The Basics of Wound Healing

Contact Hours: 3

Author(s):

Melody Heffline MSN, APRN, ACNS-BC, ACNP-BC, ACHPN

Course Highlights

- In this course, we will learn about the various types of wounds and why nurses need to be prepared to treat them effectively.

- You’ll also learn the basics of wound healing phases, assessments, and management.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of how to care for wounds and evaluate their healing status properly.

Introduction

Wounds! Just the word can strike terror into some of our hearts. However, once you get to know them, you can relax and use what you know to give them the best care possible. So come along with me, and let’s break down the basics of wound healing together! Hopefully, you will learn to love them as I have because they are here to stay and become more common every day. On top of this, they are costly to the healthcare system. Wounds can cross over many areas of nursing, so no matter where you practice, chances are you will encounter a wound and need to know how to care for it. Let’s journey into the types of wounds we may see, what hinders them from healing, how to attack those hindrances, and how to manage wounds to get them to the finish line!

Case Study

Let’s meet our patient, Ms. E, whom we will look at throughout this lesson.

She is a 56 y/o female with peripheral arterial disease who developed an arterial thrombus in her right lower extremity. Unfortunately, though she responded to thrombolytic therapy and flow was restored to her leg, it did not happen before she developed compartment syndrome in her leg, requiring fasciotomy. Her medial incision was able to be closed in a delayed fashion, about 48 hours after the surgery. However, she still had significant edema in the leg, and the lateral incision had to be left open to granulate by secondary intention.

Her past medical history includes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus with hyperglycemia, tobacco dependence (two packs per day at the time of her event), morbid obesity with a body mas index (BMI) of 50.7, coronary artery disease (CAD) with previous myocardial infarction (MI), and coronary stent placement. Blood sugars at the time of the event were running in the 200-300 range with an A1C of 10.3. She has frequent exacerbations of her COPD, requiring steroids and antibiotics.

She has significant edema in the lower extremities due to a lack of elevation. She is allergic to ciprofloxacin, cephalexin, levofloxacin, and latex. She was started on warfarin following thrombolysis of the thrombus, but due to significant issues with attempting to stabilize her INR (international normalized ratio; test for bleeding times), she was switched to apixaban twice daily and clopidogrel daily. To say the least, getting this large fasciotomy wound to heal will be challenging.

Ask yourself...

- What additional assessments do you want to complete with this patient?

- What laboratory tests would be beneficial for this patient?

- What comorbidities can cause the patient to have decreased wound healing?

- Which of the patient’s medications places the patient at an increased risk of complications?

- What education would you want to provide to that patient regarding their wound healing?

Wound Types

To develop a thorough understanding of wound healing, let’s start with a simple definition of a wound. A wound happens when the skin is traumatically disrupted. This can occur in a controlled fashion, such as with surgery, or in a more traumatic fashion, such as bites from pets or other animals, gunshots, or lacerations, creating a jagged-edged wound.

Surgical Wounds

Surgical wounds may be further classified into wounds that are:

- Clean (uninfected)

- Clean-contaminated (in the respiratory, gastrointestinal/GI, genitourinary/GU tract)

- Contaminated (the result of trauma or loss of sterile technique)

- Dirty (infected)

When a wound is clean or clean-contaminated, it can be closed at the end of a surgical procedure. If a wound is contaminated or dirty, it is usually left open at the end of the surgery because its bacterial burden is too high. Closing this wound is generally futile because it can lead to infection. This wound can be better managed if left open. Wounds closed surgically are defined as primary closure. Wounds are left open to heal by secondary intention, allowing granulation tissue to form and eventually allowing the wound to close independently. Some scars can be left open to allow for infection treatment and then closed in a delayed fashion (1, 2). This is the case with Ms. E’s wound.

Wounds may be larger, such as those from auto accidents, where we see crush injuries, traumatic amputation, or even burns and thermal injuries. Initially, wounds are classified as acute, and the hope is that they heal quickly. But what about a lack of blood flow? When blood flow is disrupted in an area, wounds can happen because tissue breaks down if insufficient blood flow keeps the skin alive in a particular area (1).

When lack of blood flow is an issue, we usually talk about poor arterial circulation in an area. Patients may do well for a while as long as their skin is intact and there is no trauma, but with impaired arterial flow, as with atherosclerosis, the tissue will not survive indefinitely. It may break down on its own. Blood vessels can become compressed, such as with a hematoma, where an extensive collection of blood forms under the skin from blunt force trauma or surgical bleeding issues. The hematoma enlarges and compresses arteries under the skin, decreasing blood flow. In Ms. E’s case, severe edema due to muscle ischemia led to severe edema. The skin then may start to die, leading to breakdown and wound development, or may require a fasciotomy to relieve pressure and save the muscle from certain death.

Ask yourself...

- It’s common to take care of patients with primary closure wounds. Have you seen wounds heal by granulation?

- What problems did you encounter with patients with this type of wound healing? How long did these wounds take to heal?

- What may be happening to cause impaired blood flow leading to wounds? What other complications can occur where there is insufficient blood flow?

- What is the difference between a clean and a clean-contaminated wound?

- What is the difference between a dirty and a contaminated wound?

Arterial Ulcers

Arterial ulcers can develop and be very challenging to heal. Arterial ulcers have a characteristic “punched out” appearance and are pale at the base, indicating the lack of blood flow; additionally, they tend to be dry at the base with little moisture. Usually, they are very painful for the patient, partially due to the location over a bony area and the lack of blood flow. Arterial ulcers can also present as wet or dry gangrene (1). Though Ms. E’s wound is not currently classified as an arterial wound, it started as a result of a lack of blood flow in her extremity. The restoration of blood flow saved her from an amputation.

Venous Ulcers

Another type of ulcer that can develop is a venous ulcer. Venous ulcers develop due to longstanding venous insufficiency, which happens when valves fail or become incompetent in the lower extremities. Venous ulcers have a ruddy appearance and very irregular edges. They produce a large amount of drainage or exudate. If they have been present for a long period, these ulcers can range from extremely painful to little sensation (1, 2).

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever fallen asleep on your arm or leg and felt the pain of the lack of circulation when you woke up?

