Course

Puerto Rico APRN Bundle Part 1

Course Highlights

- In this course, we will learn about the importance of bioethics in nursing practice.

- You’ll also learn the basic infection control practices and how to apply them.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of commonly prescribed opioids for pain management and understand their side effects and indications of use.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 20

Pharmacology contact hours included: 5

Course By:

Various Authors

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

Bioethics in Nursing

Introduction

Nursing practice is deeply rooted in ethical principles that guide decision-making and client care. Bioethics is a crucial aspect of healthcare that provides a framework for analyzing ethical dilemmas and promoting individualized client-centered care respectfully and compassionately. Nursing ethics involves applying bioethical principles in practice, such as maintaining client confidentiality and respecting autonomy. Nurses face ethical dilemmas regularly. One of the most common is providing care that conflicts with personal beliefs (6).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How do you think bioethics influences nursing practice

- What are some examples of ethical dilemmas nurses may face?

- Can you describe a situation where a nurse's personal beliefs conflicted with their professional obligations?

- How would you navigate such a scenario?

Definition and Purpose

Bioethics is the study of ethical and moral principles guiding healthcare decisions and practices (10). Its purpose is to ensure that healthcare providers make informed decisions that respect clients' values, beliefs, and rights (5).

Bioethics provides a framework for analyzing ethical issues in healthcare while considering the interests of the clients, their families, and the healthcare providers involved in their care (5). By understanding the definition and purpose of bioethics, nurses can develop a strong foundation for addressing ethical challenges in practice, such as informed consent, client confidentiality, and when it may infringe upon others’ health and proper resource allocation (5,6,10).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How does the definition of bioethics impact its application in nursing practice?

- What are some potential consequences of ignoring ethical principles?

- Can you think of a situation where a nurse's understanding of bioethics helped them navigate an ethical dilemma?

- What was the outcome?

Principles of Bioethics

The principles of bioethics include autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice (5,6,7,9). Autonomy respects clients' decision-making capacity, beneficence promotes a client's well-being, non-maleficence avoids any harm to the client, and justice ensures fairness and equity for all involved in the client’s care (5,6,9).

These principles serve as the guiding force in nursing practice; influencing the decisions related to client care, research, and policy development (1). Autonomy empowers clients to make informed choices about their care (5,6,9). This may include decisions that the client’s family and even healthcare providers may disagree with personally. Beneficence compels nurses to act in the best interests of their clients and advocate for the client’s desires (5,6,9). Non-maleficence reminds nurses to avoid causing harm; this includes not just physical but emotional and mental harm as well (5,6,9).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How do the principles of bioethics guide nursing practice?

- What are some examples of how these principles are applied in different healthcare settings?

- Can you describe a situation where a nurse had to balance the principles of autonomy and beneficence in their practice?

- How did they navigate this ethical dilemma?

Types of Ethics and Professions

Different professions have specific ethical guidelines, such as the American Nurses Association (ANA) Code of Ethics for nurses (1). Understanding the ethical framework of various professions is essential to the interdisciplinary healthcare approach.

Interdisciplinary collaboration requires an understanding of diverse ethical perspectives and principles, an approach that coincides with an equally diverse client population. Nurses should be aware of the ethical guidelines that govern their practice and be able to apply them in diverse healthcare settings. They must also be aware of their own beliefs and guidelines and how these may affect their decision-making, adversely affecting client care (5,6).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How do different professional ethical guidelines impact interdisciplinary collaboration?

- What are some potential consequences of ignoring these guidelines?

- Can you describe a situation where a nurse had to navigate an ethical dilemma with an interdisciplinary team?

Ethics in Nursing

Nursing ethics involves applying principles in practice that benefit the client, healthcare providers, and loved ones of the client. Examples include things such as maintaining client confidentiality and respecting autonomy, helping the client make the right decision for themselves, and advocating for those decisions to others (1,5). One of the most difficult decisions nurses face involves those that conflict with their personal belief system (6).

Nurses must be equipped with the knowledge and skills to navigate these ethical challenges and provide care that respects clients' values and beliefs while also nurturing their thoughts and feelings (6). By exploring bioethics in nursing, we can promote a culture of ethical practice that is compassionate and client-centered.

Henrietta Lacks Story

Henrietta Lacks was a Black tobacco farmer who had her cancer cells taken without her knowledge or consent which led to numerous scientific breakthroughs, including the development of the polio vaccine (7,8). Her story raises important questions about medical ethics, racism, and the intersection of science and human compassion.

In 1951, Henrietta Lacks was diagnosed with cervical cancer and began treatment at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. During her treatment, a sample collection of her cancer cells was taken by her doctor, Dr. George Gey without her knowledge and or consent (7,8). Dr. Gey discovered that Henrietta's cells were extraordinary in nature and could be of great value for cancer research and future developments as they could survive and thrive in a laboratory setting thus making them ideal for scientific research.

Henrietta's cells, known as HeLa cells, were soon being used in laboratories worldwide, leading to numerous scientific breakthroughs, including the polio vaccine development, in vitro fertilization, and gene mapping (7,8). However, Henrietta's family was never informed or financially compensated for the use of her cells, and her story remained largely unknown until the publication of Rebecca Skloot's book "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks" in 2010 (2).

Henrietta's story highlights the unethical practices that were common in the medical field at the time, particularly in relation to clients that lacked resources, particularly those belonging to minority groups (2). Her cells were taken without her consent, and she was never compensated or acknowledged for her contribution to science. This raised some very important questions about medical ethics, informed consent, and the exploitation of vulnerable populations.

Still, Henrietta's story is a powerful reminder of the intersection of science and the need for personal autonomy. Her cells have been used to advance scientific knowledge, but they also represent a person, a family, and a community. The use of her cells without her consent or compensation is a violation of her humanity and a reminder of the need for ethical considerations in scientific research.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How do nursing ethics impact patient care?

- What are some potential consequences of ignoring ethical principles in practice?

- Can you describe a situation where a nurse's understanding of ethics helped them provide high-quality care

- What were the benefits for the patient?

Tuskegee Syphilis Experiments

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study was a highly controversial and unethical medical experiment conducted on African American men in Macon County, Alabama between 1932 and 1972 (4,11). The study, led by the Department of U.S. Public Health Services, involved withholding treatment from hundreds of African American men infected with syphilis despite the availability of effective therapies, to study the natural progression of the disease (4,11).

The men, who were mostly illiterate and poor, were not informed that they had syphilis, their partners were not informed of the disease, nor were they given treatment for the disease (4,11). Instead, they were given placebos and misleading information about their condition. The study continued for 40 years, during which time many of the men died from syphilis-related complications, and many others suffered serious health problems which included the spreading of syphilis to unsuspecting sexual partners.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study is widely regarded as one of the most unethical medical experiments in history. The study was conducted without the men's knowledge or consent, and it violated basic human rights and principles of medical ethics. By way of public outcry and shock, the awareness of these experiments led to major changes in the way human subjects are protected in medical research and a desire for closer oversight by governing groups.

In 1974, a class-action lawsuit was filed on behalf of the men who were involved in the study, resulting in a multimillion-dollar settlement (11). The study also led to the establishment of the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, which developed guidelines for the ethical conduct of research involving human subjects (11).

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study has had a lasting impact on the field of medicine and beyond. It highlighted the importance of informed consent and the need for ethical oversight in the field of medical research. It has also led to the increased scrutiny of medical experiments and a greater emphasis on protecting human subjects, their privacy, and most importantly honest care and explanations of medical conditions and treatments.

Today, the Tuskegee Syphilis Study is remembered as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unethical medical research. It serves as a reminder of the importance of prioritizing the well-being and safety of people and the need for ongoing vigilance in ensuring that medical research is conducted ethically and responsibly, and ensuring there are the proper checks and balances in place to provide the oversight needed.

