Course

Prostate Cancer Updates

Course Highlights

- In this Prostate Cancer Updates course, we will learn about the risk factors, symptoms, and diagnostic methods for prostate cancer.

- You’ll also learn the different treatment options available for prostate cancer, including medication management, new procedures, and interventions.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of common misconceptions about prostate cancer.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 1

Course By:

R.E. Hengsterman

RN, BS, MA, MSN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

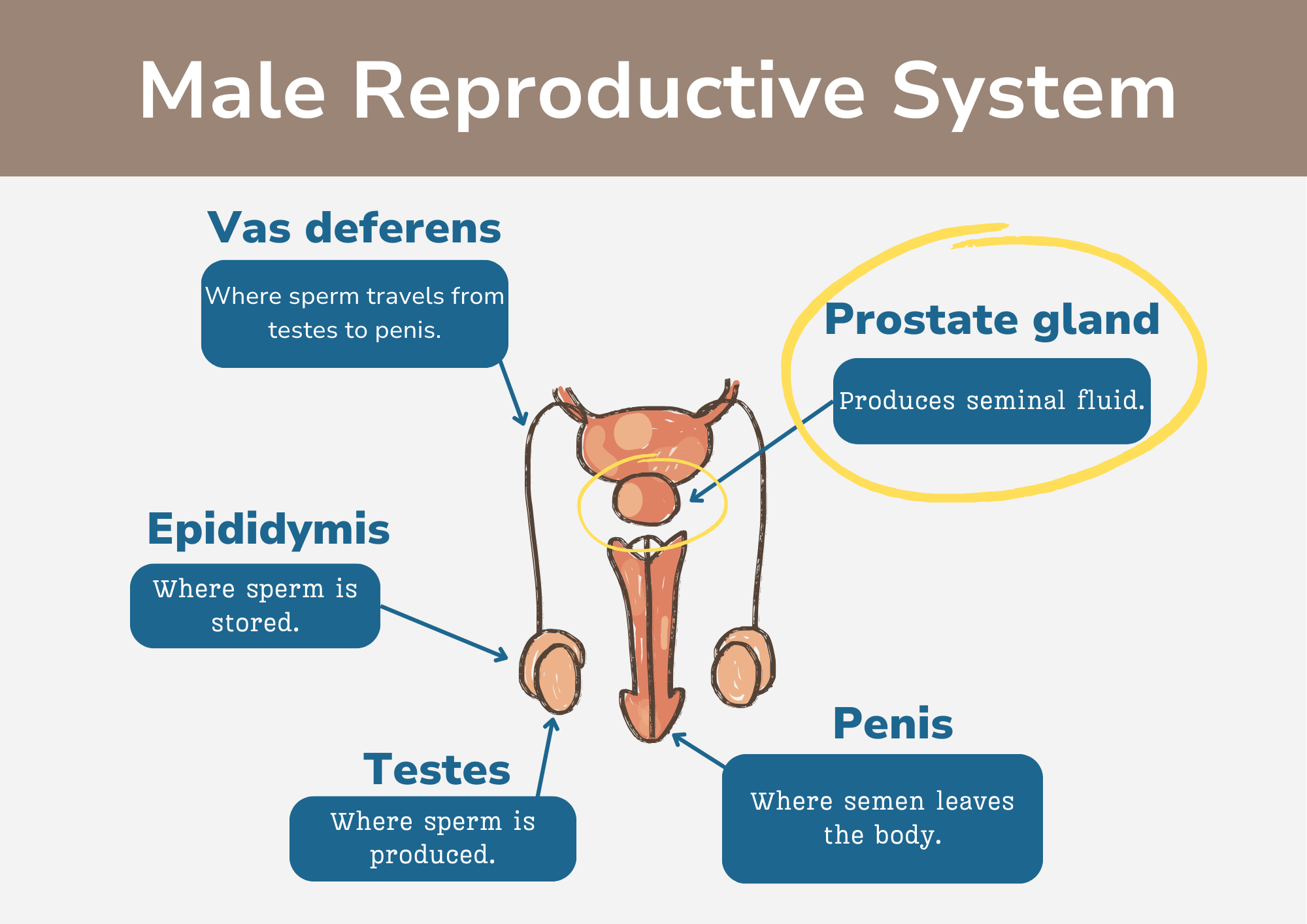

Nurses should be knowledgeable on the anatomy of the prostate, the devastating consequences of prostate cancer, and the implications for care from a nursing perspective. The prostate gland is a small, walnut-shaped gland located below the bladder and in front of the rectum. The prostate surrounds the urethra and is part of the male reproductive system, playing a key role in seminal fluids and reproduction, which nourishes and protects sperm cells. The prostate also helps to neutralize the acidic environment of the vagina, which can kill sperm cells (7). Androgens, such as testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT), are male sex hormones that are essential for the normal function of the prostate. The prostate also converts dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) into testosterone, and then later into DHT.

This design was created on Canva.com on December 13, 2023. It is copyrighted by Abbie Schmitt, RN, MSN and may not be reproduced without permission from Nursing CE Central.

Statistical Evidence/Epidemiology

Prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death among men in the United States, after lung cancer, and the most common cancer among men, after skin cancer (1). Research estimates that one in eight men will develop prostate cancer during their lifetime (1). In 2023, there will be over 288,000 new cases of prostate cancer diagnosed in the United States, and over 34,700 men will die from the disease (1). Worldwide, an estimated 1.5 million people received a diagnosed of prostate cancer in 2020, the 4th most diagnosed cancer in the world and the 5th leading cause of death worldwide (4).

The risk of prostate cancer increases with age, and most men receive a diagnosis over the age of 65 (2). family history of prostate cancer (first-degree relative), positive germline testing for BRCA1, BRCA2, Lynch Syndrome, changes in estrogen receptor α and β levels, androgen receptor signaling, as well as diets high in calories, fats, red meats, and dairy products can all contribute to prostate cancer (2, 27, 28).

