Course

2022 Florida Renewal Bundle

Course Highlights

- In this course we will cover all of the topics necessary for a Florida RN License Renewal.

- You will learn about the Florida Board of Nursing’s requirements, laws, and regulations, as well as helpful practice tips.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of topics ranging from domestic violence, human trafficking, vaping, and so much more.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 27

Course By:

Multiple Authors

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Florida Domestic Violence

Introduction

Domestic violence is defined as violent or aggressive behavior occurring within the home and usually involves the abuse of a spouse or partner. In the United States alone, it is estimated that more than 10 million adults have been subjected to domestic violence during the course of a year. This statistic translates to an incident of domestic violence occurring every 3 seconds. The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence [1] reports some daunting statistics:

- 1 in 3 women and 1 in 4 men have experienced some form of physical violence by an intimate partner.

- 1 in 4 women and 1 in 7 men have been victims of severe physical violence (such as beating, burning, strangling) by an intimate partner in their lifetime.

- On average, more than 20,000 phone calls placed to domestic violence hotlines nationwide.

- The presence of a gun in a domestic violence situation increases the risk of homicide by 500%; 19% of domestic violence involves a weapon; Most intimate partner homicides are committed with firearms.

- 1 in 15 children are exposed to intimate partner violence each year, and 90% of these children are eyewitnesses to this violence.

- From 2016 through 2018, the number of intimate partner violence victimizations in the United States increased 42%.

Due to the increasing prevalence of domestic violence in society, there is a high probability that all healthcare professionals will evaluate and treat a victim (and quite possibly a perpetrator as well) of domestic violence at some time during their healthcare career. The importance of ongoing education and global awareness cannot be understated.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemics’ stay at home/shelter in place orders resulted in spikes in calls to domestic violence hotlines. From layoffs and loss of income to decreased availability of shelters and backlogged courtrooms, fewer resources were made available to victims of domestic violence. These measures resulted in increases in both the incidence and severity of domestic violence. Sadly, the effects of this pandemic, especially on this issue, continue years later [2].

Forms of Domestic Violence

Domestic violence may encompass physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional and verbal abuse, and spiritual and economic abuse. Defined as a pattern of behavior used to gain power or control over an intimate partner, a domestic violence abuser may use tactics that frighten, intimidate, hurt, blame, or injure a person. These behaviors often escalate over time and intensity and have resulted, at times, in life-threatening injuries or death of a victim [3].

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is abuse or aggression that occurs in a romantic relationship. The term “intimate partner” refers to both current and former spouses and dating partners, including heterosexual and same-sex couples. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [4] further delineates IPV into four separate groups: physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, and psychological aggression.

- Physical violence may include hitting, kicking, and punching someone.

- Sexual violence may include using force to get a partner to partake in a sexual act.

- Stalking may include unwanted and threatening phone calls or text messages.

- Psychological aggression may include insults, threats, name-calling, or belittling a partner.

Teen Dating Violence (TDV) [5] is defined as dating violence affecting millions of teenagers annually. In addition to the threats from physical and sexual violence and other forms of aggression, TDV is often done electronically through repeated texting and placing sexual pictures of a person online without permission.

The CDC statistics on teen dating violence report:

- Nearly 1 in 11 female and about 1 in 15 male high school students report having experienced physical dating violence in the last year.

- About 1 in 9 female and 1 in 36 male high school students report having experienced sexual dating violence in the last year

- 26% of women and 15% of men who were victims of contact sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime first experienced these or other forms of violence by that partner before age 18.

Domestic violence transects every community and affects all people, regardless of age, socio-economic status, race, religion, gender, or nationality [6]. Whether the violence results in physical or psychological injury, the effects can last a lifetime and affect multiple generations.

Healthcare professionals are in a pivotal position to impact the lives of those affected by domestic violence positively. Oftentimes, they may be the first person to encounter a victim of domestic violence. Their ability to effectively evaluate the situation and provide time-sensitive, patient-centered care (including but not limited to treatment interventions, appropriate referrals, and follow-up care) can enhance immediate victim safety and reduce further injury, and improve the home front circumstances, moving forward.

Healthcare professionals must be able to identify and assess all patients for suspected abuse, and be able to offer treatment, counseling, education, and referrals, as appropriate. These referrals may extend out to shelter options, advocacy groups, child protection services and legal assistance [7].

Profiles of Victims/Abusers

Anyone can become a victim of domestic violence. Victims of domestic violence come from all walks of life, all age groups, all socio-economic groups, all religions, and all nationalities [8]. Violence can occur in any relationship when one person feels they are entitled to control another person through whatever means of abuse possible. This abuse is cyclical and usually increases in frequency and intensity. Victims of such violence report feelings of isolation, helplessness, guilt, anxiety, and embarrassment. They may become suicidal, start abusing drugs and alcohol, and feel that they have no one to turn to for help.

Although there isn’t a specific set of factors that result in “being a victim,” there are many thoughts as to what might affect a person’s active willingness to remain in a violent relationship. The following lists serve only as general guidance to inform the healthcare professional of possible underlying causes. Again, anyone can become a victim of domestic violence.

Victims of Domestic Abuse

There is no single “characteristic” or risk factor that automatically causes a person to become a victim of domestic violence. Instead, it may be a series of events that cause a person to become more vulnerable and enter and remain within an abusive relationship [9].

Domestic violence victims may have experienced violence during childhood, experienced total financial dependence on another person, or lacked basic social support (family and friends). These factors affect both the physical and psychological make-up of a person. Without intervention, these victims can develop personal esteem and confidence issues, further social isolation, economic dependency, and general feelings of insecurity. These effects may negatively affect the decision to stay in an abusive relationship.

Researchers [10] have found the following factors may place a person at a higher risk of becoming a victim of domestic violence, including (but not limited to):

- Poor self-image/ low self-esteem

- Financial dependence on the abuser

- Feeling powerless to stop the violence or leave the relationship

- Personal belief that jealousy is an expression of love

Common characteristics of victims of domestic violence include, but are not limited to:

- A history of abuse

- A history of alcohol or substance abuse (for themselves or their partners)

- Financial and family stressors- low income, limited family/friends contact, poverty status

- A member of an ethnic minority/ immigrant group; Limited English vocabulary

- Holds traditional beliefs that they should be submissive in a relationship

Reasons a victim may choose to stay in the relationship:

- A desire to end the abuse but not necessarily the relationship; they do love their abuser.

- Feelings of isolation and helplessness

- Fear of judgment if they reveal the abuse by seeking help.

- Feelings that they may not be able to support themselves if they leave their abuser; Fears for the safety of children involved in the relationship.

- Fear of backlash from community or family and friends/lack of knowledge of services available

- Strong religious/cultural belief system that reinforces staying in a relationship at all costs.

Abusers/Perpetrators of Domestic Violence

As with the domestic violence victim, there is no one set of traits to identify a domestic violence abuser/ perpetrator correctly. There are, however, some signs that may raise the red flag of suspicion when observed in a suspected domestic violence case.

The National Coalition on Domestic Abuse [11] has created a list of “red flag” indicators, including, but not limited to, the following:

- Extreme jealousy and possessiveness

- Verbally abusive

- Extremely controlling behavior

- Blaming the victim for anything bad that happens

- Control over all the finances in the relationship

- Demeaning the victim publicly or privately

- Humiliating or embarrassing the victim in front of other people

- Control over what the victim wears

- Abuse of other family members, including children (and even pets)

The following is a general list of indicators that help “may” identify a possible abuser [12].

- History of abuse within one’s family

- History of personal physical or sexual abuse

- A lack of appropriate coping skills

- Low self-esteem

- Codependent behavior

- Untreated mental illness

- Drug or alcohol abuse

- Socio-economic pressures related to the lower income status

- Prior criminal history

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Describe interventions/ resources currently available at your facility to assist a victim of domestic violence. What resources are currently available for domestic abuse perpetrators?