The study also highlighted the need for diversity in medical research and the importance of including diverse populations in clinical trials (11). It led to increased efforts to address health disparities and to ensure that medical research is conducted in a way that is fair and equitable to all.

In addition, the Tuskegee Syphilis Study led to changes in the way that medical research is regulated and overseen (11). It led to the establishment of institutional review boards (IRBs) and independent ethics committees (IECs) which are responsible for reviewing and approving research protocols and ensuring they meet the ethical standards set in place (11).

Transparency and accountability in medical research have also been placed at the forefront of research since these events took place. Highlighting the importance of disclosing potential conflicts of interest and ensuring research is conducted in a way that is transparent and open to scrutiny; there inevitably was major change and growth that came from this huge medical injustice.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study was a highly unethical and controversial medical experiment that had a profound impact on the field of medicine and beyond. It highlighted the importance of informed consent, ethical oversight, and diversity in medical research, and led to major changes in the way medical research is conducted and regulated. In these ways, it acted as a catalyst of growth and change in the way the U.S. views and treats research participants. It serves as a reminder of the need for ongoing vigilance in ensuring medical research is conducted ethically and responsibly.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Studies and Henrietta Lacks' cases highlight the importance of informed consent in research.

Other examples include: (5,9)

- Abortion and reproductive rights

- Euthanasia and end-of-life care

- Gene editing and genetic research

- Healthcare access and disparities

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How do bioethical issues like informed consent impact healthcare outcomes

- What are some potential consequences of ignoring these issues?

- Can you describe a situation where a bioethical issue like euthanasia sparked a debate?

- How did healthcare professionals navigate this ethical dilemma?

Research in Ethics

Research ethics involves applying bioethical principles in research (3). Obtaining informed consent and ensuring participant confidentiality are two ways in which the provider can best provide ethical care to those that entrust the healthcare system with their voluntary well-being.

Researchers must be aware of ethical principles that guide research and ensure their studies are conducted ethically and responsibly which puts the client first (3).

Ethical Decision-Making

Ethical decision-making involves critical thinking, moral principles, and professional standards. Nurses can use ethical frameworks, such as the MORAL model and Nursing Process model, to guide decision-making (5). Ethical decision-making is a crucial aspect of nursing practice as it enables nurses to navigate complex healthcare issues and promote clients' well-being.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How do ethical principles guide research?

- What are some potential consequences of ignoring these principles?

- Can you describe a situation where a researcher had to navigate an ethical dilemma in their study?

Conclusion

Bioethics plays a vital role in nursing practice, ensuring that clients receive respectful and compassionate care. Understanding bioethical principles and applications is essential for nurses to provide high-quality care. By applying ethical principles and frameworks, nurses can navigate complex healthcare issues and promote clients' well-being.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How does the ethical framework guide decision-making in nursing practice and what are some potential consequences of ignoring these frameworks?

- How do personal values and beliefs impact nursing practice what are the implications for patient care?

- How does the principle of autonomy impact informed consent in healthcare?

- What are some potential consequences of prioritizing beneficence over non-maleficence in healthcare, and how can nurses balance these principles?

- How does the concept of justice impact healthcare resource allocation and what are the implications for nurses and patients?

- How do nurses balance the need for patient confidentiality with the need for transparency?

- What are some potential consequences of ignoring the principle of non-maleficence in healthcare, and how can nurses prioritize patient safety?

- How does the principle of autonomy impact patient decision-making?

- How do nurses balance the need for patient education with the need for autonomy?

- Are there any potential consequences for prioritizing patient satisfaction over patient well-being?

- How does the concept of vulnerability impact healthcare ethics?

- How do nurses balance the need for patient advocacy with the need for patient autonomy?

- What are some potential consequences of ignoring the principle of justice in healthcare?

- How does the principle of beneficence impact healthcare resource allocation?

- How do nurses balance the need for patient education with the need for patient confidentiality?

- What are some potential consequences of prioritizing patient well-being over patient autonomy?

- Could the Henrietta Lacks case and the Tuskegee Syphilis cases have an affect the way minorities view medical treatment in the U.S?

Infection Control and Barrier Precautions

Introduction

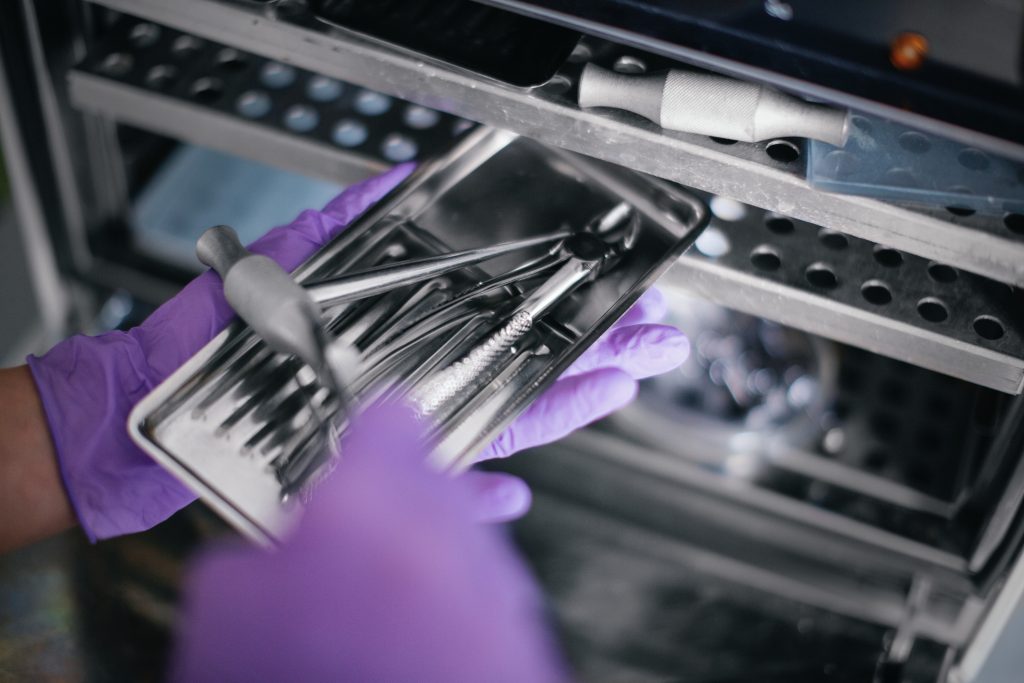

Healthcare professionals are responsible for adhering to scientifically accepted principles and practices of infection control in all healthcare settings. Healthcare professionals also oversee and monitor those medical and ancillary personnel for whom the professional is responsible, including nurses. The following sections explore the sources and definitions of standards of professional conduct as they apply to infection prevention and control (1,2).

Element I – Infection Control and Prevention Overview

As the largest healthcare workforce in the nation, nurses can positively affect infection rates at the bedside and within healthcare centers. Various agencies, workplaces, institutions, and legislation influence infection control and prevention recommendations, guidelines, and policies. As science and evidence-based research evolves, so does the role of infection control and prevention. It is important to remember that nurses set the stage for infection control and prevention efforts from the patient's point of view, as there was a time when nurses would care for patients without wearing gloves or washing hands. Hand washing, wearing gloves, and using masks are much more commonplace than ever in healthcare (1,2,3).

Implications of Professional Conduct Standards

As healthcare professionals who participate in and supervise patient care, nurses are responsible for knowing the guidelines set by their local, state, and federal legislation and nursing boards.

The responsibility also applies to delegated activities to other healthcare personnel. The nurse must ensure that the five delegation rights are considered when assigning a task to unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP) and that appropriate infection control policies and protocols are followed appropriately. Refer to facility policies and procedures to avoid potentially adverse outcomes (3,4).