The incidence of prostate cancer varies with the highest rates found in North America and Europe, while the lowest rates are found in Asia and Africa (5). The risk of prostate cancer is more common in non-Hispanic Black men and those of Caribbean descent (1). The reasons for these differences are due to a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

Since 1993, the prostate cancer death rate has declined by about 50% due to earlier detection and advances in treatment (1). The five-year survival rate for prostate cancer is over 99% when diagnosed at an early stage (3). However, the prognosis for metastatic prostate cancer is poor.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Why is it important to understand the risk factors for prostate cancer?

- What are the implications of the fact that prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death among men in the United States?

- With the five-year survival rate for early diagnosed prostate cancer being over 99%, how might providers work to ensure more early-stage diagnosis in patients, and what role could community education and awareness play in this?

- How can we improve early detection and treatment of prostate cancer, especially among men who are at considerable risk?

Etiology/Pathophysiology

Androgens are male sex hormones that play a key role in the development and growth of the prostate gland and are essential for its normal development and function. The most significant androgen is testosterone, which is converted to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in the prostate. DHT binds androgen receptors in prostate cells, which triggers a series of events that lead to both normal and cancerous prostate cells growth. Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a non-cancerous enlargement of the prostate gland that is common in older men (25).

Prostate cancer is often an adenocarcinoma, which is a cancer that develops from glandular cells. The most common location of prostate cancer is in the posterior lobe of the prostate (6). Prostate cancer is a multi-focal disease, meaning that it can develop in multiple areas of the prostate gland at the same time.

The prostate cancer grading system is based on a Gleason score. A Gleason score is based on how much cancer cells appear like healthy tissue when viewed under a microscope by a pathologist (8). Less aggressive tumors that appear more like healthy tissue receive a Gleason score of 6 or well differentiated. Tumors that are more aggressive appear less like healthy tissue receive a Gleason of 7 or moderately differentiated, medium-grade cancer. A score of 8, 9, or 10 is a high-grade cancer, poorly differentiated, or undifferentiated (8).