Initial Interaction and Screening Tools

Screening rates are as low as 1.5% to 13% among emergency and primary care physicians. The Academy of Medicine recommendation suggested that all women should be screened for sexual violence. Research found that healthcare providers working in emergency department only screened 20–25% of their encounters. As a result, this decreased opportunities for intervention, increased safety, and prevention of future violence [13].

Domestic violence (including Intimate partner violence) is an unfortunate cycle that may not be broken with a single emergency department visit; however, identifying and providing resources is necessary to make a difference, increase confidence and safety, and improve the overall health outcome for patients.

Compassionate, nonjudgmental screening by healthcare professionals affords the best opportunity for domestic violence victims to disclose their abuse. By recognizing signs of abuse and inquiring further, the nurse validates that the victim is worthy of care and confirms that the violence is a legitimate concern [14].

The screening for domestic abuse should be done in a private environment. Language interpreters, not family and friends, should be utilized if needed. Universal screening should be used; therefore, preventing any victim from being “singled out” and ensuring all potential victims are screened appropriately. All healthcare professionals should remain nonjudgmental and compassionate during the screening process [15].

During the interview process, assure the victim that all patients are screened for domestic violence. Be sure to include that DV affects many families and services are available to everyone who may be concerned about violence in their home.

An overview of domestic violence screenings follows. Links have been provided to an online copy of each screening tool.

Hurt, Insult, Threaten and Scream (HITS)

5 question screening tool assessing physical and verbal interactions with the partner; scores rank 1 (never) -5 (frequently); a score of 10 is considered positive.

- Physically hurt you?

- Insult or talk down to you?

- Threaten you with harm?

- Scream or curse at you?

- Force you to do sexual acts that you are not comfortable with?

http://www.ctcadv.org/files/4615/6657/9227/HPO_HITS_Screening_Tool_8.19.pdf

Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST)

8 question screening tool assessing physical, emotional, and sexual intimate partner violence.

http://womanabuse.webcanvas.ca/documents/wast.pdf

Partner Violence Screen (PVS)

3 question screening tool for interpersonal violence:

- Have you been hit, kicked, punched, or otherwise hurt by someone within the past year? If so, by whom?

- Do you feel safe in your current relationship?

- Is there a partner from a previous relationship who is making you feel unsafe now?

http://www.nnepqin.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Screening-Tools-Partner-Violence-Screen-PVS.pdf

Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS)

A multiple section assessment tool for sexual and physical violence, including body maps for documentation of injuries.

https://idph.iowa.gov/Portals/1/Files/FamilyHealth/abuse_assessment_tool.pdf

The Crisis Prevention Institute (CPI) [16] encourages you to always be aware of physical signs and injuries that could be related to domestic violence, including but not limited to the following:

- Bruising in the chest and abdomen

- Multiple injuries

- Minor lacerations

- Ruptured eardrums

- Delay in seeking medical attention

- Patterns of repeated injury

- Injuries inconsistent with the presenting complaints

Oftentimes, a domestic violence victim may seek medical attention for issues unrelated to a physical injury, such as:

- A stress-related illness

- Anxiety, panic attacks, stress, and/or depression

- Chronic headaches, asthma, vague aches, and pains

- Abdominal pain, chronic pelvic pain

- Vaginal discharge and other gynecological problems

- Joint pain, muscle pain

- Suicide attempts, psychiatric illness

Other observations that may indicate a suspected domestic violence situation include:

- Appear nervous, ashamed, or evasive.

- Seem uncomfortable or anxious when around their partner.

- Be accompanied by their partner, who controls the conversation.

- Be reluctant to follow advice.

As you continue to assess the patient, encourage them to talk and then listen carefully. Only upon listening will you have a better understanding of the patient’s current state and provide the necessary resources and referrals for them to find safety. Above all else, maintain open lines of communication in a safe, accepting environment and assure the victim that they do not deserve the abuse.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What screening tools are currently available at your facility to assess for possible domestic abuse? Do you feel that they are effective?

- Domestic abuse victims may seek medical attention for issues unrelated to abuse (chronic headache, vague aches, and pain, anxiety, or depression). What further assessments can be done to assess for domestic violence?

Importance of Trauma-Informed Care

While nurses play a critical role in recognizing suspected domestic abuse victims, they often do not feel confident in their role or the screening process itself. This may be due to a lack of communication skills, ongoing training on domestic violence or simple confusion over what victim assistance programs and resources are available [17].

Facility-wide education on domestic violence should be ongoing. Policies and procedures should be on file, and collateral relationships should be in place with the local community and national resources. Finally, nurses should be trained in the delivery of trauma-informed care to ensure the highest quality of interaction with victims of domestic violence, much less all victims of trauma.

Trauma-informed care has been defined as the patient-centered approach that encourages healthcare professionals to provide care that does not retraumatize the patient and the staff [18]. Trauma-informed care ensures that policies and practices in the healthcare setting are not only safe but non-threatening to the physical and mental well-being of those involved. Perceived threats can cause a “flight or fright” mentality that impacts both the ability to administer care and receive immediate care and follow-up recommendations.

The experience of seeking medical care, whether in an emergency department setting or a clinic, can in and of itself being another source of trauma. Trauma-informed care aims at reducing the impact of trauma on both the patient and provider by focusing on various checkpoints overseeing all interactions: safety, trustworthiness, empowerment, and respect.

The following examples are practical tips that encourage trauma-focused care, ensuring the delivery of care in the least threatening manner to a suspected human trafficking victim (as well as each patient you may intersect with).

- Always introduce yourself and your role within the patient’s care with every interaction.

- Use open body language (direct eye contact, avoid standing “over “the patient as it may be perceived as threatening).

- Explain procedures and timelines for results (“wait times”) to give patients a sense of control. Keep them informed of any changes/delays in their care.

- Always ask before you touch a patient. This is a sign of respect and gives the patients a sense of control over their bodies.

- Protect patient privacy. Ask them who they would like present during their care; limit visitors if requested; close room doors (with their permission).

During the interview and intervention process, it is also equally important that some things NOT be said to a suspected victim of domestic violence, such as negating, challenging, or doubting the victim. Examples include:

- Why haven’t you called the police before now?

- Some level of fighting occurs in all relationships.

- Maybe you’re both going through a phase; it will probably stop on its own.

- You wouldn’t stay in this situation if you really care about yourself/ your kids.

- What did you do to make them get so angry?

- Why didn’t you leave the first time you were hurt?

By applying trauma-informed care to all your patients, you lower the risk of perceiving any (nursing and medical) interventions being perceived as a threat. This ensures a higher level of trust and respect, and safety for all patients (and staff) across the care spectrum.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Describe the possible consequences of doubting a victim of domestic violence.

- What can you do as a healthcare professional to ensure all patients are screened for domestic violence?

Legal Issues: Florida Mandatory Reporting Laws

The United States Department of Justice [19], defines domestic violence to include felony or misdemeanor crimes of violence committed by:

- a current of former spouse or intimate partner of the victim,

- by a person with whom the victim shares a child in common,

- by a person cohabitating with or has cohabitated with the victim as a spouse or intimate partner,

- by a person similarly situated to a spouse of the victim under the domestic or family violence laws of the jurisdiction receiving grant monies,

- by any other person against an adult or youth protected from that person’s acts under the jurisdiction’s domestic or family violence laws.

The Florida Department of Children and Families defines domestic violence as patterns of actions or behaviors that adults or adolescents use against their partners or former partners to establish power and control. It can potentially include physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and economic abuse. It may also include threats, isolation, pet abuse, using children, and a variety of other behaviors used to maintain fear, intimidation, and power over one’s partner (19).”

Under Florida law [21], Domestic Battery is classified as a first-degree misdemeanor, with penalties including up to one year in jail or twelve months’ probation and a $1,000 fine. In addition, the accused may face additional penalties of a mandated Batterer Intervention Program.

RAINN (Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network) [22] is the nation’s largest anti-sexual violence organization. Under the “Laws of your state” section, they outline the mandatory reporting laws for Florida.

Mandatory Reporting Requirements on Children

Children are defined as any unmarried person under the age of 18 years who has not been emancipated by court order.

Who is required to report (from a healthcare professional standpoint):

- Physicians

- Osteopaths

- Medical examiners

- Chiropractors

- Nurses

- Hospital personnel

When is a report required:

- When any person knows or has cause to suspect that a child is abused, abandoned, or neglected by a parent, legal custodian, caregiver, or another person responsible for the child’s welfare, or that a child is in need of supervision and care and has no one to provide supervisional care.

- When any person knows or has cause to suspect that a child is abused by an adult other than a parent, legal custodian, or another person responsible for the child’s welfare.

- When any person knows or has cause to suspect that the child is a victim of childhood sexual abuse or the victim of a known or suspected juvenile sexual offender.

Reports can be made to the Department of Children and Family Services’ abuse hotline at (1-800-962-2873)

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What policies and protocols are in place at your facility regarding mandatory reporting?

- Who can initiate a report?

- What departments are notified, at your facility, if a report is made?

Elements of a Safety Plan (Escape Plan)

Abusers may go to extremes to prevent a victim from leaving. This may result in the decision to escape an abusive relationship, one of the most dangerous times for the victim of domestic violence. The creation of a safety plan can assist in enhancing the safety of a victim during all phases of a relationship and during the planning phase of actually leaving the abuser.

Knowledge of the various elements of a safety plan will enable the healthcare professional to initiate dialogue with a victim and guide them in the development of a personalized plan of safety moving forward. Discussion of safety plans/escape plans can be very difficult during the limited interactions of an emergency room or clinic visit; therefore, familiarity with the key elements of a plan will help navigate the victim to the most appropriate resources for their situation.

The following overviews of a safety plan are from Safe Horizon [23] and the National Domestic Violence Hotline [24]. The Safe Horizon is victim assistance nonprofit for victims of violence and abuse in New York City since 1978. The following outline provides a detailed overview of the many aspects to consider when formulating a safety plan. Review the entire plan outlined on their website. Consider creating a template handout for your facility to distribute to domestic violence victims.

A safety plan is an outline that includes ways to remain safe while in a relationship, planning to leave, or after you leave (23). A personalized safety plan assists in coping with emotions, telling friends and family about the abuse, and the steps to be taken in the event of necessary legal action. An effective safety plan should have specific details tailored to your unique situation.

Considerations in creating your safety plan:

- Do you have a trusted confidant – a friend, family member, or neighbor?

- Where are some areas in your neighborhood that you could go to in an emergency?

- Are there phone numbers you need to memorize in the event of an emergency?

- Do you have children that need to be part of your safety plan? Where would your children go if they witnessed violence?

- Do you need a safety plan for work school?

- Where can you safely store your safety plan? Computer? Phone?

Before Leaving

The decision to leave an abusive relationship requires courage and pre-planning. Consider these measures before leaving to reduce the risk of violence (23):

- Record evidence of physical abuse

- Plan with children and identify a safe place where they can go during moments of crisis. Reassure them that their job is to stay safe, not to protect you.

- Call ahead to see what the shelter’s policies are. They can provide information on how they can help and secure a space when it is time to leave.

- Try to set money aside or ask trusted friends or family members to hold money for you.

When Leaving

The following list of items serves as a guide for what to take (23):

Identification

- Driver’s license or state I.D. card, social security card

- Birth certificate and children’s birth certificates

- Money and/or credit cards

- Checking and/or savings account books

Legal papers

- A protective order, if applicable

- Health and life insurance papers

- Legal documents, including divorce and custody papers

- Marriage license

Emergency numbers

- Local domestic violence program or shelter

- Trusted friends and family members

- The Hotline

Other items to keep in mind:

- Medications and refills (if possible)

- Emergency items, like food, bottles of water, and a first aid kit

- Multiple changes of clothes

- Emergency money

- Address book

- Safe cell phone, if possible

After Leaving

The safety plan should always include ways to ensure your continued safety after leaving an abusive relationship. Here are some precautions to consider (23):

- Change locks and phone numbers if possible.

- If possible, change work hours and the typical route.

- Alert school authorities of the situation.

- If a protection order is present, keep a certified copy present at all times, and inform friends, neighbors, and employers that you have a protection order in effect.

- Consider renting a post office box or using a trusted friend’s address for mail (remember that addresses are used for restraining orders and police reports)

- Use different stores and frequent different social spots.

- Alert neighbors and work colleagues about how and when to seek help.

Tell people who take care of children (if you are comfortable doing so) or transport them to/from school and activities.

Again, these suggestions provide an extensive overview of an escape plan. They are meant to assist a victim in the required methodical preplanning of a safety plan that reduces the threat of violence. Not all sections will apply to every victim, but healthcare professionals should be comfortable in discussing any aspects of a safety plan specific to the individual victim.

The Effects of COVID-19 on Domestic Violence

As discussed at the beginning of this educational offering, the COVID-19 pandemic has negatively affected domestic violence incidence. Stay at home /shelter in place orders, job losses, and mounting financial concerns, and lack of available shelters in many areas became the norm. Domestic violence victims have met with further hurdles to their safety and well-being, as they found themselves sheltering in place with their abuser, along with fewer resources available to them in their time of crisis.

Domestic violence hotlines prepared for an increase in calls; many organizations found the opposite was occurring. Calls to hotlines dropped, in some places greater than 50 percent. Victims were not able to safely connect with necessary services [25].

Due to the restrictions of movement (curfews, travel bans, 14-day quarantine advisories), not only is it more difficult to escape, but injury from abuse may go unnoticed by family and friends as face-to-face interactions have been sidelined. In addition to job losses and financial insecurities, this isolation may force a victim to become even more dependent on their abuser [26].

In March 2020, U.S. police departments reported an increase in domestic violence calls as high as 27% after stay-at-home orders were implemented. The number of Google searches for family violence-related help during the outbreak has been substantial. This increase in domestic violence has not only affected the United States. In the United Kingdom, calls to the Domestic Violence Helpline increased by 25% in the first week after implementing lockdown measures. Furthermore, In China, domestic violence has reportedly increased three times in Hubei Province during the lockdown [27]. The importance of ongoing domestic education and awareness cannot be overstated.

In review, healthcare settings are often treating victims of domestic violence. Trauma-informed care that is patient-focused affords both the staff and patient (victim) the best outcome in terms of successfully navigating the challenges of domestic violence and mandatory reporting laws.

Facility-wide protocols should be in place regarding all aspects of patient care for suspected victims of domestic violence: national hotline numbers, community resources, scene safety protocols, and house-wide education. Staff should be regularly in-serviced on interviewing techniques, suspected DV victim indicators, and ongoing community collateral relationships. Improved recognition of these victims and knowledge on how to proceed with specific treatment protocols will lead to a higher level of positive outcomes for domestic violence victims and other forms of abuse.

Time is of the essence when dealing with victims of DV. There may be a small window of opportunity to help these victims when they present to your facility. There may be numerous needs identified quickly (transportation, housing, interpretation services, crisis intervention, case management, safety planning, transitional shelter, and protective orders, to name a few). Staff must feel confident in their abilities to identify possible victims, guide them through the process of seeking help, and advocate for their safety and well-being. Knowledge of their facility protocols and community, state, and national resources will afford them the opportunity to deliver optimal care.