Failure to follow the accepted infection prevention and control standards may have serious health consequences for patients and healthcare workers. Hospital-acquired infections (HAI) have increased overall in the past decade in all infections, including central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI), catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI), ventilator-associated infections, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (5,6). The chain of command should first be utilized when nurses observe incompetent care or unprofessional conduct regarding infection control standards.

Considering the type of misconduct, the infection control violation should be addressed according to facility policy. Charge nurses and managers would be wise to first address the issue with the nurse involved to gather information and address any education deficits. In cases where apparent misconduct is evident, management and workplace facilities should address infection control and prevention efforts. Severe misconduct may result in the loss or revocation of a nursing license. Also, in cases where the neglect to follow appropriate conduct has harmed a patient or coworker, there is potential for professional liability through a malpractice suit brought against the nurse (5,6,7,8,9).

Methods of Compliance

Nurses are responsible for knowing the licensure guidelines, renewal of continuing education, and targeted education in their state(s) of practice. Education on infection control best practices, compliance with local and state requirements, and following facility practices and policies will provide the best protection for self, patients, and staff in preventing and controlling infection during patient care.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are the consequences of a one-size-fits-all method for infection prevention?

- What are some infection control and prevention concerns you witness in your current workplace?

- How have infection control and prevention efforts changed throughout your nursing career?

- What is the policy in your workplace for reporting an infection control issue?

- How has infection control evolved in your workplace since the COVID-19 pandemic?

- How could natural disasters, such as hurricanes or tornadoes, influence the spread or development of infectious diseases?

Element II – Modes of Transmission

Modes and mechanisms of transmission of pathogenic organisms in the healthcare setting and strategies for prevention control.

Definitions:

Pathogen or infectious agent: A biological, physical, or chemical agent capable of causing disease. Biological agents may be bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa, helminths, or prions.

Portal of entry: How an infectious agent enters the susceptible host.

Portal of exit: The path by which an infectious agent leaves the reservoir.

Reservoir: A place in which an infectious agent can survive but may or may not multiply or cause disease. Healthcare workers may be a reservoir for several nosocomial organisms spread in healthcare settings, allowing an infection to be spread outside of healthcare settings into the general public.

Standard precautions: A group of infection prevention and control measures that combine the significant features of Universal Precautions and Body Substance Isolation and are based on the principle that all blood, body fluids, secretions, excretions except sweat, non-intact skin, and mucous membranes may contain transmissible infectious agents.

Susceptible host: A person or animal not possessing sufficient resistance to a particular infectious agent to prevent contracting infection or disease when exposed.

Transmission: Any mechanism by which a source or reservoir spreads a pathogen to a person.

Standard vehicle: Contaminated material, product, or substance that serves as a means of transmission of an infectious agent from a reservoir to one or more susceptible hosts through a suitable portal of entry (11,12,13).

Component of the Infectious Disease Process

The infectious disease process follows a particular sequence of events commonly described as the chain of infection. Nurses must have a solid understanding of this process to identify points in the chain where the spread of infection may be prevented or halted.

The sequence involves six factors: pathogen, reservoir, portal of exit, portal of entry, mode of transmission, and a susceptible host. The chain's cyclical and consistent nature provides many opportunities to use scientific, evidence-based measures to combat infection spread (11-19).

Pathogens within healthcare are widespread and plentiful, putting patients and healthcare workers at particular risk for contamination. The manifestation of symptoms and mode of transmission varies depending upon the characteristics of the specific infectious agent.

Healthcare workers are at a considerably higher risk for bloodborne pathogens, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV). Influenza, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), COVID-19, and Tuberculosis (TB) also pose a higher risk and can lead to chronic health damage. Due to the immunocompromised systems of several patients, pathogens cause a considerable risk. They can result in HAIs, such as CLABSIs, CAUTIs, surgical site infections (SSI), and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP).

Pathogens require a reservoir, typically a human or animal host; however, they may also be from the environment, such as standing water or a surface. The pathogen is spread from the reservoir via a mechanism such as body fluid, blood, and secretions. Common sites for contact within patient care include the respiratory, genitourinary, and gastrointestinal tracts, as well as skin/mucous membranes, transplacental, or blood. From here, the mechanism must come into contact with another portal of entry. Transmission may occur through respiratory, genitourinary, and gastrointestinal tracts, skin and/or mucous membranes, and parenteral pathways. Some sites may have compromised during patient care due to percutaneous injury, invasive procedures or devices, or surgical incisions.

To acquire a pathogen, a mode of transmission must be provided. Transmission can be from contact, transmission via a standard vehicle, or vector-borne (11-19).

Contact with a pathogen may be categorized as direct, indirect, droplet, or airborne. Contact transmission is through direct or indirect contact with a patient or objects in contact with the patient. Pathogens related to this include Clostridium difficile and multidrug-resistant organisms such as MRSA. Droplet transmission occurs when a pathogen can infect via droplets through the air by talking, sneezing, coughing, or breathing. The pathogen can travel three to six feet from the patient. Airborne transmission occurs when pathogens are 5 micrometers or smaller in size and can be suspended in the air for long periods.

These pathogens include TB, measles, chickenpox, COVID-19 disseminated herpes zoster, and anthrax. Transmission may also occur through a standard vehicle that affects multiple hosts and can come from food, intravenous fluid, medication, biofilms, or shared equipment (fomites), often leading to widespread outbreaks. Vector-borne pathogens are derived from living vectors such as mosquitoes, fleas, or ticks. The last factor in the chain of infection is a susceptible host with a mode of entry. This is why patients are at a much higher risk for developing secondary infections within the healthcare system, even if they had no infection before admission (11-19).

Factors Influencing the Outcome of Exposures

The human body provides several natural defenses against acquiring infection from a pathogen. The most prominent defense is the integumentary system, and the focus should be on maintaining skin integrity to prevent a mode of entry. This is especially true for patients who are immobile or unable to move without assistance, such as those who are post-operative, those with physical disabilities, or those who have extensive nerve damage—respiratory cilia function to move microbes and debris from the airway. Gastric acid is at a pH that prevents the growth of many pathogens. Bodily secretions provide defense through flushing out and preventing back-flow of potential infectious agent colonization. The normal flora within the gastrointestinal system also provides a layer of defense that must be protected from the action of antibiotics. Probiotics are commonly administered to patients on antibiotics to prevent a secondary infection due to disrupted normal flora. Host immunity is the secondary defense that utilizes the host’s immune system to target invasive pathogens. There are four types of host immunity(11-19):

- The inflammatory response is pathogen detection by cells in a compromised area that then elicit an immune response that increases blood flow. This inflammatory provides delivery of phagocytes or white blood cells to the infected site response. Phagocytes are designed to expunge bacteria.

- Cell-mediated immunity uses B-cells and T-cells, specialized phagocytes, which are cytotoxic cells that target pathogens.

- Humoral immunity is derived from serum antibodies produced by plasma cells.

- Immune memory is the immune system's ability to recognize previously encountered antigens of pathogens and effectively initiate a targeted response.

Pathogen or Infection Agent factors

For each type of infectious agent, specific factors determine the risk to the host. Infectivity refers to the number of exposed individuals that become infected. Pathogenicity is the number of infected individuals that develop clinical symptoms, and virulence is the mortality rate of those infected. The probability of an infectious agent causing symptoms depends upon the size of the inoculum (amount of exposure) and the route and duration of exposure. The environment is another factor that warrants attention in limiting the probability of exposure in the healthcare setting. Fomites are materials, surfaces, or objects capable of harboring or transmitting pathogens. Common fomites can be bedside tables, scrubs, gowns, bedding, faucets, and other items in contact with patients and healthcare providers. Equipment may factor into the spread of infection; incredibly portable medical equipment can contact numerous patients daily. This can include vital signs monitoring machines, IV pumps, wheelchairs, and computers on wheels, among countless other care items frequently used. Care must be taken to ensure cleaning in between each patient’s use. For patients in isolation precautions, dedicated equipment for that patient should remain in the room for the duration of their stay (11-17).