The staging of prostate cancer includes a PSA level and Gleason score.

Stage I: Cancer in this early stage and slow growing (8).

Stage II: A confined prostate tumor. PSA levels are medium or low (8). Stage II prostate cancer is small but may have an increasing risk of growing and spreading (8).

Stage IIA: The tumor is not palpable, and PSA levels are medium with well differentiated cancer cells (8).

Stage IIB: A confined prostate tumor that may be large enough to appreciate during a digital rectal exam (DRE) (8). The PSA level is medium and there is a moderate differentiation of the cancer cells.

Stage IIC: A confined prostate tumor that may be large enough to appreciate during a digital rectal exam (DRE) (8). The PSA level is medium and there is moderate or poor differentiation in the cancer cells.

Stage III: PSA levels are high, the tumor is growing, or the cancer is high grade (8).

Stage IIIA: The cancer has spread beyond the outer layer of the prostate into nearby tissues (8). It may also have spread to the seminal vesicles. The PSA level is high.

Stage IIIB: The tumor has grown outside of the prostate gland and may have invaded nearby structures, such as the bladder or rectum (8).

Stage IIIC: The cancer cells across the tumor are poorly differentiated (8).

Stage IV: The cancer has spread beyond the prostate (8).

Stage IVA: The cancer has spread to the regional lymph nodes (8).

Stage IVB: The cancer has spread to distant lymph nodes, other parts of the body, or to the bones (8). Recurrent prostate cancer is cancer that has returned after treatment.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Considering prostate cancer can be a multifocal disease, developing in multiple areas of the prostate gland, what challenges does this present in terms of diagnosis and treatment?

- Given that the Gleason score is determined by how much cancer cells resemble healthy tissue under microscopic examination, how might advancements in microscopic technology and techniques affect the precision and reliability of this grading system in the future?

- Considering the various stages of prostate cancer, including the recurrence of the disease post-treatment, what strategies might providers employ to monitor patients and prevent the progression to more severe disease?

- Given the noted disparities in the incidence and risks associated with prostate cancer in different demographic groups, what kind of multifaceted approaches can healthcare providers explore to address both the genetic and environmental factors contributing to these disparities?

Diagnostic and Screening tools

There are several tests used to diagnose prostate cancer. The most common tests are the digital rectal exam (DRE) and the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test measured in nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL) (9).

The role of PSA levels in prostate cancer is complex and not appropriate to solely use to diagnosis the disease. The PSA is a blood test that measures the level of PSA in the blood. Men greater than age 50 have a 20-30% risk of having prostate cancer if their PSA level is higher than 4.0 ng/mL. A PSA level between 2.5 and 4.0 ng/mL may require a biopsy to detect cancer in 27% of men (26).

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is a protein made by cells in the prostate gland (both normal cells and cancer cells). A high PSA level can be a sign of prostate cancer or other conditions, such as an enlarged prostate gland or prostatitis (10).

The DRE is a simple exam that involves the doctor inserting a gloved finger into the rectum to feel for any abnormalities in the prostate gland. A patient with an abnormal DRE or a high PSA level may require additional testing, such as a biopsy of the prostate gland. A biopsy involves removing a small sample of tissue from the prostate gland and examining it under a microscope for cancer cells. Providers can identify many prostate cancers with a medical history and physical exam.

(10)

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What role does PSA play in the diagnosis of prostate cancer?

- Given that a high PSA level can indicate not just prostate cancer but also other conditions like an enlarged prostate gland or prostatitis, how might medical professionals optimize the diagnostic process to differentiate between these different conditions?

- What approaches could providers take to encourage more frequent and routine screenings, and how might a focused educational campaign around the importance of these early diagnostic measures look?

- What are the potential benefits and risks of using new, more accurate tests for detecting prostate cancer, and how can we balance these factors to ensure that everyone has access to the best possible care?