- Consider the pain in an extremity where blood flow cannot be restored simply by moving the extremity and readjusting its position.

- Have you ever cared for arterial and venous ulcers? What care did you provide? How did the patient respond?

- What is the difference between an arterial and a venous ulcer?

- What causes venous ulcers?

Neuropathic Ulcers

Although neuropathic ulcers are typically found in patients who are diabetic, not everyone who develops neuropathy is diabetic. However, their cause is the same – lack of sensation in the area, usually the foot. They can occur anywhere on the foot but are more common over bony areas and most often happen because of friction and repeated trauma in the area. There are usually calluses in these areas, as calluses are responses to repeated trauma. The body tries to protect the underlying tissue by becoming stiff and thick. When the body does not feel this happening, it leads to additional trauma and tissue breakdown. Think of putting a rock in your shoe and walking on it all day. You would know that damage was occurring. These patients are experiencing this, but don’t feel it because they have lost sensation in the foot.

These ulcers are usually round and can be shallow or deep depending on the trauma to the underlying tissue. Often, the depth is unknown until the wound’s surface is removed to reveal the extent of the wound. The perimeter of these wounds may be made up of hard callus. The base of the wound may be pale if arterial disease is present, or it can be a beefy red tone (1).

Ask yourself...

- What pressure injury prevention methods are needed for the patient who spends most of their time immobilized?

- What medical equipment may help in these endeavors?

- What challenges may present when a patient no longer has sensation in the feet? How do you address these challenges?

- Have you witnessed a wound that is healing well but suddenly stops progressing? What causes a wound to heal normally and then stop progressing?

- What might be going on with the patient?

Pressure Injuries

Pressure injuries (previously called pressure ulcers) occur as a result of pressure to an area of skin, resulting in injury to deeper structures. Immobility is a common cause of pressure injuries. They are usually present over bony prominences and are caused by pressure against a bed or wheelchair. This reduces circulation to the area and may cause tissue death if the pressure is not relieved. Friction can also contribute to pressure injuries, such as when sliding up in bed or using a heel to push up in bed. Pressure injuries may result in deep tissue death and are classified in stages from one to four (1, 2).

- Stage 1 is characterized by erythema that does not blanch with pressure.

- Stage 2 is indicated by partial skin thickness tissue loss with a shallow opening and a red wound base.

- Stage 3 ulcers show full-thickness tissue loss with exposed subcutaneous tissue.

- Stage 4 ulcers reveal exposed bone, tendon, and muscle tissue

There is no designated timeline for wound healing, and there is no determination of when a wound is to be labeled as chronic or acute; however, generally, wounds that don’t heal within a few weeks tend to be viewed as chronic. Ideally, wounds should decrease in size by 50% in the first four weeks. If this is not the case, there is more than likely something causing the delayed wound healing. Wounds should show signs of healing with every passing week, and if they aren’t, an investigation into why should be started (1).

Ask yourself...

- What pressure injury prevention methods are needed for the patient who spends most of their time immobilized?

- What medical equipment may help in these endeavors?

- What challenges may present when a patient no longer has foot sensation? How do you address these challenges?

- Have you witnessed a wound that is healing well but suddenly stops progressing? What causes a wound to heal normally and then stop progressing?

- What might be going on with the patient?

Case Study (continued)

Ms. E’s wound was large, measuring over 26 cm in length and 11 mm in width. She had an exposed tendon in the wound. Due to the size of the wound and the edema that led to large amounts of exudate, she was placed on negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) from the beginning of her treatment. She developed significant skin excoriation initially due to exposure to large amounts of drainage. She was not adherent to the plan of care, which required her to keep the leg elevated to help control edema, and edema was a significant contributor to the lack of healing. The decision was made to begin treatment with a skin substitute to improve wound healing chances. The product chosen for her was an acellular “fish skin” dressing. We’ll talk about this product later.

Ask yourself...

- Thinking back to Ms. E’s history, what else may be causing the wound’s lack of progression besides edema?

- What additional education would be beneficial to provide to this patient?

- Have you ever seen a skin substitute used? What was the patient’s response?

- What additional assessments would be beneficial to complete for this patient?

- The patient asks you if this wound will heal quickly. How would you respond?

Normal Wound Healing Phases

Before we look at what hinders wound healing, let’s look at the normal healing process.

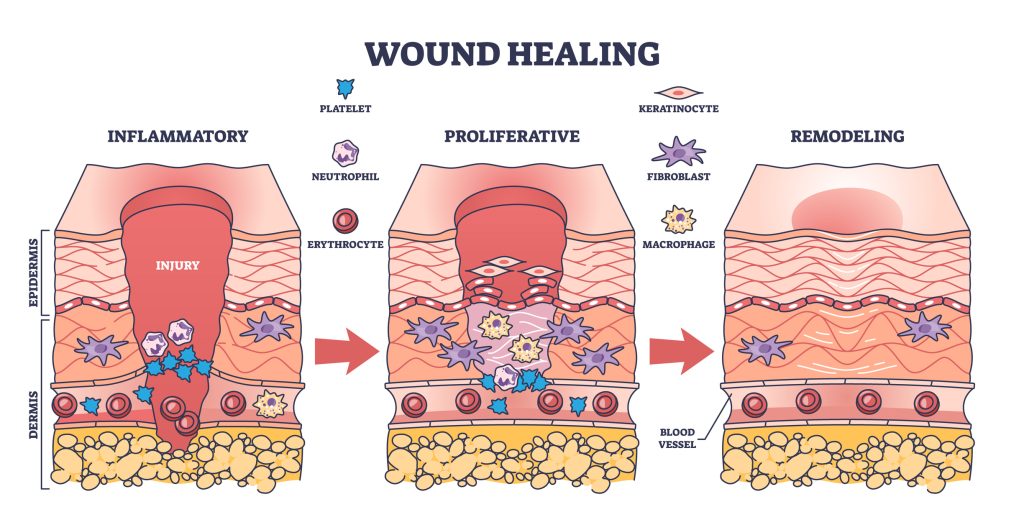

Inflammatory Phase

The initial phase of wound healing is known as the initiation or inflammatory phase; usually, it lasts one to five days. Upon injury, the vessels in the skin will constrict to provide for hemostasis and limit bleeding. The clotting cascade is triggered after the platelets begin to aggregate or clump together; this sets up the release of growth factors and plays a vital role in wound healing progression. A fibrin matrix will form as the basic structure around which the wound can heal. Pressure may be needed to control bleeding if the wound involves larger vessels. In some cases, other agents may be required to produce hemostasis and control bleeding (1, 2).