Methods to Prevent the Spread of Pathogenic Organisms

Standard Precautions

Standard precautions are the minimal caution and procedure applied to typical patient care. The basis of standard precautions is proper hand hygiene performed by healthcare providers, patients, and visitors. Standard precautions provide guidelines for respiratory hygiene and cough etiquette. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and emerging respiratory pathogen resurgence, such as TB and measles, many healthcare facilities are implementing masking for patients and staff, regardless of confirmed case or not, as part of their standard precautions. Hand hygiene must be performed after contact with respiratory secretions or potentially contaminated items. As mentioned, healthcare workers are at a higher risk for bloodborne infections due to the handling of sharps. Needle stick and sharps injuries are reported by healthcare workers in hospitals and outpatient care settings in upwards of 100,00 cases each year. Specific spinal procedures that access the epidural or subdural space provide a means of transmission for infections such as bacterial meningitis (7,8,15-22).

For Patients Infected with Organisms Other Than Bloodborne Pathogens

Special considerations must be given to patient populations infected with organisms other than bloodborne pathogens. A thorough health history should be obtained during the triage of a patient entering a facility. This would include exposure to infectious agents, travel to certain countries, and previous infections resistant to antibiotics (i.e., MRSA, VRE, TB, or carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae). Patients identified with a risk or history of any of these pathogens may be placed on the appropriate precautions in an isolation room. Infection prevention and the attending physician should be consulted immediately for further orders and treatment (20-22).

Control of Routes of Transmission

Controlling the routes of transmission is a key factor in preventing infection spread. Hand hygiene has been established as the primary prevention method (18).

Care must be taken to follow guidelines for proper hand washing, including:

- Use antibacterial soap and water when hands are visibly soiled or when a Clostridium difficile infection is known or suspected.

- Hands should be gathered. Scrubbing should last at least 20 seconds on all surfaces, between fingers, and under nails.

- Thoroughly rinse the soap from your hands with running water, pat dry with a paper towel, and use a paper towel to turn off the faucet.

- Hand sanitizer, at least 60% alcohol-based, between soap and water may be used.

- A dime-sized amount of hand sanitizer should be rubbed over the surface of hands and fingers and then allowed to air dry.

Barriers to proper hand hygiene include knowledge gaps and the availability of appropriate supplies. Training programs to educate healthcare providers on proper hand washing should be accompanied by ongoing assessment and feedback to ensure compliance.

Incorporating hand hygiene into each nurse's professional development plan is also recommended. Healthcare facilities should diligently ensure that hand washing stations are located in convenient areas and that hand cleaning products are frequently monitored and refilled. Signage and educational materials may be posted in high-traffic areas and at hand washing stations to encourage use by healthcare providers, patients, and visitors. Nurses and healthcare personnel must be aware of the potential of hand hygiene materials as being a potential source of contamination or cross-contamination. Hand hygiene dispensers are touched frequently with contaminated hands and must be often cleaned. It is recommended that the manufacturer's recommendations for cleaning be followed. Hand hygiene systems that allow products to be refilled pose a risk of contaminating the contents. If refilling is a requirement, this should be accomplished using an aseptic technique as much as possible. Facilities should avoid purchasing this product type and move to pre-filled dispensing units, if possible (1-4,18).

Use of Appropriate Barriers

Appropriate barriers are essential in keeping patients and healthcare providers safe from transmitting or contracting pathogens. The type of personal protective equipment (PPE) chosen depends on variables such as patient care, standard, and transmission-based precautions. The minimal amount of PPE recommended are as follows (18,20,21,22,23,24):

- Contact precautions include gloves and gowns. A mask and eye protection are required if bodily secretions may be contacted.

- Droplet precautions require a surgical mask.

- Airborne precautions require wearing gloves, a gown, and an approved N95 respirator mask that has been fit-tested for the individual wearing it. Unfavorable pressure rooms that can filter 6 to 12 air exchanges per hour are also recommended.

Be mindful that these are the minimal recommendations based solely on the identified transmission status of the patient. Selection of PPE should be made using critical thinking to identify potential risks depending on the type of patient care being performed, procedure, behavioral considerations, and other factors that may deviate from the standard. Confirming their infection control and prevention guidelines with your workplace is also essential. The following are current evidence-based recommendations for donning and doffing PPE(18,20,21,22,23,24):

How to Put On (Don) PPE Gear:

More than one donning method may be acceptable. Training and practicing using your healthcare facility’s procedure is critical, as facilities can vary in PPE supply and protocols. Below is one example of donning (18,20,21,22,23,24).

- Identify and gather the proper PPE to wear. Ensure the choice of gown size is correct (based on training).

- Perform hand hygiene using hand sanitizer.

- Put on an isolation gown and tie all of the ties on it. Other healthcare personnel may need assistance.

- Put on NIOSH-approved N95 filtering face-piece respirator or higher (use a facemask if a respirator is unavailable). If the respirator has a nosepiece, it should be fitted to the nose with both hands, not bent or tented. Do not pinch the nosepiece with one hand. The respirator/facemask should be extended under the chin. Both your mouth and nose should be protected. Please do not wear a respirator/facemask under your chin or store it in a scrubs pocket between patients.

- Respirator: Respirator straps should be placed on the crown of the head (top strap) and base of the neck (bottom strap). Perform a user seal check each time you put on the respirator.

- Face mask: Mask ties should be secured on the crown of the head (top tie) and base of the neck (bottom tie). If the mask has loops, hook them appropriately around your ears.

- Put on a face shield or goggles. When wearing an N95 respirator or half-face-piece elastomeric respirator, select the proper eye protection to ensure that the respirator does not interfere with the correct positioning of the eye protection and that the eye protection does not affect the fit or seal of the respirator. Face shields provide full face coverage. Goggles also offer excellent protection for the eyes, but fogging is common.

- Put on gloves. Gloves should cover the cuff (wrist) of the gown.

- Healthcare personnel may now enter the patient’s room.

How to Take Off (Doff) PPE Gear:

More than one doffing method may be acceptable. Training and practicing using your healthcare facility’s procedure is critical. Below is one example of doffing (18,20,21,22,23,24).

- Remove gloves one at a time. Ensure glove removal does not cause additional contamination of hands. Gloves can be removed using multiple techniques, such as the glove-in-glove or bird-beak.

- Remove the gown. Untie all ties (or unsnap all buttons). Some gown ties can be broken rather than untied. Do so gently, avoiding forceful movement. Reach up to the shoulders and carefully pull the gown away from the body. Rolling the gown down is an acceptable approach. Dispose of it in the designated trash receptacle.

- Healthcare personnel may now exit the patient’s room.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Remove face shields or goggles. Carefully remove them by grabbing the strap and pulling upwards and away from the head. Do not touch the front of your face shield or goggles.

- Remove and discard the respirator (or face mask if used instead of respirator). Do not touch the front of the respirator or face mask.

- Respirator: Remove the bottom strap by touching only it and carefully bringing it over the head. Grasp the top strap, carry it carefully over the head, and then pull the respirator away from the face without touching the front of the respirator.

- Face mask: Carefully untie (or unhook from the ears) and pull away from the face without touching the front.

- If your workplace practices reuse, perform hand hygiene after removing the respirator/face mask and before putting it on again.

