taking them?

- Have you ever felt hesitant about prescribing opioids? What were the reasons?

- What topics do you routinely cover when you discuss opioid prescriptions with your patients?

A Brief History

While the current opioid epidemic has caused devastating effects in recent years, destruction from opioids has been going on for centuries. In the early 1800s, physicians and scientists became aware of the addictive qualities of opium. This finding encouraged research to develop safer ways to deliver opioids for pain relief and cough suppression, which led to the development of morphine.

By the mid-1800s, with commercial production and the invention of the hypodermic needle, morphine became easier to administer. During the Civil War (1861 to 1865), injured soldiers were sometimes treated with morphine, and some developed lifelong addictions after the war.

Without other options for pain relief, physicians kept giving patients morphine as treatment. Early indicators that morphine should be used cautiously were largely ignored. Between 1870 and 1880, the use of morphine tripled. Even with the problems associated with opioids, they continued to serve a vital part in the pain treatment of patients, and their use and development continued (6).

Drug law enforcement started in 1914, but it wasn't until July 1, 1973, that the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was established in the United States. The Diversion Control Division oversees pharmaceuticals. Within this Division are five levels of controlled substances, which classify illicit and medicinal drugs.

In the U.S., opioid prescribing increased fourfold during 1999–2010. Along with the increase in opioid prescriptions during this time, how they were prescribed also changed; opioids were increasingly prescribed at higher dosages and for longer durations. The number of people who reported using OxyContin for non-medical purposes increased from 400,000 in 1999 to 1.9 million in 2002 and to 2.8 million in 2003. This was accompanied by a fourfold increase in overdose deaths involving prescription opioids (8).

In 2020, approximately 1.4 million people were diagnosed with opioid use disorder (OUD), of those associated with opioid painkillers, as opposed to 438,000 who have heroin-related OUD (1, 4). Over 100,000 people died of a drug overdose, with 85% involved in an opioid (1, 4).

Widespread efforts were made to combat this growing issue. The prescribing rate peaked and leveled off from 2010-2012 and has been declining since 2012. In 2021, an estimated 2.5 million adults had been diagnosed with OUD. However, the amount of MME of opioids prescribed per person is still around three times higher than in 1999 (5).

Controlled Substance Classification

Schedule I Controlled Substances

No medical use, lack of accepted safety for use under medical supervision, and high abuse potential.

Examples of Schedule I substances are methaqualone, heroin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), mescaline, methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), and marijuana (cannabis).

(7)

Schedule II/IIN Controlled Substances (2/2N)

High potential for abuse, which can lead to severe dependence. Refills are not allowed for these drugs. Schedule II drugs have the strictest regulations compared to other prescription drugs presently.

Examples include hydromorphone, methadone, meperidine, oxycodone, and fentanyl. Other narcotics in this class include morphine, opium, codeine, and hydrocodone.

Some examples of Schedule IIN stimulants include amphetamine, methamphetamine, and methylphenidate.

Other substances include amobarbital, glutethimide, secobarbital, and pentobarbital.

(7)

Schedule III/IIIN Controlled Substances (3/3N) (7)

There is less potential for abuse than substances in Schedules I or II, and abuse may lead to moderate or low physical dependence or high psychological dependence. Schedule III drugs are able to be prescribed verbally over the phone, with a paper prescription, or via electronic prescribing. Within a six-month timeframe from the original prescription date, Schedule III drugs have requirements such that the medication can only have five refills.

Include drugs containing not more than 90 milligrams of codeine per dosage unit like Acetaminophen with Codeine and buprenorphine.

Schedule IN non-narcotics include benzphetamine, phendimetrazine, ketamine, and anabolic steroids such as Depo®-Testosterone.

(7)

Schedule IV Controlled Substances

Have a low potential for abuse relative to substances in Schedule III. Similar to Schedule III drugs, Schedule IV drugs are able to be prescribed verbally over the phone, with a paper prescription, or via electronic prescribing. Within a six-month timeframe from the original prescription date, Schedule IV drugs have refill requirements such that the medications can only have five refills.

Examples include alprazolam, carisoprodol, clonazepam, clorazepate, diazepam, lorazepam, midazolam, temazepam, triazolam, and tramadol.

Schedule V Controlled Substances

It has a low potential for abuse relative to Schedule IV and primarily consists of medications that have small quantities of narcotics.

Examples include cough preparations containing not more than 200 milligrams of codeine per 100 milliliters or per 100 grams and ezogabine. Other Schedule V medication examples include ezogabine, pregabalin, and atropine/diphenoxylate. Partial prescription fills cannot occur more than six months after the prescription issue date. When a partial fill occurs, it is treated in the same manner and with the same regulations as a refill of the prescription.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How have your prescribing practices of opioids changed in response to the epidemic over time?

- What trends have you noticed in overall inpatient treatment plans regarding opioid prescribing trends (e.g., dose changes? or increase in opioid alternative therapies?)

- Do you think there is a stigma surrounding patients who are currently using opioids?

Opioid-Seeking Behaviors

Opioid use disorder (OUD) causes significant impairment and distress. Diagnosis is based on the following criteria: unsuccessful efforts to reduce or control use or use that leads to social problems and a failure to fulfill obligations at work, school, or home. The term Opioid use disorder is the preferred term; "opioid abuse or dependence" or "opioid addiction" have negative connotations and should be avoided. (9). Presently, it is estimated that OUD affects over 16 million people globally, with over 2 million in the United States experiencing this condition.

OUD occurs after a person has developed tolerance and dependence, resulting in a physical challenge to stop opioid use and increases the risk of withdrawal. Tolerance happens over time when a person experiences a reduced response to medication, requiring a larger amount to experience the same effect. Opioid dependence occurs when the body adjusts to regular opioid use. Unpleasant physical symptoms of withdrawal occur when medication is stopped. Symptoms of withdrawal include anxiety, mood changes, insomnia, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, etc. (9).

Patients who have OUD may or may not have practiced drug misuse. Drug misuse, the preferred term for "substance abuse," is the use of illegal drugs and the use of prescribed drugs other than as directed by a doctor, such as using more amounts, more often, or longer than recommended to or using someone else's prescription (9).

Some indications that a patient may be starting to have unintended consequences with their opioid prescription may include the following symptoms: craving, wanting to take opioids in higher quantities or more frequently, difficulty controlling use, or work, social, or family issues.

If providers suspect OUD, they should discuss their concerns with their patients nonjudgmentally and allow the patient to disclose related concerns or issues. Providers should assess the presence of OUD using the DSM-5 criteria.

Per the DSM-5, OUD is defined as repeated opioid use within 12 months leading to problems or distress with 2 or more of the following occurring:

- Prolonged opioid use despite worsening physical or psychological health

- Prolonged opioid use despite social and interpersonal negative consequences

- Decreased social or recreational activities

- Existing or increased difficulty fulfilling professional duties at school or work

- Excessive time is taken to obtain or recover from taking opioids

- Increased opioid consumption is present

- Opioid cravings occur

- Difficulty decreasing the frequency of using opioids

- Tolerance to opioids develops

- Opioid use continues despite the dangers it poses to the user

- Withdrawal occurs, or the user continues to take opioids to avoid withdrawal

The presence of 6 or more of these diagnostic criteria indicates severe OUD.

Providers can use validated screening tools such as:

- Urine and oral fluid toxicology testing

- Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST)

- Tobacco, Alcohol and/or other Substance use Tools (TAPS)

- A three-question version of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C)

The following patients are at higher risk for OUD or overdose:

- Depression or other mental health conditions

- History of a substance use disorder

- Loss of economic stability

- Social distress, such as relationship issues or housing concerns

- History of overdose

- Taking 50 or greater MME/day or taking other central nervous system depressants with opioids

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How often do you have patients exhibiting symptoms of OUD in your practice setting?

- What would your next steps be if you identify a patient with potential OUD (e.g., additional screening, referral, or treatment plans)?

- Have you noticed any trends in patients presenting with OUD? Such as socioeconomic status, occupation, gender, race, and medical diagnosis.

- Do you know how to determine if a patient is engaging in opioid-seeking behaviors?

CDC Guidelines

In 2022, the CDC updated the 2016 guidelines to help prescribers navigate prescribing opioids amid an epidemic.

These guidelines are directed toward prescribing medications to adults to be taken in the outpatient setting, for example, primary care clinics, surgery centers, urgent cares, and dental offices. These do not apply to providers caring for individuals with sickle-cell disease, cancer, those receiving inpatient care, or end-of-life or palliative care. They are also intended to serve as a guideline, and each treatment plan should be specific to the unique patient and circumstances (1).

Some of the Goals of the guidelines are to:

- Improve communication between providers and patients about treatment options and discuss the benefits and risks before initiating opioid therapy.

- Improve the effectiveness and safety of treatment to improve quality of life.

- Reduce risks associated with opioid treatment, including opioid use disorder (OUD), overdose, and death.

Recommendation #1 - Determining when it is appropriate to initiate opioids for pain (1).

An essential part of the prescribing process is determining the anticipated pain severity and duration based on the patient's diagnosis. Pain severity can be classified into three categories when measured using the standard 1-10 numeric scale. Pain scores 1-4 are considered mild, 5-6 are moderate, and 7-10 severe. Opioids are typically used for moderate to severe pain.

The patient's diagnosis will allow the provider to determine if pain initially falls into one of the following three categories of anticipated duration: acute, subacute, and chronic. Acute pain is expected to last for one month or less. Acute pain often is caused by injury, trauma, or medical treatments such as surgery. Unresolved acute pain may develop into subacute pain if not resolved in 1 month. If pain exceeds three months, it is classified as chronic. Pain persisting longer than three months is chronic. It can result from underlying medical conditions, injury, medical treatment, inflammation, or unknown cause.

The CDC guidelines state that non-pharmacologic and non-invasive methods are the preferred first-line method of analgesia, such as heat/cold therapy, physical therapy, massage, rest, or exercises, etc. Despite evidence supporting their use, these therapies are only sometimes covered by insurance, and access and cost can be barriers, particularly for uninsured persons who have limited resources, no reliable transportation or live in rural areas where treatments are not available.

When this is insufficient, non-opioid medications, such as Gabapentin, acetaminophen, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID), should be considered next. Selective antidepressants and anticonvulsant medications may also be effective. Some examples of when these drugs may be appropriate include neuropathic pain, lower back pain, musculoskeletal injuries (including minor pain related to fractures, sprains, strains, tendonitis, and bursitis), dental pain, postoperative pain, and kidney stone pain.

Providers, however, must also consider the risks and benefits of long-term NSAID use because it may also negatively affect a patient's gastrointestinal and cardiovascular system. Depending on the diagnosis, a patient may also require an invasive or surgical intervention to treat the underlying cause to alleviate pain.

If the patient has pain that does not sufficiently improve with these initial therapy regimens, at that point, opioids will be the next option to be considered.

It does not mean that patients should be required to sequentially "fail" nonpharmacologic and non-opioid pharmacologic therapy or use any specific treatment before proceeding to opioid therapy. Example: A patient for whom NSAIDs are contraindicated has recently sustained a rotator cuff injury and is experiencing moderate pain to the point at which it is disturbing their sleep, and it will be several weeks before they can have surgery.

Recommendation #2 - Discuss with the patient realistic treatment goals for pain and overall function (1).

Ideally, goals include improving quality of life and function, including social, emotional, and physical dimensions. The provider should help guide these patients to realistic expectations based on their diagnosis. This may mean that the patient may anticipate reduced pain levels but not complete elimination of pain.

The provider should discuss the expected or typical timeframe where they may need medications. If medications are anticipated for acute or subacute pain, a discussion about the expected timeframe for pain should be highlighted in the debate. The patient may then understand better if their recovery is progressing. For chronic conditions, the conversation will focus on or may emphasize the overall risks of beginning long-term medication therapy.

They may also advise patients, particularly those with irreversible impairment injuries, that they may experience reduced pain but will not regain function. An exit strategy will be discussed if opioid therapy is unsuccessful or the risk vs. benefit ratio is no longer balanced.

The second section of recommendations covers the selection of opioids and dosages.

Recommendation #3 - Prescribe immediate-release (I.R.) opioids instead of extended-release and long-acting (ER/LA) opioids when starting opioid therapy (1).

Immediate-release opioids have faster-acting medication with a shorter duration of pain-relieving action. ER/LA opioids should only be used in patients who have received specific dosages of immediate-release opioids daily for at least one week. Providers should reserve ER/LA opioids for severe, continuous pain, for example, individuals with cancer. ER/LA opioids should not be for PRN use.

The reason for this recommendation is to reduce the risk of overdose. A patient who does not feel adequate relief or relief fast enough from the ER/LA dose may be more inclined to take additional amounts sooner than recommended, leading to a potential overdose.

Recommendation #4 - Prescribe the lowest effective dose (1)

Dosing strategies include prescribing low doses and increasing doses in small increments. Prescribe the lowest dose for opioid patients. Carefully consider risk vs. benefits when increasing amounts for individuals with subacute and chronic pain who have developed tolerance. Providers should continue to optimize non-opioid therapies while continuing opioid therapy. It may include recommendations for taking non-opioid medications in addition to opioids and non-pharmacologic methods.

Providers should use caution and increase the dosage by the smallest practical amount, especially before increasing the total opioid dosage to 50 or greater morphine milligram equivalent (MME) daily. Increases beyond 50 MME/day are less likely to provide additional pain relief benefits. The greater the dosage increases, the tendency for risk also increases. Some states require providers to implement clinical protocols at specific dosage levels.

Recommendation #5 - Tapering opioids includes weighing the benefits and risks when changing the opioid dosage (1).

Providers should consider tapering to a reduced dosage or tapering and discontinuing therapy and discuss these approaches before initiating changes when:

- The patient requests dosage reduction or discontinuation,

- Pain improves and might indicate the resolution of an underlying cause,

- Therapy has not reduced pain or improved function,

- Treated with opioids for a long time (e.g., years), and the benefit-risk balance is not clear.

- Receiving higher opioid dosages without evidence of improvement.

- Side effects that diminish quality of life or cause impairment.

- Opioid misuse

- The patient experiences an overdose or severe event.

- Receiving medications or having a health condition may increase the risk of an adverse event.

Opioid therapy should not be discontinued abruptly unless there is a threat of a severe event, and providers should not rapidly reduce opioid dosages from higher dosages.

Patient agreement and interest in tapering will likely be a key component of successful tapers. Integrating behavioral and non-opioid treatment and interventions for comorbid mental health conditions before/during a taper can help manage pain, strengthen the therapeutic relationship between the provider and patient, and improve the likelihood of positive tapering outcomes.

When dosages are reduced or discontinued, a taper slow enough to reduce symptoms and withdrawal should be used. Patients should receive education on possible withdrawal symptoms and when to contact the provider.

For those taking opioids for a shorter duration, a 10% decrease of the original dose per week or slower until close to 30% of the initial amount is reached, followed by a weekly reduction of roughly 10% of the remaining dose) is less likely to trigger withdrawal. Tapers of 10% per month or less are better tolerated than rapidly tapering off when patients have been taking opioids for a longer duration (e.g., for a year or longer).