We may think of inflammation as a sign of something wrong, but this is a part of routine wound healing. This phase does not produce a strong wound and is usually complete in around three days unless the wound becomes infected or something else interferes with the healing process. This phase includes macrophage development, degranulation of mast cells, and histamine release, which causes vasodilation. This is the phase where swelling may be seen and occurs due to the permeability of the vessels from the cellular mediators that are present.

Epithelialization Phase

The next phase of wound healing involves epithelialization. In this phase, basal and epithelial cells work to develop a fibrin network of similar cells; this process stops when the dermal layer of cells is rebuilt. This process may take as little as 48 hours in a surgical wound. This layer forms a protective coating to help keep out bacteria and foreign bodies. This layer is fragile and can be easily broken with trauma to the wound if a wound is not primarily closed, where the edges are brought together and closed.

Wounds that heal by secondary intention take longer, as the epithelial cell migration must reach a larger surface area. In these wounds, a substance known as biofilm can develop. Biofilm is produced by bacteria that bind to the wound base, leading to ongoing inflammation and impairing the epithelialization process. Epithelial cells may also become inactive, making them unable to replicate. They cannot proliferate or reproduce rapidly, impairing healing (1, 2).

Proliferation Phase

The next phase of wound healing is the stage of fibroplasia or proliferation. This phase can last from two to 20 days. In this phase, fibroblasts will proliferate, ground substance accumulates, and collagen will be produced. Fibroblasts are usually present in the wound in the first 24 hours. They work by attaching to the clot’s fibrin matrix and producing myofibroblast proteins. These are typically present in the wound by the fifth day. The ground substance comprises glycoproteins, mucopolysaccharides, electrolytes, and water. The process of apoptosis (programmed cell death) leads to the loss of the myofibroblasts as the wound forms a scar.

Fibroblasts also form collagen and continue for up to six weeks following a surgical wound. This stimulates angiogenesis, or the formation of new blood vessels. The combination of collagen production and angiogenesis leads to granulation tissue formation. When there is abnormal fibrosis, extensive scarring can happen and lead to a keloid; this may be visible in the wound during the healing process as hypergranulation tissue (1, 2).

Remodeling Phase

The final phase of wound healing is that of a mature wound and is sometimes called the remodeling phase. This phase of healing can extend from 21 days to months or years. The final strength of the wound will be related to the collagen present in the wound. Collagen will need to cross-link and remodel for the wound to mature. About 80 percent of the original tissue strength is present in a surgical wound in 6 weeks. The wound, however, will continue to heal for up to 180 days. This skin may get stronger, but never regain its full, previous strength. Factors that influence the final strength include the severity of the initial wound and any delay in wound healing. Some wounds stay in the remodeling phase for years following surgery or trauma (1).

Ask yourself...

- What type of wounds have you witnessed that have progressed normally?

- Can you recall the wound passing through the stages we have just discussed? Did those wounds heal primarily or secondarily?

- What is the proliferative phase of wound healing?

- How are the inflammatory and epidermal phases of wound healing different?

- What is a sign that the wound has healed?

Impaired Wound Healing

Many factors can contribute to poor wound healing. Knowing the risk factors for impaired wound healing and how to address them will help speed up the healing process and shorten the time a patient has to contend with an open wound. Let’s look at some of the factors that may occur and how each one may be treated to reduce the time it takes for a wound to heal.

Impaired Wound Healing Contributing Factors: Blood Flow

A wound cannot heal without proper blood flow. Think about all those chemical mediators that are a part of normal wound healing that we have just discussed. They arrive in the tissues via circulation carried in the blood along with oxygen. Oxygen-deprived tissue will not heal, and the lack of blood flow also affects the removal of metabolic waste products. No matter where a wound is located, it will not heal if there is insufficient blood flow.

This may require intervention to restore blood flow, such as a bypass, endarterectomy, angioplasty, or stenting for wounds located on an extremity; this may be necessary in the arterial wound or in the diabetic/neuropathic ulcer. Atherosclerosis is common in patients who are diabetic. Patients who complain of pain, tiredness, cramping, or a “giving way” sensation when walking may be experiencing claudication, which occurs when the demand for blood in the extremity muscle cannot be met due to impaired blood flow in the extremity.

When wounds are already present, there is an even greater need for blood flow. Rest pain occurs when there is insufficient blood flow at rest in the extremity. This patient’s wound can progress to ischemia quickly and will need urgent restoration of blood flow to heal the wound. Patient education involves teaching the patient to protect the limb from injury and reporting any signs of worsening circulation, including increased pain, color changes in the extremity, wearing proper footwear, and never going barefoot. They will also need help modifying the risk factors associated with the development of arterial disease (2, 3).

Ask yourself...

- What critical issue must be resolved for a wound to have a chance to heal?

- Have you taken care of the patient with PAD?

- What changes are present in the lower extremities besides pain that can give clues that PAD might be present and contributing to poor wound healing?

- Thinking about our case study, what risk factors does she have that need to be managed to keep her disease from progressing and leading to problems again in the future?

- What education can you provide to help patients understand wound healing?

Impaired Wound Healing Contributing Factors: Infection

An infection will impair wound healing at several steps. If bacteria are in the wound, the inflammatory phase of wound healing is impaired, preventing epithelialization from occurring; cells may die, increasing inflammation in the wound. Necrotic tissue will develop and hinder new tissue from forming. The formation of necrotic tissue can also lead to further bacterial growth in the wound, resulting in a cycle of non-healing.

Think back to the types of surgical wounds we talked about earlier; the degree of contamination of a surgical wound at the time of incision will play a role in ongoing infection. The presence of cellulitis or skin infection can slow the healing process of the wound. This is a common occurrence with venous ulcers due to edema, which allows bacteria to enter microscopic tears in the skin. Burn patients are at high risk of infection, especially if a lot of skin is lost. Thermal injuries may be accompanied by an immunosuppression response as well.