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- Can you give examples of what your facility is doing to address the issue of domestic violence?

- How has COVID-19 affected your facility in terms of the availability of community resources for victims of domestic violence?

- What improvements can be made at your facility regarding domestic violence education and awareness?

Case Study on Domestic Abuse

Mary, 26 years old, presents to the emergency department with complaints of abdominal pain, vague body aches, and a headache. During the triage screening, Mary has minimal eye contact with the nurse and appears inadequately dressed for the cold weather, arriving in only jeans, a t-shirt, gym shoes, and a light sweater. While the nurse helps Mary change into a hospital gown in a private examination room, she notices various bruises on Mary’s lower back, arms, and legs, all varying size and color. Mary states she slipped and fell recently at home. You observe that Mary is now avoiding all eye contact, staring down at the ground. She keeps looking at the door, and wall clock, mumbling, “he can’t know I’m here.”

What are your initial thoughts about Mary’s physical appearance?

What can you do to make Mary feel more relaxed, comfortable, and safe during her emergency room visit?

Mary lives with her boyfriend, Bill. He works part-time; she is currently unemployed. She admits to the occasional use of alcohol and recreational use of marijuana “to help me relax; my anxiety is very bad lately.” She mentions that her anxiety has increased because “Bill’s hours at work have been cut due to COVID-19 and were strapped for money. He is under a lot of pressure”.

On further examination and laboratory testing, including a pelvic examination, it is confirmed that Mary is approximately six weeks pregnant and has a suspected STI. Mary bursts into tears and says, “he is going to kill me. We can’t afford a baby; what am I going to do?!”

What are your concerns about this scenario? How will you address these concerns with your patient, Mary?

Why might healthcare professionals, in general, feel uncomfortable talking with Mary?

What are the top priorities of Mary’s care at this time?

What information would you document in the patient record during this visit?

Mary begins to feel comfortable speaking to you about her situation. She reluctantly tells you that Bill pushed her down the back stairs yesterday after an argument but quickly apologized afterward. On another occasion, Bill “beat me up” when he ran out of beer before payday. She states he has been really angry lately over his hours being cut at work and is looking for another job. “A baby now”, Mary confides, “would be a terrible thing for Bill, but I want it. It’s my first, and I want it. Please help me”. Mary gives consent for you to contact your department social worker for additional guidance but does not want law enforcement notified.

What other key staff members need to be part of the care team for Mary?

What local and national resources can you refer Mary to at this time?

How would your plan of care change if Mary did not give consent for the social worker to be notified?

Mary wants to “go back home” tonight so as not to upset Bill when he returns later this evening. “It will be better this way.” She promises to leave him tomorrow and follow-up with the community referrals you gave her. Knowing that these plans may change, you advise Mary to create a safe escape plan “just in case.”

What items should be part of a safe escape plan?

How safe is it for Mary to return home?

What are your legal obligations to Mary regarding Florida’s mandatory reporting laws?

As you are getting ready to leave at the end of your shift hours later, you see Mary arrive by ambulance. She is visibly injured with a broken nose and bloody lip. EMS staff state the neighbors called 911 when they heard Mary screaming in her apartment next door. No one else was in the apartment when they entered, and Mary will not tell them who injured her. You escort them to a private examination room. Mary sees you and yells, “he’s coming after me. Help me. He is going to kill me.”

What are your top priorities for Mary and the staff at this time?

What other hospital departments need to be notified?

Mary’s boyfriend shows up, intoxicated, at the triage window, demanding to see Mary. He threatens to kick in the door to the main examination room if he cannot see Mary immediately. He is pacing back and forth in the triage area and refuses to sit down.

What additional security measures need to be in place upon the boyfriend’s arrival?

Mary’s boyfriend is removed from the premises by local law enforcement. Mary is given the national hotline number and is contacting the local shelter at this time. Upon discharge, she is escorted by security personnel to the exit and leaves the facility with a shelter representative.

Domestic Violence Resources

Florida Specific Domestic Violence Resources

1. Community Legal Services of Mid- Florida

https://www.clsmf.org/violence-protection/

A full service civil legal aid law firm that promotes equal access to justice, providing professional legal aid on domestic violence to help low-income people protect their health, and their families.

2. Coast to Coast Legal Aid of South Florida

https://www.coasttocoastlegalaid.org/

The Family Law Unit primarily focuses on representing victims of domestic violence in family law matters, such as obtaining an injunction (restraining order), dissolution of marriage cases (divorce), and custody litigation.

3. Domestic Shelters.org

https://www.domesticshelters.org/help/fl.florida

Overview of 58 Florida based organizations offering domestic violence services in 47 different cities.

Florida Department of Children and Families

1. Florida Family Policy Council

https://www.flfamily.org/get-help/domestic-violence

Resources to assist victims (and family members) to find help, safe shelter, legal aid, transitional services, and counseling.

2. Child Protective Services

https://www.myflfamilies.com/service-programs/abuse-hotline/

1-800-962-2873 / TTY: 1-800-955-8771

3. The Florida Abuse Hotline accepts reports 24 hours a day and 7 days a week of known or suspected child abuse, neglect, or abandonment and reports of known or suspected abuse, neglect, or exploitation of a vulnerable adult.

https://reportabuse.dcf.state.fl.us/

5. Domestic Violence Hotline 1-800-500-1119

These services include emergency shelter, counseling, safety planning, case management, child assessments, information, and much more.

These shelters may be viewed on the MyFlFamilies.com website. Healthcare professionals should be familiar with shelters available in their surrounding area.

6. Harbor House of Central Florida

https://www.harborhousefl.com/get-help/safety/ (407) 886-2856

Offering housing placements service, legal aid, safety planning, support groups, and crisis intervention.

7. The 15th Judicial Circuit of Florida Batterers Intervention Program (BIP)

https://www.15thcircuit.com/program-page/bip

The Florida BIP is a 6-month intensive program to address root causes of domestic violence; it is at least 26 weeks of group counseling sessions. A list of statewide providers is available on this site.

8. The Salvation Army

https://salvationarmyflorida.org/domestic-violence-program/

Offering emergency and transitional housing, as well as counseling and rehabilitation services.

National Domestic Violence Resources

1. Amend, Inc.

AMEND is a nonprofit organization working to end domestic violence by providing counseling to men who have been abusive, advocacy and support to their partners and children, and education to the community. Based in Colorado.

2. Emerge

https://www.emergedv.com/ 617-547-9879

Emerge is a Massachusetts Certified Batterer Intervention Program & Training Site, offering abuser education groups and batterer intervention. Based in Massachusetts.

3. National Domestic Violence Hotline

1-800-799-SAFE (7233)

4. Domestic Violence Prevention, Inc

https://www.dvptxk.org/ 903-793-HELP (4357)

501C3 nonprofit offering education, counseling, and support services to domestic violence clients in multiple counties in Texas and Arkansas.

5. National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma and Mental Health

http://www.nationalcenterdvtraumamh.org/resources/national-domestic-violence-organizations/

Offering direct website links to multiple national organizations working with domestic violence cases

6. National Network to End Domestic Violence

Offers a range of programs and initiatives to address the complex causes and far-reaching consequences of domestic violence.

7. New York Model for Batterer Programs

https://www.nymbp.org/ 845-842-9125

Court-ordered program for batterer education, which includes a court-imposed consequence if the offender does not attend. Based in New York.

8. Women’s Law

Providing state-specific legal information and resources for survivors of domestic violence.

References

- National Statistics. (n.d.). National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. Retrieved February 7, 2021, from https://ncadv.org

- Sharma, A., & Borha, S. (2020, July 28). Covid-19 and Domestic Violence: An Indirect Path to Social and Economic Crisis. PubMed Central (PMC). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7386835/

- What is domestic abuse? (n.d.). Https://Www.Un.Org/En/Coronavirus/What-Is-Domestic-Abuse. Retrieved February 8, 2021, from https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/what-is-domestic-abuse

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, October 9). Intimate Partner Violence. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a, March 9). Preventing Teen Dating Violence. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). https://www.cdc.gov/injury/features/dating-violence

- National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (2020). Domestic violence. Retrieved from https://assets.speakcdn.com/assets/2497/domestic_violence-2020080709350855.pdf?1596811079991

- Yousefnia, N., Nekuei, N., & Farajzadegan, Z. (2018, July 10). Injury and Violence. PubMed Central (PMC). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6101232/

- National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (n.d.). Dynamics of Abuse. National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (NCADV). Retrieved February 9, 2021, from https://ncadv.org/dynamics-of-abuse

- Pereira, M., Azeredo, A., Moreira, D., Brandão, I., & Almeida, F. (2020, May). Personality characteristics of victims of intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Science Direct. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1359178919302642

- Axelrod, J. (2016, May 17). Who Are the Victims of Domestic Violence? PsychCentral. https://psychcentral.com/lib/who-are-the-victims-of-domestic-violence#1

- National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (n.d.-b). Signs of Abuse. Retrieved February 9, 2021, from https://ncadv.org/signs-of-abuse

- Domestic Shelters (2014, July 1). Profile of an Abuser. Domestic Shelters. https://www.domesticshelters.org/articles/identifying-abuse/profile-of-an-abuser

- Emergency Nurses Association. (2018). Intimate Partner Violence. Emergency Nurses Association (ENA). https://www.ena.org/docs/default-source/resource-library/practice-resources/position-statements/joint-statements/intimatepartnerviolence.pdf?sfvrsn=4cdd3d4d_8

- Bettencourt, E. (2019, October 4). Domestic Violence and How Nurses Can Help Victims. Diversity Nursing. http://blog.diversitynursing.com/blog/domestic-violence-and-how-nurses-can-help-victims

- Stanford Medicine. (2020). How to Ask. https://domesticabuse.stanford.edu/screening/how.html

- Power, C. (n.d.). Domestic Violence: What Can Nurses Do? Crisis Prevention Institute (CPI). Retrieved February 11, 2021, from https://www.crisisprevention.com/Blog/Domestic-Violence-What-Can-Nurses-Do

- Alshammari, K., McGarry, J., & Higginbottom, G. (2018, July 5). Nurse education and understanding related to domestic violence and abuse against women: An integrative review of the literature. PubMed Central (PMC). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6056448/

- Fleishman, J., Kamsky, H., & Sundborg, S. (2019, May). Trauma-Informed Nursing Practice. The Online Journals of Issues in Nursing (OJIN). https://ojin.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Vol-24-2019/No2-May-2019/Trauma-Informed-Nursing-Practice.html

- The United States Department of Justice. (n.d.). Domestic Violence. U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved February 9, 2021, from https://www.justice.gov/ovw/domestic-violence

- Houseman, B., & Semien, G. (2020, October 17). Florida Domestic Violence. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493194/

- Domestic Battery under Florida Law. (2019). Hussein and Webber, PL. http://www.husseinandwebber.com/crimes/violent-crimes/domestic-violence-battery/

- Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN). (n.d.). The laws in your state: Florida. Retrieved February 14, 2021, from https://apps.rainn.org/policy/?&_ga=2.161880060.1354221772.1613679799-1191886798.1613418373#report-generator

- Safe Horizon. (n.d.). Safety Plan for Domestic Violence Survivors. Retrieved February 9, 2021, from https://www.safehorizon.org/our-services/safety-plan/?gclid=Cj0KCQiApY6BBhCsARIsAOI_GjYsM6rkXLswOpzipsjGADI_JOewgRMdKX39WcUjaB14uFcYieLmM5saAmFREALw_wcB

- National Domestic Violence Hotline. (n.d.). Create a safety plan. Retrieved February 12, 2021, from https://www.thehotline.org/create-a-safety-plan/

- Evans, M. L., Lindauer, M., & Farrell, M. E. (2020). A Pandemic within a Pandemic — Intimate Partner Violence during Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(24), 2302–2304. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2024046

- Wallace, A. (2020, November 4). 11 Things to Know About Domestic Violence During COVID-19 and Beyond. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/things-to-know-about-domestic-violence

- Xue, J., Chen, J., Chen, C., Hu, R., & Zhu, T. (2020). The Hidden Pandemic of Family Violence During COVID-19: Unsupervised Learning of Tweets. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(11), e24361. https://doi.org/10.2196/24361

Florida HIV/AIDS

Introduction

An estimated 1.2 million Americans are living with HIV. As many as 1 in 7 of them do not even know they are infected. The others utilize the healthcare system in a variety of ways, from testing and treatment regimens to hospitalizations for symptoms and opportunistic infections. Healthcare professionals in nearly every setting have the potential to encounter patients with HIV as the disease can affect patients of any age or stage of life (4). Proper understanding of HIV is important in order to provide high-quality and holistic care to these patients. For nurses practicing in the state of Florida, it is also important to understand the laws, statutes, and regulations regarding testing, treatment, reporting, and confidentiality related to HIV and AIDS within the state.

Today, approximately 1.2 million people in the United States are living with HIV, though 1 in 7 people don’t know it. Rates of infection are not equal across demographic groups, and certain factors may increase a person’s risk (7). Patient information to consider when determining someone’s risk includes:

Age

As of 2018, the age group with the highest incidence of new HIV diagnoses is 25-34 years or approximately 36% of new infections. Ages 13-24 are next, though the numbers in this age range are coming down in recent years. From there, the risk seems to decrease as people age, with the 55 years and older group accounting for only around 10% of new diagnoses each year (7).

Race/Ethnicity

Currently, the highest rate of new infections is in African Americans, at approximately 45%. This is incredibly high when you consider that African Americans only make up 13% of the general population. This is followed by Hispanic/Latinos at 22% of new infections and people of multiple races at 19% (6).

Gender

Men are disproportionately affected by HIV, accounting for five times the amount of new infections as females each year. This data refers to the sex of someone at birth. When looking at the transgender population, there is a nearly equal rate of new infections among those who have transitioned male-to-female and female-to-male. Together, transgender people account for 2% of new cases in 2018 (6).

Sexual Orientation

Gay and bisexual men remain the population most at risk of HIV, accounting for around 69% of all new infections in 2018 and 86% of all males diagnosed. Similar racial and ethnic disparities affecting all people with HIV still existed among gay and bisexual men (6).

Location

Different areas of the country are affected at different rates for a variety of factors, including population density, racial distribution, and access to healthcare. The southern states are unmistakably more affected than other regions, with anywhere from 13-45 people per 100,000 having a diagnosis of HIV. California, Nevada, New York, and DC all having similar rates of infection as the southern states and are among the highest in the country. The Midwest and Pacific Northwest are next most affected, with 9-13 people per 100,000. The Northeast and Northwest have the lowest rates nationally at just up to 5 people per 100,000 (6).

Transmission

Perhaps the most elusive part of this virus for many years was how it spreads. We now know that HIV is spread only through certain bodily fluids. An accurate understanding of HIV transmission is important for healthcare professionals to provide proper education to their patients, reduce misconceptions and stigmas, and prevent transmission and protect themselves and other patients (8).

Bodily fluids that can transmit the virus include:

- Blood

- Semen and pre-seminal fluid

- Rectal fluid

- Vaginal fluid

- Breastmilk

- Fluids that may contain blood such as amniotic fluid, pleural fluid, pericardial fluid, and cerebrospinal fluid

If one of these fluids comes in contact with a mucous membrane such as the mouth, vagina, rectum, etc., or damaged tissue such as open wounds, or is directly injected into the bloodstream, then transmission of HIV is possible (8).

Scenarios where transmission is possible include:

- Vaginal or anal sex with someone who has HIV (condoms and appropriate treatment with antivirals reduce this risk)

- Sharing needles or syringes with someone who has HIV

- Mother-to-child transmission during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding (appropriate treatment during pregnancy, c-section delivery, and alternative feeding methods reduce this risk)

- Receiving a transfusion of infected blood or blood products (this is very rare now because of screening processes for blood donations)

- Oral sex with someone who has HIV (though this is very rare)

- A healthcare worker receiving a needle stick with a dirty sharp (risk of transmission is very low in this scenario)

HIV cannot be transmitted via:

- Saliva

- Sputum

- Feces

- Urine

- Vomit

- Sweat

- Mucous

- Kissing

- Sharing food or drink

Reducing Transmission & Infection Control

Patient education about risk and protection against HIV, testing, and what to do if exposed should be standard practice for healthcare professionals in nearly all healthcare settings. Primary care should include risk screenings and patient education routinely to ideally help prevent infections from even occurring or catch those that have occurred early on in the disease process (8).

Strategies include:

- Identifying those most at risk, incredibly gay or bisexual men, minority patients, and those using drugs by injection

- Ensure patients are aware of and have access to protective measures such as condoms and clean needle exchange programs

- Provide routine screening blood work for anyone with risk factors or desiring testing

- Providing access to PrEP medications where indicated (discussed further below)

- Staying up to date on current CDC recommendations and HIV developments

- Maintaining a nonjudgmental demeanor when discussing HIV with patients to welcome open discussion (8)

For patients with a repeated or frequent high risk of HIV exposure, such as those with an HIV+ partner or those routinely using IV drugs, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) may be a good choice to reduce the risk of them contracting the virus. When used correctly, PrEP is 99% effective at preventing infection from high-risk sexual activity and 74% effective at preventing infection from injectable drug use. Depending on the type of exposure risk (anal sex, vaginal sex, needle sharing, etc.), PrEP needs to be taken anywhere from 7-21 days before it reaches its maximum effectiveness. Most insurances, including Medicaid programs, cover PrEP at least in part. There are also federal and state assistance programs available to make PrEP available to as many people who need it as possible. Some side effects are commonly reported, primarily GI symptoms, headaches, and fatigue (8).

For those who have a confirmed diagnosis of HIV/AIDS, the focus should be promoting interventions that will prevent further transmission. One of the biggest determinants for transmission is the infected person’s viral load. Individuals being treated for HIV can have their viral load measured to ensure viral replication is being controlled as intended. A viral load lower than 20-40 copies per milliliter of blood is considered undetectable, meaning the virus is not transmissible to others. Even for those not receiving treatment, there are methods to reduce transmission (8).

Methods of infection control for healthcare professionals include:

- Universal precautions when handling any bodily fluids

- Eyewear when at risk for fluid splashing

- Careful and proper handling of sharps

- Facilities having a standard plan in place for potential exposures

If exposure or needlestick do occur for healthcare professionals, the patient would ideally submit to testing for HIV to determine if the staff member is even at any risk. If the HIV status of the patient is unknown or confirmed to be positive, four weeks of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) may be advised within 72 hours of exposure (8).

Treatment

When HIV is appropriately treated, advancement from HIV to AIDS can be significantly reduced, and quality and longevity of life maximized. In 2018, the CDC estimated around 65% of all US citizens living with HIV were virally suppressed, and 85% of those receiving regular HIV-related care were considered virally suppressed. However, an estimated13% of all HIV cases do not know they are infected. Appropriate medical care and keeping viral loads undetectable is one of the single most effective methods of preventing transmission (4, 5).

For those receiving treatment, a multifaceted and individualized approach can reduce a person’s viral load, reduce the risk of transmission, reduce the likelihood of developing AIDS, and preserve the immune system. Regardless of how early someone receives treatment, there is no cure for HIV, and an infected person will be infected for life. All individuals diagnosed with HIV (even asymptomatic people, infants, and children) should receive antiretroviral therapy or ART as quickly as possible after a diagnosis of HIV is made.

The classes and available meds for ART include (1):

- Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs): these inhibit the transcription of viral RNA to DNA

- Abacavir (Ziagen)

- Emtricitabine (Emtriva)

- Lamivudine (Epivir)

- Tenofovir disoproxil fumerate (Viread)

- Zidovudine (Retrovir)

- Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs): these inhibit the transcription of viral RNA to DNA

- Doravirine (Pifeltro)

- Efavirenz (Sustiva)

- Etravirine (Intelence)

- Nevirapine (Viramune, Viramune XR)

- Rilpivirine (Edurant)

- Protease inhibitors: inhibit the final step of viral budding

- Atazanavir (Reyataz)

- Darunavir (Prezista)

- Fosamprenavir (Lexiva)

- Ritonavir (Norvir)

- Saquinavir (Invirase)

- Tipranavir (Apitvus)

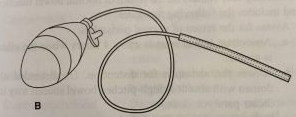

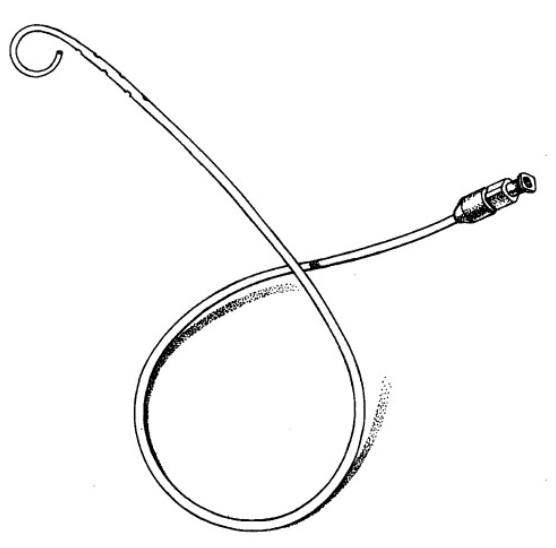

- Fusion inhibitors: prevent the virus from fusing with CD4-T cells

- Enfuvirtide (Fuzeon)

- Integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs): these stop HIV from inserting its DNA into cells

- Dolutegravir (Tivicay)

- Raltegravir (Isentress, Isentress HD)

- Chemokine receptor antagonists (CCR5 antagonists): prevent the virus from binding to CD4-T cells

- Maraviroc (Selzentry)

- Entry inhibitors: prevent the virus from binding to and entering cells

- Ibalizumab-uiyk (Trogarzo) (1)

Florida Law on HIV/AIDS

The Omnibus AIDS Act is based on the premise that illness can be best controlled through public knowledge. If the public is aware of potential illness, and ways to avoid contracting and transmitting illness, that is the best method of prevention and further spread (2). The state of Florida became one of the first states with high rates of HIV infection within their population to enact legislation surrounding the AIDS epidemic. Transmission of HIV, as aforementioned, occurs through direct contact with virus-containing body fluids. Activities by which transmission involves such as sexual activity, needle stick, blood transfusion, or mother to baby, the government cannot regulate. Therefore, the governmental response to a disease epidemic must rely primarily upon the education of the public and its cooperation with their educational efforts and recommendations (2).

Protocols and Procedures for Testing

Healthcare providers performing HIV tests must have advanced procedures in place regarding patient consent, testing samples, and informing patients of their results (2). The informed consent requirement based on the Omnibus act allows the patient to control when and where an HIV test can occur (2).

Health care providers must: (2)

- Disclose that they, as the healthcare provider, are required by law to report the patient’s name to the local county health department if the HIV test results as positive.

- Alert the patient that they may secure an HIV test at a testing site that performs anonymous testing, which the provider is required to make available.

- Explain that the information identifying the patient and the results of the test are confidential and protected.

The rule that parental consent is required before medical diagnosis or treatment of a minor does not apply when sexually transmitted diseases are involved (2). Florida expressly forbids telling parents information relating to the minor’s consultation, examination, or treatment for an STD such as an HIV infection, either directly or indirectly (2). The state of Florida does not require providers to have the patient sign a written document authorizing the test. The health care provider is only responsible for entering a note within the patient’s medical record that the test was explained, and verbal consent was obtained (2).

Exceptions to informed consent requirements by HCP’s (2).

Pregnancy

In 2005, the Florida statute was amended to establish the system of “opt out” testing. In this system, pregnant women are advised that the HCP will conduct an HIV test. However, they have a right of refusal. If an objection is present, it is required in writing to be placed within the patient’s medical record. The rule 64D-2.004, FAC, also requires repeating testing procedures at 28-32 weeks gestation for all STD’s including HIV (2).

Emergencies

A provider can test without consent in a medical emergency only if the provider documents it within the medical record that the results are medically necessary to provide appropriate treatment to the patient if they are unable to consent. This is based on §381.004(3)(h)3, FS.

Therapeutic Privilege

Therapeutic Privilege bypasses informed consent requirements when the provider’s medical record documents that obtaining informed consent would be detrimental to the health of a patient suffering from an acute illness and that the test results are necessary for medical diagnostic purposes to provide appropriate treatment to the patient. This is based on §381.004(3)(h)4, FS.

Sexually Transmissible Diseases

The state law of Florida permit HIV testing for HIV on specific subjects such as convicted prostitutes (§796.08, F.S.), inmates prior to release (§945.355, FS), and cadavers over which a medical examiner has asserted authority(§381.004(3)(h)1.c) without the consent of the subject.

Criminal Acts

Victims of criminal offenses involving transmission of body fluids may require the person convicted or charged of the offenses to be tested for HIV by requests of a court order (§960.003, FS (2).

Organ and Tissue Donations

Provisions permit testing without informed consent with certain blood and tissue donations (§§381.004 (3), 5 and 9, FS.

Research

Established epidemiologic research methods that ensure test subject anonymity is expected from informed consent (§381.004(3)(h)8, FS)

Abandoned Infants

When a physician determines that it is medically indicated that a hospitalized infant have HIV test, but the infant’s parents or legal guardian cannot be located after reasonable attempts, the test may be performed without consent, with the reason being documented in the medical record and the test result being provided to the parent or guardian once they are located (§381.004(3)(h)13, FS).

Significant Exposure

The blood source of significant exposure to medical personnel or to others who render emergency medical assistance may be tested without informed consent (§381.004(3)(h)10-12, FS).

Repeat HIV Testing

Renewed consents agree not required for repeat HIV testing to monitor the clinical progress of a previously diagnosed HIV-positive patient (§§381.004(2)(h)14 and 15, FS.)

Judicial Authority

A court may order an HIV test to be performed without the individual’s consent (§381.004(3)(h)7, FS).

Confidentiality

If an HIV test was performed on an identifiable individual, and any “HIV test result” (negative or positive) is specially protected (§381.004(2)(e), FS). The state of Florida defines the definition of an HIV test and an HIV test result explicitly. An HIV test, as defined by the Florida Statutes, is “a test ordered after July 6, 1988, to determine the presence of the antibody or antigen to human immunodeficiency virus or the presence of human immunodeficiency virus infection (2).” An HIV test result as defined by the Florida statutes is “A laboratory report of a human immunodeficiency virus test result entered into a medical record on or after July 6, 1988, or any report or notation in a medical record of a laboratory report of a human immunodeficiency virus test (2).”

The results are excluded as an acceptable “HIV test result” if a patient reports of their HIV- test status from Department of Health anonymous testing sites, from home access HIV test kids, or from any other sources that do not constitute “HIV test results” unless separately confirmed by the provider through a laboratory report or as a medical record (2)

Any patient disclosures of an HIV test or positive infection to any persons other than health care providers caring for the patient under the provisions of the Omnibus Act also do not fall within the statute’s special confidentiality protections.

Voluntary Partner Notification

The person ordering the HIV test is required to advise their patients with HIV-positive test results of the importance of notifying partners who may have been exposed (2). Practitioners are also advised to tell the patient of the availability of voluntary partner notification services provided by the Department of Health. When notifying partners, county health department staff are required NOT to reveal the original client’s identity. Partner notification makes persons aware of their potential exposure to HIV, providing them with referrals to testing, treatment options, and other services (§381.004(3)(c), FS). Notification services also benefit the community by leading to earlier HIV identification and treatment of previously undiagnosed cases of HIV.

HIV Infection Reporting

Florida was one of the first states with a high incidence of AIDS to authorize regulatory procedures requiring physicians and labs to report HIV-positive test results to local health authorities (§384.25, FS). Per Florida law, practitioners and clinical labs that fail to report HIV0positive test results are subject to a $500 fine along with disciplinary action by their individual licensing boards (§384.25, FS) (2,3).

The Ryan White CARE Act, which was enacted in 1990 and reauthorized in 2009 as the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Treatment Extension Act, provides funding to urban areas, states, and localities to improve the availability of care for low income, uninsured and under-insured AIDS and HIV-infected patients and their families (2).

Florida’s HIV infection reporting requirement increases the funding for persons with the illness and enables the HOH to link them to medical support and services in the early stages of infection.

Under the rules by the DOH of Florida (2,3):

- Practitioners must report to their local county health department within two weeks of the HIV-positive diagnosis of all persons, EXCEPT infants born to HIV-positive women, which must be reported the next business day (Rule 64D-3.029, FAC and Rule 64D-3.030(5), FAC.)

- Clinical laboratories must report to the local health department HIV test results from blood specimens within three days of diagnosis (Rule 64D-3.029, FAC).

References

- Arts, E. J., & Hazuda, D. J. (2012). HIV-1 antiretroviral drug therapy. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine, 2(4), a007161. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a007161

- Hartog, J., & Robinson, G. (2013, August). Florida’s Omnibus Act: A brief legal guide for healthcare professionals. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from http://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/aids/administration/_documents/Omnibus-booklet-update-2013.pdf

- Hartog, J., & Robinson, G. (2013, August). Florida’s Omnibus Act: A brief legal guide for healthcare professionals. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from http://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/aids/administration/_documents/Omnibus-booklet-update-2013.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control. (2016). Today’s HIV/AIDS epidemic. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/todaysepidemic-508.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control. (2020). Evidence of HIV treatment and viral suppression in preventing the sexual transmission of HIV. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/art/cdc-hiv-art-viral-suppression.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control. (2020). HIV. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/whatishiv.html

- HIV.gov. (2020). US statistics. Retrieved from: https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/data-and-trends/statistics

- Nursing Times. (2020). HIV: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and transmission. Retrieved from: https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/immunology/hiv-1-epidemiology-pathophysiology-and-transmission-15-06-2020/

Florida Laws and Regulations

Introduction

The state of Florida has several statutes that govern the practice of nurses. These statues consist of Chapters 456 and 464 located in Title XXXII Regulation of Professions and Occupations. The Florida Administrative Code is where Division 64B9 is located.

Chapter 464, often referred to as the Nurse Practice Act, is separated into two parts. Part I discusses the advanced practiced registered nurse, registered nurse, and licensed practical nurse. The purpose of this statue is to ensure that every nurse practicing in the state of Florida is held to and meets the same minimum standards for safe practice. Because of this, nurses who do not meet the minimum standards or display a harm to society are not allowed to practice nursing in the state of Florida. The Board of Nursing is the governing body for the Nurse Practice Act and deal with matters such as provide licensure, create rules, and manage disciplinary actions. Part II focuses on the certified nursing assistant.

Chapter 456 is a statute that is directed at all health care providers and professions. This statute lists the provisions that Chapter 464 is built on.

Division 64B9 is part of the Florida Administrative Code that provides specific rules that pertain to nurses and how the profession is regulated in terms of eligibility to take the examination of selected practice; set standards for nursing education curriculum and institutions; continuing education requirements; license renewal; rules for impairment of the nurse in the workplace and more.

This course is designed to meet the requirements of Division 64B9-5 as it pertains to two continuing educational hours about Florida’s laws and regulations of the nursing practice.

Definitions

Advanced or specialized nursing practice — completion of post-basic specialized, training, experience, and education that are appropriately performed by an advanced practice registered nurse. The advanced-level nurse can “perform acts of medical diagnosis and treatment, prescription, and operation” under the authorization of a protocol with supervision of a physician (2).

Advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) — any individual that is licensed in this state to practice professional nursing as defined above and holds a license in an advanced nursing practice, including (2):

Certified Nurse Midwives (CNM or nurse midwife)

- Able to perform superficial or minor surgical procedures as defined by a protocol and approved by the employing medical facility or with a backup physician in the case of a home birth/

- Start and perform approved anesthetic procedures.

- Order appropriate medications based on patient and condition.

- Mange care of the normal obstetrics patient and the newborn patient.

Certified Nurse Practitioners (CNP)

- Able to manage certain medical problems guided by facility or supervising provider protocols.

- Manage and monitor patients who have stable, chronic illnesses.

- Start, monitor, and adjust therapies for select, uncomplicated illnesses.

- Order occupational and physical therapy based on patient need.

Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists (CRNA)

- Able to order preanesthetic medications as stated and approved by facility protocols and staff.

- Determine and consult with supervising anesthesiologist about the proper anesthesia for patients based on labs, history, and physical, and patient condition.

- Assist with managing the patient in the post-anesthesia care unit.

Clinical Nurse Specialists (CNS)

- A nurse who is prepared in a CNS-focused program that meets the requirements of a typical APRN program. Additionally, they are trained in the area of expertise as it pertains to the advanced practice of nurses.

Board — the Board of Nursing (2).

Licensed practical nurse (LPN) — any person licensed in this state or holding an active multistate license under s. 464.0095 to practice practical nursing as defined below (2).

Practice of practical nursing — the performance of select actions including the management of certain treatments and medications, while taking care of the ill, injured, or infirm; prevention of illness, promotion of wellness, and health maintenance in others under the direction of a registered nurse, or a licensed provider: physician, osteopathic physician, podiatric physician, or dentist; and the teaching of general health principles and wellness to the public and to students other than nursing students. A practical nurse is responsible and accountable for making decisions that are based upon their educational preparation and experience in the profession (2).

Practice of professional nursing — the performance of actions requiring substantial specialized knowledge, judgment, and nursing skill based on applied principles of physical, psychological, social, and biological sciences which shall include, but are not limited to (2):

- The nursing process consisting of assessment, nursing diagnosis, planning, intervention, and evaluation, of care; teaching and counseling of the ill, injured, or infirm in matters of health; prevention of illness, promotion of wellness, and maintenance of health of others.

- The administration of medications and treatments as prescribed or authorized by a duly licensed practitioner as they are authorized to do so by the laws of this state to prescribe such medications and treatments.

- The management and education of other individuals in the theory and performance of any of the acts described above such as nursing students.

A professional nurse is responsible and accountable for making decisions that are based upon the individual’s educational preparation and experience (2).

Registered nurse (RN) — means any person licensed in this state or holding an active multistate license under s. 464.0095 to practice professional nursing as defined above (2).

Registered nurse first assistant (RNFA) — means a registered nurse who assists in surgery while in the hospital setting under a physician. They help maintain cost-effective and quality surgery for patients in the state of Florida. They must be certified in perioperative nursing via core curriculum approved by the Association of Operating Room Nurses, Inc. (2).

Self-Quiz

Ask Yourself...

- What license do you currently hold?

- Have you held another license in the past?

- What types of other licensed providers do you work with?

Board of Nursing: Members and Headquarters Location

13 members sit on the Board of Nursing in Florida with their headquarters located in Tallahassee. These members are approved by the Governor of the state and consist of a diverse group of individuals. Seven of these members are RNs who have been practicing for a minimum of four years. One of these seven must be an APRN, a nurse educator from an approved program, and a nurse executive. Three of the total membership should be LPNs with a minimum of four years of practice, just as the RNs. The remaining three members are individuals who have no connection to the nursing profession and are not affiliated or contracted with a health care agency, facility, or insurance company. One member must be 60 years or older. All members of the Board must be residents of the state of Florida. Terms last for a total of 4 years, and at the end of each term the Governor can, but does not have to, appoint a successor to the position (2).

The members of the Board have a few duties. Their primary job is to ensure that nurses practicing in the state of Florida are doing so safely. In order to do this, the Board members can create and implement rules or provisions to the Nurse Practice Act. Approve educational programs for institutions wishing to teach nursing. They can take disciplinary action against a nurse for violation of the Nurse Practice Act or other Florida laws. Citations, fines, or disciplinary guidelines can be issued by the Board as well (2).

Licensure by Examination and Endorsement

Initial licensure requires an individual take an examination for their desired profession: NCLEX-RN, NCLEX-LPN, and either the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC) or American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) version for those wishing to become an APRN. In order for the Board of Nursing to approve an individual to sit for their desired examination, a list of requirements must be met in full (4):

- Must correctly complete an application for the desired examination and submit a fee set by the Board.

- Submit to a background check conducted by the Department of Law Enforcement.

- Must be in good physical and mental health and is a recipient of a high school diploma or equivalent.

- Has completed the following requirements:

- Graduate from an approved program on or after July 1, 2009, OR

- Graduate from a prelicensure nursing education program that has been determined to be equivalent to an approved program by the Board before July 1, 2009

- Must have the ability to communicate effectively in the English language as determined by the Department of Health through another examination.

It is important to note that there is a section dedicated to the scenario of it an individual fails the examination or does not take it within six months of graduating.

Any individual that does not pass their examination of choice after three attempts must take a Board-approved remediation course before they are allowed to sit for the examination again. From there, they are able to take the test three more times before remediation is required again. Reexamination must be done within six months of taking the approved remediation course (2).

If an individual does not take their examination within six months of their graduation, the individual must take an exam preparation course approved by the Board. It is to be advised that the individual must pay for the course without the use of federal or state financial aid (2).

Courses successfully completed in a professional nursing education program that are at least equivalent to a practical nursing education program may be used to satisfy the education requirements for licensure as a licensed practical nurse (2).

If a nurse holds licensure in another state or US territory decides to obtain Florida licensure can do so through endorsement. The state of Florida requires those who apply to submit a nonrefundable fee, completed application, and fingerprints for a criminal background check. The Florida Board of Nursing will not issue a license to an individual that is under investigation at the time of applying (2).

Military Spouses

Applying for a license through endorsement is a route that can be used for nurses who are following military spouses on official military orders. Nurses must have actively practiced nursing two of the three years prior to applying for a license. Military spouses also have the option of obtaining a 12-month temporary Florida license if they meet the requirements: holds a valid nursing license in another state, has a negative criminal background check, has not failed their licensure exam, and has not had any disciplinary action taken against them in another state (1).

Licensure by Compact