Medication Management

Medications play a vital role in the management of prostate cancer. They can decrease tumors, slow tumor growth, and prevent metastases. Hormone therapy is a common treatment for prostate cancer and works by blocking the production of testosterone, the male hormone that fuels the growth of prostate cancer cells. LHRH (luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone) agonists prevent the testicles from receiving messages sent by the body to make testosterone (11).

GnRH antagonist (gonadotropin-releasing hormone) stops the testicles from producing testosterone (12). The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved degarelix (Firmagon) to treat advanced prostate cancer and an oral GnRH antagonist, relugolix (Orgovyx), for the treatment of advanced prostate cancer (12).

Androgen receptor (AR) inhibitors block testosterone from binding to androgen receptors, which are chemical structures in cancer cells that allow testosterone and other male hormones to enter the cells (14). Newer AR inhibitors include apalutamide (Erleada), enzalutamide (Xtandi), and darolutamide (Nubeqa) which can extend survival for some individuals with metastatic prostate cancer (13). Older AR inhibitors include bicalutamide (Casodex), flutamide (available as a generic drug), and nilutamide (Nilandron) taken orally.

The FDA approved Apalutamide for the treatment of non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer and for metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (15). Darolutamide can be a treatment option for non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (16). Darolutamide can be a combination therapy with docetaxel chemotherapy to treat metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. Enzalutamide is a nonsteroidal AR inhibitor approved to treat metastatic and non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer as well as metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (17).

Although the testicles produce most of the body’s testosterone, other cells in the body can still make lesser amounts of the hormone that may drive cancer growth. These include the adrenal glands and some prostate cancer cells. Androgen synthesis inhibitors that target an enzyme called CYP17 and stop cells from making testosterone (11). Androgen synthesis inhibitors include acetate (Zytiga) and Ketoconazole (Nizoral), an androgen synthesis inhibitor (11).

Chemotherapy is another common treatment for prostate cancer. In general, standard chemotherapy begins with docetaxel (Taxotere) combined with prednisone (11).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- How does the prostate gland respond to fluctuations in androgen levels, and what are the implications of this relationship for prostate health and disease?

- How can we develop more effective treatments for prostate diseases that consider the complex interplay between the prostate gland and androgens?

- What are the ethical implications of using androgen-based therapies to treat prostate diseases?

- Reflecting on the role of chemotherapy in treating prostate cancer, how might healthcare professionals balance the aggressive approach of chemotherapy with its potential side effects, and what strategies could be employed to maintain the quality of life for patients undergoing this treatment?

New Procedures and Interventions

There are several new procedures and interventions, either used or in development, to treat prostate cancer. Some of these new treatments include:

- High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU): HIFU uses sound waves to heat and destroy prostate cancer cells.

- Cryotherapy: Cryotherapy uses extreme cold to kill prostate cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy uses the body’s natural defenses to fight cancer by improving your immune system’s ability to attack cancer cells. Vaccination with sipuleucel-T (Provenge) may be an option. Sipuleucel-T is adapted for each patient (19).

- Precision medicine is an emerging approach to cancer treatment that uses genetics and other information to tailor treatments to the individual patient.

- Targeted therapy drugs are designed to attack specific molecules that are involved in the growth and survival of cancer cells with a PARP inhibitor (poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase) a protein that blocks an enzyme in cells and help repair DNA repair itself wen damaged (18).

- Targeted therapy for prostate cancer includes Olaparib (Lynparza), Rucaparib (Rubraca) Talazoparib (Talzenna) and Niraparib plus abiraterone (Akeega) (18).

- A clinical trial is underway to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a new targeted therapy drug called olaparib (Lynparza) in men with prostate cancer caused by specific genetic mutations (23).

- Checkpoint inhibitors block proteins on immune cells, making the immune system more effective at killing cancer cells (21).

- Two checkpoint inhibitors, pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and dostarlimab (Jemperli), have been approved for the treatment of tumors, including prostate cancers that have specific genetic features (21).

- Pembrolizumab has also been approved for any tumor that has metastasized and has a high number of genetic mutations (21).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Considering the emergence of these various innovative treatment options, how might healthcare providers integrate these approaches into existing treatment protocols to personalize care for patients with prostate cancer?

Common Misconceptions

There are several common misconceptions about prostate cancer. These misconceptions include:

Misconception: Prostate cancer is only a serious disease for older men. While it is true that the risk of prostate cancer increases with age, prostate cancer can also develop in younger men. In fact, about 1 in 8 men will receive a diagnosis of prostate cancer in their lifetime (1).

Misconception: Prostate cancer is always fatal. The five-year survival rate for prostate cancer is over 99% when diagnosed at an early stage (3).

Misconception: Masturbation or sex is a cause of prostate cancer. There is no evidence to support this claim. Prostate cancer is a combination of genetic and environmental factors, not by sexual activity.

Misconception: Prostate cancer is only a problem for men of African American descent. While it is true that African American men are more likely to develop prostate cancer than men of other races, prostate cancer can affect men of all races.

Misconception: Prostate cancer is only a problem for men with a family history of the disease. While a family history of prostate cancer can increase a man’s risk of developing the disease, most men with prostate cancer do not have a family history of the disease (4).

Misconception: There are no symptoms of prostate cancer. While early-stage prostate cancer often does not cause any symptoms, more advanced prostate cancer can cause symptoms such as difficulty urinating, frequent urination, and blood in the urine.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Considering that one misconception is that prostate cancer only affects older men, how can awareness campaigns communicate the importance of early detection and regular screenings across different age groups?

- Given that there is a misconception that prostate cancer is always fatal, how might healthcare leverage the survival rate statistics, in particular the over 99% survival rate for early-stage diagnoses, to foster hope and encourage early consultations and screenings?

Upcoming Research

The National Cancer Institute supported researchers who are developing new imaging techniques to improve the diagnosis of recurrent prostate cancer. A protein called prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is found in large amounts on prostate cells (20). By fusing a molecule that binds to PSMA to a compound used in PET imaging, scientists have been able to see tiny deposits of prostate cancer that are too small to be detected by regular imaging (20).

The Research on Prostate Cancer in Men with African Ancestry (RESPOND) study is the largest-ever coordinated research effort to study biological and non-biological factors associated with aggressive prostate cancer in African American men (22). The (RESPOND) study, launched by NCI and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities in partnership with the Prostate Cancer Foundation, is looking at the environmental and genetic factors related to the aggressiveness of prostate cancer in African American (22).

Researchers are developing a new blood test that can detect prostate cancer with high accuracy, even in men with early-stage disease (24). These tests are still in trials, but early results are promising. Their development is a significant step forward in the fight against prostate cancer. If the tests prove to be effective, they could revolutionize the diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Considering that the prostate cancer death rate has decreased due to early detection and advancements in treatment since 1993, what are potential areas of focus in research and healthcare policy to further this improved outcome?

Conclusion

Prostate cancer is a serious, but treatable disease. There are many different treatment options available, and the best treatment for a particular patient will depend on the stage and grade of the cancer, as well as the patient’s overall health. Early detection is key to successful prostate cancer treatment. Patients should talk to their doctor about the risks and benefits of prostate cancer and receive regular screenings.

References + Disclaimer

- American Cancer Society. (2023). Prostate cancer facts. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/prostate-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

- Cancer. Net. (2023). Prostate cancer – risk factors and prevention. (https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/prostate-cancer/risk-factors-and-prevention

- Survival rates for prostate cancer. (2023). American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html

- Prostate Cancer – statistics. (2023, May 4). Cancer.Net. https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/prostate-cancer/statistics

- Rawla, P. (2018). Epidemiology of prostate Cancer. World Journal of Oncology, 10(2), 63–89. https://doi.org/10.14740/wjon1191

- Oh, W. K. (2003). Biology of Prostate Cancer. Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK13217/

- Anamthathmakula, P., & Winuthayanon, W. (2020). Mechanism of semen liquefaction and its potential for a novel non-hormonal contraception†. Biology of Reproduction, 103(2), 411–426. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolre/ioaa075