The nurse’s role in educating patients about keeping wounds as clean as possible is critical to preventing contamination in the home. Educate on keeping the wounds covered and avoiding contamination by pets when changing bandages. A wound should have purulent material (cloudy fluid) to be classified as infected. A positive wound culture in a wound that was primarily closed and has reopened indicates infection. Infection may be superficial or involve deep infection into an organ or wound space. These wounds will require treatment with antibiotics. Cultures are only obtained in chronic wounds if they have signs of infection, such as heavy purulence or excessive drainage, and other signs of illness, such as cellulitis around the wound. Random cultures will be positive for bacteria once the wound becomes chronic, as there will be microbes in all wounds, but not all wounds are considered infected. Cultures should always be obtained following debridement (discussed later) to penetrate the biofilm, yielding more accurate results. Excessive use of antibiotics can lead to resistant bacteria and the development of allergies (2, 3, 4, 5).

Impaired Wound Healing Contributing Factors: Smoking

Smoking has been linked to surgical site infections but may also interfere with wound healing by other mechanisms. Some of these mechanisms are not fully understood. Nicotine has been presumed to be the major contributor to the impairment, but more recently, the compounds in the smoke are believed to play a role. The Department of Health and Human Services states that there are over 7,000 chemicals in tobacco smoke. Some include carbon monoxide, arsenic, hydrogen cyanide, formaldehyde, benzene, lead, and mercury. Look up some of these chemicals to learn more about what they do in the human body over time.

Multiple factors are to blame for the detrimental effects of smoking, but the vasoactive effects of nicotine, which lead to ischemia by vasoconstriction, will also reduce the inflammatory response. This alters the destruction of bacteria and collagen metabolism. These effects lead to wound dehiscence as well as incisional hernias. Studies have shown that smoking cessation for as little as four to eight weeks before surgery can improve wound healing and decrease surgical site infections. Of note, smoking can reduce blood flow by up to 40%, with the effects lasting up to 45 minutes. For patients who smoke a pack a day or more, this can certainly add up to a significant reduction in blood flow to vulnerable tissue. Studies using nicotine replacement therapies (NRT) for tobacco cessation have not shown these same effects. NRT in combination with other methods may be helpful in patients with wounds to help them stop using tobacco. Patient education regarding these effects is critical in gaining the patient’s participation in promoting their wound healing (2, 3, 5, 6).

Ask yourself...

- Think about the chronic wounds you have witnessed. Did you see signs of infection?

- Should all bacterial wounds be treated with antibiotics? What options may need to be considered when a patient, such as Ms. E, has allergies to the antibiotics needed to treat her wound infection?

- What education should you include when teaching patients taking antibiotics for wound infections?

- What smoking cessation resources are available at your facility?

- What is wound debridement?

Case Study (continued)

Ms. E’s care presents many challenges, but the significance of her tobacco use is a big contributor to the stalling of her wound’s healing. With encouragement at every office visit, she has eventually gotten to one pack a day but shows little interest in eliminating tobacco use. This is one of the greatest challenges in wound care because the patient must see the need for the modification of this risk factor. Tobacco cessation not only involves the withdrawal from a powerful chemical in the body, but also helps the patient with the habit and things they do associated with lighting up a cigarette. Unless Ms. E decides she wants to stop smoking, this barrier to wound healing may never be resolved.

Impaired Wound Healing Contributing Factors: Aging

The aging process affects the skin as nerves and blood vessels decrease. The layers of the skin will also thin with age, from the dermis through to the basement membrane. There is a loss of collagen, and the ability to produce collagen decreases as well, leading to slower healing and wound breakdown from infection. Unfortunately, this is a risk factor that cannot be changed. In older patients, education must be provided to help change the risks that can be modified (2).

Impaired Wound Healing Contributing Factors: Nutrition

Nutrition plays a vital role in wound healing. Proper nutrition should ideally come from the diet, as there is not much evidence supporting the use of dietary supplements. Supplements used with some success include zinc and vitamin C. Encouraging increased protein intake may also aid in wound healing (2, 3).

Impaired Wound Healing Contributing Factors: Immobilization

Prolonged immobilization increases the risk of wound development, especially pressure wounds. In some wounds, immobilization can help with wound healing, such as boots and casts for foot ulcers. Patients should be instructed on the importance of position changes to prevent pressure areas on the back, sacrum, and heels, where pressure ulcer development is common (2, 3).

Impaired Wound Healing Contributing Factors: Diabetes

Diabetes has long been known to harm wound healing. There are many ways that diabetes impairs wound healing at the cellular level:

- Reduction in growth factors

- Decreased angiogenesis

- Decreased macrophage production

- Decreased collagen synthesis

- Impaired function at the epidermal layer, including the number of nerves

- Decreased granulation tissue

- Decreased fibroblast migration and proliferation

- Decreased bone healing

- Lack of balance between extracellular matrix components and remodeling by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)

Diabetes contributes to the development of neuropathy and vascular disease from atherosclerosis. Both conditions increase the chances of infection and delayed wound healing. Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) with neuropathy leads to the development of foot ulcers and can lead to limb loss from a lack of healing. The loss of sensation from neuropathy leads to unawareness of injury and loss of pain perception.

Patients with diabetes may develop bony changes of the toes and midfoot, and collapse of the foot arch. These bony changes and the loss of sensation lead to skin breakdown from improper footwear in weight-bearing locations. Loss of autonomic nerves leads to dry skin that is more susceptible to breakdown and tearing as the patient loses sweat and oil gland function. Patients must be provided education on controlling diabetes and the importance of foot care, including daily foot examination and proper footwear that is replaced annually.

Ask yourself...

- What are other methods that can help tobacco smokers quit?

- What issues can occur in the aging patient with a poor appetite who is also immobilized? What additional education might be necessary for these patients?

- How does diabetes complicate wound healing?

- Does your facility have a diabetic educator? How can they help educate a patient with diabetic wounds?

- How do bony changes impact patients?

Case Study Update

Due to her diabetes and constant hyperglycemia, Ms. E has had infection issues that have required treatment. Due to her COPD exacerbations and pneumonia, she has needed multiple rounds of steroids, which have contributed to her lack of diabetes control. Her A1C is now 12, and her blood sugar runs in the 250-300 range most days. Ms. E often says, “I know I don’t eat like I should.”

Impaired Wound Healing Contributing Factors: Venous Disease

Venous insufficiency contributes to the development of venous ulcers due to a lack of venous return to the heart; this creates a pooling of blood in the lower extremities, leading to skin changes. Venous insufficiency results from a failure of or lack of valves in the vein, leading to chronic edema and skin changes resulting from hemosiderin deposition (explained below). Valves should open and close with each heartbeat, but when they become incompetent and don’t close properly :

- Blood flows backward or in a retrograde fashion, causing pooling in the affected lower extremity.

- Hemosiderin develops from red blood cell breakdown in the tissue where blood has leaked from the vascular compartment into the subcutaneous tissue, leaving a brownish stain on the skin when the red blood cells break down and weaken the skin.

- Itching develops, and scratching leads to trauma that initiates breakdown.

- The skin becomes dry and scaly.

- Breakdown may occur due to extensive edema, which causes the skin to tear. It may begin with the weeping of the skin due to the stretching but ultimately leads to an ulcer.

- Edema can occur, which is caused by fluid accumulation in the interstitial tissue and leads to changes in skin integrity. This increased interstitial pressure changes how the cells and capillaries function, further delaying the healing process.

- Skin in the lower leg can become fibrotic and is at high risk for injury.

Reduction in these risk factors begins with elevation and compression. When the patient is sitting, teach them to elevate the legs above the level of the hips. If they are lying down, the legs should be above heart level. Leg exercises with flexion and extension of the ankles will help to activate the calf muscle pump and aid in venous return to the heart. Skincare is critical to promote healing venous wounds and to prevent a recurrence. Some patients may need topical steroids for stasis dermatitis. Regular moisturizer use is also essential in this patient and should be fragrance-free. In addition to elevation, compression will help overcome some barriers to wound healing when edema is present. Compression should fit firmly, with the tightest compression at the ankle.

Impaired Wound Healing Contributing Factors: Immunosuppression

Immunocompromised patients may experience delayed wound healing due to the decreased inflammatory healing phase. They are also at risk for chronic wound development and wound infection. Immunocompromised patients include those on systemic steroid therapy with conditions such as transplants, rheumatoid arthritis, pulmonary disease, or other connective tissue disorders. Steroids can slow the inflammatory phase of wound healing and keep it from progressing through the normal stages of healing. Conversely, some topical steroids have been used with some success to treat chronic wounds.

Patients on chemotherapy may experience delayed wound healing due to effects on vascular endothelial growth factor. This factor plays a role in angiogenesis in the early stages of wound healing. Unfortunately, this factor is a target for cancer therapy. Chemotherapy is also known to lead to neuropathy, which places a patient at higher risk for loss of sensation. Radiation therapy can also produce delayed wound healing, especially when administered in an area of a recent incision or in the skin where an incision may need to be placed.

These wounds are more likely to develop complications. Radiation causes ischemic changes in the skin and may lead to ulcers that take a very long time to heal. Patient education for these patients involves ensuring they eat a well-balanced diet to provide proper nutrition and keep their skin moisturized. This may be challenging for chemotherapy patients; protein supplements may be needed for nutrition (3).

Impaired Wound Healing Contributing Factors: Obesity

Delayed wound healing in obese individuals is related to many factors. The additional adipose tissue reduces vascular flow, as fewer vessels are found in the subcutaneous tissue. Wound tension is increased. Decreased perfusion to the skin increases the susceptibility to pressure injuries. Patients may also be less mobile and unable to change positions frequently. They are also at higher risk of skin friction when moving. Counseling patients regarding diet and exercise is vital, but patience is paramount as weight loss is slow (3).

Wound Assessment

History and Physical

Wound assessment begins with a complete history and physical exam. What do I need to know about this patient to help me understand why they have a wound and how to treat it? The following questions in the assessment process will help you determine a treatment plan.

- When did it start?

- What happened to lead to the wound?

- What is the patient doing currently to treat the wound?

- What has been tried before?

- Is there pain? Is there no pain?

- Is this a wound that went away and came back?

- What healed the wound last time?

- What other medical conditions or risk factors are present that may impact healing?

- Do they smoke?

- Do they have help to care for themselves?

- Are they ambulatory, or do they need assistive devices?

- Do they work?

- What is their surgical history?

- What diagnostic studies have been performed?

All of this information will help in knowing how to proceed and educate the patient as the process moves forward (5, 8).

Wound Examination

Look at the wound and determine the condition of the bed, size of the wound, and condition of the skin around it. Is there an infection? For a surgical wound, are the edges together leaking or red? Documentation should include measurements that include length, width, and depth in centimeters—document how the wound is measured. For example, like a clock face, use the head as 12:00 and measure the length in this dimension and the width from 9:00 across to 3:00.

Measure in the same plane every time the wound is measured. This is especially critical if you are not the only person who will see the patient at every visit. Depth should include the depth from the wound’s surface to the bottom and any undermining or tunneling found in the wound. Looking at the wound edges and the surrounding skin will help guide the management of the wound itself. Wound edges may have a rolled-up appearance or contain calluses. If the documentation system allows, “a picture is worth a thousand words” (8).

Describing the Wound

This can be challenging unless you know what all the words mean, so let’s break it down to make it easier to understand. These terms will give those who read the documentation a good picture of what is going on with the wound and help guide the choices made for management and wound healing (9).

- Exudate/maceration/purulence: drainage/white areas due to excessive moisture on the skin; thick yellow exudate indicating infection

- Slough: thick yellow tissue that slows wound healing and needs to be removed by debridement

- Necrosis/Eschar: dead tissue over a wound that may hide the true extent of the wound

- Erythema/Induration: redness around the wound and hardened tissue associated with an increase in fibrin and inflammation

- Undermining/tunneling: tissue under the wound edges that becomes eroded; channels that extend deep into a wound

- Granulation tissue: new tissue with microscopic blood vessels and connective tissue

- Hypergranulation: excessive granulation tissue formation beyond the edges of a wound

Wound Management

We previously discussed what delays wound healing, so let’s review the mandatory requirements. For a wound to heal, it must (8, 10):

- Have adequate blood flow.

- Be clear of necrotic tissue and slough.

- Be infection-free and keep moist.

When a wound becomes chronic, the wound care changes. Choosing the proper wound dressing aids in the healing process. Dressings are selected with the following in mind (8, 10):

- Dead space must be eliminated

- Exudate must be controlled

- Bacterial overgrowth should be minimized

- Proper fluid balance should be maintained

- Protection is provided, and bacteria are kept out

- Costs must be contained

- Dressings must be manageable for the patient/caregiver/nurses, including reduction of pain and fewer changes.

Wound Management: Medical Management

We have already talked about factors that affect wound healing, but let’s dive a little deeper to discuss managing a few of those things. Managing infection is key to ensuring that healing will continue once a wound has developed. If you could put every wound under a microscope, you would see bacteria in every open wound. They live everywhere, and we can’t keep them out of the wound, but remember that every wound is not infected, and antibiotic therapy should be reserved for the wound showing other signs of infection.

Indications of a wound infection include purulent drainage, odor, cellulitis, fever, chills, and difficulty controlling blood sugar. Advanced signs include hypotension, osteomyelitis, and nausea. Infection treatment may begin empirically, using an antibiotic that would most likely target the bacteria suspected in the wound. Ultimately, the antibiotic therapy should be based on culture results so that any unusual bacteria may be detected and treated appropriately. Targeting bacteria with culture results helps to reduce the development of resistant bacteria. Infection treatment has become much more challenging in recent years due to the development of resistance. It’s critical to use good stewardship with antibiotics to help control resistance (10).

Managing blood sugar will be of utmost importance if the patient is diabetic. Out-of-control blood sugar will hinder wound healing and predispose the patient to infection. Remember that challenges with blood sugar control in a patient whose blood sugars have been relatively well controlled may be a sign of infection and should be followed up. Encourage patients to check their blood sugar regularly during wound management. This will help them to see what is happening and correct any issues they may have with wound healing related to diabetes. Hemoglobin A1C changes slowly, so help them understand that they need to know what is going on with their blood sugar daily to catch any issues early (10).

Ask yourself...

- A patient’s A1C last week was 9, and his diabetic foot ulcer has almost stopped showing any signs of progress. What education does this patient need while trying to get this diabetic foot ulcer healed?

- What other steps may be needed to determine why the wound is not healing?

- What contributed to the rise in Ms. E’s A1C from 10.7 to 12 over the six-month period of wound care she has been undergoing?

- What types of documentation does your facility require when assessing wounds?

- What is slough?

Wound Management: Debridement

One thing that will deter a wound from healing is the presence of devitalized tissue (or tissue in the wound that builds up on the surface of the wound, also known as slough). Devitalized tissue comprises fibrin with some dead cells and leukocytes and can develop into necrotic tissue. This buildup can lead to biofilm and will stop a wound dead in its tracks. This type of wound needs angiogenesis to get the new tissue to form; biofilm won’t let this happen.

The biofilm is a bacterial overgrowth that forms on the surface of the wound. To keep the surface of the wound fresh and moving forward toward healing, serial debridement is needed. Think of this chronic wound as sluggish because slough and necrosis make the body lazy, and it thinks, “Wow, I don’t have to work so hard now.” Debridement wakes the wound by telling it there is more work to do, and now it thinks, “Hey, we have an acute wound, let’s get going. We have a new wound to get healed,” (8, 10).

Debridement is usually done with a sharp instrument, but enzymatic products can be used for extensive sloughing in a patient who may not tolerate sharp debridement. Sharp debridement removes excess slough and necrotic areas and keeps the wound’s edges fresh so they continue granulating toward the center for healing. Debridement prepares the wound for dressing and biologics that may be needed to speed wound healing. Dealing with the wound includes irrigation to remove loose tissue from the surface, which also helps remove bacteria.

This can be done with a syringe and saline or with a pulse lavage device if available. Typically, saline is the solution of choice. Some commercial preparations are available in a pump spray bottle as well. For patients with painful wounds, some clinicians (this author included) use lidocaine gel or another topical anesthetic in the wound to provide anesthesia before debridement and help the patient tolerate the procedure. For wounds that are insensate (numb), such as diabetic foot wounds, no topical agent is needed (8, 10).

Case Study (continued)

Ms. E began undergoing serial debridements early in her post-op course. They were done in the office and initially with the aid of a topical anesthetic to help with pain control. As the process went forward, she no longer needed an anesthetic. This may happen due to tolerance of the procedure or lack of sensation in the newly formed tissue. In this case, it was most likely due to the beginning of the use of the skin substitute, which covered the open nerve endings in the base of the wound. This is seen frequently in the author’s practice when using skin substitutes.

Due to the size of the wound, a fish skin dressing was placed to try to decrease the time it would take to heal this huge wound. This skin substitute was applied weekly in the office, and NPWT was placed over the wound. She did not require dressing changes outside of the office as the dressing was left in place for the full week between visits. Due to her lack of adherence to the plan of care and continuing to engage in activities that she was counseled against, there were significant issues with keeping the dressing in place, further slowing the healing process. When the NPWT was not in place, the wound was exposed to too much moisture from excessive exudate, causing maceration of the lower half of the wound. Fortunately, she ultimately got better at keeping the dressing in place.

Ask yourself...

- What techniques can be used to help patients tolerate wound debridement?

- What can be done ahead of time to prepare patients for debridement?

- What other advantages may exist for patients who receive dressing changes weekly in the office?

- What is a fish skin dressing?

- Does your facility use wound ostomy nurses? How do they help manage wound care?

Wound Management: Treating Dead Space

In wounds that have cavities known as dead space, it is vital for these areas to be filled to absorb any fluid in the wound and provide an environment for ongoing granulation in the dead space. Traditionally, large cavity wounds have been packed with saline-moistened gauze to fill areas of undermining or tunneling and then covered with dry gauze. These dressing changes must be frequent to prevent the gauze from completely drying out; this may be as much as three times a day. If the wound is painful, this can be very traumatic to the patient. Unfortunately, this may also draw out granulation tissue and reinjure the healthy tissue forming in the wound. This technique should be used only for a short time in wounds with significant slough and necrosis. Once removed, the dressing should be changed to another regimen.