Appropriate Isolation/Cohorting of Patients with Communicable Diseases

Co-hosting patients is a common practice within facilities, especially with limited rooms and an increasing number of patients with multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs). To combat these issues, placing patients with the same type of pathogen in one room when single rooms are unavailable is an option. The minimal standard for all patients is standard precautions (1,2,18,20,21,22,23,24).

Contact: If available, patients with a known or suspected pathogen transmitted via contact should be placed in a private room. Co-horting can be achieved if the co-horted patients share the same type of pathogen.

Droplet: Unless a single patient room is not available, patients in droplet precautions should only be co-horted if neither have an excessive cough or sputum production. The cohorts should be tested to ensure they are infected with the same type of pathogen. Immunocompromised patients are at an increased risk and should not be co-horted. Patients must be separated at least three feet apart, and a privacy curtain should remain between their respective areas. Care providers must don and doff new PPE while caring for each patient. Patients should be given masks to be worn when possible.

Airborne: An airborne infection isolation room (AIIR) with negative air pressure that exchanges air at least six to 12 changes per hour is required. The door must remain closed except for entry and exit. Co-horting of patients is not recommended except in the case of an outbreak or a large number of exposed patients. In these instances, evidence-based guidelines recommend the following:

- Consult infection control professionals before patient placement to determine the safety of alternative rooms that do not meet engineering requirements for AIIR.

- Place together (cohort) patients who are presumed to have the same infection (based on clinical presentation and diagnosis when known) in areas of the facility that are away from other patients, especially patients who are at an increased risk for infection (e.g., immunocompromised patients).

- Use temporary portable solutions (e.g., an exhaust fan) to create a hostile pressure environment in the converted area of the facility. Discharge air directly to the outside, away from people and air intakes, or direct all the air through high-efficiency particulate arresting (HEPA) filters before introducing it to other air spaces.

Host Support and Protection

Vaccinations to prevent disease are highly recommended by numerous health organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the World Healthcare Organization (WHO), and several public health departments (1,25-28). As healthcare providers, nurses are positioned to review the patient's history for gaps in appropriate vaccination coverage and educate the patient. Additionally, healthcare providers are ethically responsible for maintaining current vaccinations and can prevent transmitting known communicable diseases by receiving an influenza vaccination each year.

Further evidence suggests that additional boosters for tetanus and pertussis, COVID-19, and measles might benefit several nurses and patients. Pre- and/or post-prophylaxis may be recommended during specific exposures or for patients at an increased risk for infection. This is commonly used for emergent or planned procedures and surgeries that access areas at higher risk for becoming a portal of entry, such as the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary tracts. Antibiotics may be ordered when it is known that the sterile field has been broken during a procedure or there has been a concern of contamination of a wound or incision site (1,25-28).

In cases of exposure to an infectious pathogen, the decision to treat includes factors such as the type of exposure, source of the patient's symptoms, time frame since exposure, the health status of the individual exposed, and the risks and benefits of the treatment. Pre-prophylaxis may be considered in the prevention of HIV for high-risk individuals. Typically, after exposure, the host’s blood is drawn to determine pathogen risk regardless of if there is a known pathogen. Based on results, post-exposure prophylactics are given within a short time frame from the exposure. The individual who is exposed will have baseline testing for HIV, HBV, and HCV antibodies. Follow-up testing occurs six weeks, three months, and six months after initial exposure. Maintaining skin and immune system integrity is of the utmost importance to prevent the transmission of infectious pathogens (1,25-28).

Nursing interventions to promote skin and immune system integrity are (6):

- Perform a thorough skin assessment every shift and with changes in condition.

- Accurately document any wounds or incisions

- Use gentle cleansers on the skin and pat dry.

- Use moisturizers and barrier creams on dry or tender skin.

- Prevent pressure ulcer development by turning and repositioning the patient every 2 hours if the patient cannot move independently.

- Maintain aseptic technique during wound care, dressing changes, IV manipulation or blood draws, and catheter care.

- Use neutropenic guidelines when providing care to immunocompromised patients.

- Encourage adequate nutritional and hydration intake.

Environmental Control Measures

The cleaning, disinfection, and sterilization of patient care equipment should be performed per the manufacturer's and facility protocol's recommendations. Cleaning should be performed between each patient encounter. For equipment used in an isolation room, a terminal clean must be performed before being used in other patient care. Environmental cleaning personnel must be educated on the appropriate cleaning for all precautionary patient environments. The Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) for all chemicals are to be available to all healthcare personnel for reference as to the proper use and storage. These should be referred to ensure the correct cleaning product is effective in terminally cleaning isolation rooms based on pathogens (17,18,22,25).

Ventilation should be thoroughly managed and maintained by the environmental operations team. Unfavorable pressure rooms should be consistently monitored, and alarms should be investigated to ensure proper air exchange. Concerns from nursing regarding ventilation issues should be directed to the environmental team for follow-up. Regulated medical waste (RMW) within the healthcare system that must follow guidelines for disposal includes (17,18,22,25):

- Human pathological waste

- Human blood and blood products

- Needles and syringes (sharps)

- Microbiological materials (cultures and stocks)

- Other infection waste

Bodily fluid, such as urine, vomit, and feces, may be safely disposed of in any utility sink, drain, toilet, or hopper that drains into a septic tank or sanitary sewer system. Healthcare personnel must don appropriate PPE during disposal. Linen and laundry management in shared health facilities shall (17,18,22,25):

- Provide a sufficient quantity of clean linen to meet the requirements of patients.

- Separately bag or enclose used linens from infectious patients in readily identified containers distinguishable from other laundry.

- Transport and store clean linen in a manner to prevent contamination.

Environment controls include medical devices and systems to isolate or remove the bloodborne pathogens hazard from the workplace. These include sharps disposal containers, self-sheathing needles, and safer medical devices, such as sharps with engineered sharps injury protections and needleless systems. Per facility specifications, continuous training and education should be provided to healthcare personnel on the various methods and modes of environmental control measures that are put in place to prevent and contain pathogen spread (1,2,3).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How must an organization balance single-use versus reusable, portable medical equipment when considering infectious disease spread?

- What is your workplace's protocol for donning PPE?

- What is your workplace's protocol for doffing PPE?

- What common infections have been reported in your workplace?

- How often do you engage with leadership or management on HAI reduction measures?

- Have you ever cared for a patient with an HAI? How did they react or respond to knowing that they contracted an HAI? What education did you provide to this patient?

- Have you ever "brought home" a work infection? If so, what happened? Did your workplace provide any compensation or assistance?

- What is your workplace's protocol on needlestick and sharps exposure?

- How often do you and other nurses discuss PPE, infection control, and prevention in the workplace?

ELEMENT III – Infection Control in the Workplace

Engineering and work practice controls should be used to reduce the opportunity for patient and healthcare worker exposure to potentially infectious material in all healthcare settings (4-9).

Definitions (4-9)

Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs): Infections associated with healthcare delivery in any setting, such as hospitals, long-term care facilities, ambulatory settings, home care, etc.

Engineering Controls: Controls, such as sharps disposal containers, self-sheathing needles, and safer medical devices, such as sharps with engineered sharps injury protections and needleless systems, can isolate or remove the bloodborne pathogens hazard from the workplace.

Injection safety (or safe injection practices): A set of measures to perform injections optimally safely for patients, healthcare personnel, and others. A safe injection does not harm the recipient, expose the provider to any avoidable risks, and does not result in dangerous waste for the community. Injection safety includes practices intended to prevent transmission of bloodborne pathogens between one patient and another or between a healthcare worker and a patient and to prevent harm such as needlestick injuries. Single-use vials contain only one dose of medication and should only be used once for one patient, using a new sterile needle and a new sterile syringe.

Multidose medication vial: a bottle of liquid medication that contains more than one dose of drugs and is often used by patients with diabetes or for vaccinations.

Work Practice Controls: Controls that reduce the likelihood of exposure to bloodborne pathogens by altering how a task is performed, such as prohibiting the recapping of needles by a two-handed technique).

High-risk Practices and Procedures

Percutaneous exposures are a work hazard within the healthcare industry. Millions of healthcare workers are at risk, with nurses ranking number one. Studies have shown that needlestick injuries occur most frequently within a patient or operating room. Exposures can occur through not following safe practices. The following practices in handling contaminated needles and other sharp objects, including blades, can increase the risk of percutaneous exposure and should be avoided (1,2,3,4,7,17,18,19,22,24,26):

- Manipulating contaminated needles and other sharp objects by hand, such as removing scalpel blades from holders, removing needles from syringes

- Delaying or improperly disposing of sharps, such as leaving contaminated needles or sharp objects on counters/workspaces or disposing in non-puncture-resistant receptacles

- Recapping contaminated needles and other sharp objects using a two-handed technique

- Performing procedures where there is poor visualization, such as:

- Blind suturing

- Non-dominant hand opposing or next to a sharp

- Performing procedures where bone spicules or metal fragments are produced.

Mucous membrane/non-intact skin exposures occur with direct blood or body fluids contact with the eyes, nose, mouth, or other mucous membranes via:

- Contact with contaminated hands.

- Contact with open skin lesions/dermatitis.

- Splashes or sprays of blood or body fluids during irrigation, suctioning, or close contact

Parenteral exposure is subcutaneous (SC), intramuscular (IM), or IV contact with blood or other body fluid. Injection with infectious material may occur during:

- Administration of parenteral medication

- Sharing of blood monitoring devices, such as glucometers, hemoglobinometers, lancets, or lancet platforms/pens

- Infusion of contaminated blood products or fluids

- Human bites, abrasions, or cuts

Unsafe injection practices have resulted in more than 50 outbreaks of infectious disease transmission since 2001. As well, since that time, over 150,000 patients were potentially exposed to HIV, HBV, and HCV solely due to unsafe practices (1,2,3,4,7,17,18,19,22,24,26). These deviations from best practice have resulted in one or more of the following consequences:

- Transmission of bloodborne viruses

- Notification of thousands of patients of possible exposure to bloodborne pathogens and recommendation that they be tested for bloodborne pathogens

- Referral of providers to licensing boards for disciplinary action

- Malpractice suits filed by patients

Pathogens, including HCV, HBV, and HIV, can be present in sufficient quantities to produce infection in the absence of visible blood (26).

- Bacteria and other microbes can be present without clouding or other visible evidence of contamination.

- The absence of visible blood or signs of contamination in a used syringe, IV tubings, multi- or single-dose medication vial, or blood glucose monitoring device does NOT mean the item is free from potentially infectious agents, as many things cannot be seen, with the naked eye.

- All used injection supplies and materials are potentially contaminated and should be discarded.

Proper infection control techniques require that healthcare providers follow best practices to prevent injury and pathogen transfer. Aseptic techniques should always be used to prepare and administer an injection (14,15,17,26). The following are best practice guidelines:

- Medications should be drawn up in a designated “clean” medication area that is not adjacent to areas where potentially contaminated items are placed.

- Use a new sterile syringe and needle to draw up medications while preventing contact between the injection materials and the non-sterile environment.

- Ensure proper hand hygiene before handling medications.

- If a medication vial has been opened, the rubber septum should be disinfected with alcohol before piercing it.

- Never leave a needle or other device inserted into a medication vial septum or IV bag/bottle for multiple uses. This directly routes microorganisms to enter the vial and contaminate the fluid.

- Medication vials should be discarded upon expiration or when concerns arise regarding the medication's sterility.

Never administer medications from the same syringe to more than one patient, even if the needle is changed. Never use the same syringe or needle to administer IV medications to more than one patient, even if the drug is administered into the IV tubing, regardless of the distance from the IV insertion site (14,15,17,26).

- All infusion components are interconnected, from the infusion to the patient's catheter.

- All components are directly or indirectly exposed to the patient's blood and cannot be used for another patient. These components should also be discarded in the appropriate receptacle.

- Syringes and needles intersecting through any IV system port also become contaminated. They cannot be used for another patient or to re-enter a non-patient-specific multidose medication vial.

- Separation from the patient’s IV by distance, gravity, and/or positive infusion pressure does not ensure that small amounts of blood are not present in these items.

- Never enter a vial with a syringe or needle used for a patient if the same medication vial might be used for another patient.

Dedicate medication vials to a single patient, per your workplace's protocols (14,15,17,26), whenever possible.

- Medications packaged as single-use must never be used for more than one patient.

- Never combine leftover contents for later use

- Medications packaged as multiuse should be assigned to a single patient whenever possible.

- Never use bags or bottles of intravenous solution as a standard supply source for more than one patient.

- Never use peripheral capillary blood monitoring devices packaged for single-patient use on multiple patients.

- Restrict the use of peripheral capillary blood sampling devices to individual patients.

- Never reuse lancets. Use single-use lancets that permanently retract upon puncture whenever possible.

Evaluation/Surveillance of Exposure Incidents

A plan to evaluate and follow up on exposure incidents should be implemented at every facility. At a minimum, this plan should include the following elements (1,2,3,6,11,13,14,15):

- Identification of who is at risk for exposure

- Identification of what devices cause exposure

- Identification of areas/settings where exposures occur

- Circumstances by which exposures occur

- Post-exposure management

- Education for all healthcare employees who use sharps. This would include the fact that ALL sharp devices can cause injury and disease transmission if not used and disposed of properly. Specific focus should be on the devices that are more likely to cause injury, such as:

- Devices with higher disease transmission risk (hollow bore) and

- Devices with higher injury rates (“butterfly”-type IV catheters, devices with recoil action)

- Blood glucose monitoring devices (lancet platforms/pens).

Engineer Controls

Engineer controls are implemented to provide healthcare workers with the safest equipment to complete their jobs. Safer devices should be identified and integrated into safety protocols whenever possible. When selecting engineer controls to be aimed at preventing sharps injuries, the following should be considered (1,2,3,6,11,13,14,15):

- Evaluate and choose safer devices

- Passive vs. active safety features

- Mechanisms that provide continuous protection immediately

- Integrated safety equipment vs. accessory devices:

- Properly educate and train all staff on safer devices.

- Consider eliminating traditional or non-safety alternatives whenever possible.

- Explore engineering controls available for specific areas/settings.

- Use puncture-resistant containers for the disposal and transport of needles and other sharp objects:

- Refer to published guidelines for sharps disposal container selection, evaluation, and use (e.g., placement).

- Use splatter shields on medical equipment associated with risk-prone procedures (e.g., locking centrifuge lids).

Work Practice Controls (1,2,3,6,11,13,14,15,17,18)

- General practices:

- Hand hygiene includes the appropriate circumstances in which alcohol-based hand sanitizers, soap, and water hand washing should be used.

- Proper procedures for cleaning blood and body fluid spills

- Initial removal of bulk material followed by disinfection with an appropriate disinfectant.

- Proper handling/disposal of blood and body fluids, including contaminated patient care items.

- Proper selection, donning, doffing, and disposal of PPE as trained

- Adequate protection for work surfaces in direct proximity to patient procedure treatment area with appropriate barriers to prevent instruments from becoming contaminated with bloodborne pathogens

- Preventing percutaneous exposures:

- Avoid unnecessary use of needles and other sharp objects

- Use care in the handling and disposing of needles and other sharp objects:

- Avoid recapping unless medically necessary

- When recapping, use only a one-hand technique or safety device

- Pass sharp instruments using designated “safe zones."

- Disassemble sharp equipment by use of forceps or other devices

- Discard used sharps into a puncture-resistant sharps container immediately after use

Modify Procedures to Avoid Injury (1,2,3,6,11,13,14,15,17,18):

- Use forceps, suture holders, or other instruments for suturing

- Avoid holding tissue with fingers when suturing or cutting

- Avoid leaving exposed sharps of any kind on patient procedure/treatment work surfaces

- Appropriately use safety devices whenever available:

- Always activate safety features

- Never circumvent safety features

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What best practices should always be employed when delivering injections and intravenous medications?

- Have you or a coworker experienced a needlestick injury at work? How was that situation managed?

- What sort of infection surveillance does your workplace use, such as documentation notes, managerial updates, and so on?

- How has what you learned in nursing school changed the infection prevention and control measures you practice in your nursing career?

- Are nurses in your workplace involved in infection surveillance? If so, what is the nurse's role in infection surveillance?

- What role does leadership take in infection surveillance and HAI reduction?

- What is your workplace's policy on multiuse vials?

- How often do you wash your hands during a typical nursing shift? Do you tend to wash your hands more or use hand sanitizer more?

ELEMENT IV – Defining PPE

Selection and use of barriers and/or personal protective equipment for preventing patient and healthcare worker contact with potentially infectious material (19-26).

Definitions

Personal protective equipment (PPE) is specialized clothing or equipment an employee wears to protect against a hazard. PPE is typically for one-time use but can be reused depending on the supply, protocol, and infection prevention measures in place.

Barriers: Equipment such as gloves, gowns, aprons, masks, or protective eyewear can reduce the risk of exposure of the healthcare worker's skin or mucous membranes to potentially infective materials (19-26).

Types of PPE/Barriers and Criteria for Selection

Per OSHA guidelines, employers must provide employees with appropriate PPE that protects them from potential infectious pathogen exposure. PPE includes gloves, coveralls, masks, face shields, and eye protection. All PPE is intended to provide a barrier between the healthcare worker and potential contamination, whether from a patient, object, or surface (19-26).

Gloves are intended to provide coverage and protection for hands. There are several types of gloves, and the kind of patient care or activity should guide choice (19-26).

- Sterile – to be utilized when performing sterile procedures and aseptic technique

- Non-sterile – medical grade, non-sterile gloves may be used for general patient care and clean procedures, such as nasogastric tube insertion

- Utility – not medical grade and should not be used in patient care

The choice of glove material is often dictated by cost and facility preference. When given a choice, considerations should be made regarding the material being handled (19-26).

- Natural rubber latex – rarely used in facilities due to allergen risk

- Vinyl – made from PVC, lower in cost, protects in non-hazardous and low-infection environments

- Nitrile – more durable, able to withstand chemical and bio-medical exposure

An appropriately sized glove fits securely to the fingertips and palm without tightness or extra room. A glove should be replaced immediately if it develops a tear or is heavily soiled.

A cover garb is a protective layer worn over scrubs or clothes to protect garments and skin. Examples include laboratory coats, gowns, and aprons. As with gloves, consideration should be given to size, sterility, the type of patient care involved, and the material characteristics of the gown.

- Fluid impervious – does not allow passage of fluids

- Fluid resistant – resists penetration of fluids, but fluid may seep with pressure

- Permeable – does not offer protection against fluids

Masks protect the wearer’s mouth and nose, with respirators providing an extra layer of protection to the respiratory tract against airborne infection pathogens. Goggles are designed to protect the eyes from splashes and droplet exposure, while face shields offer additional protection to the entire face. It is important to note that face shields are not designed to replace masks (19-26,28). The choice of PPE is based on the factors reasonably anticipated to occur during the patient care encounter. Potential contact with blood or other infectious material can occur via splashes, respiratory droplets, and/or airborne pathogens.

The type of PPE chosen will be based on standard or transmission-based precaution recommendations. Follow your facility policy and procedures for guidance on the appropriate choice. The nurse must also anticipate whether fluid will be encountered, such as emptying a drain or foley collection device. In situations where a large amount of fluid is likely to be experienced, it would be wise to choose a higher level of protection, such as an impermeable gown, if available, and to wear eye protection to ward off splashes (19-26). Choosing Barriers/PPE Based on Intended Need

Barriers and PPE are designed to keep patients and healthcare providers safe. In certain circumstances, specific PPE is selected based on patient care or circumstances (19-26).

Patient Safety

During invasive procedures, such as inserting a central line or during surgery, staff directly involved in performing the procedure or surgery must maintain sterility. Appropriate sterile PPE will be selected based on the type of procedure, and the patient will be draped in a sterile fashion according to recommended guidelines. Patients in droplet precautions pose a significant risk to healthcare workers and visitors. The patient and anyone inside the patient's room should wear a mask for the most effective prevention of transmission (19-26).

Employee Safety

Employees must evaluate the types of exposure that are likely to occur during patient care. Selection of PPE and appropriate barriers should consider the following (19-26,28):

Barriers to contamination prevention (16,19-26,28):

- Standard precautions are to be used with any potential exposure to blood, mucous membranes, compromised skin, contaminated equipment or surfaces, and body fluids. Barriers may include gloves, gowns, and eye and face protection.

- Employees must be judicious in identifying any precautions placed on a patient (e.g., contact, droplet, airborne) and following recommended PPE guidelines to protect themselves and other patients.

- PPE should be donned prior to entering a patient room and doffed upon exit. All gloves must be changed between uses, and hands must be washed or sanitized upon removal of gloves.

- Additionally, social distancing of 6 feet should occur within the work environment whenever possible. When not possible, adherence to mask guidelines is sufficient.

Masks for preventing exposure to communicable diseases (16,19-26,28):

With the onset of COVID-19 across the globe, masks are an essential tool in preventing the transmission of respiratory pathogens. At a minimum, a medical mask must be donned during all patient care, and surgical masks must be utilized during procedures or surgery.

N95 masks are reserved for patient care with known or suspected COVID-19 or other airborne pathogens if airborne precautions are ordered or during procedures that may aerosolize, such as during intubations or specific endoscopy procedures.

Standard N95 respirators are recommended for all other care involving confirmed or suspected Covid-19 patients.

Guidance on Proper Utilization of PPE/Barriers (16,19-26,27,28)

Proper fit is required for PPE to be adequate, as everyone has different body sizes and facial structures that can influence PPE effectiveness. The gowns and gloves chosen should fit well, allow movement, and not be too baggy or too tight. For particulate respirators, all workers required to wear tight-fitting respirators (e.g., N95 respirators, elastomeric) must have a medical evaluation to determine the worker's ability to wear a respirator. If medically cleared, a respirator fit test must be performed using the exact model available in the workplace. Before donning PPE, it should be inspected for anomalies, tears, or vulnerable spots. A compromised PPE should be disposed of, and a new garment should be selected. Nurses must consider the selection of PPE to ensure that it is the correct type for the job and anticipate any circumstances where splashes or fabric saturation is likely to occur. The PPE provided by the employer may be single-use or reusable. Always verify with the manufacturer’s guidelines and facility policy on correctly using and processing worn garments. The facility must ensure that reusable gowns are laundered according to local, state, and federal guidelines.

Healthcare facilities have a legal duty to protect their workers. Employers and healthcare workers must understand the cost versus benefit ratio balance in PPE selection and use. While it is important to be good stewards of resources, always erring on the side of caution and choosing PPE based on anticipated exposure risk is the most effective way to protect healthcare workers and patients.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How would you handle working at an organization that does not provide sufficient PPE to protect frontline staff?

- What is an example of an acceptable refusal by a healthcare provider to don PPE?

- What do you think causes healthcare providers to forgo established safety measures?

- What other industries are healthcare analogous to when considering the safety of people?

- What are your workplace's policies on PPE?

- Have you ever had to educate a patient on PPE? How was that conversation? What talking points would you address when talking about PPE with a geriatric patient compared to a pediatric patient?

- How involved are nurses in your workplace in PPE use, cost, and distribution?

- If a patient developed an allergic reaction to PPE, how would you handle that situation?

- How can caregivers play a role in a patient's health history?

ELEMENT V – Maintaining a Safe Environment (1,2,3,29)

Create and maintain a safe environment for patient care in all healthcare settings by applying infection control principles and practices for cleaning, disinfection, and sterilization.

Definitions

Contamination: The presence of microorganisms on an item or surface.

Cleaning: The process of removing all foreign material (dirt, body fluids, lubricants) from objects by using water and detergents or soaps and washing or scrubbing the object

Critical device: An item that enters sterile tissue or the vascular system (e.g., IV catheters, needles). These must be sterile before contact with tissue.

Decontamination: The use of physical or chemical means to remove, inactivate, or destroy bloodborne pathogens on a surface or item to the point where they can no longer transmit infectious particles.

Disinfection: The use of a chemical procedure that eliminates virtually all recognized pathogenic microorganisms but not necessarily all microbial forms (bacterial endospores) on inanimate objects.

High-level disinfection: This type of disinfection kills all organisms except high levels of bacterial spores and is affected by a chemical germicide cleared for marketing as a sterilant by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Intermediate level disinfection: Disinfection that kills mycobacteria, most viruses, and bacteria with a chemical germicide registered as a “tuberculocide” by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Low-level disinfection: Disinfection that kills some viruses and bacteria with a chemical germicide registered as a hospital disinfectant by the EPA.

Noncritical device: An item that contacts intact skin but not mucous membranes (e.g., blood pressure cuffs, oximeters). It requires low-level disinfection.

Semi-critical device: An item that comes in contact with mucous membranes or non-intact skin and minimally requires high-level disinfection (e.g., oral thermometers, vaginal specula).

Sterilization: Using a physical or chemical procedure to destroy all microbial life, including highly resistant bacterial endospores.

Universal Principles (1,2,3,29)

Instruments, medical devices, and equipment should be managed and reprocessed according to the recommended and appropriate methods regardless of a patient's diagnosis, except for suspected prion disease cases. Because of the infective nature and steam-resistant properties of prion diseases, special procedures are required for handling brain, spinal, or nerve tissue from patients with known or suspected prion disease, such as Bovine spongiform encephalopathy [BSE].

Consultation with infection control experts before performing procedures on such patients is warranted. Industry guidelines, equipment, and chemical manufacturer recommendations should be used to develop and update reprocessing policies and procedures. Written instructions must be made available for each instrument, medical device, and equipment reprocessed (1,2,3,29).

Potential for Contamination (1,2,3,29)

The type of instrument, medical device, equipment, or environmental surface cause variables more likely to be a source of contamination. The presence of hinges, crevices, or multiple interconnecting pieces may cause external contamination. If able, these devices should be disassembled. Endoscopes provide a particular challenge for internal and external contamination because of their lumens and the crevices and joints present. The disinfectant must reach all surfaces and ensure no air pockets or bubbles impede penetration. As well, these devices may be made of material that is not heat resistant, which prevents the ability to sterilize.

In these instances, chemicals must be utilized to provide disinfection. Once rendered sterile, there are multiple opportunities for potential contamination because of the frequency of hand contact with the device or surface. Packaging may be overhandled and breached. If the item may come into contact with potential contaminants via poor storage, improper opening, or environmental factors, follow facility protocol for sterilization and disinfection. The efficacy of sterilization and disinfection depends on the number and type of microorganisms present. Various pathogens carry an innate resistance, making successful decontamination more challenging. Bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa, and prions cause most infections. Because of the nature of their outer membranes, spores, and gram-negative bacteria have a natural barrier that prevents the absorption of disinfectants.

Bacterial spores are incredibly resistant to chemical germicides. The number of microorganisms present on a medical instrument, device, or surface affects the time that must be factored into disinfection and sterilization efficacy (1,2,3,29). Generally, used medical devices are contaminated with a relatively low bioburden of organisms. Inconsistencies or incorrect methods of reprocessing can easily lead to the potential for cross-contamination.

Steps of Reprocessing (1,2,3,29)

Reprocessing medical instruments and equipment is completed sequentially depending on the instrument and chosen process.

Pre-cleaning removes soil, debris, and lubricants from internal and external surfaces through mopping, wiping, or soaking. After use, it must be done as soon as possible to lower the number of microorganisms on the object.

Cleaning may be accomplished manually or mechanically. Manual cleaning relies upon friction and fluidics (fluids under pressure) to remove debris and soil from the instrument's inner and outer surfaces. Several machines are used in mechanical cleaning, including ultrasonic cleaners, washer-disinfectors, washer-sterilizers, and washer-decontaminators.

Disinfection involves using disinfectants, either alone or in combination, to reduce the microbial count to near insignificant. Common disinfectants used in the healthcare setting include chlorine and chlorine compounds, hydrogen peroxide, alcohols, iodophors, and quaternary ammonium compounds. The EPA and FDA formulate and approve these products for specific uses.

Most medical and surgical devices in healthcare facilities are sterilized. This requires sufficient exposure time to heat, chemicals, or gases to ensure that all microorganisms are destroyed.

Choice/Level of reprocessing sequence (1,2,3,29)

The choice or Level of reprocessing is based on the intended use:

- Critical instruments and medical devices require sterilization.

- Semi-critical instruments and medical devices minimally require high-level disinfection.

- Noncritical instruments and medical devices minimally require cleaning and low-level disinfection.

Manufacturer and workplace recommendations must always be consulted to ensure that appropriate methods, actions, and solutions are used. There is a wide variety of compatibility among equipment components, materials, and chemicals. Rigorous training is required to appropriately understand the various equipment heat and pressure tolerance and the time and temperature requirements for reprocessing. Failure to follow the manufacturer or workplace recommendations may lead to equipment damage, elevated instrument microbial counts after reprocessing, increased infection risk, and possibly patient death (1,2,3,29).

Effectiveness of reprocessing instruments, medical devices, and equipment (1,2,3,29)

Pre-cleaning and cleaning before disinfection is one of the most effective ways to reduce the microbial count. This is only effective when completed before disinfection. Disinfection relies upon the action of products to eliminate microbial count. Depending on the medical instrument or device design, the product may only be required to cover the surface.

However, immersion products and dwell times are necessary because of the lumens of scopes, crevices, or hinges on specific instruments. The presence of organic matter, such as blood, serum, exudate, lubricant, or fecal material, can drastically reduce the efficacy of a disinfectant. This may occur because the presence of organic material acts as a barrier. It may also arise from a chemical reaction between the organic material and the disinfectant being utilized.

Biofilms pose a particular challenge and offer protection from the action of disinfectants. Biofilms are composed of microbes that build adhesive layers onto objects' inner and outer surfaces, including instruments and medical devices, rendering certain disinfectants ineffective. Chlorine and Monochloramines remain effective against inactivating biofilm bacteria.

After disinfection, staff and management must adopt a system of record keeping and tracking of instrument usage and reprocessing. Reprocessing equipment must be maintained and regularly cleaned on a schedule, according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. There are several methods of sterilization, such as steam sterilization (autoclaves), flash sterilization, and, more recently, low-temperature sterilization techniques created for medical devices that are heat sensitive.

Selection depends upon the type of instrument, material, ability to withstand heat or humidity, and targeted microbes. There are several methods of ensuring that sterilized instruments are processed and tracked appropriately. Indicators or monitors are test systems that verify that the sterilization methods were sufficient to eradicate the regulated number of microbes during the process. These safeguards include (1,2,3,29):

- Biologic monitors

- Process monitors (tape, indicator strips, etc.)