Significant opioid withdrawal symptoms can indicate the need to slow the taper rate further. Short-term medications might also help manage withdrawal symptoms. Providers should follow up frequently (at least monthly) with patients engaging in opioid tapering.

Close monitoring is required for patients who cannot taper and that continue on high-doses or otherwise high-risk opioid regimens and should work with patients to mitigate overdose risk. Some patients with unanticipated challenges to tapering may need to be evaluated for OUD.

The third section focuses on the duration of opioid therapy and routine patient follow-up.

Recommendation #6 - Prescribing no greater quantity than needed for the expected duration of severe pain requiring opioids (1)

A few days or less is often the length that opioids are used for common causes of nonsurgical acute pain. Many states have passed legislation that limits initial opioid prescriptions for acute pain to less than seven days. Many insurers and pharmacies have enacted similar policies. Providers should generally avoid prescribing additional opioids to patients if pain continues longer than expected.

Providers should prescribe and advise opioid use only as needed rather than on a scheduled basis (e.g., one tablet every 4 hours). Limiting the duration of therapy can decrease the need to taper. However, tapering may need to be considered if patients take these medications around the clock for more than a few days.

Longer durations of therapy may be needed when the injury is expected to result in prolonged severe pain (e.g., greater than seven days for severe traumatic injuries). Patients should be evaluated at least every two weeks if they are receiving opioids for acute pain. Suppose opioids are continued for a month or longer. In that case, providers should address potentially reversible causes of chronic pain so that the length of therapy does not continue to extend.

Recommendation #7 - Evaluate the benefits and harms of opioid therapy regularly (1)

The benefits and risks for Evaluating benefits and risks within 1-4 weeks of starting long-term opioid therapy for subacute and chronic pain should be evaluated within 1-4 weeks of initiating therapy and after dosage increases.

The evaluation should include patient perspectives on progress and challenges in moving toward treatment goals, including sustained improvement in pain and function. The Three-item Pain, Enjoyment of Life, and General Activity (PEG) assessment scale could be utilized to help determine patient progress.

Providers should also ask patients about common adverse effects, such as constipation and drowsiness, and assess for outcomes that might be early warning signs for more serious problems such as overdose or OUD.

Patient re-evaluation should occur after therapy begins (about two weeks) when ER/LA opioids are prescribed if the total daily opioid dosage is greater than or equal to 50 MME/day or if there is a concurrent benzodiazepine prescription. These individuals are at a higher risk for overdose. Follow-up for individuals starting or increasing the dosage of methadone is recommended every 2-3 days for the first week. Providers should reassess all patients receiving long-term opioid therapy at least every three months.

The last section of recommendations covers patients at risk for OUD and overdose.

Recommendation #8 - Use strategies to mitigate risk by evaluating risk for opioid-related harms, discussing risk with patients, and incorporating risk reduction strategies into the treatment plan (1).

The patient's habits (including alcohol and illicit drug use) and behavioral and mental health must be considered. Patients with a history of substance use disorders, depression, and/or mental health disorders have a higher risk of overdose and OUD. Even though the dangers of opioid therapy are higher with these patients, they may still require opioid treatment for pain management.

Psychological distress can interfere with improvement of pain and/or function in patients experiencing chronic pain; using tools like the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)-7 and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 or PHQ-4) to assess for anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and depression might help providers improve overall pain treatment outcomes. They should also ensure that treatment for depression and other mental health conditions is effective, consulting with behavioral health specialists when needed.

Additionally, providers should:

- Educate on the risks for overdose when opioids are combined with other drugs or alcohol.

- Use caution when prescribing opioids for people with sleep-disordered breathing due to their increased risk for respiratory depression. The provider may ascertain if a patient is compliant with prescribed CPAP.

- Use caution and increased monitoring for patients with renal or hepatic insufficiency.

- Use caution and increased monitoring for patients aged 65 years or older.

- Offering naloxone when prescribing opioids, particularly to patients at increased risk for overdose.

If patients experience a nonfatal opioid overdose, providers should evaluate for OUD. Providers should reduce opioid dosage and discontinue opioids when indicated and continue monitoring and support for patients prescribed or not prescribed opioids.

Recommendation #9 - Reviewing Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) data (1).

Providers should review PDMP data specifically for prescription opioids, benzodiazepines, and other controlled medications patients have received from additional prescribers to determine all the opioids the patient could potentially receive.

Patients with multiple prescriptions and from various providers are at an increased risk for overdose or OUD. PDMP data should be reviewed before initial drugs for subacute or chronic pain and at least every three months during long-term opioid therapy.

Recommendation # 10 - Considering the benefits and risks of [urine] toxicology testing.

Toxicology testing should be used to inform and improve patient care. Providers, practices, and health systems should minimize bias in testing and not test based on assumptions about different patients.

Recommendation # 11 - Use caution when prescribing opioid pain medication and other medications concurrently (1).

Benzodiazepines and opioids can cause CNS depression and potentiate opioid-induced decreases in respiratory drive. Because other CNS depressants can potentiate respiratory depression associated with opioids, benefits vs. risks should be considered.

Recommendation # 12 - Offering or arranging treatment for OUD if needed (1).

Includes referring a patient to a specific treatment center where behavior therapy and medications may be prescribed.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How often do you have patients exhibiting symptoms of OUD in your practice setting?

- What would your next steps be if you identify a patient with potential OUD (e.g., additional screening, referral, or treatment plans)?

- Have you noticed any trends in patients presenting with OUD? Such as socioeconomic status, occupation, gender, race, and medical diagnosis.

- Do you know how to determine if a patient is engaging in opioid-seeking behaviors?

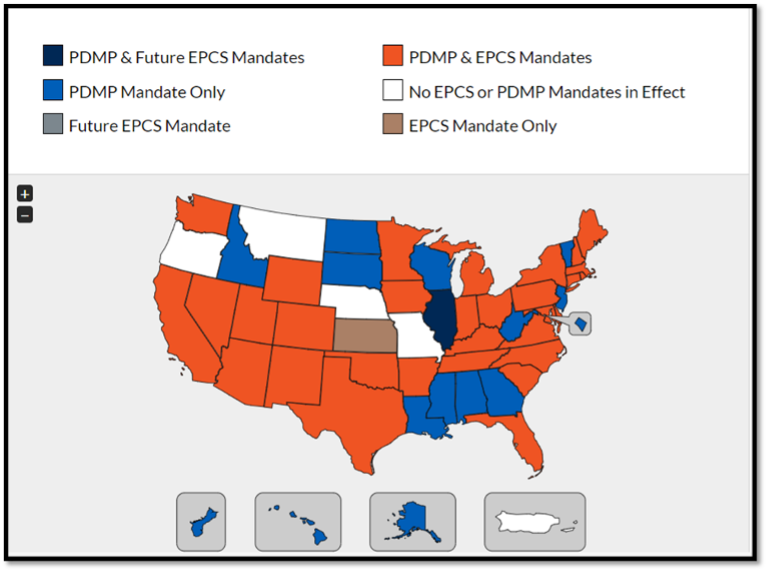

Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMP) and Electronic Prescribing

PDMP is a database that keeps track of controlled substance prescriptions. They help improve opioid prescribing, inform clinical practice, and protect at-risk patients. A pharmacist must enter controlled substances into the state PDMP when dispensing them. When the pharmacist enters this data, it may occur at various intervals, from 1 month, daily, or even "real-time." However, a PDMP is only helpful if providers check the system before prescribing (10).

Some states have implemented legislation that requires providers to check a state PDMP before prescribing certain controlled substances and in certain circumstances. Most current mandates require that all prescribers query PDMPs when prescribing any opioid.

Some states require prescribers to query PDMPs every time a controlled substance is prescribed, while others require a query only for the initial prescription. Subsequent checks of PDMPs also vary from every time a drug is issued to specific intervals (e.g., every 90 days, twice a year, annually) should prescribing continue. Some mandates have categorical requirements, e.g., a query must be made if the prescription is over a three-day or seven-day supply or if a certain prescribed level of MME is exceeded.

Other states' mandates are based on subjective criteria, e.g., a prescriber's judgment of possible inappropriate use or the prescriber's discretion regarding whether to query the PDMP. Finally, some states mandate that only prescribers in opioid treatment programs, workers' compensation programs, or pain clinics must query PDMPs (10, 11).

In addition to PDMPs, there has been an increase in requirements for providers to utilize Electronic Prescribing for Controlled Substances (ECPS). Electronic prescribing programs for both providers and pharmacies must meet DEA requirements. The DEA's March 31, 2010, conditions were updated on July 27, 2023 (12).

On January 1, 2023, CMS implemented additional requirements for controlled substances for recipients of Medicare Part D. There are over 51 million U.S. people enrolled in Medicare Part D (Center for Medicare Advocacy, 2023). In addition to state laws, these rules require that prescribers e-prescribe at least 70 percent of controlled substances for patients that have Medicare Part D. A waiver may be approved if the prescriber cannot conduct electronic prescribing due to circumstances beyond the provider's control (12).

Starting June 27, 2023, the 'Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023' requires new or renewing Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) registrants, to have at least one of the following:

- A total of eight hours of training from specific organizations on opioid or other substance use disorders.

- Board certification in addiction medicine or addiction psychiatry from the American Board of Medical Specialties, American Board of Addiction Medicine, or the American Osteopathic Association.

- Graduation within five years and status in good standing from medical, advanced practice nursing, or physician assistant school in the U.S. that included an opioid or other substance use disorder curriculum of at least eight hours (11,12).

Providers must follow either state law or DEA/CMS regulations, whichever is more stringent. The following map indicates various rules in each state, which will continue to change when new legislation is enacted (11,12).

(11)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are the laws in your state about PDMP and EPCS?

- What references can you refer to find out prescribing laws in your state?

- Is the use of PDMP a common practice in your workplace?

Opioid Storage and Disposal

Prescription opioids need to be stored securely. It may include the necessity of keeping them in a locked area. This is especially true if children, teens, and other visitors in the house may be aware of their presence.

Teens and young adults are the biggest misusers of prescription pain medication. In 2018, over 695,000 youths ages 12–17 and 1.9 million young adults ages 18–25 reported misusing prescription pain medication in the past year. Young people may misuse prescription opioids for many reasons, including curiosity, peer pressure, and wanting to fit in. Another reason teens and young adults may decide to take prescription opioids is because they can be easier to get than other drugs.

Studies show that 53% percent of people over 12 who obtained prescription pain medication for non-medical use received them from a friend or relative (13).

Patients should be advised on how to get rid of unused or expired medications. The best option is to immediately take them to a drug take-back site, location, or program. These sites or programs can be found online, or the pharmacist may have information.

If it is not feasible for the patient to get rid of the drug using a take-back program, the patient should be advised to check if it is on the FDA flush list. If it is, the medication should be flushed down the toilet. Again, the list of drugs is available on the FDA website. If it is not on that list, it should be discarded in the trash at home.

Patients should follow the following instructions: Mix medicines (liquid or pills; do not crush tablets or capsules) with an unappealing substance such as dirt, cat litter, or used coffee grounds. Next, place the mixture in a container such as a sealed plastic bag; then throw away the container in your trash at home. Last, the patient should remove or permanently cover all personal information on the prescription label of empty medicine bottles or packaging, then trash or recycle the open container (14).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Do you often teach your patients about the safe storage and disposal of opioids? If not, what are some barriers to providing this education? How could you overcome these barriers?

- Your patient asks if they can give the leftover pills to their spouse, who has back pain; what would be an appropriate response?

- The patient replies that it is the same medication their spouse has been prescribed and doesn't understand why they can't share it; what education will you provide?

OUD Treatment

Treatment for OUD is multi-faceted and typically includes both mental health components and FDA-approved OUD treatment medications. Mental health components may consist of counseling or a structured treatment program. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) may also be beneficial.

A potential barrier to OUD treatment, on the provider's and patient's behalf, is the perception that patients must engage in counseling to start or continue receiving OUD treatment medication. While the mental health components are essential, there may be barriers for patients to begin mental health treatment programs, which include expense, travel, and available openings within the programs.

Medication therapy may be a helpful start for these patients (9). FDA-approved medications indicated for the treatment of OUD include methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Suboxone is a combination drug composed of buprenorphine and naltrexone.

Medication has several advantages as part of the OUD treatment plan:

- Help the individual to remain safe and comfortable during detox.

- Reduce or eliminate cravings for opioids.

- Minimize relapse since the individual is not experiencing uncomfortable withdrawal symptoms.

- Allow the individual to focus on therapy without being distracted by withdrawal symptoms and cravings.

- Increase safety in cases of overdose.

Methadone

Methadone is a fully agonistic opioid. It is a Schedule II controlled medication. It can be prescribed purely for the treatment of pain, as well as for OUD. Methadone treatment for OUD can only be provided through a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services (SAMHSA)-certified opioid treatment program.

Patients taking methadone to treat OUD must receive the medication under the supervision of a clinician. After consistent compliance, patients may take methadone at home between program visits. The length of methadone treatment should be a minimum of 12 months. Methadone doses are often adjusted and readjusted. Methadone is slowly excreted, and there is overdose potential if not taken as prescribed (9).

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is a partial agonist opioid. Buprenorphine can be prescribed by any provider with a current, standard DEA registration as a Schedule III Controlled Substance. Like opioids, it produces effects such as euphoria or respiratory depression. With buprenorphine, however, these effects are weaker than those of full opioids such as heroin and methadone. It also has unique pharmacological properties that help lower the potential for misuse and diminish the effects of physical dependency opioids, such as withdrawal symptoms and cravings (9).

Subutex was a brand-name version of buprenorphine, discontinued in 2011 after new formulations that were less likely to be abused were developed.

Naltrexone

Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist. It is not addictive and does not cause withdrawal symptoms. It blocks the euphoric and sedative effects of opioids by binding and blocking opioid receptors and reduces and suppresses opioid cravings.

There is no abuse and diversion potential. Naltrexone can be prescribed in any setting. It can be taken as a pill or once monthly extended-release intramuscular injection (9).

It was estimated 2021 that of the 2.5 million people with OUD, only 36% received any treatment, and only 22% received medications. A part of the July 27, 2023, Consolidated Appropriations Act amended the Controlled Substances Act to eliminate the requirement that providers obtain a specific waiver (a DATA waiver) to prescribe buprenorphine (including Suboxone) to treat opioid use disorder, known as the X-waiver.

Additionally, there are no longer any caps on the number of patients a practitioner can treat. This, however, does not change the requirements for methadone treatment (15).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Will the recent DEA changes enhance your ability to treat patients with OUD?

- What are some other barriers to identifying and treating patients with OUD?

Nursing Considerations

What Is the Nurses' Role in Opioid Patient Education and Opioid Medication Management?

Nurses remain the most trusted profession for a reason, and APRNs are often pillars of patient care in several health care settings. Patients turn to nurses for guidance, education, and support.

While there are no specific guidelines for the nurses' role in opioid education and management, here are some suggestions to provide quality care for patients currently taking opioid medications.

- Take a detailed health history. Often times, pain, and mental health, can be dismissed and overlooked in health care settings. If a patient is complaining of symptoms that could be related to pain, inquire more about that complaint. Ask about how long the symptoms have lasted, what treatments have been tried, if these symptoms interfere with their quality of life, and if anything alleviates any of these symptoms.

If you feel like a patient's complaint is not being taken seriously by other health care professionals, advocate for that patient to the best of your abilities. A detailed pain assessment and history can provide context for opioid pain management and a patient's plan of care. When taking a health history, ask about any prior surgeries, major life stressors in the past year, or any prior opioid usage.

- Review medication history at every encounter. Often times, in busy clinical settings, reviewing health records can be overwhelming. Millions of people take pain medications, including opioids, for various reasons. Ask patients how they are feeling on the medication, if their symptoms are improving, if there are any changes to medication history, if they use any other substances other than prescribed medications, such as alcohol, tobacco, or other drug use.

Remember, prescription medications are not the only medications people take. Confirm medication route, dosage, frequency, and all the details to make sure you and the patient are on the same page and to avoid medication errors and complications.

- Be willing to answer questions about pain, mental health, and opioid medication options. Society stigmatizes open discussions of prescription medication and pain. Sometimes, people are afraid of asking for pain medication for perception of being a "drug seeking" patient without having their pain concerns addressed. Other times, there are patients who might have OUD and continuously ask for an increased number of opioid medications.

Be willing to be honest with yourself about your comfort level discussing topics and providing education on opioid medications, drug interactions, and pain management.

- Communicate the care plan to other staff involved for continuity of care. For several patients, especially for patients with chronic pain or who use opioids long-term, care often involves a team of mental health professionals, physical therapists, nurses, specialists, pharmacies, and more. Ensure that patients' records are up to date for ease in record sharing and continuity of care and to reduce the incidence of opioid medication errors.

- Stay up to date on continuing education related to opioid medications, pain management, and prescribing regulations. Evidence-based information and scope of practice is always evolving and changing. You can then present your new learnings and findings to other health care professionals and educate your patients with the latest information.

You can learn more about the latest research on pain management medications, non-pharmacological pain management options, and opioids by following updates from evidence-based organizations, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or your local health department.

How can nurses identify if someone is in pain?

Unfortunately, it is not possible to look at someone with the naked eye and determine if they are in pain. Sometimes, a patient in pain will be very obvious with visible lacerations and need pain management options, such as opioids. Other times, pain management is often done as a result by taking a complete health history, listening to patient's concerns, completing a pain assessment, and offering testing to determine the cause of pain.

How can nurses identify if someone has OUD?

Unfortunately, it is not possible to look at someone with the naked eye and determine if they have OUD. Sometimes, a patient in pain will be very obvious with visible withdrawal symptoms, such as asking for more opioid medications or discussing symptoms of OUD. Often times, OUD is diagnosed and recognized as a result by taking a complete health history, listening to patient's concerns, and offering testing to determine the cause of pain. Remember, anyone can have OUD, and no two OUD patients appear the same.

What should patients know about opioid medication?

Patients should know that anyone has the possibility of experiencing side effects on opioid medications, just like any other medication. Patients should be aware that if they notice any changes in their breathing, changes in their heart rate, or feel like something is a concern, they should seek medical care.

Because of the social stigma associated with opioids and pain management, people are hesitant to seek medical care because of fear, shame, and embarrassment. However, as more research and social movements discuss opioid use, there is more space and awareness for opioid education and opioid overdose prevention.

Nurses should also teach patients to advocate for their own health in order to avoid possible opioid complications or not have their pain be poorly managed.

Here are important tips for patient education in the inpatient or outpatient setting:

- Tell the health care provider of any existing medical conditions or concerns (need to identify risk factors)

- Tell the health care provider of any existing lifestyle concerns, such as alcohol use, other drug use, sleeping habits, diet, menstrual cycle changes (need to identify lifestyle factors that can influence opioid use and pain management)

- Tell the health care provider of any prior experiences with opioid medication (if applicable) and any medication reactions or side-effects you remember (need to identify risk factors, address pain management appropriately, identify any allergies, and avoid possible opioid overdose symptoms)

- Tell the health care provider if you have any changes in your breathing, bodily functions, or heart rate (potential opioid overdose symptoms)

- Tell the nurse of health care provider if you experience any pain that increasingly becomes more severe or interferes with your quality of life

- Keep track of your pain, overall health, medication use, and health concerns via an app, diary, or journal (self-monitoring for any changes)

- Tell the health care provider right away if you are having thoughts of hurting yourself or others (possible increased risk of suicidality and public safety concerns)

- Take all prescribed medications as indicated and ask questions about medications and possible other treatment options, such as non-pharmacological options or surgeries

- Tell the health care provider if you notice any changes while taking medications or on other treatments to manage your pain (potential worsening or improving health situation)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some problems that can occur if opioid medications are not managing pain adequately?

- What are some possible ways you can obtain a detailed, patient centric health history?

- What are some possible ways APRNs can educate patients on pain and opioid medication options?

Research Findings

What Research on Opioid Medication Exists Presently?

There is extensive publicly available literature on opioids medications via the National Institutes of Health and other evidence-based journals.

What are some ways for people who take opioids to become a part of research?

If a patient is interested in participating in clinical trial research, they can seek more information on clinical trials from local universities and health care organizations.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

What are some reasons someone would want to enroll in clinical trials?

New Jersey Safe Prescribing for Opioids for APRNs

APRNs in New Jersey can obtain prescriptive authority for controlled substances from the New Jersey Division of Consumer Affairs' Drug Control Unit. APRNs need to obtain federal Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) controlled substance registration and then apply for a New Jersey Controlled Drug Substance (CDS) registration (16, 17).

N.J. Admin. Code § 13:37-7.9 provides an overview for the prescriptive practice of APRNs (18). Questions regarding the scope of practice for APRNs and controlled substances can be addressed to the New Jersey Division of Consumer Affairs directly (17).

Conclusion

Even providers who do not prescribe opioids should be familiar with the effects of opioids and OUD due to its high prevalence in the United States. Understanding the types of pain, how pain occurs, and how it impacts a person's quality of life is especially important. There is still an associated stigma among patients who use Opioids to treat chronic pain conditions. It is essential to recognize that there are times when opioid use is appropriate, as long as the provider practices the recommended guidelines and sound clinical judgment.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

What other measures would help decrease the opioid epidemic in the United States?

Case Study #1:

Patient Name: John Henderson

Gender: Male

Age: 60

Height: 6' 1"

Weight: 190 lbs.

John arrives at the primary care office after work for a routine office visit. He is employed as a grocery store manager. He reports he does not use tobacco and has never used tobacco. He reports that he drinks alcohol a few times a week and reports no illicit drug use. He has hypertension and high cholesterol and takes Losartan 50mg daily and Atorvastatin 20 mg daily. He reports that he does not have a blood pressure monitor, but sometimes checks his blood pressure after work at the grocery store pharmacy.

This patient presents to a primary care office with pain and stiffness in the right shoulder joint, which has progressively worsened for six months following rotator cuff surgery. He states his pain is unchanged, and he has a limited range of motion in the right shoulder that is getting worse. Now, for the past few weeks, the pain has started to interfere with his ability to do his job. He said he went to physical therapy for a few weeks after his surgery, but admitted he did not often complete the home exercise program regimen. An MRI was obtained and showed he had adhesive capsulitis.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some specific questions you'd want to ask about shoulder pain?

- What is some health history questions you'd want to highlight?

- What lab work or testing would you suggest performing?

- What are some assessments you can do in-office to check his shoulder's range of motion?

When you assessed his right shoulder compared to the left shoulder, there was a noticeable difference between the two. John was also visibly in pain after the right shoulder assessment.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some non-pharmacological interventions you can do for John's shoulder?

- What pain assessments would you perform on John?

After assessing John's shoulder and completing a few pain assessments, John asked about opioids. John is interested in learning more, but he states he "doesn't wany any crazy side effects because of my work and family life." He states that he also doesn't want "to end up a junkie on drugs" and wants to know if he can drink alcohol still and take his other medications while on opioids. John also wants to know if he will have to take opioids forever like the other medications he's taking.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are opioid-drug interactions to consider with John's existing medication history and alcohol use?

- What are some possible side effects of opioids?

- What are some possible long-term effects of chronic opioid use?

- What are some interventions to consider prior to prescribing opioids?

Given the patient's diagnosis, non-opioid therapy options include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, intraarticular glucocorticoid injections, steroid injections into the shoulder joint, range of motion exercises, physical therapy, and consulting with an orthopedic specialist who may recommend a joint manipulation under anesthesia. Each of these should be considered before opioid therapy.

Case Study #2:

Patient Name: Pilar Aguilar

Age: 40

Height: 5' 1"

Weight: 135 lbs.

She reports that she does not smoke, drink alcohol, or take illicit substances. She reports experiencing a hip injury following a car accident three years ago and developed chronic post-traumatic arthritis in the hip. After a total hip arthroplasty, she was diagnosed with heterotopic ossification (HO).

For the past year, she has been taking 20 mg of oxycodone twice daily to manage chronic hip pain after unsuccessful non-opioid therapies. She has three children with no known pregnancy or postpartum complications. She previously worked part-time as an administrative assistant but has been off work since a car accident three years ago. She has PTSD related to this car accident. She has been prescribed Xanax 0.5mg up to three times daily for anxiety.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some specific questions you'd want to ask about hip arthritis?

- What are health history questions you'd want to highlight?

- What lab work or testing would you suggest performing?

The patient was present at an urgent care clinic today, complaining of a severe migraine, which started yesterday. She stated she needed to take more of her oxycodone to deal with the pain and because she could not sleep last night. She is concerned because she is running out of pills. She said her primary care doctor's office was closed, so she came to the urgent care. The following strategies would be an appropriate course of action for this patient:

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some non-pharmacological interventions you can do for Pilar's pain?

- What are some questions you'd want to ask about her migraine?

- What are some possible side effects of opioid use would you discuss with her?

Here are some things to consider for Case Study #2:

- Discuss concerns with the patient. This includes taking the opioid more often than prescribed, potential problems with respiratory depression, and overdose.

- Recommend trying eletriptan or dihydroergotamine nasal spray first rather than additional opioids.

- Review the PDMP to see the prescription history for this patient. Attempt to contact the primary care provider to develop a plan of care.

- Consider conducting toxicology testing

- Consider offering naloxone

- Use the DSM-5 criteria to assess the presence (and severity) of OUD or arrange an assessment with a substance use disorder specialist. Offer treatment for OUD if it is confirmed.

Case Study #3

Sabrina is a 16-year-old Black high school student working as a waitress at a local restaurant. She arrives at the local pediatric emergency room after her shift with her mom because she thinks she is experiencing a sickle cell crisis.

Sabrina reports that she has these crises every few months, and this is probably the third time she's been in this much pain. She reports being at this ER last year for something similar. Her mother is there completing paperwork and would like Sabrina to get some pain medication as well.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some specific questions you would want to ask about her health?

- What are health history questions you would want to highlight?

- What lab work or testing would you suggest performing?

- What pain assessments would you perform on Sabrina?

Sabrina agrees to provide bloodwork, complete imaging, and be admitted. She said that no health care provider talked to her about how painful sickle cell crises can be, and she doesn't routinely take pain medication because she "doesn't want to be addicted." Sabrina and her mom heard about pain management options for these extremely painful episodes from social media and the Internet and would like Sabrina to get her pain controlled. Sabrina said that she had some opioid last time she was in the ER, but she doesn't remember the name. Her mom doesn't remember the name either, but she remembers it was in an IV.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How would you discuss Sabrina's pain management concerns?

- Given Sabrina's age, medical history, and prior history of opioid use, what medication options would be appropriate for a sickle cell crisis in an adolescent?

Sabrina has been in the pediatric ER for over a day receiving IV hydromorphone. She reports some relief, but Sabrina and her mom are concerned. Sabrina wants to live her life like a normal teenager without being in the hospital every few months for pain.

Her mom asks if there is a way to have pain medication at home. Both Sabrina and her mom would like to know if there is anything that can be done to help with the pain outside of medications as well. Sabrina doesn't want to use pain medications daily but wants to have them at home just in case she can't get to the hospital.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Knowing Sabrina's concerns, what are some possible non-pharmacological pain management options?

- Knowing Sabrina's health history, what would be some patient education talking points about at-home opioid medications and possible side effects?

- What are some possible consequences of leaving pain improperly managed?

New Jersey Implicit and Explicit Bias

Introduction

In OB-GYN care, biases—both implicit and explicit—can affect pain management during labor, the interpretation of patient concerns, and treatment decisions based on factors such as race, ethnicity, weight, age, or sexual orientation [1]. These biases contribute to disparities in care and can result in negative health outcomes [1]. Implicit bias stems from unconscious stereotypes, while explicit bias involves expressed discriminatory attitudes [2].

The presence of both explicit and implicit biases among maternity care providers plays a significant role in creating disparities in person-centered maternity care (PCMC) [3]. These biases can influence providers' perceptions and behaviors, leading to unequal treatment of pregnant persons during childbirth. Individuals of lower socioeconomic status (SES) often experience less dignified, less responsive care compared to those of higher SES, perpetuating healthcare inequalities [4]. Understanding the impact of these biases is crucial for addressing disparities in PCMC and ensuring that all pregnant persons receive respectful, responsive care regardless of their socioeconomic background. Implicit bias often leads to associating high socioeconomic status (SES) with positive patient traits and low SES with negative ones, contributing to inequities in the quality of care provided [5].

PCMC, defined as respectful and responsive care that honors the preferences, needs, and values of pregnant person during childbirth, has gained prominence in global health discussions [6]. Despite this focus, PCMC remains suboptimal, with significant disparities based on SES. Pregnant persons of lower SES tend to experience poorer PCMC, characterized by less dignified treatment, ineffective communication, and diminished respect for autonomy, compared to pregnant person of higher SES [7]. Disrespectful and non-responsive care, common in facility-based childbirth, deters pregnant persons from seeking institutional care, which can affect maternal and neonatal health outcomes.

Positive PCMC experiences lead to improved outcomes, including increased patient engagement, trust, satisfaction, and stronger psychosocial health [8]. Studies have demonstrated that essential components of PCMC, including birth companionship and respectful communication, are associated with favorable clinical outcomes like shorter labor duration and lower rates of cesarean deliveries [9]. Disrespectful treatment and assumptions about the cognitive abilities or cooperation of low SES pregnant person perpetuate negative healthcare experiences and reinforce community mistrust of facility-based childbirth services [3].

Both explicit and implicit biases shape these care disparities. Explicit bias reflects conscious negative attitudes or beliefs toward certain groups [2]. Implicit bias influences behavior through quick, automatic associations triggered by characteristics like appearance or SES [2].

While much of the research on healthcare provider bias has focused on racial disparities, SES bias is relevant in contexts where racial distinctions are less pronounced. In the United States, many perceive low-SES patients as less intelligent, compliant, or engaged in their health, leading to poorer care, shorter consultations, and fewer diagnostic tests [4][10]. Patients report feeling the impact of SES bias through perceived discrimination and lower quality interactions with healthcare professionals, contributing to mistrust and poorer health outcomes over time [1][4].

These outcomes emphasize the need to address both forms of bias through targeted interventions aimed at improving PCMC is those with a lower SES. Improving provider awareness and enhancing communication, respect, and responsiveness in care delivery are critical steps in reducing disparities and improving health outcomes for all pregnant persons [11].

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How might implicit and explicit biases influence the perceptions and behaviors of maternity care providers toward pregnant persons of different socioeconomic statuses?

- In what ways can biases based on socioeconomic status contribute to disparities in person-centered maternity care and affect maternal and neonatal health outcomes?

- Why is it important to address both implicit and explicit biases when aiming to improve respectful and responsive care for all pregnant persons?

- How can understanding the role of socioeconomic status in healthcare biases help in developing interventions to reduce disparities in maternity care?

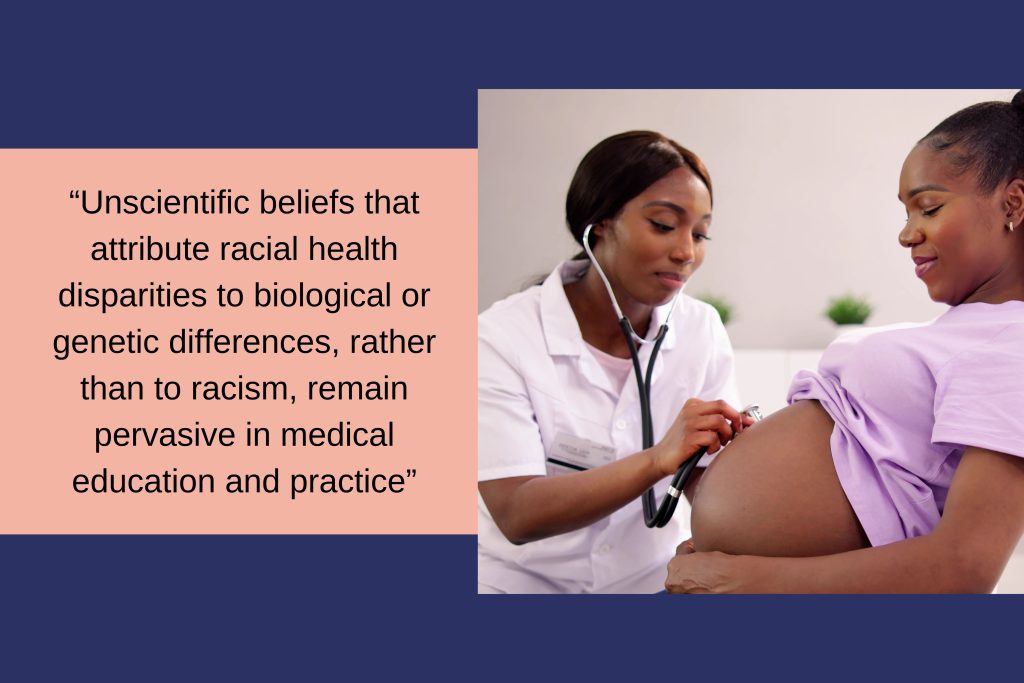

Bias and Stereotyping in Healthcare

Unscientific beliefs that attribute racial health disparities to biological or genetic differences, rather than to racism, remain pervasive in medical education and practice [12]. These misconceptions, often left unchallenged at the institutional level, infiltrates treatment decisions involving race, and this harms outcomes. For instance, medical students and residents who held explicit stereotypes about Black individuals being of biological difference made less accurate pain management decisions for Black patients [13].

Within the field of obstetrics and gynecology there are significant and perpetuating such stereotypes. The unethical experiments conducted by early gynecologists like J. Marion Sims and François Marie Prevost on enslaved women, including Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsy, while resulting in advances such as vesicovaginal fistula repair and cesarean delivery, contributed to harmful racial stereotypes [14]. These experiments fostered the false belief that Black pregnant persons have a higher tolerance for pain, a stereotype that persists today and may explain why Black pregnant persons may receive epidural analgesia at a reduced rate during labor or postpartum opioids, even when pain levels are comparable [14].

This belief continues to influence modern obstetric tools and decision-making processes. The Vaginal Birth After Cesarean (VBAC) success calculator is a tool to estimate the likelihood of a successful vaginal delivery after a previous cesarean section [15]. The calculator incorporates several factors, including maternal age, body mass index (BMI), prior vaginal delivery, and notably, race or ethnicity. As a result, well-meaning clinicians practicing evidence-based medicine may provide differing counseling to White and Black patients. For instance, the calculator might predict a 66.1% chance of successful VBAC for a White woman but only 49.9% for a Black woman with identical clinical characteristics [12]. This race-based counseling can lead to different decisions—where a White woman may pursue a trial of labor, a Black woman may opt for cesarean delivery, thus contributing to unnecessary maternal morbidity and exacerbating racial disparities in healthcare.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What might be the underlying reasons that unscientific beliefs attributing racial health disparities to biological differences persist in medical education and practice?

- In what ways have historical unethical medical practices on enslaved women influenced current stereotypes and treatment approaches in obstetrics and gynecology?

- How does the use of race or ethnicity in tools like the VBAC success calculator affect clinical counseling, and what are the potential implications for racial disparities in healthcare outcomes?

Transformations in Care Delivery

The use of standardized protocols can enhance outcomes and address disparities [16]. In California, hospitals implemented a hemorrhage quality improvement collaborative that reduced Black–White disparities in severe maternal morbidity [17]. A labor induction protocol reduced racial disparities in cesarean deliveries and neonatal morbidity [28]. However, standardized protocols may also contribute to disparities. A California hospital implemented a prenatal substance use reporting protocol to child protective services, causing reports of Black mothers to occur five times more often than reports of White mothers during the study period [12]. This outcome resulted from the policy. Standardized quality improvement protocols can worsen disparities across care settings because health systems serving vulnerable populations lack sufficient resources to implement these initiatives [29].

It is important to invest in initiatives aimed at reducing Black–White maternal health disparities and to pilot test them before wide-scale implementation to prevent exacerbating inequalities. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' support of the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act of 2021 shows how medical professionals can direct resources to underfunded healthcare systems that serve Black women, ensuring they have the necessary tools to implement and monitor quality improvements [18].

Furthermore, patients of all backgrounds should receive care based on clinical guidelines supported by reliable data. Such care can reduce or even eliminate racial disparities in certain health outcomes, as seen in ovarian cancer survival rates [19]. The Research Working Group of the Black Mamas Matter Alliance developed a research framework to ensure that Black pregnant persons participate in research teams and studies [20].

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How might standardized protocols both reduce and contribute to healthcare disparities in maternal health?

- What factors and practices prevent standardized initiatives from exacerbating inequalities in vulnerable populations?

- Why is it important to pilot test health interventions before implementing them on a wide scale, especially concerning racial disparities?

- How does involving Black pregnant persons in research teams and studies contribute to more equitable healthcare outcomes?

Framework for Addressing Implicit and Explicit Bias in Maternity Care

Curriculum Design with Antiracism and Social Justice Foundations

Develop an educational framework rooted in antiracism and social justice theories. This equips learners to recognize and challenge practices within the field of care.

Bias Awareness and Management Training

Incorporate training on recognizing and managing bias throughout the curriculum. This training should focus on both implicit and explicit biases, helping healthcare providers understand their impact on patient care and outcomes.

Removal of Stereotypical Patient Descriptions

Eliminate stereotypical patient descriptions from all syllabi, case studies, and examination materials. This prevents the reinforcement of harmful biases in the learning environment and promotes equitable care for all patients.

Critical Analysis of Epidemiology and Evidence-Based Medicine

Encourage critical review of epidemiology and evidence-based medicine to identify and address assumptions rooted in discriminatory practices or structural racism. This ensures that medical knowledge does not unintentionally perpetuate stereotypes and biases.

Competency-Based Education and Holistic Evaluations

Adopt competency-based medical education and holistic evaluation methods to reduce bias in the assessment of learners. This approach emphasizes skills and knowledge over factors that bias may influence, promoting fairness in evaluation and advancement.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How can integrating antiracism and social justice theories into medical education help learners recognize and challenge existing practices in healthcare?

- What effects might removing stereotypical patient descriptions from educational materials have on the delivery of equitable patient care?

Strategies for Addressing Implicit Bias in Healthcare

To address health inequities, many U.S. states have considered or enacted laws requiring implicit bias training (IBT) for healthcare providers. California's "Dignity in Pregnancy and Childbirth Act" mandates that hospitals and birth centers offer IBT to perinatal clinicians to improve outcomes for Black pregnant persons and birthing people [21]. Gathering insights from IBT stakeholders is essential for shaping policy, developing curricula, and guiding implementation efforts.

Education on implicit bias and strategies for managing its impact should be a core component of broader health system efforts to standardize knowledge on recognizing and addressing bias. Research conducted by the Center for Health Workforce Studies at the University of Washington School of Medicine evaluated the effectiveness of a brief online course on implicit bias in clinical and educational settings. The study found that the course increased bias awareness among a national sample of academic clinicians, regardless of their personal characteristics, practice setting, or the level of their implicit racial and gender-based biases [22].

Public policy plays a key role in addressing bias in medical care and promoting racial diversity in the perinatal workforce. The federal government also plays a crucial role in addressing discrimination in healthcare. The Office of Civil Rights conducts Title VI investigations into allegations of discrimination within organizations receiving funding [23]. Legal and healthcare experts have suggested reforms to Title VI to extend these investigations to include all physician-provided services. This helps increase trust among patients, promotes diligence among physicians, and works to reduce disparities in treatment.

Beyond raising awareness, clinicians can take concrete steps to manage the impact of implicit bias in patient care. Act by engaging in role modeling; participate in training to address and interrupt microaggressions and behaviors; and undergo training to eliminate descriptions in notes and communications. Teaching faculty at academic medical centers can contribute by developing inclusive curricular materials that feature diverse imagery and examples, and by consistently using inclusive language in all forms of communication.

At the organizational level, the foundation of bias-management efforts should be a comprehensive, ongoing diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) education program [24]. This program should focus on interactive, skill-building education that addresses implicit bias recognition and management and should involve all employees and trainees across the healthcare system. Organizations should also collect data to track equity and monitor progress and adopt best practices for increasing workforce diversity and integrate antibias education and practices into their professionalism policies. Policies for hiring, performance review, and promotion should also give weight to candidates’ DEI contributions.

Reporting systems can further institutional efforts to manage bias. Incident-response teams can review incidents, gather information, and either refer the matter to a department, such as human resources, or conduct further investigation. Transparency is key to the process, and reporting on bias incidents, detailing affected groups, locations, and common themes. The four high-priority areas for intervention: bias in pain management, responses to microaggressions and implicit bias, biased behaviors from patients toward medical staff, and opportunities for enhancing institutional inclusivity [25]. By implementing similar strategies, both individuals and organizations can take meaningful steps toward reducing bias and promoting equity in healthcare settings.

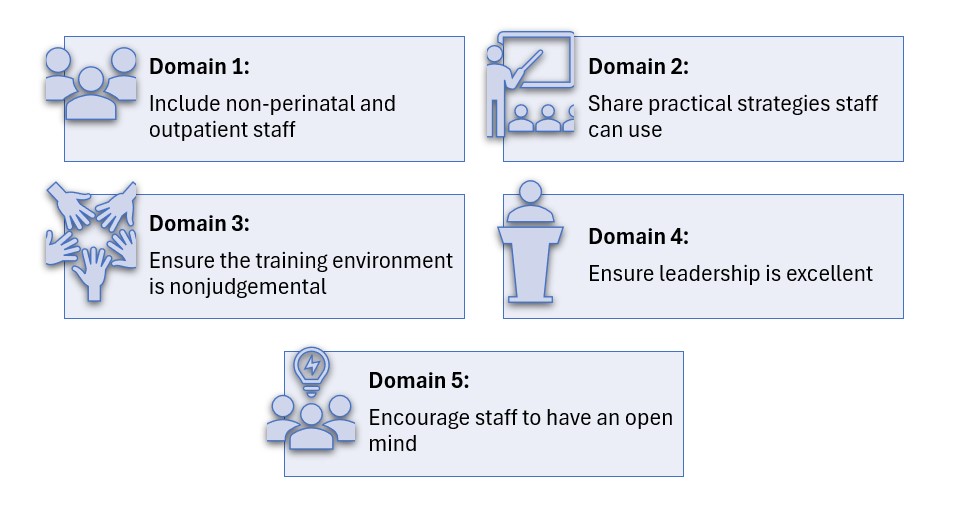

Implicit Bias Training (IBT) is a vital tool for reducing disparities in healthcare and improving patient outcomes in maternity care [26]. Effective IBT helps healthcare providers recognize and address their unconscious biases, leading to more equitable and compassionate care. The following domains outline key areas for enhancing IBT, offering practical strategies for its expansion, effectiveness, implementation, cultural integration within healthcare facilities, and fostering provider engagement.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How does mandatory implicit bias training, as required by laws like California's "Dignity in Pregnancy and Childbirth Act," impact the outcomes for Black pregnant persons and birthing people?

- Why is it crucial for healthcare providers to engage in education on implicit bias, and what effects might this have on their clinical practice and patient interactions?

- In what ways can public policy and federal initiatives, such as Title VI investigations, play a role in addressing discrimination and promoting diversity within the healthcare system?

- How can healthcare organizations implement comprehensive strategies—including diversity, equity, and inclusion programs and transparent reporting systems to manage and reduce implicit bias among clinicians and staff?

Implicit Bias Training Domains

Domain 1: Scope and Requirements of Implicit Bias Training (IBT)

Instructive Summary: To improve IBT, expand the scope to include non-perinatal and outpatient healthcare providers. Set clear guidelines on training frequency and duration, and establish accountability measures, such as penalties and standards linked to bias performance.

Domain 2: Effectiveness and Structure of IBT

Instructive Summary: For IBT to be effective, it must address systemic biases and provide practical strategies for clinicians. Use real patient stories and case studies to foster reflection and offer actionable insights for managing bias in clinical situations.

Domain 3: Implementing IBT in Healthcare Settings

Instructive Summary: Ensure successful IBT implementation by selecting credible trainers, including community members where possible, and creating safe, nonjudgmental training environments. Provide protected time, continuing education credits, and use data to assess the training's impact on clinical outcomes.

Domain 4: Healthcare Facility Culture and IBT

Instructive Summary: Leadership must demonstrate commitment to reducing bias, fostering trust, and encouraging open dialogue among staff. Implement accountability measures, such as tracking IBT participation and monitoring care quality, to ensure progress in addressing bias.

Domain 5: Provider Engagement and IBT

Instructive Summary: Providers must approach IBT with an open mind and work to recognize their own biases. Focus on engagement to prevent reactions, while understanding that even changes in behavior can improve outcomes.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How could expanding implicit bias training to include non-perinatal and outpatient providers, along with clear guidelines and accountability measures, impact the overall quality of healthcare delivery?

- In what ways might the commitment of healthcare leadership and the engagement of providers influence the success of implicit bias training in reducing disparities and improving patient outcomes?

- How do both conscious and unconscious biases among healthcare providers contribute to disparities in OB-GYN care affect treatment and outcomes for patients from lower socioeconomic backgrounds?

Conclusion