- 8. Prostate Cancer – stages and grades. (2023, February 10). Net. https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/prostate-cancer/stages-and-grades

- What is screening for prostate cancer? (2022, March 14). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/prostate/basic_info/screening.htm

- Rigler, S. (2021). What are Some Other Causes of a High PSA? Prostate Cancer Foundation. https://www.pcf.org/blog/what-are-some-other-causes-of-a-high-psa/

- Prostate cancer – types of treatment. (2023, August 29). Cancer.Net. https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/prostate-cancer/types-treatment

- Hormone therapy for prostate Cancer fact sheet. (2021, February 22). National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/prostate-hormone-therapy-fact-sheet

- Darolutamide extends survival in metastatic prostate cancer. (2022, March 25). National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2022/darolutamide-survival-metastatic-prostate-cancer

- Davey, R. A. (2016, February 1). Androgen receptor Structure, Function, and biology: From bench to bedside. PubMed Central (PMC). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4810760/

- Research, C. F. D. E. A. (2018). FDA approves apalutamide for non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-apalutamide-non-metastatic-castration-resistant-prostate-cancer

- Yang, C., Cha, T., Chang, Y., Huang, S., Lin, J., Wang, S., Huang, C., & Pang, S. (2023). Darolutamide for non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: Efficacy, safety, and clinical perspectives of use. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 122(4), 299–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2022.12.008

- Rodriguez-Vida, A., Galazi, M., Rudman, S., Chowdhury, S., & Sternberg, C. N. (2015). Enzalutamide for the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Drug Design Development and Therapy, 3325. https://doi.org/10.2147/dddt.s69433

- FDA approves olaparib, rucaparib to treat prostate cancer. (2020, June 11). National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2020/fda-olaparib-rucaparib-prostate-cancer

- Thara, E., Dorff, T. B., Pinski, J., & Quinn, D. I. (2011). Vaccine therapy with sipuleucel-T (Provenge) for prostate cancer. Maturitas, 69(4), 296–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.04.012

- Kenny, L., & Aboagye, E. O. (2014). Clinical translation of molecular imaging agents used in PET studies of cancer. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 329–374). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-411638-2.00010-0

- Venkatachalam, S., McFarland, T. R., Agarwal, N., & Swami, U. (2021). Immune checkpoint inhibitors in prostate cancer. Cancers, 13(9), 2187. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13092187

- NIH and Prostate Cancer Foundation launch large study on aggressive. (2018, July 17). National Institutes of Health (NIH). https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-prostate-cancer-foundation-launch-large-study-aggressive-prostate-cancer-african-american-men

- LeVee, A., Lin, C. C., Posadas, E. M., Figlin, R. A., Bhowmick, N. A., Di Vizio, D., Ellis, L., Rosser, C. J., Freeman, M. R., Theodorescu, D., Freedland, S. J., & Gong, J. (2021). Clinical utility of Olaparib in the treatment of Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: A review of current evidence and patient selection. OncoTargets and Therapy, Volume 14, 4819–4832. https://doi.org/10.2147/ott.s315170

- Schlingman, J. (2023, March 16). US and UK Researchers Simultaneously Develop New Tests to Detect Prostate Cancer – Dark Daily. Dark Daily. https://www.darkdaily.com/2023/03/17/us-and-uk-researchers-simultaneously-develop-new-tests-to-detect-prostate-cancer/

- Banerjee, P. P. (2018). Androgen action in prostate function and disease. PubMed Central (PMC). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5902724/

- David, M. K. (2022, November 10). Prostate specific antigen. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557495/

- Rohrmann, S., Platz, E. A., Kavanaugh, C., Thuita, L., Hoffman, S. C., & Helzlsouer, K. J. (2007). Meat and dairy consumption and subsequent risk of prostate cancer in a US cohort study. Cancer Causes & Control, 18(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-006-0082-y

- Wang, G., Zhao, D., Spring, D. J., & DePinho, R. A. (2018). Genetics and biology of prostate cancer. Genes & Development, 32(17–18), 1105–1140. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.315739.118

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate