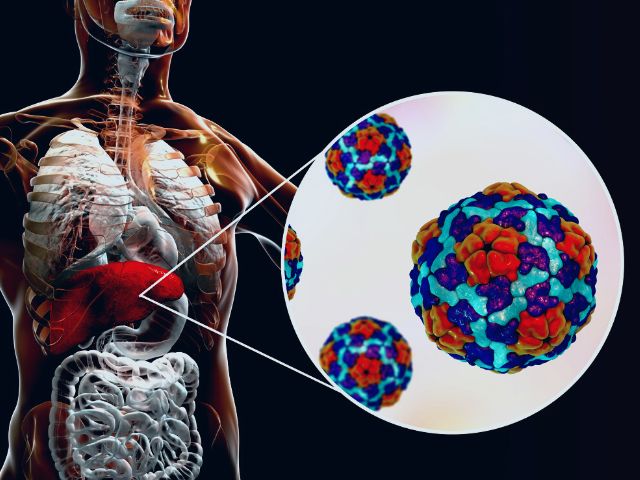

The liver performs many important functions including the formation of blood proteins that aid in clotting, transporting oxygen, and supporting one’s immune system.

The liver is also important in the production of bile, a substance needed to help digest food, and assists one’s body to store sugar (glucose) in the form of glycogen. Another important function of the liver is that it aids in ridding one’s body of harmful substances in the bloodstream, including drugs and alcohol and also breaks down saturated fats and produces cholesterol.

Hepatic failure occurs when one’s liver is not working well enough to perform these tasks and it can be a life-threatening emergency that requires immediate medical attention. It can be acute or chronic, leading to hepatic coma or hepatic encephalopathy