In cases where the wound is painful and frequent dressings are required, a permeable silicone dressing may be placed in the base of the wound and left in place up to seven days to decrease the gauze dressing’s adherence to healthy tissue. These dressings allow exudate to be absorbed and slough to be removed, but protect granulation in the base of the wound (8, 10).

A good option for large wounds with dead space is to use negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), if available. This therapy is especially valuable in extensive open wounds that have large amounts of exudate. NPWT has been shown to reduce edema in peri-wound skin and stimulate circulation in the wound, helping with angiogenesis and improving granulation tissue formation. The fluid draining from the wound is absorbed into a foam and suctioned into a container through a vacuum, which keeps excessive moisture away from the wound. Different types of foam are available to pack into smaller tunnels and areas of undermining.

This also reduces the number of times the dressing requires changing for painful wounds, as most NPWT treatments involve changes three times weekly. If the wound is extremely painful, the same silicone barrier used in the gauze dressing can be placed under the foam for NPWT. When using NPWT for treatment, patients should be made aware of the odor caused by the large amount of drainage. Reassure them that this is normal and does not necessarily indicate anything wrong with the wound (8, 10).

Wound Management: Other Medical Treatments

Other things that may be used for wounds include growth factors, iodine-based dressings, silver dressings, and honey. Growth factors may be platelet-derived, epidermal, or granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating. Cadoexomer iodine helps to reduce the bacterial load in a wound, provides a moist environment, and is used for short periods. Many dressings now can contain silver, known to be toxic to bacteria. Study results, however, have not shown this to be superior to standard therapy. Silver is still used as it may reduce contamination by bacteria on the surface of the wound.

Honey is probably the oldest known wound preparation, dating back to ancient times. It carries broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties due to its high osmolarity and because it is concentrated with hydrogen peroxide. Honey is not used in all wounds, but there are situations where it is very valuable, such as burns or small wounds that need moisture to keep the healing process moving forward. Topical beta-blockers are under study, but evidence supporting their efficacy is limited (10).

Some wounds may benefit from additional therapies such as hyperbaric oxygen, low-frequency ultrasound, electrical stimulation, electromagnetic therapy, and phototherapy. Not every location may have access to these therapies, but they may prove helpful in various types of wounds. Treatment of hypergranulation tissue may be needed and is usually done by a wound specialist. This may involve topical steroids or, in some cases, silver nitrate; these treatments are to be used with caution. Applying pressure to a wound may also aid in reducing hypergranulation tissue (10, 11).

Wound Management: Choosing the Right Dressing

There are many dressings to choose from when it comes to caring for a wound, and many are specific to each type. The first step in considering which dressing is best is to look for moisture control properties. Remember the wound you witnessed that was so wet the skin was macerated around the edges? That wound won’t heal because it is too wet. Or the wound that was so dry the dressing was stuck to the bottom? This wound won’t progress either. Gone are the days when the wound should be “left open to air.” Studies have shown that occluded wounds heal up to 40 percent faster. Theories as to why include leaving the wound in its fluid, which is rich in growth factors, and epidermal cells migrate more easily. This is truer in the acute wound than in the chronic wound. Depending on the size of the wound, occluded wounds may have less significant scarring (10).

So, the first choice is to look for something that will provide moisture balance and keep the excessive drainage away from the wound while maintaining a good moisture level. Remember, wounds need moisture balance. Most of these dressings allow for daily changes, reduce the time the wound is open, and help pain control for painful wounds. There is no ideal dressing, so looking at what’s available will help to determine what’s best for each type of wound.

Dressing Types

Wound dressing types include (12):

Open

This gauze dressing comes in many forms, from different-sized pads to different-sized rolls. It is inexpensive and can be used to pack large wounds, but it requires frequent changes.

Semi-Open

This category includes impregnated mesh gauze, such as petroleum gauze. It is inexpensive and easy to use. However, it does not control exudate or maintain moisture in the wound. It also requires frequent changes.

Semi-Occlusive

This category includes films, foams, alginates, hydrogels, and hydrocolloids.

Films allow oxygen in but will keep bacteria out. They are see-through sticky dressings, great for intravenous (IV) sites and donor sites for skin grafts. They maintain moisture and are transparent and self-adhesive. They do not absorb drainage and can lead to maceration if there is too much drainage in a wound. They should not be left in place as a wound becomes drier, as they may cause damage upon removal.

Foams are two-layer products, with a foam layer that lies against the wound and a backing to prevent drainage and bacteria from entering the wound. They can absorb fluid and conform easily to wounds, so they can be used as fillers for dead space. They are opaque and may need to be changed more frequently in heavily exudating wounds. They should not be used on wounds with little moisture, as they can further dry out a wound. Additionally, they can be used to treat skin tears.

Alginates are made from various forms of algae. In the presence of wound fluids, they form a gel that helps to cover and even pack a wound. Many forms of alginates help customize the dressing, such as pads, ropes, and beads. They are great for moderate to heavy wound drainage and can remain in place for several days. They require a secondary dressing to cover them and can dry out a wound that does not have enough moisture. Unfortunately, they also have an unpleasant odor when changing the bandage.

Hydrocolloids consist of a gel or foam with a self-adhesive film, creating a moist environment. When removed from the wound, they provide a gentle debridement and can be used for packing wounds in some instances. Unfortunately, they can create an odor and may need daily changes. Cadoexemer iodine falls in this category as well. This form of iodine disperses slowly so as not to cause tissue damage. It comes in a paste or sheet form that can be cut to fit a wound.

Hydrogels are made of synthetic polymers that are mostly water and come in sheets, gels, or foams. They can absorb or donate water to the wound. They are most often used for dry wounds and can give a cooling sensation to the wound, reducing pain. There are no significant disadvantages, but they have been shown to allow gram-negative bacteria to grow (10).

Ongoing Trauma

During the healing process, wounds are very susceptible to trauma as the fragile tissue works to epithelialize and granulate. Protecting wounds from trauma is critical. Venous wounds may itch, and the patient will likely want to scratch the wound and the peri-wound skin. Preventing scratching will help reduce bacteria on the skin and inhibit new ulcer formation in the skin, which is very susceptible to injury.

Diabetic ulcers are most common on the bottom of the foot; if they are not offloaded, they will have little chance of healing. Patients may need offloading shoes or other means of stopping the friction that walking creates on the bottom of the foot. Other options include Cam (controlled ankle motion) walkers, total contact casts, knee scooters, crutches, wheelchairs, and bed rest. Patients must understand that even a few steps can undo what the body has worked days or weeks to rebuild. Once the wound is healed, patients who are diabetics will need long-term use of proper footwear to prevent a recurrence (12).

Managing Other Issues

Other wound issues that may need management include (14):

Odor

Managing odors can be done through regular debridement to reduce the wound’s bacterial burden and charcoal dressings and soaks, such as acetic acid.

Bleeding

Bleeding may occur in malignant wounds, after debridement, or in patients on chronic anticoagulation therapy. Pressure on the wound is usually enough to stop oozing. Agents that provide hemostasis can be applied to the wound, or if the bleeding is more significant, silver nitrate, cautery, or infiltration with epinephrine may be used.

Itching

Itching is usually more common when the skin is dry or if dermatitis is present. Moisturizers and skin protection are key. In some instances, a topical steroid cream may be needed. Help patients understand that dry skin is not healthy and can break down, leading to bacteria’s entry, resulting in cellulitis.

Pain

Pain control is critical to helping patients follow the medical regimen and tolerate dressing changes. Teach patients to take pain medications before dressing changes. Topical anesthetics may also help during debridement.

Edema

If edema is not controlled, the wound will have difficulty healing. Other options aside from general compression stockings should be selected with a wound present, such as zinc-impregnated compression stockings or two-layer compression wraps. Most patients can use any of these over the bandage. Elevation must also be used with compression to gain the full benefit of medical management. A good rule to remember is “toes above the nose” (author quote) to get the maximum benefit from elevation. This is sometimes a challenge for the patient with COPD, CHF, obesity, or any condition that prohibits them from reclining far enough to get the legs high enough to decrease edema (12).

Wound Management: Surgery

Some wounds will require surgical management to get them back on track. Extensive debridement may be necessary to remove deep infection, gangrenous areas, devitalized or infected bone, or foreign bodies. Patients who cannot tolerate sufficient outpatient debridement or require bone biopsy may also need operative debridement. If blood flow is an issue, revascularization will be necessary. For diabetic foot wounds, surgery may be required to correct bony abnormalities. Venous ulcers may need surgical ablation to reduce pressure related to venous insufficiency for the ulcer to heal. Some wounds, such as pressure injuries, may be large enough to require skin or muscle flaps to close. A diverting colostomy may be necessary if pressure injuries are exposed to fecal material (10, 14).

Ask yourself...

- What elevation methods may be used for patients with medical conditions that hinder them from lying flat?

- What wounds tend to be the most painful?

- What can cause a wound to develop an odor not present at the last assessment?

- What is the difference between open and semi-open wound healing?

- What is the difference between semi-occlusive and semi-open wound healing?

Conclusion

Wound care is a challenging process, and nurses must consider many factors to promote healing in an optimal time. I hope you have learned at least one thing you did not know about wound care, and what you have learned will make the next complex issue you have with your wound care patients easier.

References + Disclaimer

- Armstrong, D. (2020, July 20). Basic principles of wound healing [Review of Basic principles of wound healing]. Www.uptodate.com; Wolters Kluwer. Accessed 3/14/2021.

- Nettina, S. M. (2019). Lippincott manual of nursing practice. Wolters Kluwer.

- Armstrong, D. (2020, February 12). Risk factors for impaired wound healing and wound complications [Review of Risk factors for impaired wound healing and wound complications]. Www.uptodate.com; Wolters Kluwer. Accessed 3/14/2021.

- Anderson, D. (2019, December 18). Antimicrobial prophylaxis for prevention of surgical site infection in adults [Review of Antimicrobial prophylaxis for prevention of surgical site infection in adults]. Www.uptodate.com; Wolters Kluwer. Accessed 3/19/2021.

- Armstrong, D. (2021, February 22). Clinical assessment of chronic wounds [Review of Clinical assessment of chronic wounds]. Www.uptodate.com; Wolters Kluwer. Accessed 3/24/2021.

- (n.d.). Know the real cost of cigarettes [Review of Know the real cost of cigarettes]. Retrieved March 21, 2021, from https://therealcost.betobaccofree.hhs.gov

- (n.d.). Therapeutic shoes and inserts [Review of Therapeutic shoes and inserts]. Retrieved March 21, 2021, from https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/therapeutic-shoes-inserts

- Bishop, A. (2021). Wound assessment and dressing selection: an overview. British Journal of Nursing, 30(5), S12–S20. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2021.30.5.s12

- Mahoney, K. (2020). Part 1: wound assessment [Review of Part 1: wound assessment]. JCN, 34(2), 28–35.

- Armstrong, D. (2021, January 12). Basic principles of wound management [Review of Basic principles of wound management]. Www.uptodate.com; Wolters Kluwer. Accessed 3/14/2021.

- Mitchell, A., & Llumigusin, D. (2021). The assessment and management of hypergranulation. British Journal of Nursing, 30(5), S6–S10. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2021.30.5.s6

- Evans, K., & Kim, P. (2020, September 1). Overview of treatment of chronic wounds [Review of Overview of treatment of chronic wounds]. Www.uptodate.com; Wolters Kluwer. Accessed 3/29/2021.

- Shahrokhi, S. (2021, February 22). Skin substitutes [Review of Skin substitutes]. Www.uptodate.com; Wolters Kluwer. Accessed 4/7/2021.

- Berlowitz, D. (2020, May 12). Clinical staging and management of pressure-induced skin and soft tissue injury [Review of Clinical staging and management of pressure-induced skin and soft tissue injury]. Www.uptodate.com; Wolters Kluwer. Accessed 4/7/2021.

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback!