Course

Kentucky Domestic Violence

Course Highlights

- In this Kentucky Domestic Violence course, you will be able to state the definition of domestic violence and intimate partner violence, as well as understand those at risk for domestic violence.

- You will also be able to recognize the importance of collecting a detailed history and physical assessment and identify processes for assessing abuse and barriers of disclosure.

- You will also be able to discuss statistics and the prevalence of domestic violence and identify notational and state resources for victims of domestic violence.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 3

Course By:

Kayla M. Cavicchio

MSN, RN, CEN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

Domestic violence continues to be a prevalent topic in media and society. While many partake in conversation, there can be a severe lack of knowledge on how impactful domestic violence can be. Healthcare providers are in a prime position to provide assessment, treatment, and resources to victims of any age. Recognizing the various types of abuse, the populations affected, and the appearance of victims can create confidence in the nurse who has hundreds of patient encounters annually.

What is Domestic Violence?

Domestic violence is a pattern of abusive behaviors that is utilized by one individual within the relationship to gain and maintain control and power over the other individual(s) in a relationship. Domestic violence can include but is not limited to any of the following: sexual, physical, economical, psychological/emotional, and technological (16).

For reference, the Kentucky statute defines domestic violence as: “Physical injury, serious physical injury, stalking, sexual assault, strangulation, assault, or the infliction of fear of imminent physical injury, serious physical injury, sexual assault, strangulation, or assault between family members or members of an unmarried couple” (16).

The relationship of those involved is not always romantic in nature, as it can be between parents and children, friends, roommates, family, and other individuals that live together in the same household (16).

In recent years, domestic violence has taken on a new name: intimate partner violence. While intimate partner violence is used for those experiencing abuse in an intimate/romantic relationship, some individuals use the terms interchangeably. It is important to note the definitions of each term to clearly understand that while the two can overlap they are not the same (11).

To provide a clear picture, here is an example of domestic violence and intimate partner violence:

- Example of Domestic Violence: a 20-year-old male named Sam lives with his 21-year-old roommate Danny. Danny has physically abused Sam by hitting, kicking, and slapping him often. Danny and Sam are not in a romantic/intimate relationship, and they share their apartment with one other person who is attending the same university as them.

- Example of intimate partner violence: Shelly is a 27-year-old who is in a relationship with her 35-year-old boyfriend Marcus. Marcus often forces Shelly to perform sexual acts she does not want to do as well as control her through threats and acts of physical harm. Shelly does not live with Marcus, but she often finds him always around.

If Danny and Sam had been in an intimate/romantic relationship, the abuse could have been classified as intimate partner violence or domestic violence. If Shelly had been living with Marcus the term domestic violence could have been used; however, since they are not, the term intimate partner violence is more appropriate.

Domestic violence can also incorporate elder abuse and child abuse if the victim resides in the household (16).

For child abuse, the age range is from newborn to age 17 and encompasses a recent act or a failure to act as a parent or caretaker, that results in serious physical or emotional harm, exploitation, sexual assault/abuse, or death or an act or failure to act that can lead to an imminent risk of severe harm (9). Age-related considerations will be discussed later in this course. With elder abuse, the victim must be 65 years of age or older and can be carried out the same way as domestic violence (53).

As mentioned, domestic violence, intimate partner violence, elder abuse, or child abuse can occur in a variety of ways. While there is no full comprehensive list, there are many behaviors that the abuser may utilize to ensure the compliance of the victim (Table 1).

| Sexual | Physical | Economical | Psychological/ Emotional | Technological |

|

Definition: Coercion or attempt to coerce any type of sexual contact, act, or behavior without the consent of the victim.

|

Definition: Intentional acts that lead to physical injury.

|

Definition: Limiting or controlling an individual’s ability to earn, use, or manage financial resources. | Definition: Threatening fear of harm as well as undercutting an individual’s sense of worth or self-esteem. | Definition: Any act done with the intention to threaten, harass, control, harm, stalk, impersonate, monitor, or exploit another individual that occurs by utilizing technology. |

| Examples: Rape (including marital rape); forcing sexual acts after violence has happened; treating the victim in a sexually demeaning manner; attacking sexual parts of the body. | Examples: Shoving, hitting, biting, slapping, hair pulling, burning; strangulation; forcing the victim to consume alcohol and/or drugs, denying medical care or assistance to the victim. | Examples: Using methods of coercion, manipulation, or fraud to limit an individual’s access to assets, money, credit/financial information; exploiting powers of attorney or guardianship; or neglecting to act in the individual’s best interest. | Examples: intimidation that leads to fear, threats of physical harm to victim, abuser, children, and family; forcing isolation; and destruction of property. Name-calling, constant criticism, damaging relationships with family and/or friends, threatening to take children. | Examples: Invading online spaces such as public and private social media sites; using cameras, computers, phones, and location tracking devices. |

| Sources: (3, 59, 60) | ||||

Case Study:

Nora and Keith were both born overseas with Nora currently living in the United States. Keith lives overseas and has completed tertiary education. English is Nora’s second language, but she does require an interpreter to assist her for anything other than basic communication. Keith works in a well-paid, professional job.

The two initially met through an online dating website and agreed to meet in the United States where Keith came for a vacation. The relationship progressed quicker than Nora expected. She was willing to assist Keith in obtaining a tourist visa for Keith and within a few weeks of the visa going through they got married. During the sixth month of marriage, Nora became pregnant.

Since their marriage, Keith has changed. Nora is not allowed to leave the house without Keith’s knowledge of where she is going, what she is doing, who she is with, and when she will be home. If she is not home on time, Keith becomes angry and yells at her. He tells her “You’re stupid and can’t remember anything!” Demeaning names are often used in the household and Keith once told Nora she’d never be able to hold a job and is useless. He insists he is the only one who does anything around the house while working a full-time job. He makes it hard for her to access an interpreter when they are conducting financial business, insisting that he will “take care of it” and that she “doesn’t need to worry about that.” Once he took her phone because he didn’t think it was a good idea to use when pregnant.

At one of her obstetric appointments, Keith was not present due to being at work, Nora admitted to the nurse that she felt worried for herself and her unborn child. She wonders if she could continue helping Keith become a United States citizen, but she quickly brushes that idea away. “He’s just worried about the baby,” she says. “He’s never hit me, so it’s not abuse.”

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Based on the case study do you think Nora is a victim of domestic violence? If so what type or types of abuse could Nora be experiencing?

- Do you agree with Nora’s assessment that what Keith is doing is not considered abuse?

- What could you say to Nora in response to her statement?

- What would be the best way to explain to Nora what the definitions of abuse are? How would you ensure she receives information in her preferred language?

- Do you think you are obligated to call the police in this particular case?

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Etiology: Domestic violence, including child and elder abuse, and intimate partner violence begins because of the abuser’s desire for domination or control of the victim.

Reasons abusers may have the need to control vary, and while this is not a complete list, it does highlight the many reasons why someone may become an abuser in a relationship (8):

- Individual:

- Jealous

- Young age

- Learned behavior from a home where domestic violence occurred or was viewed as acceptable.

- Lack of nonviolent social problem-solving skills

- Low self-esteem

- Anger management or aggressive behavior especially in youth

- Personality or psychological disorders such as antisocial or borderline personality disorder traits

- Alcohol and/or drug use (those who are impaired have a more challenging time controlling urges)

- Low academic success

- Impulsiveness or poor behavior control

- Depression and suicide attempts

- Support/belief of firm gender roles such as male dominance or hostility toward women

- History of being physically abusive

- Relationship:

- Desire for dominance or control in the relationship or the partner

- Unhealthy family dynamics or relationships

- Financial stress

- Witnessing violence, physical discipline, or poor parenting during childhood

- Association with antisocial or aggressive peers

- Parents with less than a high school degree

- Community:

- High poverty, unemployment, and crime/violence rates

- Limited education and economic opportunities

- Low comradery among the community such as not looking out for each other or intervening during a situation

- Society:

- Traditional gender roles and inequality

- Supporting aggression toward others

- Income inequality

Pathophysiology: Research on domestic violence is not definitive when it comes to the pathological findings in perpetrators, there have been several reoccurring characteristics that are common (8):

- Jealous, possessive, or paranoid

- Controlling every activity such as finances and social events

- Low self-esteem

- High consumption of alcohol and/or drugs

- Emotional dependence is present more often in the abuser but can be present in the victim as well.

Case Study

Dominic started off as a nice guy, that’s how Cara always described him. He was always dotting on her and her younger sister Chloe despite Chloe being nine. Most of Cara’s other boyfriends wouldn’t have found Chloe interesting, nor would they want to date her after they found out Cara was given custody of Chloe since their parents passed away. Dominic had been different, in more ways than one.

After a year of dating, Dominic began pushing boundaries in their relationship. If Cara didn’t want to have sex and Dominic did, she ended up giving in despite not wanting to. They fought more than they ever had and after having one of these fights in front of a few friends, there was talk of breaking up. Dominic didn’t like that and promised to change.

For a while, things were okay. They collaborated with a therapist to help them talk through disagreements and they were able to work together. However, Dominic became jealous of Cara when she got a job promotion and promptly started a fight with her when she went to his home that evening. He had been in the same position at work for years and was taught from a young age that women were expected to stay home and care for the children.

Cara ended up breaking up with Dominic a few days later and moving to a new apartment with Chole when her lease was up for renewal.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What about Dominic’s story would lead you to believe he could be an abuser?

- What other information would you want to know regarding his past history?

- Do you think Cara could have handled the situation differently? If so, what do you think she should have done?

- Would you classify this situation as domestic violence or intimate partner violence? What information made you pick one over the other?

The Cycle of Abuse Model

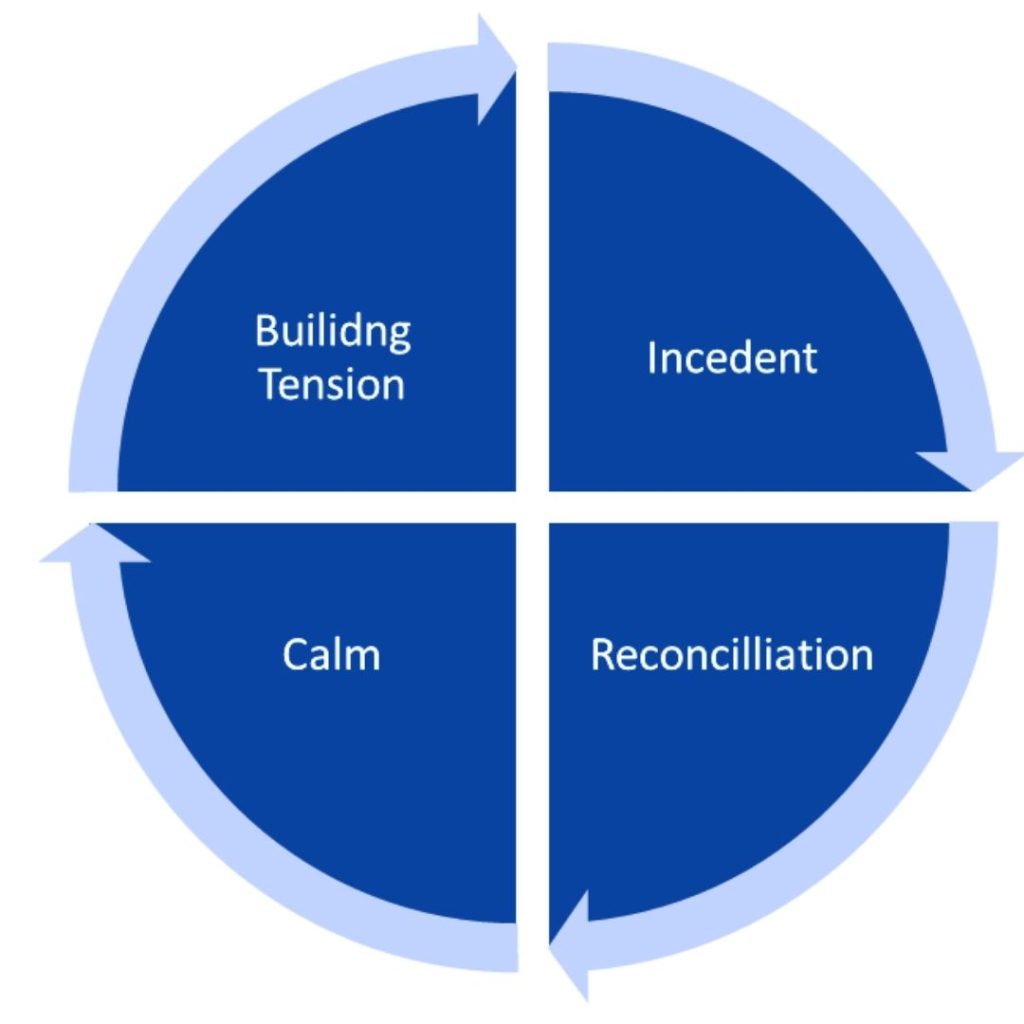

The cycle of abuse is a four-phase wheel that depicts how abuse continues within a relationship (Image 1).

Phase One: Building Tension

In the first stage of the abuse cycle, tension is created and grows. This type of tension can be caused by anything: family, work, financial concerns, catastrophic events, minor to major illnesses, or conflict. These types of stressors are common in everyday life and a majority of individuals are able to cope with them in a healthy manner. Abusers use the stressor(s) as an excuse and as a justification for their actions (19).

Some victims of abuse are likely to try and placate the abuser as a means of avoiding the phase of violence that often follows. They may try to act more submissive or “stay out of the way” or even try and be more helpful to please the abuser. Other victims may do the opposite, provoking the abuser to act and become violent. They are essentially trying to “get it over with” (19).

Phase Two: Incident

The incident phase is where the act of abuse occurs. This can range from physical, psychological/emotional, or verbal abuse and occur in any of the ways listed in Table 1 (please note Table 1 is not a comprehensive list) (19).

As discussed earlier, domestic violence and intimate partner violence are the abuser’s way of gaining and maintaining control and power over the victim. The entire abuse cycle is the abuser’s way of doing that; however, the incident phase is when the abuser is more dangerous and frightening to the victim (19).

Phase Three: Reconciliation

This phase of the cycle is where the abuser may make excuses for the behavior. They may apologize as a way to earn sympathy from the victim: “work has been stressful” or “my mother recently had a stroke, and I don’t know how we will care for her.” Other abusers will blame the victim for their behavior with statements like “don’t make me angry and I won’t have to do this.” Denying the event occurred can be another act the abuser does during the reconciliation phase: “that never happened” (19).

The term gaslighting can be used during the phase and is defined as the attempt of the abuse to create confusion or self-doubt by distorting reality and making the victim question their own intuition, judgment, or memory (40).

Phase Four: Calm

The final stage of the cycle is the calm phase. Often referred to as the “honeymoon phase,” this part of the abuse cycle consists of a period of normality or even better than what life was before the abuse occurred (19).

Love-bombing, defined as an individual manipulating another individual through the act of going above and beyond, may occur as the abuser attempts to “make up for” their actions. This, however, is false as the abuser’s goal is to keep the victim in the relationship and unaware (10).

The cycle remains a cycle because the relationship does not stay in the “calm phase” and instead leads to tension building once again. The cycle will repeat through the relationship with various periods of time between calm and tension building. As the relationship progresses, the time between calm and tension building shortens. This could be attributed to the abuser realizing they can “get away with” their actions since the victim did not leave them or has returned to the relationship/abuser (13).

Breaking the cycle can be extremely difficult for victims. The victim may be ashamed to admit they are a victim of abuse. They may also experience fear due to the violent nature of their abuser; when faced with leaving, the abuser may retaliate and take drastic measures to ensure that the victim does not leave. This can consist of severe physical, mental, or financial abuse. Some acts done by abusers can result in death. Some victims think the abuse is their fault or that they deserve it (13).

Love is a large factor in staying within the cycle. Those who are victims may be or think they are in love with their abuser and that they can “save” the abuser by “fixing them.”

Accepting the abuse as part of an otherwise “good” relationship is another reason why victims may not leave. Other reasons for staying in the relationship can include (19):

- Religion or family pressure

- Lack of financial means

- Lack of knowledge of available services or support network

- Losing children

- Cultural, race, or gender barriers

A Note: Healthcare providers should keep in mind that the abuse cycle model is a simplified version of the complex problem of domestic violence or intimate partner violence. It is important for healthcare providers to not victim blame those in the cycle of abuse; those in the cycle may not see the patterns that those removed from the situation can and may experience denial. Time, distance from the situation, and a different perspective from the situation are often needed for the victim to realize they are or were in the cycle.

Case Study

Nicole presents to her primary care physician’s office for a routine medical exam. Nicole is 20 years old, unemployed, and has a cat at home. Recently, Nicole has decided to move in with her girlfriend Iris but is hesitant to do so. When prompted to discuss it further, Nicole states that her girlfriend “doesn’t understand personal space, but only when she’s at home.”

Iris comes from a conservative family with traditional values. She has not told her family about her relationship with Nicole, presenting Nicole as a “friend that needs a place to stay for a while.” Despite understanding the situation, Nicole says she feels hurt by this since Iris has admitted to telling her family about other girlfriends in the past.

Nicole admits to bringing this up with Iris after they’d been drinking one night. Iris got mad and hit Nicole in the face, possibly breaking her nose. Nicole was too scared to go to the hospital and was admitted Iris said her nose “looked better” and “wasn’t as crooked as before.”

After the fight, Iris seemed like a different person. She showered Nicole and her cat with gifts, making promises about how things would change and that she would introduce Nicole to her family as her girlfriend soon. Things seemed to be okay for a while and Nicole started looking for jobs. She could tell Iris was frustrated with her lack of “trying” to contribute to the household. However, when Nicole was offered a position, Iris yelled and her and guilted her into not accepting the job.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Would you classify the scenario described above as part of the abuse cycle? What stages of the cycle were you able to identify?

- What other information as a provider would you want to know from Nicole?

- What if Iris had been in the room with Nicole, do you think she would have told as much information as she did? What would you have expected to happen instead when asked about domestic violence or intimate partner violence if Iris had been in the room?

- As a healthcare provider, how can you create a safe environment for your patients and help them recognize the abuse cycle?

- What resources could you provide to patients about the abuse cycle to assist them in understanding how it can appear?

Those at Risk

While anyone can be at risk for domestic violence or intimate partner violence, there are groups that are at a higher risk.

Children:

The year 2015 produced nearly four million reports of alleged maltreatment to the child protective agencies in the United States. Of that nearly four million, 683,000 children were officially reported to have been maltreated, abuse being second to neglect. Children from birth to the age of three had the highest rate of being victims with 27.7%. This is important to note because infants and young toddlers rely heavily on parents or caregivers to provide them with food, water, hygiene, interaction, and affection. All of which are vital to proper growth and development. Child victims were slightly more female than male at 50.9% which is consistent with adult statistics as females predominantly being the victim (46).

Data on children exposed to abuse varies as there is no national survey that is dedicated to focusing on children and their exposure to domestic violence. However, there are a few statistics that continue to be cited throughout literature. It is estimated that there is between 3.3 million to 10 million children are exposed to severe parental violence annually in the United States. The research for these statistics varied in collection methods, but one study produced interesting results. Approximately 12.6% of adults who were asked to reflect on their teenage years reported that there had been some type of abuse in the house: 50% reported their father hitting their mother, 19% reported their mother hitting their father, and 31% reported both parents hitting each other (46).

More recent data supports this research. A study conducted by Dong et al. in 2004 discussed adverse childhood experiences with 8,600 adults. Of those that participated 24% stated they had been exposed to child abuse before the age of 18. In this study, the abuser was often the father or stepfather abusing the mother or stepmother. 550 college students were evaluated in another study that showed 41.1% of females and 32.3% of males witnessing abuse as children (46).

While these statistics are staggering, it is important to note that these numbers are only an estimate and can be assumed to be higher or lower based on reporting rates, definitions of domestic violence (physical as well as psychological/emotional, sexual), and time ranges that the surveyor sets (lifetime versus a specific period in time) (46).

Sexual abuse is another concern that regards children and can be a form of domestic violence. Statistics show that one in four girls and one in 13 boys will experience some form of sexual abuse during childhood, and often the perpetrator is someone the child or family knows. More often than not, this type of abuse is carried out by a parent or stepparent, sibling or stepsibling, or other relative who lives in the home. In contrast to teenage or adult victims of sexual assault, child victims are usually brought to a healthcare provider after injury to the genitalia is noted or signs of a sexually transmitted infection are present (2).

While some sexually transmitted infections are transmitted from mother to infant during the delivery phase and can remain present for some time after birth, there is a general rule that any sexually transmitted infection diagnosis after the neonatal phase is considered as evidence of sexual abuse. Care should be taken when collecting specimens and conducting assessments on children to minimize pain and physical and/or psychological trauma (7).

When determining if a patient should be evaluated for sexual assault, healthcare providers should consider if the patient has a recent, evidence of a recent, or healed penetrative injury to the genitals, anus, or oropharynx. A child could present with signs and symptoms such as pain in the genital region, bleeding, tearing, or bruising. If the child or parent/caregiver reports or suspects that the abuse, sexual or physical, was caused by a stranger is another reason to err on the side of caution and consider a sexually transmitted infection screening (45).

If the perpetrator is known to have a high chance of or is infected with a sexually transmitted infection. This can include members of the household that the child lives with. Children with signs and symptoms of sexually transmitted infections such as genital itching and/or odor, vaginal discharge and/or pain, genital legions ulcers, or other urinary symptoms they should be evaluated. If a parent or child requests sexually transmitted infection testing or if the child cannot verbalize the assault that occurred, the provider should consider it (7).

Tests for sexually transmitted infections should have high specificity due to the nature of the situation. Treatment should wait until all samples have been obtained to prevent false results. Healthcare providers should discuss and collaborate with trained professionals on how to ensure testing and treatment is appropriately carried out. Recommendation for Human Papillomavirus vaccinations are encouraged for children with a history of sexual abuse over the age of nine due to the increased risk of unsafe sexual practices in the future. Human immunodeficiency virus testing may be indicated based on the assailant’s history and circumstances of the abuse (7).

Children may also be victims of domestic violence through Munchausen by Proxy where the caregiver or parent exaggerates or fabricates physical or mental health disorders the child has or does not have; Munchausen itself involves the individual, not someone else. The motivation for this is to gain sympathy and attention from family, friends, and others within the community (21).

Young Adults/Adolescents:

Defined as the ages of 13 to 17, adolescent years are more prone to intimate partner violence than domestic violence as opposed to younger children due to the start of dating; however, domestic violence can co-occur with intimate partner violence. Data shows that 1.5 million United States high school students are the victim of physical violence annually. Of the 1.5 million, only 33% discussed abuse with anyone, meaning only 500,000 adolescents are reporting it. When looking into reasons why this may be, as an addition to all the reasons discussed previously, 81% of parents do not believe that teen dating violence is a concern, or they are unaware that it is an issue. Adolescents may not be willing to share with their parents or caregivers due to fear of not being believed or taken seriously (17).

Technology and social media applications can be unmonitored areas of abuse that family and friends are unaware of. Technology abuse was mentioned earlier in this course, but healthcare providers should be aware of how it can appear. Victims of technology abuse may report that someone they are interacting with or dating is forcing them to share passwords or locations, change information on their profiles, and participate in activities online that can be interpreted as humiliating. There may be comments about posts on social media that are seen as jealous; private photos may be leaked, or the abuser may threaten to leak them (48).

Sexual abuse might be harder to diagnose in the adolescent population. This age range is often associated with risky behaviors such as sexual behaviors and using illicit drugs. Healthcare providers should ensure they are screening adolescents thoroughly when they present to any healthcare facility for treatment regarding suspicious injuries or complaints. They may present with serious changes in emotion—anger, low self-esteem, cries for no reason, withdrawal or scared, confusion about sexual orientation—changes in the way they dress, participation in harmful sexual behavior or using alcohol and/or drugs, or avoiding activities they used to enjoy. Physical symptoms may include swelling or redness in the genital area, difficulty walking or sitting, pain or burning when using the restroom, penile or vaginal discharge, or bruising on the buttocks or thighs (45).

Elders:

Elder abuse consists of financial, sexual, emotional, and physical abuse as well as abandonment and neglect. More often than not, elder abuse occurs in the home of the victim which could be classified as domestic violence if they live together. The abuser in the situation is someone the victim has trust with as they are often in charge of many aspects of the victim’s life. The abuse can consist of children, grandchildren, other family members, friends, or other caregivers; studies show that 76.1% of abusers are a member of the victim’s family (30).

It is estimated that four million older Americans are victims of some form of elder abuse annually. Those who require assistance with activities of daily living have an increased risk of emotional abuse or financial exploitation, over 13% of those have suffered emotional abuse since the age of 60. Emotional abuse can be done through the act of demeaning comments about how the victim is “useless” or “helpless” or “weak.” These comments can be seen as embarrassing or humiliating. Since individuals who require assistance to carry out daily tasks may not be able to leave the house often, financial exploitation can be easy for an abuser to carry out. Those who are victims of financial exploitation lost approximately $2.9 billion in the year 2011 (30).

Most sexual abuse cases with elderly patients consist of female victims and male abusers, with only 15.5% of cases being reported to the police. This could be due to fear, cognitive deterioration—50% of older adults diagnosed with dementia are mistreated or abused in some way—or any other reason discussed previously in this course (30).

Women:

On a national level, one in four women have experienced physical violence in their lifetime—often carried out by an intimate partner while one in seven have been injured by an intimate partner. The most abused women fall in the age range of 18 to 24 years old (36). As 18 years old is when most go to college or university or move out of the family home, this age range may not be surprising to some healthcare providers.

For every seven women, one woman states that she was stalked to the point she feared for the safety of herself and/or her family, worrying she or they would be harmed or killed; 19.3 million women have reported being stalked in their lifetime (55). As covered earlier, stalking can be via technology or in-person, depending on the situation and the abuser involved. It is important to remember that intimate partner violence covers past partners or spouses. Data shows that 60.8% of women who have been the victim of stalking report that the stalker was a former or current intimate partner (36).

The number of women who have been a victim of severe physical violence such as strangulation, burning, beating, etc. in their lifetime is one in four. The same number (one in four) consists of those who have experienced severe intimate partner violence. This type of violence contains any of the following: sexual violence and/or intimate partner stalking that can include injury, use of victim services, post-traumatic stress disorder, sexually transmitted infections, or other effects. On average, three women are killed daily as a result of current or previous intimate partners (36).

One in five women have been raped during their lifetime while one in ten women have been raped by an intimate partner, but rape is not the only part of sexual abuse that women can face. In addition to unwanted touching, kissing, and sexual acts, women can also be the victim of reproductive coercion. This type of sexual assault involves the sabotage of contraception medications or forcing a partner to use them, intentionally expose a partner to sexually transmitted infections or human immunodeficiency virus, refusing to practice safe sex, controlling pregnancy through forcing the woman to continue the pregnancy or terminating it through an abortion, refusing sterilization, or controlling the victim’s access to reproductive health care (36).

Data shows that 20% of the women who seek care in family clinics and had a history of abuse reported that they experienced pregnancy coercion and 15% of them had some form of birth control sabotage. Women who were diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection were hesitant to notify their partner of the diagnosis for fear of the abuser denying they were infected or that the woman had been cheating. Those who did discuss their diagnosis reported threats of harm or experienced actual harm as a result (36).

Domestic violence or intimate partner violence with pregnancy occurs in approximately 342,000 women annually in the United States. Women who experience domestic violence or intimate partner violence are more likely to not receive prenatal care, or they are waiting longer to seek out care than what is medically recommended. Depression in the postnatal period for those who are victims of abuse is three times more common than those not experiencing abuse in the home. Women may also experience a higher risk of perinatal death; a three time increase from those not experiencing abuse (55).

It is important for healthcare providers to understand that pregnancy may increase or decrease the amount of abuse experienced by a woman. Each situation varies, but one study showed that abuse peaked during the first trimester and tapered off after that in women who recently experienced abuse. Women who did not have a recent history of abuse did not experience it throughout the pregnancy. This same study noted that psychological and sexual abuse rates were high within the first month postpartum (39).

Domestic violence or intimate partner violence can affect the fetus as well. There is a higher risk of low birth weights, fetal injury, early placenta separation, infection, hemorrhage, and preterm birth (27). After birth, infants can display signs of trauma that include feeding problems, high irritability, sleep disturbances, and delays in development. One good thing is that these can be alleviated with a secure relationship with a safe caregiver (39).

Men:

Men as victims of domestic violence or intimate partner violence is a growing topic in society and data varies. Research states that one in nine men experience severe physical violence at the hands of an intimate partner while one in 25 reports being injured by an intimate partner. Those who have been a victim of severe physical violence such as burning, strangulation, beating, etc. is one in seven men. Of males who experienced any form of domestic violence or intimate partner violence or stalking, 97% reported the abuser was female (6).

Five million males in the United States report being the victims of stalking in their lifetime. It is stated that 43.5% of men who reported stalking stated that a current or former intimate partner was stalking them. Of the data collected, 46% of males were stalked by only female perpetrators, 43% were stalked by male perpetrators only, and 8% were stalked by both male and female perpetrators (6).

Sexual violence data for male victims starts with one in four men having experienced some form of it in their lifetime; one in 14 were forced to penetrate someone—sexually penetrating someone without the other individual’s consent as a result of intoxication, unconsciousness, incapacitation—within their lifetime. Victims of rape, completed or attempted, consisted of one in 38 men with 71% of them experiencing this prior to the age of 25 (6).

Of those that were victims of complete or attempted rape, 87% reported only male perpetrators, 79% reported only female perpetrators, sexual coercion was done by female perpetrators as reported by 82% of victims, unwanted sexual contact was reported at 53%, and done by female perpetrators only, and 48% of non-contact unwanted sexual experiences—such as unsolicited photos—were done by male perpetrators (6).

The data collected and reported is important in healthcare due to the seriousness of the situation. As covered previously in this course, gender roles and society’s expectations of how individuals are expected to act based on their gender can lead to a lack of support or recognition within a certain community. It is the job of the healthcare provider to assess all patients they come in contact with and never make assumptions based on appearances. As this section has shown, males can very well be the victims of domestic violence or intimate partner violence (6).

People of Color:

Rates of domestic violence or intimate partner violence are higher among people of color. In the 2010 National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, those who identified as Native American/Alaska Native and non-Hispanic Black females reported rates of lifetime abuse at 46% and 43.7% respectively. This was in comparison to non-Hispanic White women’s 34.6% and Hispanic women who had a reported percentage of 37.1 (51)

Intimate partner violence was one of the leading causes of death among Black women. Nearly 50% of Indigenous Americans report that they have been “beaten, raped, or stalked by an intimate partner” while over 50% of Asian women have reported physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner during their lifetime (26).

Data on males presented challenging to find. Statistics show that 38.6% of African-American men report domestic violence or intimate partner violence (58).

There are many reasons for the increased statistics among people of color. Discrimination is still prevalent, leading to financial hardships, unemployment, and lack of insurance. This may cause the victim to rely on the abuser for economic support. Oppression may lead people of color to distrust the justice system. They may also be fearful of ending up abused by the system. Stereotypes that depict men and women of color in certain light can lead to conflict between the victim and their depicted “culture.” Women and men may not want to be viewed as weak for being a victim of domestic violence when society depicts them as strong or reinforcing the negative stereotypes about their partners (26).

Religion and spirituality can have certain views on relationships and separation or divorce. Religious leaders may be held in high esteem and be viewed as the only person a couple should go to in order to solve relationship issues (26).

Individuals Classified as Immigrants and Refugees:

Those born outside of the United States have a higher chance of domestic violence or intimate partner violence than other people of color physically born in the United States. One study revealed that 48% of Latinas reported violence from their intimate partners increased after immigration to the United States. Study results ranged from 24% to 60% of women who have immigrated from Asia. Asian immigrant women are at a higher risk for homicide when compared to American-born Asians (47).

Abusers may utilize the legal system to ensure control and hold power over the victim. Legal documents such as passports or identification cards might be taken or destroyed, legal paperwork may not be properly filled out or submitted, or threats of deportation may occur. If the victim has a culture that could be different from the country they are in, there may be some cultural barriers that they are unable to overcome because of the abuser. Victims may not be permitted to learn English (or the primary language of the country they are in) or be prohibited from speaking their native language. The abuser may accuse the victim of abandoning the community, they may use racial slurs against the victim, or they might deny the victim from working or obtaining an education (15).

Domestic violence or intimate partner violence can occur for many reasons within the immigrant or refugee community. Language barriers, difficulty understanding legal rights, and stress in adaptation to a new set of cultural/societal norms can be contributing factors to people of color becoming a victim. Women are at a higher risk due to poverty, disparities in social resources between her and her partner, immigration status, and social isolation (15).

Immigrants or refugees may not be aware that victims of crime, regardless of citizen or immigration status, are entitled to access law enforcement services or the courts. They can receive assistance from government and non-government agencies that can include safety planning, counseling, interpreters, emergency housing, and potentially financial assistance (15).

When services are offered to these individuals they should be focused on the specific and unique needs of the victim. Services are not “one size fits all” and should be tailored to the needs of the victim such as shelters that address specific cultural needs, legal assistance maintaining immigration status or child custody, and access to other victim-specific services (15).

Those that are considered refugees or displaced individuals can experience the same hardships as immigrants. Data about refugees or displaced women who are living in the most forgotten and underfunded locations state that 73% of women reported an increase in domestic violence, a 51% increase in sexual violence, and a 32% growth in early and forced marriage within the first ten months of the COVID-19 pandemic (22).

Members of the LGBTQIA+ Community:

Overall, awareness of domestic violence and intimate partner violence has primarily focused on heterosexual individuals, leaving the members of the LGBTQIA+ community to be underrepresented in the conversations. In recent years, there has been a shift, focusing on all individuals, and data is being collected to provide an accurate picture of how domestic violence and intimate partner violence impacts everyone (35).

Data shows that 43.8% of women who identify as lesbian and 61.1% of women who identify as bisexual have experienced some form of physical violence, rape, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime. In comparison, 35% of heterosexual women reported the same experiences (35).

Discussing gay and bisexual men, 26% and 37.7% respectively, reported physical violence, rape, and/or stalking by an intimate partner as opposed to heterosexual males at 29%. Of those who are in male same-sex relationships, 26% reported calling the police for assistance for near-lethal violence (35).

Less than 5% of members within the LGBTQIA+ community sought out orders of protection after experiencing domestic violence or intimate partner violence. The type of violence experienced by this community ranges from physical violence at 20%, threats and intimidation at 16%, verbal harassment at 15%, and sexual violence at 4%. Of the intimate violence cases reported in 2015, 11% of them involved a weapon (35).

White members of the LGBTQIA+ community are more likely to experience sexual violence while Black/African American members of the LGBTQIA+ community are more likely to experience physical violence at the hands of an intimate partner. Transgender victims are more likely to experience acts of domestic violence or intimate partner violence in public spaces as opposed to those who do not identify as transgender. Those who identify as bisexual have higher risks of sexual abuse, and anyone in the LGBTQIA+ community who is on public assistance is more likely to be a victim of domestic violence or intimate partner violence (35).

Members of the LGBTQIA+ community face unique challenges as it pertains to domestic violence or intimate partner violence. Some members of the community do not share their sexual orientation with others and the threat of “outing” could be used as a method of psychological/emotional abuse. This could also be a barrier to seeking help. Those who have experienced hate crimes or have been a victim of physical or psychological abuse in the past may be less willing to request assistance (35).

Other reasons for not seeking services include fear that bringing attention to the problem will set back equality in the LGBTQIA+ community; domestic violence shelters are sometimes listed as “female or male only” and transgender individuals may not be allowed in; healthcare providers may not be trained in assessing and managing LGBTQIA+ domestic violence or intimate partner violence concerns; fear of or experiencing homophobia/transphobia when reporting; low confidence with the legal system as depicted by media or personal experience; and society believes that domestic violence or intimate partner violence does not occur in the LGBTQIA+ community (35).

Individuals in the Military:

The number of active-duty members of the United States military is over 1.3 million individuals with 16% of that number being women. The spouses of those active-duty members consist of an additional 600,000 members; approximately 25% of them are under the age of 25 years old. Data that was collected showed that in the 2018 fiscal year, there were 16,912 reports of domestic violence or intimate partner violence; almost half of those reports (8,039) did meet the criteria for abuse under definitions created by the Department of Defense. Of those 8,039 cases 73.7% were classified as physical abuse, 22.6% were emotional abuse, 3.6% were sexual abuse, and 0.06% were domestic violence (12).

Comparing data to previous years, events that meet criteria based on the Department of Defense’s definitions have not changed much since the 2009 fiscal year. Reporting has fluctuated due to changes in the number of service members during any given time as well as the addition of sexual abuse reports increasing due to the inclusion of it in the Department of Defense’s definitions for domestic violence or intimate partner violence in the 2009 fiscal year (12).

Nearly 50% of those who reported domestic violence and 66% of those who reported intimate partner violence to the Department of Defense were members of the military when the abuse took place. The 2018 fiscal year resulted in 15 deaths caused by domestic violence or intimate partner violence, 13 being spouses and 2 being intimate partners. Three victims who died as a result of this violence had reported the abuse to the Department of Defense while four of the abusers had previous reports of at least one episode of abuse already on their record. Nine of the abusers were actually civilians acting against military victims (12).

Abusers within military relationships are likely to be underreported, especially if the victim is a civilian, they are not married to the abuser, or they do not live in the military space. Those who are not married to the service member cannot get treatment inside military hospitals or other treatment facilities. Coordination between civilian and military officials for reporting domestic violence or intimate partner violence can be challenging and lead to underreporting (12).

As discussed previously, intimate partner violence can begin in adolescents, leading to the increased risk of future events of violence later on. Those who report sexual violence, domestic violence or intimate partner violence, or stalking do so by the age of 25: 71% of them are females and 58% of them are males. As a note, 23% of women reported their experience occurred by the age of 18. Domestic abuse was prominent in junior enlisted military couples (classified as E-3 and lower), ranging in age from 18 to 24. The 2018 fiscal year showed that 15.1 per 1,000 married couples experienced domestic violence, compared to the overall domestic violence rate of 5 per 1,000 married couples (12).

Data comparing civilian to military populations shows that those within the military sector have lower rates of domestic violence or intimate partner violence overall. Over the lifetime 20% of civilian women and 13.7% of active-duty women report sexual violence; 56.7% of civilian women and 47.2% of active-duty women experience psychological aggression; and 26.9% of civilian women and 21.9% of active-duty women experience severe physical violence. The active-duty women were deployed within three years of the report (12).

Those with Cognitive and/or Physical Disabilities:

Disability is an all-encompassing word to describe individuals with a physical or mental impairment that leads to activity limitation and how they are able to participate in society. This could be termed as participation restrictions. Types of disabilities and how they affect the individual can vary, ranging from mild, to moderate, and severe in terms of how limited they are in terms of participation.

The list below is not all-encompassing but it does highlight some of the more common impairments (5).

- Physical Impairments:

- Visual

- Movement

- Hearing

- Mental Impairments:

- Thinking

- Learning

- Communication

- Social Relationship

- Remembering

These disabilities can present at birth as a result of genetics or the mother’s exposure to something during pregnancy. They can also develop later on in life and present in the form of traumatic brain injuries, illicit substance use, or progressive medical diagnoses (5).

In comparison to women without disabilities, women with disabilities have a 40% greater risk of being victims of violence; these women are at a concerning risk for severe violence. The primary abuser of women with disabilities is their male partners. Sexual abuse is reported to be around 80% of women with disabilities; this is three times more than women without disabilities. A single study reported that 47% of women with disabilities had been sexually abused on more than 10 different occasions (31). Overall, those with disabilities are three times more likely to be sexually abused, and 19% of rapes or sexual abuse were reported to police in comparison to the 36% reported by those without a disability (42).

While those with a disability account for 12% of the population, 26% of the victims of nonfatal violent crimes had a disability. Those with cognitive disabilities had the highest rates of victimization at a rate of 83.3 per 1,000 individuals. Law enforcement responded to 90% of the reports made by victims without disabilities as opposed to the 77% of reports that they responded to as it pertains to victims with disabilities (29). This can lead to mistrust in the justice system that keeps victims from initially reporting the events or seeking assistance in the future. Several studies seem to suggest this view as between 70% to 85% of abuse cases against those with disabilities are not reported. Another study noted that only 5% of crimes committed against those with disabilities were prosecuted; 70% of crimes committed against individuals without disabilities were prosecuted (29).

Those with disabilities face challenges when it comes to leaving domestic violence or intimate partner violence situations. Those providing shelter services may not be trained in disability awareness, studies report approximately 35% have this type of training. Sixteen percent of shelters have an individual dedicated to providing services to women with disabilities. Some individuals may see violence as a way to manage those with disabilities and blame the victim for the abuse, justifying the abuse (42).

Individuals with Mental Illness:

Similar to those diagnosed with disabilities, those who have a severe mental illness—a psychotic disorder such a schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, depressive disorder with psychotic symptoms, or bipolar; or being under the case of secondary mental health services—are more likely to be victims of domestic violence or intimate partner violence. Data is limited, but there is some information regarding domestic violence and sexual abuse. A range of 15% to 22% of women diagnosed with a severe mental illness reported recent domestic violence while men had a range of 4% to 10%. Another study produced similar results: 27% for women and 13% for men. Regarding sexual abuse, women had a 9.9% prevalence in the first study and a 10% in the second. Sexual abuse in men was only reported in the first study with a value of 3.1%. One interesting data point is that sexual abuse in adulthood leads to a 53% increase in suicide attempts among women (25).

Studies also showed that those at the highest risk for physical violence were young males with severe mental illness. As they get older, become employed, and live independently or have a family with responsibilities the risk decreases. Some theorize that not having societal roles for those with severe mental illness can cause them to become victims of domestic violence or intimate partner violence as a method to provide for themselves (25).

As highlighted in other groups, those with mental illness can have a difficult time reporting and leaving an abusive or violent situation. As is with those with disabilities, a diagnosis of a severe mental illness may be seen as less credible when giving reports to law enforcement. Others may accuse the victim of being the abuser due to their diagnosis—media often portrays those with mental illness as dangerous, violent individuals because of stigma. Feelings of hopelessness, low self-esteem, increased symptoms of the mental illness can all be causes of stigma and domestic violence or intimate partner violence (25).

Substance use disorders are prominent in those diagnosed with mental illness. More than one in four individuals with a serious mental illness—depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and personality disorders—also have a substance use disorder. As discussed earlier in this course, substance use can increase an individual’s susceptibility to becoming an abuser, as well as making an individual a victim due to impairment (52).

Individuals Without a Home (Homeless):

For women and children, domestic violence or intimate partner violence is a major cause of homelessness in many communities. It is reported that between 22% to 57% of women who were experiencing homelessness directly attributed domestic violence as the cause for their homelessness. Thirty-eight percent of all domestic violence victims will become homeless at some point; victims may often experience multiple periods of homelessness due to them leaving and returning to the abuser several times before finally escaping the abuser for good. Of women experiencing homelessness, 90% report that they have been sexually abused or have been severely physically abused in their lifetime (37).

The major concern for those experiencing homelessness is safety rating at 85% while finding affordable housing is the second concern rating at 80%. An average stay in an emergency shelter is 60 days, but it takes approximately six to 10 months to secure affordable housing. Only 30 affordable rental units are available for every 100 extremely low income, meaning shelter stays are longer and other victims may be turned away due to a lack of space. These victims who cannot gain access to a shelter may return to their abuser to avoid living on the streets. The 2010 fiscal year revealed that 172,000 requests for shelter were unable to be met due to max capacity (37).

Victims might be evicted or denied housing due to records of domestic violence, regardless of the individual being the victim. Some landlords may not want to risk having violence taken upon them, their families, or their properties by providing housing to the victim. Other landlords have a “zero tolerance” rule when it comes to crime, and they will evict those involved in the crime of violence if it occurs. A Michigan study revealed that women who were victims of domestic violence or intimate partner violence were more likely to be evicted than other women. This can lead to victims failing to report their situation to law enforcement for fear of eviction. A study showed that 65% of test applicants—those seeking housing on behalf of a victim of domestic violence or intimate partner violence—were denied housing or were offered lease terms and conditions that were highly unfavorable in comparison to non-victim applicants (1).

Low-Income:

Individuals who rely on others for financial stability are at a higher risk for domestic violence or intimate partner violence. The lack of financial stability limits the victim’s choice and the ability to escape a violent situation or relationship (49). Women with an income of less than $75,000 are seven times more likely to experience domestic violence than women who have an income over $75,000. Hosing and the neighborhoods that individuals live in can be a contributing factor to domestic violence or intimate partner violence. Women who rent housing can experience intimate partner violence at a rate of three times the amount than women who own their own home. Interestingly, women living in poor neighborhoods and having financial hardship are twice as likely to be victims of domestic violence or intimate partner violence as opposed to women who live in affluent neighborhoods but still have financial hardship (28).

Data suggests that domestic violence or intimate partner violence and finances are related: loss of employment or income can lead to increased stress, both of which have been identified as causes of domestic violence. Difficulty maintaining work can be a contributing factor as well, or relying on part-time, low-paying jobs—as over 70% of low-income parents do now have a high school degree—adds to stress and income instability (28).

Domestic violence or intimate partner violence situations may not lead to unemployment; however, it can be a significant barrier. Physical abuse can lead to missed workdays due to injury, psychological or emotional abuse can lead to poor work performance or severe anxiety, and technology abuse can affect communication with coworkers or management. This creates a cycle that is hard to break; victims may lose jobs due to the increased number of barriers preventing them from working. This can force them to rely on welfare or other assistance programs or their abuser (28).

Individuals Living in Rural Communities:

According to the United States Department of Agriculture the definition of a rural community that has a population density of less than 500 individuals per square mile in open countryside and places with a population of less than 2,500 individuals (54). These locations are significant distances from urban areas and can be an unanticipated place where domestic violence or intimate partner violence can occur (44).

One study evaluated the number of reports of intimate partner violence against women in both small rural and isolated areas—22% and 17.9% respectively—in comparison to women who lived in urban areas at 15.5%. Higher cases of physical abuse were reported among women living in rural settings. This study also evaluated the distance from the rural areas and the closest intimate partner violence program(s) which reported it was three times greater than in urban areas. These services served more counties and limited on-site services or shelters. At least 25% of women in rural or isolated areas live over 40 miles from the nearest program. Less than 1% of women in urban areas are over 40 miles from a domestic violence or intimate partner violence program (44).

As reflected on in this section, many of the individuals listed considered high-risk overlap in categories. Victims are more than male or female, adult, or child, hetero or homosexual. They are more than an individual with or without a disability or mental illness. They are those with and without financial stability. They live in a variety of neighborhoods, cities, and states. It is important that healthcare providers be aware that anyone can be a victim of domestic violence or intimate partner violence—regardless of how minor or severe the abuse is—and assumptions and judgments should be disregarded. Providers should be prepared to assess all patients that come in contact with and be ready to provide assistance and/or resources based on the patient’s needs and wants (44).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Out of all the listed individuals at risk, which one surprised you the most? Why did it surprise you?

- Based on the data provided, do you think what is reported is accurate, higher, or lower in terms of domestic violence cases?

- In your area of work what populations at risk do you encounter more?

- What at risk population do you think faces the most challenges when being a victim of domestic violence? Why do you think that?

Assessing for Domestic Violence

Healthcare organizations have different ways of assessing for domestic violence or intimate partner violence and it is important that providers are aware of their facility’s specific procedures. If no specific screening tool is utilized, healthcare providers may make the decision to implement one of many available (50).

Written questions can be one method of assessment that can be utilized in the waiting room setting and save time on the provider’s end; however, it is important to follow up with the patient regardless of the answer. Many victims will check “no” or be forced to check “no” by the abuser. The healthcare provider should make a verbal statement addressing the “no” and seek reassurance with the answer. A clear statement that could be used is as follows: “I see that you selected “no” to the question regarding domestic violence or intimate partner violence. I want to ensure you do not have any questions about this issue.” If the patient once again answers “no” the provider can reassure that if that were to change, during the visit or in the future, the provider and facility is a safe place to discuss the situation and receive help (50).

The provider should be asking this question in private with the patient as the abuser may be the one who is present with the patient. Finding a way to get the abuser to step out of the room can be challenging. Implementing organizational policies that require providers to have a set time when they discuss healthcare concerns with the patients can be a way to mitigate this, but it is not guaranteed (50).

It is recommended that written assessment forms are kept and signed by the healthcare provider, incorporated into the patient’s permanent medical record, and a provider note added that domestic violence or intimate partner violence was verbally discussed with the patient to ensure that a “yes” is not overlooked (50).

Oral questions are the second method for assessing domestic violence or intimate partner violence. This method does take more time, but sometimes this process can allow patients and providers to ease into the topic.

Providers can start with broad questions such as (50):

- “How are things going at home/work/school?”

- “What is the stress level like?”

- “How are you feeling about your relationships? How is your partner treating you? Are there any problems?”

Patients may wonder why their healthcare provider is asking these questions. They may feel like these are invasive or wonder why it is important to their appointment.

If these concerns are brought up, providers can use that opportunity to shed light on how common domestic violence or intimate partner violence is (50).

- “Since violence is very common in society and can effect health, I ask all of my patients about this.”

- “Many of my patients are experiencing abusive relationships. Some of them may be too scared to bring up the topic themselves, so I have started asking about it to every patient I interact with.”

The other method is to ask direct questions about domestic violence or intimate partner violence.

One set of direct questions is the SAFE Questions adapted from Ashur M. (50):

Stress/Safety

- What stresses do you experience in your relationships?

- Do you feel safe in your relationship?

Afraid/Abused

- 3) People in relationships sometimes fight. What happens when you and your partner disagree?

- Have there been situations in your relationship where you have felt afraid?

- Have you been physically hurt or threatened by your partner?

- Has your partner forced you to engage in sexual activities you didn’t want?

Friends/Family

- Are your friends and family aware of what is going on?

Emergency

- Do you have a safe place to go in an emergency?

Other direct questions can be created based on policy, situation, patient, or age level. Below is a list of questions that can be utilized with young adult and adult patients (50):

- Are you afraid of your partner? Do you feel you are in danger?

- Do you feel safe at home?

- All couples fight, what are fights like at home? Do these fights become physical?

- You have mentioned that your partner has a problem with drinking/drugs/temper/managing stress. When that happens, does your partner ever hurt you?

- Since we last saw each other have you been hit/kicked/punched/etc. or scared?

- Is there anyone in the home that has tried or successfully hit/kicked/etc. or injured you since I last saw you?

- What kind of experiences, if any, have you experienced in your lifetime?

- Do you ever feel controlled or isolated as a result of your partner? This can be in your work life, finances, or relationships.

- Does your partner try to control you through threats of hurting you or your family?

- Has anyone you live with threatened to hurt you or your family?

- Have you ever been slapped, shoved, or pushed by your partner or someone you live with?

- Have you ever been kicked, hurt, or threatened by your partner or someone you live with?

- Have you ever been touched in a way that made you feel uncomfortable?

- Have you ever been made to participate in something sexual despite not wanting to? Regardless of if you said “no” or not.

- Has your partner refused to practice safe sex when you requested it?

- Have you been with your partner and had an episode or episodes of blacking out or not remembering what happened?

- Are you afraid to go home? If so, is there somewhere safe you can go?

- Do you have a safe person you can rely on?

- Have you ever contacted a crisis hotline in the past?

- If so, do you have a contact person there?

- If not, why not?

- Do you know the local and national crisis center hotline numbers?

- Do you know the numbers of a few emergency shelters?

There are many other tools providers can use to assess for aspects of domestic violence or intimate partner violence. One is titled the Danger Assessment and is separated into two parts. The first part is a calendar for victims to document the frequency and severity of the abuse. This can be useful for victims who may be in denial or are trying to minimize the actions of the abuser. The second part of the tool is a set of 20 yes/no questions that are scored to determine the risk for intimate partner homicide (18).

The MOSAIC questions assess how the victim’s situation is similar to other situations that escalated in severity. This method does require a confidential account, but once an account is made and the questions have been answered, a report is created rating the situation on a scale of one to 10. This tool has been utilized by the police employed in determining threats against members of the United States Supreme Court, Congress, and House of Representatives (18).

For children, the Adverse Childhood Experiences quiz allows the individual proving the quiz to score the various types of hallmark signs of abuse, neglect, and rough childhood. The higher the score on the test, the greater the risk was for that child to develop negative outcomes as it pertains to behavior, health, and opportunities later in life (18).

Since stalking is a major topic when it comes to domestic violence the Stalking and Harassment Assessment and Riks Profile is an option for those who are worried they may be a victim of stalking. This test is similar to the MOSAIC in that it requires a confidential account to be made and requires those to answer some questions via an assessment. This assessment takes approximately 15 minutes to complete, and results are generated shortly after, summarizing the situation, and providing the victim with suggestions on how to improve their safety. This assessment is consistent with legal definitions of stalking and was developed with attorneys, law enforcement, victim advocates, prosecutors, and prominent organizations like the Stalking Resource Center (18).

The last tool to be discussed is the Ontario Domestic Assault Risk Assessment. This assessment is done on the abuser, comparing them to other perpetrators. This makes a determination of how likely the abuser is to assault the victim again. There are 13 items on this assessment, and they have a score between zero and one. The result is the total score of all questions, making a maximum number of 13, which is converted into a percentage that estimates the likelihood of abusing the victim again (18).

It is important for healthcare providers to approach this subject after assessing the situation to determine the best way to do so. Trust is very fragile, and it may take several attempts for a victim to feel comfortable enough to speak on the subject. Some may never do so, but asking at every visit or interaction can let the victim know help is available, they are not alone, and they are cared for.

Barriers for Disclosure:

While victims of domestic violence or intimate partner violence can present to any healthcare office or facility, many of them end up in the nearest emergency department. Regardless of where the healthcare provider encounters the victim, they need to be aware of how to assess for domestic violence or intimate partner violence (20).

One major part of the assessment process is the barriers to disclosure. Many barriers exist that healthcare providers have identified, including time constraints. This is something that many healthcare providers can vocalize; limited time leads to rushing through questions and treatments. Lack of training can consist of a lack of knowledge about community services, including 24-hour services; lack of confidence; and concern on how to respond if the patient discloses domestic violence or intimate partner violence. Providers may be worried about offending the patient or have personal discomfort in discussing these topics with individuals (20).

Providers can overcome these barriers through a variety of ways. Time management can assist healthcare providers by adding extra time to each appointment or incorporating the questions while performing other parts of the patient assessment. Lack of knowledge of community resources gives healthcare providers a way to investigate the specific global and community resources to ensure that the patient has a plethora of material they can utilize when they choose to (20).

If worry of offending patients is a barrier to asking patients about domestic violence or intimate partner violence healthcare providers can easily explain that it is best practice, hospital or organizational policy, or the legal obligation of the provider to ask all patients questions regarding domestic violence. Many organizations do have policies that require providers to ask these questions during every visit; note, ensure that your organization’s policies and procedures are properly followed. By explaining that this is a question that everyone is asked, patients may not be offended (20).

Discomfort may lead healthcare providers to avoid the question completely or rush over it in hopes of not having to deal with it. Unfortunately, sensitive topics can lead to discomfort during discussion, but it is important to remember that someone’s life might be in danger, and asking that single question can save a life (20).

Some patients do not leave their abuser despite the resources healthcare providers give them as covered earlier in this course. Regardless of how many times a patient presents to a hospital or doctor’s office, the healthcare provider is responsible for asking, offering resources and support, and providing treatment to the patient. In time the patient may be able to leave the abuser, and trust in a healthcare provider can be pivotal in that moment (20).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What is your organization’s policy regarding domestic violence or intimate partner violence screenings or tools?

- Depending on what you are expected to use, do you feel like this tool is effective? Why do you feel this way?

- Is there a tool that you have seen work particularly well?

- From the list of tools provided above which would you think would work best in your area of practice? Why do you think it would be effective?

- Would you be willing to advocate for the use of that tool in your area of practice?

The History Assessment

Commonly known as a “history and physical,” this is the part of the assessment that delves into the patient’s full medical history and where a physical assessment from head to toe is conducted. Depending on the location of the exam—a doctor’s office versus an emergency department—the collection of this data may vary. A primary care provider’s examination greatly contrasts with an exam performed in the emergency department. Regardless, attention to detail can reveal concerning or conflicting information (41).

A patient’s medical history consists of any and all medical conditions the patient has been diagnosed with, past and present. Treatment for these diagnoses is collected with additional information gathered to determine if there are any side effects or adverse reactions to any treatments. Determining if the patient smokes, drinks, takes any illicit drugs, or uses other tobacco products is the goal of obtaining a social history from the patient. The social history assessment also includes asking about spirituality, sexual activity/habits, occupation, relationship status, and hobbies (41).

Family history is often collected with the medical history to assess the patient for genetic predisposition to certain medical conditions. The surgical history is a record of all elective and emergent surgeries done in the patient’s lifetime. This can include any anesthesia reactions or complications that happened as a result of the surgery. The provider also assesses for allergies and any medications the patients take, both prescribed and over-the-counter (41).

Pediatric considers consist of immunization status and developmental milestones. Parents of infants should be asked about pregnancy challenges or diagnoses such as pre-eclampsia, delivery, prematurity, and postpartum complications. For those of childbearing age, or if menstruation is suspected, asking young adult and adult females about their last menstrual period and the possibility of pregnancy is important (41).

When assessing a victim of domestic violence, collecting a history and physical can produce some challenges. The abuser may present with the patient, dominating the conversation or answering the questions for the patient. They may act like a dotting partner or parent or family member, doing everything they can to be the “perfect” support person for the patient. They may point blame at the patient in a causal manner. “She’s just clumsy” or “he’s such an adventurous toddler; he climbs on everything.” Those phrases may prove to be useful when comparing it to the information gathered from the physical assessment (41).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you encountered a time when you wanted to get the victim alone and could not do so? What did you do in that situation?

- What are some other methods to ensure that the victim is given some time alone with a healthcare provider?

- What other barriers could cause providers to obtain an incomplete history from a victim of domestic violence or intimate partner violence?

- How could the age of the victim present challenges when collecting a medical history?

- How else can providers collect data about victims who may have challenges providing a history by themselves (diagnoses, etc.) to determine if there is reasonable cause to suspect abuse?

The Physical Assessment

Depending on what a patient’s chief complaint is upon presentation to the provider’s office or hospital, some type of physical examination is done. This consists of inspecting, palpating, percussing, and auscultating areas of the body. Some exams are more thorough than others depending on location. An emergency room provider is not going to perform an in-depth head-to-toe assessment on every patient. Instead, they assess the area of complaint and determine a diagnosis or other tests that need to be done. Family providers are more invested in the patient as a whole as they manage the patient’s chronic medical conditions as well as collaborate with specialists to ensure the patient is receiving the best treatments (61).

Below is a table of each body system and how a perfect patient—no medical conditions or diagnoses—would appear versus any signs and symptoms that could indicate a patient is a victim of domestic violence. It is vital to remember that many medical conditions can look like domestic violence: those with clotting disorders are more prone to bruising, so multiple bruises in various stages of healing could be attributed to the medical condition. This is why it is important for healthcare providers to collect a comprehensive medical history as well as a detailed description of why they are seeking help. Some injuries are caused in particular ways that do not match the story being told (61).

| System | Typical Assessment | Potential Domestic Violence |

| Integumentary System |

|

|

| Head, Neck, Face, Eyes, Ears |

|

|

| Mouth, Throat, Nose |

|

|

| Thoracic |

|

|

| Cardiac |

|

|

| Abdominal |

|

|

| Genitalia |

|

|

| Musculoskeletal |

|

|

| Neurologic |

|

|

| Psychosocial |

|

|

| Sources: (27, 41, 45, 59) | ||

The list provided is by no means complete. Healthcare providers may see patients who are coming in for a routine physician appointment, or those patients may be the victims of severe trauma and are fighting for their lives. The case study below depicts one such instance.

Case Study: